User login

Man, 45, With Greasy Rash and Deformed Nails

A 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology office complaining of a pruritic rash on his neck, chest, abdomen, and upper back. The rash had been present since the patient was 20, intermittently flaring and causing severe pruritus. For the past two weeks, it had become increasingly bothersome.

The patient described the rash as “greasy” brown plaques diffusely scattered on his body. The rash on his neck was the most bothersome, and the patient felt an uncontrollable need to scratch that area.

Since it first developed 25 years ago, he had used OTC hydrocortisone cream as needed to treat the rash. Although effective for past flares, the cream provided only minimal relief during the current episode.

The patient’s medical history included brittle nails with a worsening of nail quality in recent years. The family history revealed that the patient’s father and sister were affected by the same type of rash, which developed in adolescence for each of them, as well as brittle nails.

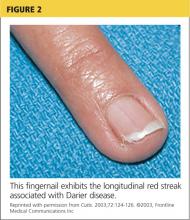

On physical examination, the skin was warm and moist to the touch. Flat, slightly elevated, greasy brown papules were scattered on the chest, abdomen, and upper back, with mild surrounding erythema (see Figure 1). Excoriated lesions were noted on the anterior surface of the neck, with pinpoint bleeding resulting from constant irritation. The patient’s fingernails were deformed, with longitudinal ridges and v-shaped notching of the free margin. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable, and review of systems was negative.

This patient’s symptoms could result from a variety of causes. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition that presents with brown plaques similar to those on the patient’s trunk. Another possible diagnosis is Grover’s disease, a rare disorder also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, in which keratotic plaques appear on the torso and are thought to occur from trauma to sun-damaged skin. An additional consideration is Hailey-Hailey disease, a rare genetic disorder also known as benign familial pemphigus, which is characterized by red-brown plaques located predominantly on flexure surfaces.1 Skin biopsy should be performed for a definitive diagnosis.

Given the family history of a similar rash occurring in first-degree relatives and the distinct physical exam findings, the most likely diagnosis for this patient is keratosis follicularis, also known as Darier disease (DD) or Darier-White disease.

DISCUSSION

Named after Ferdinand-Jean Darier, who discovered this rare genodermatosis, DD is a rare genetic skin disorder caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 12 at position 24,11.1,2 The mutation disrupts the encoding of the enzyme sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2 (SERCA2). This enzyme is important in the transport of calcium ions across the cell membrane, and insufficient amounts lead to a defect in intracellular calcium signaling.2,3

This genetic mutation is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with complete penetrance. DD affects men and women equally, with progressive skin signs of interfamilial and intrafamilial variability.4 Skin manifestations occur from late childhood to early adulthood and are typical during adolescence.4 Acute flare-ups can be triggered by heat, perspiration, sunlight, ultraviolet B exposure, stress, or certain medications (in particular, lithium).2 DD is not contagious.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The characteristics of DD include yellow or brown, rough, firm papules that are frequently crusted. The papules often appear in seborrheic areas of the body, such as the chest, back, ears, nasolabial fold, forehead, scalp, and groin.4 The severity of expression varies from mild, with few lesions, to severe, in which the entire body is covered with disfiguring, macerated plaques emitting a strong odor. On biopsy, the histopathologic findings are typical of dyskeratosis and acantholysis.4

Fingernails (and occasionally toenails) display broad, white or red, somewhat translucent, longitudinal bands accompanied by v-shaped notching1,4,5 (see Figure 2). Such nail changes are diagnostic and occur in 92% to 95% of patients with DD.6 They may, in fact, occur in the absence of cutaneous disease. All nails may be affected, but usually only two to three are involved.6

Although uncommon in DD, white, umbilicated, or cobblestone plaques may be found on intraoral mucous membranes (ie, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, epiglottis, pharyngeal wall, and esophagus); due to confluence, papules may mimic leukoplakia.7 Lesions may also appear on the vulva or rectum.1,5 In severe cases, the salivary glands can become blocked, and the gums can hypertrophy.5

