User login

Symptoms of psychosis and OCD in a patient with postpartum depression

CASE Thoughts of harming baby

Ms. A, age 37, is G4P2, 4 months postpartum, and breastfeeding. She has major depressive disorder (MDD) with peripartum onset, posttraumatic stress disorder, and mild intellectual disability. For years she has been stable on fluoxetine 40 mg/d and prazosin 2 mg/d. Despite recent titration of her medications, at her most recent outpatient appointment Ms. A reports having a depressed mood with frequent crying, insomnia, a lack of desire to bond with her baby, and feelings of shame. She also says she has had auditory hallucinations and thoughts of harming her baby. Ms. A’s outpatient physician makes an urgent request for her to be evaluated at the psychiatric emergency department (ED).

HISTORY Depression and possible auditory hallucinations

Ms. A developed MDD following the birth of her first child, for which her care team initiated fluoxetine at 20 mg/d and titrated it to 40 mg/d,which was effective. At that time, her outpatient physician documented potential psychotic features, including vague descriptions of derogatory auditory hallucinations. However, it was unclear if these auditory hallucinations were more representative of a distressing inner monologue without the quality of an external voice. The team determined that Ms. A was not at acute risk for harm to herself or her baby and was appropriate for outpatient care. Because the nature of these possible auditory hallucinations was mild, nondistressing, and nonthreatening, the treatment team did not initiate an antipsychotic and Ms. A was not hospitalized. She has no history of hypomanic/manic episodes and has never met criteria for a psychotic disorder.

EVALUATION Distressing thoughts and discontinued medications

During the evaluation by psychiatric emergency services, Ms. A reports that 2 weeks after giving birth she experienced a worsening of her depressive symptoms. She says she began hearing voices telling her to harm herself and her baby and describes frequent distressing thoughts, such as stabbing her baby with a knife and running over her baby with a car. Ms. A says she repeatedly wakes up at night to check on her baby’s breathing, overfeeds her baby due to a fear of inadequate nutrition, and notes intermittent feelings of confusion. Afraid of being alone with her infant, Ms. A asks her partner and mother to move in with her. Additionally, she says 2 weeks ago she discontinued all her medications at the suggestion of her partner, who recommended herbal supplements. Ms. A’s initial routine laboratory results are unremarkable and her urine drug screen is negative for all substances.

[polldaddy:13041928]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 85% of birthing parents experience some form of postpartum mood disturbance; 10% to 15% develop more significant symptoms of anxiety or depression.3 The etiology of postpartum illness is multifactorial, and includes psychiatric personal/family history, insomnia, acute and chronic psychosocial stressors, and rapid hormone fluctuations.1 As a result, the postpartum period represents a vulnerable time for birthing parents, particularly those with previously established psychiatric illness.

