User login

Hospital medicine groups are getting larger

What are the implications for your workplace?

Although readers will be forgiven for missing the subtle change, the tables in the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report underwent a landmark structural change that echoes the growth of our field. In the latest SoHM Report, the hospital medicine group (HMG) size categories all increased significantly to reflect the fact that hospitalist groups have grown from a median of 9 physician full time equivalents (FTE) in 2016 to a median of 15.2 employed/contracted FTE (excluding FTE provided by locum tenens providers) in 2020.

For many years, the Report considered “large” adult HMGs to be those with 30 or more FTE of physicians, and smaller groups were organized by FTE categories of <5, 5-9, 10-19, and 20-29. Now the SoHM Report describes a large HMG as 50 employed/contracted FTE or greater, a category that represents 12.7% of HMGs serving adults. The other categories expanded to <5, 5-14, 15-29, and 30-49, respectively. Overall, HMGs are growing in size, and the SoHM displays new data slices that help leaders to compare their group to modern peers.

There are some caveats to consider. First, these figures only represent physician FTE, and essentially all these large groups employ NP/PA hospitalists as well. Second, these HMGs typically employ some part-time and contracted PRN physicians in this FTE count. In combination, these two factors mean that large HMGs often employ many more than 50 individual clinicians. In fact, the average number of physicians in this cohort was 72.3 before counting NP/PAs and locums. Third, do not interpret the portion of large groups in the survey (12.7%) as insignificant. Because each one employs so many total hospitalists, large HMGs collectively represent a common work environment for many hospitalists in the US. Lastly, although pediatric HMGs have grown, far fewer (3.1%) have over 50 FTE, so this column focuses on HMGs serving adults.

Why does it matter that groups are growing in size? The SoHM Report offers extensive data to answer this question. Here are a couple of highlights but consider buying the report to dig deeper. First, large groups are far more likely to offer variable scheduling. Although the 7-on, 7-off scheduling pattern is still the norm in all group sizes, large HMGs are most likely to offer something flexible that might enhance career sustainability for hospitalists. Second, large groups are the most likely to employ a few hospitalists with extra training, whether that be geriatrics, palliative care, pediatrics, or a medicine subspecialty. Working in a large group means you can ask for curbside consults from a diverse and well-trained bunch of colleagues. Third, large groups were most likely to employ nocturnists, meaning fewer night shifts are allocated to the hospitalists who want to focus on daytime work. From an individual perspective, there is a lot to like about working in a large HMG.

There are some drawbacks to larger groups, of course. Large groups can be less socially cohesive and the costs of managing 70-100 hospitalists typically grow well past the capacity of a single group leader. My personal belief is that these downsides can be solved through economies of scale and skilled management teams. In addition, a large group can afford to dedicate leadership FTE to niche hospitalist needs, such as career development and coaching, which are difficult to fund in small practices. This also provides more opportunities for staff hospitalists to begin taking on some leadership or administrative duties or branch out into related areas such as quality improvement, case management physician advisor roles, or IT expertise.

Ultimately, large groups typically represent the maturation of an HMG within a large hospital – it signifies that the hospital relies on that group to deliver great patient outcomes in every corner of the hospital. Where you practice remains a personal choice, but the emergence of large groups hints at the clout and sophistication hospitalists can build by banding together. Learn more about the full 2020 SoHM Report at hospitalmedicine.org/sohm.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

What are the implications for your workplace?

What are the implications for your workplace?

Although readers will be forgiven for missing the subtle change, the tables in the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report underwent a landmark structural change that echoes the growth of our field. In the latest SoHM Report, the hospital medicine group (HMG) size categories all increased significantly to reflect the fact that hospitalist groups have grown from a median of 9 physician full time equivalents (FTE) in 2016 to a median of 15.2 employed/contracted FTE (excluding FTE provided by locum tenens providers) in 2020.

For many years, the Report considered “large” adult HMGs to be those with 30 or more FTE of physicians, and smaller groups were organized by FTE categories of <5, 5-9, 10-19, and 20-29. Now the SoHM Report describes a large HMG as 50 employed/contracted FTE or greater, a category that represents 12.7% of HMGs serving adults. The other categories expanded to <5, 5-14, 15-29, and 30-49, respectively. Overall, HMGs are growing in size, and the SoHM displays new data slices that help leaders to compare their group to modern peers.

