User login

Hypopigmented Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in a Hispanic Infant

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

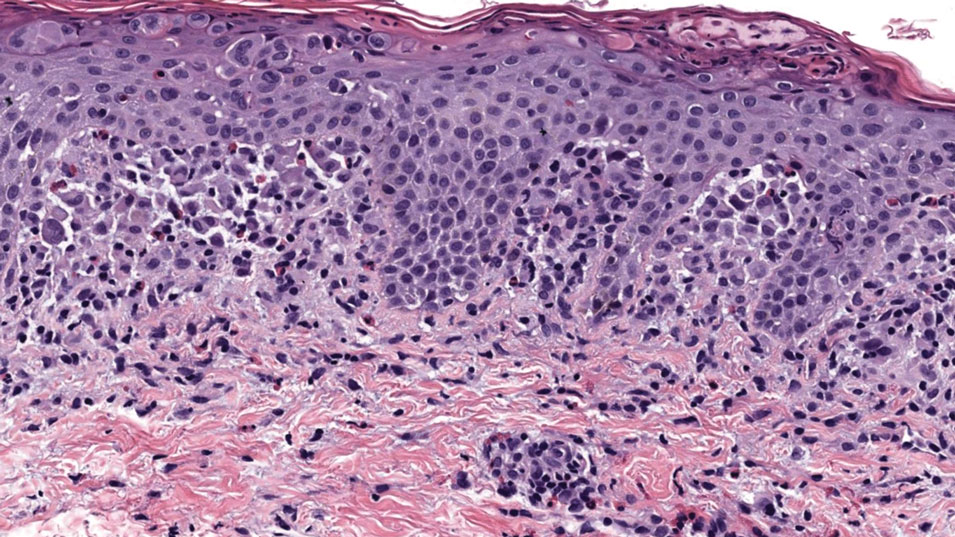

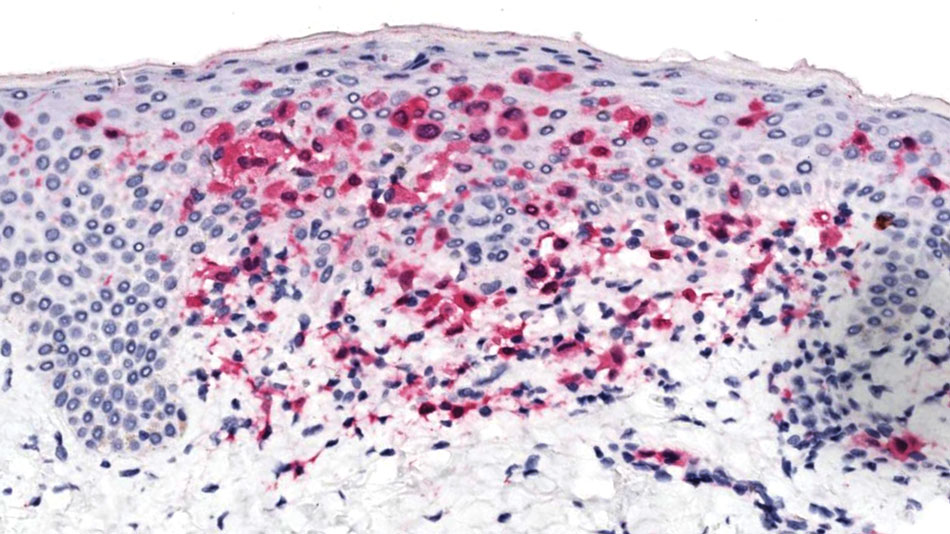

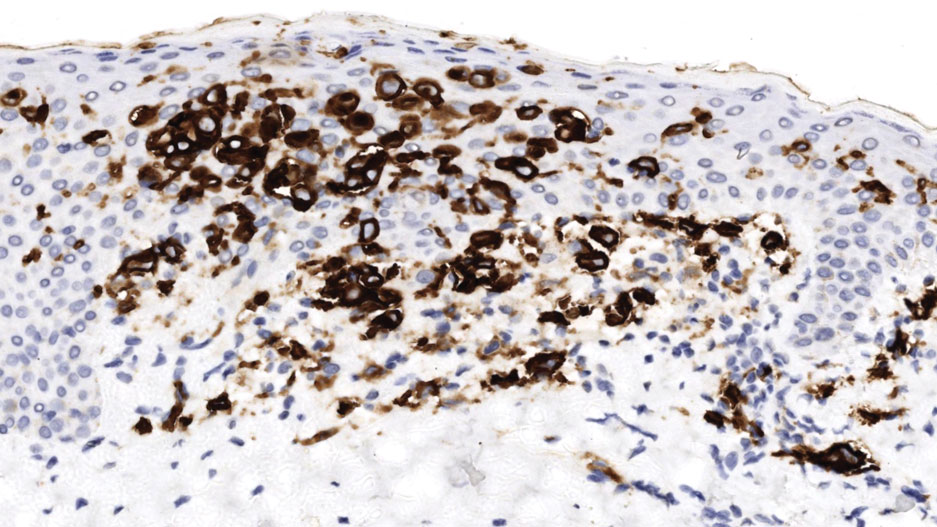

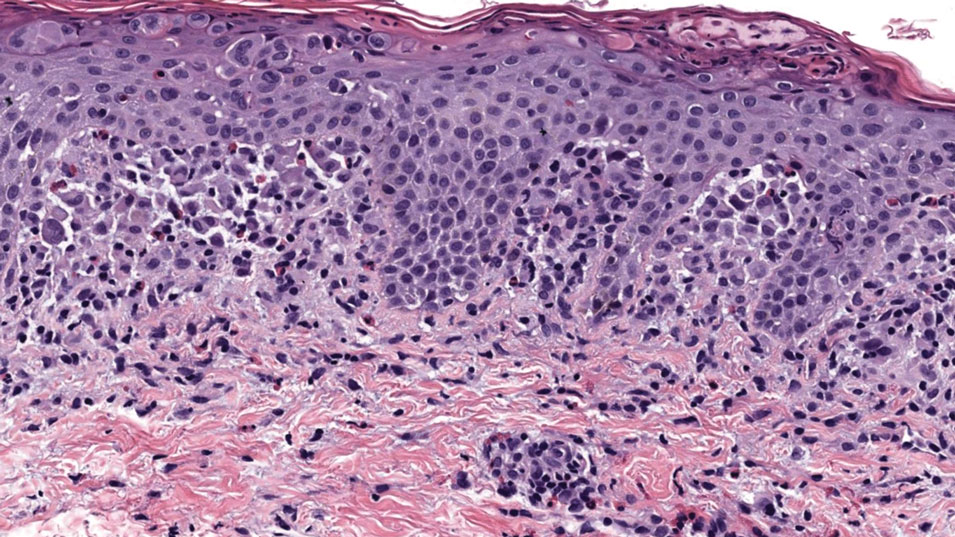

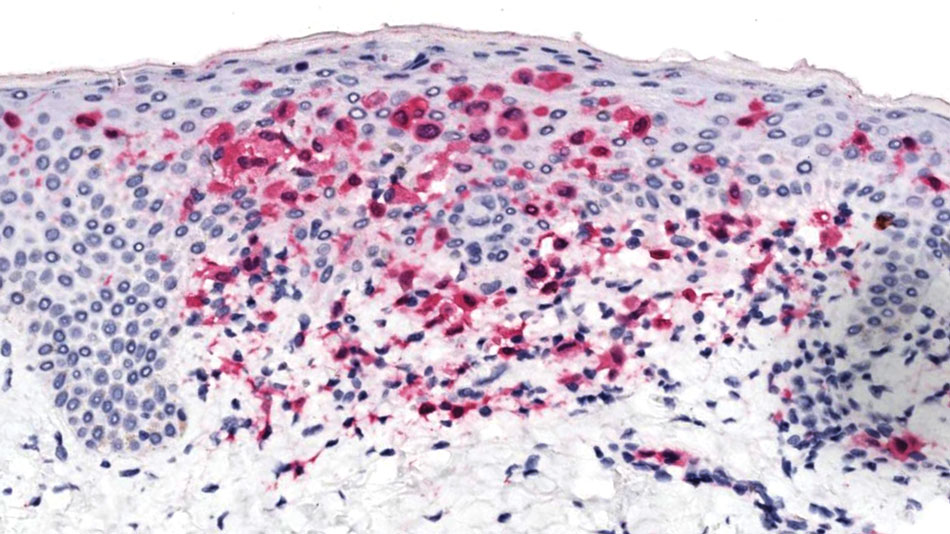

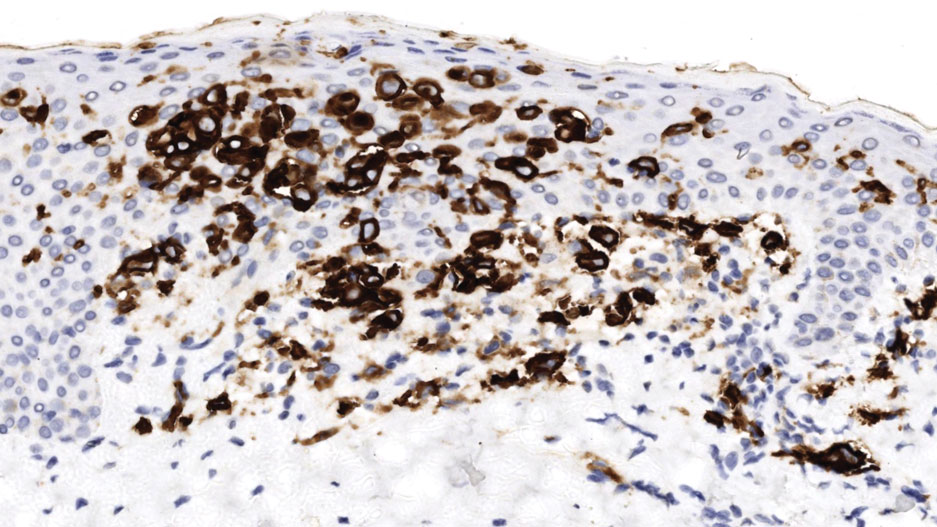

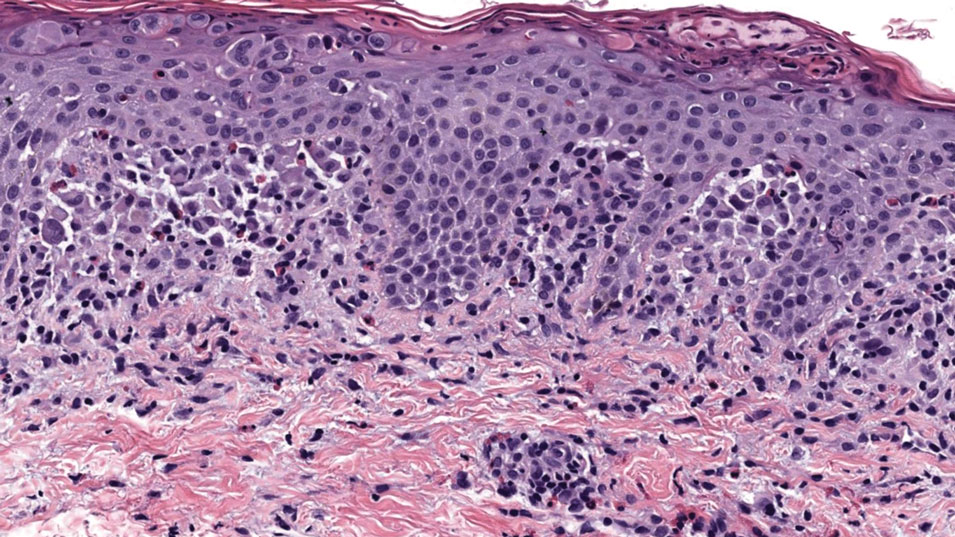

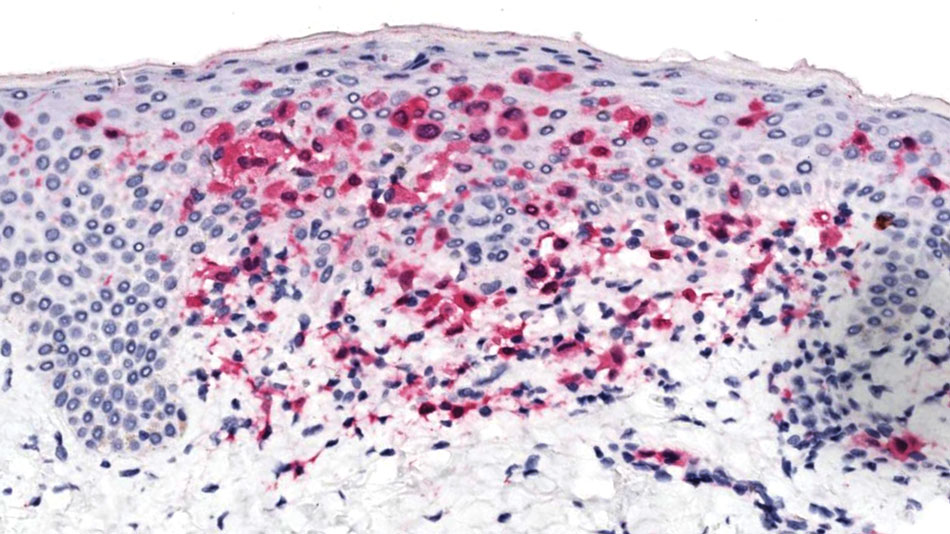

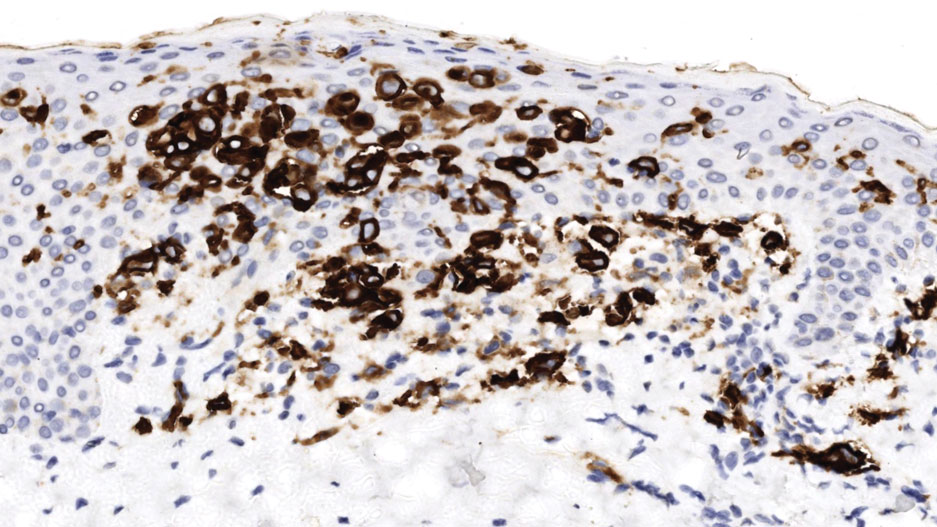

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

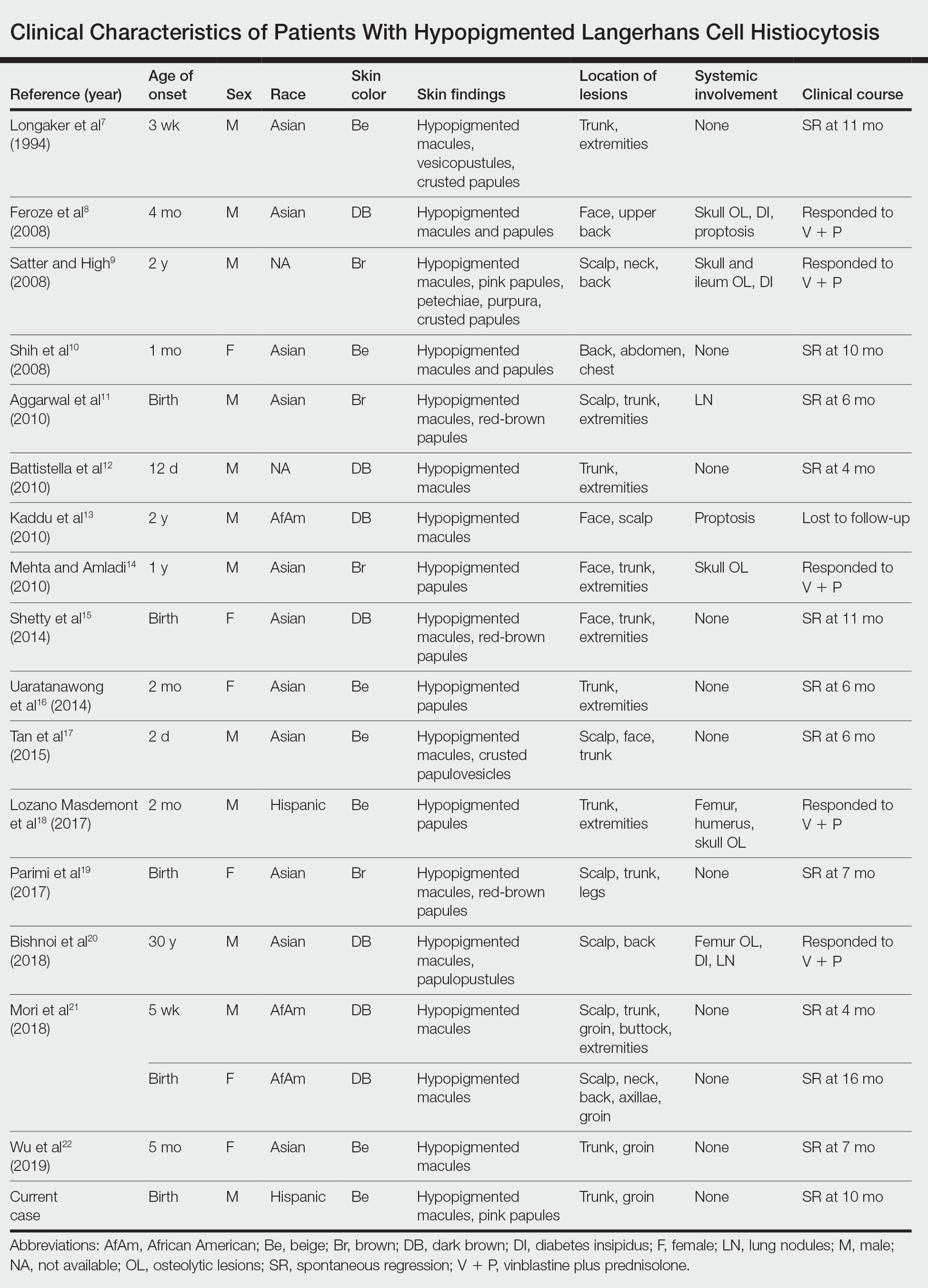

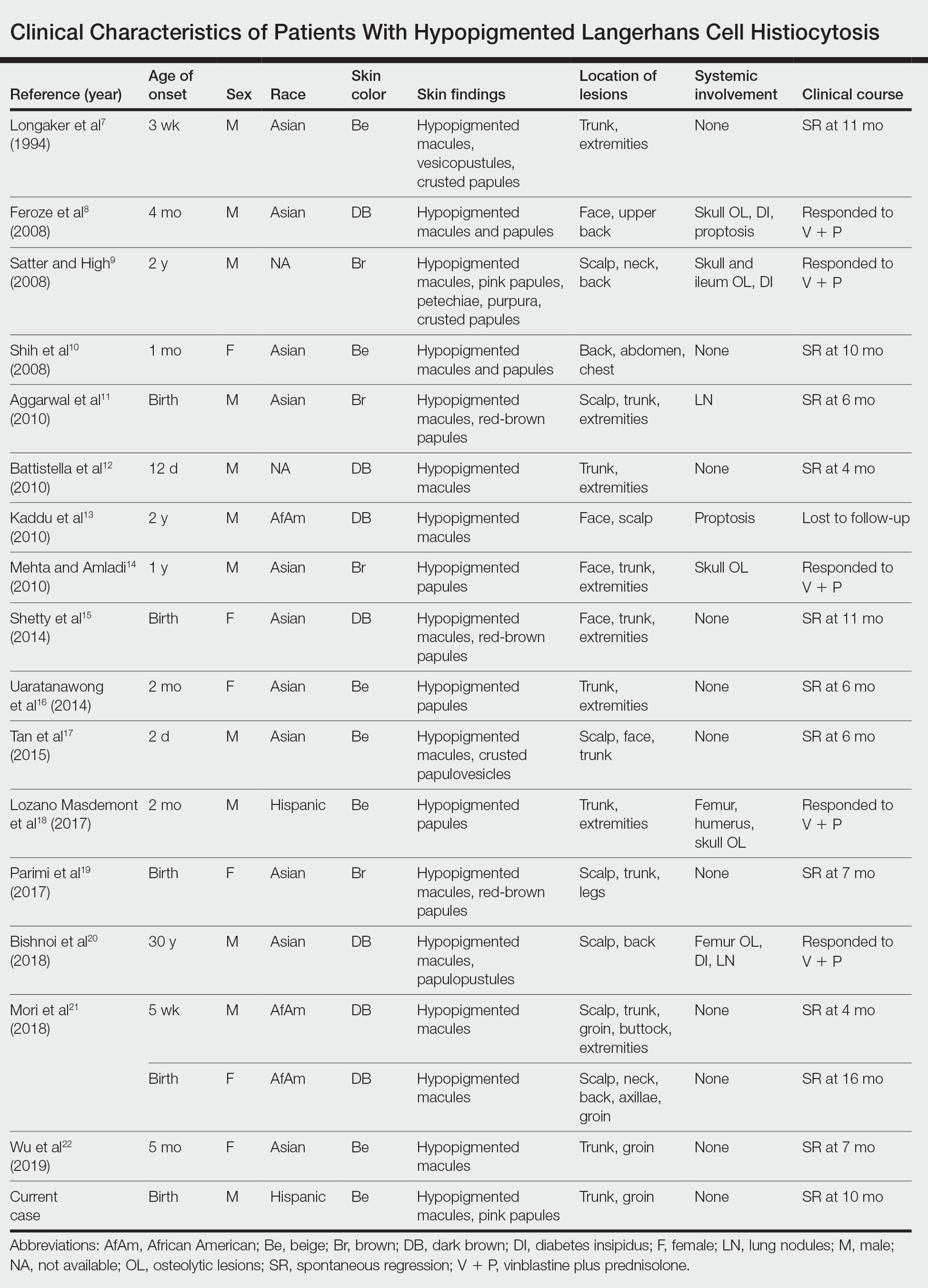

