User login

Oral Verrucous Plaques in a Patient With Urothelial Cancer

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Acanthosis Nigricans

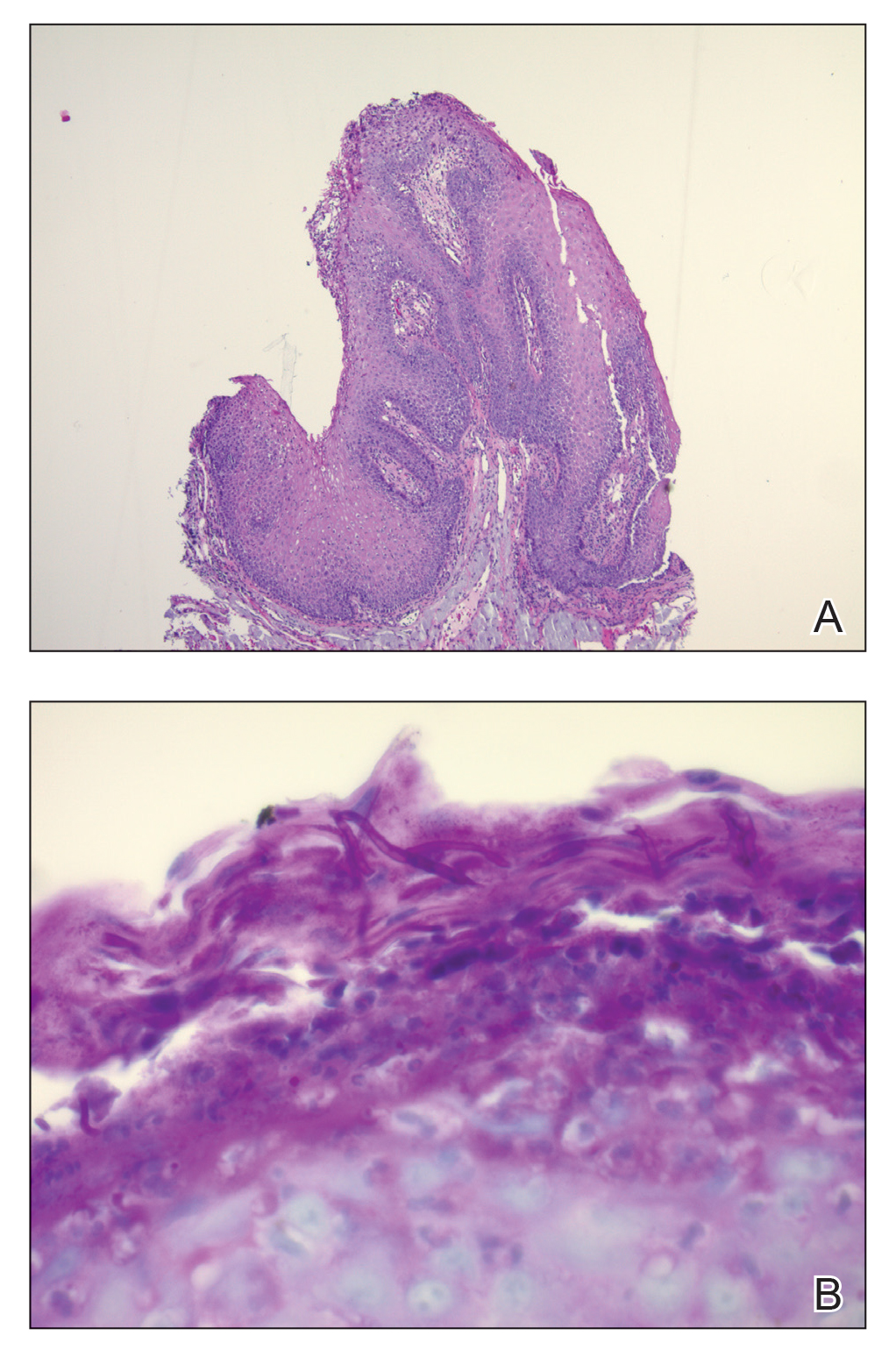

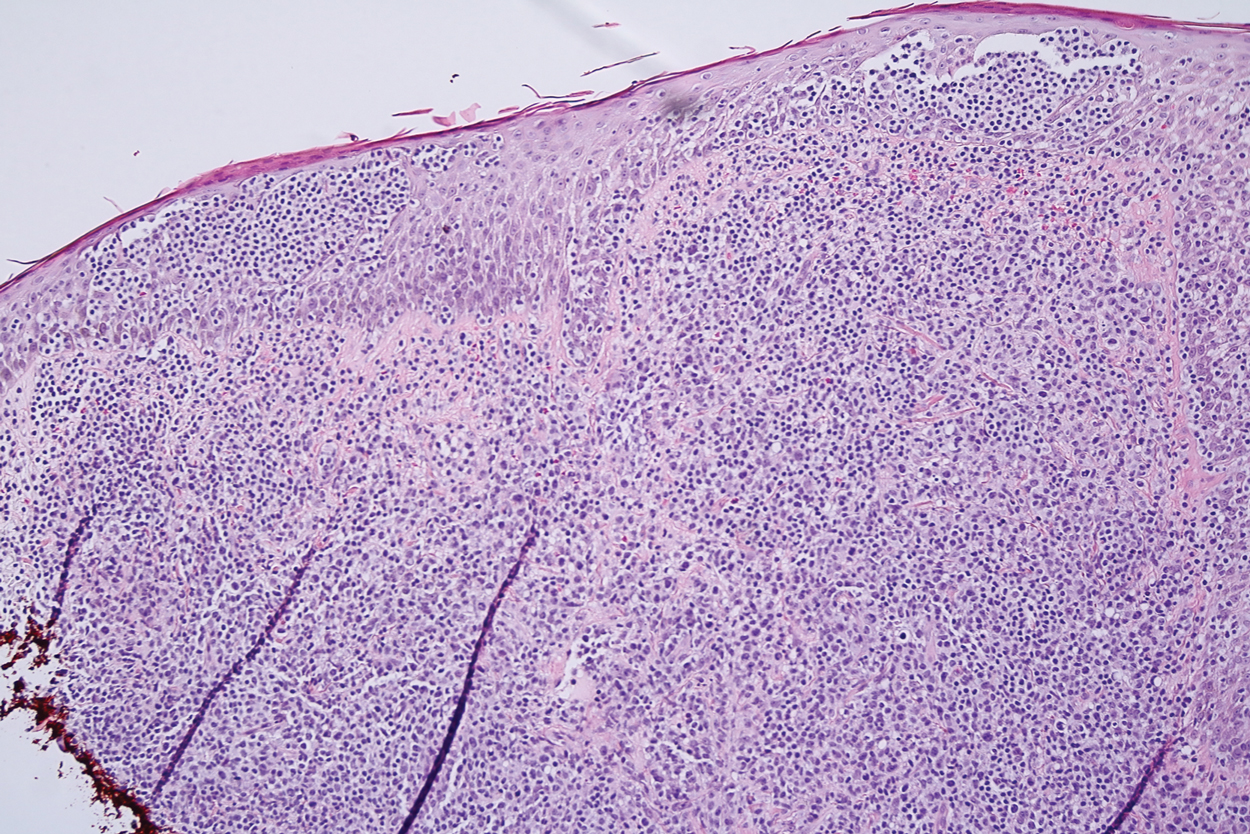

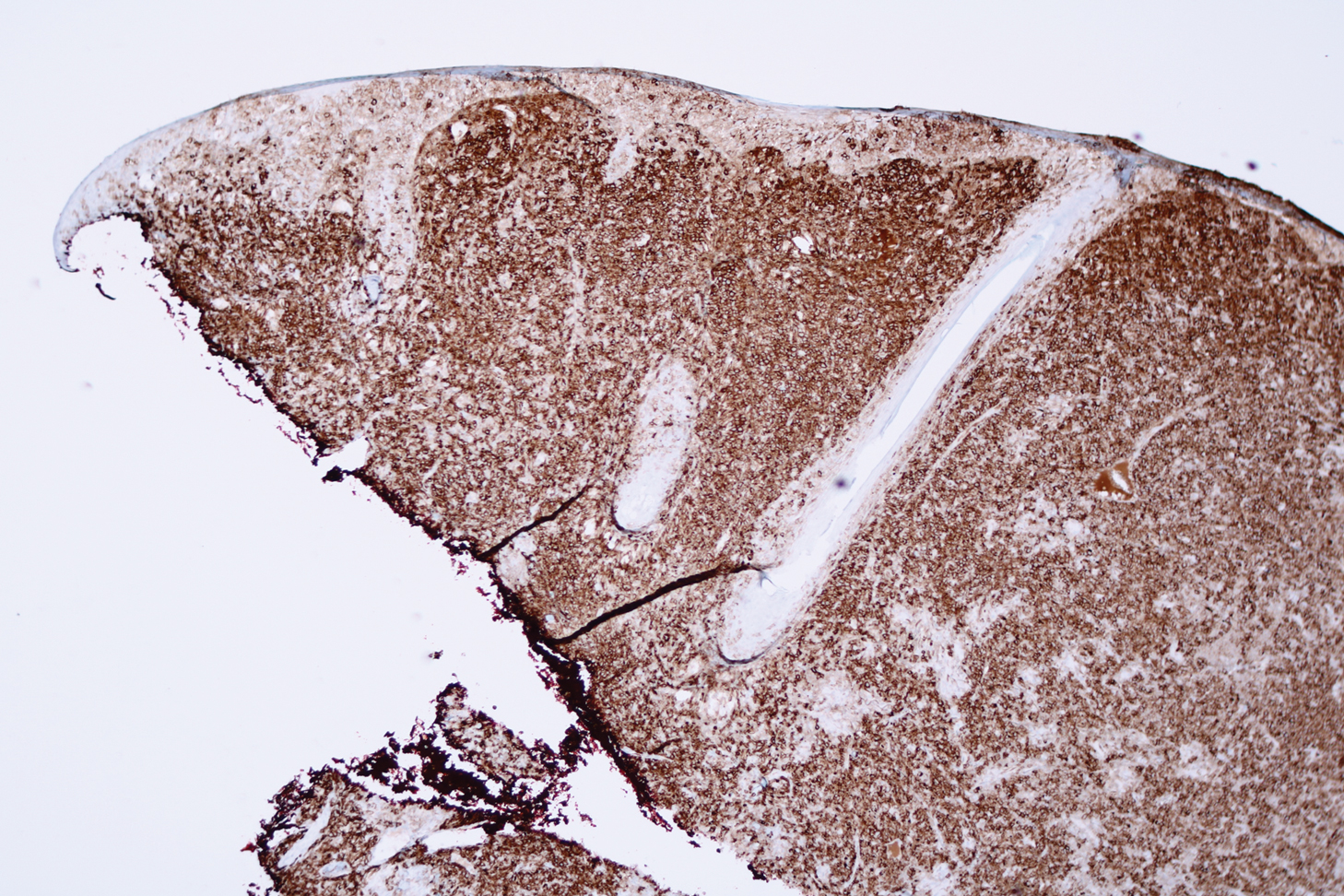

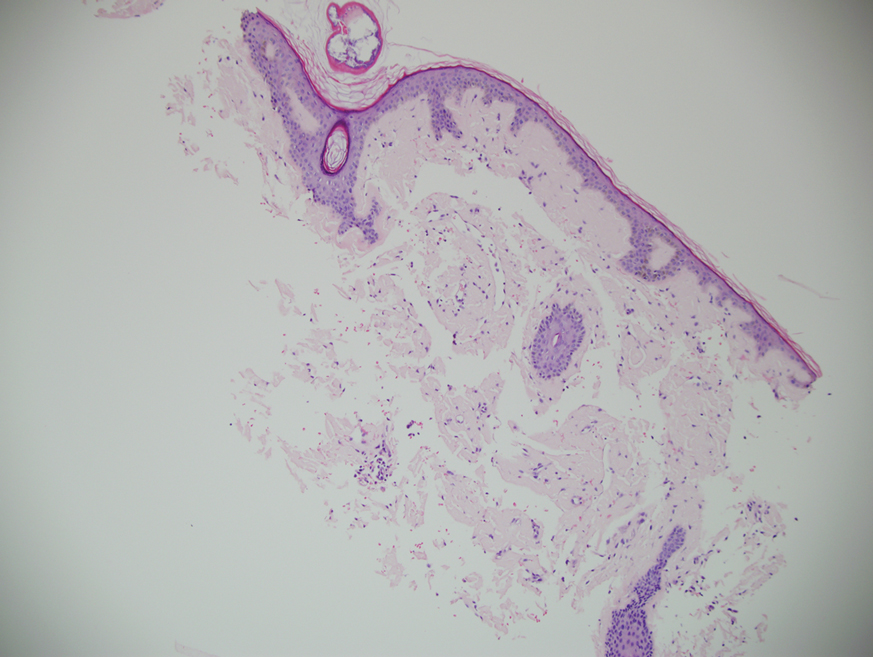

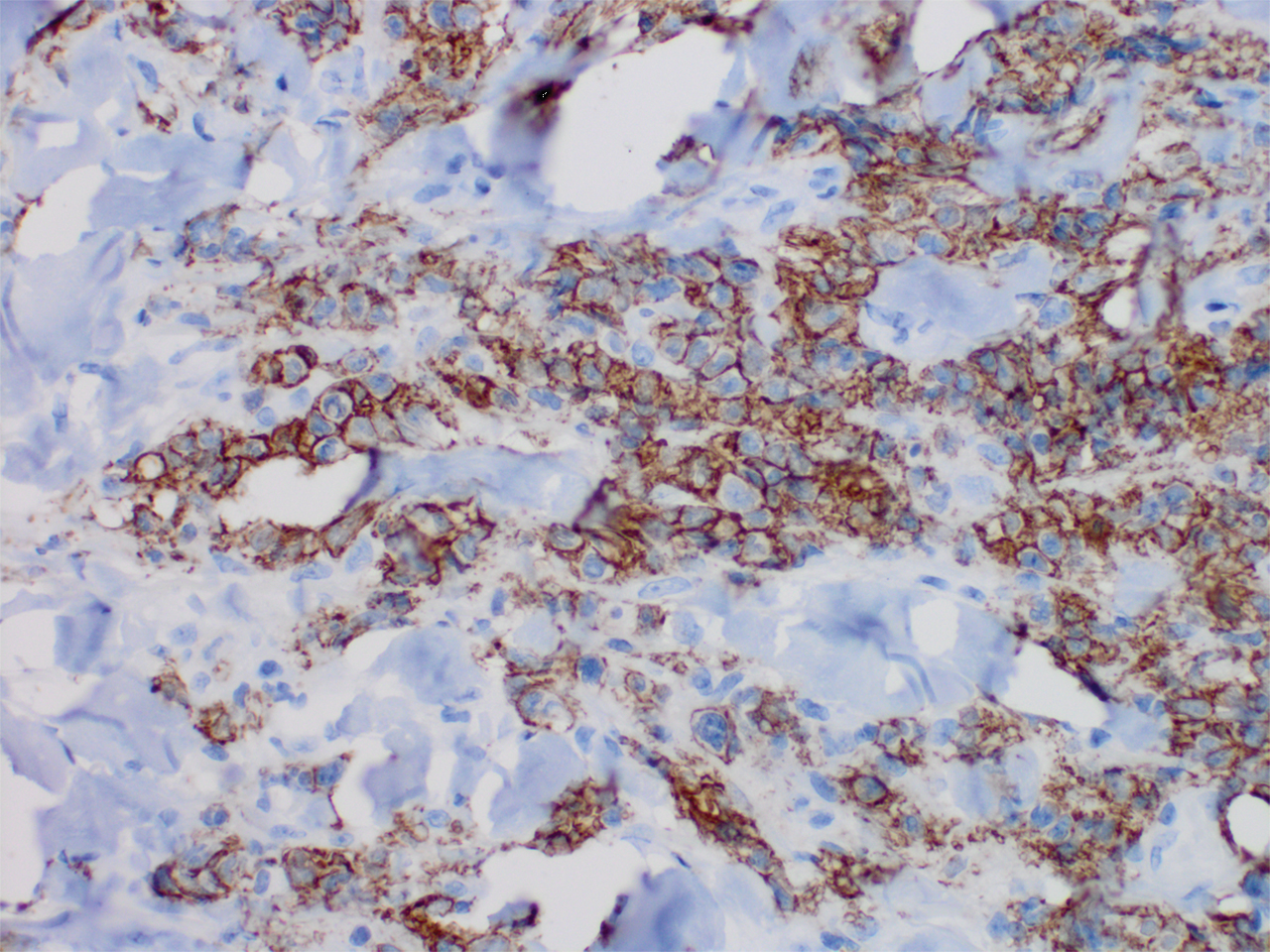

Histopathologic examination demonstrated verrucous epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). Fungal organisms were identified with an Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure, B). The organisms demonstrated a vertical orientation in relation to the mucosal surface, which was consistent with candidal organisms.

Given the rapid eruption of these plaques, the distribution on the oral and palmar surfaces (tripe palms), and the minimal improvement with both systemic steroids and antifungal treatment, a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans with secondary candidal infection was made. Drug-induced cheilitis was considered; however, improvement with discontinuation of the suspected offending drug would have been expected. Although chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis was possible, more prompt improvement upon initiation of systemic antifungal therapy would have been observed. Oral Crohn disease should be included in the differential, but it was unlikely given the lack of granulomas on pathology and absence of history of gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome also was unlikely given the lack of facial nerve palsy as well as the lack of granulomas on pathology. Furthermore, none of these options would be associated with tripe palms, as seen in our patient.

Acanthosis nigricans is a localized skin disorder characterized by hyperpigmented velvety plaques arising in flexural and intertriginous regions. Although most cases (80%) are associated with idiopathic or benign conditions, the link between acanthosis nigricans and an underlying malignancy has been well documented.1-3 Most commonly associated with an underlying intra-abdominal malignancy (often gastric carcinoma), the lesions of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans are indistinguishable from their benign counterparts.1,4 When the condition presents abruptly and extensively in a nonobese patient, prompt workup for malignancy should be initiated. Rapid onset and atypical distribution (ie, palmar, perioral, or mucosal) more commonly is associated with a paraneoplastic etiology.5,6

Histopathology for acanthosis nigricans shows hyperkeratosis and epidermal papillomatosis. Horn pseudocyst formation is possible, but usually no hyperpigmentation is observed. The findings typically are indistinguishable from seborrheic keratoses, epidermal nevi, or lesions of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud.2

The underlying pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans is poorly understood. In the benign subtype, insulin resistance commonly has been described. In the paraneoplastic subtype, it is proposed that the tumor produces a transforming growth factor that mimics epidermal growth factor and leads to keratinocyte proliferation.7,8 Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans has the potential to arise at any point of tumor development, further contributing to the diagnostic challenge. Treatment of the skin lesions involves management of the underlying malignancy. Unfortunately, many such malignancies often are at an advanced stage, and subsequent prognosis is poor.2

- Shah A, Jack A, Liu H, et al. Neoplastic/paraneoplastic dermatitis, fasciitis, and panniculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:573-592.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kim EJ. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019:2441-2464.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong WS. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Yu Q, Li XL, Ji G, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue for gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:208.

- Mohrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. Tripe palms and malignant acanthosis nigricans: cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2.

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Acanthosis Nigricans

Histopathologic examination demonstrated verrucous epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). Fungal organisms were identified with an Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure, B). The organisms demonstrated a vertical orientation in relation to the mucosal surface, which was consistent with candidal organisms.

Given the rapid eruption of these plaques, the distribution on the oral and palmar surfaces (tripe palms), and the minimal improvement with both systemic steroids and antifungal treatment, a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans with secondary candidal infection was made. Drug-induced cheilitis was considered; however, improvement with discontinuation of the suspected offending drug would have been expected. Although chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis was possible, more prompt improvement upon initiation of systemic antifungal therapy would have been observed. Oral Crohn disease should be included in the differential, but it was unlikely given the lack of granulomas on pathology and absence of history of gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome also was unlikely given the lack of facial nerve palsy as well as the lack of granulomas on pathology. Furthermore, none of these options would be associated with tripe palms, as seen in our patient.

Acanthosis nigricans is a localized skin disorder characterized by hyperpigmented velvety plaques arising in flexural and intertriginous regions. Although most cases (80%) are associated with idiopathic or benign conditions, the link between acanthosis nigricans and an underlying malignancy has been well documented.1-3 Most commonly associated with an underlying intra-abdominal malignancy (often gastric carcinoma), the lesions of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans are indistinguishable from their benign counterparts.1,4 When the condition presents abruptly and extensively in a nonobese patient, prompt workup for malignancy should be initiated. Rapid onset and atypical distribution (ie, palmar, perioral, or mucosal) more commonly is associated with a paraneoplastic etiology.5,6