There are some caveats to consider. First, these figures only represent physician FTE, and essentially all these large groups employ NP/PA hospitalists as well. Second, these HMGs typically employ some part-time and contracted PRN physicians in this FTE count. In combination, these two factors mean that large HMGs often employ many more than 50 individual clinicians. In fact, the average number of physicians in this cohort was 72.3 before counting NP/PAs and locums. Third, do not interpret the portion of large groups in the survey (12.7%) as insignificant. Because each one employs so many total hospitalists, large HMGs collectively represent a common work environment for many hospitalists in the US. Lastly, although pediatric HMGs have grown, far fewer (3.1%) have over 50 FTE, so this column focuses on HMGs serving adults.

Why does it matter that groups are growing in size? The SoHM Report offers extensive data to answer this question. Here are a couple of highlights but consider buying the report to dig deeper. First, large groups are far more likely to offer variable scheduling. Although the 7-on, 7-off scheduling pattern is still the norm in all group sizes, large HMGs are most likely to offer something flexible that might enhance career sustainability for hospitalists. Second, large groups are the most likely to employ a few hospitalists with extra training, whether that be geriatrics, palliative care, pediatrics, or a medicine subspecialty. Working in a large group means you can ask for curbside consults from a diverse and well-trained bunch of colleagues. Third, large groups were most likely to employ nocturnists, meaning fewer night shifts are allocated to the hospitalists who want to focus on daytime work. From an individual perspective, there is a lot to like about working in a large HMG.

There are some drawbacks to larger groups, of course. Large groups can be less socially cohesive and the costs of managing 70-100 hospitalists typically grow well past the capacity of a single group leader. My personal belief is that these downsides can be solved through economies of scale and skilled management teams. In addition, a large group can afford to dedicate leadership FTE to niche hospitalist needs, such as career development and coaching, which are difficult to fund in small practices. This also provides more opportunities for staff hospitalists to begin taking on some leadership or administrative duties or branch out into related areas such as quality improvement, case management physician advisor roles, or IT expertise.

Ultimately, large groups typically represent the maturation of an HMG within a large hospital – it signifies that the hospital relies on that group to deliver great patient outcomes in every corner of the hospital. Where you practice remains a personal choice, but the emergence of large groups hints at the clout and sophistication hospitalists can build by banding together. Learn more about the full 2020 SoHM Report at hospitalmedicine.org/sohm.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Although readers will be forgiven for missing the subtle change, the tables in the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report underwent a landmark structural change that echoes the growth of our field. In the latest SoHM Report, the hospital medicine group (HMG) size categories all increased significantly to reflect the fact that hospitalist groups have grown from a median of 9 physician full time equivalents (FTE) in 2016 to a median of 15.2 employed/contracted FTE (excluding FTE provided by locum tenens providers) in 2020.

For many years, the Report considered “large” adult HMGs to be those with 30 or more FTE of physicians, and smaller groups were organized by FTE categories of <5, 5-9, 10-19, and 20-29. Now the SoHM Report describes a large HMG as 50 employed/contracted FTE or greater, a category that represents 12.7% of HMGs serving adults. The other categories expanded to <5, 5-14, 15-29, and 30-49, respectively. Overall, HMGs are growing in size, and the SoHM displays new data slices that help leaders to compare their group to modern peers.

There are some caveats to consider. First, these figures only represent physician FTE, and essentially all these large groups employ NP/PA hospitalists as well. Second, these HMGs typically employ some part-time and contracted PRN physicians in this FTE count. In combination, these two factors mean that large HMGs often employ many more than 50 individual clinicians. In fact, the average number of physicians in this cohort was 72.3 before counting NP/PAs and locums. Third, do not interpret the portion of large groups in the survey (12.7%) as insignificant. Because each one employs so many total hospitalists, large HMGs collectively represent a common work environment for many hospitalists in the US. Lastly, although pediatric HMGs have grown, far fewer (3.1%) have over 50 FTE, so this column focuses on HMGs serving adults.

