User login

Deprescribing in older adults: An overview

Mr. J, age 73, has a 25-year history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. His medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, insomnia, and allergic rhinitis. His last laboratory test results indicate his hemoglobin A1c, thyroid-stimulating hormone, low-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure measurements are at goal. He believes his conditions are well controlled but cites concerns about taking multiple medications each day and being able to afford his medications.

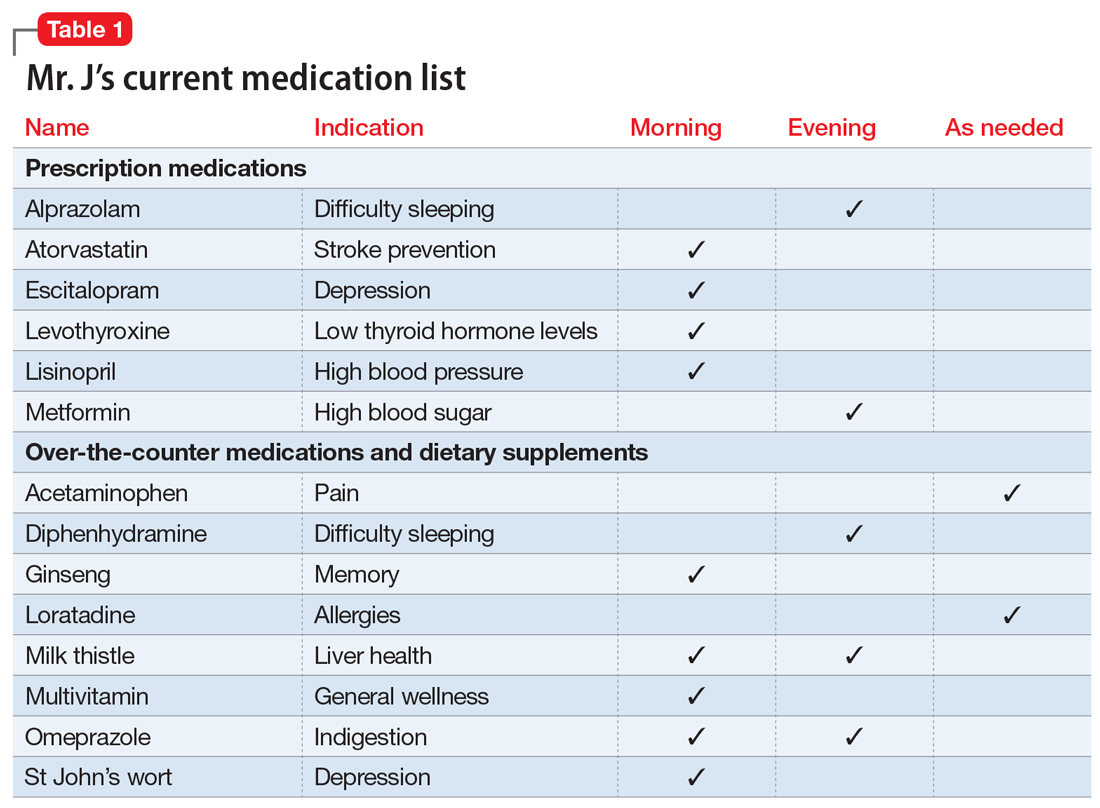

You review the list of Mr. J’s current prescription medications, which include alprazolam 0.5 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, escitalopram 10 mg/d, levothyroxine 0.125 mg/d, lisinopril 20 mg/d, and metformin XR 1,000 mg/d. Mr. J reports taking over-the-counter (OTC) acetaminophen as needed for pain, diphenhydramine for insomnia, loratadine as needed for allergic rhinitis, and omeprazole for 2 years for indigestion. After further questioning, he also reports taking ginseng, milk thistle, a multivitamin, and, based on a friend’s recommendation, St John’s Wort (Table 1).

