User login

Should the adnexae be removed during hysterectomy for benign disease to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer?

The decision-making surrounding gynecologic surgery for benign disease is increasingly complex. Patients and their physicians must balance the potential benefits of salpingo-oophorectomy against possible adverse consequence as they consider various health goals, including longevity, cancer risk, and quality of life.

Chan and colleagues add important data to our understanding of this equation. Analyzing a large cohort of patients from Kaiser Permanente Northern California who underwent hysterectomy for benign disease, they found that removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries significantly reduced the risk of developing ovarian cancer. The incidence of ovarian cancer per 100,000 person-years was 26.2 for women undergoing hysterectomy alone (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–37.0), 17.5 for hysterectomy with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0–39.1), and 1.7 for hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.4–3.0).

The hazard ratio (HR) for ovarian cancer was 0.58 for women undergoing unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.18–1.90) and 0.12 for women undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.05–0.28), compared with women undergoing hysterectomy alone.

Notable strengths of the analysis include the large size of the study population and the duration of patient follow-up (18 years). The authors acknowledge several limitations of the study, including the lack of data on BRCA mutation status and family history of cancer, as well as several other demographic data points possibly relevant to a risk of developing adnexal or peritoneal malignancy.

Related article: What is the gynecologist’s role in the care of BRCA previvors? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2013)

Keep these findings in context

As the authors discuss, this report should be considered in the context of other work suggesting that the lower mortality rate associated with ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease arises mostly from a protective effect against cardiovascular disease (CVD)—perhaps from subclinical hormone production following menopause. Given that CVD remains the leading cause of death among American women, an individualized assessment of risk is necessary when planning the extent of surgery in this circumstance.

Related article: Oophorectomy or salpingectomy—which makes more sense? William H. Parker, MD (March 2014)

It also is interesting to consider the authors’ finding of a notable but statistically insignificant decrease in the risk of ovarian cancer associated with removal of only one tube and ovary. However, recognizing the possible limitations of their demographic information on this point, they suggest that this may be an area for further investigation, which would necessarily include characterization of the trends in the laterality of adnexal cancers. The preservation of hormonal function makes this an interesting option to consider.

We also need to further investigate the role of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, with ovarian conservation, as an alternate therapeutic option, based upon evidence that extrauterine serous carcinoma may to a significant degree arise from the tubal epithelium rather than the ovarian cortex.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Removal of the adnexae significantly reduces the risk of ovarian cancer among the cohort of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease. However, the decision of whether or not to remove the adnexae when planning surgery should take into account other factors that may affect the risk of adnexal malignancy, including family history and BRCA mutation status, as well as other patient comorbidities.

Andrew W. Menzin, MD

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include your name, city and state.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

The decision-making surrounding gynecologic surgery for benign disease is increasingly complex. Patients and their physicians must balance the potential benefits of salpingo-oophorectomy against possible adverse consequence as they consider various health goals, including longevity, cancer risk, and quality of life.

Chan and colleagues add important data to our understanding of this equation. Analyzing a large cohort of patients from Kaiser Permanente Northern California who underwent hysterectomy for benign disease, they found that removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries significantly reduced the risk of developing ovarian cancer. The incidence of ovarian cancer per 100,000 person-years was 26.2 for women undergoing hysterectomy alone (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–37.0), 17.5 for hysterectomy with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0–39.1), and 1.7 for hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.4–3.0).

The hazard ratio (HR) for ovarian cancer was 0.58 for women undergoing unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.18–1.90) and 0.12 for women undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.05–0.28), compared with women undergoing hysterectomy alone.

Notable strengths of the analysis include the large size of the study population and the duration of patient follow-up (18 years). The authors acknowledge several limitations of the study, including the lack of data on BRCA mutation status and family history of cancer, as well as several other demographic data points possibly relevant to a risk of developing adnexal or peritoneal malignancy.

Related article: What is the gynecologist’s role in the care of BRCA previvors? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2013)

Keep these findings in context

As the authors discuss, this report should be considered in the context of other work suggesting that the lower mortality rate associated with ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease arises mostly from a protective effect against cardiovascular disease (CVD)—perhaps from subclinical hormone production following menopause. Given that CVD remains the leading cause of death among American women, an individualized assessment of risk is necessary when planning the extent of surgery in this circumstance.

Related article: Oophorectomy or salpingectomy—which makes more sense? William H. Parker, MD (March 2014)

It also is interesting to consider the authors’ finding of a notable but statistically insignificant decrease in the risk of ovarian cancer associated with removal of only one tube and ovary. However, recognizing the possible limitations of their demographic information on this point, they suggest that this may be an area for further investigation, which would necessarily include characterization of the trends in the laterality of adnexal cancers. The preservation of hormonal function makes this an interesting option to consider.

We also need to further investigate the role of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, with ovarian conservation, as an alternate therapeutic option, based upon evidence that extrauterine serous carcinoma may to a significant degree arise from the tubal epithelium rather than the ovarian cortex.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Removal of the adnexae significantly reduces the risk of ovarian cancer among the cohort of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease. However, the decision of whether or not to remove the adnexae when planning surgery should take into account other factors that may affect the risk of adnexal malignancy, including family history and BRCA mutation status, as well as other patient comorbidities.

Andrew W. Menzin, MD

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include your name, city and state.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

The decision-making surrounding gynecologic surgery for benign disease is increasingly complex. Patients and their physicians must balance the potential benefits of salpingo-oophorectomy against possible adverse consequence as they consider various health goals, including longevity, cancer risk, and quality of life.

Chan and colleagues add important data to our understanding of this equation. Analyzing a large cohort of patients from Kaiser Permanente Northern California who underwent hysterectomy for benign disease, they found that removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries significantly reduced the risk of developing ovarian cancer. The incidence of ovarian cancer per 100,000 person-years was 26.2 for women undergoing hysterectomy alone (95% confidence interval [CI], 15.5–37.0), 17.5 for hysterectomy with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0–39.1), and 1.7 for hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.4–3.0).

The hazard ratio (HR) for ovarian cancer was 0.58 for women undergoing unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.18–1.90) and 0.12 for women undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (95% CI, 0.05–0.28), compared with women undergoing hysterectomy alone.

Notable strengths of the analysis include the large size of the study population and the duration of patient follow-up (18 years). The authors acknowledge several limitations of the study, including the lack of data on BRCA mutation status and family history of cancer, as well as several other demographic data points possibly relevant to a risk of developing adnexal or peritoneal malignancy.

Related article: What is the gynecologist’s role in the care of BRCA previvors? Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2013)

Keep these findings in context

As the authors discuss, this report should be considered in the context of other work suggesting that the lower mortality rate associated with ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease arises mostly from a protective effect against cardiovascular disease (CVD)—perhaps from subclinical hormone production following menopause. Given that CVD remains the leading cause of death among American women, an individualized assessment of risk is necessary when planning the extent of surgery in this circumstance.

Related article: Oophorectomy or salpingectomy—which makes more sense? William H. Parker, MD (March 2014)

It also is interesting to consider the authors’ finding of a notable but statistically insignificant decrease in the risk of ovarian cancer associated with removal of only one tube and ovary. However, recognizing the possible limitations of their demographic information on this point, they suggest that this may be an area for further investigation, which would necessarily include characterization of the trends in the laterality of adnexal cancers. The preservation of hormonal function makes this an interesting option to consider.

We also need to further investigate the role of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, with ovarian conservation, as an alternate therapeutic option, based upon evidence that extrauterine serous carcinoma may to a significant degree arise from the tubal epithelium rather than the ovarian cortex.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Removal of the adnexae significantly reduces the risk of ovarian cancer among the cohort of women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease. However, the decision of whether or not to remove the adnexae when planning surgery should take into account other factors that may affect the risk of adnexal malignancy, including family history and BRCA mutation status, as well as other patient comorbidities.

