User login

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Overlap in a Pregnant Patient

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 5 weeks’ gestation was transferred to dermatology from an outside hospital with a full-body rash. Three days after noting a fever and generalized body aches, she developed a painful rash on the legs that had gradually spread to the arms, trunk, and face. Symptoms of eyelid pruritus and edema initially were improved with intravenous (IV) steroids at an emergency department visit, but they started to flare soon thereafter with worsening mucosal involvement and dysphagia. After a second visit to the emergency department and repeat treatment with IV steroids, she was transferred to our institution for a higher level of care.

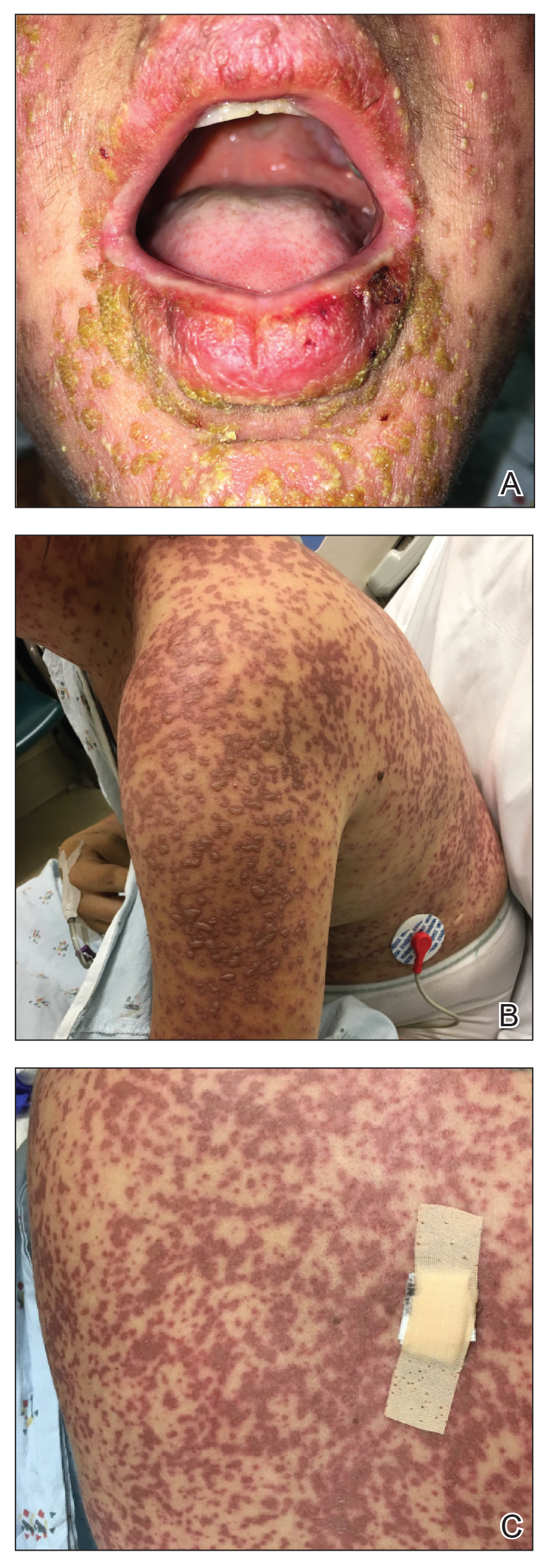

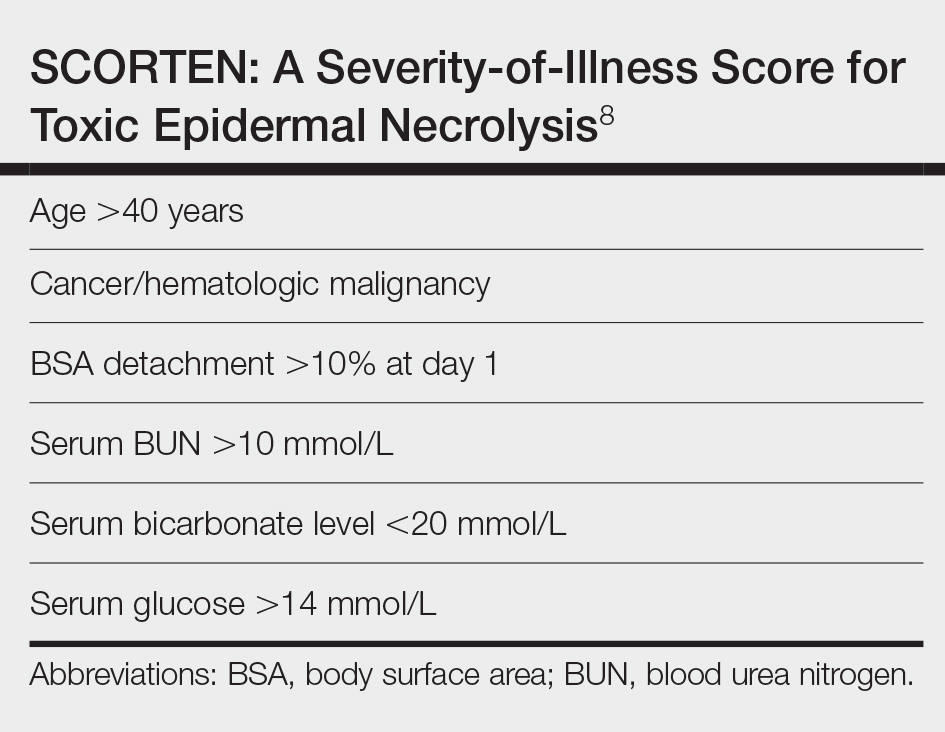

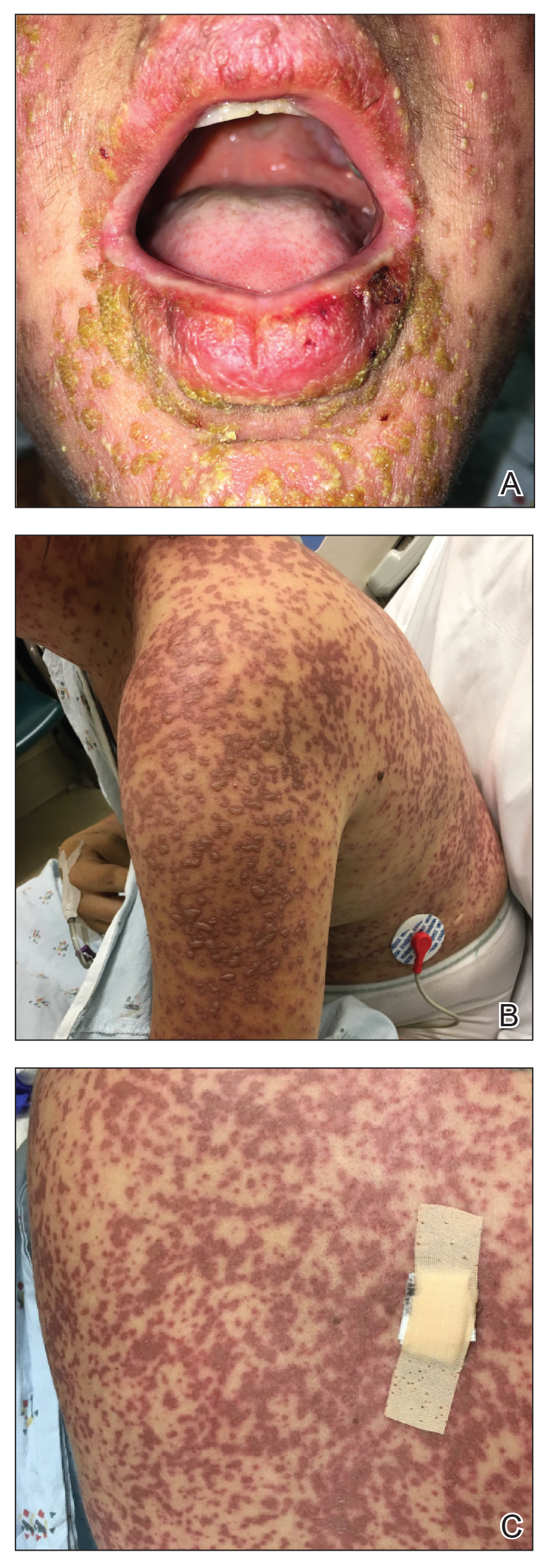

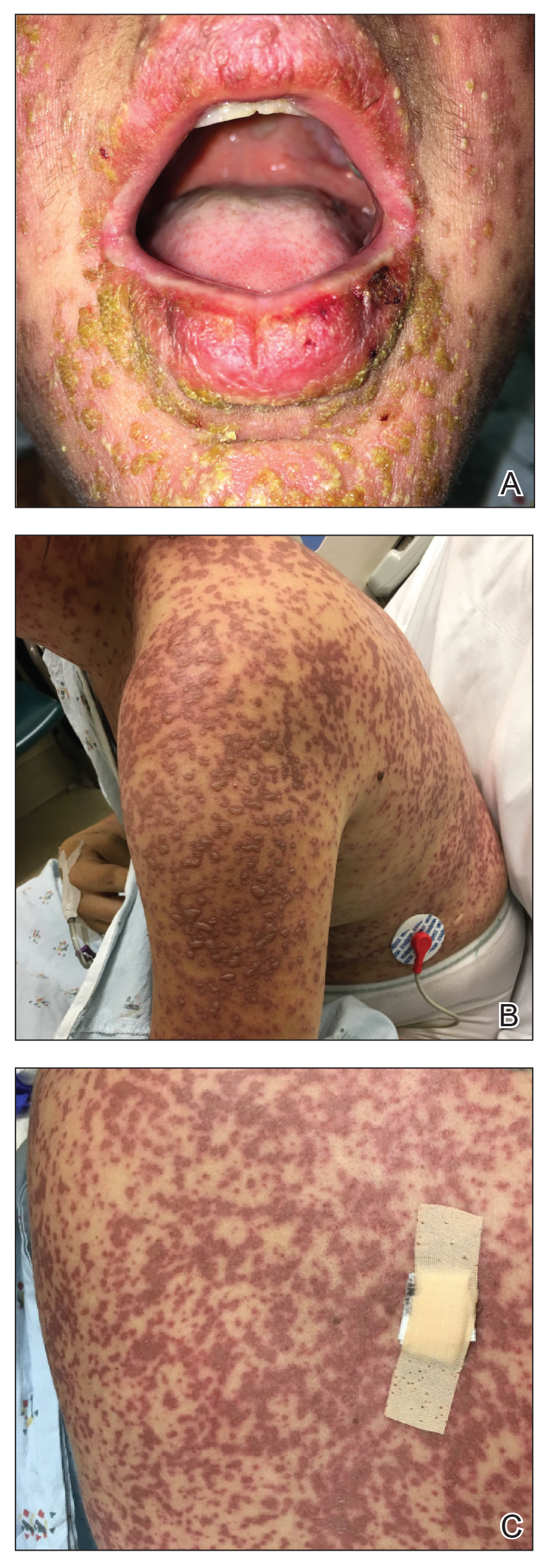

The patient denied taking any new medications in the 2 months prior to the onset of the rash. Her medication history only consisted of over-the-counter prenatal vitamins, a single use of over-the-counter migraine medication (containing acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine as active ingredients), and a possible