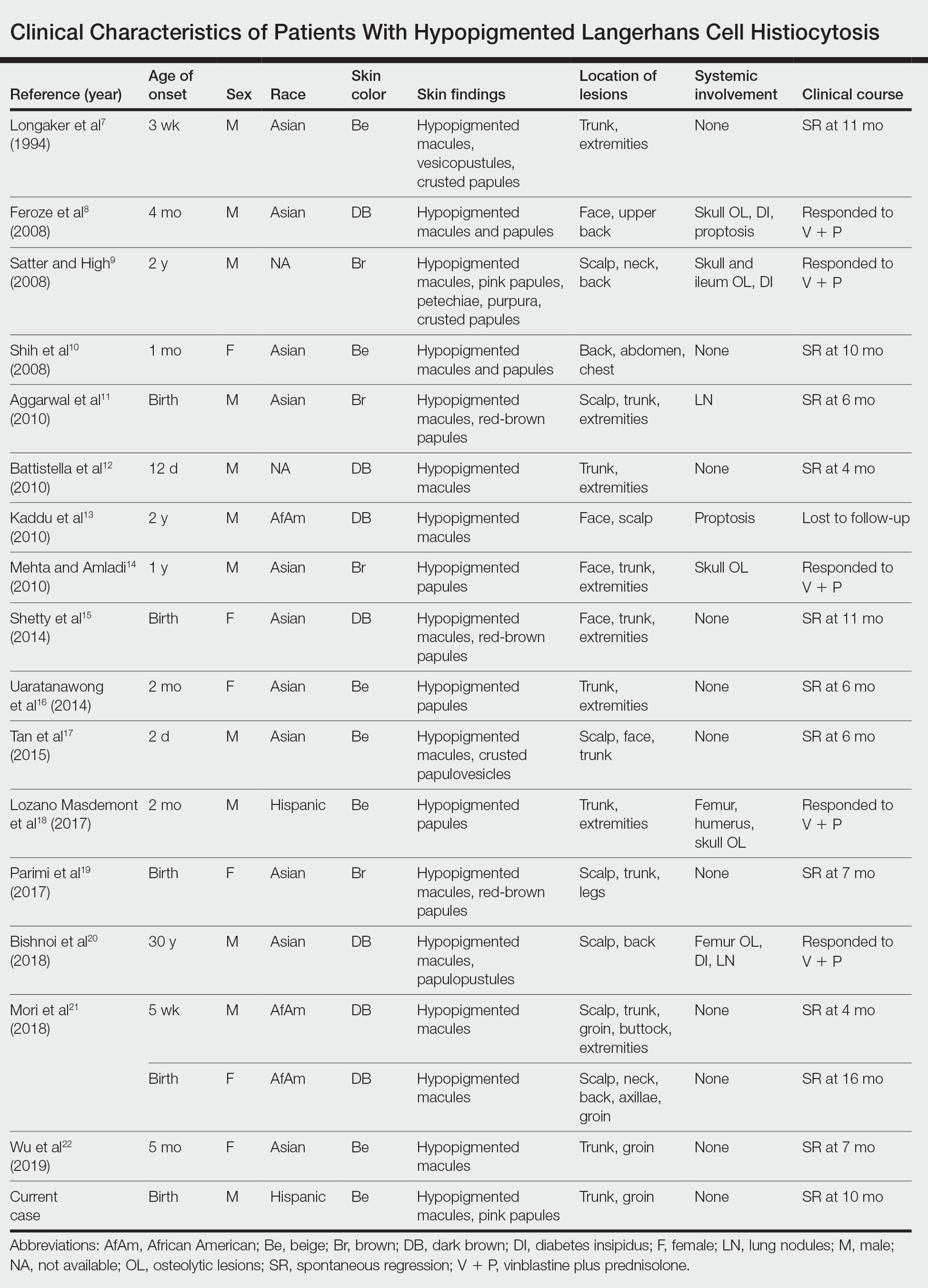

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

To the Editor:

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare inflammatory neoplasia caused by accumulation of clonal Langerhans cells in 1 or more organs. The clinical spectrum is diverse, ranging from mild, single-organ involvement that may resolve spontaneously to severe progressive multisystem disease that can be fatal. It is most prevalent in children, affecting an estimated 4 to 5 children for every 1 million annually, with male predominance.1 The pathogenesis is driven by activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, with the BRAF V600E mutation detected in most LCH patients, resulting in proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells and dysregulated expression of inflammatory cytokines in LCH lesions.2 A biopsy of lesional tissue is required for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei that are positive for CD1a and CD207 proteins on immunohistochemical staining.3

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized by the extent of organ involvement. It commonly affects the bones, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.4 Single-system LCH involves a single organ with unifocal or multifocal lesions; multisystem LCH involves 2 or more organs and has a worse prognosis if risk organs (eg, liver, spleen, bone marrow) are involved.4

Skin lesions are reported in more than half of LCH cases and are the most common initial manifestation in patients younger than 2 years.4 Cutaneous findings are highly variable, which poses a diagnostic challenge. Common morphologies include erythematous papules, pustules, papulovesicles, scaly plaques, erosions, and petechiae. Lesions can be solitary or widespread and favor the trunk, head, and face.4 We describe an atypical case of hypopigmented cutaneous LCH and review the literature on this morphology in patients with skin of color.

