User login

The woman who couldn’t stop eating

CASE Uncontrollable eating and weight gain

Ms. C, age 33, presents to an outpatient clinic with complaints of weight gain and “uncontrollable eating.” Ms. C says she’s gained >50 lb over the last year. She describes progressively frequent episodes of overeating during which she feels that she has no control over the amount of food she consumes. She reports eating as often as 10 times a day, and overeating to the point of physical discomfort during most meals. She gives an example of having recently consumed a large pizza, several portions of Chinese food, approximately 20 chicken wings, and half a chocolate cake for dinner. Ms. C admits that on several occasions she has vomited after meals due to feeling extremely full; however, she denies having done so intentionally. She also denies restricting her food intake, misusing laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

Ms. C expresses frustration and embarrassment with her eating and resulting weight gain. She says she has poor self-esteem, low energy and motivation, and poor concentration. She feels that her condition has significantly impacted her social life, romantic relationships, and family life. She admits she’s been avoiding dating and seeing friends due to her weight gain, and has been irritable with her teenage daughter.

During her initial evaluation, Ms. C is alert and oriented, with a linear and goal-directed thought process. She is somewhat irritable and guarded, wearing large sunglasses that cover most of her face, but is not overtly paranoid. Although she appears frustrated when discussing her condition, she denies feeling hopeless or helpless.

HISTORY Thyroid cancer and mood swings

Ms. C, who is single and unemployed, lives in an apartment with her teenage daughter, with whom she describes having a good relationship. She has been receiving disability benefits for the past 2 years after a motor vehicle accident resulted in multiple fractures of her arm and elbow, and subsequent chronic pain. Ms. C reports a distant history of “problems with alcohol,” but denies drinking any alcohol since being charged with driving under the influence several years ago. She has a 10 pack-year history of smoking and denies any history of illicit drug use.

Two years ago, Ms. C was diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma, and treated with surgical resection and a course of radiation. She has regular visits with her endocrinologist and has been prescribed oral levothyroxine, 150 mcg/d.

Ms. C reports a history of “mood swings” characterized by “snapping at people” and becoming irritable in response to stressful situations, but denies any past symptoms consistent with a manic or hypomanic episode. Ms. C has not been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, nor has she received any prior psychiatric treatment. She reluctantly discloses that approximately 3 years ago she had a less severe episode of uncontrollable eating and weight gain (20 to 30 lb). At that time, she was able to regain her desired physical appearance by going on the “Subway diet” and undergoing liposuction and plastic surgery.

At her current outpatient clinic visit, Ms. C expresses an interest in exploring bariatric surgery as a potential solution to her weight gain.

[polldaddy:10446186]

Continue to: EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

We refer Ms. C for a physical examination and routine blood analysis to rule out any medical contributors to her condition. Her physical examination is reported as normal, with no signs of skin changes, goiter, or exophthalmos. Ms. C is noted to be obese, with a body mass index of 37.2 kg/m2, and an abdominal circumference of 38.5 in.

A blood analysis shows that Ms. C has elevated triglyceride levels (202 mg/dL) and elevated cholesterol levels (210 mg/dL). Her thyroid function tests are within normal limits based on the dose of levothyroxine she’s been receiving. A pregnancy test is negative.

Ms. C gives the team at the clinic permission to contact her endocrinologist, who reports that he does not suspect that Ms. C’s drastic weight gain and abnormal eating patterns are attributable to her history of thyroid carcinoma because her thyroid function tests have been stable on her current regimen.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. C’s initial presentation, we strongly suspected a diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Several differential diagnoses were considered and carefully ruled out; Ms. C’s medical workup did not suggest that her weight gain was due to an active medical condition, and she did not meet DSM-5 criteria for a mood or psychotic disorder or anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

With an estimated lifetime prevalence in the United States of 2.6%, BED is the most prevalent eating disorder (compared with 0.6% for anorexia nervosa and 1% for bulimia nervosa).1 BED is more prevalent in women than in men, and the mean age of onset is mid-20s.

Continue to: BED may be difficult...

BED may be difficult to detect because patients may feel ashamed or guilty and are often hesitant to disclose and discuss their symptoms. Furthermore, they are frequently frustrated by the subjective loss of control over their behaviors. Patients with BED often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics.

