User login

Contact Allergy to Topical Medicaments, Part 2: Steroids, Immunomodulators, and Anesthetics, Oh My!

In the first part of this 2-part series (Cutis. 2021;108:271-275), we discussed topical medicament allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) from acne and rosacea medications, antimicrobials, antihistamines, and topical pain preparations. In part 2 of this series, we focus on topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anesthetics.

Corticosteroids

Given their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, topical corticosteroids are utilized for the treatment of contact dermatitis and yet also are frequent culprits of ACD. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) demonstrated a 4% frequency of positive patch tests to at least one corticosteroid from 2007 to 2014; the relevant allergens were tixocortol pivalate (TP)(2.3%), budesonide (0.9%), hydrocortisone-17-butyrate (0.4%), clobetasol-17-propionate (0.3%), and desoximetasone (0.2%).1 Corticosteroid contact allergy can be difficult to recognize and may present as a flare of the underlying condition being treated. Clinically, these rashes may demonstrate an edge effect, characterized by pronounced dermatitis adjacent to and surrounding the treatment area due to concentrated anti-inflammatory effects in the center.

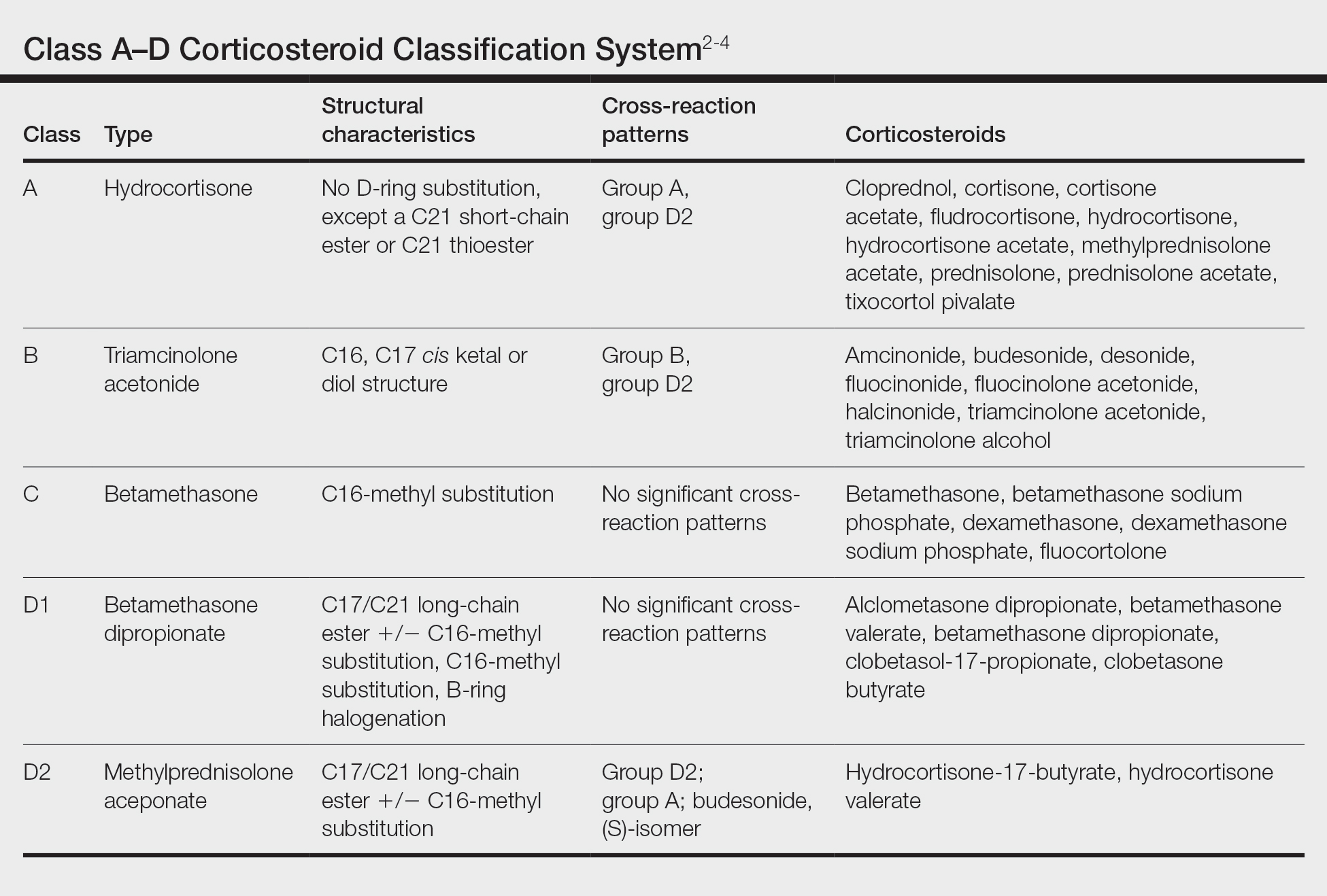

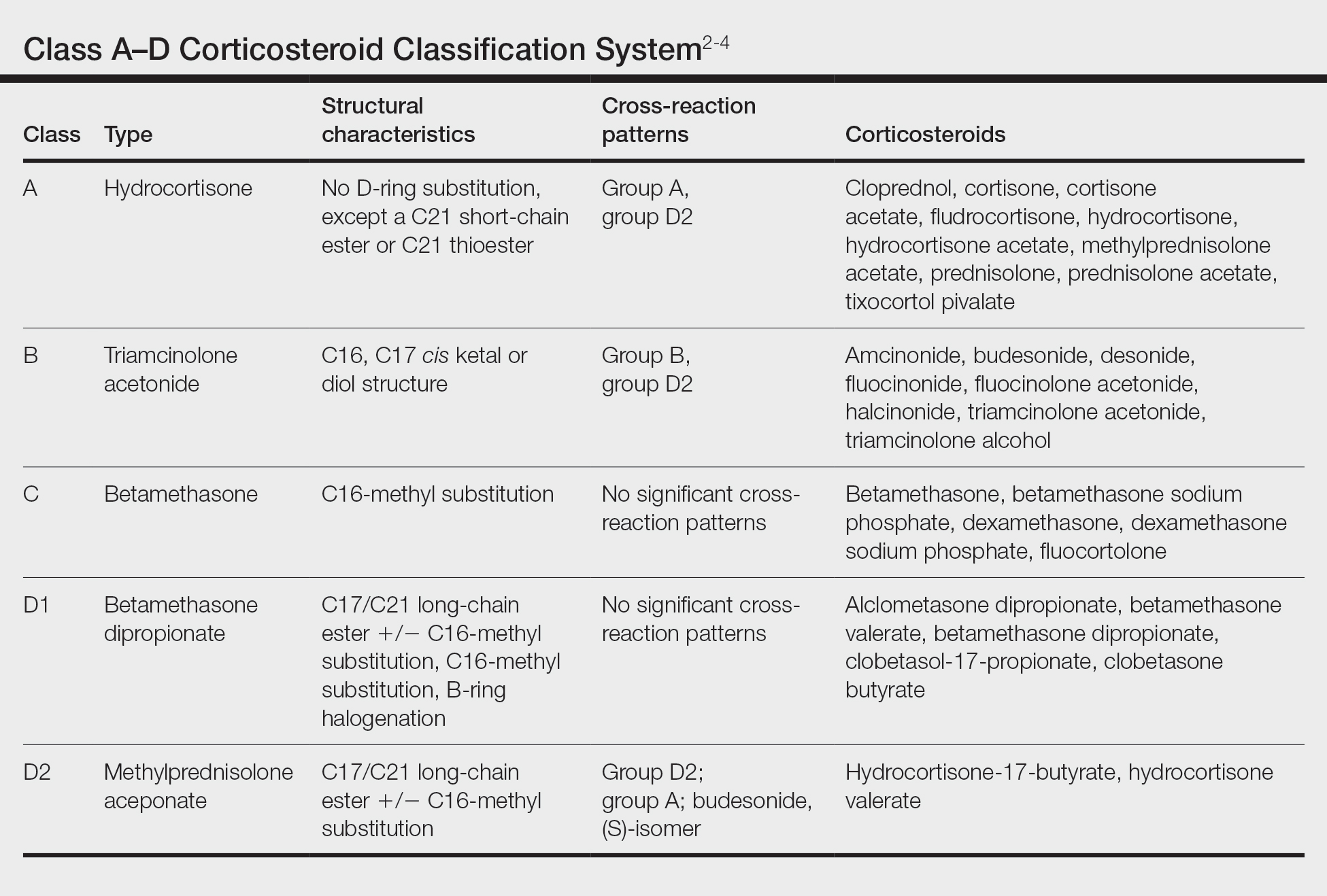

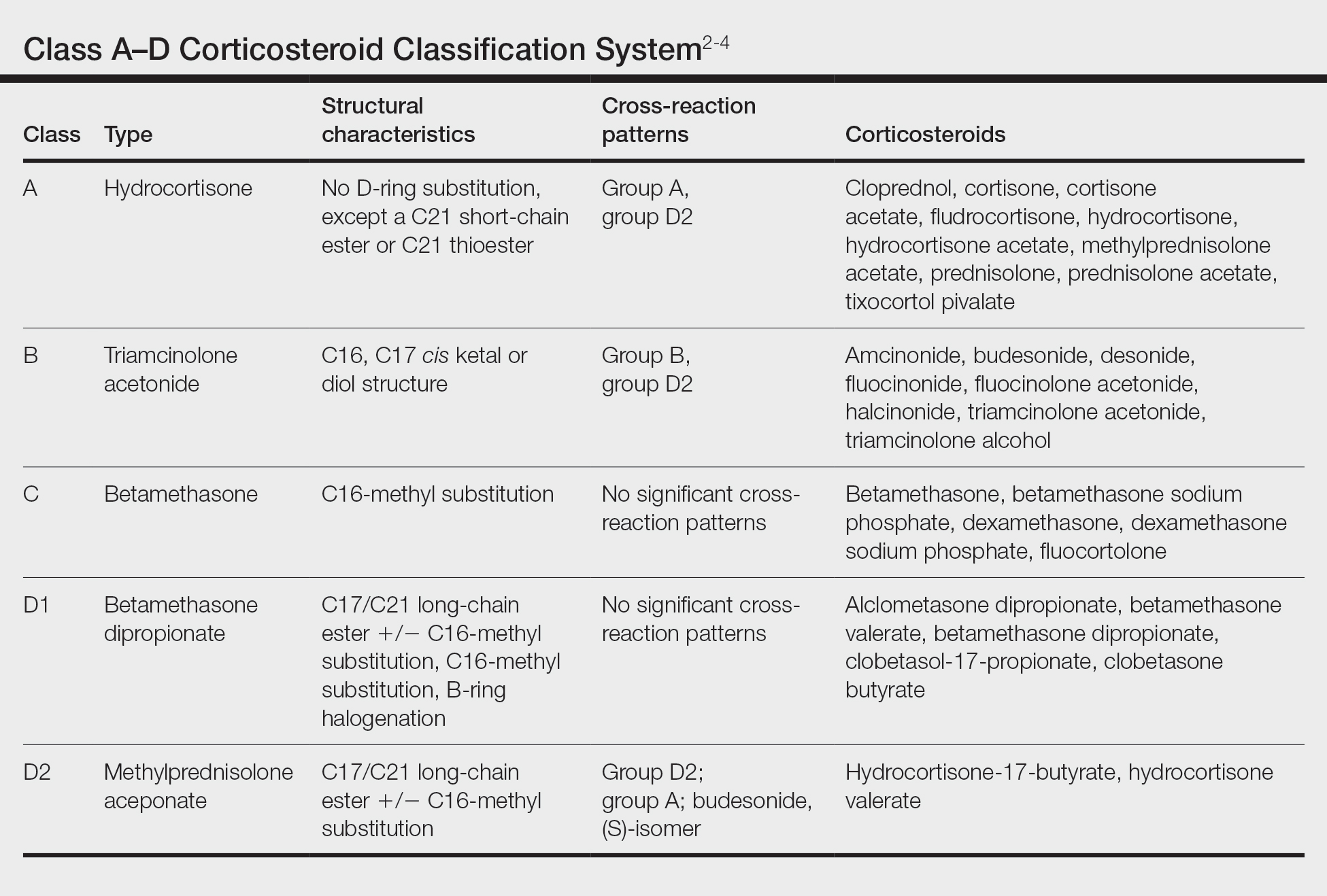

Traditionally, corticosteroids are divided into 4 basic structural groups—classes A, B, C, and D—based on the Coopman et al2 classification (Table). The class D corticosteroids were further subdivided into classes D1, defined by C16-methyl substitution and halogenation of the B ring, and D2, which lacks the aforementioned substitutions.4 However, more recently Baeck et al5 simplified this classification into 3 main groups of steroids based on molecular modeling in combination with patch test results. Group 1 combines the nonmethylated and (mostly) nonhalogenated class A and D2 molecules plus budesonide; group 2 accounts for some halogenated class B molecules with the C16, C17 cis ketal or diol structure; and group 3 includes halogenated and C16-methylated molecules from classes C and D1.4 For the purposes of this review, discussion of classes A through D refers to the Coopman et al2 classification, and groups 1 through 3 refers to Baeck et al.5