Since epidermal and brain tissue both derive from ectoderm, pathologic processes that affect one organ system may also affect the other.8 Indeed, among patients with DD, neuropsychiatric problems—including epilepsy, learning difficulties, and schizoaffective disorder—are commonly reported.1 To confirm an association between DD and ATP2A2 mutations, Jacobsen and colleagues performed an analysis of 19 unrelated DD patients with neuropsychiatric phenotypes. They discovered evidence to support the gene’s pleiotropic effects in the brain and hypothesized that mutations in the enzyme SERCA2 correlate with these phenotypes, most specifically for mood disorders.9

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Although no cure is currently available for DD, both short- and long-term treatment options are available; the choice should be based on the severity of an individual patient’s signs and symptoms. For mild cases, topical therapy, such as general emollients, corticosteroid ointments, and high sun protection factor sunscreen, is sufficient.1

For moderate cases, topical retinoids, including tretinoin cream, adapalene gel or cream, and tazarotene gel, may be necessary.4 Keratolytics, including salicylic acid in propylene glycol gel, may be used to regulate hyperkeratosis.4 Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, is another option that may restore the down regulation of SERCA2. This can prevent progression of the disease.10

Long-term management includes use of oral retinoid therapy (eg, acitretin), which might reduce the frequency of inflammatory flares.1 Systemic adverse effects from long-term use of oral retinoids are cause for concern, however. Close monitoring along with patient education can limit the occurrence of complications.11

If DD is uncontrolled with medication, dermabrasion and erbium:YAG laser ablation have been used to successfully treat chronic cases.12 Although these treatment options may remove existing lesions, it is important to inform patients that the disease has not been cured, that remission is difficult to attain, and that lesions may recur.

Because viral, bacterial, and fungal superinfections are common and may exacerbate the disease, be sure to check for signs of infection while examining the patient.4 Patients should be advised to avoid hot environments, and if that is not possible, to dress in cool cotton clothing to allow for proper ventilation and avoid the build-up of perspiration. Excessive perspiration along with poor hygiene can contribute to the formation of infections as well as trigger a flare-up. If an infection develops, patients should consult a health care provider.

Keeping the skin well moisturized can alleviate the constant pruritus that many patients experience. Daily sunscreen use is essential to avoid skin irritation caused by the sun, which can trigger an acute flare-up. Patients should be advised to avoid the long-term use of corticosteroid ointment. They should also contact their health care provider before using OTC treatments such as Burow’s solution.

CONCLUSION

A thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the diagnosis of DD. In this particular case, inquiry into family history was the key to proper diagnosis. That information, paired with a thorough physical exam, led to the correct diagnosis of this rare genetic skin disorder. A skin biopsy provided definitive confirmation.

This patient had a mild-to-moderate manifestation of DD. He was prescribed retinoid therapy, and routine follow-up visits were recommended to monitor the efficacy of medical therapy and to screen for secondary infections or neuropsychiatric disorders.

This case illustrates the importance of taking a full history and performing an in-depth physical exam when a patient presents with an unfamiliar complaint. Being thorough reduces the risk of missing a crucial element that can guide the diagnostic process.

REFERENCES

1. Creamer D, Barker J, Kerdel FA. Papular and papulosquamous dermatoses. In: Acute Adult Dermatology: Diagnosis and Management (A Colour Handbook). London, UK: Manson Publishing Ltd; 2011:48.

2. Kelly EB. Darier disease (DAR). In: Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2013:186-187.

3. Klausegger A, Laimer M, Bauer JW. Darier disease. [In German.] Hautarzt. 2013;64:22-25.

4. Ringpfeil F. Dermatologic disorders. In: NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:101.

5. Disorders of keratinization. In: Ostler HB, Maibach HI, Hoke AW, Schwab IR, eds. Diseases of the Eye and Skin: A Color Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:23-34.

6. Baran R, de Berker D, Holzberg M, Thomas L, eds. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and their Management. 4th ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:295-296.

7. Thiagarajan MK, Narasimhan M, Sankarasubramanian A. Darier disease with oral and esophageal involvement: a case report. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:843-846.

8. Medansky RS, Woloshin AA. Darier’s disease: an evaluation of its neuropsychiatric component. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:482-484.

9. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1631-1636.

10. Kamijo M, Nishiyama C, Takagi A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition restores ultraviolet B-induced downregulation of ATP2A2/SERCA2 in keratinocytes: possible therapeutic approach of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition for treatment of Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166: 1017-1022.