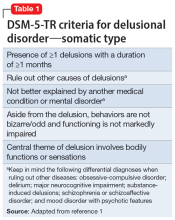

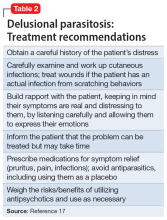

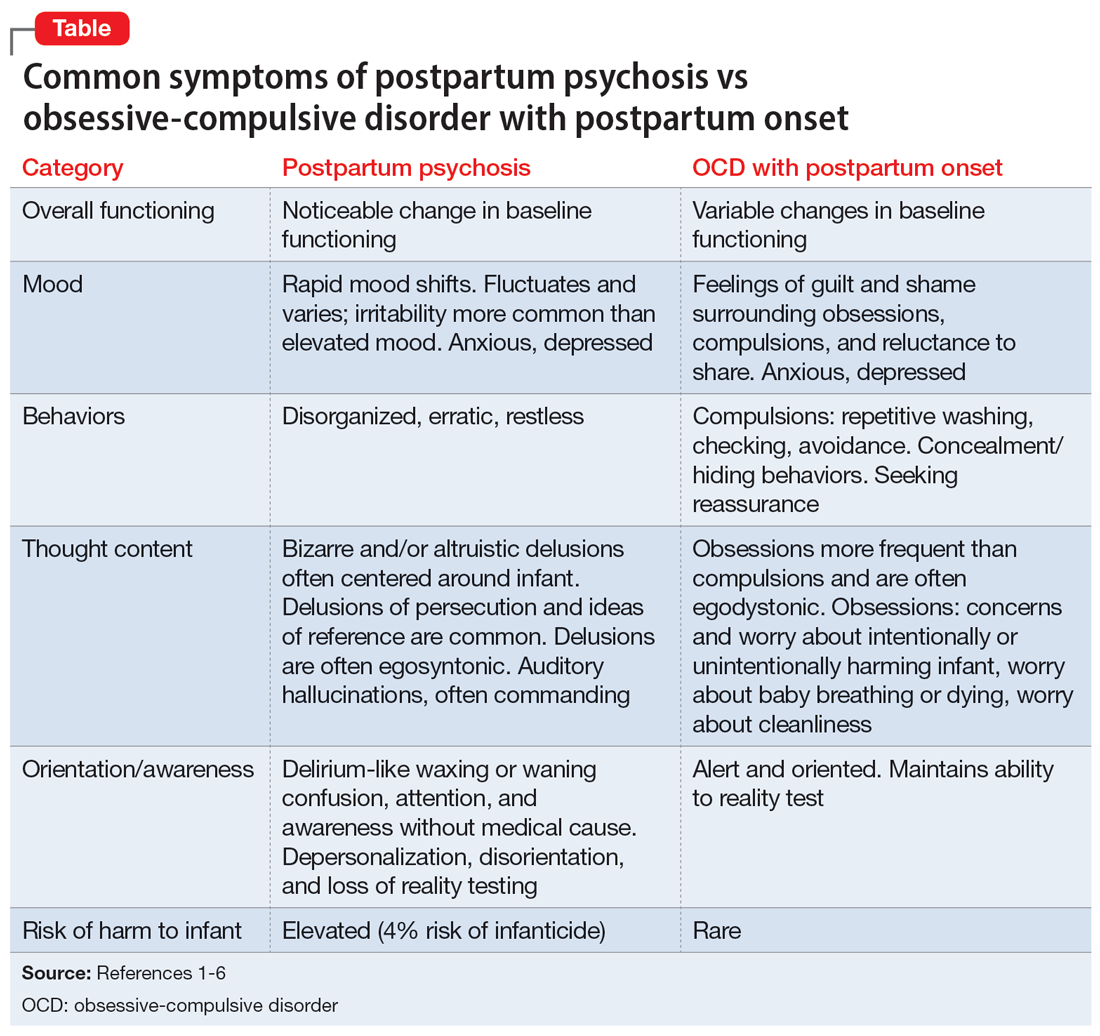

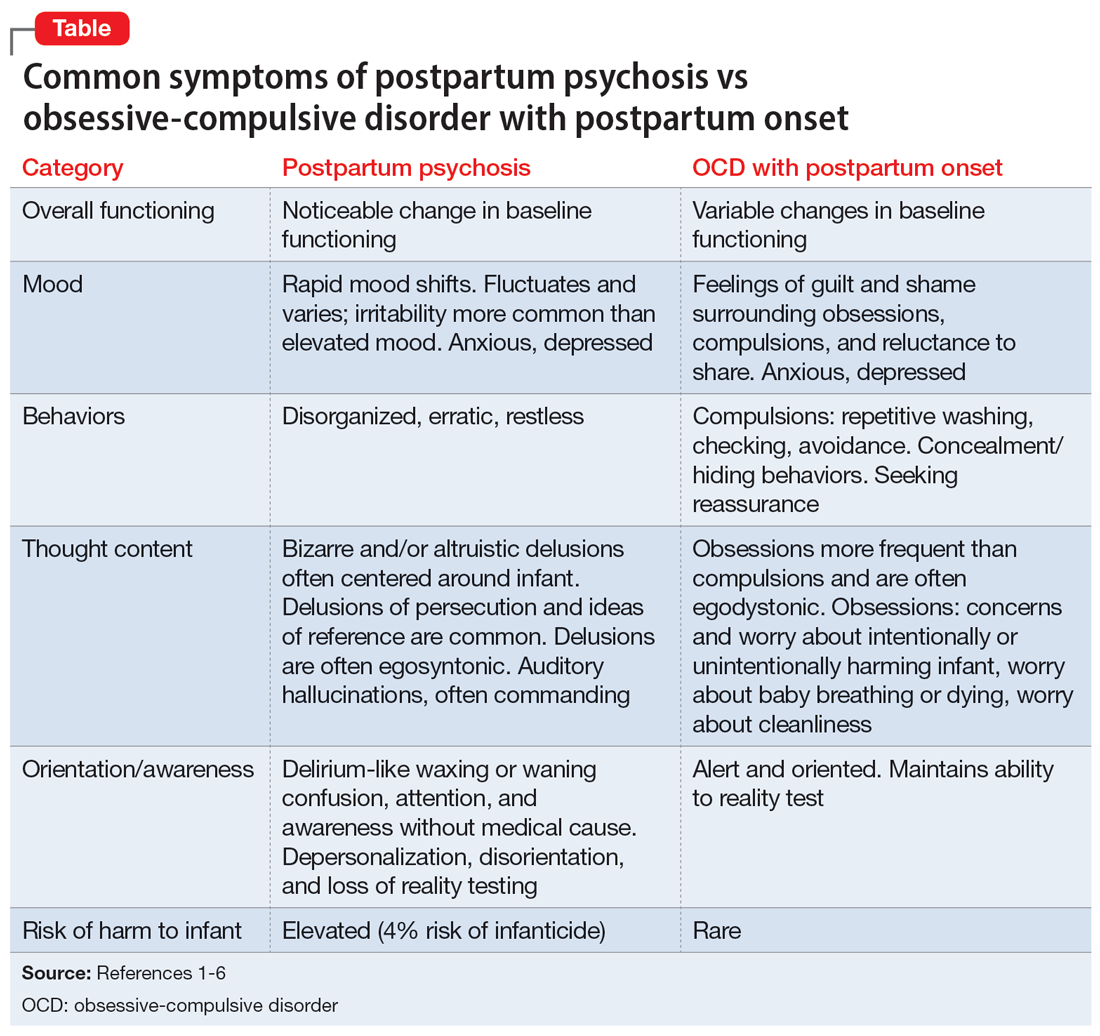

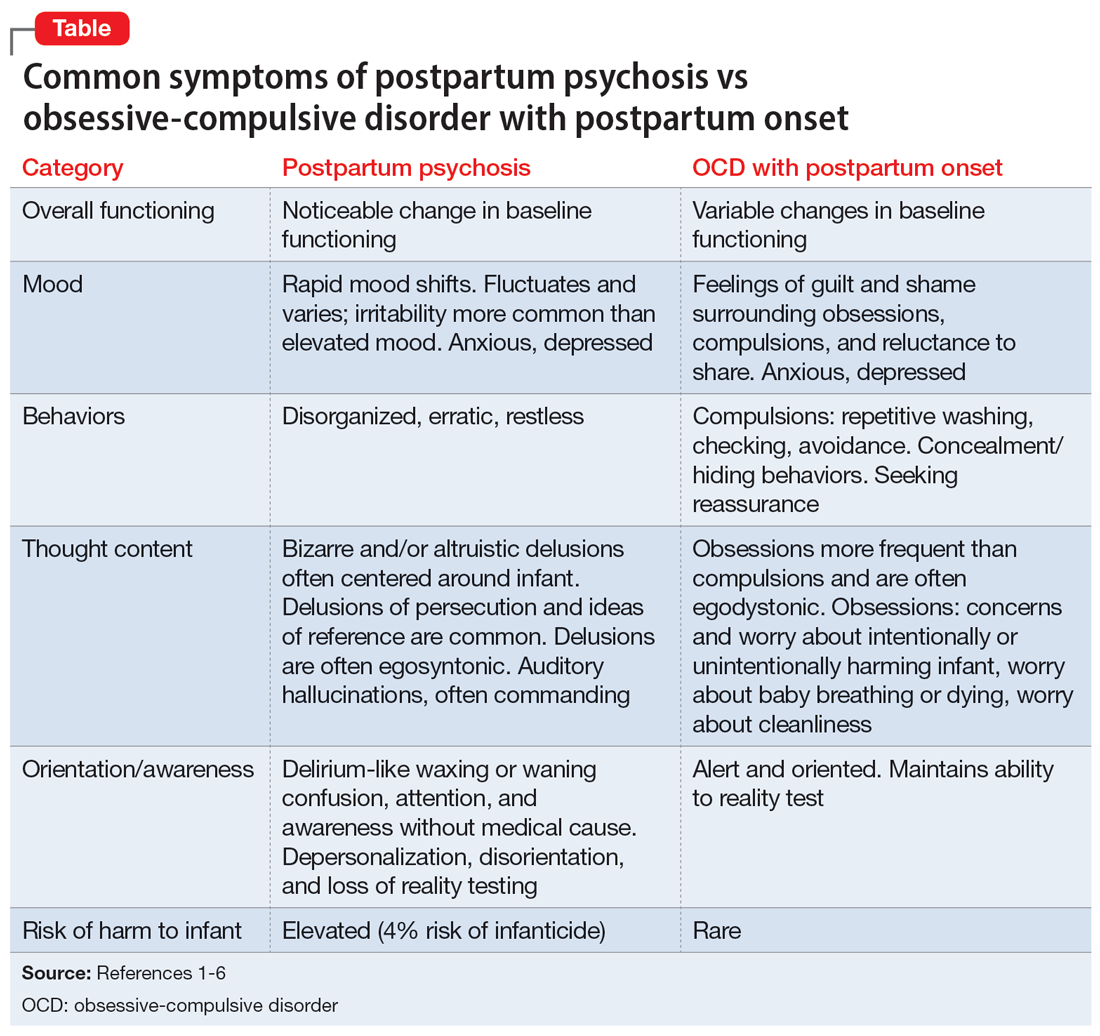

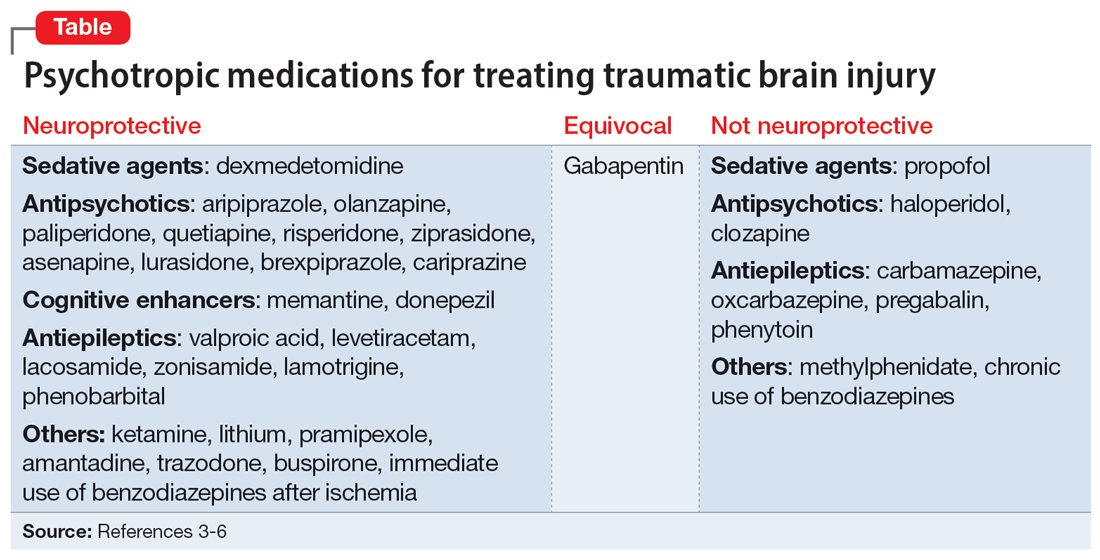

Ms. A’s initial presentation was concerning for a possible diagnosis of postpartum psychosis vs obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with postpartum onset; other differential diagnoses included MDD with peripartum onset and psychotic features (Table1-6). Ms. A’s subjective clinical history was significant for critical pertinent findings of both OCD with postpartum onset (ie, egodystonic intrusive thoughts, checking behaviors, feelings of shame, and seeking reassurance) and postpartum psychosis (ie, command auditory hallucinations and waxing/waning confusion), which added to diagnostic complexity.

Although postpartum psychosis is rare (1 to 2 cases per 1,000 women),5 it is considered a psychiatric emergency because it has significant potential for infanticide, morbidity, and mortality. Most symptoms develop within the first 2 weeks of the postpartum period.2 There are many risk factors for the development of postpartum psychosis; however, in first-time pregnancies, a previous diagnosis of BD I is the single most important risk factor.1 Approximately 20% to 30% of women with BD experience postpartum psychosis.4

For many patients (approximately 56.7%, according to 1 meta-analysis7), postpartum psychosis denotes an episode of BD, representing a more severe form of illness with increased risk of recurrence. Most manic or mixed mood episodes reoccur within the first year removed from the perinatal period. In contrast, for some patients (approximately 43.5% according to the same meta-analysis), the episode denotes “isolated postpartum psychosis.”7 Isolated postpartum psychosis is a psychotic episode that occurs only in the postpartum period with no recurrence of psychosis or recurrence of psychosis exclusive to postpartum periods. If treated, this type of postpartum psychosis has a more favorable prognosis than postpartum psychosis in a patient with BD.7 As such, a BD diagnosis should not be established at the onset of a patient’s first postpartum psychosis presentation. Regardless of type, all presentations of postpartum psychosis are considered a psychiatry emergency.