use of ibuprofen or acetaminophen separately. She reported ocular discomfort and blurriness, dysphagia, dysuria, and vaginal discomfort. Physical examination revealed dusky red to violaceous macules and patches that involved approximately 65% of the body surface area (BSA), with bullae involving approximately 10% BSA. The face was diffusely red and edematous with crusted erosions and scattered bullae on the cheeks. Mucosal involvement was notable for injected conjunctivae and erosions present on the upper hard palate of the mouth and lips (Figure, A). Erythematous macules with dusky centers coalescing into patches with overlying vesicles and bullae were scattered on the arms (Figure, B), hands, trunk (Figure, C), and legs. The Nikolsky sign was positive. The vulva was swollen and covered with erythematous macules with dusky centers.

A biopsy from the upper back revealed a vacuolar interface with subepidermal bullae and confluent keratinocyte necrosis with many CD8+ cells and scattered granzyme B. Given these results in conjunction with the clinical findings, a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) overlap was made. In addition to providing supportive care, the patient was started on a 4-day course of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG)(3g/kg total) and prednisone 60 mg daily, tapered over several weeks with a good clinical response. At outpatient follow-up she was found to have postinflammatory hypopigmentation on the face, trunk, and extremities, as well as tear duct scarring, but she had no vulvovaginal scarring or stenosis. She was progressing well in her pregnancy with no serious complications for 4 months after admission, at which point she was lost to follow-up.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions with high morbidity and mortality. Medications are the leading trigger, followed by infection. The most common inciting medications include antibacterial sulfonamides, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nevirapine, and allopurinol. The onset of symptoms from 1 to 4 weeks combined with characteristic morphologic features helps distinguish SJS/TEN from other drug eruptions. The initial presentation classically consists of a flulike prodrome followed by mucocutaneous eruption. Skin lesions often present as a diffuse erythema or ill-defined, coalescing, erythematous macules with purpuric centers that may evolve into vesicles and bullae with sloughing of the skin. Histopathology reveals full-thickness epidermal necrosis with detachment.1