Histopathology for acanthosis nigricans shows hyperkeratosis and epidermal papillomatosis. Horn pseudocyst formation is possible, but usually no hyperpigmentation is observed. The findings typically are indistinguishable from seborrheic keratoses, epidermal nevi, or lesions of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud.2

The underlying pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans is poorly understood. In the benign subtype, insulin resistance commonly has been described. In the paraneoplastic subtype, it is proposed that the tumor produces a transforming growth factor that mimics epidermal growth factor and leads to keratinocyte proliferation.7,8 Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans has the potential to arise at any point of tumor development, further contributing to the diagnostic challenge. Treatment of the skin lesions involves management of the underlying malignancy. Unfortunately, many such malignancies often are at an advanced stage, and subsequent prognosis is poor.2

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Acanthosis Nigricans

Histopathologic examination demonstrated verrucous epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). Fungal organisms were identified with an Alcian blue and periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure, B). The organisms demonstrated a vertical orientation in relation to the mucosal surface, which was consistent with candidal organisms.

Given the rapid eruption of these plaques, the distribution on the oral and palmar surfaces (tripe palms), and the minimal improvement with both systemic steroids and antifungal treatment, a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans with secondary candidal infection was made. Drug-induced cheilitis was considered; however, improvement with discontinuation of the suspected offending drug would have been expected. Although chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis was possible, more prompt improvement upon initiation of systemic antifungal therapy would have been observed. Oral Crohn disease should be included in the differential, but it was unlikely given the lack of granulomas on pathology and absence of history of gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome also was unlikely given the lack of facial nerve palsy as well as the lack of granulomas on pathology. Furthermore, none of these options would be associated with tripe palms, as seen in our patient.

Acanthosis nigricans is a localized skin disorder characterized by hyperpigmented velvety plaques arising in flexural and intertriginous regions. Although most cases (80%) are associated with idiopathic or benign conditions, the link between acanthosis nigricans and an underlying malignancy has been well documented.1-3 Most commonly associated with an underlying intra-abdominal malignancy (often gastric carcinoma), the lesions of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans are indistinguishable from their benign counterparts.1,4 When the condition presents abruptly and extensively in a nonobese patient, prompt workup for malignancy should be initiated. Rapid onset and atypical distribution (ie, palmar, perioral, or mucosal) more commonly is associated with a paraneoplastic etiology.5,6

Histopathology for acanthosis nigricans shows hyperkeratosis and epidermal papillomatosis. Horn pseudocyst formation is possible, but usually no hyperpigmentation is observed. The findings typically are indistinguishable from seborrheic keratoses, epidermal nevi, or lesions of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud.2

The underlying pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans is poorly understood. In the benign subtype, insulin resistance commonly has been described. In the paraneoplastic subtype, it is proposed that the tumor produces a transforming growth factor that mimics epidermal growth factor and leads to keratinocyte proliferation.7,8 Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans has the potential to arise at any point of tumor development, further contributing to the diagnostic challenge. Treatment of the skin lesions involves management of the underlying malignancy. Unfortunately, many such malignancies often are at an advanced stage, and subsequent prognosis is poor.2

- Shah A, Jack A, Liu H, et al. Neoplastic/paraneoplastic dermatitis, fasciitis, and panniculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:573-592.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kim EJ. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019:2441-2464.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong WS. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Yu Q, Li XL, Ji G, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue for gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:208.

- Mohrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. Tripe palms and malignant acanthosis nigricans: cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2.

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101.

- Shah A, Jack A, Liu H, et al. Neoplastic/paraneoplastic dermatitis, fasciitis, and panniculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2011;37:573-592.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kim EJ. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019:2441-2464.

- Lee HC, Ker KJ, Chong WS. Oral malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms associated with renal urothelial carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1381-1383.

- Yu Q, Li XL, Ji G, et al. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue for gastric adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:208.

- Mohrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, et al. Tripe palms and malignant acanthosis nigricans: cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629-1630.

- Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, et al. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-678.

- Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2.

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101.