Tixocortol pivalate is used as a surrogate marker for hydrocortisone allergy and other class A corticosteroids and is part of the group 1 steroid classification. Interestingly, patients with TP-positive patch tests may not exhibit signs or symptoms of ACD from the use of hydrocortisone products. Repeat open application testing (ROAT) or provocative use testing may elicit a positive response in these patients, especially with the use of hydrocortisone cream (vs ointment), likely due to greater transepidermal penetration.6 There is little consensus on the optimal concentration of TP for patch testing. Although TP 1% often is recommended, studies have shown mixed findings of notable differences between high (1% petrolatum) and low (0.1% petrolatum) concentrations of TP.7,8

Budesonide also is part of group 1 and is a marker for contact allergy to class B corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone and fluocinonide. Cross-reactions between budesonide and other corticosteroids traditionally classified as group B may be explained by structural similarities, whereas cross-reactions with certain class D corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone-17-butyrate, may be better explained by the diastereomer composition of budesonide.9,10 In a European study, budesonide 0.01% and TP 0.1% included in the European Baseline Series detected 85% (23/27) of cases of corticosteroid allergies.11 Use of inhaled budesonide can provoke recall dermatitis and therefore should be avoided in allergic patients.12

Testing for ACD to topical steroids is complex, as the potent anti-inflammatory properties of these medications can complicate results. Selecting the appropriate test, vehicle, and concentration can help avoid false negatives. Although intradermal testing previously was thought to be superior to patch testing in detecting topical corticosteroid contact allergy, newer data have demonstrated strong concordance between the two methods.13,14 The risk for skin atrophy, particularly with the use of suspensions, limits the use of intradermal testing.14 An ethanol vehicle is recommended for patch testing, except when testing with TP or budesonide when petrolatum provides greater corticosteroid stability.14-16 An irritant pattern or a rim effect on patch testing often is considered positive when testing corticosteroids, as the effect of the steroid itself can diminish a positive reaction. As a result, 0.1% dilutions sometimes are favored over 1% test concentrations.14,15,17 Late readings (>7 days) may be necessary to detect positive reactions in both adults and children.18,19

The authors (M.R., A.R.A.) find these varied classifications of steroids daunting (and somewhat confusing!). In general, when ACD to topical steroids is suspected, in addition to standard patch testing with a corticosteroid series, ROAT of the suspected steroid may be necessary, as the rules of steroid classification may not be reproducible in the real world. For patients with only corticosteroid allergy, calcineurin inhibitors are a safe alternative.

Immunomodulators

Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analogue commonly used to treat psoriasis. Although it is a well-known irritant, ACD to topical calcipotriol rarely has been reported.20-23 Topical calcipotriol does not seem to cross-react with other vitamin D analogues, including tacalcitol and calcitriol.21,24 Based on the literature and the nonirritant reactive thresholds described by Fullerton et al,25 recommended patch test concentrations of calcipotriol in isopropanol are 2 to 10 µg/mL. Given its immunomodulating effects, calcipotriol may suppress contact hypersensitization from other allergens, similar to the effects seen with UV radiation.26

Calcineurin inhibitors act on the nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling pathway, resulting in downstream suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. Contact allergy to these topical medications is rare and mainly has involved pimecrolimus.27-30 In one case, a patient with a previously documented topical tacrolimus contact allergy demonstrated cross-reactivity with pimecrolimus on a double-blinded, right-vs-left ROAT, as well as by patch testing with pimecrolimus cream 1%, which was only weakly positive (+).27 Patch test concentrations of 2.5% or higher may be required to elicit positive reactions to tacrolimus, as shown in one case where this was attributed to high molecular weight and poor extrafacial skin absorption of tacrolimus.30 In an unusual case, a patient reacted positively to patch testing and ROAT using pimecrolimus cream 1% but not pimecrolimus 1% to 5% in petrolatum or alcohol nor the individual excipients, illustrating the importance of testing with both active and inactive ingredients.29

Anesthetics

Local anesthetics can be separated into 2 main groups—amides and esters—based on their chemical structures. From 2001 to 2004, the NACDG patch tested 10,061 patients and found 344 (3.4%) with a positive reaction to at least one topical anesthetic.31 We will discuss some of the allergic cutaneous reactions associated with topical benzocaine (an ester) and lidocaine and prilocaine (amides).

According to the NACDG, the estimated prevalence of topical benzocaine allergy from 2001 to 2018 was roughly 3%.32 Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in patients who used topical benzocaine to treat localized pain disorders, including herpes zoster and dental pain.33,34 Benzocaine may be used in the anogenital region in the form of antihemorrhoidal creams and in condoms and is a considerably more common allergen in those with anogenital dermatitis compared to those without.35-38 Although cross-reactions within the same anesthetic group are common, clinicians also should be aware of the potential for concomitant sensitivity between unrelated local anesthetics.39-41

From 2001 to 2018, the prevalence of ACD to topical lidocaine was estimated to be 7.9%, according to the NACDG.32 A topical anesthetic containing both lidocaine and prilocaine often is used preprocedurally and can be a source of ACD. Interestingly, several cases of ACD to combination lidocaine/prilocaine cream demonstrated positive patch tests to prilocaine but not lidocaine, despite their structural similarities.42-44 One case report described simultaneous positive reactions to both prilocaine 5% and lidocaine 1%.45

There are a few key points to consider when working up contact allergy to local anesthetics. Patients who develop positive patch test reactions to a local anesthetic should undergo further testing to better understand alternatives and future use. As previously mentioned, ACD to one anesthetic does not necessarily preclude the use of other related anesthetics. Intradermal testing may help differentiate immediate and delayed-type allergic reactions to local anesthetics and should therefore follow positive patch tests.46 Importantly, a delayed reading (ie, after day 6 or 7) also should be performed as part of intradermal testing. Patients with positive patch tests but negative intradermal test results may be able to tolerate systemic anesthetic use.47