Erythema multiforme and Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) are high on the differential diagnosis. Distinguishing features of erythema multiforme include the morphology of targetoid lesions and a common distribution on the extremities, in addition to the limited bullae and epidermal detachment in comparison with SJS/TEN. In MIRM, mucositis often is more severe and extensive, with multiple mucosal surfaces affected. It typically has less cutaneous involvement than SJS/TEN, though clinical variants can include diffuse rash and affect fewer than 2 mucosal sites.2 Depending on the timing of rash onset, Mycoplasma IgM/IgG titers may be drawn to further support the diagnosis. A diagnosis of MIRM was not favored in our patient due to lack of respiratory symptoms, normal chest radiography, and negative Mycoplasma IgM and IgG titers.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap has been reported in pregnant patients, typically in association with HIV infection or new medication exposure.3 A combination of genetic susceptibility and an altered immune system during pregnancy may contribute to the pathogenesis, involving a cytotoxic T-cell mediated reaction with release of inflammatory cytokines.1 Interestingly, these factors that may predispose a patient to developing SJS/TEN may not pass on to the neonate, evidenced by a few cases that showed no reaction in the newborn when given the same offending drug.4

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis more frequently presents in the second or third trimester, with no increase in maternal mortality and an equally high survival rate of the fetus.1,5 Unique sequelae in pregnant patients may include vaginal stenosis, vulvar swelling, and postpartum sepsis. Fetal complications can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, and respiratory distress. The fetus rarely exhibits cutaneous manifestations of the disease.6

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN overlap in special patient populations such as pregnant women is vital. Supportive measures consisting of wound care, fluid and electrolyte management, infection monitoring, and nutritional support have sufficed in treating SJS/TEN in pregnant patients.3 Although adjunctive therapy with systemic corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors commonly are used in clinical practice, the safety of these treatments in pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN has not been established. However, use of these medications for other indications, primarily rheumatologic diseases, has been reported to be safe in the pregnant population.7 If necessary, glucocorticoids should be used in the lowest effective dose to avoid complications such as premature rupture of membranes; intrauterine growth restriction; and increased risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, osteoporosis, and infection. Little is known about IVIG use in pregnancy. While it has not been associated with increased risk of fetal malformations, it may cross the placenta in a notable amount when administered after 30 weeks’ gestation.7