Screening for eating disorders

Several screening instruments have been developed to help clinicians identify patients who may need further evaluation for possible diagnosis of an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED.2 The SCOFF questionnaire is composed of 5 brief clinician-administered questions to screen for eating disorders.2 The 7-item Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BED-7) is a screening instrument specific for BED that examines a patient’s eating patterns and behaviors during the past 3 months.3

In general, suspect BED in patients who have significant weight dissatisfaction, fluctuation in weight, and depressive symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria for binge eating disorder are shown in Table 14.

BED and comorbid psychiatric disorders

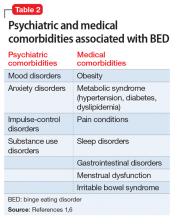

Patients with BED are more likely than the general population to have comorbid psychiatric disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Swanson et al5 found that 83.5% of adolescents who met criteria for BED also met criteria for at least 1 other psychiatric disorder, and 37% endorsed >3 concurrent psychiatric conditions. Once BED is confirmed, it is important to screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities that are often present in individuals with BED (Table 21,6).

The rates of diagnosis and treatment of BED remain low. This is likely due to patient factors such as shame and fear of stigma and clinician factors such as lack of awareness, ineffective communication, hesitation to discuss the sensitive topic, or insufficient knowledge about treatment options once BED is diagnosed.

[polldaddy:10446187]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

Ms. C is ambivalent about her BED diagnosis, and becomes angry about it when the proposed treatments do not involve bariatric surgery or cosmetic procedures. Ms. C is enrolled in weekly individual psychotherapy, where she receives a combination of CBT and psychodynamic therapy; however, her attendance is inconsistent. Ms. C is offered a trial of fluoxetine, but adamantly refuses, citing a relative who experienced adverse effects while receiving this type of antidepressant. Ms. C also refuses a trial of topiramate due to concerns of feeling sedated. Finally, she is offered a trial of lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, which was FDA-approved in 2015 to treat moderate to severe BED. We discuss the risks, benefits, and adverse effects of lisdexamfetamine with Ms. C; however, she is hesitant to start this medication and expresses increasing interest in obtaining a consultation for bariatric surgery. Ms. C is provided with extensive education about the risks and dangers of surgery before addressing her eating patterns, and the clinician provides validation, verbal support, and counseling. Ms. C eventually agrees to a trial of lisdexamfetamine, but her insurance denies coverage of this medication.

The authors’ observations

When developing an individualized treatment plan for a patient with BED, the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities should be considered. Treatment goals for patients with BED include:

- abstinence from binge eating

- sustainable weight loss and metabolic health

- reduction in symptoms associated with comorbid conditions

- improvement in self-esteem and overall quality of life.

A 2015 comparative effectiveness review of management and outcomes for patients with BED evaluated pharmacologic, psychologic, behavioral, and combined approaches for treating patients with BED.7 The results suggested that second-generation antidepressants, topiramate, and lisdexamfetamine were superior to placebo in reducing binge-eating episodes and achieving abstinence from binge-eating. Weight reduction was also achieved with topiramate and lisdexamfetamine, and antidepressants helped relieve symptoms of comorbid depression.

Various formats of CBT, including therapist-led and guided self-help, were also superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of binge-eating and promoting abstinence; however, they were generally not effective in treating depression or reducing patients’ weight.7

OUTCOME Fixated on surgery

We appeal the decision of Ms. C’s insurance company; however, during the appeals process, Ms. C becomes increasingly irritable and informs us that she has changed her mind and, with the reported support of her medical doctors, wishes to undergo bariatric surgery. Although we made multiple attempts to engage Ms. C in further treatment, she is lost to follow-up.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Diagnosing and managing patients with binge eating disorder (BED) can be challenging because patients may hesitate to seek help, and/or have psychiatric and medical comorbidities. They often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics. Once BED is confirmed, screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities. A combination of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions can benefit some patients with BED, but treatment should be individualized.

Related Resources

- National Eating Disorders Association. NEDA. www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/.

- Safer D, Telch C, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358.

2. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467-1468.

3. Herman BK, Deal LS, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Development of the 7-Item Binge-Eating Disorder screener (BEDS-7). Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(2):10.4088/PCC.15m01896. doi:10.4088/PCC.15m01896.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714.

6. Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, et al. Binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2017;40(2):255-266.

7. Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338312/. Published December 2015. Accessed July 29, 2019.

CASE Uncontrollable eating and weight gain

Ms. C, age 33, presents to an outpatient clinic with complaints of weight gain and “uncontrollable eating.” Ms. C says she’s gained >50 lb over the last year. She describes progressively frequent episodes of overeating during which she feels that she has no control over the amount of food she consumes. She reports eating as often as 10 times a day, and overeating to the point of physical discomfort during most meals. She gives an example of having recently consumed a large pizza, several portions of Chinese food, approximately 20 chicken wings, and half a chocolate cake for dinner. Ms. C admits that on several occasions she has vomited after meals due to feeling extremely full; however, she denies having done so intentionally. She also denies restricting her food intake, misusing laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

Ms. C expresses frustration and embarrassment with her eating and resulting weight gain. She says she has poor self-esteem, low energy and motivation, and poor concentration. She feels that her condition has significantly impacted her social life, romantic relationships, and family life. She admits she’s been avoiding dating and seeing friends due to her weight gain, and has been irritable with her teenage daughter.

During her initial evaluation, Ms. C is alert and oriented, with a linear and goal-directed thought process. She is somewhat irritable and guarded, wearing large sunglasses that cover most of her face, but is not overtly paranoid. Although she appears frustrated when discussing her condition, she denies feeling hopeless or helpless.

HISTORY Thyroid cancer and mood swings

Ms. C, who is single and unemployed, lives in an apartment with her teenage daughter, with whom she describes having a good relationship. She has been receiving disability benefits for the past 2 years after a motor vehicle accident resulted in multiple fractures of her arm and elbow, and subsequent chronic pain. Ms. C reports a distant history of “problems with alcohol,” but denies drinking any alcohol since being charged with driving under the influence several years ago. She has a 10 pack-year history of smoking and denies any history of illicit drug use.

Two years ago, Ms. C was diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma, and treated with surgical resection and a course of radiation. She has regular visits with her endocrinologist and has been prescribed oral levothyroxine, 150 mcg/d.

Ms. C reports a history of “mood swings” characterized by “snapping at people” and becoming irritable in response to stressful situations, but denies any past symptoms consistent with a manic or hypomanic episode. Ms. C has not been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, nor has she received any prior psychiatric treatment. She reluctantly discloses that approximately 3 years ago she had a less severe episode of uncontrollable eating and weight gain (20 to 30 lb). At that time, she was able to regain her desired physical appearance by going on the “Subway diet” and undergoing liposuction and plastic surgery.

At her current outpatient clinic visit, Ms. C expresses an interest in exploring bariatric surgery as a potential solution to her weight gain.

[polldaddy:10446186]

Continue to: EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

We refer Ms. C for a physical examination and routine blood analysis to rule out any medical contributors to her condition. Her physical examination is reported as normal, with no signs of skin changes, goiter, or exophthalmos. Ms. C is noted to be obese, with a body mass index of 37.2 kg/m2, and an abdominal circumference of 38.5 in.

A blood analysis shows that Ms. C has elevated triglyceride levels (202 mg/dL) and elevated cholesterol levels (210 mg/dL). Her thyroid function tests are within normal limits based on the dose of levothyroxine she’s been receiving. A pregnancy test is negative.

Ms. C gives the team at the clinic permission to contact her endocrinologist, who reports that he does not suspect that Ms. C’s drastic weight gain and abnormal eating patterns are attributable to her history of thyroid carcinoma because her thyroid function tests have been stable on her current regimen.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. C’s initial presentation, we strongly suspected a diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Several differential diagnoses were considered and carefully ruled out; Ms. C’s medical workup did not suggest that her weight gain was due to an active medical condition, and she did not meet DSM-5 criteria for a mood or psychotic disorder or anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

With an estimated lifetime prevalence in the United States of 2.6%, BED is the most prevalent eating disorder (compared with 0.6% for anorexia nervosa and 1% for bulimia nervosa).1 BED is more prevalent in women than in men, and the mean age of onset is mid-20s.

Continue to: BED may be difficult...

BED may be difficult to detect because patients may feel ashamed or guilty and are often hesitant to disclose and discuss their symptoms. Furthermore, they are frequently frustrated by the subjective loss of control over their behaviors. Patients with BED often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics.