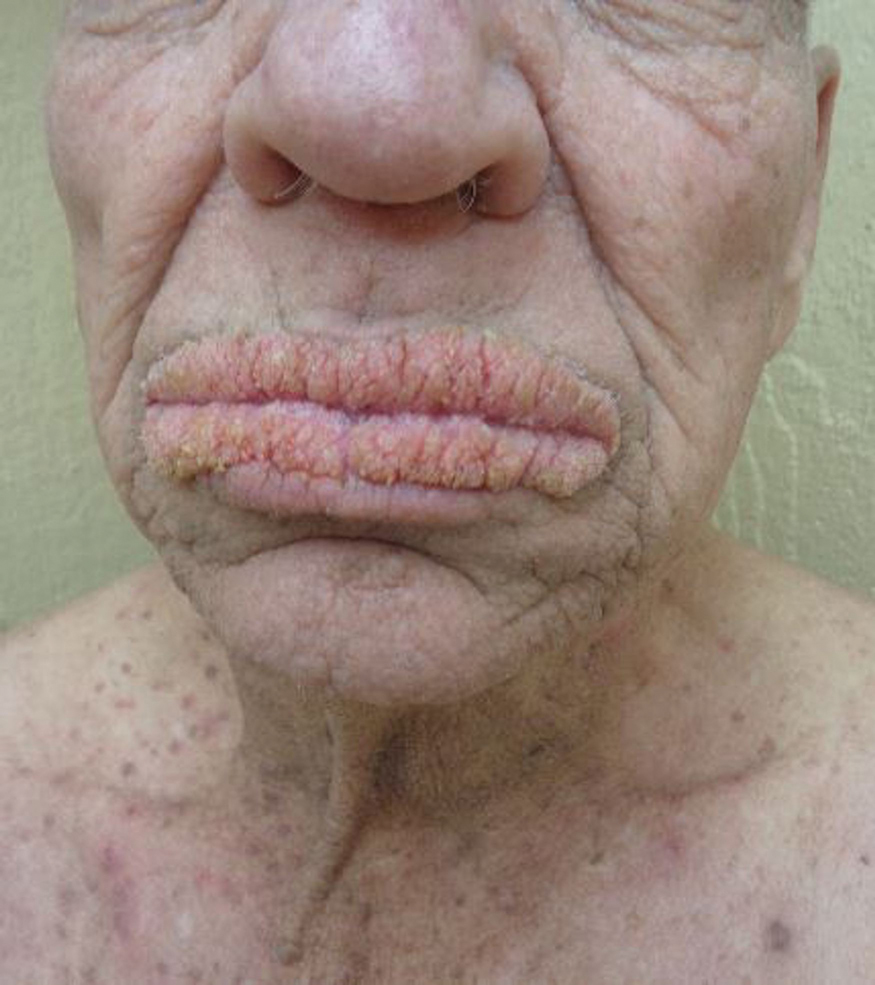

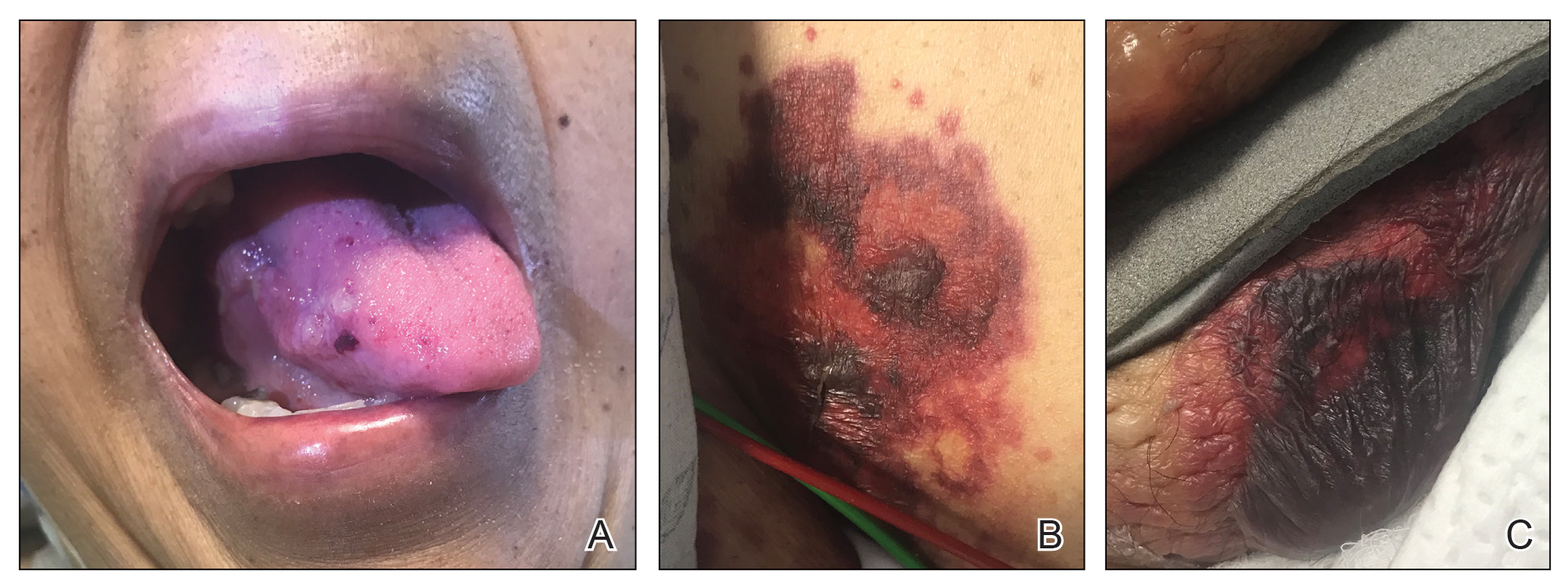

A 75-year-old nonobese man with metastatic urothelial carcinoma presented for evaluation and treatment of swollen lips. The patient stated that his lips began to swell and crack shortly after beginning pembrolizumab approximately 5 months prior. The swelling had progressively worsened, prompting discontinuation of the pembrolizumab by oncology about 2 months prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic. He reported slight improvement after the discontinuation of pembrolizumab, and he had since been started on carboplatin and gemcitabine. He previously was treated with oral corticosteroids without improvement. His oncologist started him on oral fluconazole for treatment of oral thrush on the day of presentation to our clinic. Physical examination revealed diffuse papillomatous and verrucous plaques of the upper and lower lips with involvement of the buccal mucosa. He also had deep fissures and white plaques on the tongue. Velvety hyperpigmented plaques were noted in the axillae, and he had confluent thickening of the palms. A 3-mm punch biopsy from the lower lip was performed. The patient subsequently was evaluated 2 weeks after the initial appointment, and minor improvement in the oral verrucous hyperplasia was noted following antifungal therapy, with resolution of the candidiasis.

Periorbital and Tragal Cutaneous Lesions

The Diagnosis: Favre-Racouchot Syndrome

Favre-Racouchot syndrome, also known as nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones, is seen in approximately 6% of adults aged 40 to 60 years and predominantly is observed in White males.1 Typically, patients have a history of prolonged recreational or occupational UV exposure and tobacco use. The diagnosis can be made clinically; no biopsy is necessary. If a biopsy is performed, histologic findings typically consist of notable actinic elastosis, epidermal atrophy, and comedones. The differential diagnosis includes acne comedones, colloid milium, milia, chloracne, and trichoepithelioma.2 Associated conditions that have been found concurrently include cutis rhomboidalis nuchae, actinic keratosis, erosive pustular dermatosis, actinic granuloma, and basal and squamous cell carcinomas.2

The pathogenesis, while not fully understood, seems to involve a combination of chronic UV radiation exposure and heavy cigarette smoking that eventually leads to cutaneous atrophy and keratinization of the pilosebaceous follicles as well as the formation of comedones.2 Radiation therapy also has been implicated as a possible causative agent of Favre-Racouchot syndrome.1 Clinically, symmetric distribution of large black comedones over the temporal and periorbital areas is seen surrounded by distinct signs of UV-damaged skin, including wrinkles and atrophic skin.3 Although there seems to be a synergistic effect between cigarette smoking and chronic UV exposure, evidence favors smoking as the major cause of this condition,4,5 which causes striking visual changes but is a benign process. UV protection and smoking cessation are the most important factors for prevention and limiting progression.

Treatment consists of typical comedonal therapies such as tretinoin or comedone extraction. Procedural options in conjunction with medical therapy include dermabrasion or laser therapy. Newer studies have shown promising results for both CO2 laser treatment and plasma exeresis.6 Plasma exeresis is a noninvasive technique that causes ionization of atmospheric gas between the device and tissue, ultimately causing sublimation of the target tissue.7 It is important to carefully evaluate and follow up with these patients due to their history of extensive UV exposure. Both short-term and long-term follow-up is recommended due to high rates of reoccurrence within 10 to 12 months and the dangers of chronic UV exposure– related malignancies.6

- Lewis KG, Bercovitch L, Dill SW, et al. Acquired disorders of elastic tissue: part i. increased elastic tissue and solar elastotic syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1-21; quiz 22-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.03.013

- Patterson WM, Fox MD, Schwartz RA. Favre-Racouchot disease. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:167-169. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01546.x

- Sonthalia S, Arora R, Chhabra N, et al. Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 2):S128-S129. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.146192

- Keough GC, Laws RA, Elston DM. Favre-Racouchot syndrome: a case for smokers’ comedones. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:796-797. doi:10.1001/archderm.133.6.796

- Muto H, Takizawa Y. Dioxins in cigarette smoke. Arch Environ Health. 1989;44:171-174. doi:10.1080/00039896.1989.9935882

- Paganelli A, Mandel VD, Kaleci S, et al. Favre-Racouchot disease: systematic review and possible therapeutic strategies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;33:32-41. doi:10.1111/jdv.15184

- Rossi E, Paganelli A, Mandel VD, et al. Plasma exeresis treatment for epidermoid cysts: a minimal scarring technique. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1509-1515. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001604

The Diagnosis: Favre-Racouchot Syndrome

Favre-Racouchot syndrome, also known as nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones, is seen in approximately 6% of adults aged 40 to 60 years and predominantly is observed in White males.1 Typically, patients have a history of prolonged recreational or occupational UV exposure and tobacco use. The diagnosis can be made clinically; no biopsy is necessary. If a biopsy is performed, histologic findings typically consist of notable actinic elastosis, epidermal atrophy, and comedones. The differential diagnosis includes acne comedones, colloid milium, milia, chloracne, and trichoepithelioma.2 Associated conditions that have been found concurrently include cutis rhomboidalis nuchae, actinic keratosis, erosive pustular dermatosis, actinic granuloma, and basal and squamous cell carcinomas.2

The pathogenesis, while not fully understood, seems to involve a combination of chronic UV radiation exposure and heavy cigarette smoking that eventually leads to cutaneous atrophy and keratinization of the pilosebaceous follicles as well as the formation of comedones.2 Radiation therapy also has been implicated as a possible causative agent of Favre-Racouchot syndrome.1 Clinically, symmetric distribution of large black comedones over the temporal and periorbital areas is seen surrounded by distinct signs of UV-damaged skin, including wrinkles and atrophic skin.3 Although there seems to be a synergistic effect between cigarette smoking and chronic UV exposure, evidence favors smoking as the major cause of this condition,4,5 which causes striking visual changes but is a benign process. UV protection and smoking cessation are the most important factors for prevention and limiting progression.

Treatment consists of typical comedonal therapies such as tretinoin or comedone extraction. Procedural options in conjunction with medical therapy include dermabrasion or laser therapy. Newer studies have shown promising results for both CO2 laser treatment and plasma exeresis.6 Plasma exeresis is a noninvasive technique that causes ionization of atmospheric gas between the device and tissue, ultimately causing sublimation of the target tissue.7 It is important to carefully evaluate and follow up with these patients due to their history of extensive UV exposure. Both short-term and long-term follow-up is recommended due to high rates of reoccurrence within 10 to 12 months and the dangers of chronic UV exposure– related malignancies.6

The Diagnosis: Favre-Racouchot Syndrome

Favre-Racouchot syndrome, also known as nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones, is seen in approximately 6% of adults aged 40 to 60 years and predominantly is observed in White males.1 Typically, patients have a history of prolonged recreational or occupational UV exposure and tobacco use. The diagnosis can be made clinically; no biopsy is necessary. If a biopsy is performed, histologic findings typically consist of notable actinic elastosis, epidermal atrophy, and comedones. The differential diagnosis includes acne comedones, colloid milium, milia, chloracne, and trichoepithelioma.2 Associated conditions that have been found concurrently include cutis rhomboidalis nuchae, actinic keratosis, erosive pustular dermatosis, actinic granuloma, and basal and squamous cell carcinomas.2

The pathogenesis, while not fully understood, seems to involve a combination of chronic UV radiation exposure and heavy cigarette smoking that eventually leads to cutaneous atrophy and keratinization of the pilosebaceous follicles as well as the formation of comedones.2 Radiation therapy also has been implicated as a possible causative agent of Favre-Racouchot syndrome.1 Clinically, symmetric distribution of large black comedones over the temporal and periorbital areas is seen surrounded by distinct signs of UV-damaged skin, including wrinkles and atrophic skin.3 Although there seems to be a synergistic effect between cigarette smoking and chronic UV exposure, evidence favors smoking as the major cause of this condition,4,5 which causes striking visual changes but is a benign process. UV protection and smoking cessation are the most important factors for prevention and limiting progression.