A 7-month-old Hispanic male infant who was otherwise healthy presented with numerous hypopigmented macules and pink papules on the trunk and groin that had progressed since birth. A review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed 1- to 3-mm, discrete, hypopigmented macules intermixed with 1- to 2-mm pearly pink papules scattered on the back, chest, abdomen, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). Some lesions appeared koebnerized; however, the parents denied a history of scratching or trauma.

Histopathology of a lesion in the inguinal fold showed aggregates of mononuclear cells with reniform nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm in the papillary dermis, with focal extension into the epidermis. Scattered eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells were present in the dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein (Figure 4). Although epidermal Langerhans cell collections also can be seen in allergic contact dermatitis,5 predominant involvement of the papillary dermis and the presence of multinucleated giant cells are characteristic of LCH.4 Given these findings, which were consistent with LCH, the dermatopathology deemed BRAF V600E immunostaining unnecessary for diagnostic purposes.

The patient was referred to the hematology and oncology department to undergo thorough evaluation for extracutaneous involvement. The workup included a complete blood cell count, liver function testing, electrolyte assessment, skeletal survey, chest radiography, and ultrasonography of the liver and spleen. All results were negative, suggesting a diagnosis of single-system cutaneous LCH.

Three months later, the patient presented to dermatology with spontaneous regression of all skin lesions. Continued follow-up—every 6 months for 5 years—was recommended to monitor for disease recurrence or progression to multisystem disease.

Cutaneous LCH is a clinically heterogeneous disease with the potential for multisystem involvement and long-term sequelae; therefore, timely diagnosis is paramount to optimize outcomes. However, delayed diagnosis is common because of the spectrum of skin findings that can mimic common pediatric dermatoses, such as seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and diaper dermatitis.4 In one study, the median time from onset of skin lesions to diagnostic biopsy was longer than 3 months (maximum, 5 years).6 Our patient was referred to dermatology 7 months after onset of hypopigmented macules, a rarely reported cutaneous manifestation of LCH.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 1994 to 2019 using the terms Langerhans cell histiocytotis and hypopigmented yielded 17 cases of LCH presenting as hypopigmented skin lesions (Table).7-22 All cases occurred in patients with skin of color (ie, patients of Asian, Hispanic, or African descent). Hypopigmented macules were the only cutaneous manifestation in 10 (59%) cases. Lesions most commonly were distributed on the trunk (16/17 [94%]) and extremities (8/17 [47%]). The median age of onset was 1 month; 76% (13/17) of patients developed skin lesions before 1 year of age, indicating that this morphology may be more common in newborns. In most patients, the diagnosis was single-system cutaneous LCH; they exhibited spontaneous regression by 8 months of age on average, suggesting that this variant may be associated with a better prognosis. Mori and colleagues21 hypothesized that hypopigmented lesions may represent the resolving stage of active LCH based on histopathologic findings of dermal pallor and fibrosis in a hypopigmented LCH lesion. However, systemic involvement was reported in 7 cases of hypopigmented LCH, highlighting the importance of assessing for multisystem disease regardless of cutaneous morphology.21Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating hypopigmented skin eruptions in infants with darker skin types. Prompt diagnosis of this atypical variant requires a higher index of suspicion because of its rarity and the polymorphic nature of cutaneous LCH. This morphology may go undiagnosed in the setting of mild or spontaneously resolving disease; notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis and longitudinal surveillance are necessary given the potential for progressive systemic involvement.

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

1. Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71-75. doi:10.1002/pbc.21498

2. Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116:1919-1923. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-04-279083

3. Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al; Euro Histio Network. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work‐up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

4. Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: history, classification, pathobiology, clinical manifestations, and prognosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1035-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.059

5. Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504. doi:10.1111/cup.12707

6. Simko SJ, Garmezy B, Abhyankar H, et al. Differentiating skin-limited and multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2014;165:990-996. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.063

7. Longaker MA, Frieden IJ, LeBoit PE, et al. Congenital “self-healing” Langerhans cell histiocytosis: the need for long-term follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(5, pt 2):910-916. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70258-6

8. Feroze K, Unni M, Jayasree MG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented macules. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:670-672. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.45128

9. Satter EK, High WA. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and summary of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:3.

10. Chang SL, Shih IH, Kuo TT, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented macules and papules in a neonate. Dermatologica Sinica 2008;26:80-84.

11. Aggarwal V, Seth A, Jain M, et al. Congenital Langerhans cell histiocytosis with skin and lung involvement: spontaneous regression. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:811-812.

12. Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.360

13. Kaddu S, Mulyowa G, Kovarik C. Hypopigmented scaly, scalp and facial lesions and disfiguring exopthalmus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;3:E52-E53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03336.x

14. Mehta B, Amladi S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as hypopigmented papules. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:215-217. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01104.x

15. Shetty S, Monappa V, Pai K, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: a case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:264-266.

16. Uaratanawong R, Kootiratrakarn T, Sudtikoonaseth P, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis presented with multiple hypopigmented flat-topped papules: a case report and review of literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97:993-997.

17. Tan Q, Gan LQ, Wang H. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a male neonate. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:75-77. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.148587

18. Lozano Masdemont B, Gómez‐Recuero Muñoz L, Villanueva Álvarez‐Santullano A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking lichen nitidus with bone involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:231-233. doi:10.1111/ajd.12467

19. Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175432

20. Bishnoi A, De D, Khullar G, et al. Hypopigmented and acneiform lesions: an unusual initial presentation of adult-onset multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84:621-626. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_639_17

21. Mori S, Adar T, Kazlouskaya V, et al. Cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting with hypopigmented lesions: report of two cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:502-506. doi:10.1111/pde.13509

22. Wu X, Huang J, Jiang L, et al. Congenital self‐healing reticulohistiocytosis with BRAF V600E mutation in an infant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:647-650. doi:10.1111/ced.13880

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of the hypopigmented variant of cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), which has been reported exclusively in patients with skin of color.

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of hypopigmented macules, which may be the only cutaneous manifestation or may coincide with typical lesions of LCH.

- Hypopigmented cutaneous LCH may be more common in newborns and associated with a better prognosis.

Ice Pack–Induced Perniosis: A Rare and Underrecognized Association

Perniosis, or chilblain, is characterized by localized, tender, erythematous skin lesions that occur as an abnormal reaction to exposure to cold and damp conditions. Although the lesions favor the distal extremities, perniosis may present anywhere on the body. Lesions can develop within hours to days following exposure to temperature less than 10°C or damp environments with greater than 60% humidity.1 Acute cases may lead to pruritus and tenderness, whereas chronic cases may involve lesions that blister or ulcerate and can take weeks to heal. We report an unusual case of erythematous plaques arising on the buttocks of a 73-year-old woman using ice pack treatments for chronic low back pain.