Patch Testing for Potential Medicament ACD

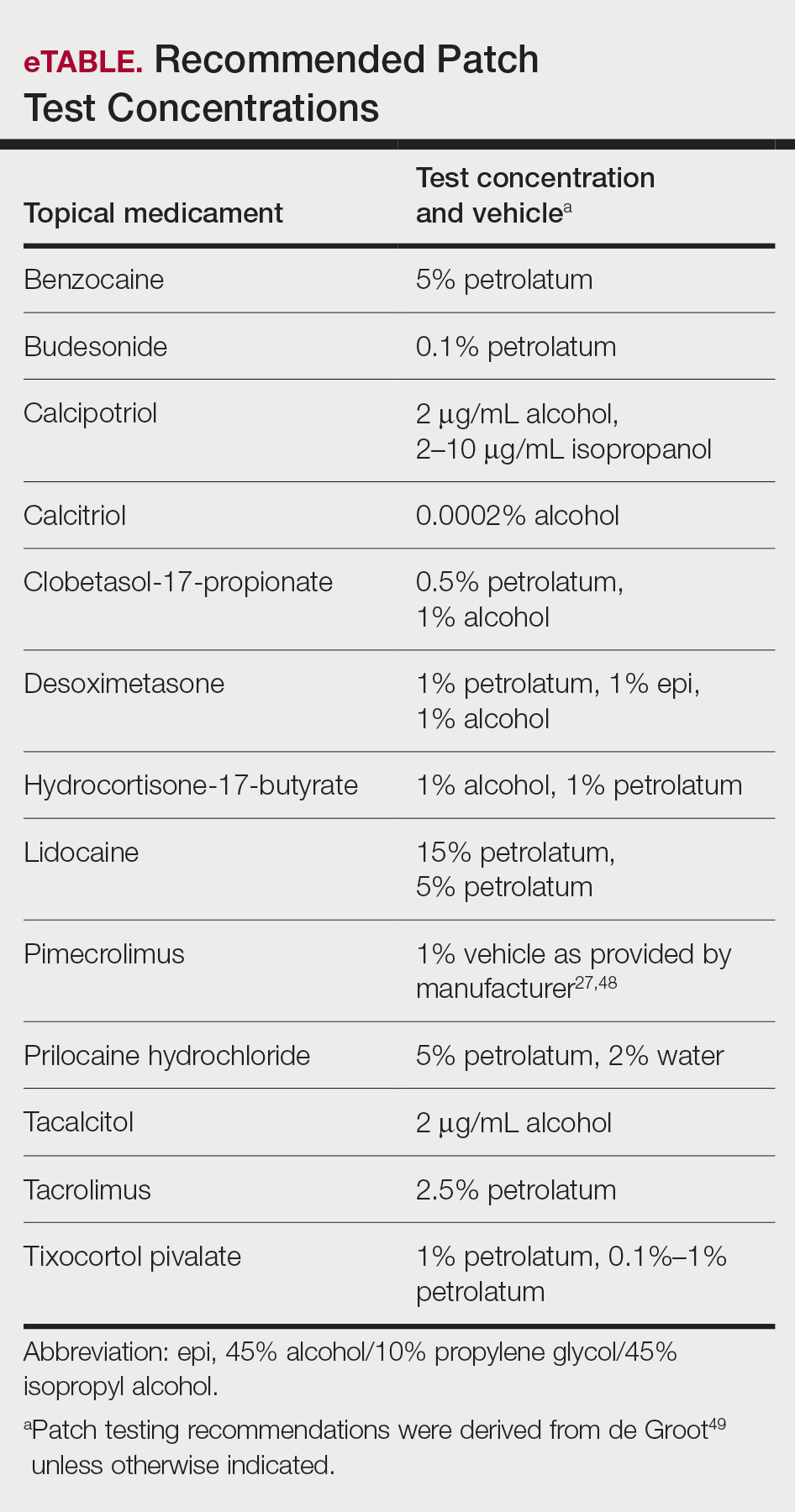

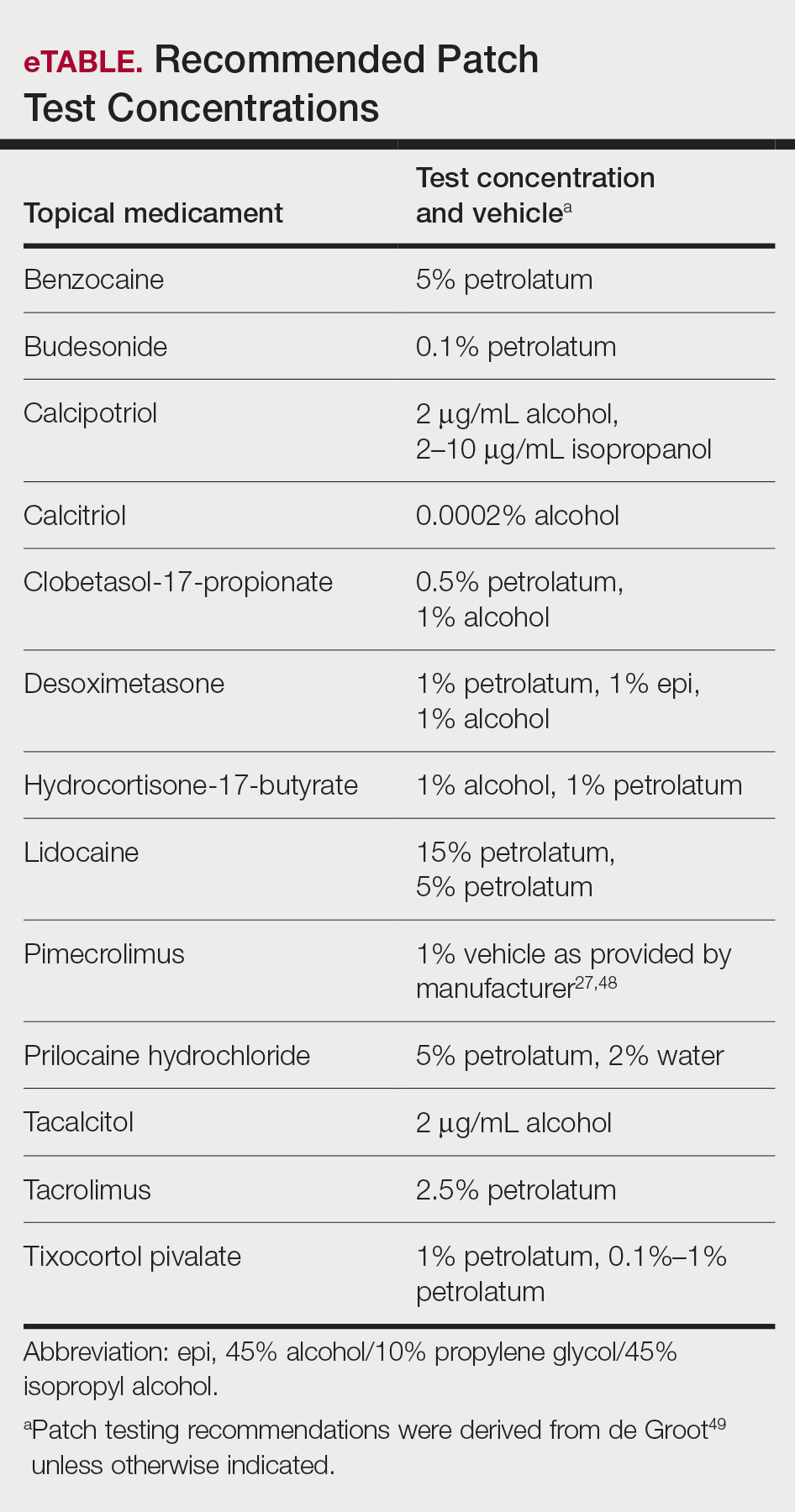

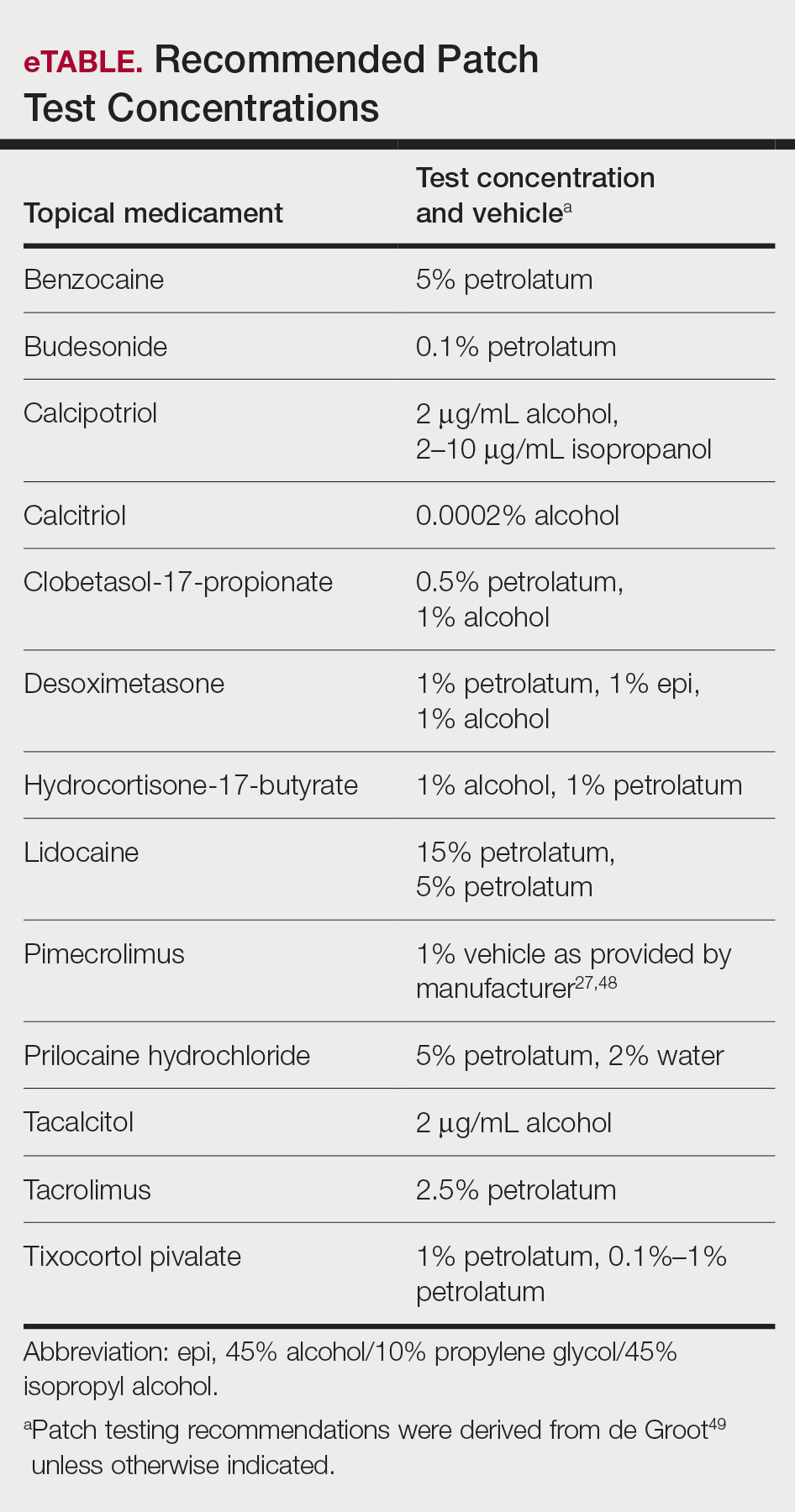

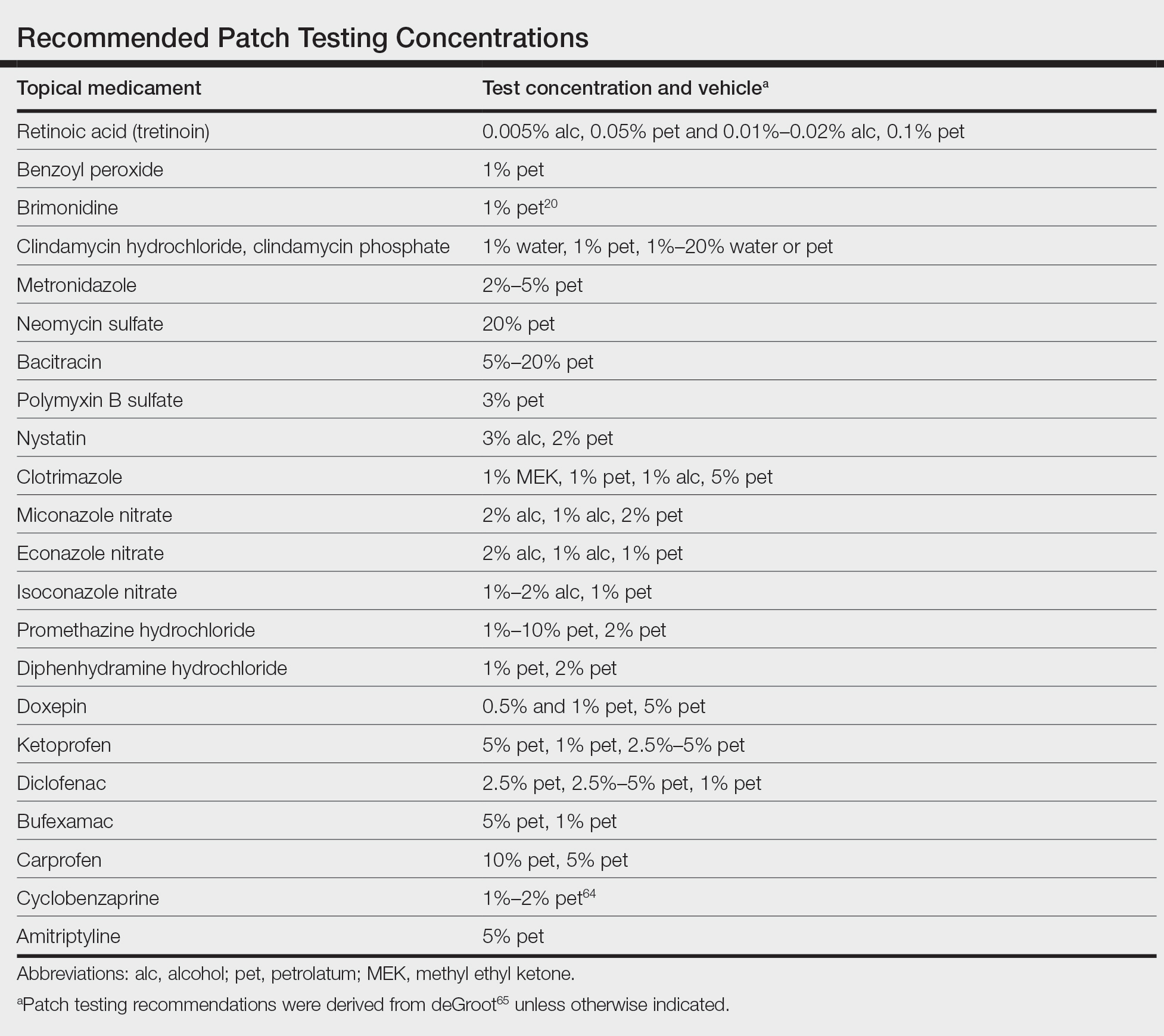

In this article, we touched on several topical medications that have nuanced patch testing specifications given their immunomodulating effects. A simplified outline of recommended patch test concentrations is provided in the eTable, and we encourage you to revisit these useful resources as needed. In many cases, referral to a specialized patch test clinic may be necessary. Although they are not reviewed in this article, always consider inactive ingredients such as preservatives, softening agents, and emulsifiers in the setting of medicament dermatitis, as they also may be culprits of ACD.

Final Interpretation

In this 2-part series, we covered ACD to several common topical drugs with a focus on active ingredients as the source of allergy, and yet this is just the tip of the iceberg. Topical medicaments are prevalent in the field of dermatology, and associated cases of ACD have been reported proportionately. Consider ACD when topical medication efficacy plateaus, triggers new-onset dermatitis, or seems to exacerbate an underlying dermatitis.

- Pratt MD, Mufti A, Lipson J, et al. Patch test reactions to corticosteroids: retrospective analysis from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2007-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:58-63. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000251

- Coopman S, Degreef H, Dooms-Goossens A. Identification of cross-reaction patterns in allergic contact dermatitis from topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:27-34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01396.x

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.028

- Matura M, Goossens A. Contact allergy to corticosteroids. Allergy. 2000;55:698-704. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00121.x

- Baeck M, Chemelle JA, Goossens A, et al. Corticosteroid cross-reactivity: clinical and molecular modelling tools. Allergy. 2011;66:1367-1374. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02666.x

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI. Clinical relevance of tixocortol pivalate-positive patch tests and questionable bioequivalence of different hydrocortisone preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:369-375. doi:10.1111/cod.12066

- Kalavala M, Statham BN, Green CM, et al. Tixocortol pivalate: what is the right concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:44-46. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01136.x

- Chowdhury MM, Statham BN, Sansom JE, et al. Patch testing for corticosteroid allergy with low and high concentrations of tixocortol pivalate and budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:311-312. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460519.x

- Isaksson M, Bruze M, Lepoittevin JP, et al. Patch testing with serial dilutions of budesonide, its R and S diastereomers, and potentially cross-reacting substances. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:170-176.