Treatment consists of typical comedonal therapies such as tretinoin or comedone extraction. Procedural options in conjunction with medical therapy include dermabrasion or laser therapy. Newer studies have shown promising results for both CO2 laser treatment and plasma exeresis.6 Plasma exeresis is a noninvasive technique that causes ionization of atmospheric gas between the device and tissue, ultimately causing sublimation of the target tissue.7 It is important to carefully evaluate and follow up with these patients due to their history of extensive UV exposure. Both short-term and long-term follow-up is recommended due to high rates of reoccurrence within 10 to 12 months and the dangers of chronic UV exposure– related malignancies.6

- Lewis KG, Bercovitch L, Dill SW, et al. Acquired disorders of elastic tissue: part i. increased elastic tissue and solar elastotic syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1-21; quiz 22-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.03.013

- Patterson WM, Fox MD, Schwartz RA. Favre-Racouchot disease. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:167-169. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01546.x

- Sonthalia S, Arora R, Chhabra N, et al. Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 2):S128-S129. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.146192

- Keough GC, Laws RA, Elston DM. Favre-Racouchot syndrome: a case for smokers’ comedones. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:796-797. doi:10.1001/archderm.133.6.796

- Muto H, Takizawa Y. Dioxins in cigarette smoke. Arch Environ Health. 1989;44:171-174. doi:10.1080/00039896.1989.9935882

- Paganelli A, Mandel VD, Kaleci S, et al. Favre-Racouchot disease: systematic review and possible therapeutic strategies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;33:32-41. doi:10.1111/jdv.15184

- Rossi E, Paganelli A, Mandel VD, et al. Plasma exeresis treatment for epidermoid cysts: a minimal scarring technique. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1509-1515. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001604

- Lewis KG, Bercovitch L, Dill SW, et al. Acquired disorders of elastic tissue: part i. increased elastic tissue and solar elastotic syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1-21; quiz 22-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.03.013

- Patterson WM, Fox MD, Schwartz RA. Favre-Racouchot disease. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:167-169. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01546.x

- Sonthalia S, Arora R, Chhabra N, et al. Favre-Racouchot syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(suppl 2):S128-S129. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.146192

- Keough GC, Laws RA, Elston DM. Favre-Racouchot syndrome: a case for smokers’ comedones. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:796-797. doi:10.1001/archderm.133.6.796

- Muto H, Takizawa Y. Dioxins in cigarette smoke. Arch Environ Health. 1989;44:171-174. doi:10.1080/00039896.1989.9935882

- Paganelli A, Mandel VD, Kaleci S, et al. Favre-Racouchot disease: systematic review and possible therapeutic strategies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;33:32-41. doi:10.1111/jdv.15184

- Rossi E, Paganelli A, Mandel VD, et al. Plasma exeresis treatment for epidermoid cysts: a minimal scarring technique. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1509-1515. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001604

A 91-year-old White man with no personal or family history of skin cancer presented to the dermatology clinic for a total-body skin examination. A 6×5-cm grouped cluster of open comedones in the periorbital region and on the left tragus as well as surrounding actinic damaged skin with coarse rhytides, dyschromia, and lentigines were seen. He had a history of excessive UV exposure and noted that the lesions had been present for approximately 10 years. They were asymptomatic and remained unchanged since their onset.