Andrew W. Menzin, MD

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com Please include your name, city and state.

Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

Your surgical toolbox should include topical hemostatic agents—here is why

Vessel-sealing devices and hemostatic adjuvants are expanding the surgical armamentarium. These products provide a spectrum of alternatives that can serve you and your surgical patient well when traditional techniques for obtaining hemostasis fail to provide a satisfactory result. (Keep in mind, however, that technology is no substitute for excellent technique!)

In this article, we highlight three common scenarios in which topical hemostatic agents may be useful during gynecologic surgery. In addition, in the sidebar, five surgeons describe the hemostatic products they rely on most often—and tell why.

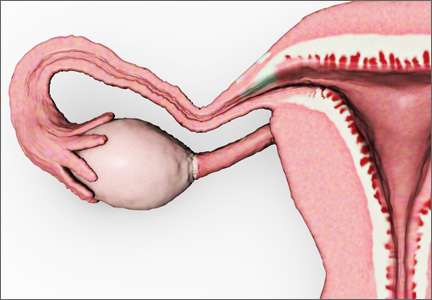

Following hysterectomy, persistent oozing along the anterior vaginal margin, distal to the cuff and adjacent to the site of bladder mobilization, may be managed with the aid of a topical hemostatic agent—in this case, a fibrin sealant.

When the site of bleeding is difficult to reach

CASE 1: Oozing at the site of bladder mobilization

You perform total hysterectomy in a 44-year-old woman who has uterine fibroids. After the procedure, you notice persistent oozing along the anterior vaginal margin, distal to the cuff and adjacent to where the bladder was mobilized.

How do you manage the oozing?

Wide mobilization of the bladder is a vital step in the safe performance of hysterectomy. Adhesions may complicate the process if the patient has had previous abdominal surgery, infection, or inflammation. Following mobilization of the bladder and removal of the uterus, bleeding may be visible along the adventitia of the posterior bladder wall or along the anterior surface of the vagina, distal to the cuff, as it is in this case (see the illustration).

Judicious application of an energy source is an option, but thermal injury to the bladder is a concern. A good alternative is proper placement of a hemostatic suture, but it can sometimes be difficult to avoid incorporating the bladder or injuring or obstructing the nearby ureter.

In this case, the location of the bleeding deep in the operative field poses a challenge, because of limited exposure and the proximity of the bladder and ureters. Virtually any hemostatic agent would work well in this circumstance (TABLE). For example, a flowable agent or fibrin sealant could be thoroughly applied to the area during a minimally invasive or open procedure and would naturally conform to the irregularities in the tissue, particularly the junction between the vagina and bladder flap.

A pliable product such as Surgicel Nu-Knit or Fibrillar would also work well in these circumstances, although successful application during laparoscopy may depend on the size of the trocar. For example, Nu-Knit would require trimming to a size suitable for passage through a trocar, made easier by moistening with saline. The weave of Fibrillar makes it more challenging to pass, intact, through a trocar; rolling the material into a cylindrical shape may reduce its diameter and allow it to pass more easily.

CASE 1: Resolved

You apply a fibrin sealant to the site of bleeding, and the oozing abates. Once complete hemostasis is ensured, you conclude the surgery and transfer the patient to recovery, where she does well.

Profiles in hemostasis: Strengths and weaknesses of topical agent

| Agent (brands) | Composition | Forms available | Mechanism of action | Advantages | Caveats | Duration | Relative cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical agents | |||||||

| Gelatin matrix (Gelfoam, Gelfilm, Surgifoam) | Porcine- derived collagen | Sponge, film, powder | Provides physical matrix for clot formation | Non-antigenic; neutral pH; may be used with thrombin | Material expansion may cause compression; Not for use in closed spaces or near nerve structures | 4–6 weeks | $ |

| Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel Fibrillar, Surgicel Nu-Knit) | Wood pulp | Mesh or packed fibers | Provides physical matrix for clot formation; acidic pH causes hemolysis and local clot formation | Pliable, easy to place through laparoscope; acidic pH has antimicrobial effect | Works best in a dry field. Acidic pH inactivates biologic agents, such as thrombin, and may increase inflammation. Avoid using excess material. | 2–4 weeks | $ |

| Microfibrillar collagen (Avitene, Instat, Helitene Helistat) | Bovine-derived collagen | Powder, non-woven sheet, sponge | Absorbable acid salt. Provides physical scaffold for platelet activation and clot initiation. | Sheet form may be passed through laparoscope; minimal expansion | Rare allergic reactions reported; may contribute to granuloma formation | 8–12 weeks | $$ |

| Biologically active agents | |||||||

| Topical thrombin (Thrombin-JMI, Recothrom, Evithrom, rh Thrombin) | Bovine, human, or recombinant | Liquid | Promotes conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin | May be combined effectively with physical agents of neutral pH; recombinant human thrombin will be available in the near future | Risk of blood-borne infection with non-recombinant human thrombin; risk of anaphylaxis and antibody formation with bovine thrombin | N/A | $$ |

| Hemostatic matrix (Floseal, Surgiflo) | Thrombin plus gelatin | Foam | Gelatin granules provide expansion and compression while thrombin initiates clot formation | May be used in areas of small arterial bleeding | Requires contact with blood | 6–8 weeks | $$$ |

| Fibrin sealants (Evicel, Tisseel, Crosseal) | Human | Liquid | Combination of fibrinogen and thrombin causes cleavage of fibrinogen to fibrin and resultant clot initiation | Fast-acting; hemostatic and adhesive properties; works well for diffusely oozing surfaces | Contraindicated in patients who have a history of anaphylactic reaction to serum-derived products or IgA deficiency | 10–14 days | $$$ |

| * Median cost for use in one case Key: $=inexpensive; $$=moderately expensive; $$$=expensive | |||||||

Controlling bleeding without injuring underlying tissue

CASE 2: After adhesiolysis, bleeding at multiple sites

You perform adnexectomy on a 47-year-old woman who has a large (7 to 8 cm), benign ovarian mass. As you operate, you discover that the lesion is adherent to the sigmoid mesentery and the posterior aspect of the uterus; it is also adherent to the pelvic sidewall, directly along the course of the ureter. Although you are able to release the various adhesive attachments, persistent bleeding is noted at multiple pinpoint areas along the mesentery, uterine serosa, and pelvic sidewall, even after the application of direct pressure.

What do you do next?

Although cautery can be used liberally on the uterus, its application to mesentery carries a risk of injury to the mesenteric vessels and bowel wall. Caution is advised when you are attempting to control bleeding on the peritoneum overlying the ureter, whether you are using suture ligature or an energy source. Ideally, you should identify the ureter using a retroperitoneal approach and mobilize it laterally before employing any of these techniques.

There are several potential approaches to the bleeding described in Case 2, all of them involving hemostatic adjuvants. The first decision you need to make, however, is whether to address each region separately or all sites in unison. If you opt to address them together—either during an open procedure or laparoscopy—a fibrin sealant (e.g., Evicel, Tisseel) is one option. It can be applied using a dripping technique or aerosolization, either of which allows for broad application of a thin film of the agent. The limitation of this approach is the volume of agent required to resolve the bleeding, with a potential need for multiple doses to completely coat the area.

Because fibrin sealants function independently of the patient’s coagulation cascade, they are particularly useful in the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and other coagulopathies that might limit the effectiveness of preparations that require the patient’s own serum.