- Ferguson AD, Emerson RM, English JS. Cross-reactivity patterns to budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:337-340. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470604.x

- Kot M, Bogaczewicz J, Kre˛cisz B, et al. Contact allergy in the population of patients with chronic inflammatory dermatoses and contact hypersensitivity to corticosteroids. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:253-259. doi:10.5114/ada.2017.67848

- Isaksson M, Bruze M. Allergic contact dermatitis in response to budesonide reactivated by inhalation of the allergen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:880-885. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120464

- Mimesh S, Pratt M. Allergic contact dermatitis from corticosteroids: reproducibility of patch testing and correlation with intradermal testing. Dermatitis. 2006;17:137-142. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.05048

- Soria A, Baeck M, Goossens A, et al. Patch, prick or intradermal tests to detect delayed hypersensitivity to corticosteroids?. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:313-324. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01888.x

- Wilkinson SM, Beck MH. Corticosteroid contact hypersensitivity: what vehicle and concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:305-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02212.x

- Isaksson M, Beck MH, Wilkinson SM. Comparative testing with budesonide in petrolatum and ethanol in a standard series. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:123-124. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_16.x

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Immediate and delayed allergic hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: practical guidelines. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:38-45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01967.x

- Isaksson M. Corticosteroid contact allergy—the importance of late readings and testing with corticosteroids used by the patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:56-57. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00959.x

- Tam I, Yu J. Delayed patch test reaction to budesonide in an 8-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:690-691. doi:10.1111/pde.14168

- Garcia-Bravo B, Camacho F. Two cases of contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol cream. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:118-119.

- Zollner TM, Ochsendorf FR, Hensel O, et al. Delayed-type reactivity to calcipotriol without cross-sensitization to tacalcitol. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:251. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb02457.x

- Frosch PJ, Rustemeyer T. Contact allergy to calcipotriol does exist. report of an unequivocal case and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40:66-71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb05993.x

- Gilissen L, Huygens S, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:139-142. doi:10.1111/cod.12910

- Foti C, Carnimeo L, Bonamonte D, et al. Tolerance to calcitriol and tacalcitol in three patients with allergic contact dermatitis to calcipotriol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:756-759.

- Fullerton A, Benfeldt E, Petersen JR, et al. The calcipotriol dose-irritation relationship: 48-hour occlusive testing in healthy volunteers using Finn Chambers. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:259-265. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02071.x

- Hanneman KK, Scull HM, Cooper KD, et al. Effect of topical vitamin D analogue on in vivo contact sensitization. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1332-1334. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1332

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI, Eichenfield LF. Allergic contact dermatitis from pimecrolimus in a patient with tacrolimus allergy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.033

- Saitta P, Brancaccio R. Allergic contact dermatitis to pimecrolimus. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:43-44. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00822.x

- Neczyporenko F, Blondeel A. Allergic contact dermatitis to Elidel cream itself? Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:171-172. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01764.x

- Shaw DW, Eichenfield LF, Shainhouse T, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from tacrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:962-965. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.013

- Warshaw EM, Schram SE, Belsito DV, et al. Patch-test reactions to topical anesthetics: retrospective analysis of cross-sectional data, 2001 to 2004. Dermatitis. 2008;19:81-85.

- Warshaw EM, Shaver RL, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch test reactions associated with topical medications: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data (2001-2018)[published online September 1, 2021]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000777

- Roos TC, Merk HF. Allergic contact dermatitis from benzocaine ointment during treatment of herpes zoster. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:104. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.4402097.x

- González-Rodríguez AJ, Gutiérrez-Paredes EM, Revert Fernández Á, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to benzocaine: the importance of concomitant positive patch test results. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:156-158. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2011.07.023

- Muratore L, Calogiuri G, Foti C, et al. Contact allergy to benzocaine in a condom. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:173-174. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01359.x

- Sharma A, Agarwal S, Garg G, et al. Desire for lasting long in bed led to contact allergic dermatitis and subsequent superficial penile gangrene: a dreadful complication of benzocaine-containing extended-pleasure condom [published online September 27, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018227351. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-227351

- Bauer A, Geier J, Elsner P. Allergic contact dermatitis in patients with anogenital complaints. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:649-654.

- Warshaw EM, Kimyon RS, Silverberg JI, et al. Evaluation of patch test findings in patients with anogenital dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:85-91. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3844

- Weightman W, Turner T. Allergic contact dermatitis from lignocaine: report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:265-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05928.x

- Jovanovic´ M, Karadaglic´ D, Brkic´ S. Contact urticaria and allergic contact dermatitis to lidocaine in a patient sensitive to benzocaine and propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:124-126. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0560f.x

- Carazo JL, Morera BS, Colom LP, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from ethyl chloride and benzocaine. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E13-E15.

- le Coz CJ, Cribier BJ, Heid E. Patch testing in suspected allergic contact dermatitis due to EMLA cream in haemodialyzed patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:316-317. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02407.x

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00498e.x

- Pérez-Pérez LC, Fernández-Redondo V, Ginarte-Val M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream in a hemodialyzed patient. Dermatitis. 2006;17:85-87.

- Timmermans MW, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream: concomitant sensitization to both local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:237-238. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06932.x

- Fuzier R, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Mertes PM, et al. Immediate- and delayed-type allergic reactions to amide local anesthetics: clinical features and skin testing. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:595-601. doi:10.1002/pds.1758

- Ruzicka T, Gerstmeier M, Przybilla B, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics: comparison of patch test with prick and intradermal test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1202-1208. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70158-3

- Fowler JF Jr, Fowler L, Douglas JL, et al. Skin reactions to pimecrolimus cream 1% in patients allergic to propylene glycol: a double-blind randomized study. Dermatitis. 2007;18:134-139. doi:10.2310/6620.2007.06028

- de Groot A. Patch Testing. 3rd ed. acdegroot publishing; 2008.

In the first part of this 2-part series (Cutis. 2021;108:271-275), we discussed topical medicament allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) from acne and rosacea medications, antimicrobials, antihistamines, and topical pain preparations. In part 2 of this series, we focus on topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anesthetics.

Corticosteroids

Given their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, topical corticosteroids are utilized for the treatment of contact dermatitis and yet also are frequent culprits of ACD. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) demonstrated a 4% frequency of positive patch tests to at least one corticosteroid from 2007 to 2014; the relevant allergens were tixocortol pivalate (TP)(2.3%), budesonide (0.9%), hydrocortisone-17-butyrate (0.4%), clobetasol-17-propionate (0.3%), and desoximetasone (0.2%).1 Corticosteroid contact allergy can be difficult to recognize and may present as a flare of the underlying condition being treated. Clinically, these rashes may demonstrate an edge effect, characterized by pronounced dermatitis adjacent to and surrounding the treatment area due to concentrated anti-inflammatory effects in the center.

Traditionally, corticosteroids are divided into 4 basic structural groups—classes A, B, C, and D—based on the Coopman et al2 classification (Table). The class D corticosteroids were further subdivided into classes D1, defined by C16-methyl substitution and halogenation of the B ring, and D2, which lacks the aforementioned substitutions.4 However, more recently Baeck et al5 simplified this classification into 3 main groups of steroids based on molecular modeling in combination with patch test results. Group 1 combines the nonmethylated and (mostly) nonhalogenated class A and D2 molecules plus budesonide; group 2 accounts for some halogenated class B molecules with the C16, C17 cis ketal or diol structure; and group 3 includes halogenated and C16-methylated molecules from classes C and D1.4 For the purposes of this review, discussion of classes A through D refers to the Coopman et al2 classification, and groups 1 through 3 refers to Baeck et al.5

Tixocortol pivalate is used as a surrogate marker for hydrocortisone allergy and other class A corticosteroids and is part of the group 1 steroid classification. Interestingly, patients with TP-positive patch tests may not exhibit signs or symptoms of ACD from the use of hydrocortisone products. Repeat open application testing (ROAT) or provocative use testing may elicit a positive response in these patients, especially with the use of hydrocortisone cream (vs ointment), likely due to greater transepidermal penetration.6 There is little consensus on the optimal concentration of TP for patch testing. Although TP 1% often is recommended, studies have shown mixed findings of notable differences between high (1% petrolatum) and low (0.1% petrolatum) concentrations of TP.7,8

Budesonide also is part of group 1 and is a marker for contact allergy to class B corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone and fluocinonide. Cross-reactions between budesonide and other corticosteroids traditionally classified as group B may be explained by structural similarities, whereas cross-reactions with certain class D corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone-17-butyrate, may be better explained by the diastereomer composition of budesonide.9,10 In a European study, budesonide 0.01% and TP 0.1% included in the European Baseline Series detected 85% (23/27) of cases of corticosteroid allergies.11 Use of inhaled budesonide can provoke recall dermatitis and therefore should be avoided in allergic patients.12

Testing for ACD to topical steroids is complex, as the potent anti-inflammatory properties of these medications can complicate results. Selecting the appropriate test, vehicle, and concentration can help avoid false negatives. Although intradermal testing previously was thought to be superior to patch testing in detecting topical corticosteroid contact allergy, newer data have demonstrated strong concordance between the two methods.13,14 The risk for skin atrophy, particularly with the use of suspensions, limits the use of intradermal testing.14 An ethanol vehicle is recommended for patch testing, except when testing with TP or budesonide when petrolatum provides greater corticosteroid stability.14-16 An irritant pattern or a rim effect on patch testing often is considered positive when testing corticosteroids, as the effect of the steroid itself can diminish a positive reaction. As a result, 0.1% dilutions sometimes are favored over 1% test concentrations.14,15,17 Late readings (>7 days) may be necessary to detect positive reactions in both adults and children.18,19

The authors (M.R., A.R.A.) find these varied classifications of steroids daunting (and somewhat confusing!). In general, when ACD to topical steroids is suspected, in addition to standard patch testing with a corticosteroid series, ROAT of the suspected steroid may be necessary, as the rules of steroid classification may not be reproducible in the real world. For patients with only corticosteroid allergy, calcineurin inhibitors are a safe alternative.

Immunomodulators

Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analogue commonly used to treat psoriasis. Although it is a well-known irritant, ACD to topical calcipotriol rarely has been reported.20-23 Topical calcipotriol does not seem to cross-react with other vitamin D analogues, including tacalcitol and calcitriol.21,24 Based on the literature and the nonirritant reactive thresholds described by Fullerton et al,25 recommended patch test concentrations of calcipotriol in isopropanol are 2 to 10 µg/mL. Given its immunomodulating effects, calcipotriol may suppress contact hypersensitization from other allergens, similar to the effects seen with UV radiation.26

Calcineurin inhibitors act on the nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling pathway, resulting in downstream suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. Contact allergy to these topical medications is rare and mainly has involved pimecrolimus.27-30 In one case, a patient with a previously documented topical tacrolimus contact allergy demonstrated cross-reactivity with pimecrolimus on a double-blinded, right-vs-left ROAT, as well as by patch testing with pimecrolimus cream 1%, which was only weakly positive (+).27 Patch test concentrations of 2.5% or higher may be required to elicit positive reactions to tacrolimus, as shown in one case where this was attributed to high molecular weight and poor extrafacial skin absorption of tacrolimus.30 In an unusual case, a patient reacted positively to patch testing and ROAT using pimecrolimus cream 1% but not pimecrolimus 1% to 5% in petrolatum or alcohol nor the individual excipients, illustrating the importance of testing with both active and inactive ingredients.29

Anesthetics

Local anesthetics can be separated into 2 main groups—amides and esters—based on their chemical structures. From 2001 to 2004, the NACDG patch tested 10,061 patients and found 344 (3.4%) with a positive reaction to at least one topical anesthetic.31 We will discuss some of the allergic cutaneous reactions associated with topical benzocaine (an ester) and lidocaine and prilocaine (amides).