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman presented with recurrent tender lesions on the buttocks of 5 years’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, and lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous plaques with areas of erosions on the left buttock with some involvement of the right buttock (Figure 1).

After a trial of oral valacyclovir for presumed herpes simplex infection provided no relief, a punch biopsy of the left buttock was performed, which revealed a cell-poor interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 2). Perieccrine lymphocytes were present in a small portion of the reticular dermis (Figure 3). The patient revealed she had been sitting on ice packs for several hours daily since the lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior to alleviate chronic low back pain.

Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, a diagnosis of perniosis secondary to ice pack therapy was made. An evaluation for concomitant or underlying connective tissue disease (CTD) including a complete blood cell count with sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), serum protein electrophoresis, and serum levels of cryoglobulins and complement components was unremarkable. Our patient was treated with simple analgesia and was encouraged to avoid direct contact with ice packs for extended periods of time. Because of her low back pain, she continued to use ice packs but readjusted them sporadically and decreased frequency of use. She had complete resolution of the lesions at 6-month follow-up.

Comment

Perniosis is a self-limited condition, manifesting as erythematous plaques or nodules following exposure to cold and damp conditions. It was first reported in 1902 by Hochsinger2 as tender submental plaques occurring in children after exposure to cold weather. Since then, reports of perniosis have been described in equestrians and long-distance cyclists as well as in the context of other outdoor activities.3-5 In all cases, patients developed perniosis at sites of exposure to cold or damp conditions.

Perniosis arising in patients using ice pack therapy is a rare and recent phenomenon, with only 3 other known reported cases.6,7 In all cases, including ours, patients reported treating chronic low back pain with ice packs for more than 2 hours per day. Clinical presentations included erythematous to purpuric plaques with ulceration on the lower back or buttocks that reoccurred with subsequent use of ice packs. No concomitant CTD was reported.6

Much controversy exists as to whether idiopathic perniosis (IP) increases susceptibility to acquiring an autoimmune disease or if IP is a form of CTD that follows a more indolent course.8 In a prospective study of 33 patients with underlying IP, no patients developed lupus erythematosus (LE), with a median follow-up of 38 months.9 A study by Crowson and Magro8 revealed that 18 of 39 patients with perniotic lesions had an associated systemic disease including LE, human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, cryofibrinogenemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, iritis, or Crohn disease. Of the 21 other patients who had no underlying CTD or systemic disease, 10 had a positive ANA test but no systemic symptoms; therefore, all 21 of these patients were classified as cases of IP.8

Cutaneous biopsy to distinguish between IP and autoimmune perniosis remains controversial; perniotic lesions and discoid LE share histopathologic features,9 as was evident with our case, which demonstrated overlapping findings of vacuolar change with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphoid infiltrates. Typical features of IP include thrombosed capillaries in the papillary dermis and lymphocytic exocytosis localized to the acrosyringia, whereas secondary perniosis has superficial and deep perivascular and perieccrine lymphocytic infiltrates with vascular thrombosis in the reticular dermis. Vascular ectasia, dermal mucinosis, basement membrane zone thickening, and erythrocyte extravasation are not reliable and may be seen in both cases.8 One study revealed the only significant difference between both entities was the perieccrine distribution of lymphocytic infiltrate in cases of IP (P=.007), whereas an absence of perieccrine involvement was noted in autoimmune cases.9

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may help differentiate IP from autoimmune perniosis. In a prospective study by Viguier et al,9 6 of 9 patients with IP had negative DIF and 3 had slight nonspecific C3 immunoreactivity of dermal vessels. Conversely, in patients with autoimmune perniosis, positive DIF with the lupus band test was seen in 3 of 7 patients, all who had a positive ANA test9; however, positive ANA levels also were reported in patients with autoimmune perniosis but negative DIF, suggesting that DIF lacks specificity in diagnosing autoimmune perniosis.

Although histopathologic findings bear similarities to LE, there are no guidelines to suggest for or against laboratory testing for CTD in patients presenting with perniosis. Some investigators have suggested that any patient with clinical features suggestive of perniosis should undergo laboratory evaluation including a complete blood cell count and assessment for antibodies to Ro, ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryofibrinogens, and antiphospholipid antibodies.9 Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation electrophoresis may be done to exclude monoclonal gammopathy.

For idiopathic cases, treatment is aimed at limiting or removing cold exposure. Patients should be advised regarding the use of long-term ice pack use and the potential development of perniosis. For chronic perniosis lasting beyond several weeks, a combination of a slow taper of oral prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine has been successful in patients with persistent lesions despite making environmental modifications.3 Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and nifedipine also have been effective in perniotic hand lesions.10

Conclusion

We report a rare case of perniosis on the buttocks that arose in a patient who utilized ice packs for treatment of chronic low back pain. Ice pack–induced perniosis may be an underreported entity. Histopathologic examination is nondescript, as overlapping features of perniosis and LE have been observed with no underlying CTD present. Correlation with patient history and clinical examination is paramount in diagnosis and management.

- Praminik T, Jha AK, Ghimire A. A retrospective study of cases with chilblains (perniosis) in Out Patient Department of Dermatology, Nepal Medical College and Teaching Hospital (NMCTH). Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13:190-192.

- Hochsinger C. Acute perniosis in submental region of child [in German]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1902;1:323-327.

- Stewart CL, Adler DJ, Jacobson A, et al. Equestrian perniosis: a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:237-240.

- Neal AJ, Jarman AM, Bennett TG. Perniosis in a long-distance cyclist crossing Mongolia. J Travel Med. 2012;19:66-68.

- Price RD, Murdoch DR. Perniosis (chilblains) of the thigh: report of five cases including four following river crossings. High Alt Met Biol. 2001;2:535-538.

- West SA, McCalmont TH, North JP. Ice-pack dermatosis: a cold-induced dermatitis with similarities to cold panniculitis and perniosis that histopathologically resembles lupus. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1314-1318.

- Haber JS, Ker KJ, Werth VP, et al. Ice‐pack dermatosis: a diagnositic pitfall for dermatopathologists that mimics lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1-4.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM. Idiopathic perniosis and its mimics: a clinical and histological study of 38 cases. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:478-484.

- Viguier M, Pinguier L, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features and immunologic variables in patients with severe chilblains. a study of the relationship to lupus erythematosus. Medicine. 2001;80:180-188.

- Patra AK, Das AL, Ramadasan P. Diltiazem vs. nifedipine in chilblains: a clinical trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:209-211.

Perniosis, or chilblain, is characterized by localized, tender, erythematous skin lesions that occur as an abnormal reaction to exposure to cold and damp conditions. Although the lesions favor the distal extremities, perniosis may present anywhere on the body. Lesions can develop within hours to days following exposure to temperature less than 10°C or damp environments with greater than 60% humidity.1 Acute cases may lead to pruritus and tenderness, whereas chronic cases may involve lesions that blister or ulcerate and can take weeks to heal. We report an unusual case of erythematous plaques arising on the buttocks of a 73-year-old woman using ice pack treatments for chronic low back pain.