Why does it matter that groups are growing in size? The SoHM Report offers extensive data to answer this question. Here are a couple of highlights but consider buying the report to dig deeper. First, large groups are far more likely to offer variable scheduling. Although the 7-on, 7-off scheduling pattern is still the norm in all group sizes, large HMGs are most likely to offer something flexible that might enhance career sustainability for hospitalists. Second, large groups are the most likely to employ a few hospitalists with extra training, whether that be geriatrics, palliative care, pediatrics, or a medicine subspecialty. Working in a large group means you can ask for curbside consults from a diverse and well-trained bunch of colleagues. Third, large groups were most likely to employ nocturnists, meaning fewer night shifts are allocated to the hospitalists who want to focus on daytime work. From an individual perspective, there is a lot to like about working in a large HMG.

There are some drawbacks to larger groups, of course. Large groups can be less socially cohesive and the costs of managing 70-100 hospitalists typically grow well past the capacity of a single group leader. My personal belief is that these downsides can be solved through economies of scale and skilled management teams. In addition, a large group can afford to dedicate leadership FTE to niche hospitalist needs, such as career development and coaching, which are difficult to fund in small practices. This also provides more opportunities for staff hospitalists to begin taking on some leadership or administrative duties or branch out into related areas such as quality improvement, case management physician advisor roles, or IT expertise.

Ultimately, large groups typically represent the maturation of an HMG within a large hospital – it signifies that the hospital relies on that group to deliver great patient outcomes in every corner of the hospital. Where you practice remains a personal choice, but the emergence of large groups hints at the clout and sophistication hospitalists can build by banding together. Learn more about the full 2020 SoHM Report at hospitalmedicine.org/sohm.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

How do hospital medicine groups deal with staffing shortages?

Persistent demand for hospitalists nationally

During the last two decades, the United States health care labor market had an almost insatiable appetite for hospitalists, driving the specialty from nothing to over 50,000 members. Evidence of persistent demand for hospitalists abounds in the freshly released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report: rising salaries, growing responsibility for the overall hospital census, and a diversifying scope of services.

The SoHM offers fascinating and detailed insights into these trends, as well as hundreds of other aspects of the field’s growth. Unfortunately, this expanding and dynamic labor market has a challenging side for hospitals, management companies, and hospitalist group leaders – we are constantly recruiting and dealing with open positions!

As a multisite leader at an academic health system, I’m looking toward the next season of recruitment with excitement. In the fall and winter we’re fortunate to receive applications from the best and brightest graduating residents and hospitalists. I realize this is a blessing, particularly compared with programs in rural areas that may not hear from many applicants. However, even when we succeed at filling the openings, there is an inevitable trickle of talent out of our clinical labor pool during the spring and summer. One person is invited to spend 20% of their time leading a teaching program, another secures a highly coveted grant, and yet another has to move because their spouse is relocated. By then, we don’t have a packed roster of applicants and have to solve the challenge in other ways. What does the typical hospital medicine program do when faced with this circumstance?