An alternative approach to Case 2 is to apply an oxidized regenerated cellulose (ORC) derivative directly to the affected areas. Various forms are available (e.g., Surgicel Fibrillar, Surgicel Nu-Knit). These ORC products can be cut and customized to the area in need of hemostasis, allowing each site to be addressed individually. These agents typically remain adherent after they are applied due to the nature of the interaction between the product, blood, and tissue.

A liquid or foam hemostatic agent (e.g., Surgiflo, Floseal, topical thrombin) could also be employed in this case, but application can be a challenge on a large area with a heterogeneous topography because of the tendency of such agents to migrate under the force of gravity, pooling away from the source of bleeding.

Is combining agents a good idea?

Although they are not typically approved for use in combination, sequential application of hemostatic agents may be considered when bleeding persists.

All hemostatic agents work best in combination with the application of pressure. It usually is advisable to use moist gauze for this purpose because it can be lifted away without significant adherence to the underlying hemostatic complex, avoiding clot

disruption.

CASE 2: Resolved

You opt to use an ORC product, customizing it to fit each bleeding site, and apply direct pressure. When hemostasis has been achieved at all sites, you complete the operation. The patient has an uneventful postoperative course.

Protect structures along the pelvic sidewall

CASE 3: When the application of pressure isn’t enough

While performing a left salpingo-oophorectomy for a 12-cm ovarian lesion, you use a retroperitoneal approach to identify the structures along the pelvic sidewall. During identification of the ureter, you encounter bleeding from a small vessel in the adjacent fatty areolar tissue. After a period of observation, during which you apply pressure to the area of concern, bleeding persists.

What hemostatic agent do you employ to stop it?

The careful application of steady pressure is often enough to safely control bleeding in the area of the pelvic sidewall. In the event that pressure alone fails to resolve the bleeding, however, it is critical to choose a remedy that avoids injuring the ureter, iliac vessels, and infundibulopelvic ligament. Wide exposure of the space may allow for direct identification of the point of bleeding and precise application of cautery, a hemoclip, or a tie. When this approach is not feasible, other solutions must be sought.

When traditional hemostatic techniques fail in delicate anatomic sites, such as the periureteral area, hemostatic agents are an effective option that can minimize the risk of injury to surrounding vital structures. The contour of the space calls for a product that can intercalate, such as a foam, sealant, or Surgicel Fibrillar. Direct, precise application to the point of bleeding is critical, and the “bunching up” of a more rigid and bulky agent may limit its application to the area of concern. Use of a moist gauze to apply direct pressure after application of the agent will increase the likelihood of success.

CASE 3: Resolved

You decide to apply a foam hemostatic agent because of its ability to conform to the irregular space. You also continue to apply gentle pressure to the point of bleeding, using a moist gauze. Within minutes, hemostasis is achieved. You are then able to finish the operation.

Other variables to consider

As these three cases illustrate, the use of hemostatic agents to control surgical bleeding requires an individualized approach. The site and amount of bleeding, as well as the patient’s hemodynamic and coagulation status, are key variables to be considered when selecting an agent.

For instance, because of their components, fibrin sealants can function independently of the patient’s coagulation status. ORC products provide a matrix that facilitates platelet aggregration and may be less effective when anti-platelet agents have been used.

It is also appropriate for the surgeon to be familiar with the relative cost of the agents available at his or her institution. In particular, when several agents may be equally effective in a particular set of circumstances, cost may be the determining factor.

Availability of these agents varies from one institution to the next; as a result, it can be challenging to maintain familiarity with all of the products in the marketplace. Having access to a diverse, readily available set of “go to” agents is critical to ensure rapid application in a clinical setting.

The surgeon’s preference also is important, particularly in regard to the ease of preparation and handling. Some agents may not be as suitable for minimally invasive procedures (see TABLE). For others, special laparoscopic applicators are available.

When using a hemostatic agent, it pays to consider the duration of its effect in the surgical site. Both the quantity of the agent that is applied and characteristics of the local operative site influence how quickly the agent degrades. Keep this in mind when imaging studies are planned for the early postoperative period. An ORC preparation, for example, may appear with small pockets of air that resemble an abscess. Effective communication with the radiology team is critical to avoid the misinterpretation of findings.

Curious to discover the preferences and practices of surgeons likely to utilize topical hemostatic agents, OBG Management polled several experienced and expert surgeons, including members of the journal’s Board of Editors and Virtual Board of Editors. Their diverse responses offer a snapshot of gynecologic surgical practice in 2012—but all agree that hemostatic products are no substitute for sound surgical technique.

JANELLE YATES, SENIOR EDITOR

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Recommended reading

Achneck HE, Sileshi B, Jamiolkowski RM, et al. A comprehensive review of topical hemostatic agents: efficacy and recommendations for use. Ann Surg. 2010;251(2):217-228.

Chapman WC, Singla N, Genyk Y, et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind comparative study of the efficacy and safety of topical recombinant human thrombin and bovine thrombin in surgical hemostasis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(2):256-265.

Holub Z, Jabor A. Laparoscopic management of bleeding after laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. JSLS. 2004;8(3):235-238.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(3):271-275.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Topical oxidized cellulose for tubal hemorrhage hemostasis during laparoscopic sterilization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82(2):221-222.

Vessel-sealing devices and hemostatic adjuvants are expanding the surgical armamentarium. These products provide a spectrum of alternatives that can serve you and your surgical patient well when traditional techniques for obtaining hemostasis fail to provide a satisfactory result. (Keep in mind, however, that technology is no substitute for excellent technique!)

In this article, we highlight three common scenarios in which topical hemostatic agents may be useful during gynecologic surgery. In addition, in the sidebar, five surgeons describe the hemostatic products they rely on most often—and tell why.

Following hysterectomy, persistent oozing along the anterior vaginal margin, distal to the cuff and adjacent to the site of bladder mobilization, may be managed with the aid of a topical hemostatic agent—in this case, a fibrin sealant.

When the site of bleeding is difficult to reach

CASE 1: Oozing at the site of bladder mobilization

You perform total hysterectomy in a 44-year-old woman who has uterine fibroids. After the procedure, you notice persistent oozing along the anterior vaginal margin, distal to the cuff and adjacent to where the bladder was mobilized.

How do you manage the oozing?

Wide mobilization of the bladder is a vital step in the safe performance of hysterectomy. Adhesions may complicate the process if the patient has had previous abdominal surgery, infection, or inflammation. Following mobilization of the bladder and removal of the uterus, bleeding may be visible along the adventitia of the posterior bladder wall or along the anterior surface of the vagina, distal to the cuff, as it is in this case (see the illustration).

Judicious application of an energy source is an option, but thermal injury to the bladder is a concern. A good alternative is proper placement of a hemostatic suture, but it can sometimes be difficult to avoid incorporating the bladder or injuring or obstructing the nearby ureter.

In this case, the location of the bleeding deep in the operative field poses a challenge, because of limited exposure and the proximity of the bladder and ureters. Virtually any hemostatic agent would work well in this circumstance (TABLE). For example, a flowable agent or fibrin sealant could be thoroughly applied to the area during a minimally invasive or open procedure and would naturally conform to the irregularities in the tissue, particularly the junction between the vagina and bladder flap.

A pliable product such as Surgicel Nu-Knit or Fibrillar would also work well in these circumstances, although successful application during laparoscopy may depend on the size of the trocar. For example, Nu-Knit would require trimming to a size suitable for passage through a trocar, made easier by moistening with saline. The weave of Fibrillar makes it more challenging to pass, intact, through a trocar; rolling the material into a cylindrical shape may reduce its diameter and allow it to pass more easily.