11. Brecher AR, Orlow SJ. Oral retinoid therapy for dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:171-182.

12. Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;35:423-427.

A 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology office complaining of a pruritic rash on his neck, chest, abdomen, and upper back. The rash had been present since the patient was 20, intermittently flaring and causing severe pruritus. For the past two weeks, it had become increasingly bothersome.

The patient described the rash as “greasy” brown plaques diffusely scattered on his body. The rash on his neck was the most bothersome, and the patient felt an uncontrollable need to scratch that area.

Since it first developed 25 years ago, he had used OTC hydrocortisone cream as needed to treat the rash. Although effective for past flares, the cream provided only minimal relief during the current episode.

The patient’s medical history included brittle nails with a worsening of nail quality in recent years. The family history revealed that the patient’s father and sister were affected by the same type of rash, which developed in adolescence for each of them, as well as brittle nails.

On physical examination, the skin was warm and moist to the touch. Flat, slightly elevated, greasy brown papules were scattered on the chest, abdomen, and upper back, with mild surrounding erythema (see Figure 1). Excoriated lesions were noted on the anterior surface of the neck, with pinpoint bleeding resulting from constant irritation. The patient’s fingernails were deformed, with longitudinal ridges and v-shaped notching of the free margin. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable, and review of systems was negative.

This patient’s symptoms could result from a variety of causes. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition that presents with brown plaques similar to those on the patient’s trunk. Another possible diagnosis is Grover’s disease, a rare disorder also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, in which keratotic plaques appear on the torso and are thought to occur from trauma to sun-damaged skin. An additional consideration is Hailey-Hailey disease, a rare genetic disorder also known as benign familial pemphigus, which is characterized by red-brown plaques located predominantly on flexure surfaces.1 Skin biopsy should be performed for a definitive diagnosis.

Given the family history of a similar rash occurring in first-degree relatives and the distinct physical exam findings, the most likely diagnosis for this patient is keratosis follicularis, also known as Darier disease (DD) or Darier-White disease.

DISCUSSION

Named after Ferdinand-Jean Darier, who discovered this rare genodermatosis, DD is a rare genetic skin disorder caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 12 at position 24,11.1,2 The mutation disrupts the encoding of the enzyme sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2 (SERCA2). This enzyme is important in the transport of calcium ions across the cell membrane, and insufficient amounts lead to a defect in intracellular calcium signaling.2,3

This genetic mutation is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with complete penetrance. DD affects men and women equally, with progressive skin signs of interfamilial and intrafamilial variability.4 Skin manifestations occur from late childhood to early adulthood and are typical during adolescence.4 Acute flare-ups can be triggered by heat, perspiration, sunlight, ultraviolet B exposure, stress, or certain medications (in particular, lithium).2 DD is not contagious.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The characteristics of DD include yellow or brown, rough, firm papules that are frequently crusted. The papules often appear in seborrheic areas of the body, such as the chest, back, ears, nasolabial fold, forehead, scalp, and groin.4 The severity of expression varies from mild, with few lesions, to severe, in which the entire body is covered with disfiguring, macerated plaques emitting a strong odor. On biopsy, the histopathologic findings are typical of dyskeratosis and acantholysis.4

Fingernails (and occasionally toenails) display broad, white or red, somewhat translucent, longitudinal bands accompanied by v-shaped notching1,4,5 (see Figure 2). Such nail changes are diagnostic and occur in 92% to 95% of patients with DD.6 They may, in fact, occur in the absence of cutaneous disease. All nails may be affected, but usually only two to three are involved.6

Although uncommon in DD, white, umbilicated, or cobblestone plaques may be found on intraoral mucous membranes (ie, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, epiglottis, pharyngeal wall, and esophagus); due to confluence, papules may mimic leukoplakia.7 Lesions may also appear on the vulva or rectum.1,5 In severe cases, the salivary glands can become blocked, and the gums can hypertrophy.5

Since epidermal and brain tissue both derive from ectoderm, pathologic processes that affect one organ system may also affect the other.8 Indeed, among patients with DD, neuropsychiatric problems—including epilepsy, learning difficulties, and schizoaffective disorder—are commonly reported.1 To confirm an association between DD and ATP2A2 mutations, Jacobsen and colleagues performed an analysis of 19 unrelated DD patients with neuropsychiatric phenotypes. They discovered evidence to support the gene’s pleiotropic effects in the brain and hypothesized that mutations in the enzyme SERCA2 correlate with these phenotypes, most specifically for mood disorders.9