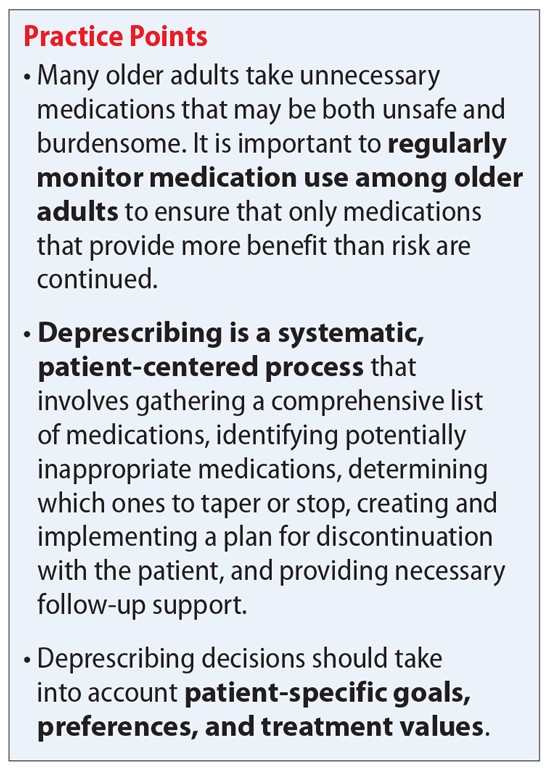

Similar to Mr. J, many older adults take multiple medications to manage chronic health conditions and promote their overall health. On average, 30% of older adults take ≥5 medications.1 Among commonly prescribed medications for these patients, an estimated 1 in 5 of may be inappropriate.1 Older adults have high rates of polypharmacy (often defined as taking ≥5 medications1), age-related physiological changes, increased number of comorbidities, and frailty, all of which can increase the risk of medication-related adverse events.2 As a result, older patients’ medications should be regularly evaluated to determine if each medication is appropriate to continue or should be tapered or stopped.

Deprescribing, in which medications are tapered or discontinued using a patient-centered approach, should be considered when a patient is no longer receiving benefit from a medication, or when the harm may exceed the benefit.1,3