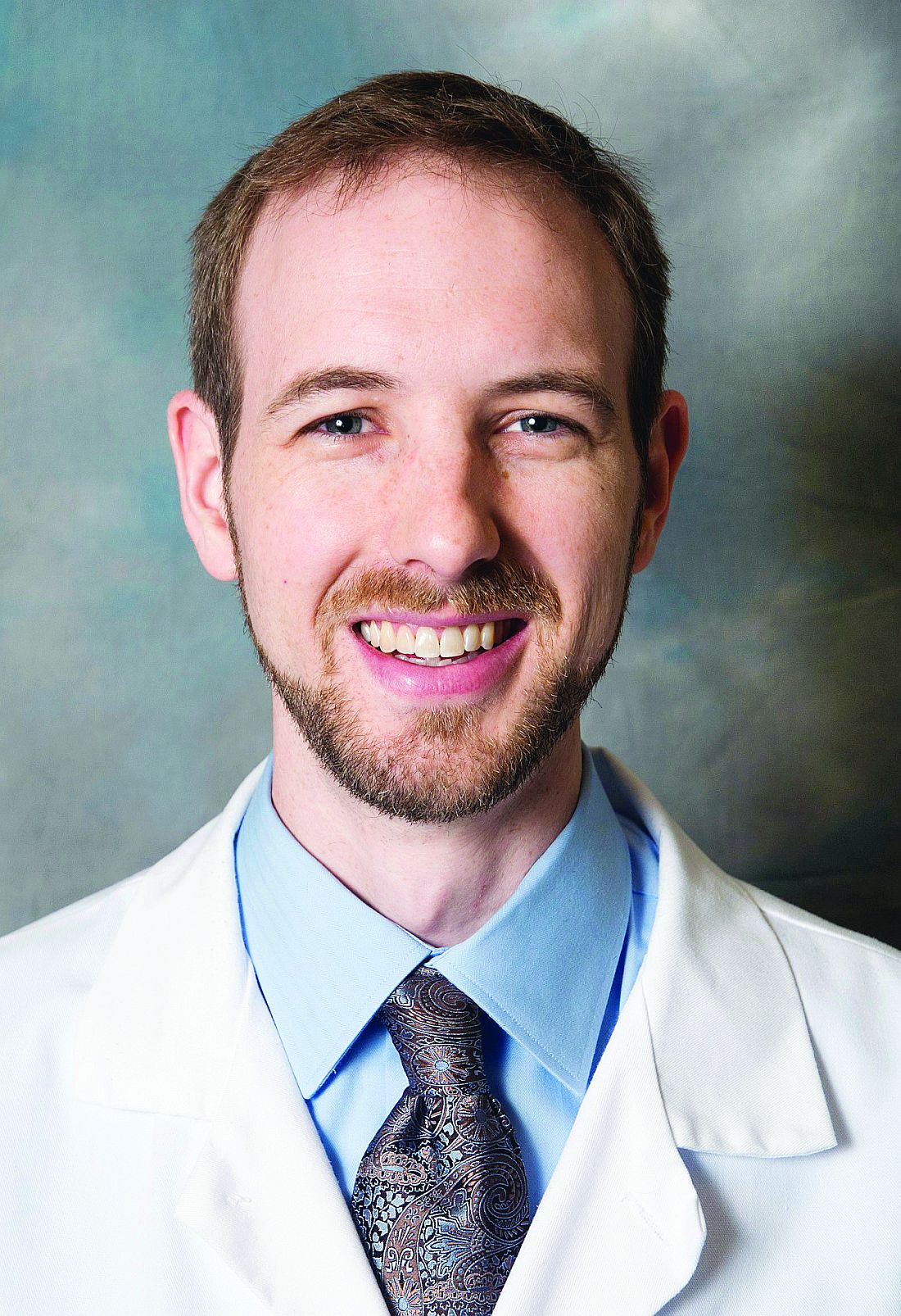

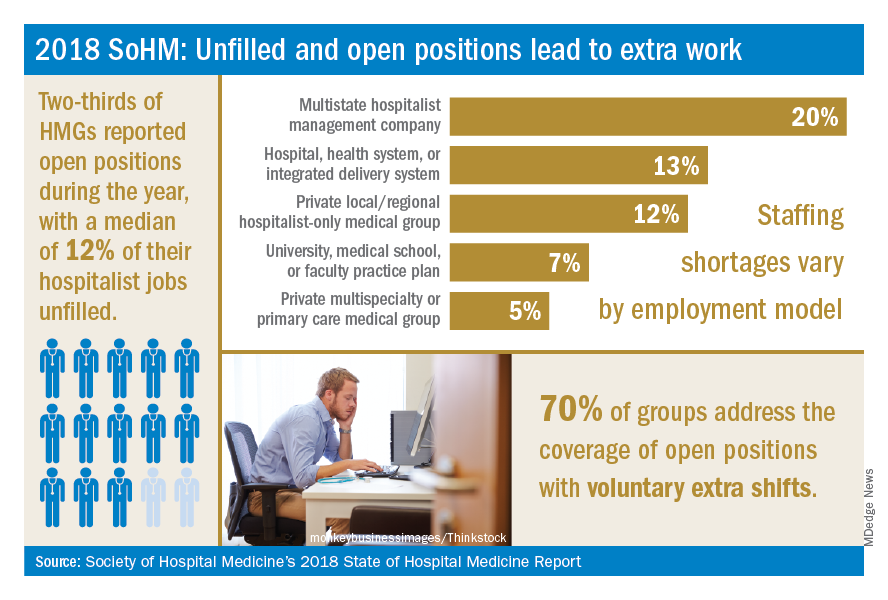

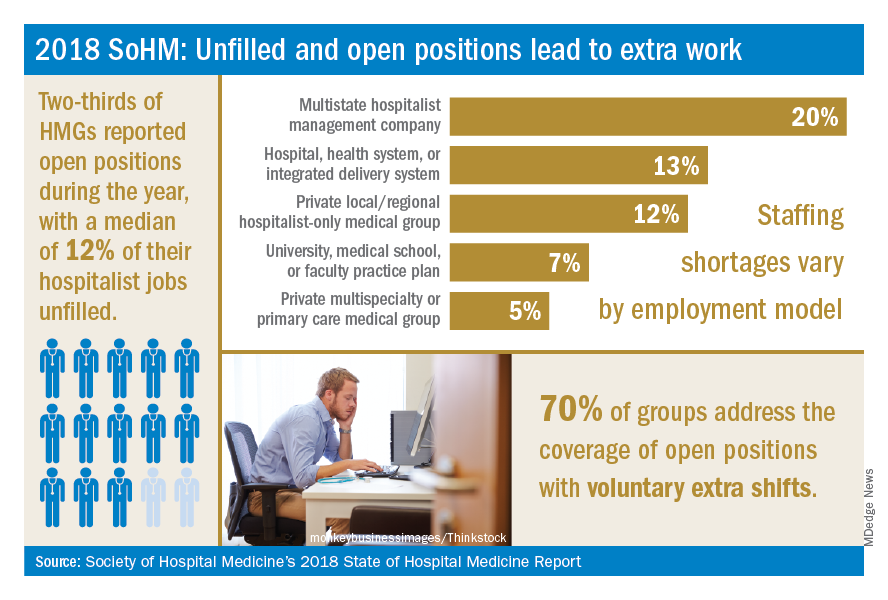

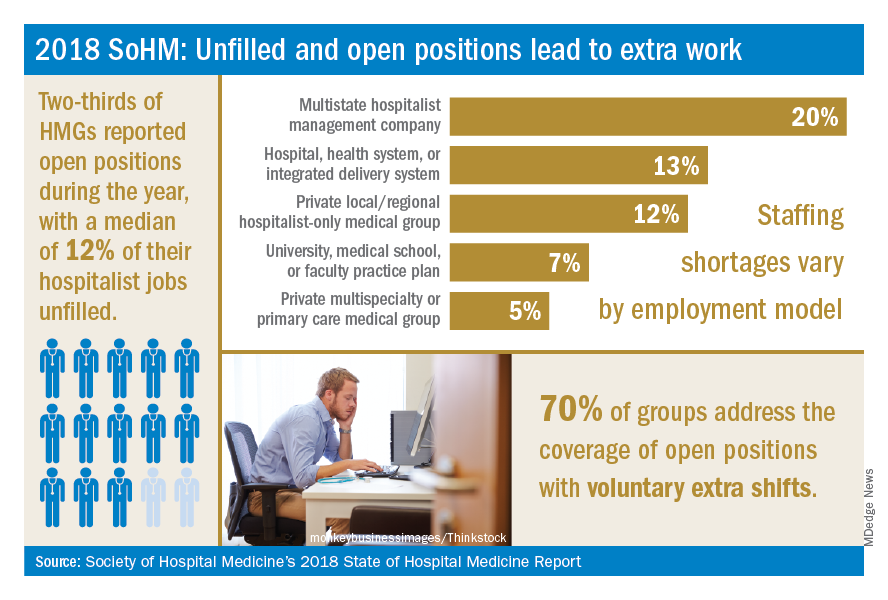

The 2018 SoHM survey first asked program leaders whether they had open and unfilled physician positions during the last year because of turnover, growth, or other factors. On average, 66% of groups serving adults and 48% of groups serving children said “yes.” For the job seekers out there, take note of some important regional differences: The regions with the highest percentage of programs dealing with unfilled positions were the East and West Coasts at 79% and 73%, respectively.

Next, the survey asked respondents to describe the percentage of total approved physician staffing that was open or unfilled during the year. On average, 12% of positions went unfilled, with important variation between different types of employers. For a typical HM group with 15 full-time equivalents, that means constantly working short two physicians!

Not only is it hard for group leaders to manage chronic understaffing, it definitely takes a toll on the group. We asked leaders to describe all of the ways their groups address coverage of the open positions. The most common tactics were for existing hospitalists to perform voluntary extra shifts (70%) and the use of moonlighters (57%). Also important were the use of locum tenens physicians (44%) and just leaving some shifts uncovered (31%).