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Although no cure is currently available for DD, both short- and long-term treatment options are available; the choice should be based on the severity of an individual patient’s signs and symptoms. For mild cases, topical therapy, such as general emollients, corticosteroid ointments, and high sun protection factor sunscreen, is sufficient.1

For moderate cases, topical retinoids, including tretinoin cream, adapalene gel or cream, and tazarotene gel, may be necessary.4 Keratolytics, including salicylic acid in propylene glycol gel, may be used to regulate hyperkeratosis.4 Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, is another option that may restore the down regulation of SERCA2. This can prevent progression of the disease.10

Long-term management includes use of oral retinoid therapy (eg, acitretin), which might reduce the frequency of inflammatory flares.1 Systemic adverse effects from long-term use of oral retinoids are cause for concern, however. Close monitoring along with patient education can limit the occurrence of complications.11

If DD is uncontrolled with medication, dermabrasion and erbium:YAG laser ablation have been used to successfully treat chronic cases.12 Although these treatment options may remove existing lesions, it is important to inform patients that the disease has not been cured, that remission is difficult to attain, and that lesions may recur.

Because viral, bacterial, and fungal superinfections are common and may exacerbate the disease, be sure to check for signs of infection while examining the patient.4 Patients should be advised to avoid hot environments, and if that is not possible, to dress in cool cotton clothing to allow for proper ventilation and avoid the build-up of perspiration. Excessive perspiration along with poor hygiene can contribute to the formation of infections as well as trigger a flare-up. If an infection develops, patients should consult a health care provider.

Keeping the skin well moisturized can alleviate the constant pruritus that many patients experience. Daily sunscreen use is essential to avoid skin irritation caused by the sun, which can trigger an acute flare-up. Patients should be advised to avoid the long-term use of corticosteroid ointment. They should also contact their health care provider before using OTC treatments such as Burow’s solution.

CONCLUSION

A thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the diagnosis of DD. In this particular case, inquiry into family history was the key to proper diagnosis. That information, paired with a thorough physical exam, led to the correct diagnosis of this rare genetic skin disorder. A skin biopsy provided definitive confirmation.

This patient had a mild-to-moderate manifestation of DD. He was prescribed retinoid therapy, and routine follow-up visits were recommended to monitor the efficacy of medical therapy and to screen for secondary infections or neuropsychiatric disorders.

This case illustrates the importance of taking a full history and performing an in-depth physical exam when a patient presents with an unfamiliar complaint. Being thorough reduces the risk of missing a crucial element that can guide the diagnostic process.

REFERENCES

1. Creamer D, Barker J, Kerdel FA. Papular and papulosquamous dermatoses. In: Acute Adult Dermatology: Diagnosis and Management (A Colour Handbook). London, UK: Manson Publishing Ltd; 2011:48.

2. Kelly EB. Darier disease (DAR). In: Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2013:186-187.

3. Klausegger A, Laimer M, Bauer JW. Darier disease. [In German.] Hautarzt. 2013;64:22-25.

4. Ringpfeil F. Dermatologic disorders. In: NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:101.

5. Disorders of keratinization. In: Ostler HB, Maibach HI, Hoke AW, Schwab IR, eds. Diseases of the Eye and Skin: A Color Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:23-34.

6. Baran R, de Berker D, Holzberg M, Thomas L, eds. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and their Management. 4th ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:295-296.

7. Thiagarajan MK, Narasimhan M, Sankarasubramanian A. Darier disease with oral and esophageal involvement: a case report. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:843-846.

8. Medansky RS, Woloshin AA. Darier’s disease: an evaluation of its neuropsychiatric component. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:482-484.

9. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1631-1636.

10. Kamijo M, Nishiyama C, Takagi A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition restores ultraviolet B-induced downregulation of ATP2A2/SERCA2 in keratinocytes: possible therapeutic approach of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition for treatment of Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166: 1017-1022.

11. Brecher AR, Orlow SJ. Oral retinoid therapy for dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:171-182.

12. Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;35:423-427.