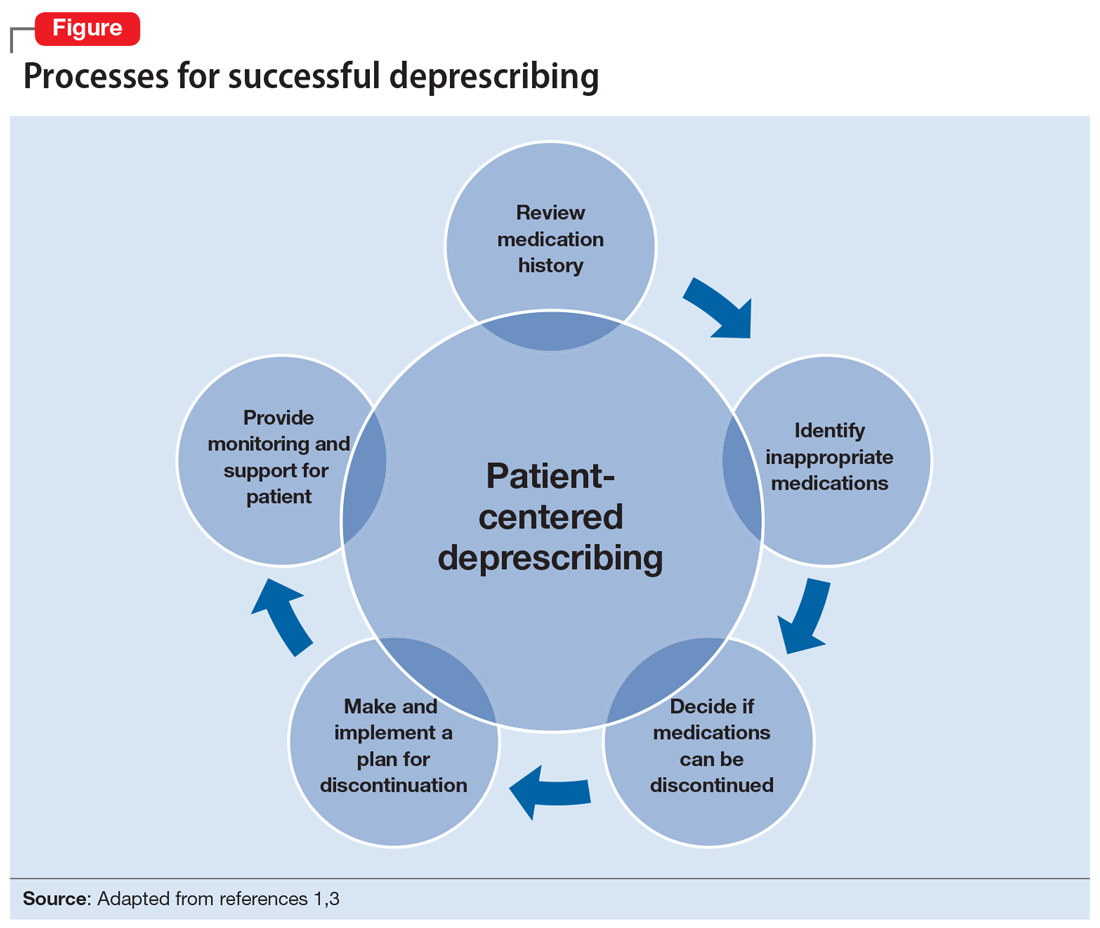

Several researchers1,3 and organizations have published detailed descriptions of and guidelines for the process of deprescribing (see Related Resources). Here we provide a brief overview of this process (Figure1,3). The first step is to assemble a list of all prescription and OTC medications, herbal products, vitamins, or nutritional supplements the patient is taking. It is important to specifically ask patients about their use of nonprescription products, because these products are infrequently documented in medical records.

The second step is to evaluate the indication, effectiveness, safety, and patient’s adherence to each medication while beginning to consider opportunities to limit treatment burden and the risk of harm from medications. Ideally, this assessment should involve a patient-centered conversation that considers the patient’s goals, preferences, and treatment values. Many resources can be used to evaluate which medications might be inappropriate for an older adult. Two examples are the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria5 and STOPP/START criteria.6 By looking at these resources, you could identify that (for example) anticholinergic medications should be avoided in older patients due to an increased risk of adverse effects, change in cognitive status, and falls.5,6 These resources can aid in identifying, prioritizing, and deprescribing potentially harmful and/or inappropriate medications.

The next step is to decide whether any medications should be discontinued. Whenever possible, include the patient in this conversation, as they may have strong feelings about their current medication regimen. When there are multiple medications that can be discontinued, consider which medication to stop first based on potential harm, patient resistance, and other factors.

Continue to: Subsequently, work with...

Subsequently, work with the patient to create a plan for stopping or lowering the dose or frequency of the medication. These changes should be individualized based on the patient’s preferences as well as the properties of the medication. For example, some medications can be immediately discontinued, while others (eg, benzodiazepines) may need to be slowly tapered. It is important to consider if the patient will need to switch to a safer medication, change their behaviors (eg, lifestyle changes), or engage in alternative treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia) when they stop their current medication. Take an active role in monitoring your patient during this process, and encourage them to reach out to you or to their primary clinician if they have concerns.