Multiple Crusted Swellings on the Chin

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Cryptococcosis

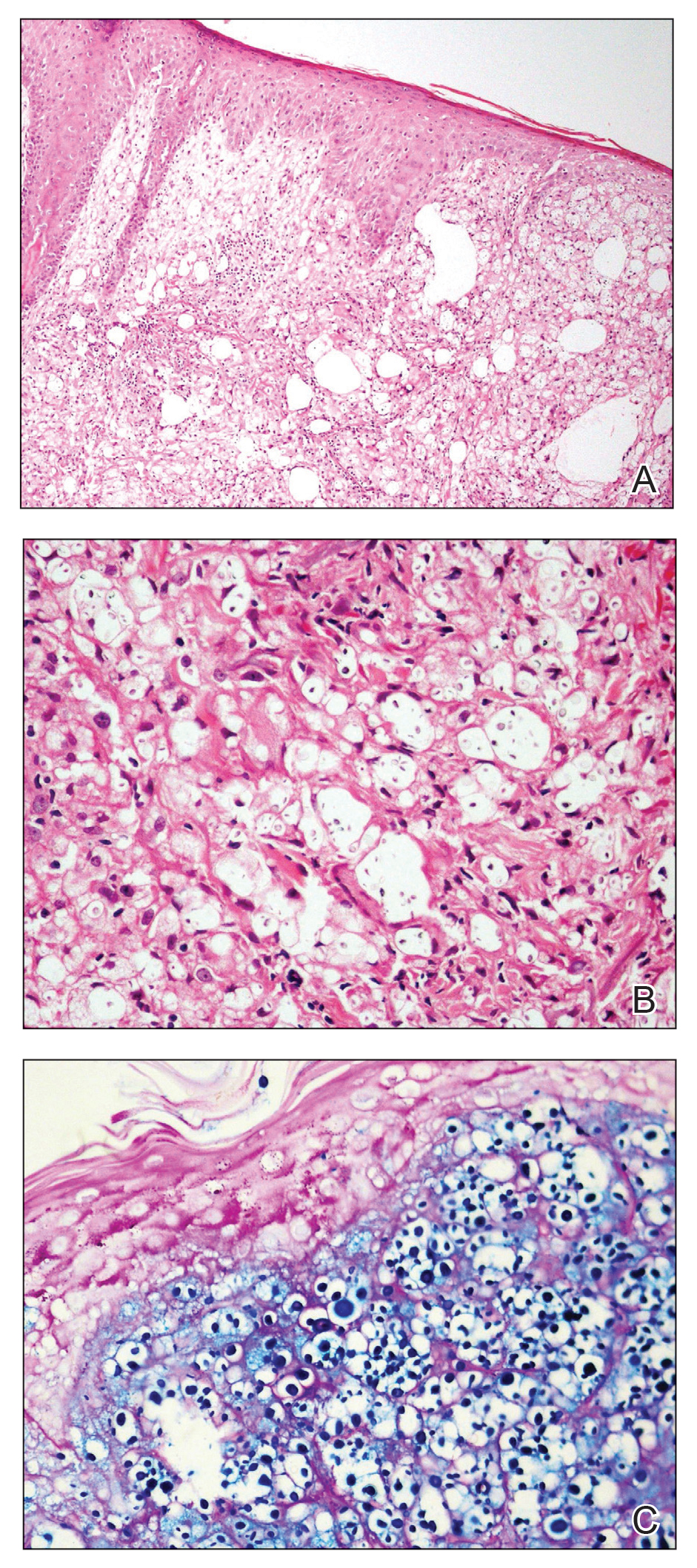

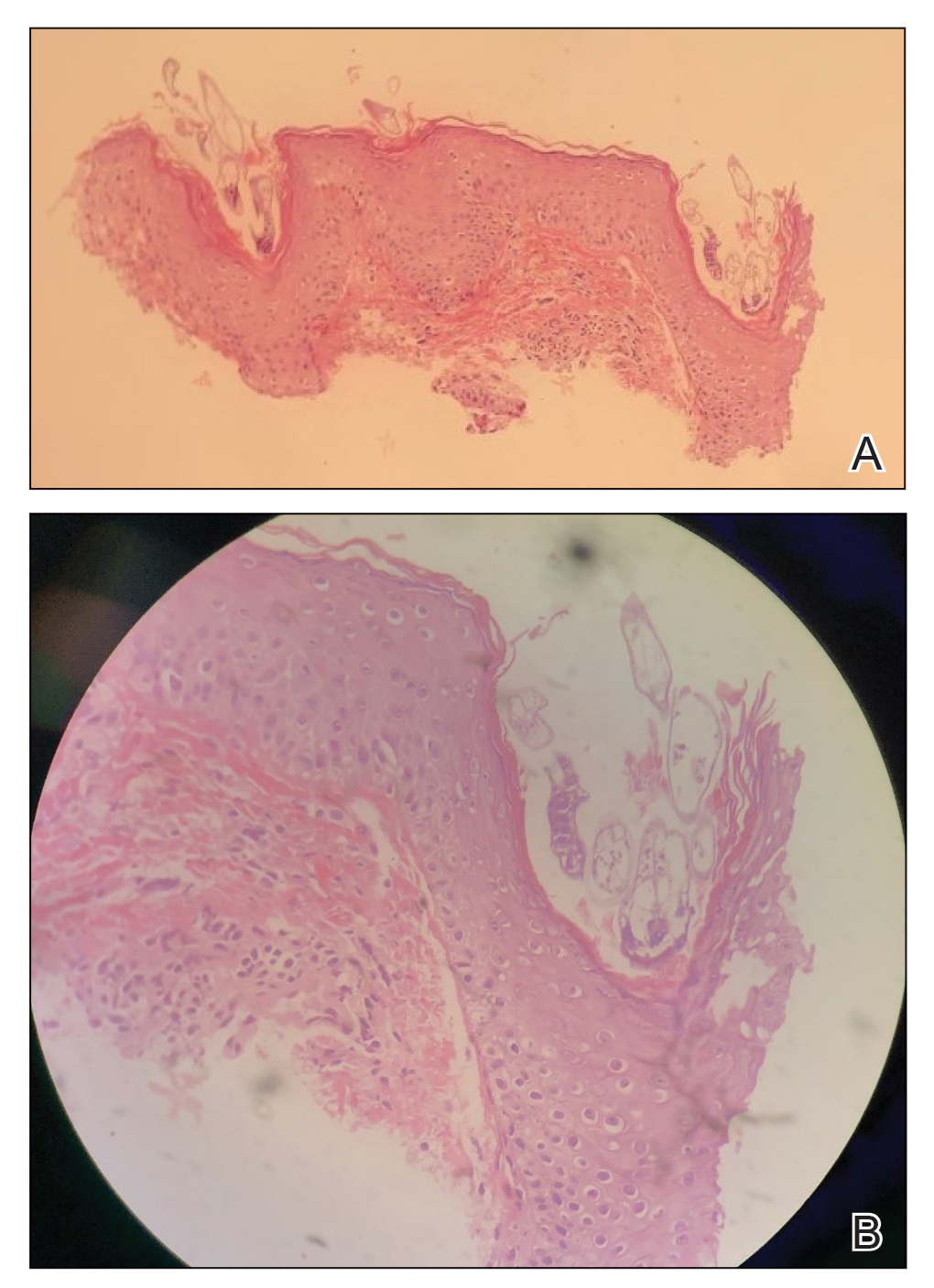

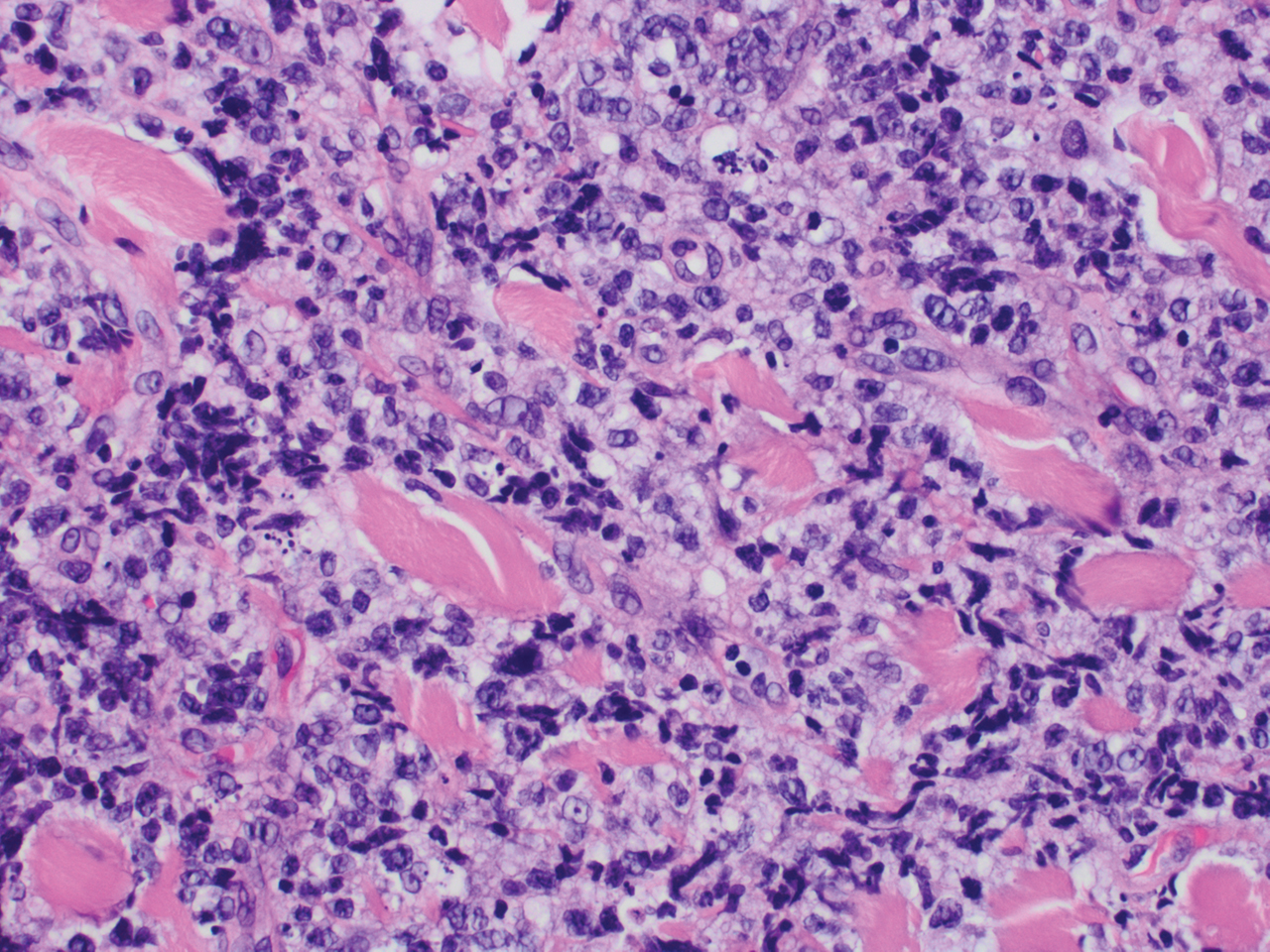

Histologic examination revealed infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with rounded basophilic cells on low magnification (Figure 1A). On higher magnification, encapsulated yeast cells (cryptococci) of varying size accompanied by chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltration with occasional giant cells were seen (Figure 1B). Alcian blue stain showed mucinous capsular material (Figure 1C). There was no history of diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, steroid therapy, or immunosuppression. Moreover, systemic involvement or systemic focus of infection was ruled out after computed tomography of the head, chest, and abdomen. Therefore, the diagnosis of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) was established. The patient was started on oral itraconazole 100 mg twice daily along with 5 drops of a saturated solution of potassium iodide 3 times daily that later was increased to 20 drops 3 times daily at a weekly interval. The lesions started improving after 1 month and healed completely after 9 months of treatment (Figure 2).

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is the identification of Cryptococcus neoformans in a skin lesion without evidence of simultaneous disseminated disease. Neuville et al1 observed that skin lesions resemble cellulitis, ulcerations, or whitlows and were located on unclothed areas. In contrast, lesions from disseminated disease presented as scattered umbilicated papules resembling molluscum contagiosum. Diagnosis of PCC is based on the observation of encapsulated yeasts by direct microscopic examination, isolation of C neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii in culture, and by the demonstration of capsular antigen in various fluids, including serum and cerebrospinal fluid by latex particle agglutination or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Histologically, Cryptococcus species produce a proliferative inflammatory reaction in immunocompetent hosts with the formation of compact epithelioid granulomas, with giant cells and a peripheral layer of lymphocytes. Treatment options for PCC infection range from antifungal medications and surgical debridement to observation.

The differential diagnosis may include cutaneous leishmaniasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, cutaneous histoplasmosis, and basal cell carcinoma. These entities may have similar presentations and can only be confidently differentiated on direct microscopy and histopathologic examination. The characteristic Leishmania donovani bodies on microscopy in cutaneous leishmaniasis and tubercular granuloma with central necrosis on histology in cutaneous tuberculosis can differentiate these conditions from cryptococcosis. In some patients with cryptococcosis, the yeast may produce a less characteristic polysaccharide capsule and thus may be confused with histoplasmosis. Fontana-Masson staining may show melanin-producing yeast, which is characteristic of cryptococci.2 Ulcerated basal cell carcinoma may present similar clinically; however, histopathology will rule it out.

Cutaneous cryptococcal infection should be presumed to be disseminated until proven otherwise, and a search for other sites of involvement must immediately be undertaken. Cutaneous signs may be the first indication of infection, preceding the diagnosis of disseminated disease by 2 to 8 months, making its recognition crucial to early treatment. It is not possible to diagnose PCC on a specific clinical manifestation because a diverse range of skin lesions may be present. Therefore, culture and histology are the gold standards for diagnosis of cryptococcosis.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Cryptococcosis

Histologic examination revealed infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with rounded basophilic cells on low magnification (Figure 1A). On higher magnification, encapsulated yeast cells (cryptococci) of varying size accompanied by chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltration with occasional giant cells were seen (Figure 1B). Alcian blue stain showed mucinous capsular material (Figure 1C). There was no history of diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, steroid therapy, or immunosuppression. Moreover, systemic involvement or systemic focus of infection was ruled out after computed tomography of the head, chest, and abdomen. Therefore, the diagnosis of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) was established. The patient was started on oral itraconazole 100 mg twice daily along with 5 drops of a saturated solution of potassium iodide 3 times daily that later was increased to 20 drops 3 times daily at a weekly interval. The lesions started improving after 1 month and healed completely after 9 months of treatment (Figure 2).

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is the identification of Cryptococcus neoformans in a skin lesion without evidence of simultaneous disseminated disease. Neuville et al1 observed that skin lesions resemble cellulitis, ulcerations, or whitlows and were located on unclothed areas. In contrast, lesions from disseminated disease presented as scattered umbilicated papules resembling molluscum contagiosum. Diagnosis of PCC is based on the observation of encapsulated yeasts by direct microscopic examination, isolation of C neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii in culture, and by the demonstration of capsular antigen in various fluids, including serum and cerebrospinal fluid by latex particle agglutination or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Histologically, Cryptococcus species produce a proliferative inflammatory reaction in immunocompetent hosts with the formation of compact epithelioid granulomas, with giant cells and a peripheral layer of lymphocytes. Treatment options for PCC infection range from antifungal medications and surgical debridement to observation.

The differential diagnosis may include cutaneous leishmaniasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, cutaneous histoplasmosis, and basal cell carcinoma. These entities may have similar presentations and can only be confidently differentiated on direct microscopy and histopathologic examination. The characteristic Leishmania donovani bodies on microscopy in cutaneous leishmaniasis and tubercular granuloma with central necrosis on histology in cutaneous tuberculosis can differentiate these conditions from cryptococcosis. In some patients with cryptococcosis, the yeast may produce a less characteristic polysaccharide capsule and thus may be confused with histoplasmosis. Fontana-Masson staining may show melanin-producing yeast, which is characteristic of cryptococci.2 Ulcerated basal cell carcinoma may present similar clinically; however, histopathology will rule it out.

Cutaneous cryptococcal infection should be presumed to be disseminated until proven otherwise, and a search for other sites of involvement must immediately be undertaken. Cutaneous signs may be the first indication of infection, preceding the diagnosis of disseminated disease by 2 to 8 months, making its recognition crucial to early treatment. It is not possible to diagnose PCC on a specific clinical manifestation because a diverse range of skin lesions may be present. Therefore, culture and histology are the gold standards for diagnosis of cryptococcosis.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Cryptococcosis

Histologic examination revealed infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with rounded basophilic cells on low magnification (Figure 1A). On higher magnification, encapsulated yeast cells (cryptococci) of varying size accompanied by chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltration with occasional giant cells were seen (Figure 1B). Alcian blue stain showed mucinous capsular material (Figure 1C). There was no history of diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, steroid therapy, or immunosuppression. Moreover, systemic involvement or systemic focus of infection was ruled out after computed tomography of the head, chest, and abdomen. Therefore, the diagnosis of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) was established. The patient was started on oral itraconazole 100 mg twice daily along with 5 drops of a saturated solution of potassium iodide 3 times daily that later was increased to 20 drops 3 times daily at a weekly interval. The lesions started improving after 1 month and healed completely after 9 months of treatment (Figure 2).

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is the identification of Cryptococcus neoformans in a skin lesion without evidence of simultaneous disseminated disease. Neuville et al1 observed that skin lesions resemble cellulitis, ulcerations, or whitlows and were located on unclothed areas. In contrast, lesions from disseminated disease presented as scattered umbilicated papules resembling molluscum contagiosum. Diagnosis of PCC is based on the observation of encapsulated yeasts by direct microscopic examination, isolation of C neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii in culture, and by the demonstration of capsular antigen in various fluids, including serum and cerebrospinal fluid by latex particle agglutination or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Histologically, Cryptococcus species produce a proliferative inflammatory reaction in immunocompetent hosts with the formation of compact epithelioid granulomas, with giant cells and a peripheral layer of lymphocytes. Treatment options for PCC infection range from antifungal medications and surgical debridement to observation.

The differential diagnosis may include cutaneous leishmaniasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, cutaneous histoplasmosis, and basal cell carcinoma. These entities may have similar presentations and can only be confidently differentiated on direct microscopy and histopathologic examination. The characteristic Leishmania donovani bodies on microscopy in cutaneous leishmaniasis and tubercular granuloma with central necrosis on histology in cutaneous tuberculosis can differentiate these conditions from cryptococcosis. In some patients with cryptococcosis, the yeast may produce a less characteristic polysaccharide capsule and thus may be confused with histoplasmosis. Fontana-Masson staining may show melanin-producing yeast, which is characteristic of cryptococci.2 Ulcerated basal cell carcinoma may present similar clinically; however, histopathology will rule it out.

Cutaneous cryptococcal infection should be presumed to be disseminated until proven otherwise, and a search for other sites of involvement must immediately be undertaken. Cutaneous signs may be the first indication of infection, preceding the diagnosis of disseminated disease by 2 to 8 months, making its recognition crucial to early treatment. It is not possible to diagnose PCC on a specific clinical manifestation because a diverse range of skin lesions may be present. Therefore, culture and histology are the gold standards for diagnosis of cryptococcosis.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

A 54-year-old man with no comorbidities presented with multiple painless swellings on the left side of the chin of 1 month’s duration that progressively were increasing, both in size and number. He denied any discharge of pus or grains from the lesion, facial trauma, insect bites, or dental procedures. The patient was treated with oral antibiotics for 15 days with no relief at an outside hospital. All routine blood and serologic investigations including viral markers and chest radiography were normal. Bacterial and fungal cultures as well as an acid-fast bacilli culture were negative. Systemic examination was normal, and vitals were within reference range. Mucocutaneous examination revealed multiple nontender small nodules and plaques with yellow-brown to dark brown hemorrhagic crusts with mild perilesional erythema on the left side of the chin extending to the adjacent neck. All mucosal sites were normal, and a biopsy was performed.

Widespread Hyperkeratotic Papules in a Transplant Recipient

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

Trichodysplasia spinulosa has been described in case reports over the last several decades, with its causative virus trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) identified in 2010 by van der Meijden et al.1 Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus in the Polyomaviridae family, among several other known cutaneous polyomaviruses including Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomavirus (HPyV) 6, HPyV7, HPyV10, and possibly HPyV13.2 The primary target of TSPyV is follicular keratinocytes, and it is believed to cause trichodysplasia spinulosa by primary infection rather than by reactivation. Trichodysplasia spinulosa presents in immunosuppressed patients as a folliculocentric eruption of papules with keratinous spines on the face, often with concurrent alopecia, eventually spreading to the trunk and extremities.3 The diagnosis often is clinical, but a biopsy may be performed for histopathologic confirmation. Alternatively, lesional spicules can be painlessly collected manually and submitted for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR).4 The diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa can be difficult due to similarities with other more common conditions such as keratosis pilaris, milia, filiform warts, or lichen spinulosus.

Similar to trichodysplasia spinulosa, keratosis pilaris also presents with folliculocentric and often erythematous papules.5 Keratosis pilaris most frequently affects the posterior upper arms and thighs but also may affect the cheeks, as seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation between the 2 diagnoses can be made on a clinical basis, as keratosis pilaris lacks the characteristic keratinous spines and often spares the central face and nose, locations that commonly are affected in trichodysplasia spinulosa.3

Milia typically appear as white to yellow papules, often on the cheeks, eyelids, nose, and chin.6 Given their predilection for the face, milia can appear similarly to trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation can be made clinically, as milia typically are not as numerous as the spiculed papules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Morphologically, milia will present as smooth, dome-shaped papules as opposed to the keratinous spicules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. The diagnosis of milia can be confirmed by incision and removal of the white chalky keratin core, a feature absent in trichodysplasia spinulosa.

Filiform warts are benign epidermal proliferations caused by human papillomavirus infection that manifest as flesh-colored, verrucous, hyperkeratotic papules.7 They can appear on virtually any skin surface, including the face, and thus may be mistaken for trichodysplasia spinulosa. Close inspection usually will reveal tiny black dots that represent thrombosed capillaries, a feature lacking in trichodysplasia spinulosa. In long-standing lesions or immunocompromised patients, confluent verrucous plaques may develop.8 Diagnosis of filiform warts can be confirmed with biopsy, which will demonstrate a compact stratum corneum, coarse hypergranulosis, and papillomatosis curving inward, while biopsy of a trichodysplasia spinulosa lesion would show polyomavirus infection of the hair follicle and characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies.9

Lichen spinulosus may appear as multiple folliculocentric scaly papules with hairlike horny spines.10 Lichen spinulosus differs from trichodysplasia spinulosa in that it commonly appears on the neck, abdomen, trochanteric region, arms, elbows, or knees. Lichen spinulosus also classically appears as a concrete cluster of papules, often localized to a certain region, in contrast to trichodysplasia spinulosa, which will be widespread, often spreading over time. Finally, clinical history may help differentiate the 2 entities. Lichen spinulosus most often appears in children and adolescents and often has an indolent course, typically resolving during puberty, while trichodysplasia spinulosa is seen in immunocompromised patients.