Screening for eating disorders

Several screening instruments have been developed to help clinicians identify patients who may need further evaluation for possible diagnosis of an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED.2 The SCOFF questionnaire is composed of 5 brief clinician-administered questions to screen for eating disorders.2 The 7-item Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BED-7) is a screening instrument specific for BED that examines a patient’s eating patterns and behaviors during the past 3 months.3

In general, suspect BED in patients who have significant weight dissatisfaction, fluctuation in weight, and depressive symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria for binge eating disorder are shown in Table 14.

BED and comorbid psychiatric disorders

Patients with BED are more likely than the general population to have comorbid psychiatric disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Swanson et al5 found that 83.5% of adolescents who met criteria for BED also met criteria for at least 1 other psychiatric disorder, and 37% endorsed >3 concurrent psychiatric conditions. Once BED is confirmed, it is important to screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities that are often present in individuals with BED (Table 21,6).

The rates of diagnosis and treatment of BED remain low. This is likely due to patient factors such as shame and fear of stigma and clinician factors such as lack of awareness, ineffective communication, hesitation to discuss the sensitive topic, or insufficient knowledge about treatment options once BED is diagnosed.

[polldaddy:10446187]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

Ms. C is ambivalent about her BED diagnosis, and becomes angry about it when the proposed treatments do not involve bariatric surgery or cosmetic procedures. Ms. C is enrolled in weekly individual psychotherapy, where she receives a combination of CBT and psychodynamic therapy; however, her attendance is inconsistent. Ms. C is offered a trial of fluoxetine, but adamantly refuses, citing a relative who experienced adverse effects while receiving this type of antidepressant. Ms. C also refuses a trial of topiramate due to concerns of feeling sedated. Finally, she is offered a trial of lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, which was FDA-approved in 2015 to treat moderate to severe BED. We discuss the risks, benefits, and adverse effects of lisdexamfetamine with Ms. C; however, she is hesitant to start this medication and expresses increasing interest in obtaining a consultation for bariatric surgery. Ms. C is provided with extensive education about the risks and dangers of surgery before addressing her eating patterns, and the clinician provides validation, verbal support, and counseling. Ms. C eventually agrees to a trial of lisdexamfetamine, but her insurance denies coverage of this medication.

The authors’ observations

When developing an individualized treatment plan for a patient with BED, the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities should be considered. Treatment goals for patients with BED include:

- abstinence from binge eating

- sustainable weight loss and metabolic health

- reduction in symptoms associated with comorbid conditions

- improvement in self-esteem and overall quality of life.

A 2015 comparative effectiveness review of management and outcomes for patients with BED evaluated pharmacologic, psychologic, behavioral, and combined approaches for treating patients with BED.7 The results suggested that second-generation antidepressants, topiramate, and lisdexamfetamine were superior to placebo in reducing binge-eating episodes and achieving abstinence from binge-eating. Weight reduction was also achieved with topiramate and lisdexamfetamine, and antidepressants helped relieve symptoms of comorbid depression.

Various formats of CBT, including therapist-led and guided self-help, were also superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of binge-eating and promoting abstinence; however, they were generally not effective in treating depression or reducing patients’ weight.7

OUTCOME Fixated on surgery

We appeal the decision of Ms. C’s insurance company; however, during the appeals process, Ms. C becomes increasingly irritable and informs us that she has changed her mind and, with the reported support of her medical doctors, wishes to undergo bariatric surgery. Although we made multiple attempts to engage Ms. C in further treatment, she is lost to follow-up.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Diagnosing and managing patients with binge eating disorder (BED) can be challenging because patients may hesitate to seek help, and/or have psychiatric and medical comorbidities. They often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics. Once BED is confirmed, screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities. A combination of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions can benefit some patients with BED, but treatment should be individualized.

Related Resources

- National Eating Disorders Association. NEDA. www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/.