CASE CONTINUED

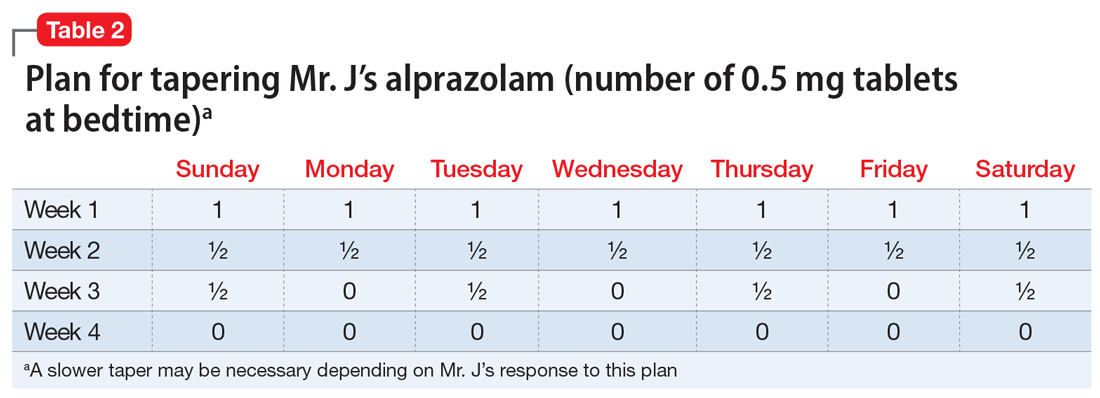

Mr. J is a candidate for deprescribing because he has expressed concerns about his current regimen, and because he is taking potentially unsafe medications. The 2 medications he’s taking that may cause the most harm are diphenhydramine and alprazolam, due to the risk of cognitive impairment and falls. Through a patient-centered conversation, Mr. J says he is willing to stop diphenhydramine immediately and taper off the alprazolam over the next month, with the support of a tapering chart (Table 2). You explain to him that a long tapering of alprazolam may be necessary. He is willing to try good sleep hygiene practices and will put off starting trazodone as an alternative to diphenhydramine until he sees if it will be necessary. You make a note to follow up with him in 1 week to assess his insomnia and adherence to the new treatment plan. You also teach Mr. J that some of his supplements may interact with his prescription medications, such as St John’s Wort with escitalopram (ie, risk of serotonin syndrome) and ginseng with metformin (ie, risk for hypoglycemia). He says he doesn’t take ginseng, milk thistle, or St John’s Wort regularly, and because he feels they do not offer any benefit, he will stop taking them. He says that at his next visit with his primary care physician, he will bring up the idea of stopping omeprazole.

Related Resources

- Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing guidelines and algorithms. https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-guidelines-algorithms/

- US Deprescribing Research Network. Resources for Clinicians. https://deprescribingresearch.org/resources-2/resources-for-clinicians/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Zestril

Metformin XR • Glucophage XR

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

2. Gibson G, Kennedy LH, Barlow G. Polypharmacy in older adults. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):40-46.

3. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmcol. 2014;78(4):738-747.

4. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1021-1031.

5. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.

Mr. J, age 73, has a 25-year history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. His medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, insomnia, and allergic rhinitis. His last laboratory test results indicate his hemoglobin A1c, thyroid-stimulating hormone, low-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure measurements are at goal. He believes his conditions are well controlled but cites concerns about taking multiple medications each day and being able to afford his medications.

You review the list of Mr. J’s current prescription medications, which include alprazolam 0.5 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, escitalopram 10 mg/d, levothyroxine 0.125 mg/d, lisinopril 20 mg/d, and metformin XR 1,000 mg/d. Mr. J reports taking over-the-counter (OTC) acetaminophen as needed for pain, diphenhydramine for insomnia, loratadine as needed for allergic rhinitis, and omeprazole for 2 years for indigestion. After further questioning, he also reports taking ginseng, milk thistle, a multivitamin, and, based on a friend’s recommendation, St John’s Wort (Table 1).

Similar to Mr. J, many older adults take multiple medications to manage chronic health conditions and promote their overall health. On average, 30% of older adults take ≥5 medications.1 Among commonly prescribed medications for these patients, an estimated 1 in 5 of may be inappropriate.1 Older adults have high rates of polypharmacy (often defined as taking ≥5 medications1), age-related physiological changes, increased number of comorbidities, and frailty, all of which can increase the risk of medication-related adverse events.2 As a result, older patients’ medications should be regularly evaluated to determine if each medication is appropriate to continue or should be tapered or stopped.

Deprescribing, in which medications are tapered or discontinued using a patient-centered approach, should be considered when a patient is no longer receiving benefit from a medication, or when the harm may exceed the benefit.1,3

Several researchers1,3 and organizations have published detailed descriptions of and guidelines for the process of deprescribing (see Related Resources). Here we provide a brief overview of this process (Figure1,3). The first step is to assemble a list of all prescription and OTC medications, herbal products, vitamins, or nutritional supplements the patient is taking. It is important to specifically ask patients about their use of nonprescription products, because these products are infrequently documented in medical records.