CASE 1: Resolved

You apply a fibrin sealant to the site of bleeding, and the oozing abates. Once complete hemostasis is ensured, you conclude the surgery and transfer the patient to recovery, where she does well.

Profiles in hemostasis: Strengths and weaknesses of topical agent

| Agent (brands) | Composition | Forms available | Mechanism of action | Advantages | Caveats | Duration | Relative cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical agents | |||||||

| Gelatin matrix (Gelfoam, Gelfilm, Surgifoam) | Porcine- derived collagen | Sponge, film, powder | Provides physical matrix for clot formation | Non-antigenic; neutral pH; may be used with thrombin | Material expansion may cause compression; Not for use in closed spaces or near nerve structures | 4–6 weeks | $ |

| Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel Fibrillar, Surgicel Nu-Knit) | Wood pulp | Mesh or packed fibers | Provides physical matrix for clot formation; acidic pH causes hemolysis and local clot formation | Pliable, easy to place through laparoscope; acidic pH has antimicrobial effect | Works best in a dry field. Acidic pH inactivates biologic agents, such as thrombin, and may increase inflammation. Avoid using excess material. | 2–4 weeks | $ |

| Microfibrillar collagen (Avitene, Instat, Helitene Helistat) | Bovine-derived collagen | Powder, non-woven sheet, sponge | Absorbable acid salt. Provides physical scaffold for platelet activation and clot initiation. | Sheet form may be passed through laparoscope; minimal expansion | Rare allergic reactions reported; may contribute to granuloma formation | 8–12 weeks | $$ |

| Biologically active agents | |||||||

| Topical thrombin (Thrombin-JMI, Recothrom, Evithrom, rh Thrombin) | Bovine, human, or recombinant | Liquid | Promotes conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin | May be combined effectively with physical agents of neutral pH; recombinant human thrombin will be available in the near future | Risk of blood-borne infection with non-recombinant human thrombin; risk of anaphylaxis and antibody formation with bovine thrombin | N/A | $$ |

| Hemostatic matrix (Floseal, Surgiflo) | Thrombin plus gelatin | Foam | Gelatin granules provide expansion and compression while thrombin initiates clot formation | May be used in areas of small arterial bleeding | Requires contact with blood | 6–8 weeks | $$$ |

| Fibrin sealants (Evicel, Tisseel, Crosseal) | Human | Liquid | Combination of fibrinogen and thrombin causes cleavage of fibrinogen to fibrin and resultant clot initiation | Fast-acting; hemostatic and adhesive properties; works well for diffusely oozing surfaces | Contraindicated in patients who have a history of anaphylactic reaction to serum-derived products or IgA deficiency | 10–14 days | $$$ |

| * Median cost for use in one case Key: $=inexpensive; $$=moderately expensive; $$$=expensive | |||||||

Controlling bleeding without injuring underlying tissue

CASE 2: After adhesiolysis, bleeding at multiple sites

You perform adnexectomy on a 47-year-old woman who has a large (7 to 8 cm), benign ovarian mass. As you operate, you discover that the lesion is adherent to the sigmoid mesentery and the posterior aspect of the uterus; it is also adherent to the pelvic sidewall, directly along the course of the ureter. Although you are able to release the various adhesive attachments, persistent bleeding is noted at multiple pinpoint areas along the mesentery, uterine serosa, and pelvic sidewall, even after the application of direct pressure.

What do you do next?

Although cautery can be used liberally on the uterus, its application to mesentery carries a risk of injury to the mesenteric vessels and bowel wall. Caution is advised when you are attempting to control bleeding on the peritoneum overlying the ureter, whether you are using suture ligature or an energy source. Ideally, you should identify the ureter using a retroperitoneal approach and mobilize it laterally before employing any of these techniques.

There are several potential approaches to the bleeding described in Case 2, all of them involving hemostatic adjuvants. The first decision you need to make, however, is whether to address each region separately or all sites in unison. If you opt to address them together—either during an open procedure or laparoscopy—a fibrin sealant (e.g., Evicel, Tisseel) is one option. It can be applied using a dripping technique or aerosolization, either of which allows for broad application of a thin film of the agent. The limitation of this approach is the volume of agent required to resolve the bleeding, with a potential need for multiple doses to completely coat the area.

Because fibrin sealants function independently of the patient’s coagulation cascade, they are particularly useful in the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and other coagulopathies that might limit the effectiveness of preparations that require the patient’s own serum.

An alternative approach to Case 2 is to apply an oxidized regenerated cellulose (ORC) derivative directly to the affected areas. Various forms are available (e.g., Surgicel Fibrillar, Surgicel Nu-Knit). These ORC products can be cut and customized to the area in need of hemostasis, allowing each site to be addressed individually. These agents typically remain adherent after they are applied due to the nature of the interaction between the product, blood, and tissue.

A liquid or foam hemostatic agent (e.g., Surgiflo, Floseal, topical thrombin) could also be employed in this case, but application can be a challenge on a large area with a heterogeneous topography because of the tendency of such agents to migrate under the force of gravity, pooling away from the source of bleeding.

Is combining agents a good idea?

Although they are not typically approved for use in combination, sequential application of hemostatic agents may be considered when bleeding persists.

All hemostatic agents work best in combination with the application of pressure. It usually is advisable to use moist gauze for this purpose because it can be lifted away without significant adherence to the underlying hemostatic complex, avoiding clot

disruption.

CASE 2: Resolved

You opt to use an ORC product, customizing it to fit each bleeding site, and apply direct pressure. When hemostasis has been achieved at all sites, you complete the operation. The patient has an uneventful postoperative course.

Protect structures along the pelvic sidewall

CASE 3: When the application of pressure isn’t enough

While performing a left salpingo-oophorectomy for a 12-cm ovarian lesion, you use a retroperitoneal approach to identify the structures along the pelvic sidewall. During identification of the ureter, you encounter bleeding from a small vessel in the adjacent fatty areolar tissue. After a period of observation, during which you apply pressure to the area of concern, bleeding persists.

What hemostatic agent do you employ to stop it?

The careful application of steady pressure is often enough to safely control bleeding in the area of the pelvic sidewall. In the event that pressure alone fails to resolve the bleeding, however, it is critical to choose a remedy that avoids injuring the ureter, iliac vessels, and infundibulopelvic ligament. Wide exposure of the space may allow for direct identification of the point of bleeding and precise application of cautery, a hemoclip, or a tie. When this approach is not feasible, other solutions must be sought.

When traditional hemostatic techniques fail in delicate anatomic sites, such as the periureteral area, hemostatic agents are an effective option that can minimize the risk of injury to surrounding vital structures. The contour of the space calls for a product that can intercalate, such as a foam, sealant, or Surgicel Fibrillar. Direct, precise application to the point of bleeding is critical, and the “bunching up” of a more rigid and bulky agent may limit its application to the area of concern. Use of a moist gauze to apply direct pressure after application of the agent will increase the likelihood of success.

CASE 3: Resolved

You decide to apply a foam hemostatic agent because of its ability to conform to the irregular space. You also continue to apply gentle pressure to the point of bleeding, using a moist gauze. Within minutes, hemostasis is achieved. You are then able to finish the operation.

Other variables to consider

As these three cases illustrate, the use of hemostatic agents to control surgical bleeding requires an individualized approach. The site and amount of bleeding, as well as the patient’s hemodynamic and coagulation status, are key variables to be considered when selecting an agent.

For instance, because of their components, fibrin sealants can function independently of the patient’s coagulation status. ORC products provide a matrix that facilitates platelet aggregration and may be less effective when anti-platelet agents have been used.