The last option might work in a large group, where everyone can pick up an extra couple of patients, but it nonetheless degrades continuity and care progression. In a small group, leaving shifts uncovered sounds like a recipe for burnout and unsafe care – hopefully subsequent surveys will find that we can avoid that approach! Obviously, the solutions must be tailored to the group, their resources, and the alternative sources of labor available in that locality.

The SoHM report provides insight into how this is commonly handled by different employers and in different regions – we encourage anyone who is interested to purchase the report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm) to dig deeper. For better or worse, the issue of unfilled positions looks likely to persist for the intermediate future. The exciting rise of hospital medicine against the backdrop of an aging population means job security, rising income, and opportunities for many to live where they choose. Until the job market saturates, though, we’ll all find ourselves looking at email inboxes with a request or two to pick up an extra shift!

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

Society of Hospital Medicine. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. pp. 89, 90, 181, 152.

Persistent demand for hospitalists nationally

Persistent demand for hospitalists nationally

During the last two decades, the United States health care labor market had an almost insatiable appetite for hospitalists, driving the specialty from nothing to over 50,000 members. Evidence of persistent demand for hospitalists abounds in the freshly released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report: rising salaries, growing responsibility for the overall hospital census, and a diversifying scope of services.

The SoHM offers fascinating and detailed insights into these trends, as well as hundreds of other aspects of the field’s growth. Unfortunately, this expanding and dynamic labor market has a challenging side for hospitals, management companies, and hospitalist group leaders – we are constantly recruiting and dealing with open positions!

As a multisite leader at an academic health system, I’m looking toward the next season of recruitment with excitement. In the fall and winter we’re fortunate to receive applications from the best and brightest graduating residents and hospitalists. I realize this is a blessing, particularly compared with programs in rural areas that may not hear from many applicants. However, even when we succeed at filling the openings, there is an inevitable trickle of talent out of our clinical labor pool during the spring and summer. One person is invited to spend 20% of their time leading a teaching program, another secures a highly coveted grant, and yet another has to move because their spouse is relocated. By then, we don’t have a packed roster of applicants and have to solve the challenge in other ways. What does the typical hospital medicine program do when faced with this circumstance?

The 2018 SoHM survey first asked program leaders whether they had open and unfilled physician positions during the last year because of turnover, growth, or other factors. On average, 66% of groups serving adults and 48% of groups serving children said “yes.” For the job seekers out there, take note of some important regional differences: The regions with the highest percentage of programs dealing with unfilled positions were the East and West Coasts at 79% and 73%, respectively.

Next, the survey asked respondents to describe the percentage of total approved physician staffing that was open or unfilled during the year. On average, 12% of positions went unfilled, with important variation between different types of employers. For a typical HM group with 15 full-time equivalents, that means constantly working short two physicians!

Not only is it hard for group leaders to manage chronic understaffing, it definitely takes a toll on the group. We asked leaders to describe all of the ways their groups address coverage of the open positions. The most common tactics were for existing hospitalists to perform voluntary extra shifts (70%) and the use of moonlighters (57%). Also important were the use of locum tenens physicians (44%) and just leaving some shifts uncovered (31%).

The last option might work in a large group, where everyone can pick up an extra couple of patients, but it nonetheless degrades continuity and care progression. In a small group, leaving shifts uncovered sounds like a recipe for burnout and unsafe care – hopefully subsequent surveys will find that we can avoid that approach! Obviously, the solutions must be tailored to the group, their resources, and the alternative sources of labor available in that locality.

The SoHM report provides insight into how this is commonly handled by different employers and in different regions – we encourage anyone who is interested to purchase the report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm) to dig deeper. For better or worse, the issue of unfilled positions looks likely to persist for the intermediate future. The exciting rise of hospital medicine against the backdrop of an aging population means job security, rising income, and opportunities for many to live where they choose. Until the job market saturates, though, we’ll all find ourselves looking at email inboxes with a request or two to pick up an extra shift!

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

Society of Hospital Medicine. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. pp. 89, 90, 181, 152.

During the last two decades, the United States health care labor market had an almost insatiable appetite for hospitalists, driving the specialty from nothing to over 50,000 members. Evidence of persistent demand for hospitalists abounds in the freshly released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report: rising salaries, growing responsibility for the overall hospital census, and a diversifying scope of services.