Continue to: The prevalence of OCD...

The prevalence of OCD with postpartum onset varies. One study estimated it occurs in 2.43% of cases.4 However, the true prevalence is likely underreported due to feelings of guilt or shame associated with intrusive thoughts, and fear of stigmatization and separation from the baby. Approximately 70.6% of women experiencing OCD with postpartum onset have a comorbid depressive disorder.4

Ms. A’s presentation to the psychiatric ED carried with it diagnostic complexity and uncertainty. Her initial presentation was concerning for elements of both postpartum psychosis and OCD with postpartum onset. After her evaluation in the psychiatric ED, there remained a lack of clear and convincing evidence for a diagnosis of OCD with postpartum onset, which eliminated the possibility of discharging Ms. A with robust safety planning and reinitiation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Additionally, because auditory hallucinations are atypical in OCD, the treatment team remained concerned for a diagnosis of postpartum psychosis, which would warrant hospitalization. With assistance from the institution’s reproductive psychiatrists, the treatment team discussed the importance of inpatient hospitalization for risk mitigation, close observation, and thorough evaluation for greater diagnostic clarity and certainty.

TREATMENT Involuntary hospitalization

The treatment team counsels Ms. A and her partner on her differential diagnoses, including the elevated acute risk of harm to herself and her baby if she has postpartum psychosis, as well as the need for continued observation and evaluation. When alone with a clinician, Ms. A says she understands and agrees to voluntary hospitalization. However, following a subsequent risk-benefit discussion with her partner, they both grew increasingly concerned about her separation from the baby and reinitiating her medications. Amid these concerns, the treatment team notices that Ms. A attempts to minimize her symptoms. Ms. A changes her mind and no longer consents to hospitalization. She is placed on a psychiatric hold for involuntary hospitalization on the psychiatric inpatient unit.

On the inpatient unit, the inpatient clinicians and a reproductive psychiatrist continue to evaluate Ms. A. Though her diagnosis remains unclear, Ms. A agrees to start a trial of quetiapine 100 mg/d titrated to 150 mg/d to manage her potential postpartum psychosis, depressed mood, insomnia (off-label), anxiety (off-label), and OCD (off-label). Lithium is deferred because Ms. A is breastfeeding.