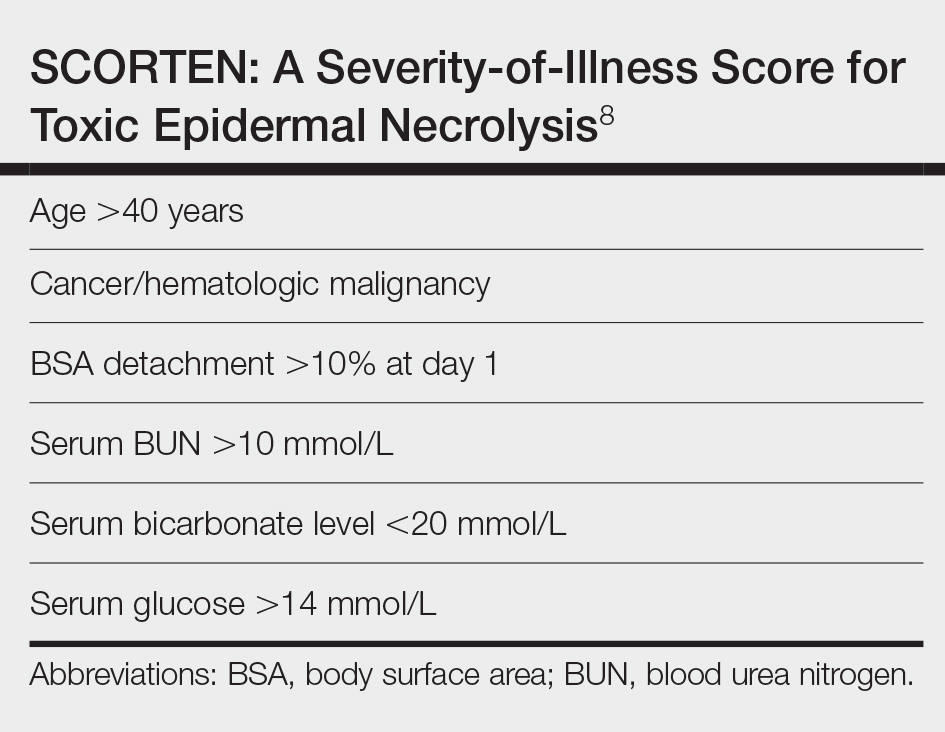

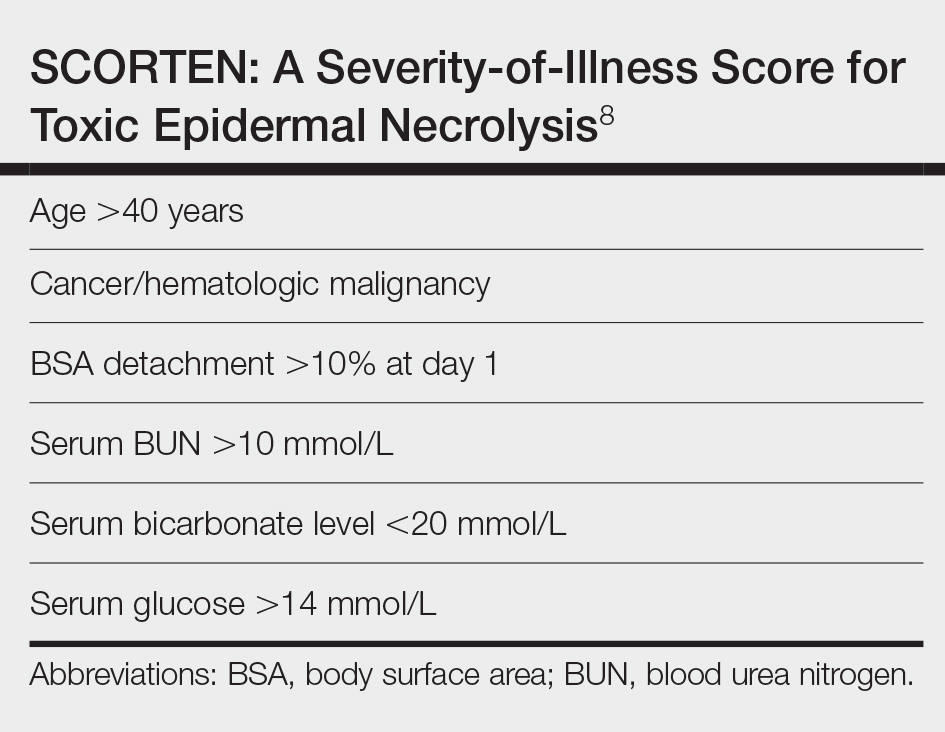

Unlike most cases of SJS/TEN in pregnancy that largely were associated with HIV infection or drug exposure, primarily antiretrovirals such as nevirapine or antiepileptics, our case is a rare incidence of SJS/TEN in a pregnant patient with no clear medication or infectious trigger. Although the causative drug was unclear, we suspected it was secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The patient had a SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) of 0, which portends a relatively good prognosis with an estimated mortality rate of approximately 3% (Table).8 However, the large BSA involvement of the morbilliform rash warranted aggressive management to prevent the involved skin from fully detaching.

1. Struck MF, Illert T, Liss Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:816-821. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181eed441

2. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

3. Knight L, Todd G, Muloiwa R, et al. Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: maternal and foetal outcomes in twenty-two consecutive pregnant HIV infected women. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135501

4. Velter C, Hotz C, Ingen-Housz-Oro S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during pregnancy: case report of a newborn treated with the culprit drug. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:224-225. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4607

5. El Daief SG, Das S, Ekekwe G, et al. A successful pregnancy outcome after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2014;34:445-446. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.914897

6. Rodriguez G, Trent JT, Mirzabeigi M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a mother and fetus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):96-98. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.023

7. Bermas BL. Safety of rheumatic disease medication use during pregnancy and lactation. UptoDate website. Updated March 24, 2021. Accessed December 16, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/safety-of-rheumatic-disease-medication-use-during-pregnancy-and-lactation#H11

8. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 5 weeks’ gestation was transferred to dermatology from an outside hospital with a full-body rash. Three days after noting a fever and generalized body aches, she developed a painful rash on the legs that had gradually spread to the arms, trunk, and face. Symptoms of eyelid pruritus and edema initially were improved with intravenous (IV) steroids at an emergency department visit, but they started to flare soon thereafter with worsening mucosal involvement and dysphagia. After a second visit to the emergency department and repeat treatment with IV steroids, she was transferred to our institution for a higher level of care.