The SoHM offers fascinating and detailed insights into these trends, as well as hundreds of other aspects of the field’s growth. Unfortunately, this expanding and dynamic labor market has a challenging side for hospitals, management companies, and hospitalist group leaders – we are constantly recruiting and dealing with open positions!

As a multisite leader at an academic health system, I’m looking toward the next season of recruitment with excitement. In the fall and winter we’re fortunate to receive applications from the best and brightest graduating residents and hospitalists. I realize this is a blessing, particularly compared with programs in rural areas that may not hear from many applicants. However, even when we succeed at filling the openings, there is an inevitable trickle of talent out of our clinical labor pool during the spring and summer. One person is invited to spend 20% of their time leading a teaching program, another secures a highly coveted grant, and yet another has to move because their spouse is relocated. By then, we don’t have a packed roster of applicants and have to solve the challenge in other ways. What does the typical hospital medicine program do when faced with this circumstance?

The 2018 SoHM survey first asked program leaders whether they had open and unfilled physician positions during the last year because of turnover, growth, or other factors. On average, 66% of groups serving adults and 48% of groups serving children said “yes.” For the job seekers out there, take note of some important regional differences: The regions with the highest percentage of programs dealing with unfilled positions were the East and West Coasts at 79% and 73%, respectively.

Next, the survey asked respondents to describe the percentage of total approved physician staffing that was open or unfilled during the year. On average, 12% of positions went unfilled, with important variation between different types of employers. For a typical HM group with 15 full-time equivalents, that means constantly working short two physicians!

Not only is it hard for group leaders to manage chronic understaffing, it definitely takes a toll on the group. We asked leaders to describe all of the ways their groups address coverage of the open positions. The most common tactics were for existing hospitalists to perform voluntary extra shifts (70%) and the use of moonlighters (57%). Also important were the use of locum tenens physicians (44%) and just leaving some shifts uncovered (31%).

The last option might work in a large group, where everyone can pick up an extra couple of patients, but it nonetheless degrades continuity and care progression. In a small group, leaving shifts uncovered sounds like a recipe for burnout and unsafe care – hopefully subsequent surveys will find that we can avoid that approach! Obviously, the solutions must be tailored to the group, their resources, and the alternative sources of labor available in that locality.

The SoHM report provides insight into how this is commonly handled by different employers and in different regions – we encourage anyone who is interested to purchase the report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm) to dig deeper. For better or worse, the issue of unfilled positions looks likely to persist for the intermediate future. The exciting rise of hospital medicine against the backdrop of an aging population means job security, rising income, and opportunities for many to live where they choose. Until the job market saturates, though, we’ll all find ourselves looking at email inboxes with a request or two to pick up an extra shift!

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

Society of Hospital Medicine. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. pp. 89, 90, 181, 152.

What do you call a general medicine hospitalist who focuses on comanaging with a single medical subspecialty?

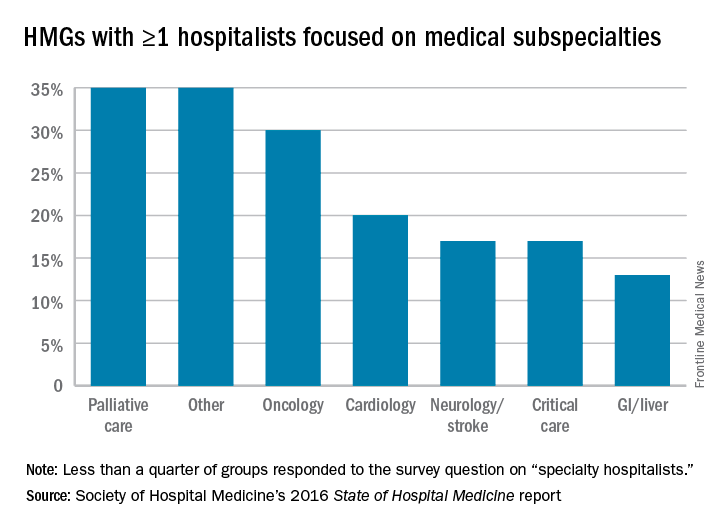

For more than 2 decades, U.S. health systems have drawn on hospitalists’ expertise to lower length of stay and enhance safety for general medical patients. Many hospital medicine groups have extended this successful practice model across a growing list of services, stretching the role of generalists as far as it can go. While a diverse scope of practice excites some hospitalists, others find career satisfaction with a specific patient population. Some even balk at rotating through all of the possible primary and comanagement services staffed by their group. A growing number of job opportunities have emerged for individuals who are drawn to a specialized patient population but either remain generalist at heart or don’t want to complete a fellowship.