[polldaddy:13041932]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

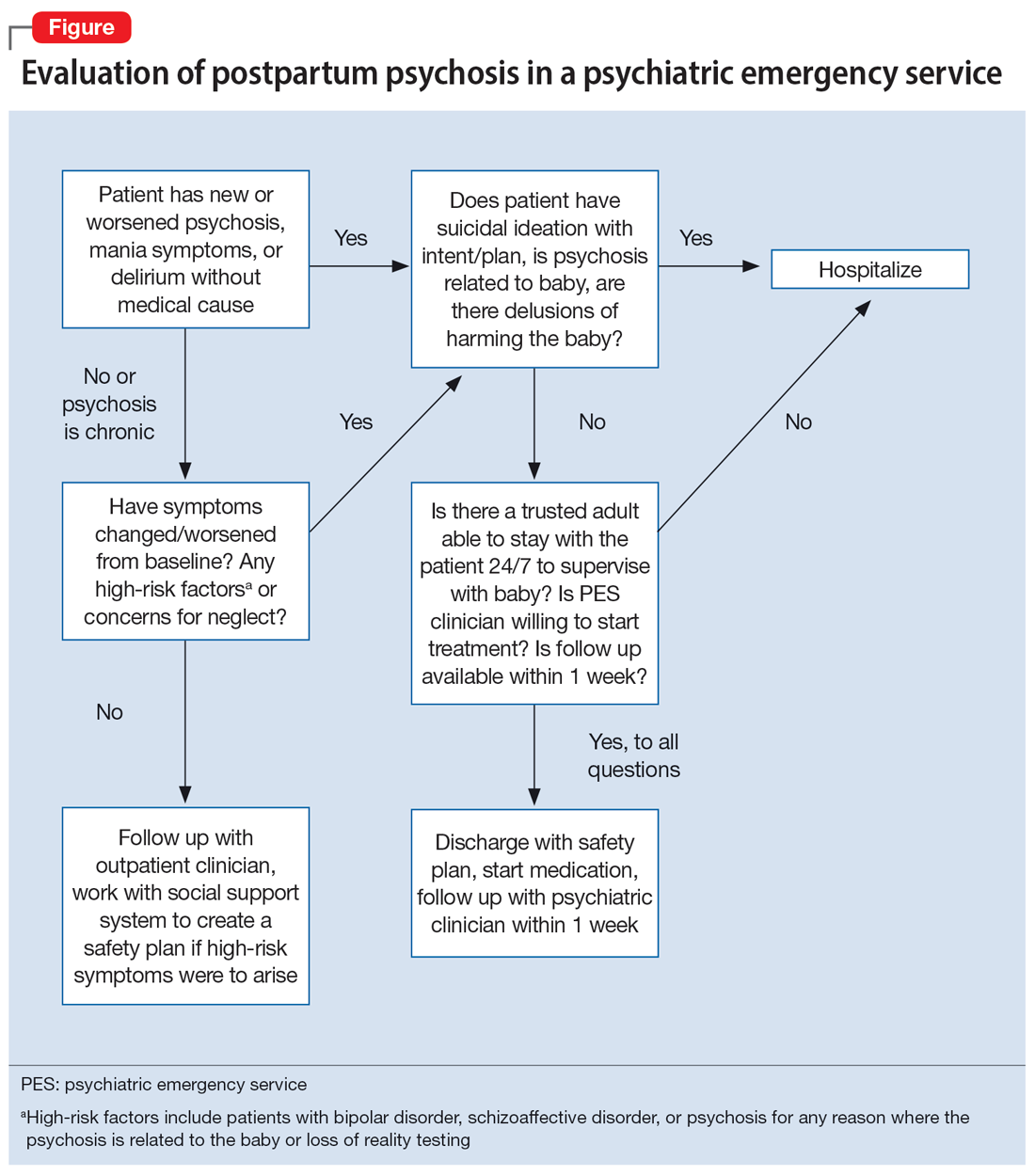

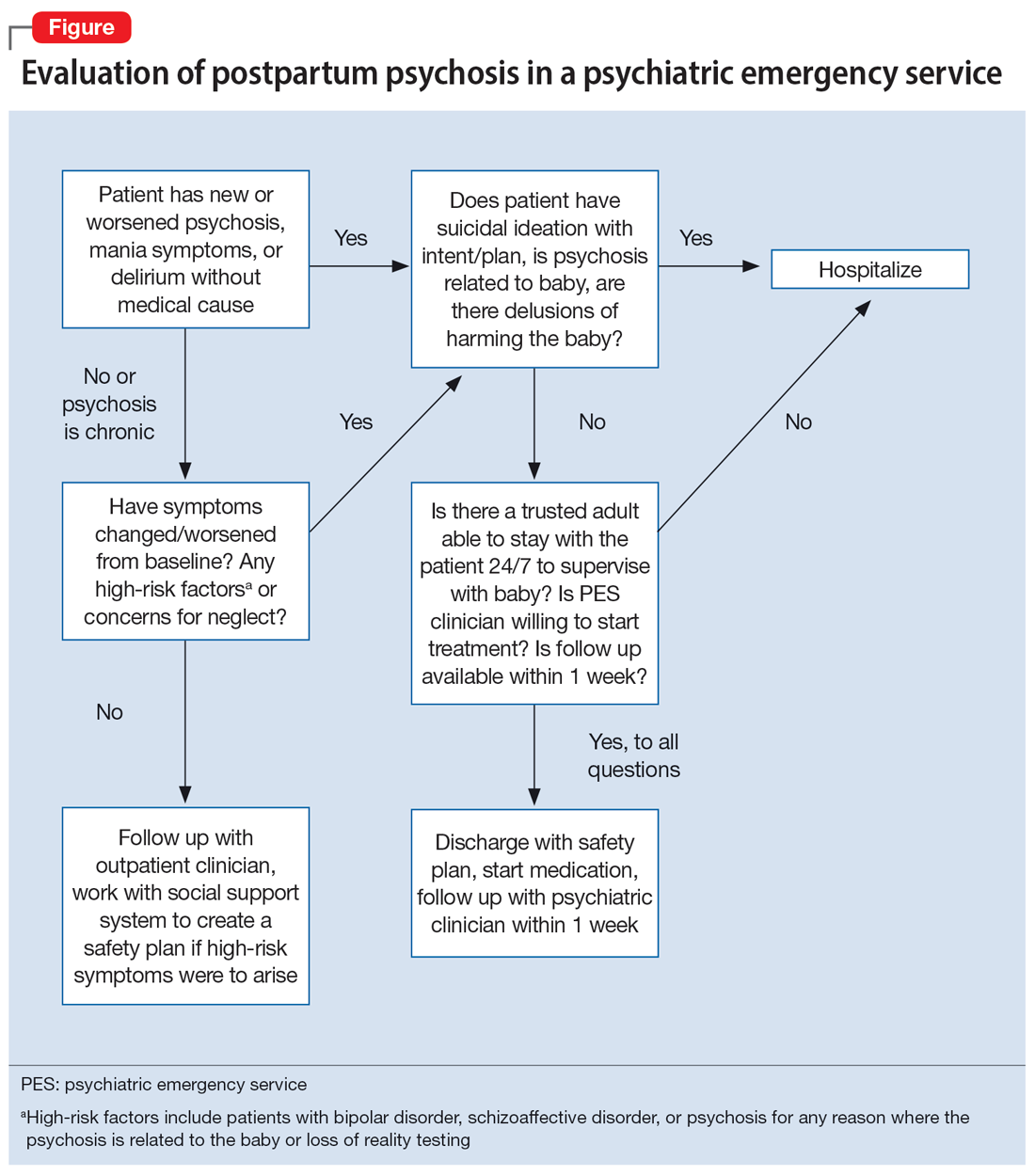

Due to an elevated acute risk of suicide and infanticide, postpartum psychosis represents a psychiatric emergency and often requires hospitalization. The Figure outlines steps in evaluating a patient with concerns for postpartum psychosis in a psychiatric emergency service setting. Due to the waxing and waning nature of symptoms, patients may appear psychiatrically stable at any time but remain at an overall elevated acute risk of harm to self and/or their baby.

If a patient is being considered for discharge based on yes answers to all questions in Step 2 of the Figure, the emergency psychiatric clinician must initiate appropriate psychotropic medications and complete robust safety planning with the patient and a trusted adult who will provide direct supervision. Safety planning may include (but is not limited to) strict return precautions, education on concerning symptoms and behaviors, psychotropic education and agreement of compliance, and detailed instructions on outpatient follow-up within 1 week. Ideally—and as was the case for Ms. A—a reproductive psychiatrist should be consulted in the emergency setting for shared decision-making on admission vs discharge, medication management, and outpatient follow-up considerations.

Because postpartum psychosis carries significant risks and hospitalization generally results in separating the patient from their baby, initiating psychotropics should not be delayed. Clinicians must consider the patient’s psychiatric history, allergies, and breastfeeding status.

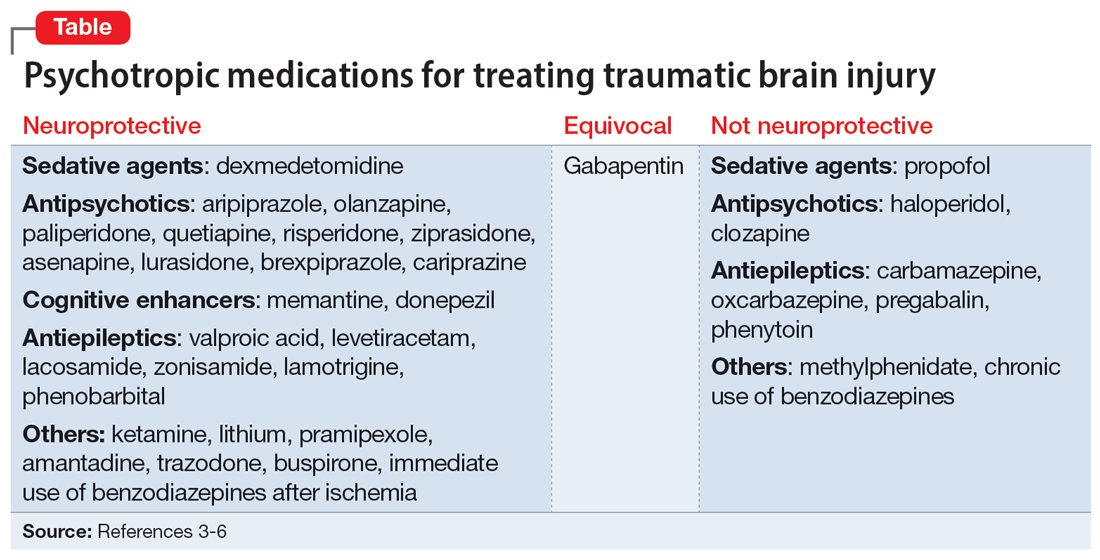

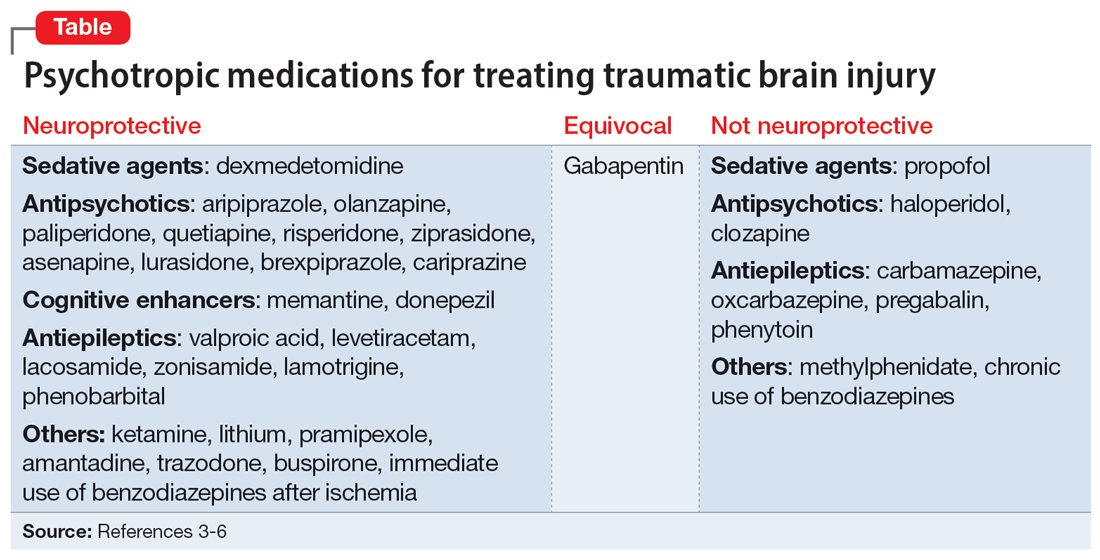

Based on current evidence, first-line treatment for postpartum psychosis includes a mood stabilizer, an antipsychotic, and possibly a benzodiazepine.6 Thus, an appropriate initial treatment regimen would be a benzodiazepine (particularly lorazepam due to its relatively shorter half-life) and an antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, olanzapine, or quetiapine) for acute psychosis, plus lithium for mood stabilization.1,5

If the postpartum psychosis represents an episode of BD, use of a long-term mood stabilizer may be required. In contrast, for isolated postpartum psychosis, clinicians may consider initiating psychotropics only in the immediate postpartum period, with an eventual slow taper. In future pregnancies, psychotropics may be reintroduced postpartum, which will avoid peripartum fetal exposure.8 If the patient is breastfeeding, lithium may be deferred in an acute care setting. For patients with evidence of catatonia, severe suicidality, refusal of oral intake with compromised nutrition, severe agitation, or treatment resistance, electroconvulsive therapy remains a safe and effective treatment option.6 Additionally, the safety of continued breastfeeding in acute psychosis must be considered, with the potential for recommending discontinuation, which would decrease sleep disruptions at night and increase the ability of others to feed the baby. Comprehensive care requires nonpharmacologic interventions, including psychoeducation for the patient and their family, individual psychotherapy, and expansion of psychosocial supports.

Continue to: Patients who have experienced...

Patients who have experienced an episode of postpartum psychosis are predisposed to another episode in future pregnancies.1 Current research recommends prophylaxis of recurrence with lithium monotherapy.1,2,5,6 Similar to other psychotropics in reproductive psychiatry, maintenance therapy on lithium requires a thorough “risk vs risk” discussion with the patient. The risk of lithium use while pregnant and/or breastfeeding must be weighed against the risks associated with postpartum psychosis (ie, infanticide, suicide, poor peripartum care, or poor infant bonding).

OUTCOME Improved mood

After 7 days of inpatient treatment with quetiapine, Ms. A demonstrates improvement in the targeted depressive symptoms (including improved motivation/energy and insomnia, decreased feelings of guilt, and denial of ongoing suicidal ideation). Additionally, the thoughts of harming her baby are less frequent, and command auditory hallucinations resolve. Upon discharge, Ms. A and her partner meet with inpatient clinicians for continued counseling, safety planning, and plans for outpatient follow-up with the institution’s reproductive psychiatrist.