According to the NACDG, the estimated prevalence of topical benzocaine allergy from 2001 to 2018 was roughly 3%.32 Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in patients who used topical benzocaine to treat localized pain disorders, including herpes zoster and dental pain.33,34 Benzocaine may be used in the anogenital region in the form of antihemorrhoidal creams and in condoms and is a considerably more common allergen in those with anogenital dermatitis compared to those without.35-38 Although cross-reactions within the same anesthetic group are common, clinicians also should be aware of the potential for concomitant sensitivity between unrelated local anesthetics.39-41

From 2001 to 2018, the prevalence of ACD to topical lidocaine was estimated to be 7.9%, according to the NACDG.32 A topical anesthetic containing both lidocaine and prilocaine often is used preprocedurally and can be a source of ACD. Interestingly, several cases of ACD to combination lidocaine/prilocaine cream demonstrated positive patch tests to prilocaine but not lidocaine, despite their structural similarities.42-44 One case report described simultaneous positive reactions to both prilocaine 5% and lidocaine 1%.45

There are a few key points to consider when working up contact allergy to local anesthetics. Patients who develop positive patch test reactions to a local anesthetic should undergo further testing to better understand alternatives and future use. As previously mentioned, ACD to one anesthetic does not necessarily preclude the use of other related anesthetics. Intradermal testing may help differentiate immediate and delayed-type allergic reactions to local anesthetics and should therefore follow positive patch tests.46 Importantly, a delayed reading (ie, after day 6 or 7) also should be performed as part of intradermal testing. Patients with positive patch tests but negative intradermal test results may be able to tolerate systemic anesthetic use.47

Patch Testing for Potential Medicament ACD

In this article, we touched on several topical medications that have nuanced patch testing specifications given their immunomodulating effects. A simplified outline of recommended patch test concentrations is provided in the eTable, and we encourage you to revisit these useful resources as needed. In many cases, referral to a specialized patch test clinic may be necessary. Although they are not reviewed in this article, always consider inactive ingredients such as preservatives, softening agents, and emulsifiers in the setting of medicament dermatitis, as they also may be culprits of ACD.

Final Interpretation

In this 2-part series, we covered ACD to several common topical drugs with a focus on active ingredients as the source of allergy, and yet this is just the tip of the iceberg. Topical medicaments are prevalent in the field of dermatology, and associated cases of ACD have been reported proportionately. Consider ACD when topical medication efficacy plateaus, triggers new-onset dermatitis, or seems to exacerbate an underlying dermatitis.

In the first part of this 2-part series (Cutis. 2021;108:271-275), we discussed topical medicament allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) from acne and rosacea medications, antimicrobials, antihistamines, and topical pain preparations. In part 2 of this series, we focus on topical corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and anesthetics.

Corticosteroids

Given their anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects, topical corticosteroids are utilized for the treatment of contact dermatitis and yet also are frequent culprits of ACD. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) demonstrated a 4% frequency of positive patch tests to at least one corticosteroid from 2007 to 2014; the relevant allergens were tixocortol pivalate (TP)(2.3%), budesonide (0.9%), hydrocortisone-17-butyrate (0.4%), clobetasol-17-propionate (0.3%), and desoximetasone (0.2%).1 Corticosteroid contact allergy can be difficult to recognize and may present as a flare of the underlying condition being treated. Clinically, these rashes may demonstrate an edge effect, characterized by pronounced dermatitis adjacent to and surrounding the treatment area due to concentrated anti-inflammatory effects in the center.

Traditionally, corticosteroids are divided into 4 basic structural groups—classes A, B, C, and D—based on the Coopman et al2 classification (Table). The class D corticosteroids were further subdivided into classes D1, defined by C16-methyl substitution and halogenation of the B ring, and D2, which lacks the aforementioned substitutions.4 However, more recently Baeck et al5 simplified this classification into 3 main groups of steroids based on molecular modeling in combination with patch test results. Group 1 combines the nonmethylated and (mostly) nonhalogenated class A and D2 molecules plus budesonide; group 2 accounts for some halogenated class B molecules with the C16, C17 cis ketal or diol structure; and group 3 includes halogenated and C16-methylated molecules from classes C and D1.4 For the purposes of this review, discussion of classes A through D refers to the Coopman et al2 classification, and groups 1 through 3 refers to Baeck et al.5

Tixocortol pivalate is used as a surrogate marker for hydrocortisone allergy and other class A corticosteroids and is part of the group 1 steroid classification. Interestingly, patients with TP-positive patch tests may not exhibit signs or symptoms of ACD from the use of hydrocortisone products. Repeat open application testing (ROAT) or provocative use testing may elicit a positive response in these patients, especially with the use of hydrocortisone cream (vs ointment), likely due to greater transepidermal penetration.6 There is little consensus on the optimal concentration of TP for patch testing. Although TP 1% often is recommended, studies have shown mixed findings of notable differences between high (1% petrolatum) and low (0.1% petrolatum) concentrations of TP.7,8

Budesonide also is part of group 1 and is a marker for contact allergy to class B corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone and fluocinonide. Cross-reactions between budesonide and other corticosteroids traditionally classified as group B may be explained by structural similarities, whereas cross-reactions with certain class D corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone-17-butyrate, may be better explained by the diastereomer composition of budesonide.9,10 In a European study, budesonide 0.01% and TP 0.1% included in the European Baseline Series detected 85% (23/27) of cases of corticosteroid allergies.11 Use of inhaled budesonide can provoke recall dermatitis and therefore should be avoided in allergic patients.12

Testing for ACD to topical steroids is complex, as the potent anti-inflammatory properties of these medications can complicate results. Selecting the appropriate test, vehicle, and concentration can help avoid false negatives. Although intradermal testing previously was thought to be superior to patch testing in detecting topical corticosteroid contact allergy, newer data have demonstrated strong concordance between the two methods.13,14 The risk for skin atrophy, particularly with the use of suspensions, limits the use of intradermal testing.14 An ethanol vehicle is recommended for patch testing, except when testing with TP or budesonide when petrolatum provides greater corticosteroid stability.14-16 An irritant pattern or a rim effect on patch testing often is considered positive when testing corticosteroids, as the effect of the steroid itself can diminish a positive reaction. As a result, 0.1% dilutions sometimes are favored over 1% test concentrations.14,15,17 Late readings (>7 days) may be necessary to detect positive reactions in both adults and children.18,19

The authors (M.R., A.R.A.) find these varied classifications of steroids daunting (and somewhat confusing!). In general, when ACD to topical steroids is suspected, in addition to standard patch testing with a corticosteroid series, ROAT of the suspected steroid may be necessary, as the rules of steroid classification may not be reproducible in the real world. For patients with only corticosteroid allergy, calcineurin inhibitors are a safe alternative.

Immunomodulators

Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analogue commonly used to treat psoriasis. Although it is a well-known irritant, ACD to topical calcipotriol rarely has been reported.20-23 Topical calcipotriol does not seem to cross-react with other vitamin D analogues, including tacalcitol and calcitriol.21,24 Based on the literature and the nonirritant reactive thresholds described by Fullerton et al,25 recommended patch test concentrations of calcipotriol in isopropanol are 2 to 10 µg/mL. Given its immunomodulating effects, calcipotriol may suppress contact hypersensitization from other allergens, similar to the effects seen with UV radiation.26

Calcineurin inhibitors act on the nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling pathway, resulting in downstream suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. Contact allergy to these topical medications is rare and mainly has involved pimecrolimus.27-30 In one case, a patient with a previously documented topical tacrolimus contact allergy demonstrated cross-reactivity with pimecrolimus on a double-blinded, right-vs-left ROAT, as well as by patch testing with pimecrolimus cream 1%, which was only weakly positive (+).27 Patch test concentrations of 2.5% or higher may be required to elicit positive reactions to tacrolimus, as shown in one case where this was attributed to high molecular weight and poor extrafacial skin absorption of tacrolimus.30 In an unusual case, a patient reacted positively to patch testing and ROAT using pimecrolimus cream 1% but not pimecrolimus 1% to 5% in petrolatum or alcohol nor the individual excipients, illustrating the importance of testing with both active and inactive ingredients.29

Anesthetics

Local anesthetics can be separated into 2 main groups—amides and esters—based on their chemical structures. From 2001 to 2004, the NACDG patch tested 10,061 patients and found 344 (3.4%) with a positive reaction to at least one topical anesthetic.31 We will discuss some of the allergic cutaneous reactions associated with topical benzocaine (an ester) and lidocaine and prilocaine (amides).

According to the NACDG, the estimated prevalence of topical benzocaine allergy from 2001 to 2018 was roughly 3%.32 Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in patients who used topical benzocaine to treat localized pain disorders, including herpes zoster and dental pain.33,34 Benzocaine may be used in the anogenital region in the form of antihemorrhoidal creams and in condoms and is a considerably more common allergen in those with anogenital dermatitis compared to those without.35-38 Although cross-reactions within the same anesthetic group are common, clinicians also should be aware of the potential for concomitant sensitivity between unrelated local anesthetics.39-41

From 2001 to 2018, the prevalence of ACD to topical lidocaine was estimated to be 7.9%, according to the NACDG.32 A topical anesthetic containing both lidocaine and prilocaine often is used preprocedurally and can be a source of ACD. Interestingly, several cases of ACD to combination lidocaine/prilocaine cream demonstrated positive patch tests to prilocaine but not lidocaine, despite their structural similarities.42-44 One case report described simultaneous positive reactions to both prilocaine 5% and lidocaine 1%.45

There are a few key points to consider when working up contact allergy to local anesthetics. Patients who develop positive patch test reactions to a local anesthetic should undergo further testing to better understand alternatives and future use. As previously mentioned, ACD to one anesthetic does not necessarily preclude the use of other related anesthetics. Intradermal testing may help differentiate immediate and delayed-type allergic reactions to local anesthetics and should therefore follow positive patch tests.46 Importantly, a delayed reading (ie, after day 6 or 7) also should be performed as part of intradermal testing. Patients with positive patch tests but negative intradermal test results may be able to tolerate systemic anesthetic use.47

Patch Testing for Potential Medicament ACD

In this article, we touched on several topical medications that have nuanced patch testing specifications given their immunomodulating effects. A simplified outline of recommended patch test concentrations is provided in the eTable, and we encourage you to revisit these useful resources as needed. In many cases, referral to a specialized patch test clinic may be necessary. Although they are not reviewed in this article, always consider inactive ingredients such as preservatives, softening agents, and emulsifiers in the setting of medicament dermatitis, as they also may be culprits of ACD.

Final Interpretation

In this 2-part series, we covered ACD to several common topical drugs with a focus on active ingredients as the source of allergy, and yet this is just the tip of the iceberg. Topical medicaments are prevalent in the field of dermatology, and associated cases of ACD have been reported proportionately. Consider ACD when topical medication efficacy plateaus, triggers new-onset dermatitis, or seems to exacerbate an underlying dermatitis.

- Pratt MD, Mufti A, Lipson J, et al. Patch test reactions to corticosteroids: retrospective analysis from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2007-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:58-63. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000251

- Coopman S, Degreef H, Dooms-Goossens A. Identification of cross-reaction patterns in allergic contact dermatitis from topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:27-34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01396.x

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.028

- Matura M, Goossens A. Contact allergy to corticosteroids. Allergy. 2000;55:698-704. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00121.x

- Baeck M, Chemelle JA, Goossens A, et al. Corticosteroid cross-reactivity: clinical and molecular modelling tools. Allergy. 2011;66:1367-1374. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02666.x

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI. Clinical relevance of tixocortol pivalate-positive patch tests and questionable bioequivalence of different hydrocortisone preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:369-375. doi:10.1111/cod.12066

- Kalavala M, Statham BN, Green CM, et al. Tixocortol pivalate: what is the right concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:44-46. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01136.x

- Chowdhury MM, Statham BN, Sansom JE, et al. Patch testing for corticosteroid allergy with low and high concentrations of tixocortol pivalate and budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:311-312. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460519.x

- Isaksson M, Bruze M, Lepoittevin JP, et al. Patch testing with serial dilutions of budesonide, its R and S diastereomers, and potentially cross-reacting substances. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:170-176.