The second step is to evaluate the indication, effectiveness, safety, and patient’s adherence to each medication while beginning to consider opportunities to limit treatment burden and the risk of harm from medications. Ideally, this assessment should involve a patient-centered conversation that considers the patient’s goals, preferences, and treatment values. Many resources can be used to evaluate which medications might be inappropriate for an older adult. Two examples are the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria5 and STOPP/START criteria.6 By looking at these resources, you could identify that (for example) anticholinergic medications should be avoided in older patients due to an increased risk of adverse effects, change in cognitive status, and falls.5,6 These resources can aid in identifying, prioritizing, and deprescribing potentially harmful and/or inappropriate medications.

The next step is to decide whether any medications should be discontinued. Whenever possible, include the patient in this conversation, as they may have strong feelings about their current medication regimen. When there are multiple medications that can be discontinued, consider which medication to stop first based on potential harm, patient resistance, and other factors.

Continue to: Subsequently, work with...

Subsequently, work with the patient to create a plan for stopping or lowering the dose or frequency of the medication. These changes should be individualized based on the patient’s preferences as well as the properties of the medication. For example, some medications can be immediately discontinued, while others (eg, benzodiazepines) may need to be slowly tapered. It is important to consider if the patient will need to switch to a safer medication, change their behaviors (eg, lifestyle changes), or engage in alternative treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia) when they stop their current medication. Take an active role in monitoring your patient during this process, and encourage them to reach out to you or to their primary clinician if they have concerns.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J is a candidate for deprescribing because he has expressed concerns about his current regimen, and because he is taking potentially unsafe medications. The 2 medications he’s taking that may cause the most harm are diphenhydramine and alprazolam, due to the risk of cognitive impairment and falls. Through a patient-centered conversation, Mr. J says he is willing to stop diphenhydramine immediately and taper off the alprazolam over the next month, with the support of a tapering chart (Table 2). You explain to him that a long tapering of alprazolam may be necessary. He is willing to try good sleep hygiene practices and will put off starting trazodone as an alternative to diphenhydramine until he sees if it will be necessary. You make a note to follow up with him in 1 week to assess his insomnia and adherence to the new treatment plan. You also teach Mr. J that some of his supplements may interact with his prescription medications, such as St John’s Wort with escitalopram (ie, risk of serotonin syndrome) and ginseng with metformin (ie, risk for hypoglycemia). He says he doesn’t take ginseng, milk thistle, or St John’s Wort regularly, and because he feels they do not offer any benefit, he will stop taking them. He says that at his next visit with his primary care physician, he will bring up the idea of stopping omeprazole.

Related Resources

- Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing guidelines and algorithms. https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-guidelines-algorithms/

- US Deprescribing Research Network. Resources for Clinicians. https://deprescribingresearch.org/resources-2/resources-for-clinicians/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Zestril

Metformin XR • Glucophage XR

Trazodone • Desyrel

Mr. J, age 73, has a 25-year history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. His medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, insomnia, and allergic rhinitis. His last laboratory test results indicate his hemoglobin A1c, thyroid-stimulating hormone, low-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure measurements are at goal. He believes his conditions are well controlled but cites concerns about taking multiple medications each day and being able to afford his medications.

You review the list of Mr. J’s current prescription medications, which include alprazolam 0.5 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, escitalopram 10 mg/d, levothyroxine 0.125 mg/d, lisinopril 20 mg/d, and metformin XR 1,000 mg/d. Mr. J reports taking over-the-counter (OTC) acetaminophen as needed for pain, diphenhydramine for insomnia, loratadine as needed for allergic rhinitis, and omeprazole for 2 years for indigestion. After further questioning, he also reports taking ginseng, milk thistle, a multivitamin, and, based on a friend’s recommendation, St John’s Wort (Table 1).