The authors’ observations

Many aspects of Ms. A’s initial presentation in the psychiatric ED were challenging. Given the presence of symptoms of both psychosis and OCD, a diagnosis was difficult to ascertain in the emergency setting. Since command auditory hallucinations are atypical in patients with postpartum OCD, the treatment team maintained high suspicion for postpartum psychosis, which represented an emergency requiring inpatient care.

Hospitalization separated Ms. A from her baby, for whom she was the primary caregiver. Additional considerations for inpatient admission and psychotropic initiation were necessary, because Ms. A was breastfeeding. Although Ms. A’s partner was able to provide full-time childcare, the patient ultimately did not agree to hospitalization and required an emergency hold for involuntary admission, which was an additional barrier to care. Furthermore, her partner held unfavorable beliefs regarding psychotropic medications and Ms. A’s need for hospital admission, which required ongoing patient and partner education in the emergency, inpatient, and outpatient settings. Moreover, if Ms. A’s symptoms were ultimately attributable to postpartum OCD, the patient’s involuntary hospitalization might have increased the risk of stigmatization of mental illness and treatment with psychotropics.

Bottom Line

The peripartum period is a vulnerable time for patients, particularly those with previously diagnosed psychiatric illnesses. Postpartum psychosis is the most severe form of postpartum psychiatric illness and often represents an episode of bipolar disorder. Due to an elevated acute risk of suicide and infanticide, postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and warrants inpatient hospitalization for immediate intervention.

Related Resources

- Sharma V. Does your patient have postpartum OCD? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(5):9-10.

- Hatters Friedman S, Prakash C, Nagel-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Prazosin • Minipress

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

1. Raza SK, Raza S. Postpartum Psychosis. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544304/

2. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. What Is Postpartum Psychosis: This Is What You Need to Know. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Published November 15, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://womensmentalhealth.org/posts/postpartum-psychosis-ten-things-need-know-2/

3. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://womensmentalhealth.org/specialty-clinics-2/postpartum-psychiatric-disorders-2/

4. Sharma V, Sommerdyk C. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the postpartum period: diagnosis, differential diagnosis and management. Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11(4):543-552. doi:10.2217/whe.15.20

5. Osborne LM. Recognizing and managing postpartum psychosis: a clinical guide for obstetric providers. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(3):455-468. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2018.04.005

6. Hutner LA, Catapano LA, Nagle-Yang SM, et al, eds. Textbook of Women’s Reproductive Mental Health. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

7. Gilden J, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Long-term outcomes of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19r12906. doi:10.4088/JCP.19r12906

8. Bergink V, Boyce P, Munk-Olsen T. Postpartum psychosis: a valuable misnomer. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(2):102-103. doi:10.1177/0004867414564698

CASE Thoughts of harming baby

Ms. A, age 37, is G4P2, 4 months postpartum, and breastfeeding. She has major depressive disorder (MDD) with peripartum onset, posttraumatic stress disorder, and mild intellectual disability. For years she has been stable on fluoxetine 40 mg/d and prazosin 2 mg/d. Despite recent titration of her medications, at her most recent outpatient appointment Ms. A reports having a depressed mood with frequent crying, insomnia, a lack of desire to bond with her baby, and feelings of shame. She also says she has had auditory hallucinations and thoughts of harming her baby. Ms. A’s outpatient physician makes an urgent request for her to be evaluated at the psychiatric emergency department (ED).

HISTORY Depression and possible auditory hallucinations

Ms. A developed MDD following the birth of her first child, for which her care team initiated fluoxetine at 20 mg/d and titrated it to 40 mg/d,which was effective. At that time, her outpatient physician documented potential psychotic features, including vague descriptions of derogatory auditory hallucinations. However, it was unclear if these auditory hallucinations were more representative of a distressing inner monologue without the quality of an external voice. The team determined that Ms. A was not at acute risk for harm to herself or her baby and was appropriate for outpatient care. Because the nature of these possible auditory hallucinations was mild, nondistressing, and nonthreatening, the treatment team did not initiate an antipsychotic and Ms. A was not hospitalized. She has no history of hypomanic/manic episodes and has never met criteria for a psychotic disorder.

EVALUATION Distressing thoughts and discontinued medications

During the evaluation by psychiatric emergency services, Ms. A reports that 2 weeks after giving birth she experienced a worsening of her depressive symptoms. She says she began hearing voices telling her to harm herself and her baby and describes frequent distressing thoughts, such as stabbing her baby with a knife and running over her baby with a car. Ms. A says she repeatedly wakes up at night to check on her baby’s breathing, overfeeds her baby due to a fear of inadequate nutrition, and notes intermittent feelings of confusion. Afraid of being alone with her infant, Ms. A asks her partner and mother to move in with her. Additionally, she says 2 weeks ago she discontinued all her medications at the suggestion of her partner, who recommended herbal supplements. Ms. A’s initial routine laboratory results are unremarkable and her urine drug screen is negative for all substances.

[polldaddy:13041928]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 85% of birthing parents experience some form of postpartum mood disturbance; 10% to 15% develop more significant symptoms of anxiety or depression.3 The etiology of postpartum illness is multifactorial, and includes psychiatric personal/family history, insomnia, acute and chronic psychosocial stressors, and rapid hormone fluctuations.1 As a result, the postpartum period represents a vulnerable time for birthing parents, particularly those with previously established psychiatric illness.

Ms. A’s initial presentation was concerning for a possible diagnosis of postpartum psychosis vs obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with postpartum onset; other differential diagnoses included MDD with peripartum onset and psychotic features (Table1-6). Ms. A’s subjective clinical history was significant for critical pertinent findings of both OCD with postpartum onset (ie, egodystonic intrusive thoughts, checking behaviors, feelings of shame, and seeking reassurance) and postpartum psychosis (ie, command auditory hallucinations and waxing/waning confusion), which added to diagnostic complexity.

Although postpartum psychosis is rare (1 to 2 cases per 1,000 women),5 it is considered a psychiatric emergency because it has significant potential for infanticide, morbidity, and mortality. Most symptoms develop within the first 2 weeks of the postpartum period.2 There are many risk factors for the development of postpartum psychosis; however, in first-time pregnancies, a previous diagnosis of BD I is the single most important risk factor.1 Approximately 20% to 30% of women with BD experience postpartum psychosis.4

For many patients (approximately 56.7%, according to 1 meta-analysis7), postpartum psychosis denotes an episode of BD, representing a more severe form of illness with increased risk of recurrence. Most manic or mixed mood episodes reoccur within the first year removed from the perinatal period. In contrast, for some patients (approximately 43.5% according to the same meta-analysis), the episode denotes “isolated postpartum psychosis.”7 Isolated postpartum psychosis is a psychotic episode that occurs only in the postpartum period with no recurrence of psychosis or recurrence of psychosis exclusive to postpartum periods. If treated, this type of postpartum psychosis has a more favorable prognosis than postpartum psychosis in a patient with BD.7 As such, a BD diagnosis should not be established at the onset of a patient’s first postpartum psychosis presentation. Regardless of type, all presentations of postpartum psychosis are considered a psychiatry emergency.

Continue to: The prevalence of OCD...

The prevalence of OCD with postpartum onset varies. One study estimated it occurs in 2.43% of cases.4 However, the true prevalence is likely underreported due to feelings of guilt or shame associated with intrusive thoughts, and fear of stigmatization and separation from the baby. Approximately 70.6% of women experiencing OCD with postpartum onset have a comorbid depressive disorder.4

Ms. A’s presentation to the psychiatric ED carried with it diagnostic complexity and uncertainty. Her initial presentation was concerning for elements of both postpartum psychosis and OCD with postpartum onset. After her evaluation in the psychiatric ED, there remained a lack of clear and convincing evidence for a diagnosis of OCD with postpartum onset, which eliminated the possibility of discharging Ms. A with robust safety planning and reinitiation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Additionally, because auditory hallucinations are atypical in OCD, the treatment team remained concerned for a diagnosis of postpartum psychosis, which would warrant hospitalization. With assistance from the institution’s reproductive psychiatrists, the treatment team discussed the importance of inpatient hospitalization for risk mitigation, close observation, and thorough evaluation for greater diagnostic clarity and certainty.

TREATMENT Involuntary hospitalization

The treatment team counsels Ms. A and her partner on her differential diagnoses, including the elevated acute risk of harm to herself and her baby if she has postpartum psychosis, as well as the need for continued observation and evaluation. When alone with a clinician, Ms. A says she understands and agrees to voluntary hospitalization. However, following a subsequent risk-benefit discussion with her partner, they both grew increasingly concerned about her separation from the baby and reinitiating her medications. Amid these concerns, the treatment team notices that Ms. A attempts to minimize her symptoms. Ms. A changes her mind and no longer consents to hospitalization. She is placed on a psychiatric hold for involuntary hospitalization on the psychiatric inpatient unit.