- Safer D, Telch C, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Topiramate • Topamax

CASE Uncontrollable eating and weight gain

Ms. C, age 33, presents to an outpatient clinic with complaints of weight gain and “uncontrollable eating.” Ms. C says she’s gained >50 lb over the last year. She describes progressively frequent episodes of overeating during which she feels that she has no control over the amount of food she consumes. She reports eating as often as 10 times a day, and overeating to the point of physical discomfort during most meals. She gives an example of having recently consumed a large pizza, several portions of Chinese food, approximately 20 chicken wings, and half a chocolate cake for dinner. Ms. C admits that on several occasions she has vomited after meals due to feeling extremely full; however, she denies having done so intentionally. She also denies restricting her food intake, misusing laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

Ms. C expresses frustration and embarrassment with her eating and resulting weight gain. She says she has poor self-esteem, low energy and motivation, and poor concentration. She feels that her condition has significantly impacted her social life, romantic relationships, and family life. She admits she’s been avoiding dating and seeing friends due to her weight gain, and has been irritable with her teenage daughter.

During her initial evaluation, Ms. C is alert and oriented, with a linear and goal-directed thought process. She is somewhat irritable and guarded, wearing large sunglasses that cover most of her face, but is not overtly paranoid. Although she appears frustrated when discussing her condition, she denies feeling hopeless or helpless.

HISTORY Thyroid cancer and mood swings

Ms. C, who is single and unemployed, lives in an apartment with her teenage daughter, with whom she describes having a good relationship. She has been receiving disability benefits for the past 2 years after a motor vehicle accident resulted in multiple fractures of her arm and elbow, and subsequent chronic pain. Ms. C reports a distant history of “problems with alcohol,” but denies drinking any alcohol since being charged with driving under the influence several years ago. She has a 10 pack-year history of smoking and denies any history of illicit drug use.

Two years ago, Ms. C was diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma, and treated with surgical resection and a course of radiation. She has regular visits with her endocrinologist and has been prescribed oral levothyroxine, 150 mcg/d.

Ms. C reports a history of “mood swings” characterized by “snapping at people” and becoming irritable in response to stressful situations, but denies any past symptoms consistent with a manic or hypomanic episode. Ms. C has not been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, nor has she received any prior psychiatric treatment. She reluctantly discloses that approximately 3 years ago she had a less severe episode of uncontrollable eating and weight gain (20 to 30 lb). At that time, she was able to regain her desired physical appearance by going on the “Subway diet” and undergoing liposuction and plastic surgery.

At her current outpatient clinic visit, Ms. C expresses an interest in exploring bariatric surgery as a potential solution to her weight gain.

[polldaddy:10446186]

Continue to: EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

We refer Ms. C for a physical examination and routine blood analysis to rule out any medical contributors to her condition. Her physical examination is reported as normal, with no signs of skin changes, goiter, or exophthalmos. Ms. C is noted to be obese, with a body mass index of 37.2 kg/m2, and an abdominal circumference of 38.5 in.

A blood analysis shows that Ms. C has elevated triglyceride levels (202 mg/dL) and elevated cholesterol levels (210 mg/dL). Her thyroid function tests are within normal limits based on the dose of levothyroxine she’s been receiving. A pregnancy test is negative.

Ms. C gives the team at the clinic permission to contact her endocrinologist, who reports that he does not suspect that Ms. C’s drastic weight gain and abnormal eating patterns are attributable to her history of thyroid carcinoma because her thyroid function tests have been stable on her current regimen.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. C’s initial presentation, we strongly suspected a diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Several differential diagnoses were considered and carefully ruled out; Ms. C’s medical workup did not suggest that her weight gain was due to an active medical condition, and she did not meet DSM-5 criteria for a mood or psychotic disorder or anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

With an estimated lifetime prevalence in the United States of 2.6%, BED is the most prevalent eating disorder (compared with 0.6% for anorexia nervosa and 1% for bulimia nervosa).1 BED is more prevalent in women than in men, and the mean age of onset is mid-20s.

Continue to: BED may be difficult...

BED may be difficult to detect because patients may feel ashamed or guilty and are often hesitant to disclose and discuss their symptoms. Furthermore, they are frequently frustrated by the subjective loss of control over their behaviors. Patients with BED often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics.

Screening for eating disorders

Several screening instruments have been developed to help clinicians identify patients who may need further evaluation for possible diagnosis of an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED.2 The SCOFF questionnaire is composed of 5 brief clinician-administered questions to screen for eating disorders.2 The 7-item Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BED-7) is a screening instrument specific for BED that examines a patient’s eating patterns and behaviors during the past 3 months.3

In general, suspect BED in patients who have significant weight dissatisfaction, fluctuation in weight, and depressive symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria for binge eating disorder are shown in Table 14.