It is also appropriate for the surgeon to be familiar with the relative cost of the agents available at his or her institution. In particular, when several agents may be equally effective in a particular set of circumstances, cost may be the determining factor.

Availability of these agents varies from one institution to the next; as a result, it can be challenging to maintain familiarity with all of the products in the marketplace. Having access to a diverse, readily available set of “go to” agents is critical to ensure rapid application in a clinical setting.

The surgeon’s preference also is important, particularly in regard to the ease of preparation and handling. Some agents may not be as suitable for minimally invasive procedures (see TABLE). For others, special laparoscopic applicators are available.

When using a hemostatic agent, it pays to consider the duration of its effect in the surgical site. Both the quantity of the agent that is applied and characteristics of the local operative site influence how quickly the agent degrades. Keep this in mind when imaging studies are planned for the early postoperative period. An ORC preparation, for example, may appear with small pockets of air that resemble an abscess. Effective communication with the radiology team is critical to avoid the misinterpretation of findings.

Curious to discover the preferences and practices of surgeons likely to utilize topical hemostatic agents, OBG Management polled several experienced and expert surgeons, including members of the journal’s Board of Editors and Virtual Board of Editors. Their diverse responses offer a snapshot of gynecologic surgical practice in 2012—but all agree that hemostatic products are no substitute for sound surgical technique.

JANELLE YATES, SENIOR EDITOR

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Vessel-sealing devices and hemostatic adjuvants are expanding the surgical armamentarium. These products provide a spectrum of alternatives that can serve you and your surgical patient well when traditional techniques for obtaining hemostasis fail to provide a satisfactory result. (Keep in mind, however, that technology is no substitute for excellent technique!)

In this article, we highlight three common scenarios in which topical hemostatic agents may be useful during gynecologic surgery. In addition, in the sidebar, five surgeons describe the hemostatic products they rely on most often—and tell why.

Following hysterectomy, persistent oozing along the anterior vaginal margin, distal to the cuff and adjacent to the site of bladder mobilization, may be managed with the aid of a topical hemostatic agent—in this case, a fibrin sealant.

When the site of bleeding is difficult to reach

CASE 1: Oozing at the site of bladder mobilization

You perform total hysterectomy in a 44-year-old woman who has uterine fibroids. After the procedure, you notice persistent oozing along the anterior vaginal margin, distal to the cuff and adjacent to where the bladder was mobilized.

How do you manage the oozing?

Wide mobilization of the bladder is a vital step in the safe performance of hysterectomy. Adhesions may complicate the process if the patient has had previous abdominal surgery, infection, or inflammation. Following mobilization of the bladder and removal of the uterus, bleeding may be visible along the adventitia of the posterior bladder wall or along the anterior surface of the vagina, distal to the cuff, as it is in this case (see the illustration).

Judicious application of an energy source is an option, but thermal injury to the bladder is a concern. A good alternative is proper placement of a hemostatic suture, but it can sometimes be difficult to avoid incorporating the bladder or injuring or obstructing the nearby ureter.

In this case, the location of the bleeding deep in the operative field poses a challenge, because of limited exposure and the proximity of the bladder and ureters. Virtually any hemostatic agent would work well in this circumstance (TABLE). For example, a flowable agent or fibrin sealant could be thoroughly applied to the area during a minimally invasive or open procedure and would naturally conform to the irregularities in the tissue, particularly the junction between the vagina and bladder flap.

A pliable product such as Surgicel Nu-Knit or Fibrillar would also work well in these circumstances, although successful application during laparoscopy may depend on the size of the trocar. For example, Nu-Knit would require trimming to a size suitable for passage through a trocar, made easier by moistening with saline. The weave of Fibrillar makes it more challenging to pass, intact, through a trocar; rolling the material into a cylindrical shape may reduce its diameter and allow it to pass more easily.

CASE 1: Resolved

You apply a fibrin sealant to the site of bleeding, and the oozing abates. Once complete hemostasis is ensured, you conclude the surgery and transfer the patient to recovery, where she does well.

Profiles in hemostasis: Strengths and weaknesses of topical agent

| Agent (brands) | Composition | Forms available | Mechanism of action | Advantages | Caveats | Duration | Relative cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical agents | |||||||

| Gelatin matrix (Gelfoam, Gelfilm, Surgifoam) | Porcine- derived collagen | Sponge, film, powder | Provides physical matrix for clot formation | Non-antigenic; neutral pH; may be used with thrombin | Material expansion may cause compression; Not for use in closed spaces or near nerve structures | 4–6 weeks | $ |

| Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel Fibrillar, Surgicel Nu-Knit) | Wood pulp | Mesh or packed fibers | Provides physical matrix for clot formation; acidic pH causes hemolysis and local clot formation | Pliable, easy to place through laparoscope; acidic pH has antimicrobial effect | Works best in a dry field. Acidic pH inactivates biologic agents, such as thrombin, and may increase inflammation. Avoid using excess material. | 2–4 weeks | $ |

| Microfibrillar collagen (Avitene, Instat, Helitene Helistat) | Bovine-derived collagen | Powder, non-woven sheet, sponge | Absorbable acid salt. Provides physical scaffold for platelet activation and clot initiation. | Sheet form may be passed through laparoscope; minimal expansion | Rare allergic reactions reported; may contribute to granuloma formation | 8–12 weeks | $$ |

| Biologically active agents | |||||||

| Topical thrombin (Thrombin-JMI, Recothrom, Evithrom, rh Thrombin) | Bovine, human, or recombinant | Liquid | Promotes conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin | May be combined effectively with physical agents of neutral pH; recombinant human thrombin will be available in the near future | Risk of blood-borne infection with non-recombinant human thrombin; risk of anaphylaxis and antibody formation with bovine thrombin | N/A | $$ |

| Hemostatic matrix (Floseal, Surgiflo) | Thrombin plus gelatin | Foam | Gelatin granules provide expansion and compression while thrombin initiates clot formation | May be used in areas of small arterial bleeding | Requires contact with blood | 6–8 weeks | $$$ |

| Fibrin sealants (Evicel, Tisseel, Crosseal) | Human | Liquid | Combination of fibrinogen and thrombin causes cleavage of fibrinogen to fibrin and resultant clot initiation | Fast-acting; hemostatic and adhesive properties; works well for diffusely oozing surfaces | Contraindicated in patients who have a history of anaphylactic reaction to serum-derived products or IgA deficiency | 10–14 days | $$$ |

| * Median cost for use in one case Key: $=inexpensive; $$=moderately expensive; $$$=expensive | |||||||

Controlling bleeding without injuring underlying tissue

CASE 2: After adhesiolysis, bleeding at multiple sites

You perform adnexectomy on a 47-year-old woman who has a large (7 to 8 cm), benign ovarian mass. As you operate, you discover that the lesion is adherent to the sigmoid mesentery and the posterior aspect of the uterus; it is also adherent to the pelvic sidewall, directly along the course of the ureter. Although you are able to release the various adhesive attachments, persistent bleeding is noted at multiple pinpoint areas along the mesentery, uterine serosa, and pelvic sidewall, even after the application of direct pressure.

What do you do next?

Although cautery can be used liberally on the uterus, its application to mesentery carries a risk of injury to the mesenteric vessels and bowel wall. Caution is advised when you are attempting to control bleeding on the peritoneum overlying the ureter, whether you are using suture ligature or an energy source. Ideally, you should identify the ureter using a retroperitoneal approach and mobilize it laterally before employing any of these techniques.