On the inpatient unit, the inpatient clinicians and a reproductive psychiatrist continue to evaluate Ms. A. Though her diagnosis remains unclear, Ms. A agrees to start a trial of quetiapine 100 mg/d titrated to 150 mg/d to manage her potential postpartum psychosis, depressed mood, insomnia (off-label), anxiety (off-label), and OCD (off-label). Lithium is deferred because Ms. A is breastfeeding.

[polldaddy:13041932]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

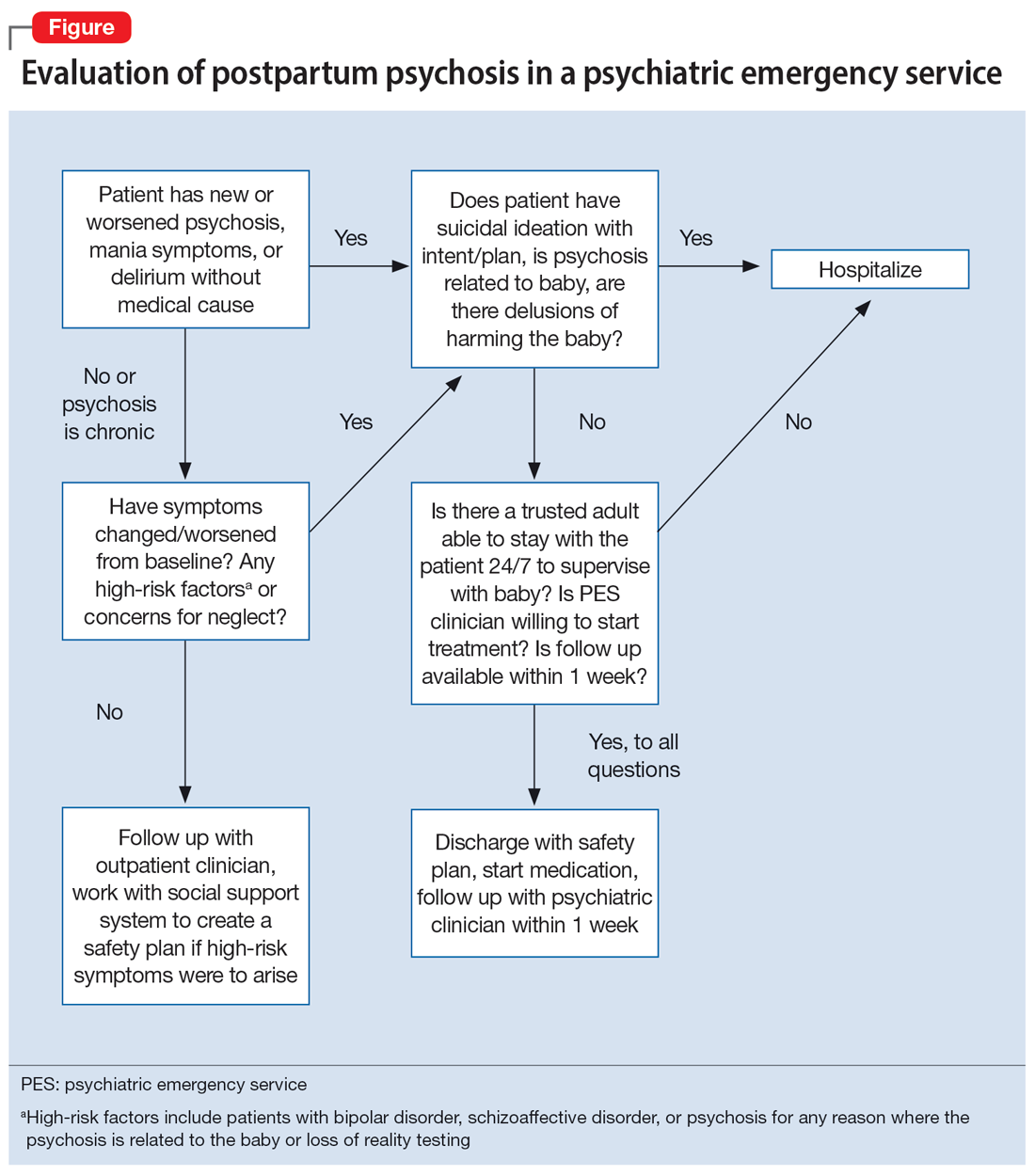

Due to an elevated acute risk of suicide and infanticide, postpartum psychosis represents a psychiatric emergency and often requires hospitalization. The Figure outlines steps in evaluating a patient with concerns for postpartum psychosis in a psychiatric emergency service setting. Due to the waxing and waning nature of symptoms, patients may appear psychiatrically stable at any time but remain at an overall elevated acute risk of harm to self and/or their baby.

If a patient is being considered for discharge based on yes answers to all questions in Step 2 of the Figure, the emergency psychiatric clinician must initiate appropriate psychotropic medications and complete robust safety planning with the patient and a trusted adult who will provide direct supervision. Safety planning may include (but is not limited to) strict return precautions, education on concerning symptoms and behaviors, psychotropic education and agreement of compliance, and detailed instructions on outpatient follow-up within 1 week. Ideally—and as was the case for Ms. A—a reproductive psychiatrist should be consulted in the emergency setting for shared decision-making on admission vs discharge, medication management, and outpatient follow-up considerations.

Because postpartum psychosis carries significant risks and hospitalization generally results in separating the patient from their baby, initiating psychotropics should not be delayed. Clinicians must consider the patient’s psychiatric history, allergies, and breastfeeding status.

Based on current evidence, first-line treatment for postpartum psychosis includes a mood stabilizer, an antipsychotic, and possibly a benzodiazepine.6 Thus, an appropriate initial treatment regimen would be a benzodiazepine (particularly lorazepam due to its relatively shorter half-life) and an antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, olanzapine, or quetiapine) for acute psychosis, plus lithium for mood stabilization.1,5

If the postpartum psychosis represents an episode of BD, use of a long-term mood stabilizer may be required. In contrast, for isolated postpartum psychosis, clinicians may consider initiating psychotropics only in the immediate postpartum period, with an eventual slow taper. In future pregnancies, psychotropics may be reintroduced postpartum, which will avoid peripartum fetal exposure.8 If the patient is breastfeeding, lithium may be deferred in an acute care setting. For patients with evidence of catatonia, severe suicidality, refusal of oral intake with compromised nutrition, severe agitation, or treatment resistance, electroconvulsive therapy remains a safe and effective treatment option.6 Additionally, the safety of continued breastfeeding in acute psychosis must be considered, with the potential for recommending discontinuation, which would decrease sleep disruptions at night and increase the ability of others to feed the baby. Comprehensive care requires nonpharmacologic interventions, including psychoeducation for the patient and their family, individual psychotherapy, and expansion of psychosocial supports.

Continue to: Patients who have experienced...

Patients who have experienced an episode of postpartum psychosis are predisposed to another episode in future pregnancies.1 Current research recommends prophylaxis of recurrence with lithium monotherapy.1,2,5,6 Similar to other psychotropics in reproductive psychiatry, maintenance therapy on lithium requires a thorough “risk vs risk” discussion with the patient. The risk of lithium use while pregnant and/or breastfeeding must be weighed against the risks associated with postpartum psychosis (ie, infanticide, suicide, poor peripartum care, or poor infant bonding).

OUTCOME Improved mood

After 7 days of inpatient treatment with quetiapine, Ms. A demonstrates improvement in the targeted depressive symptoms (including improved motivation/energy and insomnia, decreased feelings of guilt, and denial of ongoing suicidal ideation). Additionally, the thoughts of harming her baby are less frequent, and command auditory hallucinations resolve. Upon discharge, Ms. A and her partner meet with inpatient clinicians for continued counseling, safety planning, and plans for outpatient follow-up with the institution’s reproductive psychiatrist.

The authors’ observations

Many aspects of Ms. A’s initial presentation in the psychiatric ED were challenging. Given the presence of symptoms of both psychosis and OCD, a diagnosis was difficult to ascertain in the emergency setting. Since command auditory hallucinations are atypical in patients with postpartum OCD, the treatment team maintained high suspicion for postpartum psychosis, which represented an emergency requiring inpatient care.