The latest State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report provides new insight into this trend, which brings our unique talents to subspecialty populations.

To understand the prevalence of this practice style, the following topic was added to the 2016 SoHM survey: “Some hospital medicine groups include hospitalists who focus their practice exclusively or predominantly in a single medical subspecialty area (e.g., a general internist who exclusively cares for patients on an oncology service in collaboration with oncologists).” Groups were asked to report whether one or more members of their group practiced this way and with which specialty. Although less than a quarter of groups responded to this question, we learned that a substantial portion of respondent groups employ such individuals (see table below).

We look forward to tracking this area with subsequent surveys. Already, national meetings are developing for specialty hospitalists (for example, in oncology), and we see opportunities for specialty hospitalists to network through the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting and HMX online. My prediction is for growth in the number of groups reporting the employment of specialty hospitalists, but only time will tell. Hospital medicine group leaders should consider both participating in the next SOHM survey and digging into the details of the current report as ways to advance the best practices for developing specialty hospitalist positions.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

For more than 2 decades, U.S. health systems have drawn on hospitalists’ expertise to lower length of stay and enhance safety for general medical patients. Many hospital medicine groups have extended this successful practice model across a growing list of services, stretching the role of generalists as far as it can go. While a diverse scope of practice excites some hospitalists, others find career satisfaction with a specific patient population. Some even balk at rotating through all of the possible primary and comanagement services staffed by their group. A growing number of job opportunities have emerged for individuals who are drawn to a specialized patient population but either remain generalist at heart or don’t want to complete a fellowship.

The latest State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report provides new insight into this trend, which brings our unique talents to subspecialty populations.

To understand the prevalence of this practice style, the following topic was added to the 2016 SoHM survey: “Some hospital medicine groups include hospitalists who focus their practice exclusively or predominantly in a single medical subspecialty area (e.g., a general internist who exclusively cares for patients on an oncology service in collaboration with oncologists).” Groups were asked to report whether one or more members of their group practiced this way and with which specialty. Although less than a quarter of groups responded to this question, we learned that a substantial portion of respondent groups employ such individuals (see table below).

We look forward to tracking this area with subsequent surveys. Already, national meetings are developing for specialty hospitalists (for example, in oncology), and we see opportunities for specialty hospitalists to network through the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting and HMX online. My prediction is for growth in the number of groups reporting the employment of specialty hospitalists, but only time will tell. Hospital medicine group leaders should consider both participating in the next SOHM survey and digging into the details of the current report as ways to advance the best practices for developing specialty hospitalist positions.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

For more than 2 decades, U.S. health systems have drawn on hospitalists’ expertise to lower length of stay and enhance safety for general medical patients. Many hospital medicine groups have extended this successful practice model across a growing list of services, stretching the role of generalists as far as it can go. While a diverse scope of practice excites some hospitalists, others find career satisfaction with a specific patient population. Some even balk at rotating through all of the possible primary and comanagement services staffed by their group. A growing number of job opportunities have emerged for individuals who are drawn to a specialized patient population but either remain generalist at heart or don’t want to complete a fellowship.

The latest State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report provides new insight into this trend, which brings our unique talents to subspecialty populations.

To understand the prevalence of this practice style, the following topic was added to the 2016 SoHM survey: “Some hospital medicine groups include hospitalists who focus their practice exclusively or predominantly in a single medical subspecialty area (e.g., a general internist who exclusively cares for patients on an oncology service in collaboration with oncologists).” Groups were asked to report whether one or more members of their group practiced this way and with which specialty. Although less than a quarter of groups responded to this question, we learned that a substantial portion of respondent groups employ such individuals (see table below).

We look forward to tracking this area with subsequent surveys. Already, national meetings are developing for specialty hospitalists (for example, in oncology), and we see opportunities for specialty hospitalists to network through the Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting and HMX online. My prediction is for growth in the number of groups reporting the employment of specialty hospitalists, but only time will tell. Hospital medicine group leaders should consider both participating in the next SOHM survey and digging into the details of the current report as ways to advance the best practices for developing specialty hospitalist positions.

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.