Similar to Mr. J, many older adults take multiple medications to manage chronic health conditions and promote their overall health. On average, 30% of older adults take ≥5 medications.1 Among commonly prescribed medications for these patients, an estimated 1 in 5 of may be inappropriate.1 Older adults have high rates of polypharmacy (often defined as taking ≥5 medications1), age-related physiological changes, increased number of comorbidities, and frailty, all of which can increase the risk of medication-related adverse events.2 As a result, older patients’ medications should be regularly evaluated to determine if each medication is appropriate to continue or should be tapered or stopped.

Deprescribing, in which medications are tapered or discontinued using a patient-centered approach, should be considered when a patient is no longer receiving benefit from a medication, or when the harm may exceed the benefit.1,3

Several researchers1,3 and organizations have published detailed descriptions of and guidelines for the process of deprescribing (see Related Resources). Here we provide a brief overview of this process (Figure1,3). The first step is to assemble a list of all prescription and OTC medications, herbal products, vitamins, or nutritional supplements the patient is taking. It is important to specifically ask patients about their use of nonprescription products, because these products are infrequently documented in medical records.

The second step is to evaluate the indication, effectiveness, safety, and patient’s adherence to each medication while beginning to consider opportunities to limit treatment burden and the risk of harm from medications. Ideally, this assessment should involve a patient-centered conversation that considers the patient’s goals, preferences, and treatment values. Many resources can be used to evaluate which medications might be inappropriate for an older adult. Two examples are the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria5 and STOPP/START criteria.6 By looking at these resources, you could identify that (for example) anticholinergic medications should be avoided in older patients due to an increased risk of adverse effects, change in cognitive status, and falls.5,6 These resources can aid in identifying, prioritizing, and deprescribing potentially harmful and/or inappropriate medications.

The next step is to decide whether any medications should be discontinued. Whenever possible, include the patient in this conversation, as they may have strong feelings about their current medication regimen. When there are multiple medications that can be discontinued, consider which medication to stop first based on potential harm, patient resistance, and other factors.

Continue to: Subsequently, work with...

Subsequently, work with the patient to create a plan for stopping or lowering the dose or frequency of the medication. These changes should be individualized based on the patient’s preferences as well as the properties of the medication. For example, some medications can be immediately discontinued, while others (eg, benzodiazepines) may need to be slowly tapered. It is important to consider if the patient will need to switch to a safer medication, change their behaviors (eg, lifestyle changes), or engage in alternative treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia) when they stop their current medication. Take an active role in monitoring your patient during this process, and encourage them to reach out to you or to their primary clinician if they have concerns.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. J is a candidate for deprescribing because he has expressed concerns about his current regimen, and because he is taking potentially unsafe medications. The 2 medications he’s taking that may cause the most harm are diphenhydramine and alprazolam, due to the risk of cognitive impairment and falls. Through a patient-centered conversation, Mr. J says he is willing to stop diphenhydramine immediately and taper off the alprazolam over the next month, with the support of a tapering chart (Table 2). You explain to him that a long tapering of alprazolam may be necessary. He is willing to try good sleep hygiene practices and will put off starting trazodone as an alternative to diphenhydramine until he sees if it will be necessary. You make a note to follow up with him in 1 week to assess his insomnia and adherence to the new treatment plan. You also teach Mr. J that some of his supplements may interact with his prescription medications, such as St John’s Wort with escitalopram (ie, risk of serotonin syndrome) and ginseng with metformin (ie, risk for hypoglycemia). He says he doesn’t take ginseng, milk thistle, or St John’s Wort regularly, and because he feels they do not offer any benefit, he will stop taking them. He says that at his next visit with his primary care physician, he will bring up the idea of stopping omeprazole.

Related Resources

- Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing guidelines and algorithms. https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-guidelines-algorithms/

- US Deprescribing Research Network. Resources for Clinicians. https://deprescribingresearch.org/resources-2/resources-for-clinicians/

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Zestril

Metformin XR • Glucophage XR

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

2. Gibson G, Kennedy LH, Barlow G. Polypharmacy in older adults. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):40-46.

3. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmcol. 2014;78(4):738-747.

4. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1021-1031.

5. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.

1. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

2. Gibson G, Kennedy LH, Barlow G. Polypharmacy in older adults. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):40-46.

3. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmcol. 2014;78(4):738-747.

4. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1021-1031.

5. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.