Hospitalization separated Ms. A from her baby, for whom she was the primary caregiver. Additional considerations for inpatient admission and psychotropic initiation were necessary, because Ms. A was breastfeeding. Although Ms. A’s partner was able to provide full-time childcare, the patient ultimately did not agree to hospitalization and required an emergency hold for involuntary admission, which was an additional barrier to care. Furthermore, her partner held unfavorable beliefs regarding psychotropic medications and Ms. A’s need for hospital admission, which required ongoing patient and partner education in the emergency, inpatient, and outpatient settings. Moreover, if Ms. A’s symptoms were ultimately attributable to postpartum OCD, the patient’s involuntary hospitalization might have increased the risk of stigmatization of mental illness and treatment with psychotropics.

Bottom Line

The peripartum period is a vulnerable time for patients, particularly those with previously diagnosed psychiatric illnesses. Postpartum psychosis is the most severe form of postpartum psychiatric illness and often represents an episode of bipolar disorder. Due to an elevated acute risk of suicide and infanticide, postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and warrants inpatient hospitalization for immediate intervention.

Related Resources

- Sharma V. Does your patient have postpartum OCD? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(5):9-10.

- Hatters Friedman S, Prakash C, Nagel-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Prazosin • Minipress

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

CASE Thoughts of harming baby

Ms. A, age 37, is G4P2, 4 months postpartum, and breastfeeding. She has major depressive disorder (MDD) with peripartum onset, posttraumatic stress disorder, and mild intellectual disability. For years she has been stable on fluoxetine 40 mg/d and prazosin 2 mg/d. Despite recent titration of her medications, at her most recent outpatient appointment Ms. A reports having a depressed mood with frequent crying, insomnia, a lack of desire to bond with her baby, and feelings of shame. She also says she has had auditory hallucinations and thoughts of harming her baby. Ms. A’s outpatient physician makes an urgent request for her to be evaluated at the psychiatric emergency department (ED).

HISTORY Depression and possible auditory hallucinations

Ms. A developed MDD following the birth of her first child, for which her care team initiated fluoxetine at 20 mg/d and titrated it to 40 mg/d,which was effective. At that time, her outpatient physician documented potential psychotic features, including vague descriptions of derogatory auditory hallucinations. However, it was unclear if these auditory hallucinations were more representative of a distressing inner monologue without the quality of an external voice. The team determined that Ms. A was not at acute risk for harm to herself or her baby and was appropriate for outpatient care. Because the nature of these possible auditory hallucinations was mild, nondistressing, and nonthreatening, the treatment team did not initiate an antipsychotic and Ms. A was not hospitalized. She has no history of hypomanic/manic episodes and has never met criteria for a psychotic disorder.

EVALUATION Distressing thoughts and discontinued medications

During the evaluation by psychiatric emergency services, Ms. A reports that 2 weeks after giving birth she experienced a worsening of her depressive symptoms. She says she began hearing voices telling her to harm herself and her baby and describes frequent distressing thoughts, such as stabbing her baby with a knife and running over her baby with a car. Ms. A says she repeatedly wakes up at night to check on her baby’s breathing, overfeeds her baby due to a fear of inadequate nutrition, and notes intermittent feelings of confusion. Afraid of being alone with her infant, Ms. A asks her partner and mother to move in with her. Additionally, she says 2 weeks ago she discontinued all her medications at the suggestion of her partner, who recommended herbal supplements. Ms. A’s initial routine laboratory results are unremarkable and her urine drug screen is negative for all substances.

[polldaddy:13041928]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 85% of birthing parents experience some form of postpartum mood disturbance; 10% to 15% develop more significant symptoms of anxiety or depression.3 The etiology of postpartum illness is multifactorial, and includes psychiatric personal/family history, insomnia, acute and chronic psychosocial stressors, and rapid hormone fluctuations.1 As a result, the postpartum period represents a vulnerable time for birthing parents, particularly those with previously established psychiatric illness.

Ms. A’s initial presentation was concerning for a possible diagnosis of postpartum psychosis vs obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with postpartum onset; other differential diagnoses included MDD with peripartum onset and psychotic features (Table1-6). Ms. A’s subjective clinical history was significant for critical pertinent findings of both OCD with postpartum onset (ie, egodystonic intrusive thoughts, checking behaviors, feelings of shame, and seeking reassurance) and postpartum psychosis (ie, command auditory hallucinations and waxing/waning confusion), which added to diagnostic complexity.

Although postpartum psychosis is rare (1 to 2 cases per 1,000 women),5 it is considered a psychiatric emergency because it has significant potential for infanticide, morbidity, and mortality. Most symptoms develop within the first 2 weeks of the postpartum period.2 There are many risk factors for the development of postpartum psychosis; however, in first-time pregnancies, a previous diagnosis of BD I is the single most important risk factor.1 Approximately 20% to 30% of women with BD experience postpartum psychosis.4

For many patients (approximately 56.7%, according to 1 meta-analysis7), postpartum psychosis denotes an episode of BD, representing a more severe form of illness with increased risk of recurrence. Most manic or mixed mood episodes reoccur within the first year removed from the perinatal period. In contrast, for some patients (approximately 43.5% according to the same meta-analysis), the episode denotes “isolated postpartum psychosis.”7 Isolated postpartum psychosis is a psychotic episode that occurs only in the postpartum period with no recurrence of psychosis or recurrence of psychosis exclusive to postpartum periods. If treated, this type of postpartum psychosis has a more favorable prognosis than postpartum psychosis in a patient with BD.7 As such, a BD diagnosis should not be established at the onset of a patient’s first postpartum psychosis presentation. Regardless of type, all presentations of postpartum psychosis are considered a psychiatry emergency.

Continue to: The prevalence of OCD...

The prevalence of OCD with postpartum onset varies. One study estimated it occurs in 2.43% of cases.4 However, the true prevalence is likely underreported due to feelings of guilt or shame associated with intrusive thoughts, and fear of stigmatization and separation from the baby. Approximately 70.6% of women experiencing OCD with postpartum onset have a comorbid depressive disorder.4

Ms. A’s presentation to the psychiatric ED carried with it diagnostic complexity and uncertainty. Her initial presentation was concerning for elements of both postpartum psychosis and OCD with postpartum onset. After her evaluation in the psychiatric ED, there remained a lack of clear and convincing evidence for a diagnosis of OCD with postpartum onset, which eliminated the possibility of discharging Ms. A with robust safety planning and reinitiation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Additionally, because auditory hallucinations are atypical in OCD, the treatment team remained concerned for a diagnosis of postpartum psychosis, which would warrant hospitalization. With assistance from the institution’s reproductive psychiatrists, the treatment team discussed the importance of inpatient hospitalization for risk mitigation, close observation, and thorough evaluation for greater diagnostic clarity and certainty.

TREATMENT Involuntary hospitalization

The treatment team counsels Ms. A and her partner on her differential diagnoses, including the elevated acute risk of harm to herself and her baby if she has postpartum psychosis, as well as the need for continued observation and evaluation. When alone with a clinician, Ms. A says she understands and agrees to voluntary hospitalization. However, following a subsequent risk-benefit discussion with her partner, they both grew increasingly concerned about her separation from the baby and reinitiating her medications. Amid these concerns, the treatment team notices that Ms. A attempts to minimize her symptoms. Ms. A changes her mind and no longer consents to hospitalization. She is placed on a psychiatric hold for involuntary hospitalization on the psychiatric inpatient unit.

On the inpatient unit, the inpatient clinicians and a reproductive psychiatrist continue to evaluate Ms. A. Though her diagnosis remains unclear, Ms. A agrees to start a trial of quetiapine 100 mg/d titrated to 150 mg/d to manage her potential postpartum psychosis, depressed mood, insomnia (off-label), anxiety (off-label), and OCD (off-label). Lithium is deferred because Ms. A is breastfeeding.

[polldaddy:13041932]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Due to an elevated acute risk of suicide and infanticide, postpartum psychosis represents a psychiatric emergency and often requires hospitalization. The Figure outlines steps in evaluating a patient with concerns for postpartum psychosis in a psychiatric emergency service setting. Due to the waxing and waning nature of symptoms, patients may appear psychiatrically stable at any time but remain at an overall elevated acute risk of harm to self and/or their baby.

If a patient is being considered for discharge based on yes answers to all questions in Step 2 of the Figure, the emergency psychiatric clinician must initiate appropriate psychotropic medications and complete robust safety planning with the patient and a trusted adult who will provide direct supervision. Safety planning may include (but is not limited to) strict return precautions, education on concerning symptoms and behaviors, psychotropic education and agreement of compliance, and detailed instructions on outpatient follow-up within 1 week. Ideally—and as was the case for Ms. A—a reproductive psychiatrist should be consulted in the emergency setting for shared decision-making on admission vs discharge, medication management, and outpatient follow-up considerations.

Because postpartum psychosis carries significant risks and hospitalization generally results in separating the patient from their baby, initiating psychotropics should not be delayed. Clinicians must consider the patient’s psychiatric history, allergies, and breastfeeding status.