There are several potential approaches to the bleeding described in Case 2, all of them involving hemostatic adjuvants. The first decision you need to make, however, is whether to address each region separately or all sites in unison. If you opt to address them together—either during an open procedure or laparoscopy—a fibrin sealant (e.g., Evicel, Tisseel) is one option. It can be applied using a dripping technique or aerosolization, either of which allows for broad application of a thin film of the agent. The limitation of this approach is the volume of agent required to resolve the bleeding, with a potential need for multiple doses to completely coat the area.

Because fibrin sealants function independently of the patient’s coagulation cascade, they are particularly useful in the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and other coagulopathies that might limit the effectiveness of preparations that require the patient’s own serum.

An alternative approach to Case 2 is to apply an oxidized regenerated cellulose (ORC) derivative directly to the affected areas. Various forms are available (e.g., Surgicel Fibrillar, Surgicel Nu-Knit). These ORC products can be cut and customized to the area in need of hemostasis, allowing each site to be addressed individually. These agents typically remain adherent after they are applied due to the nature of the interaction between the product, blood, and tissue.

A liquid or foam hemostatic agent (e.g., Surgiflo, Floseal, topical thrombin) could also be employed in this case, but application can be a challenge on a large area with a heterogeneous topography because of the tendency of such agents to migrate under the force of gravity, pooling away from the source of bleeding.

Is combining agents a good idea?

Although they are not typically approved for use in combination, sequential application of hemostatic agents may be considered when bleeding persists.

All hemostatic agents work best in combination with the application of pressure. It usually is advisable to use moist gauze for this purpose because it can be lifted away without significant adherence to the underlying hemostatic complex, avoiding clot

disruption.

CASE 2: Resolved

You opt to use an ORC product, customizing it to fit each bleeding site, and apply direct pressure. When hemostasis has been achieved at all sites, you complete the operation. The patient has an uneventful postoperative course.

Protect structures along the pelvic sidewall

CASE 3: When the application of pressure isn’t enough

While performing a left salpingo-oophorectomy for a 12-cm ovarian lesion, you use a retroperitoneal approach to identify the structures along the pelvic sidewall. During identification of the ureter, you encounter bleeding from a small vessel in the adjacent fatty areolar tissue. After a period of observation, during which you apply pressure to the area of concern, bleeding persists.

What hemostatic agent do you employ to stop it?

The careful application of steady pressure is often enough to safely control bleeding in the area of the pelvic sidewall. In the event that pressure alone fails to resolve the bleeding, however, it is critical to choose a remedy that avoids injuring the ureter, iliac vessels, and infundibulopelvic ligament. Wide exposure of the space may allow for direct identification of the point of bleeding and precise application of cautery, a hemoclip, or a tie. When this approach is not feasible, other solutions must be sought.

When traditional hemostatic techniques fail in delicate anatomic sites, such as the periureteral area, hemostatic agents are an effective option that can minimize the risk of injury to surrounding vital structures. The contour of the space calls for a product that can intercalate, such as a foam, sealant, or Surgicel Fibrillar. Direct, precise application to the point of bleeding is critical, and the “bunching up” of a more rigid and bulky agent may limit its application to the area of concern. Use of a moist gauze to apply direct pressure after application of the agent will increase the likelihood of success.

CASE 3: Resolved

You decide to apply a foam hemostatic agent because of its ability to conform to the irregular space. You also continue to apply gentle pressure to the point of bleeding, using a moist gauze. Within minutes, hemostasis is achieved. You are then able to finish the operation.

Other variables to consider

As these three cases illustrate, the use of hemostatic agents to control surgical bleeding requires an individualized approach. The site and amount of bleeding, as well as the patient’s hemodynamic and coagulation status, are key variables to be considered when selecting an agent.

For instance, because of their components, fibrin sealants can function independently of the patient’s coagulation status. ORC products provide a matrix that facilitates platelet aggregration and may be less effective when anti-platelet agents have been used.

It is also appropriate for the surgeon to be familiar with the relative cost of the agents available at his or her institution. In particular, when several agents may be equally effective in a particular set of circumstances, cost may be the determining factor.

Availability of these agents varies from one institution to the next; as a result, it can be challenging to maintain familiarity with all of the products in the marketplace. Having access to a diverse, readily available set of “go to” agents is critical to ensure rapid application in a clinical setting.

The surgeon’s preference also is important, particularly in regard to the ease of preparation and handling. Some agents may not be as suitable for minimally invasive procedures (see TABLE). For others, special laparoscopic applicators are available.

When using a hemostatic agent, it pays to consider the duration of its effect in the surgical site. Both the quantity of the agent that is applied and characteristics of the local operative site influence how quickly the agent degrades. Keep this in mind when imaging studies are planned for the early postoperative period. An ORC preparation, for example, may appear with small pockets of air that resemble an abscess. Effective communication with the radiology team is critical to avoid the misinterpretation of findings.

Curious to discover the preferences and practices of surgeons likely to utilize topical hemostatic agents, OBG Management polled several experienced and expert surgeons, including members of the journal’s Board of Editors and Virtual Board of Editors. Their diverse responses offer a snapshot of gynecologic surgical practice in 2012—but all agree that hemostatic products are no substitute for sound surgical technique.

JANELLE YATES, SENIOR EDITOR

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Recommended reading

Achneck HE, Sileshi B, Jamiolkowski RM, et al. A comprehensive review of topical hemostatic agents: efficacy and recommendations for use. Ann Surg. 2010;251(2):217-228.

Chapman WC, Singla N, Genyk Y, et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind comparative study of the efficacy and safety of topical recombinant human thrombin and bovine thrombin in surgical hemostasis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(2):256-265.

Holub Z, Jabor A. Laparoscopic management of bleeding after laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. JSLS. 2004;8(3):235-238.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(3):271-275.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Topical oxidized cellulose for tubal hemorrhage hemostasis during laparoscopic sterilization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82(2):221-222.

Recommended reading

Achneck HE, Sileshi B, Jamiolkowski RM, et al. A comprehensive review of topical hemostatic agents: efficacy and recommendations for use. Ann Surg. 2010;251(2):217-228.

Chapman WC, Singla N, Genyk Y, et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind comparative study of the efficacy and safety of topical recombinant human thrombin and bovine thrombin in surgical hemostasis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(2):256-265.

Holub Z, Jabor A. Laparoscopic management of bleeding after laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. JSLS. 2004;8(3):235-238.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(3):271-275.

Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Topical oxidized cellulose for tubal hemorrhage hemostasis during laparoscopic sterilization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82(2):221-222.

Q Which preventive strategy is the “best buy” for women with BRCA1/2 mutations?

Expert Commentary

The significance of hereditary predisposition to cancer is now widely understood. Although this predisposition is responsible for only 5% to 10% of the breast and ovarian cancers that occur each year, it offers the potential for prevention and early diagnosis. This study further validates the utility of risk-reducing surgery—not just from an individual patient’s point of view, but also from a public health and healthcare financing perspective.

Newer data shed light on age-specific incidence

This study benefited from fairly recent data on the age-specific incidence of breast and ovarian cancer in women with germline mutations.1 Thus, the 2 surgical options and chemoprevention could be more accurately compared with surveillance to determine the most economical and effective approach. Surveillance consisted of annual mammography; breast ultrasonography if necessary; clinical breast examination; and semiannual gynecologic examinations that included pelvic examination, ultrasonography, and CA-125 studies.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Anderson and colleagues are to be commended for a well-planned and well-executed study. All modeling studies are limited by their assumptions, as the authors observed, and it appears they went to great lengths to optimize their parameters.