A 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology office complaining of a pruritic rash on his neck, chest, abdomen, and upper back. The rash had been present since the patient was 20, intermittently flaring and causing severe pruritus. For the past two weeks, it had become increasingly bothersome.

The patient described the rash as “greasy” brown plaques diffusely scattered on his body. The rash on his neck was the most bothersome, and the patient felt an uncontrollable need to scratch that area.

Since it first developed 25 years ago, he had used OTC hydrocortisone cream as needed to treat the rash. Although effective for past flares, the cream provided only minimal relief during the current episode.

The patient’s medical history included brittle nails with a worsening of nail quality in recent years. The family history revealed that the patient’s father and sister were affected by the same type of rash, which developed in adolescence for each of them, as well as brittle nails.

On physical examination, the skin was warm and moist to the touch. Flat, slightly elevated, greasy brown papules were scattered on the chest, abdomen, and upper back, with mild surrounding erythema (see Figure 1). Excoriated lesions were noted on the anterior surface of the neck, with pinpoint bleeding resulting from constant irritation. The patient’s fingernails were deformed, with longitudinal ridges and v-shaped notching of the free margin. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable, and review of systems was negative.

This patient’s symptoms could result from a variety of causes. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition that presents with brown plaques similar to those on the patient’s trunk. Another possible diagnosis is Grover’s disease, a rare disorder also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, in which keratotic plaques appear on the torso and are thought to occur from trauma to sun-damaged skin. An additional consideration is Hailey-Hailey disease, a rare genetic disorder also known as benign familial pemphigus, which is characterized by red-brown plaques located predominantly on flexure surfaces.1 Skin biopsy should be performed for a definitive diagnosis.

Given the family history of a similar rash occurring in first-degree relatives and the distinct physical exam findings, the most likely diagnosis for this patient is keratosis follicularis, also known as Darier disease (DD) or Darier-White disease.

DISCUSSION

Named after Ferdinand-Jean Darier, who discovered this rare genodermatosis, DD is a rare genetic skin disorder caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 12 at position 24,11.1,2 The mutation disrupts the encoding of the enzyme sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2 (SERCA2). This enzyme is important in the transport of calcium ions across the cell membrane, and insufficient amounts lead to a defect in intracellular calcium signaling.2,3

This genetic mutation is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with complete penetrance. DD affects men and women equally, with progressive skin signs of interfamilial and intrafamilial variability.4 Skin manifestations occur from late childhood to early adulthood and are typical during adolescence.4 Acute flare-ups can be triggered by heat, perspiration, sunlight, ultraviolet B exposure, stress, or certain medications (in particular, lithium).2 DD is not contagious.2

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The characteristics of DD include yellow or brown, rough, firm papules that are frequently crusted. The papules often appear in seborrheic areas of the body, such as the chest, back, ears, nasolabial fold, forehead, scalp, and groin.4 The severity of expression varies from mild, with few lesions, to severe, in which the entire body is covered with disfiguring, macerated plaques emitting a strong odor. On biopsy, the histopathologic findings are typical of dyskeratosis and acantholysis.4

Fingernails (and occasionally toenails) display broad, white or red, somewhat translucent, longitudinal bands accompanied by v-shaped notching1,4,5 (see Figure 2). Such nail changes are diagnostic and occur in 92% to 95% of patients with DD.6 They may, in fact, occur in the absence of cutaneous disease. All nails may be affected, but usually only two to three are involved.6

Although uncommon in DD, white, umbilicated, or cobblestone plaques may be found on intraoral mucous membranes (ie, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, epiglottis, pharyngeal wall, and esophagus); due to confluence, papules may mimic leukoplakia.7 Lesions may also appear on the vulva or rectum.1,5 In severe cases, the salivary glands can become blocked, and the gums can hypertrophy.5

Since epidermal and brain tissue both derive from ectoderm, pathologic processes that affect one organ system may also affect the other.8 Indeed, among patients with DD, neuropsychiatric problems—including epilepsy, learning difficulties, and schizoaffective disorder—are commonly reported.1 To confirm an association between DD and ATP2A2 mutations, Jacobsen and colleagues performed an analysis of 19 unrelated DD patients with neuropsychiatric phenotypes. They discovered evidence to support the gene’s pleiotropic effects in the brain and hypothesized that mutations in the enzyme SERCA2 correlate with these phenotypes, most specifically for mood disorders.9