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman presented with recurrent tender lesions on the buttocks of 5 years’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, and lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous plaques with areas of erosions on the left buttock with some involvement of the right buttock (Figure 1).

After a trial of oral valacyclovir for presumed herpes simplex infection provided no relief, a punch biopsy of the left buttock was performed, which revealed a cell-poor interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 2). Perieccrine lymphocytes were present in a small portion of the reticular dermis (Figure 3). The patient revealed she had been sitting on ice packs for several hours daily since the lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior to alleviate chronic low back pain.

Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, a diagnosis of perniosis secondary to ice pack therapy was made. An evaluation for concomitant or underlying connective tissue disease (CTD) including a complete blood cell count with sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), serum protein electrophoresis, and serum levels of cryoglobulins and complement components was unremarkable. Our patient was treated with simple analgesia and was encouraged to avoid direct contact with ice packs for extended periods of time. Because of her low back pain, she continued to use ice packs but readjusted them sporadically and decreased frequency of use. She had complete resolution of the lesions at 6-month follow-up.

Comment

Perniosis is a self-limited condition, manifesting as erythematous plaques or nodules following exposure to cold and damp conditions. It was first reported in 1902 by Hochsinger2 as tender submental plaques occurring in children after exposure to cold weather. Since then, reports of perniosis have been described in equestrians and long-distance cyclists as well as in the context of other outdoor activities.3-5 In all cases, patients developed perniosis at sites of exposure to cold or damp conditions.

Perniosis arising in patients using ice pack therapy is a rare and recent phenomenon, with only 3 other known reported cases.6,7 In all cases, including ours, patients reported treating chronic low back pain with ice packs for more than 2 hours per day. Clinical presentations included erythematous to purpuric plaques with ulceration on the lower back or buttocks that reoccurred with subsequent use of ice packs. No concomitant CTD was reported.6

Much controversy exists as to whether idiopathic perniosis (IP) increases susceptibility to acquiring an autoimmune disease or if IP is a form of CTD that follows a more indolent course.8 In a prospective study of 33 patients with underlying IP, no patients developed lupus erythematosus (LE), with a median follow-up of 38 months.9 A study by Crowson and Magro8 revealed that 18 of 39 patients with perniotic lesions had an associated systemic disease including LE, human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, cryofibrinogenemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, iritis, or Crohn disease. Of the 21 other patients who had no underlying CTD or systemic disease, 10 had a positive ANA test but no systemic symptoms; therefore, all 21 of these patients were classified as cases of IP.8

Cutaneous biopsy to distinguish between IP and autoimmune perniosis remains controversial; perniotic lesions and discoid LE share histopathologic features,9 as was evident with our case, which demonstrated overlapping findings of vacuolar change with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphoid infiltrates. Typical features of IP include thrombosed capillaries in the papillary dermis and lymphocytic exocytosis localized to the acrosyringia, whereas secondary perniosis has superficial and deep perivascular and perieccrine lymphocytic infiltrates with vascular thrombosis in the reticular dermis. Vascular ectasia, dermal mucinosis, basement membrane zone thickening, and erythrocyte extravasation are not reliable and may be seen in both cases.8 One study revealed the only significant difference between both entities was the perieccrine distribution of lymphocytic infiltrate in cases of IP (P=.007), whereas an absence of perieccrine involvement was noted in autoimmune cases.9

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may help differentiate IP from autoimmune perniosis. In a prospective study by Viguier et al,9 6 of 9 patients with IP had negative DIF and 3 had slight nonspecific C3 immunoreactivity of dermal vessels. Conversely, in patients with autoimmune perniosis, positive DIF with the lupus band test was seen in 3 of 7 patients, all who had a positive ANA test9; however, positive ANA levels also were reported in patients with autoimmune perniosis but negative DIF, suggesting that DIF lacks specificity in diagnosing autoimmune perniosis.

Although histopathologic findings bear similarities to LE, there are no guidelines to suggest for or against laboratory testing for CTD in patients presenting with perniosis. Some investigators have suggested that any patient with clinical features suggestive of perniosis should undergo laboratory evaluation including a complete blood cell count and assessment for antibodies to Ro, ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryofibrinogens, and antiphospholipid antibodies.9 Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation electrophoresis may be done to exclude monoclonal gammopathy.

For idiopathic cases, treatment is aimed at limiting or removing cold exposure. Patients should be advised regarding the use of long-term ice pack use and the potential development of perniosis. For chronic perniosis lasting beyond several weeks, a combination of a slow taper of oral prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine has been successful in patients with persistent lesions despite making environmental modifications.3 Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and nifedipine also have been effective in perniotic hand lesions.10

Conclusion

We report a rare case of perniosis on the buttocks that arose in a patient who utilized ice packs for treatment of chronic low back pain. Ice pack–induced perniosis may be an underreported entity. Histopathologic examination is nondescript, as overlapping features of perniosis and LE have been observed with no underlying CTD present. Correlation with patient history and clinical examination is paramount in diagnosis and management.

Perniosis, or chilblain, is characterized by localized, tender, erythematous skin lesions that occur as an abnormal reaction to exposure to cold and damp conditions. Although the lesions favor the distal extremities, perniosis may present anywhere on the body. Lesions can develop within hours to days following exposure to temperature less than 10°C or damp environments with greater than 60% humidity.1 Acute cases may lead to pruritus and tenderness, whereas chronic cases may involve lesions that blister or ulcerate and can take weeks to heal. We report an unusual case of erythematous plaques arising on the buttocks of a 73-year-old woman using ice pack treatments for chronic low back pain.

Case Report

A 73-year-old woman presented with recurrent tender lesions on the buttocks of 5 years’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, and lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous plaques with areas of erosions on the left buttock with some involvement of the right buttock (Figure 1).

After a trial of oral valacyclovir for presumed herpes simplex infection provided no relief, a punch biopsy of the left buttock was performed, which revealed a cell-poor interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 2). Perieccrine lymphocytes were present in a small portion of the reticular dermis (Figure 3). The patient revealed she had been sitting on ice packs for several hours daily since the lumbar spinal fusion surgery 5 years prior to alleviate chronic low back pain.

Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, a diagnosis of perniosis secondary to ice pack therapy was made. An evaluation for concomitant or underlying connective tissue disease (CTD) including a complete blood cell count with sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), serum protein electrophoresis, and serum levels of cryoglobulins and complement components was unremarkable. Our patient was treated with simple analgesia and was encouraged to avoid direct contact with ice packs for extended periods of time. Because of her low back pain, she continued to use ice packs but readjusted them sporadically and decreased frequency of use. She had complete resolution of the lesions at 6-month follow-up.

Comment

Perniosis is a self-limited condition, manifesting as erythematous plaques or nodules following exposure to cold and damp conditions. It was first reported in 1902 by Hochsinger2 as tender submental plaques occurring in children after exposure to cold weather. Since then, reports of perniosis have been described in equestrians and long-distance cyclists as well as in the context of other outdoor activities.3-5 In all cases, patients developed perniosis at sites of exposure to cold or damp conditions.