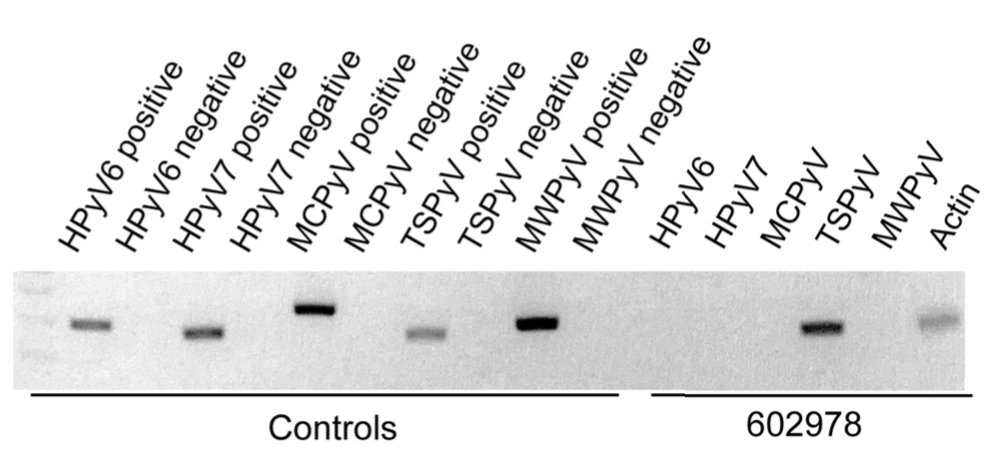

In our patient, the dermatology team made a diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa based on the characteristic clinical presentation, which was confirmed after approximately 10 lesional spicules were removed by tissue forceps and submitted for PCR analysis showing TSPyV (Figure). Two other cases utilized spicule PCR analysis for confirmation of TSPyV.11,12 This technique may represent a viable option for diagnostic confirmation in pediatric cases.

Although some articles have examined the molecular and biologic features of trichodysplasia spinulosa, literature on clinical presentation and management is limited to isolated case reports with no comprehensive studies to establish a standardized treatment. Of these reports, oral valganciclovir 900 mg daily, topical retinoids, cidofovir cream 1% to 3%, and decreasing or altering the immunosuppressive regimen all have been noted to provide clinical improvement.13,14 Other therapies including leflunomide and routine manual extraction of spicules also have shown effectiveness in the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa.15

In our patient, treatment included decreasing immunosuppression, as she was getting recurrent sinus and upper respiratory infections. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was continued solely on tacrolimus therapy. She demonstrated notable improvement after 3 months, with approximately 50% clearance of the eruption. A mutual decision was made at that visit to initiate therapy with compounded cidofovir cream 1% daily to the lesions until the next follow-up visit. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for her scheduled dermatology visits and was lost to long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgment

We thank Richard C. Wang, MD, PhD (Dallas, Texas), for his dermatologic expertise and assistance in analysis of lesional samples for TSPyV.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromised patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Sheu JC, Tran J, Rady PL, et al. Polyomaviruses of the skin: integrating molecular and clinical advances in an emerging class of viruses. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1302-1311.

- Sperling LC, Tomaszewski MM, Thomas DA. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in patients who are immunocompromised. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:318-322.

- Wu JH, Nguyen HP, Rady PL, et al. Molecular insight into the viral biology and clinical features of trichodysplasia spinulosa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:490-498.

- Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- Micali G, Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, et al. Management of cutaneous warts: an evidence-based approach. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:311-317.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

- Chamseddin BH, Tran BAPD, Lee EE, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a child: identification of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in skin, serum, and urine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:723-724.

- Sonstegard A, Grossman M, Garg A. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a kidney transplant recipient. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:105.

- Leitenberger JJ, Abdelmalek M, Wang RC, et al. Two cases of trichodysplasia spinulosa responsive to compounded topical cidofovir 3% cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S33-S35.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Nguyen KD, Chamseddin BH, Cockerell CJ, et al. The biology and clinical features of cutaneous polyomaviruses. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:285-292.

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

Trichodysplasia spinulosa has been described in case reports over the last several decades, with its causative virus trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) identified in 2010 by van der Meijden et al.1 Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus in the Polyomaviridae family, among several other known cutaneous polyomaviruses including Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomavirus (HPyV) 6, HPyV7, HPyV10, and possibly HPyV13.2 The primary target of TSPyV is follicular keratinocytes, and it is believed to cause trichodysplasia spinulosa by primary infection rather than by reactivation. Trichodysplasia spinulosa presents in immunosuppressed patients as a folliculocentric eruption of papules with keratinous spines on the face, often with concurrent alopecia, eventually spreading to the trunk and extremities.3 The diagnosis often is clinical, but a biopsy may be performed for histopathologic confirmation. Alternatively, lesional spicules can be painlessly collected manually and submitted for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR).4 The diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa can be difficult due to similarities with other more common conditions such as keratosis pilaris, milia, filiform warts, or lichen spinulosus.

Similar to trichodysplasia spinulosa, keratosis pilaris also presents with folliculocentric and often erythematous papules.5 Keratosis pilaris most frequently affects the posterior upper arms and thighs but also may affect the cheeks, as seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation between the 2 diagnoses can be made on a clinical basis, as keratosis pilaris lacks the characteristic keratinous spines and often spares the central face and nose, locations that commonly are affected in trichodysplasia spinulosa.3

Milia typically appear as white to yellow papules, often on the cheeks, eyelids, nose, and chin.6 Given their predilection for the face, milia can appear similarly to trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation can be made clinically, as milia typically are not as numerous as the spiculed papules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Morphologically, milia will present as smooth, dome-shaped papules as opposed to the keratinous spicules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. The diagnosis of milia can be confirmed by incision and removal of the white chalky keratin core, a feature absent in trichodysplasia spinulosa.

Filiform warts are benign epidermal proliferations caused by human papillomavirus infection that manifest as flesh-colored, verrucous, hyperkeratotic papules.7 They can appear on virtually any skin surface, including the face, and thus may be mistaken for trichodysplasia spinulosa. Close inspection usually will reveal tiny black dots that represent thrombosed capillaries, a feature lacking in trichodysplasia spinulosa. In long-standing lesions or immunocompromised patients, confluent verrucous plaques may develop.8 Diagnosis of filiform warts can be confirmed with biopsy, which will demonstrate a compact stratum corneum, coarse hypergranulosis, and papillomatosis curving inward, while biopsy of a trichodysplasia spinulosa lesion would show polyomavirus infection of the hair follicle and characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies.9

Lichen spinulosus may appear as multiple folliculocentric scaly papules with hairlike horny spines.10 Lichen spinulosus differs from trichodysplasia spinulosa in that it commonly appears on the neck, abdomen, trochanteric region, arms, elbows, or knees. Lichen spinulosus also classically appears as a concrete cluster of papules, often localized to a certain region, in contrast to trichodysplasia spinulosa, which will be widespread, often spreading over time. Finally, clinical history may help differentiate the 2 entities. Lichen spinulosus most often appears in children and adolescents and often has an indolent course, typically resolving during puberty, while trichodysplasia spinulosa is seen in immunocompromised patients.

In our patient, the dermatology team made a diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa based on the characteristic clinical presentation, which was confirmed after approximately 10 lesional spicules were removed by tissue forceps and submitted for PCR analysis showing TSPyV (Figure). Two other cases utilized spicule PCR analysis for confirmation of TSPyV.11,12 This technique may represent a viable option for diagnostic confirmation in pediatric cases.

Although some articles have examined the molecular and biologic features of trichodysplasia spinulosa, literature on clinical presentation and management is limited to isolated case reports with no comprehensive studies to establish a standardized treatment. Of these reports, oral valganciclovir 900 mg daily, topical retinoids, cidofovir cream 1% to 3%, and decreasing or altering the immunosuppressive regimen all have been noted to provide clinical improvement.13,14 Other therapies including leflunomide and routine manual extraction of spicules also have shown effectiveness in the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa.15

In our patient, treatment included decreasing immunosuppression, as she was getting recurrent sinus and upper respiratory infections. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was continued solely on tacrolimus therapy. She demonstrated notable improvement after 3 months, with approximately 50% clearance of the eruption. A mutual decision was made at that visit to initiate therapy with compounded cidofovir cream 1% daily to the lesions until the next follow-up visit. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for her scheduled dermatology visits and was lost to long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgment

We thank Richard C. Wang, MD, PhD (Dallas, Texas), for his dermatologic expertise and assistance in analysis of lesional samples for TSPyV.

The Diagnosis: Trichodysplasia Spinulosa

Trichodysplasia spinulosa has been described in case reports over the last several decades, with its causative virus trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus (TSPyV) identified in 2010 by van der Meijden et al.1 Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus in the Polyomaviridae family, among several other known cutaneous polyomaviruses including Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomavirus (HPyV) 6, HPyV7, HPyV10, and possibly HPyV13.2 The primary target of TSPyV is follicular keratinocytes, and it is believed to cause trichodysplasia spinulosa by primary infection rather than by reactivation. Trichodysplasia spinulosa presents in immunosuppressed patients as a folliculocentric eruption of papules with keratinous spines on the face, often with concurrent alopecia, eventually spreading to the trunk and extremities.3 The diagnosis often is clinical, but a biopsy may be performed for histopathologic confirmation. Alternatively, lesional spicules can be painlessly collected manually and submitted for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR).4 The diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa can be difficult due to similarities with other more common conditions such as keratosis pilaris, milia, filiform warts, or lichen spinulosus.

Similar to trichodysplasia spinulosa, keratosis pilaris also presents with folliculocentric and often erythematous papules.5 Keratosis pilaris most frequently affects the posterior upper arms and thighs but also may affect the cheeks, as seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation between the 2 diagnoses can be made on a clinical basis, as keratosis pilaris lacks the characteristic keratinous spines and often spares the central face and nose, locations that commonly are affected in trichodysplasia spinulosa.3

Milia typically appear as white to yellow papules, often on the cheeks, eyelids, nose, and chin.6 Given their predilection for the face, milia can appear similarly to trichodysplasia spinulosa. Differentiation can be made clinically, as milia typically are not as numerous as the spiculed papules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. Morphologically, milia will present as smooth, dome-shaped papules as opposed to the keratinous spicules seen in trichodysplasia spinulosa. The diagnosis of milia can be confirmed by incision and removal of the white chalky keratin core, a feature absent in trichodysplasia spinulosa.

Filiform warts are benign epidermal proliferations caused by human papillomavirus infection that manifest as flesh-colored, verrucous, hyperkeratotic papules.7 They can appear on virtually any skin surface, including the face, and thus may be mistaken for trichodysplasia spinulosa. Close inspection usually will reveal tiny black dots that represent thrombosed capillaries, a feature lacking in trichodysplasia spinulosa. In long-standing lesions or immunocompromised patients, confluent verrucous plaques may develop.8 Diagnosis of filiform warts can be confirmed with biopsy, which will demonstrate a compact stratum corneum, coarse hypergranulosis, and papillomatosis curving inward, while biopsy of a trichodysplasia spinulosa lesion would show polyomavirus infection of the hair follicle and characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies.9

Lichen spinulosus may appear as multiple folliculocentric scaly papules with hairlike horny spines.10 Lichen spinulosus differs from trichodysplasia spinulosa in that it commonly appears on the neck, abdomen, trochanteric region, arms, elbows, or knees. Lichen spinulosus also classically appears as a concrete cluster of papules, often localized to a certain region, in contrast to trichodysplasia spinulosa, which will be widespread, often spreading over time. Finally, clinical history may help differentiate the 2 entities. Lichen spinulosus most often appears in children and adolescents and often has an indolent course, typically resolving during puberty, while trichodysplasia spinulosa is seen in immunocompromised patients.

In our patient, the dermatology team made a diagnosis of trichodysplasia spinulosa based on the characteristic clinical presentation, which was confirmed after approximately 10 lesional spicules were removed by tissue forceps and submitted for PCR analysis showing TSPyV (Figure). Two other cases utilized spicule PCR analysis for confirmation of TSPyV.11,12 This technique may represent a viable option for diagnostic confirmation in pediatric cases.