The patient denied taking any new medications in the 2 months prior to the onset of the rash. Her medication history only consisted of over-the-counter prenatal vitamins, a single use of over-the-counter migraine medication (containing acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine as active ingredients), and a possible use of ibuprofen or acetaminophen separately. She reported ocular discomfort and blurriness, dysphagia, dysuria, and vaginal discomfort. Physical examination revealed dusky red to violaceous macules and patches that involved approximately 65% of the body surface area (BSA), with bullae involving approximately 10% BSA. The face was diffusely red and edematous with crusted erosions and scattered bullae on the cheeks. Mucosal involvement was notable for injected conjunctivae and erosions present on the upper hard palate of the mouth and lips (Figure, A). Erythematous macules with dusky centers coalescing into patches with overlying vesicles and bullae were scattered on the arms (Figure, B), hands, trunk (Figure, C), and legs. The Nikolsky sign was positive. The vulva was swollen and covered with erythematous macules with dusky centers.

A biopsy from the upper back revealed a vacuolar interface with subepidermal bullae and confluent keratinocyte necrosis with many CD8+ cells and scattered granzyme B. Given these results in conjunction with the clinical findings, a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) overlap was made. In addition to providing supportive care, the patient was started on a 4-day course of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG)(3g/kg total) and prednisone 60 mg daily, tapered over several weeks with a good clinical response. At outpatient follow-up she was found to have postinflammatory hypopigmentation on the face, trunk, and extremities, as well as tear duct scarring, but she had no vulvovaginal scarring or stenosis. She was progressing well in her pregnancy with no serious complications for 4 months after admission, at which point she was lost to follow-up.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions with high morbidity and mortality. Medications are the leading trigger, followed by infection. The most common inciting medications include antibacterial sulfonamides, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nevirapine, and allopurinol. The onset of symptoms from 1 to 4 weeks combined with characteristic morphologic features helps distinguish SJS/TEN from other drug eruptions. The initial presentation classically consists of a flulike prodrome followed by mucocutaneous eruption. Skin lesions often present as a diffuse erythema or ill-defined, coalescing, erythematous macules with purpuric centers that may evolve into vesicles and bullae with sloughing of the skin. Histopathology reveals full-thickness epidermal necrosis with detachment.1

Erythema multiforme and Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) are high on the differential diagnosis. Distinguishing features of erythema multiforme include the morphology of targetoid lesions and a common distribution on the extremities, in addition to the limited bullae and epidermal detachment in comparison with SJS/TEN. In MIRM, mucositis often is more severe and extensive, with multiple mucosal surfaces affected. It typically has less cutaneous involvement than SJS/TEN, though clinical variants can include diffuse rash and affect fewer than 2 mucosal sites.2 Depending on the timing of rash onset, Mycoplasma IgM/IgG titers may be drawn to further support the diagnosis. A diagnosis of MIRM was not favored in our patient due to lack of respiratory symptoms, normal chest radiography, and negative Mycoplasma IgM and IgG titers.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap has been reported in pregnant patients, typically in association with HIV infection or new medication exposure.3 A combination of genetic susceptibility and an altered immune system during pregnancy may contribute to the pathogenesis, involving a cytotoxic T-cell mediated reaction with release of inflammatory cytokines.1 Interestingly, these factors that may predispose a patient to developing SJS/TEN may not pass on to the neonate, evidenced by a few cases that showed no reaction in the newborn when given the same offending drug.4

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis more frequently presents in the second or third trimester, with no increase in maternal mortality and an equally high survival rate of the fetus.1,5 Unique sequelae in pregnant patients may include vaginal stenosis, vulvar swelling, and postpartum sepsis. Fetal complications can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, and respiratory distress. The fetus rarely exhibits cutaneous manifestations of the disease.6