- Ferguson AD, Emerson RM, English JS. Cross-reactivity patterns to budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:337-340. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470604.x

- Kot M, Bogaczewicz J, Kre˛cisz B, et al. Contact allergy in the population of patients with chronic inflammatory dermatoses and contact hypersensitivity to corticosteroids. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:253-259. doi:10.5114/ada.2017.67848

- Isaksson M, Bruze M. Allergic contact dermatitis in response to budesonide reactivated by inhalation of the allergen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:880-885. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120464

- Mimesh S, Pratt M. Allergic contact dermatitis from corticosteroids: reproducibility of patch testing and correlation with intradermal testing. Dermatitis. 2006;17:137-142. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.05048

- Soria A, Baeck M, Goossens A, et al. Patch, prick or intradermal tests to detect delayed hypersensitivity to corticosteroids?. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:313-324. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01888.x

- Wilkinson SM, Beck MH. Corticosteroid contact hypersensitivity: what vehicle and concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:305-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02212.x

- Isaksson M, Beck MH, Wilkinson SM. Comparative testing with budesonide in petrolatum and ethanol in a standard series. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:123-124. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_16.x

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Immediate and delayed allergic hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: practical guidelines. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:38-45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01967.x

- Isaksson M. Corticosteroid contact allergy—the importance of late readings and testing with corticosteroids used by the patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:56-57. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00959.x

- Tam I, Yu J. Delayed patch test reaction to budesonide in an 8-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:690-691. doi:10.1111/pde.14168

- Garcia-Bravo B, Camacho F. Two cases of contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol cream. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:118-119.

- Zollner TM, Ochsendorf FR, Hensel O, et al. Delayed-type reactivity to calcipotriol without cross-sensitization to tacalcitol. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:251. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb02457.x

- Frosch PJ, Rustemeyer T. Contact allergy to calcipotriol does exist. report of an unequivocal case and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40:66-71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb05993.x

- Gilissen L, Huygens S, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:139-142. doi:10.1111/cod.12910

- Foti C, Carnimeo L, Bonamonte D, et al. Tolerance to calcitriol and tacalcitol in three patients with allergic contact dermatitis to calcipotriol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:756-759.

- Fullerton A, Benfeldt E, Petersen JR, et al. The calcipotriol dose-irritation relationship: 48-hour occlusive testing in healthy volunteers using Finn Chambers. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:259-265. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02071.x

- Hanneman KK, Scull HM, Cooper KD, et al. Effect of topical vitamin D analogue on in vivo contact sensitization. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1332-1334. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1332

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI, Eichenfield LF. Allergic contact dermatitis from pimecrolimus in a patient with tacrolimus allergy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.033

- Saitta P, Brancaccio R. Allergic contact dermatitis to pimecrolimus. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:43-44. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00822.x

- Neczyporenko F, Blondeel A. Allergic contact dermatitis to Elidel cream itself? Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:171-172. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01764.x

- Shaw DW, Eichenfield LF, Shainhouse T, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from tacrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:962-965. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.013

- Warshaw EM, Schram SE, Belsito DV, et al. Patch-test reactions to topical anesthetics: retrospective analysis of cross-sectional data, 2001 to 2004. Dermatitis. 2008;19:81-85.

- Warshaw EM, Shaver RL, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch test reactions associated with topical medications: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data (2001-2018)[published online September 1, 2021]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000777

- Roos TC, Merk HF. Allergic contact dermatitis from benzocaine ointment during treatment of herpes zoster. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:104. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.4402097.x

- González-Rodríguez AJ, Gutiérrez-Paredes EM, Revert Fernández Á, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to benzocaine: the importance of concomitant positive patch test results. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:156-158. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2011.07.023

- Muratore L, Calogiuri G, Foti C, et al. Contact allergy to benzocaine in a condom. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:173-174. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01359.x

- Sharma A, Agarwal S, Garg G, et al. Desire for lasting long in bed led to contact allergic dermatitis and subsequent superficial penile gangrene: a dreadful complication of benzocaine-containing extended-pleasure condom [published online September 27, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018227351. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-227351

- Bauer A, Geier J, Elsner P. Allergic contact dermatitis in patients with anogenital complaints. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:649-654.

- Warshaw EM, Kimyon RS, Silverberg JI, et al. Evaluation of patch test findings in patients with anogenital dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:85-91. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3844

- Weightman W, Turner T. Allergic contact dermatitis from lignocaine: report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:265-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05928.x

- Jovanovic´ M, Karadaglic´ D, Brkic´ S. Contact urticaria and allergic contact dermatitis to lidocaine in a patient sensitive to benzocaine and propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:124-126. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0560f.x

- Carazo JL, Morera BS, Colom LP, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from ethyl chloride and benzocaine. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E13-E15.

- le Coz CJ, Cribier BJ, Heid E. Patch testing in suspected allergic contact dermatitis due to EMLA cream in haemodialyzed patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:316-317. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02407.x

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00498e.x

- Pérez-Pérez LC, Fernández-Redondo V, Ginarte-Val M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream in a hemodialyzed patient. Dermatitis. 2006;17:85-87.

- Timmermans MW, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream: concomitant sensitization to both local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:237-238. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06932.x

- Fuzier R, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Mertes PM, et al. Immediate- and delayed-type allergic reactions to amide local anesthetics: clinical features and skin testing. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:595-601. doi:10.1002/pds.1758

- Ruzicka T, Gerstmeier M, Przybilla B, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics: comparison of patch test with prick and intradermal test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1202-1208. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70158-3

- Fowler JF Jr, Fowler L, Douglas JL, et al. Skin reactions to pimecrolimus cream 1% in patients allergic to propylene glycol: a double-blind randomized study. Dermatitis. 2007;18:134-139. doi:10.2310/6620.2007.06028

- de Groot A. Patch Testing. 3rd ed. acdegroot publishing; 2008.

- Pratt MD, Mufti A, Lipson J, et al. Patch test reactions to corticosteroids: retrospective analysis from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2007-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:58-63. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000251

- Coopman S, Degreef H, Dooms-Goossens A. Identification of cross-reaction patterns in allergic contact dermatitis from topical corticosteroids. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:27-34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01396.x

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.028

- Matura M, Goossens A. Contact allergy to corticosteroids. Allergy. 2000;55:698-704. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00121.x

- Baeck M, Chemelle JA, Goossens A, et al. Corticosteroid cross-reactivity: clinical and molecular modelling tools. Allergy. 2011;66:1367-1374. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02666.x

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI. Clinical relevance of tixocortol pivalate-positive patch tests and questionable bioequivalence of different hydrocortisone preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:369-375. doi:10.1111/cod.12066

- Kalavala M, Statham BN, Green CM, et al. Tixocortol pivalate: what is the right concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:44-46. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01136.x

- Chowdhury MM, Statham BN, Sansom JE, et al. Patch testing for corticosteroid allergy with low and high concentrations of tixocortol pivalate and budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:311-312. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460519.x

- Isaksson M, Bruze M, Lepoittevin JP, et al. Patch testing with serial dilutions of budesonide, its R and S diastereomers, and potentially cross-reacting substances. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:170-176.

- Ferguson AD, Emerson RM, English JS. Cross-reactivity patterns to budesonide. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:337-340. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470604.x

- Kot M, Bogaczewicz J, Kre˛cisz B, et al. Contact allergy in the population of patients with chronic inflammatory dermatoses and contact hypersensitivity to corticosteroids. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:253-259. doi:10.5114/ada.2017.67848

- Isaksson M, Bruze M. Allergic contact dermatitis in response to budesonide reactivated by inhalation of the allergen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:880-885. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120464

- Mimesh S, Pratt M. Allergic contact dermatitis from corticosteroids: reproducibility of patch testing and correlation with intradermal testing. Dermatitis. 2006;17:137-142. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.05048

- Soria A, Baeck M, Goossens A, et al. Patch, prick or intradermal tests to detect delayed hypersensitivity to corticosteroids?. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:313-324. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01888.x

- Wilkinson SM, Beck MH. Corticosteroid contact hypersensitivity: what vehicle and concentration? Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:305-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02212.x

- Isaksson M, Beck MH, Wilkinson SM. Comparative testing with budesonide in petrolatum and ethanol in a standard series. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:123-124. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_16.x

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Immediate and delayed allergic hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: practical guidelines. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:38-45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01967.x

- Isaksson M. Corticosteroid contact allergy—the importance of late readings and testing with corticosteroids used by the patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:56-57. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00959.x

- Tam I, Yu J. Delayed patch test reaction to budesonide in an 8-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:690-691. doi:10.1111/pde.14168

- Garcia-Bravo B, Camacho F. Two cases of contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol cream. Am J Contact Dermat. 1996;7:118-119.

- Zollner TM, Ochsendorf FR, Hensel O, et al. Delayed-type reactivity to calcipotriol without cross-sensitization to tacalcitol. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:251. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb02457.x

- Frosch PJ, Rustemeyer T. Contact allergy to calcipotriol does exist. report of an unequivocal case and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40:66-71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb05993.x

- Gilissen L, Huygens S, Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by calcipotriol. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:139-142. doi:10.1111/cod.12910

- Foti C, Carnimeo L, Bonamonte D, et al. Tolerance to calcitriol and tacalcitol in three patients with allergic contact dermatitis to calcipotriol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:756-759.

- Fullerton A, Benfeldt E, Petersen JR, et al. The calcipotriol dose-irritation relationship: 48-hour occlusive testing in healthy volunteers using Finn Chambers. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:259-265. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02071.x

- Hanneman KK, Scull HM, Cooper KD, et al. Effect of topical vitamin D analogue on in vivo contact sensitization. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1332-1334. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1332

- Shaw DW, Maibach HI, Eichenfield LF. Allergic contact dermatitis from pimecrolimus in a patient with tacrolimus allergy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.033

- Saitta P, Brancaccio R. Allergic contact dermatitis to pimecrolimus. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:43-44. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.00822.x

- Neczyporenko F, Blondeel A. Allergic contact dermatitis to Elidel cream itself? Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:171-172. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01764.x

- Shaw DW, Eichenfield LF, Shainhouse T, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from tacrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:962-965. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.013

- Warshaw EM, Schram SE, Belsito DV, et al. Patch-test reactions to topical anesthetics: retrospective analysis of cross-sectional data, 2001 to 2004. Dermatitis. 2008;19:81-85.

- Warshaw EM, Shaver RL, DeKoven JG, et al. Patch test reactions associated with topical medications: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data (2001-2018)[published online September 1, 2021]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000777

- Roos TC, Merk HF. Allergic contact dermatitis from benzocaine ointment during treatment of herpes zoster. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:104. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.4402097.x

- González-Rodríguez AJ, Gutiérrez-Paredes EM, Revert Fernández Á, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to benzocaine: the importance of concomitant positive patch test results. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:156-158. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2011.07.023

- Muratore L, Calogiuri G, Foti C, et al. Contact allergy to benzocaine in a condom. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:173-174. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01359.x

- Sharma A, Agarwal S, Garg G, et al. Desire for lasting long in bed led to contact allergic dermatitis and subsequent superficial penile gangrene: a dreadful complication of benzocaine-containing extended-pleasure condom [published online September 27, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018227351. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-227351

- Bauer A, Geier J, Elsner P. Allergic contact dermatitis in patients with anogenital complaints. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:649-654.

- Warshaw EM, Kimyon RS, Silverberg JI, et al. Evaluation of patch test findings in patients with anogenital dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:85-91. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3844

- Weightman W, Turner T. Allergic contact dermatitis from lignocaine: report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:265-266. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05928.x

- Jovanovic´ M, Karadaglic´ D, Brkic´ S. Contact urticaria and allergic contact dermatitis to lidocaine in a patient sensitive to benzocaine and propolis. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:124-126. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0560f.x

- Carazo JL, Morera BS, Colom LP, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from ethyl chloride and benzocaine. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E13-E15.

- le Coz CJ, Cribier BJ, Heid E. Patch testing in suspected allergic contact dermatitis due to EMLA cream in haemodialyzed patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:316-317. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02407.x

- Ismail F, Goldsmith PC. EMLA cream-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a child with thalassaemia major. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:111. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00498e.x

- Pérez-Pérez LC, Fernández-Redondo V, Ginarte-Val M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream in a hemodialyzed patient. Dermatitis. 2006;17:85-87.