Although some articles have examined the molecular and biologic features of trichodysplasia spinulosa, literature on clinical presentation and management is limited to isolated case reports with no comprehensive studies to establish a standardized treatment. Of these reports, oral valganciclovir 900 mg daily, topical retinoids, cidofovir cream 1% to 3%, and decreasing or altering the immunosuppressive regimen all have been noted to provide clinical improvement.13,14 Other therapies including leflunomide and routine manual extraction of spicules also have shown effectiveness in the treatment of trichodysplasia spinulosa.15

In our patient, treatment included decreasing immunosuppression, as she was getting recurrent sinus and upper respiratory infections. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and the patient was continued solely on tacrolimus therapy. She demonstrated notable improvement after 3 months, with approximately 50% clearance of the eruption. A mutual decision was made at that visit to initiate therapy with compounded cidofovir cream 1% daily to the lesions until the next follow-up visit. Unfortunately, the patient did not return for her scheduled dermatology visits and was lost to long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgment

We thank Richard C. Wang, MD, PhD (Dallas, Texas), for his dermatologic expertise and assistance in analysis of lesional samples for TSPyV.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromised patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Sheu JC, Tran J, Rady PL, et al. Polyomaviruses of the skin: integrating molecular and clinical advances in an emerging class of viruses. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1302-1311.

- Sperling LC, Tomaszewski MM, Thomas DA. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in patients who are immunocompromised. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:318-322.

- Wu JH, Nguyen HP, Rady PL, et al. Molecular insight into the viral biology and clinical features of trichodysplasia spinulosa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:490-498.

- Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- Micali G, Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, et al. Management of cutaneous warts: an evidence-based approach. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:311-317.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

- Chamseddin BH, Tran BAPD, Lee EE, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a child: identification of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in skin, serum, and urine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:723-724.

- Sonstegard A, Grossman M, Garg A. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a kidney transplant recipient. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:105.

- Leitenberger JJ, Abdelmalek M, Wang RC, et al. Two cases of trichodysplasia spinulosa responsive to compounded topical cidofovir 3% cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S33-S35.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Nguyen KD, Chamseddin BH, Cockerell CJ, et al. The biology and clinical features of cutaneous polyomaviruses. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:285-292.

- van der Meijden E, Janssens RWA, Lauber C, et al. Discovery of a new human polyomavirus associated with trichodysplasia spinulosa in an immunocompromised patient. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:E1001024.

- Sheu JC, Tran J, Rady PL, et al. Polyomaviruses of the skin: integrating molecular and clinical advances in an emerging class of viruses. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1302-1311.

- Sperling LC, Tomaszewski MM, Thomas DA. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in patients who are immunocompromised. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:318-322.

- Wu JH, Nguyen HP, Rady PL, et al. Molecular insight into the viral biology and clinical features of trichodysplasia spinulosa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:490-498.

- Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: a common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177-180.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- Micali G, Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, et al. Management of cutaneous warts: an evidence-based approach. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:311-317.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

- Chamseddin BH, Tran BAPD, Lee EE, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a child: identification of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in skin, serum, and urine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:723-724.

- Sonstegard A, Grossman M, Garg A. Trichodysplasia spinulosa in a kidney transplant recipient. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:105.

- Leitenberger JJ, Abdelmalek M, Wang RC, et al. Two cases of trichodysplasia spinulosa responsive to compounded topical cidofovir 3% cream. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S33-S35.

- DeCrescenzo AJ, Philips RC, Wilkerson MG. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: a rare complication of immunosuppression. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:307-309.

- Nguyen KD, Chamseddin BH, Cockerell CJ, et al. The biology and clinical features of cutaneous polyomaviruses. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:285-292.

A 4-year-old girl with a history of cardiac transplantation 1 year prior for dilated cardiomyopathy presented to the dermatology consultation service with widespread hyperkeratotic papules of 2 months’ duration. The eruption initially had appeared on the face with subsequent involvement of the trunk and extremities. Her immunosuppressive medications included oral tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. No over-the-counter or prescription treatments had been used for the eruption; the patient’s mother had been manually extracting the spicules from the nose, cheeks, and forehead with tweezers. The lesions were asymptomatic with only mild follicular erythema. Physical examination revealed multiple folliculocentric keratinous spicules on the nose, cheeks, forehead (top), trunk (bottom), arms, and legs.