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN overlap in special patient populations such as pregnant women is vital. Supportive measures consisting of wound care, fluid and electrolyte management, infection monitoring, and nutritional support have sufficed in treating SJS/TEN in pregnant patients.3 Although adjunctive therapy with systemic corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors commonly are used in clinical practice, the safety of these treatments in pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN has not been established. However, use of these medications for other indications, primarily rheumatologic diseases, has been reported to be safe in the pregnant population.7 If necessary, glucocorticoids should be used in the lowest effective dose to avoid complications such as premature rupture of membranes; intrauterine growth restriction; and increased risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, osteoporosis, and infection. Little is known about IVIG use in pregnancy. While it has not been associated with increased risk of fetal malformations, it may cross the placenta in a notable amount when administered after 30 weeks’ gestation.7

Unlike most cases of SJS/TEN in pregnancy that largely were associated with HIV infection or drug exposure, primarily antiretrovirals such as nevirapine or antiepileptics, our case is a rare incidence of SJS/TEN in a pregnant patient with no clear medication or infectious trigger. Although the causative drug was unclear, we suspected it was secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The patient had a SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) of 0, which portends a relatively good prognosis with an estimated mortality rate of approximately 3% (Table).8 However, the large BSA involvement of the morbilliform rash warranted aggressive management to prevent the involved skin from fully detaching.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 5 weeks’ gestation was transferred to dermatology from an outside hospital with a full-body rash. Three days after noting a fever and generalized body aches, she developed a painful rash on the legs that had gradually spread to the arms, trunk, and face. Symptoms of eyelid pruritus and edema initially were improved with intravenous (IV) steroids at an emergency department visit, but they started to flare soon thereafter with worsening mucosal involvement and dysphagia. After a second visit to the emergency department and repeat treatment with IV steroids, she was transferred to our institution for a higher level of care.

The patient denied taking any new medications in the 2 months prior to the onset of the rash. Her medication history only consisted of over-the-counter prenatal vitamins, a single use of over-the-counter migraine medication (containing acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine as active ingredients), and a possible use of ibuprofen or acetaminophen separately. She reported ocular discomfort and blurriness, dysphagia, dysuria, and vaginal discomfort. Physical examination revealed dusky red to violaceous macules and patches that involved approximately 65% of the body surface area (BSA), with bullae involving approximately 10% BSA. The face was diffusely red and edematous with crusted erosions and scattered bullae on the cheeks. Mucosal involvement was notable for injected conjunctivae and erosions present on the upper hard palate of the mouth and lips (Figure, A). Erythematous macules with dusky centers coalescing into patches with overlying vesicles and bullae were scattered on the arms (Figure, B), hands, trunk (Figure, C), and legs. The Nikolsky sign was positive. The vulva was swollen and covered with erythematous macules with dusky centers.

A biopsy from the upper back revealed a vacuolar interface with subepidermal bullae and confluent keratinocyte necrosis with many CD8+ cells and scattered granzyme B. Given these results in conjunction with the clinical findings, a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) overlap was made. In addition to providing supportive care, the patient was started on a 4-day course of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG)(3g/kg total) and prednisone 60 mg daily, tapered over several weeks with a good clinical response. At outpatient follow-up she was found to have postinflammatory hypopigmentation on the face, trunk, and extremities, as well as tear duct scarring, but she had no vulvovaginal scarring or stenosis. She was progressing well in her pregnancy with no serious complications for 4 months after admission, at which point she was lost to follow-up.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions with high morbidity and mortality. Medications are the leading trigger, followed by infection. The most common inciting medications include antibacterial sulfonamides, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nevirapine, and allopurinol. The onset of symptoms from 1 to 4 weeks combined with characteristic morphologic features helps distinguish SJS/TEN from other drug eruptions. The initial presentation classically consists of a flulike prodrome followed by mucocutaneous eruption. Skin lesions often present as a diffuse erythema or ill-defined, coalescing, erythematous macules with purpuric centers that may evolve into vesicles and bullae with sloughing of the skin. Histopathology reveals full-thickness epidermal necrosis with detachment.1