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Although no cure is currently available for DD, both short- and long-term treatment options are available; the choice should be based on the severity of an individual patient’s signs and symptoms. For mild cases, topical therapy, such as general emollients, corticosteroid ointments, and high sun protection factor sunscreen, is sufficient.1

For moderate cases, topical retinoids, including tretinoin cream, adapalene gel or cream, and tazarotene gel, may be necessary.4 Keratolytics, including salicylic acid in propylene glycol gel, may be used to regulate hyperkeratosis.4 Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, is another option that may restore the down regulation of SERCA2. This can prevent progression of the disease.10

Long-term management includes use of oral retinoid therapy (eg, acitretin), which might reduce the frequency of inflammatory flares.1 Systemic adverse effects from long-term use of oral retinoids are cause for concern, however. Close monitoring along with patient education can limit the occurrence of complications.11

If DD is uncontrolled with medication, dermabrasion and erbium:YAG laser ablation have been used to successfully treat chronic cases.12 Although these treatment options may remove existing lesions, it is important to inform patients that the disease has not been cured, that remission is difficult to attain, and that lesions may recur.

Because viral, bacterial, and fungal superinfections are common and may exacerbate the disease, be sure to check for signs of infection while examining the patient.4 Patients should be advised to avoid hot environments, and if that is not possible, to dress in cool cotton clothing to allow for proper ventilation and avoid the build-up of perspiration. Excessive perspiration along with poor hygiene can contribute to the formation of infections as well as trigger a flare-up. If an infection develops, patients should consult a health care provider.

Keeping the skin well moisturized can alleviate the constant pruritus that many patients experience. Daily sunscreen use is essential to avoid skin irritation caused by the sun, which can trigger an acute flare-up. Patients should be advised to avoid the long-term use of corticosteroid ointment. They should also contact their health care provider before using OTC treatments such as Burow’s solution.

CONCLUSION

A thorough history and physical exam are crucial in the diagnosis of DD. In this particular case, inquiry into family history was the key to proper diagnosis. That information, paired with a thorough physical exam, led to the correct diagnosis of this rare genetic skin disorder. A skin biopsy provided definitive confirmation.

This patient had a mild-to-moderate manifestation of DD. He was prescribed retinoid therapy, and routine follow-up visits were recommended to monitor the efficacy of medical therapy and to screen for secondary infections or neuropsychiatric disorders.

This case illustrates the importance of taking a full history and performing an in-depth physical exam when a patient presents with an unfamiliar complaint. Being thorough reduces the risk of missing a crucial element that can guide the diagnostic process.

REFERENCES

1. Creamer D, Barker J, Kerdel FA. Papular and papulosquamous dermatoses. In: Acute Adult Dermatology: Diagnosis and Management (A Colour Handbook). London, UK: Manson Publishing Ltd; 2011:48.

2. Kelly EB. Darier disease (DAR). In: Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2013:186-187.

3. Klausegger A, Laimer M, Bauer JW. Darier disease. [In German.] Hautarzt. 2013;64:22-25.

4. Ringpfeil F. Dermatologic disorders. In: NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:101.

5. Disorders of keratinization. In: Ostler HB, Maibach HI, Hoke AW, Schwab IR, eds. Diseases of the Eye and Skin: A Color Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:23-34.

6. Baran R, de Berker D, Holzberg M, Thomas L, eds. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and their Management. 4th ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:295-296.

7. Thiagarajan MK, Narasimhan M, Sankarasubramanian A. Darier disease with oral and esophageal involvement: a case report. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:843-846.

8. Medansky RS, Woloshin AA. Darier’s disease: an evaluation of its neuropsychiatric component. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:482-484.

9. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1631-1636.

10. Kamijo M, Nishiyama C, Takagi A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition restores ultraviolet B-induced downregulation of ATP2A2/SERCA2 in keratinocytes: possible therapeutic approach of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition for treatment of Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166: 1017-1022.

11. Brecher AR, Orlow SJ. Oral retinoid therapy for dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:171-182.

12. Beier C, Kaufmann R. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser ablation in Darier disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Arch Dermatol. 1999;35:423-427.