- Timmermans MW, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Allergic contact dermatitis from EMLA cream: concomitant sensitization to both local anesthetics lidocaine and prilocaine. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:237-238. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06932.x

- Fuzier R, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Mertes PM, et al. Immediate- and delayed-type allergic reactions to amide local anesthetics: clinical features and skin testing. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:595-601. doi:10.1002/pds.1758

- Ruzicka T, Gerstmeier M, Przybilla B, et al. Allergy to local anesthetics: comparison of patch test with prick and intradermal test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1202-1208. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70158-3

- Fowler JF Jr, Fowler L, Douglas JL, et al. Skin reactions to pimecrolimus cream 1% in patients allergic to propylene glycol: a double-blind randomized study. Dermatitis. 2007;18:134-139. doi:10.2310/6620.2007.06028

- de Groot A. Patch Testing. 3rd ed. acdegroot publishing; 2008.

Practice Points

- Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) should be suspected in patients with persistent or worsening dermatitis after use of topical medications.

- Cross-reactions commonly occur between structurally similar compounds and occasionally between molecules from different drug classes.

- Some cases of topical medicament ACD remain elusive after patch testing, particularly drugs with potent immunomodulating effects.

Contact Allergy to Topical Medicaments, Part 1: A Double-edged Sword

Topical medications frequently are prescribed in dermatology and provide the advantages of direct skin penetration and targeted application while typically sparing patients from systemic effects. Adverse cutaneous effects include allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), irritant contact dermatitis (ICD), photosensitivity, urticaria, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, atrophy, periorificial dermatitis, and acneform eruptions. Allergic contact dermatitis can develop from the active drug or vehicle components.

Patients with medicament ACD often present with symptoms of pruritus and dermatitis at the site of topical application. They may express concern that the medication is no longer working or seems to be making things worse. Certain sites are more prone to developing medicament dermatitis, including the face, groin, and lower legs. Older adults may be more at risk. Other risk factors include pre-existing skin diseases such as stasis dermatitis, acne, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and genital dermatoses.1 A review of 14,911 patch-tested patients from a single referral clinic revealed that 17.4% had iatrogenic contact dermatitis, with the most common culprits being topical antibiotics, antiseptics, and steroids.2

In this 2-part series, we will focus on the active drug as a source of ACD. Part 1 explores ACD associated with acne and rosacea medications, antimicrobials, antihistamines, and topical pain preparations.

Acne and Rosacea Medications

Retinoids—Topical retinoids are first-line acne treatments that help normalize skin keratinization. Irritant contact dermatitis from retinoids is a well-known and common side effect. Although far less common than ICD, ACD from topical retinoid use has been reported.3,4 Reactions to tretinoin are most frequently reported in the literature compared to adapalene gel5 and tazarotene foam, which have lower potential for sensitization.6 Allergic contact dermatitis also has been reported from retinyl palmitate7,8 in cosmetic creams and from occupational exposure in settings of industrial vitamin A production.9 Both ICD and ACD from topical retinoids can present with pruritus, erythema, and scaling. Given this clinical overlap between ACD and ICD, patch testing is crucial in differentiating the underlying etiology of the dermatitis.

Benzoyl Peroxide—Benzoyl peroxide (BP) is another popular topical acne treatment that targets Cutibacterium acnes, a bacterium often implicated in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Similar to retinoids, ICD is more common than ACD. Several cases of ACD to BP have been reported.10-14 Occasionally, honey-colored crusting associated with ACD to BP can mimic impetigo.10 Aside from use of BP as an acne treatment, other potential exposures to BP include bleached flour13 and orthopedic bone cement. Occupations at risk for potential BP exposure include dental technicians15 and those working in plastic manufacturing.

Brimonidine—Brimonidine tartrate is a selective α2-adrenergic agonist initially used to treat open-angle glaucoma and also is used as a topical treatment for rosacea. Allergic reactions to brimonidine eye drops may present with periorbital hyperpigmentation and pruritic bullous lesions.16 Case reports of topical brimonidine ACD have demonstrated mixed patch test results, with positive patch tests to Mirvaso (Galderma) as is but negative patch tests to pure brimonidine tartrate 0.33%.17,18 Ringuet and Houle19 reported the first known positive patch test reaction to pure topical brimonidine, testing with brimonidine tartrate 1% in petrolatum.20,21 Clinicians should be attuned to ACD to topical brimonidine in patients previously treated for glaucoma, as prior use of ophthalmic preparations may result in sensitization.18,20

Antimicrobials

Clindamycin—Clindamycin targets bacterial protein synthesis and is an effective adjunct in the treatment of acne. Despite its widespread and often long-term use, topical clindamycin is a weak sensitizer.22 To date, limited case reports on ACD to topical clindamycin exist.23-28 Rare clinical patterns of ACD to clindamycin include mimickers of irritant retinoid dermatitis, erythema multiforme, or pustular rosacea.25,26,29

Metronidazole—Metronidazole is a bactericidal agent that disrupts nucleic acid synthesis with additional anti-inflammatory properties used in the treatment of rosacea. Allergic contact dermatitis to topical metronidazole has been reported.30-34 In 2006, Beutner at al35 patch tested 215 patients using metronidazole gel 1%, which revealed no positive reactions to indicate contact sensitization. Similarly, Jappe et al36 found no positive reactions to metronidazole 2% in petrolatum in their prospective analysis of 78 rosacea patients, further highlighting the exceptionally low incidence of ACD. Cross-reaction with isothiazolinone, which shares structurally similar properties to metronidazole, has been speculated.31,34 One patient developed an acute reaction to metronidazole gel 0.75% within 24 hours of application, suggesting that isothiazolinone may act as a sensitizer, though this relationship has not been proven.31

Neomycin—Neomycin blocks bacterial protein synthesis and is available in both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) formulations. It commonly is used to treat and prevent superficial wound infections as an OTC antibiotic and also has otic, ophthalmologic, gastroenterologic, urologic, and peritoneal formulations. It also can be used in the dental and veterinary fields and is present in some animal feeds and in trace amounts in some vaccines for humans. Neomycin is a common antibiotic contact allergen, and the most recently reported 2017-2018 North American Contact Dermatitis Group data cycle placed it at number 12 with 5.4% positivity.37 Co-reactions with bacitracin can occur, substantially limiting OTC topical antibiotic options for allergic patients. A safe alternative for patients with neomycin (and bacitracin and polymyxin) contact allergy is prescription mupirocin.

Bacitracin—Bacitracin interferes with peptidoglycan and cell-wall synthesis to treat superficial cutaneous infections. Similar to neomycin, it also can be found in OTC antibiotic ointments as well as in antibacterial bandages. There are several case reports of patients with both type IV delayed hypersensitivity (contact dermatitis) and type I anaphylactic reactions to bacitracin38-40; patch testers should be aware of this rare association. Bacitracin was positive in 5.5% of patch tested patients in the 2017-2018 North American Contact Dermatitis Group data cycle,37 and as with neomycin, bacitracin also is commonly patch tested in most screening patch test series.

Polymyxin—Polymyxin is a polypeptide topical antibiotic that is used to treat superficial wound infections and can be used in combination with neomycin and/or bacitracin. Historically, it is a less common antibiotic allergen; however, it is now frequently included in comprehensive patch test series, as the frequency of positive reactions seems to be increasing, probably due to polysensitization with neomycin and bacitracin.

Nystatin—Nystatin is an antifungal that binds to ergosterol and disrupts the cell wall. Cases exist of ACD to topical nystatin as well as systemic ACD from oral exposure, though both are quite rare. Authors have surmised that the overall low rates of ACD may be due to poor skin absorption of nystatin, which also can confound patch testing.41,42 For patients with suspected ACD to nystatin, repeat open application testing also can be performed to confirm allergy.

Imidazole Antifungals—Similar to nystatins, imidazole antifungals also work by disrupting the fungal cell wall. Imidazole antifungal preparations that have been reported to cause ACD include clotrimazole, miconazole, econazole, and isoconazole, and although cross-reactivity patterns have been described, they are not always reproducible with patch testing.43 In one reported case, tioconazole found in an antifungal nail lacquer triggered ACD involving not only the fingers and toes but also the trunk.44 Erythema multiforme–like reactions also have been described from topical use.45 Commercial patch test preparations of the most common imidazole allergens do exist. Nonimidazole antifungals remain a safe option for allergic patients.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines, or H1-receptor antagonists, are marketed to be applied topically for relief of pruritus associated with allergic cutaneous reactions. Ironically, they are known to be potent sensitizers themselves. There are 6 main chemical classes of antihistamines: phenothiazines, ethylenediamines, ethanolamines, alkylamines, piperazines, and piperidines. Goossens and Linsen46 patch tested 12,460 patients from 1978 to 1997 and found the most positive reactions to promethazine (phenothiazine)(n=12), followed by diphenhydramine (ethanolamine)(n=8) and clemizole (benzimidazole)(n=6). The authors also noted cross-reactions between diphenhydramine derivatives and between promethazine and chlorpromazine.46

Doxepin is a tricyclic antidepressant with antihistamine activity and is a well-documented sensitizer.47-52 Taylor et al47 evaluated 97 patients with chronic dermatoses, and patch testing revealed 17 (17.5%) positive reactions to doxepin cream, 13 (76.5%) of which were positive reactions to both the commercial cream and the active ingredient. Patch testing using doxepin dilution as low as 0.5% in petrolatum is sufficient to provoke a strong (++) allergic reaction.50,51 Early-onset ACD following the use of doxepin cream suggests the possibility of prior sensitization, perhaps with a structurally similar phenothiazine drug.51 A keen suspicion for ACD in patients using doxepin cream for longer than the recommended duration can help make the diagnosis.49,52

Topical Analgesics

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs—Ketoprofen is one of the most frequent culprits of photoallergic contact dermatitis. Pruritic, papulovesicular, and bullous lesions typically develop acutely weeks after exposure. Prolonged photosensitivity is common and can last years after discontinuation of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.53 Cases of cross-reactions and co-sensitization to structurally similar substances have been reported, including to benzophenone-related chemicals in sunscreen and aldehyde groups in fragrance mix.53,54

Diclofenac gel generally is well tolerated in the topical treatment of joint pain and inflammation. In the setting of ACD, patients typically present with dermatitis localized to the area of application.55 Immediate cessation and avoidance of topical diclofenac are crucial components of management. Although systemic contact dermatitis has been reported with oral diclofenac use,56 a recent report suggested that oral diclofenac may be well tolerated for some patients with topical ACD.57

Publications on bufexamac-induced ACD mainly consist of international reports, as this medication has been discontinued in the United States. Bufexamac is a highly sensitizing agent that can lead to severe polymorphic eruptions requiring treatment with prednisolone and even hospitalization.58 In one Australian case report, a mother developed an edematous, erythematous, papulovesicular eruption on the breast while breastfeeding her baby, who was being treated with bufexamac cream 5% for infantile eczema.59 Carprofen-induced photoallergic contact dermatitis is associated with occupational exposure in pharmaceutical workers.60,61 A few case reports on other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including etofenamate and aceclofenac, have been published.62,63

Compounded Medications—Compounded topical analgesics, which help to control pain via multiple combined effects, have gained increasing popularity in the management of chronic neuropathic pain disorders. Only a few recent retrospective studies assessing the efficacy and safety of these medications have mentioned suspected allergic cutaneous reactions.62,63 In 2015, Turrentine et al64 reported a case of ACD to cyclobenzaprine in a compound containing ketamine 10%, diclofenac 5%, baclofen 2%, bupivacaine 1%, cyclobenzaprine 2%, gabapentin 6%, ibuprofen 3%, and pentoxifylline 3% in a proprietary cream base. When patients present with suspected ACD to a compounded pain medication, obtaining individual components for patch testing is key to determining the allergic ingredient(s). We suspect that we will see a rise in reports of ACD as these topical compounds become readily adopted in clinical practices.