Perniosis arising in patients using ice pack therapy is a rare and recent phenomenon, with only 3 other known reported cases.6,7 In all cases, including ours, patients reported treating chronic low back pain with ice packs for more than 2 hours per day. Clinical presentations included erythematous to purpuric plaques with ulceration on the lower back or buttocks that reoccurred with subsequent use of ice packs. No concomitant CTD was reported.6

Much controversy exists as to whether idiopathic perniosis (IP) increases susceptibility to acquiring an autoimmune disease or if IP is a form of CTD that follows a more indolent course.8 In a prospective study of 33 patients with underlying IP, no patients developed lupus erythematosus (LE), with a median follow-up of 38 months.9 A study by Crowson and Magro8 revealed that 18 of 39 patients with perniotic lesions had an associated systemic disease including LE, human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, cryofibrinogenemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, iritis, or Crohn disease. Of the 21 other patients who had no underlying CTD or systemic disease, 10 had a positive ANA test but no systemic symptoms; therefore, all 21 of these patients were classified as cases of IP.8

Cutaneous biopsy to distinguish between IP and autoimmune perniosis remains controversial; perniotic lesions and discoid LE share histopathologic features,9 as was evident with our case, which demonstrated overlapping findings of vacuolar change with superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphoid infiltrates. Typical features of IP include thrombosed capillaries in the papillary dermis and lymphocytic exocytosis localized to the acrosyringia, whereas secondary perniosis has superficial and deep perivascular and perieccrine lymphocytic infiltrates with vascular thrombosis in the reticular dermis. Vascular ectasia, dermal mucinosis, basement membrane zone thickening, and erythrocyte extravasation are not reliable and may be seen in both cases.8 One study revealed the only significant difference between both entities was the perieccrine distribution of lymphocytic infiltrate in cases of IP (P=.007), whereas an absence of perieccrine involvement was noted in autoimmune cases.9

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may help differentiate IP from autoimmune perniosis. In a prospective study by Viguier et al,9 6 of 9 patients with IP had negative DIF and 3 had slight nonspecific C3 immunoreactivity of dermal vessels. Conversely, in patients with autoimmune perniosis, positive DIF with the lupus band test was seen in 3 of 7 patients, all who had a positive ANA test9; however, positive ANA levels also were reported in patients with autoimmune perniosis but negative DIF, suggesting that DIF lacks specificity in diagnosing autoimmune perniosis.

Although histopathologic findings bear similarities to LE, there are no guidelines to suggest for or against laboratory testing for CTD in patients presenting with perniosis. Some investigators have suggested that any patient with clinical features suggestive of perniosis should undergo laboratory evaluation including a complete blood cell count and assessment for antibodies to Ro, ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryofibrinogens, and antiphospholipid antibodies.9 Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation electrophoresis may be done to exclude monoclonal gammopathy.

For idiopathic cases, treatment is aimed at limiting or removing cold exposure. Patients should be advised regarding the use of long-term ice pack use and the potential development of perniosis. For chronic perniosis lasting beyond several weeks, a combination of a slow taper of oral prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and quinacrine has been successful in patients with persistent lesions despite making environmental modifications.3 Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and nifedipine also have been effective in perniotic hand lesions.10

Conclusion

We report a rare case of perniosis on the buttocks that arose in a patient who utilized ice packs for treatment of chronic low back pain. Ice pack–induced perniosis may be an underreported entity. Histopathologic examination is nondescript, as overlapping features of perniosis and LE have been observed with no underlying CTD present. Correlation with patient history and clinical examination is paramount in diagnosis and management.

- Praminik T, Jha AK, Ghimire A. A retrospective study of cases with chilblains (perniosis) in Out Patient Department of Dermatology, Nepal Medical College and Teaching Hospital (NMCTH). Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13:190-192.

- Hochsinger C. Acute perniosis in submental region of child [in German]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1902;1:323-327.

- Stewart CL, Adler DJ, Jacobson A, et al. Equestrian perniosis: a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:237-240.

- Neal AJ, Jarman AM, Bennett TG. Perniosis in a long-distance cyclist crossing Mongolia. J Travel Med. 2012;19:66-68.

- Price RD, Murdoch DR. Perniosis (chilblains) of the thigh: report of five cases including four following river crossings. High Alt Met Biol. 2001;2:535-538.

- West SA, McCalmont TH, North JP. Ice-pack dermatosis: a cold-induced dermatitis with similarities to cold panniculitis and perniosis that histopathologically resembles lupus. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1314-1318.

- Haber JS, Ker KJ, Werth VP, et al. Ice‐pack dermatosis: a diagnositic pitfall for dermatopathologists that mimics lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1-4.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM. Idiopathic perniosis and its mimics: a clinical and histological study of 38 cases. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:478-484.

- Viguier M, Pinguier L, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features and immunologic variables in patients with severe chilblains. a study of the relationship to lupus erythematosus. Medicine. 2001;80:180-188.

- Patra AK, Das AL, Ramadasan P. Diltiazem vs. nifedipine in chilblains: a clinical trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:209-211.

- Praminik T, Jha AK, Ghimire A. A retrospective study of cases with chilblains (perniosis) in Out Patient Department of Dermatology, Nepal Medical College and Teaching Hospital (NMCTH). Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13:190-192.

- Hochsinger C. Acute perniosis in submental region of child [in German]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1902;1:323-327.

- Stewart CL, Adler DJ, Jacobson A, et al. Equestrian perniosis: a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:237-240.

- Neal AJ, Jarman AM, Bennett TG. Perniosis in a long-distance cyclist crossing Mongolia. J Travel Med. 2012;19:66-68.

- Price RD, Murdoch DR. Perniosis (chilblains) of the thigh: report of five cases including four following river crossings. High Alt Met Biol. 2001;2:535-538.

- West SA, McCalmont TH, North JP. Ice-pack dermatosis: a cold-induced dermatitis with similarities to cold panniculitis and perniosis that histopathologically resembles lupus. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1314-1318.

- Haber JS, Ker KJ, Werth VP, et al. Ice‐pack dermatosis: a diagnositic pitfall for dermatopathologists that mimics lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1-4.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM. Idiopathic perniosis and its mimics: a clinical and histological study of 38 cases. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:478-484.

- Viguier M, Pinguier L, Cavelier-Balloy B, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features and immunologic variables in patients with severe chilblains. a study of the relationship to lupus erythematosus. Medicine. 2001;80:180-188.

- Patra AK, Das AL, Ramadasan P. Diltiazem vs. nifedipine in chilblains: a clinical trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:209-211.

Practice Points

- Ice pack-induced perniosis is a rare condition that can occur in patients using long-term ice pack therapy.

- This entity histopathologically mimics cutaneous lupus erythematosus and can present a diagnostic challenge.

- A thorough clinical history and awareness of this diagnosis is essential for diagnostic accuracy.