BED and comorbid psychiatric disorders

Patients with BED are more likely than the general population to have comorbid psychiatric disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Swanson et al5 found that 83.5% of adolescents who met criteria for BED also met criteria for at least 1 other psychiatric disorder, and 37% endorsed >3 concurrent psychiatric conditions. Once BED is confirmed, it is important to screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities that are often present in individuals with BED (Table 21,6).

The rates of diagnosis and treatment of BED remain low. This is likely due to patient factors such as shame and fear of stigma and clinician factors such as lack of awareness, ineffective communication, hesitation to discuss the sensitive topic, or insufficient knowledge about treatment options once BED is diagnosed.

[polldaddy:10446187]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

Ms. C is ambivalent about her BED diagnosis, and becomes angry about it when the proposed treatments do not involve bariatric surgery or cosmetic procedures. Ms. C is enrolled in weekly individual psychotherapy, where she receives a combination of CBT and psychodynamic therapy; however, her attendance is inconsistent. Ms. C is offered a trial of fluoxetine, but adamantly refuses, citing a relative who experienced adverse effects while receiving this type of antidepressant. Ms. C also refuses a trial of topiramate due to concerns of feeling sedated. Finally, she is offered a trial of lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, which was FDA-approved in 2015 to treat moderate to severe BED. We discuss the risks, benefits, and adverse effects of lisdexamfetamine with Ms. C; however, she is hesitant to start this medication and expresses increasing interest in obtaining a consultation for bariatric surgery. Ms. C is provided with extensive education about the risks and dangers of surgery before addressing her eating patterns, and the clinician provides validation, verbal support, and counseling. Ms. C eventually agrees to a trial of lisdexamfetamine, but her insurance denies coverage of this medication.

The authors’ observations

When developing an individualized treatment plan for a patient with BED, the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities should be considered. Treatment goals for patients with BED include:

- abstinence from binge eating

- sustainable weight loss and metabolic health

- reduction in symptoms associated with comorbid conditions

- improvement in self-esteem and overall quality of life.

A 2015 comparative effectiveness review of management and outcomes for patients with BED evaluated pharmacologic, psychologic, behavioral, and combined approaches for treating patients with BED.7 The results suggested that second-generation antidepressants, topiramate, and lisdexamfetamine were superior to placebo in reducing binge-eating episodes and achieving abstinence from binge-eating. Weight reduction was also achieved with topiramate and lisdexamfetamine, and antidepressants helped relieve symptoms of comorbid depression.

Various formats of CBT, including therapist-led and guided self-help, were also superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of binge-eating and promoting abstinence; however, they were generally not effective in treating depression or reducing patients’ weight.7

OUTCOME Fixated on surgery

We appeal the decision of Ms. C’s insurance company; however, during the appeals process, Ms. C becomes increasingly irritable and informs us that she has changed her mind and, with the reported support of her medical doctors, wishes to undergo bariatric surgery. Although we made multiple attempts to engage Ms. C in further treatment, she is lost to follow-up.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Diagnosing and managing patients with binge eating disorder (BED) can be challenging because patients may hesitate to seek help, and/or have psychiatric and medical comorbidities. They often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics. Once BED is confirmed, screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities. A combination of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions can benefit some patients with BED, but treatment should be individualized.

Related Resources

- National Eating Disorders Association. NEDA. www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/.

- Safer D, Telch C, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358.

2. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467-1468.

3. Herman BK, Deal LS, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Development of the 7-Item Binge-Eating Disorder screener (BEDS-7). Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(2):10.4088/PCC.15m01896. doi:10.4088/PCC.15m01896.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714.

6. Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, et al. Binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2017;40(2):255-266.

7. Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338312/. Published December 2015. Accessed July 29, 2019.

1. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358.

2. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467-1468.

3. Herman BK, Deal LS, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Development of the 7-Item Binge-Eating Disorder screener (BEDS-7). Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(2):10.4088/PCC.15m01896. doi:10.4088/PCC.15m01896.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714.

6. Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, et al. Binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2017;40(2):255-266.

7. Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338312/. Published December 2015. Accessed July 29, 2019.