Patch Testing for Diagnosis

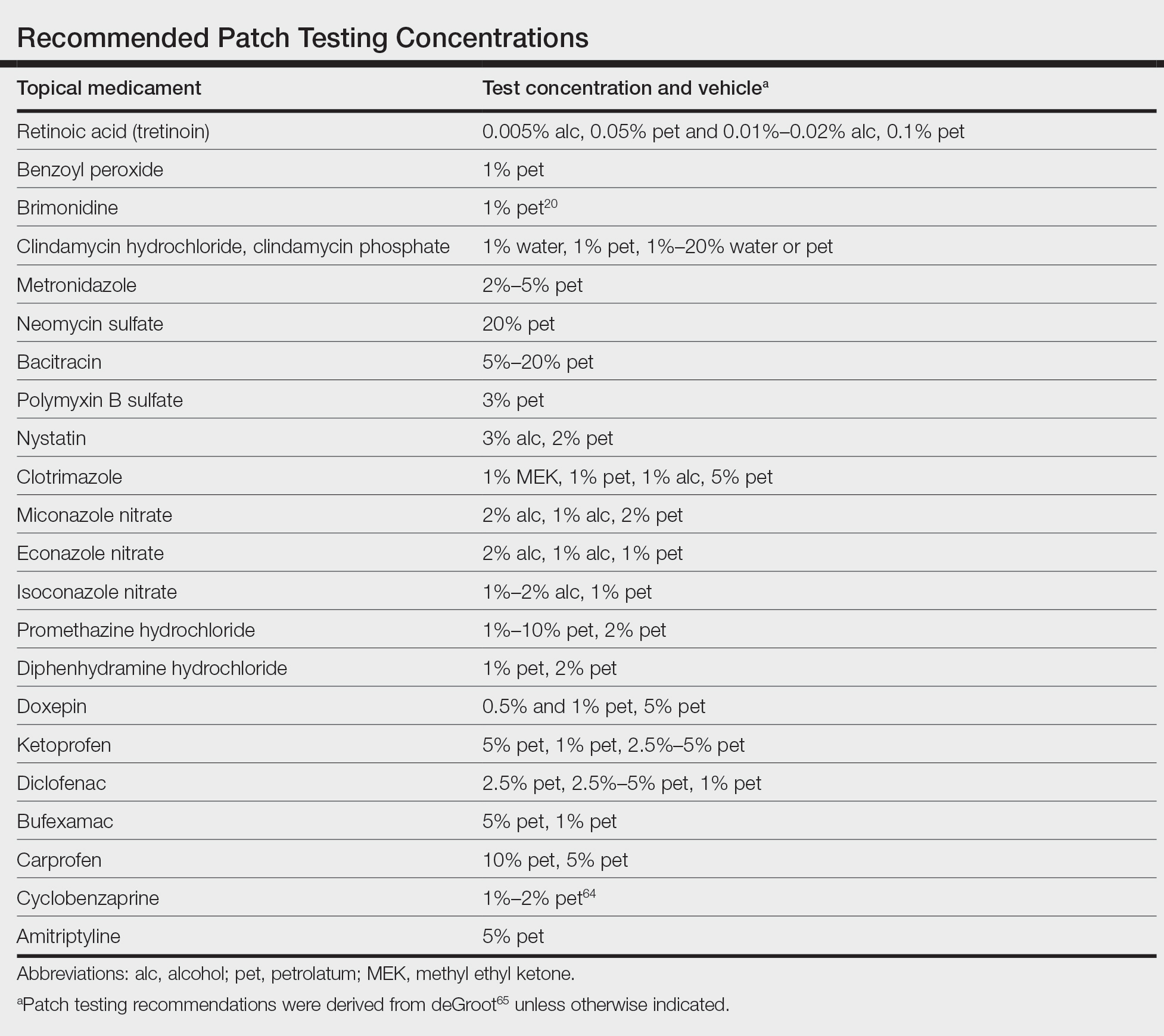

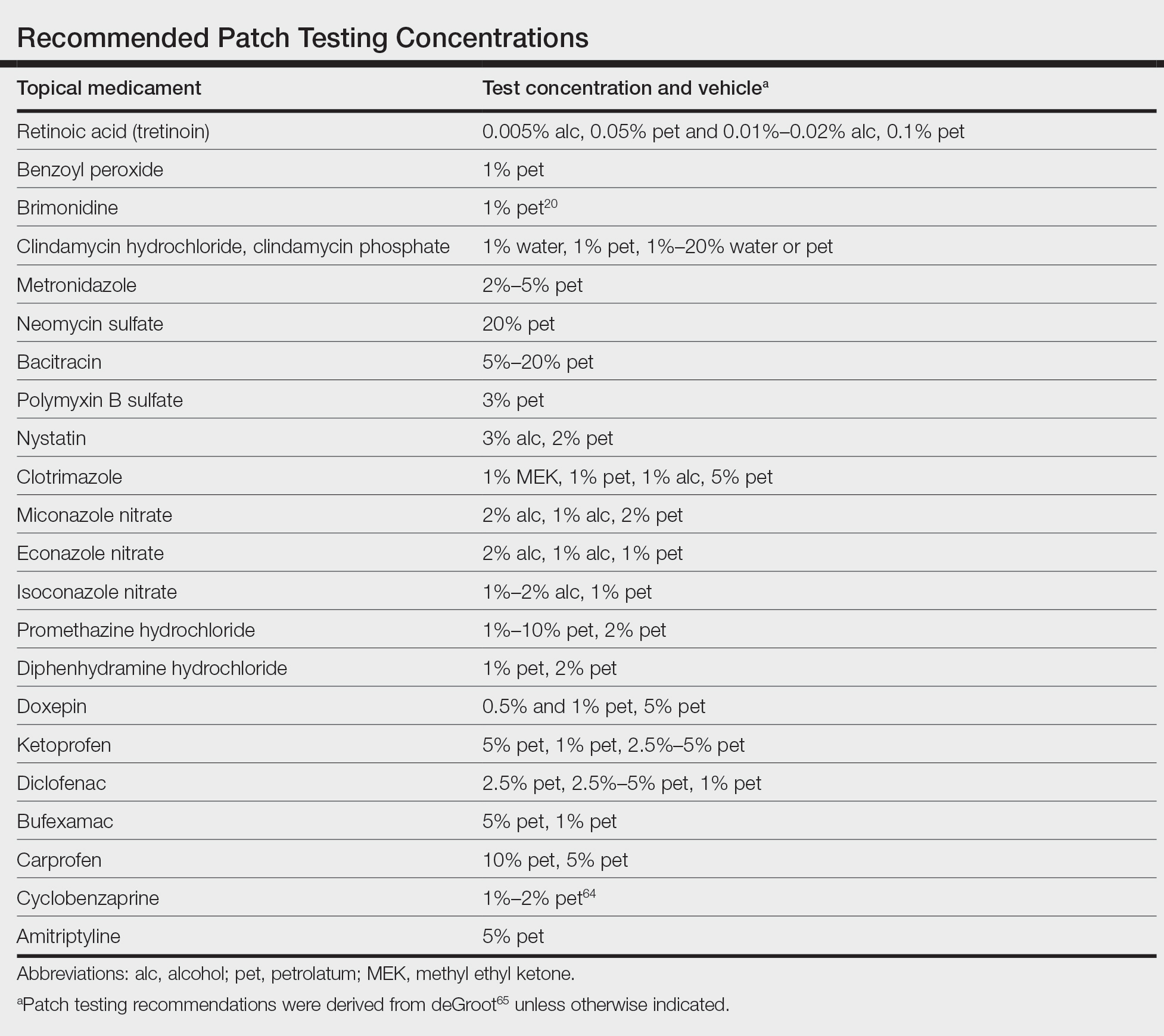

When patients present with symptoms concerning for ACD to medicaments, the astute clinician should promptly stop the suspected topical medication and consider patch testing. For common allergens such as neomycin, bacitracin, or ethylenediamine, commercial patch test preparations exist and should be used; however, for drugs that do not have a commercial patch test preparation, the patient’s product can be applied as is, keeping in mind that certain preparations (such as retinoids) can cause irritant patch test reactions, which may confound the reading. Alternatively, individual ingredients in the medication’s formulation can be requested from the manufacturer or a compounding pharmacy for targeted testing. Suggested concentrations for patch testing based on the literature and expert reference are listed in the Table. The authors (M.R., A.R.A.) frequently rely on an expert reference66 to determine ideal concentrations for patch testing. Referral to a specialized patch test clinic may be appropriate.

Final Interpretation

Although their intent is to heal, topical medicaments also can be a source of ACD. The astute clinician should consider ACD when topicals either no longer seem to help the patient or trigger new-onset dermatitis. Patch testing directly with the culprit medicament, or individual medication ingredients when needed, can lead to the diagnosis, though caution is advised. Stay tuned for part 2 of this series in which we will discuss ACD to topical steroids, immunomodulators, and anesthetic medications.

- Davis MD. Unusual patterns in contact dermatitis: medicaments. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:289-297, vi. doi:10.1016/j.det.2009.05.003

- Gilissen L, Goossens A. Frequency and trends of contact allergy to and iatrogenic contact dermatitis caused by topical drugs over a 25-year period. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:290-302. doi:10.1111/cod.12621

- Balato N, Patruno C, Lembo G, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from retinoic acid. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:51. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00846.x

- Berg JE, Bowman JP, Saenz AB. Cumulative irritation potential and contact sensitization potential of tazarotene foam 0.1% in 2 phase 1 patch studies. Cutis. 2012;90:206-211.

- Numata T, Jo R, Kobayashi Y, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by adapalene. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:187-188. doi:10.1111/cod.12410

- Anderson A, Gebauer K. Periorbital allergic contact dermatitis resulting from topical retinoic acid use. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:152-153. doi:10.1111/ajd.12041

- Blondeel A. Contact allergy to vitamin A. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:191-192. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1984.tb00976.x

- Manzano D, Aguirre A, Gardeazabal J, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from tocopheryl acetate (vitamin E) and retinol palmitate (vitamin A) in a moisturizing cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:324. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb02030.x

- Heidenheim M, Jemec GB. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from vitamin A acetate. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:439. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb02091.x

- Kim C, Craiglow BG, Watsky KL, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to benzoyl peroxide resembling impetigo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:E161-E162. doi:10.1111/pde.12585

- Sandre M, Skotnicki-Grant S. A case of a paediatric patient with allergic contact dermatitis to benzoyl peroxide. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:226-228. doi:10.1177/1203475417733462

- Corazza M, Amendolagine G, Musmeci D, et al. Sometimes even Dr Google is wrong: an unusual contact dermatitis caused by benzoyl peroxide. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:380-381. doi:10.1111/cod.13086

- Adelman M, Mohammad T, Kerr H. Allergic contact dermatitis due to benzoyl peroxide from an unlikely source. Dermatitis. 2019;30:230-231. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000470

- Gatica-Ortega ME, Pastor-Nieto MA. Allergic contact dermatitis to Glycyrrhiza inflata root extract in an anti-acne cosmetic product [published online April 28, 2021]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.13872

- Ockenfels HM, Uter W, Lessmann H, et al. Patch testing with benzoyl peroxide: reaction profile and interpretation of positive patch test reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:209-216. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01603.x

- Sodhi PK, Verma L, Ratan J. Dermatological side effects of brimonidine: a report of three cases. J Dermatol. 2003;30:697-700. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00461.x

- Swanson LA, Warshaw EM. Allergic contact dermatitis to topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.33% for treatment of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:832-833. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.073

- Bangsgaard N, Fischer LA, Zachariae C. Sensitization to and allergic contact dermatitis caused by Mirvaso(®)(brimonidine tartrate) for treatment of rosacea—2 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74:378-379. doi:10.1111/cod.12547

- Ringuet J, Houle MC. Case report: allergic contact dermatitis to topical brimonidine demonstrated with patch testing: insights on evaluation of brimonidine sensitization. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:636-638. doi:10.1177/1203475418789020

- Cookson H, McFadden J, White J, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by Mirvaso®, brimonidine tartrate gel 0.33%, a new topical treatment for rosaceal erythema. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:366-367. doi:10.1111/cod.12476

- Rajagopalan A, Rajagopalan B. Allergic contact dermatitis to topical brimonidine. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12299

- Veraldi S, Brena M, Barbareschi M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical antiacne drugs. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8:377-381. doi:10.1586/17512433.2015.1046839

- Vejlstrup E, Menné T. Contact dermatitis from clindamycin. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:110. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00759.x

- García R, Galindo PA, Feo F, et al. Delayed allergic reactions to amoxycillin and clindamycin. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:116-117. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02312.x

- Muñoz D, Del Pozo MD, Audicana M, et al. Erythema-multiforme-like eruption from antibiotics of 3 different groups. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:227-228. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02187.x

- Romita P, Ettorre G, Corazza M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by clindamycin mimicking ‘retinoid flare.’ Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:181-182. doi:10.1111/cod.12784