Nodule on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

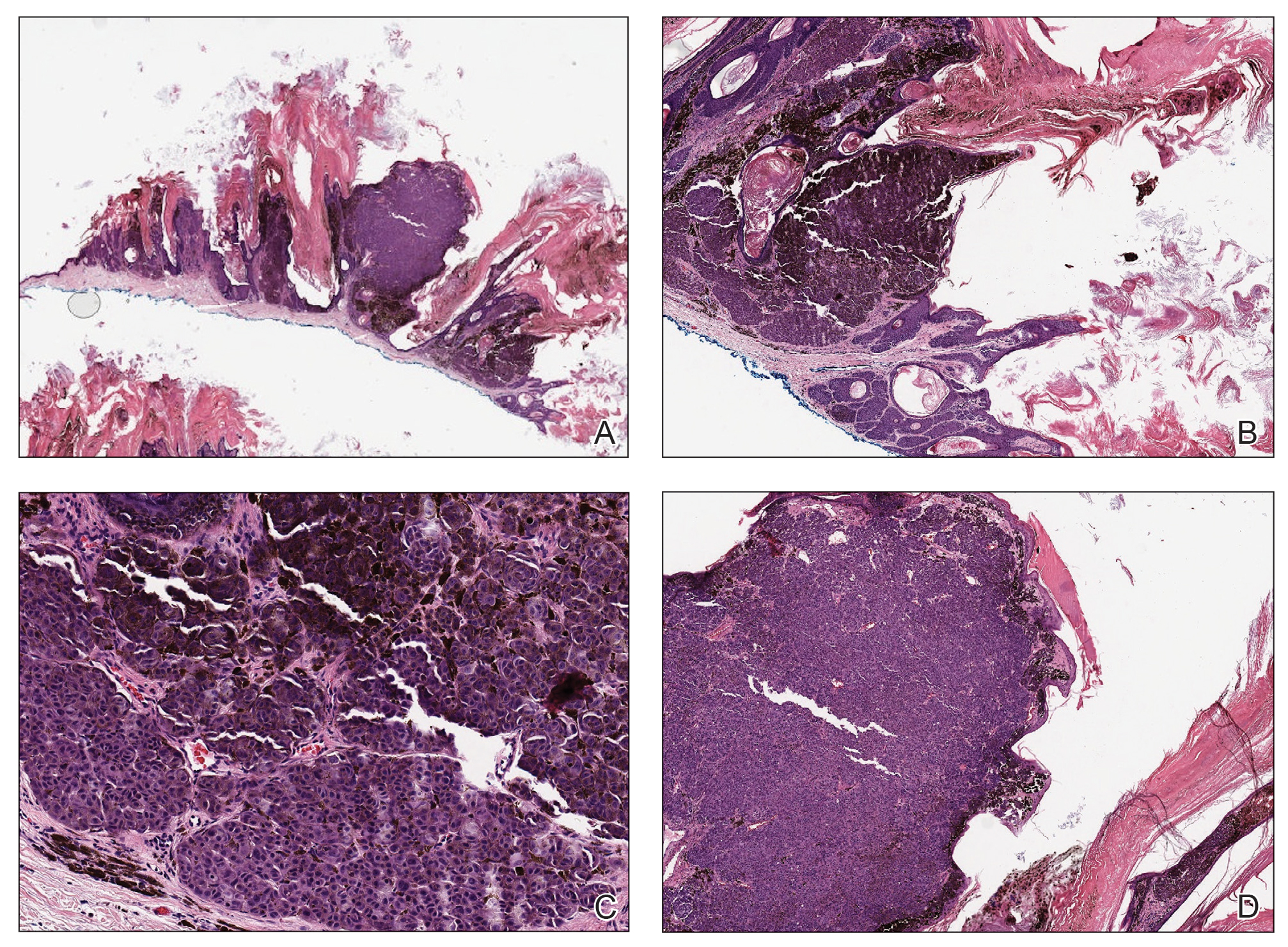

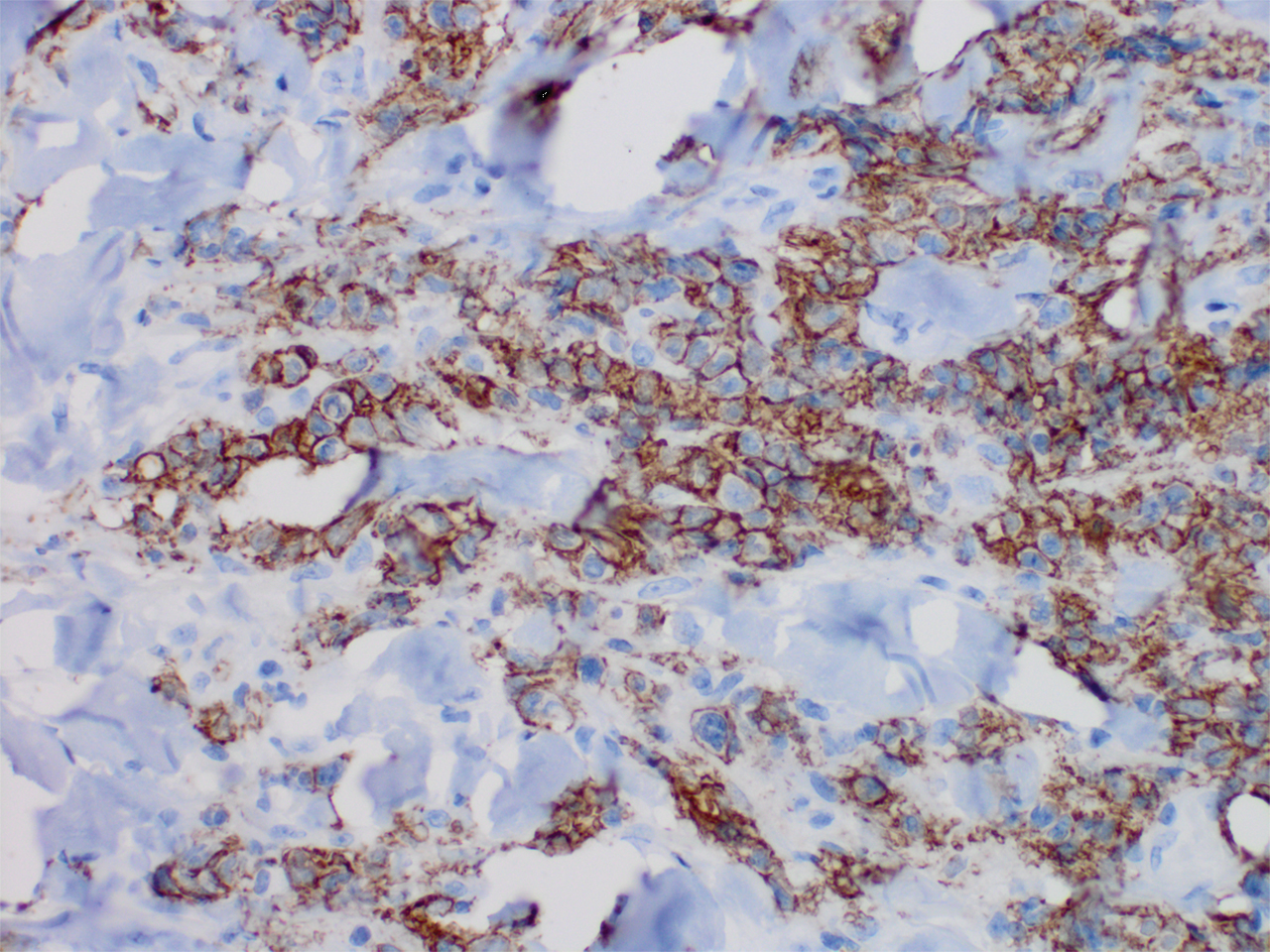

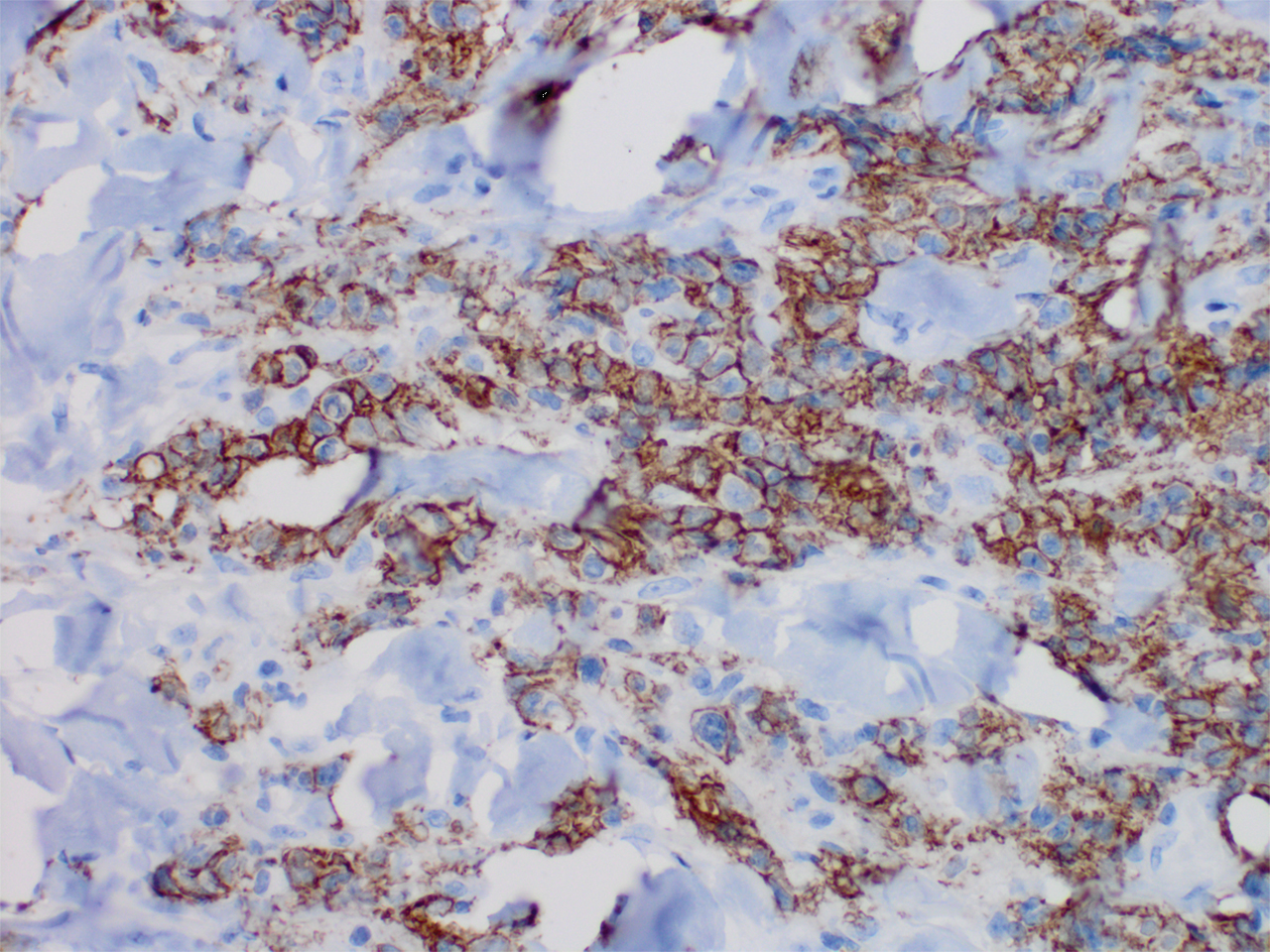

Microscopic analysis showed a dense proliferation of mononuclear cells filling and expanding the dermis with focal epidermotropism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong and diffuse staining for CD3, CD4, and CD30 (Figure 2) and lack of staining for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Workup to exclude systemic disease was initiated and included unremarkable computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis along with no abnormal cells on bone marrow biopsy. Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range. Given the lack of evidence for systemic involvement, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) was made. The treatment plan for our patient with a solitary lesion was localized radiation therapy.

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders encompass a spectrum of conditions, with premalignant lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) at one extreme and the malignant PC-ALCL on the other.1 The diagnosis of PC-ALCL is made by clinicopathologic correlation, and lesions typically present abruptly as solitary or grouped nodules with a tendency to ulcerate over time. Spontaneous regression has been reported, but relapse in the skin is frequent.2

A representative, typically excisional, biopsy should be performed if the clinician suspects PC-ALCL. Histologic criteria include a dense dermal infiltrate of large pleomorphic cells and the expression of CD30 in at least 75% of tumor cells.3 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma typically lacks the ALK gene translocation with the nucleophosmin gene, NPM, that is common in systemic disease; however, a small subset of PC-ALCL may be ALK positive and indicate a higher chance of transformation into systemic disease.2

The extent of the lymphoma should be staged to exclude the possibility of systemic disease. This assessment includes a complete physical examination; laboratory investigation, including complete blood cell count with differential and blood chemistries; and radiography. A positron emission tomography-CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or a whole-body integrated positron emission tomography-CT are sufficient for the radiographic examination.3

The initial choice of treatment for solitary or localized PC-ALCL is localized radiation therapy or low-dose methotrexate. Targeted therapy such as brentuximab has been shown to be effective for those with multifocal systemic involvement or refractory disease.2 Cure rates from radiation therapy alone approach 95%.3 It is important to highlight radiation therapy as the initial management plan to increase awareness and to avoid inappropriate treatment of PC-ALCL with traditional chemotherapy.

Large lesions of LyP may appear similar to PC-ALCL on histopathology, making the two entities difficult to distinguish. However, in contrast to PC-ALCL, LyP classically has a different clinical course characterized by waxing and waning crops of lesions that typically are smaller (<1 cm) than those of PC-ALCL.2 Large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides is another entity to consider, but these patients usually have a known history of mycosis fungoides.4

Keratoacanthomas, considered to be a variant of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, present as rapidly enlarging crateriform nodules with a keratotic core. They usually are found on the head and neck or sun-exposed areas of the extremities and may regress spontaneously.5 Histology will show atypical, highly differentiated squamous epithelia. Merkel cell carcinoma also has a predilection for the head and neck in older patients and may present as a rapidly growing nodule. However, histology will show an aggressive tumor with small round blue cells, and immunohistochemistry will show the characteristic paranuclear dot staining for CK20 along with staining for various neuroendocrine markers. Similarly, atypical fibroxanthoma is a low-grade sarcoma that also presents on the head and neck of elderly sun-damaged patients.5 Histology will show dermal proliferation of spindle cells that often extend up against the epidermis along with pleomorphism and atypical mitoses. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor that can present on the head and neck in sun-damaged patients. Nodular basal cell carcinomas can enlarge and ulcerate, but growth is seen over years rather than weeks.5 Histology characteristically will show tumor islands composed of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and clefting between the tumor islands and the stroma.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Brown RA, Fernandez-Pol S, Kim J. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:570-577.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-17.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2015:475-489.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Microscopic analysis showed a dense proliferation of mononuclear cells filling and expanding the dermis with focal epidermotropism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong and diffuse staining for CD3, CD4, and CD30 (Figure 2) and lack of staining for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Workup to exclude systemic disease was initiated and included unremarkable computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis along with no abnormal cells on bone marrow biopsy. Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range. Given the lack of evidence for systemic involvement, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) was made. The treatment plan for our patient with a solitary lesion was localized radiation therapy.

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders encompass a spectrum of conditions, with premalignant lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) at one extreme and the malignant PC-ALCL on the other.1 The diagnosis of PC-ALCL is made by clinicopathologic correlation, and lesions typically present abruptly as solitary or grouped nodules with a tendency to ulcerate over time. Spontaneous regression has been reported, but relapse in the skin is frequent.2

A representative, typically excisional, biopsy should be performed if the clinician suspects PC-ALCL. Histologic criteria include a dense dermal infiltrate of large pleomorphic cells and the expression of CD30 in at least 75% of tumor cells.3 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma typically lacks the ALK gene translocation with the nucleophosmin gene, NPM, that is common in systemic disease; however, a small subset of PC-ALCL may be ALK positive and indicate a higher chance of transformation into systemic disease.2

The extent of the lymphoma should be staged to exclude the possibility of systemic disease. This assessment includes a complete physical examination; laboratory investigation, including complete blood cell count with differential and blood chemistries; and radiography. A positron emission tomography-CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or a whole-body integrated positron emission tomography-CT are sufficient for the radiographic examination.3

The initial choice of treatment for solitary or localized PC-ALCL is localized radiation therapy or low-dose methotrexate. Targeted therapy such as brentuximab has been shown to be effective for those with multifocal systemic involvement or refractory disease.2 Cure rates from radiation therapy alone approach 95%.3 It is important to highlight radiation therapy as the initial management plan to increase awareness and to avoid inappropriate treatment of PC-ALCL with traditional chemotherapy.

Large lesions of LyP may appear similar to PC-ALCL on histopathology, making the two entities difficult to distinguish. However, in contrast to PC-ALCL, LyP classically has a different clinical course characterized by waxing and waning crops of lesions that typically are smaller (<1 cm) than those of PC-ALCL.2 Large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides is another entity to consider, but these patients usually have a known history of mycosis fungoides.4

Keratoacanthomas, considered to be a variant of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, present as rapidly enlarging crateriform nodules with a keratotic core. They usually are found on the head and neck or sun-exposed areas of the extremities and may regress spontaneously.5 Histology will show atypical, highly differentiated squamous epithelia. Merkel cell carcinoma also has a predilection for the head and neck in older patients and may present as a rapidly growing nodule. However, histology will show an aggressive tumor with small round blue cells, and immunohistochemistry will show the characteristic paranuclear dot staining for CK20 along with staining for various neuroendocrine markers. Similarly, atypical fibroxanthoma is a low-grade sarcoma that also presents on the head and neck of elderly sun-damaged patients.5 Histology will show dermal proliferation of spindle cells that often extend up against the epidermis along with pleomorphism and atypical mitoses. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor that can present on the head and neck in sun-damaged patients. Nodular basal cell carcinomas can enlarge and ulcerate, but growth is seen over years rather than weeks.5 Histology characteristically will show tumor islands composed of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and clefting between the tumor islands and the stroma.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Microscopic analysis showed a dense proliferation of mononuclear cells filling and expanding the dermis with focal epidermotropism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong and diffuse staining for CD3, CD4, and CD30 (Figure 2) and lack of staining for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Workup to exclude systemic disease was initiated and included unremarkable computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis along with no abnormal cells on bone marrow biopsy. Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range. Given the lack of evidence for systemic involvement, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) was made. The treatment plan for our patient with a solitary lesion was localized radiation therapy.

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders encompass a spectrum of conditions, with premalignant lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) at one extreme and the malignant PC-ALCL on the other.1 The diagnosis of PC-ALCL is made by clinicopathologic correlation, and lesions typically present abruptly as solitary or grouped nodules with a tendency to ulcerate over time. Spontaneous regression has been reported, but relapse in the skin is frequent.2

A representative, typically excisional, biopsy should be performed if the clinician suspects PC-ALCL. Histologic criteria include a dense dermal infiltrate of large pleomorphic cells and the expression of CD30 in at least 75% of tumor cells.3 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma typically lacks the ALK gene translocation with the nucleophosmin gene, NPM, that is common in systemic disease; however, a small subset of PC-ALCL may be ALK positive and indicate a higher chance of transformation into systemic disease.2

The extent of the lymphoma should be staged to exclude the possibility of systemic disease. This assessment includes a complete physical examination; laboratory investigation, including complete blood cell count with differential and blood chemistries; and radiography. A positron emission tomography-CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or a whole-body integrated positron emission tomography-CT are sufficient for the radiographic examination.3

The initial choice of treatment for solitary or localized PC-ALCL is localized radiation therapy or low-dose methotrexate. Targeted therapy such as brentuximab has been shown to be effective for those with multifocal systemic involvement or refractory disease.2 Cure rates from radiation therapy alone approach 95%.3 It is important to highlight radiation therapy as the initial management plan to increase awareness and to avoid inappropriate treatment of PC-ALCL with traditional chemotherapy.

Large lesions of LyP may appear similar to PC-ALCL on histopathology, making the two entities difficult to distinguish. However, in contrast to PC-ALCL, LyP classically has a different clinical course characterized by waxing and waning crops of lesions that typically are smaller (<1 cm) than those of PC-ALCL.2 Large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides is another entity to consider, but these patients usually have a known history of mycosis fungoides.4

Keratoacanthomas, considered to be a variant of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, present as rapidly enlarging crateriform nodules with a keratotic core. They usually are found on the head and neck or sun-exposed areas of the extremities and may regress spontaneously.5 Histology will show atypical, highly differentiated squamous epithelia. Merkel cell carcinoma also has a predilection for the head and neck in older patients and may present as a rapidly growing nodule. However, histology will show an aggressive tumor with small round blue cells, and immunohistochemistry will show the characteristic paranuclear dot staining for CK20 along with staining for various neuroendocrine markers. Similarly, atypical fibroxanthoma is a low-grade sarcoma that also presents on the head and neck of elderly sun-damaged patients.5 Histology will show dermal proliferation of spindle cells that often extend up against the epidermis along with pleomorphism and atypical mitoses. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor that can present on the head and neck in sun-damaged patients. Nodular basal cell carcinomas can enlarge and ulcerate, but growth is seen over years rather than weeks.5 Histology characteristically will show tumor islands composed of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and clefting between the tumor islands and the stroma.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Brown RA, Fernandez-Pol S, Kim J. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:570-577.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-17.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2015:475-489.