I would take issue with only 2 points. First, the authors stated that “BRCA-positive women who develop cancer would have the same conditional probability of death as women with cancer in the general population.” Several groups have reported better survival among women with BRCA mutations who develop advanced ovarian cancer than among matched controls whose disease occurred on a sporadic basis.2,3

The authors also assumed that women at age 35 who were given estrogen therapy until age 50 after prophylactic oophorectomy had no heightened risk for breast cancer, other than the risk already conferred by BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. However, in a report cited by the authors, Rebbeck et al4 described a decrease in the risk of breast cancer among these women—a decrease that hormone therapy did not alter.

Younger women benefited most

Not surprisingly, cost-effectiveness varied with age, with younger women benefiting the most from the preventive strategies.

A dislike of prophylactic mastectomy

Because women are reluctant to undergo prophylactic mastectomy, even when a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation is present, the findings were adjusted for quality of life, which negated the greater cost-effectiveness of surgical strategies that included mastectomy.

Choice of preventive option should involve both patient and physician

Ultimately, a risk-reducing surgical strategy should be chosen by the patient after a thorough review with her physician of the options and their risks and benefits. However, as this report concludes, “Any primary prevention strategy would be cost-effective or cost-saving compared with surveillance.”

1. King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2003;302:643-646.

2. Rubin SC, Benjamin I, Behbakht K, et al. Clinical and pathological features of ovarian cancer in women with germ-line mutations of BRCA. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1413-1416.

3. Cass I, Baldwin RL, Varkey T, Moslehi R, Narod SA, Karlan BY. Improved survival in women with BRCA-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2187-2195.

4. Rebbeck TR, Levin AM, Eisen A, et al. Breast cancer risk after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1475-1479.

Expert Commentary

The significance of hereditary predisposition to cancer is now widely understood. Although this predisposition is responsible for only 5% to 10% of the breast and ovarian cancers that occur each year, it offers the potential for prevention and early diagnosis. This study further validates the utility of risk-reducing surgery—not just from an individual patient’s point of view, but also from a public health and healthcare financing perspective.

Newer data shed light on age-specific incidence

This study benefited from fairly recent data on the age-specific incidence of breast and ovarian cancer in women with germline mutations.1 Thus, the 2 surgical options and chemoprevention could be more accurately compared with surveillance to determine the most economical and effective approach. Surveillance consisted of annual mammography; breast ultrasonography if necessary; clinical breast examination; and semiannual gynecologic examinations that included pelvic examination, ultrasonography, and CA-125 studies.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Anderson and colleagues are to be commended for a well-planned and well-executed study. All modeling studies are limited by their assumptions, as the authors observed, and it appears they went to great lengths to optimize their parameters.

I would take issue with only 2 points. First, the authors stated that “BRCA-positive women who develop cancer would have the same conditional probability of death as women with cancer in the general population.” Several groups have reported better survival among women with BRCA mutations who develop advanced ovarian cancer than among matched controls whose disease occurred on a sporadic basis.2,3

The authors also assumed that women at age 35 who were given estrogen therapy until age 50 after prophylactic oophorectomy had no heightened risk for breast cancer, other than the risk already conferred by BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. However, in a report cited by the authors, Rebbeck et al4 described a decrease in the risk of breast cancer among these women—a decrease that hormone therapy did not alter.

Younger women benefited most

Not surprisingly, cost-effectiveness varied with age, with younger women benefiting the most from the preventive strategies.

A dislike of prophylactic mastectomy

Because women are reluctant to undergo prophylactic mastectomy, even when a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation is present, the findings were adjusted for quality of life, which negated the greater cost-effectiveness of surgical strategies that included mastectomy.

Choice of preventive option should involve both patient and physician

Ultimately, a risk-reducing surgical strategy should be chosen by the patient after a thorough review with her physician of the options and their risks and benefits. However, as this report concludes, “Any primary prevention strategy would be cost-effective or cost-saving compared with surveillance.”

Expert Commentary

The significance of hereditary predisposition to cancer is now widely understood. Although this predisposition is responsible for only 5% to 10% of the breast and ovarian cancers that occur each year, it offers the potential for prevention and early diagnosis. This study further validates the utility of risk-reducing surgery—not just from an individual patient’s point of view, but also from a public health and healthcare financing perspective.

Newer data shed light on age-specific incidence

This study benefited from fairly recent data on the age-specific incidence of breast and ovarian cancer in women with germline mutations.1 Thus, the 2 surgical options and chemoprevention could be more accurately compared with surveillance to determine the most economical and effective approach. Surveillance consisted of annual mammography; breast ultrasonography if necessary; clinical breast examination; and semiannual gynecologic examinations that included pelvic examination, ultrasonography, and CA-125 studies.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Anderson and colleagues are to be commended for a well-planned and well-executed study. All modeling studies are limited by their assumptions, as the authors observed, and it appears they went to great lengths to optimize their parameters.

I would take issue with only 2 points. First, the authors stated that “BRCA-positive women who develop cancer would have the same conditional probability of death as women with cancer in the general population.” Several groups have reported better survival among women with BRCA mutations who develop advanced ovarian cancer than among matched controls whose disease occurred on a sporadic basis.2,3

The authors also assumed that women at age 35 who were given estrogen therapy until age 50 after prophylactic oophorectomy had no heightened risk for breast cancer, other than the risk already conferred by BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. However, in a report cited by the authors, Rebbeck et al4 described a decrease in the risk of breast cancer among these women—a decrease that hormone therapy did not alter.

Younger women benefited most

Not surprisingly, cost-effectiveness varied with age, with younger women benefiting the most from the preventive strategies.

A dislike of prophylactic mastectomy

Because women are reluctant to undergo prophylactic mastectomy, even when a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation is present, the findings were adjusted for quality of life, which negated the greater cost-effectiveness of surgical strategies that included mastectomy.

Choice of preventive option should involve both patient and physician

Ultimately, a risk-reducing surgical strategy should be chosen by the patient after a thorough review with her physician of the options and their risks and benefits. However, as this report concludes, “Any primary prevention strategy would be cost-effective or cost-saving compared with surveillance.”

1. King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2003;302:643-646.

2. Rubin SC, Benjamin I, Behbakht K, et al. Clinical and pathological features of ovarian cancer in women with germ-line mutations of BRCA. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1413-1416.

3. Cass I, Baldwin RL, Varkey T, Moslehi R, Narod SA, Karlan BY. Improved survival in women with BRCA-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2187-2195.

4. Rebbeck TR, Levin AM, Eisen A, et al. Breast cancer risk after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1475-1479.

1. King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2003;302:643-646.

2. Rubin SC, Benjamin I, Behbakht K, et al. Clinical and pathological features of ovarian cancer in women with germ-line mutations of BRCA. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1413-1416.

3. Cass I, Baldwin RL, Varkey T, Moslehi R, Narod SA, Karlan BY. Improved survival in women with BRCA-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2187-2195.

4. Rebbeck TR, Levin AM, Eisen A, et al. Breast cancer risk after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1475-1479.

Q Is it better to remove or spare ovaries at hysterectomy?

It only seems that this controversy is coming to the fore for the first time. In reality, it has been hotly debated for decades. One camp favors oophorectomy to prevent ovarian cancer; the other, preservation of the ovaries to reduce the risk of heart disease and hip fracture.

What is the function of the postovulatory ovary?

GUZICK: Some experts recommend conserving the ovaries to reduce the risk of heart disease. Why? The postovulatory ovary continues to produce androgens, which are converted to circulating estrogens. The androgens themselves are said to improve libido (itself a controversial assertion),1 and their conversion to estrogens may reduce the risk of heart disease2 and hip fracture.3

Parker and colleagues used a Markov decision-analysis model to estimate whether, on balance, the ovaries should be removed or conserved during hysterectomy for benign disease in women at least 40 years old. Using this model, ovarian conservation averted enough heart disease and hip fracture cases to more than offset new cases of ovarian and breast cancers.