Erythema multiforme and Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) are high on the differential diagnosis. Distinguishing features of erythema multiforme include the morphology of targetoid lesions and a common distribution on the extremities, in addition to the limited bullae and epidermal detachment in comparison with SJS/TEN. In MIRM, mucositis often is more severe and extensive, with multiple mucosal surfaces affected. It typically has less cutaneous involvement than SJS/TEN, though clinical variants can include diffuse rash and affect fewer than 2 mucosal sites.2 Depending on the timing of rash onset, Mycoplasma IgM/IgG titers may be drawn to further support the diagnosis. A diagnosis of MIRM was not favored in our patient due to lack of respiratory symptoms, normal chest radiography, and negative Mycoplasma IgM and IgG titers.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap has been reported in pregnant patients, typically in association with HIV infection or new medication exposure.3 A combination of genetic susceptibility and an altered immune system during pregnancy may contribute to the pathogenesis, involving a cytotoxic T-cell mediated reaction with release of inflammatory cytokines.1 Interestingly, these factors that may predispose a patient to developing SJS/TEN may not pass on to the neonate, evidenced by a few cases that showed no reaction in the newborn when given the same offending drug.4

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis more frequently presents in the second or third trimester, with no increase in maternal mortality and an equally high survival rate of the fetus.1,5 Unique sequelae in pregnant patients may include vaginal stenosis, vulvar swelling, and postpartum sepsis. Fetal complications can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, and respiratory distress. The fetus rarely exhibits cutaneous manifestations of the disease.6

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN overlap in special patient populations such as pregnant women is vital. Supportive measures consisting of wound care, fluid and electrolyte management, infection monitoring, and nutritional support have sufficed in treating SJS/TEN in pregnant patients.3 Although adjunctive therapy with systemic corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors commonly are used in clinical practice, the safety of these treatments in pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN has not been established. However, use of these medications for other indications, primarily rheumatologic diseases, has been reported to be safe in the pregnant population.7 If necessary, glucocorticoids should be used in the lowest effective dose to avoid complications such as premature rupture of membranes; intrauterine growth restriction; and increased risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, osteoporosis, and infection. Little is known about IVIG use in pregnancy. While it has not been associated with increased risk of fetal malformations, it may cross the placenta in a notable amount when administered after 30 weeks’ gestation.7

Unlike most cases of SJS/TEN in pregnancy that largely were associated with HIV infection or drug exposure, primarily antiretrovirals such as nevirapine or antiepileptics, our case is a rare incidence of SJS/TEN in a pregnant patient with no clear medication or infectious trigger. Although the causative drug was unclear, we suspected it was secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The patient had a SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) of 0, which portends a relatively good prognosis with an estimated mortality rate of approximately 3% (Table).8 However, the large BSA involvement of the morbilliform rash warranted aggressive management to prevent the involved skin from fully detaching.

1. Struck MF, Illert T, Liss Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:816-821. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181eed441

2. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

3. Knight L, Todd G, Muloiwa R, et al. Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: maternal and foetal outcomes in twenty-two consecutive pregnant HIV infected women. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135501

4. Velter C, Hotz C, Ingen-Housz-Oro S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during pregnancy: case report of a newborn treated with the culprit drug. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:224-225. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4607

5. El Daief SG, Das S, Ekekwe G, et al. A successful pregnancy outcome after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2014;34:445-446. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.914897

6. Rodriguez G, Trent JT, Mirzabeigi M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a mother and fetus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):96-98. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.023

7. Bermas BL. Safety of rheumatic disease medication use during pregnancy and lactation. UptoDate website. Updated March 24, 2021. Accessed December 16, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/safety-of-rheumatic-disease-medication-use-during-pregnancy-and-lactation#H11

8. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

1. Struck MF, Illert T, Liss Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:816-821. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181eed441

2. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

3. Knight L, Todd G, Muloiwa R, et al. Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: maternal and foetal outcomes in twenty-two consecutive pregnant HIV infected women. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135501

4. Velter C, Hotz C, Ingen-Housz-Oro S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during pregnancy: case report of a newborn treated with the culprit drug. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:224-225. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4607

5. El Daief SG, Das S, Ekekwe G, et al. A successful pregnancy outcome after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2014;34:445-446. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.914897

6. Rodriguez G, Trent JT, Mirzabeigi M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a mother and fetus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):96-98. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.023

7. Bermas BL. Safety of rheumatic disease medication use during pregnancy and lactation. UptoDate website. Updated March 24, 2021. Accessed December 16, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/safety-of-rheumatic-disease-medication-use-during-pregnancy-and-lactation#H11

8. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

Practice Points

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions commonly presenting as drug eruptions.

- Pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN represent a special patient population that requires a multidisciplinary approach for management and treatment.

- The rates of adverse outcomes for pregnant patients with SJS/TEN are low with timely diagnosis, removal of the offending agent, and supportive care as mainstays of treatment.