About half of all women older than 40 will die of heart disease,4 while fewer than 1% will die of ovarian cancer.5 If women undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease are roughly 50 times more likely to die of heart disease than ovarian cancer, then clearly even a small protective effect of ovarian conservation on heart disease will outweigh the potential for ovarian cancer.

For the moment, let’s take the study by Parker and colleagues at face value. Given the high base rate of cardiovascular disease, it is not surprising that oophorectomy markedly diminishes the overall probability of survival at age 80 among women undergoing hysterectomy at age 50 to 54. The authors estimate that oophorectomy reduces this probability from 62% to 54%. Moreover, the estimated impact of oophorectomy on mortality varies by age. This effect is built into the model because of the age-associated increase in the base rate of ovarian cancer mortality and the estimate that the risk of coronary heart disease declines 6% each year oophorectomy is delayed after menopause.6

Significant differences in survival curves between groups of women undergoing ovarian removal or conservation are found between the ages of 40 and 54, and the curves converge after age 65. Thus, Parker and colleagues conclude that “ovarian conservation until age 65 benefits long-term survival.”

Other factors may influence survival

GUZICK: Ovarian conservation reduces hip fracture3 but increases breast cancer, at least up until age 50.6 Such factors are included in the Parker analysis, but the main drivers of the model are heart disease and ovarian cancer. The conceptual framework for the model, and the pattern of the results, are clear strengths of this study.

MENZIN: Parker et al noted that their study did not address the benefits of oophorectomy among women with known or possible hereditary predisposition to ovarian cancer. Nevertheless, being aware of this major risk factor and its relevance to an informed consent discussion of hysterectomy is important, especially given the recognized benefits of risk-reducing surgery in this setting.

For women whose risk of ovarian cancer is equivalent to that of the general population, the decision is more complex. Hysterectomy, even with ovarian conservation, itself appears to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by 10% to 40%—probably because abnormal-appearing ovaries are usually removed at hysterectomy.7,8 The prognosis of ovarian cancer in conserved ovaries appears equivalent to that in women without hysterectomy,9 although several studies suggest that 5% to 15% of ovarian cancers might have been prevented by oophorectomy at the time of prior hysterectomy for benign disease.

Why the Parker findings can’t be taken at face value

GUZICK: The estimated benefit of ovarian conservation in regard to heart disease was based on data acquired between 1976 and 1982 from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS).2 This is problematic for several reasons. First, the relative risk of 2.2 was estimated in the NHS for coronary heart disease events, not deaths.2 It is not clear how Parker et al converted relative risk of events to relative risk of deaths, but apparently the risk estimate for events was applied to a baseline death rate. If so, then, because not all women with a cardiovascular event from 1976 to 1982 died of cardiovascular disease, the effect of oophorectomy is overstated.

Translating event effects to mortality effects is even more problematic when applied to contemporary medical practice. Women at risk of common cardiovascular problems such as hypertension and coronary artery disease now have the benefit of advances in diagnosis (blood pressure monitoring, biochemical markers, endothelial function tests, and coronary imaging) and treatment (eg, statins, antihypertensives, and coronary artery stents), which can reduce the likelihood of both cardiovascular events and deaths.

Finally, the relative risk for oophorectomy is based not on a randomized trial but on the observational, longitudinal NHS study,2 which may have been subject to selection bias. Were women who went against prevailing wisdom and retained their ovaries at the time of hysterectomy the same ones who had a prevention/wellness view of personal health? Did they follow a regimen of personal fitness and nutrition that reduced their risk of heart disease? In such a scenario, not captured by the statistical controls in the study,4 the dual facts of ovarian conservation and reduced heart disease are true but unrelated.

MENZIN: I agree that the modeling used by Parker and colleagues depends on several reference data sets that have their own potential biases and limitations. For example, the authors recognized that “no published data were found for coronary risk when oophorectomy was performed after menopause,” yet their study purportedly demonstrated that the excess mortality associated with oophorectomy between the ages of 50 and 65 years was primarily a result of coronary disease.

The clinical importance of postmenopausal hormone production has not been fully determined. Furthermore, the duration of effective estrogen production in conserved ovaries also can be hard to predict; almost 33% of women experience menopause within 2 years after hysterectomy with ovarian conservation.10

The Parker study focuses on mortality; however, the likelihood of medical or surgical intervention for benign or equivocal adnexal pathology also should be considered, along with the potential complexity of such treatments.

Women feel uninformed about their options

GUZICK: In my judgment, the fate of the ovaries in a woman undergoing hysterectomy for benign disease should be based on a thorough discussion with the patient that takes into account her individual risk profile and the psychological weight she attaches to the various outcomes. Key factors in the risk profile include age; menopausal status; family history of heart disease and breast and ovarian cancer; and biochemical, genetic, or imaging findings related to cancer, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis.

For example, a 45-year-old woman who is lean and normotensive with a favorable lipid profile, and who greatly fears the prospect of ovarian cancer because a friend died of the disease, may choose to have her ovaries removed. Whether this decision is “right” or “wrong” in general is hard to say, but for this patient the decision is acceptable. Her individual risk for cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis can be monitored more carefully and, if necessary, treated effectively early on. She can be given estrogen for vasomotor symptoms.

For postmenopausal women in their early to mid-50s, the situation is murkier, but a blanket recommendation still seems unwarranted. For women in their late 50s and older, although the Parker model shows a “visual” difference between projected survival curves until age 65, it is not clear whether such differences are statistically significant.

MENZIN: A critical point was highlighted in a recent description of interviews with women awaiting hysterectomy. Bhavnani and Clarke11 found that “many women felt inadequately informed about their treatment options and were unaware of important longer-term outcomes of oophorectomy.” Although the work by Parker and colleagues adds another dimension to the counseling of women considering hysterectomy for benign indications, the complexity of that counseling continues to evolve.

Ultimately, the Parker study demonstrates that oophorectomy does not provide a survival benefit over ovarian conservation. This does not mean oophorectomy is always unadvised. Equivalent treatment arms of randomized trials in oncology have demonstrated that quality of life can vary between alternate therapies. Parker and colleagues did not address this critical issue—one I believe to be at the core of every therapeutic decision and informed consent discussion.

In the end, we must individualize the operation to meet the goals and expectations of the patient.

GUZICK: I agree. A one-size-fits-all approach to clinical decision-making is rarely appropriate. The study by Parker et al provides a framework for women to determine which size is best for them.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Guzick DS, Hoeger K. Sex, hormones, and hysterectomies. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:730-731.

2. Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, et al. Menopause and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1105-1110.

3. Melton LJ, 3rd, Khosla S, Malkasian GD, et al. Fracture risk after bilateral oophorectomy in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:900-905.

4. National Cancer Institute, Statistical Research and Applications Branch. DevCan database: SEER 13 incidence and mortality, 2000–2002, released April 2005, based on the November 2004 submission. For more information see: http://srab.cancer.gov/devcan/. Accessed October 13, 2005.

5. American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2005 update. Available at: www.american-heart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=1200026. Accessed October 13, 2005.

6. Shairer C, Persson I, Falkeborn M, Naessen T, Troisi R, Brinton LA. Breast cancer risk associated with gynecologic surgery and indications for such surgery. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:150-154.

7. Parazzini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Luchini L, Mezzopane R. Hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and subsequent ovarian cancer risk. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:363-366.

8. Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, Decarli A, et al. Hysterectomy with or without unilateral oophorectomy and risk of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:586-587.

9. Fine BA, Yazigi R, Risser R. Prognosis of ovarian cancer developing in the residual ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;43:164-166.