Based on current evidence, first-line treatment for postpartum psychosis includes a mood stabilizer, an antipsychotic, and possibly a benzodiazepine.6 Thus, an appropriate initial treatment regimen would be a benzodiazepine (particularly lorazepam due to its relatively shorter half-life) and an antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, olanzapine, or quetiapine) for acute psychosis, plus lithium for mood stabilization.1,5

If the postpartum psychosis represents an episode of BD, use of a long-term mood stabilizer may be required. In contrast, for isolated postpartum psychosis, clinicians may consider initiating psychotropics only in the immediate postpartum period, with an eventual slow taper. In future pregnancies, psychotropics may be reintroduced postpartum, which will avoid peripartum fetal exposure.8 If the patient is breastfeeding, lithium may be deferred in an acute care setting. For patients with evidence of catatonia, severe suicidality, refusal of oral intake with compromised nutrition, severe agitation, or treatment resistance, electroconvulsive therapy remains a safe and effective treatment option.6 Additionally, the safety of continued breastfeeding in acute psychosis must be considered, with the potential for recommending discontinuation, which would decrease sleep disruptions at night and increase the ability of others to feed the baby. Comprehensive care requires nonpharmacologic interventions, including psychoeducation for the patient and their family, individual psychotherapy, and expansion of psychosocial supports.

Continue to: Patients who have experienced...

Patients who have experienced an episode of postpartum psychosis are predisposed to another episode in future pregnancies.1 Current research recommends prophylaxis of recurrence with lithium monotherapy.1,2,5,6 Similar to other psychotropics in reproductive psychiatry, maintenance therapy on lithium requires a thorough “risk vs risk” discussion with the patient. The risk of lithium use while pregnant and/or breastfeeding must be weighed against the risks associated with postpartum psychosis (ie, infanticide, suicide, poor peripartum care, or poor infant bonding).

OUTCOME Improved mood

After 7 days of inpatient treatment with quetiapine, Ms. A demonstrates improvement in the targeted depressive symptoms (including improved motivation/energy and insomnia, decreased feelings of guilt, and denial of ongoing suicidal ideation). Additionally, the thoughts of harming her baby are less frequent, and command auditory hallucinations resolve. Upon discharge, Ms. A and her partner meet with inpatient clinicians for continued counseling, safety planning, and plans for outpatient follow-up with the institution’s reproductive psychiatrist.

The authors’ observations

Many aspects of Ms. A’s initial presentation in the psychiatric ED were challenging. Given the presence of symptoms of both psychosis and OCD, a diagnosis was difficult to ascertain in the emergency setting. Since command auditory hallucinations are atypical in patients with postpartum OCD, the treatment team maintained high suspicion for postpartum psychosis, which represented an emergency requiring inpatient care.

Hospitalization separated Ms. A from her baby, for whom she was the primary caregiver. Additional considerations for inpatient admission and psychotropic initiation were necessary, because Ms. A was breastfeeding. Although Ms. A’s partner was able to provide full-time childcare, the patient ultimately did not agree to hospitalization and required an emergency hold for involuntary admission, which was an additional barrier to care. Furthermore, her partner held unfavorable beliefs regarding psychotropic medications and Ms. A’s need for hospital admission, which required ongoing patient and partner education in the emergency, inpatient, and outpatient settings. Moreover, if Ms. A’s symptoms were ultimately attributable to postpartum OCD, the patient’s involuntary hospitalization might have increased the risk of stigmatization of mental illness and treatment with psychotropics.

Bottom Line

The peripartum period is a vulnerable time for patients, particularly those with previously diagnosed psychiatric illnesses. Postpartum psychosis is the most severe form of postpartum psychiatric illness and often represents an episode of bipolar disorder. Due to an elevated acute risk of suicide and infanticide, postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency and warrants inpatient hospitalization for immediate intervention.

Related Resources

- Sharma V. Does your patient have postpartum OCD? Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(5):9-10.

- Hatters Friedman S, Prakash C, Nagel-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Prazosin • Minipress

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakene

1. Raza SK, Raza S. Postpartum Psychosis. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544304/

2. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. What Is Postpartum Psychosis: This Is What You Need to Know. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Published November 15, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://womensmentalhealth.org/posts/postpartum-psychosis-ten-things-need-know-2/

3. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://womensmentalhealth.org/specialty-clinics-2/postpartum-psychiatric-disorders-2/

4. Sharma V, Sommerdyk C. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the postpartum period: diagnosis, differential diagnosis and management. Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11(4):543-552. doi:10.2217/whe.15.20

5. Osborne LM. Recognizing and managing postpartum psychosis: a clinical guide for obstetric providers. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(3):455-468. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2018.04.005

6. Hutner LA, Catapano LA, Nagle-Yang SM, et al, eds. Textbook of Women’s Reproductive Mental Health. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

7. Gilden J, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Long-term outcomes of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19r12906. doi:10.4088/JCP.19r12906

8. Bergink V, Boyce P, Munk-Olsen T. Postpartum psychosis: a valuable misnomer. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(2):102-103. doi:10.1177/0004867414564698

1. Raza SK, Raza S. Postpartum Psychosis. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544304/

2. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. What Is Postpartum Psychosis: This Is What You Need to Know. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Published November 15, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://womensmentalhealth.org/posts/postpartum-psychosis-ten-things-need-know-2/

3. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders. MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://womensmentalhealth.org/specialty-clinics-2/postpartum-psychiatric-disorders-2/

4. Sharma V, Sommerdyk C. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the postpartum period: diagnosis, differential diagnosis and management. Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11(4):543-552. doi:10.2217/whe.15.20

5. Osborne LM. Recognizing and managing postpartum psychosis: a clinical guide for obstetric providers. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(3):455-468. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2018.04.005

6. Hutner LA, Catapano LA, Nagle-Yang SM, et al, eds. Textbook of Women’s Reproductive Mental Health. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

7. Gilden J, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Long-term outcomes of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19r12906. doi:10.4088/JCP.19r12906

8. Bergink V, Boyce P, Munk-Olsen T. Postpartum psychosis: a valuable misnomer. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(2):102-103. doi:10.1177/0004867414564698

Auditory hallucinations in a patient who is hearing impaired

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

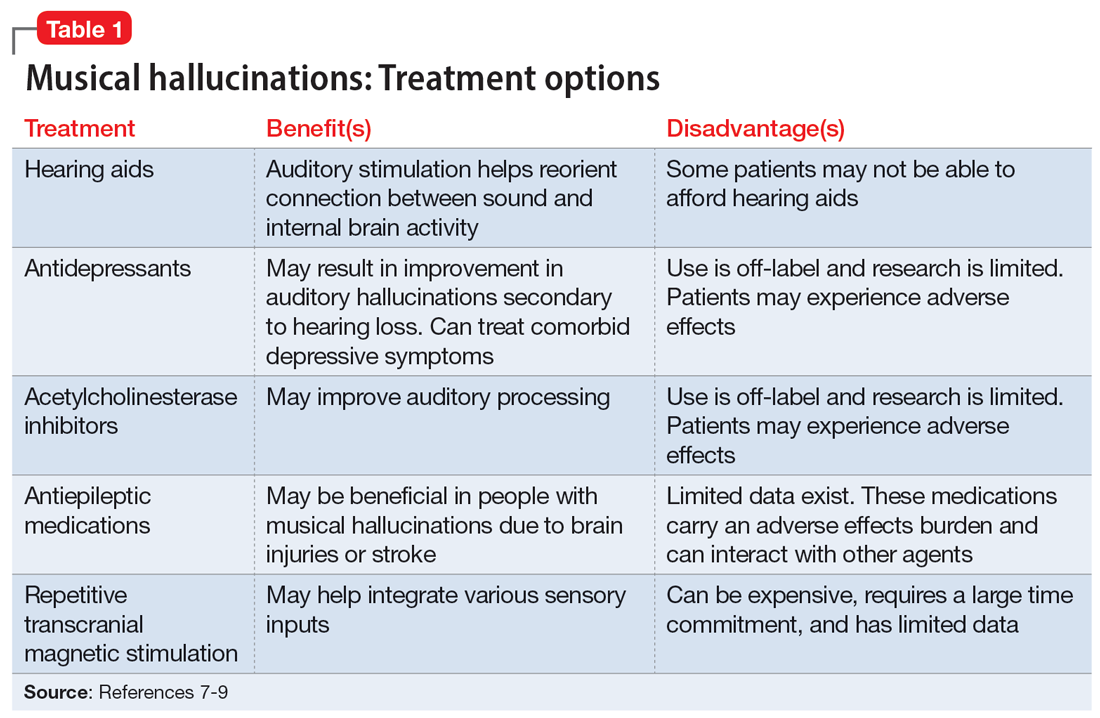

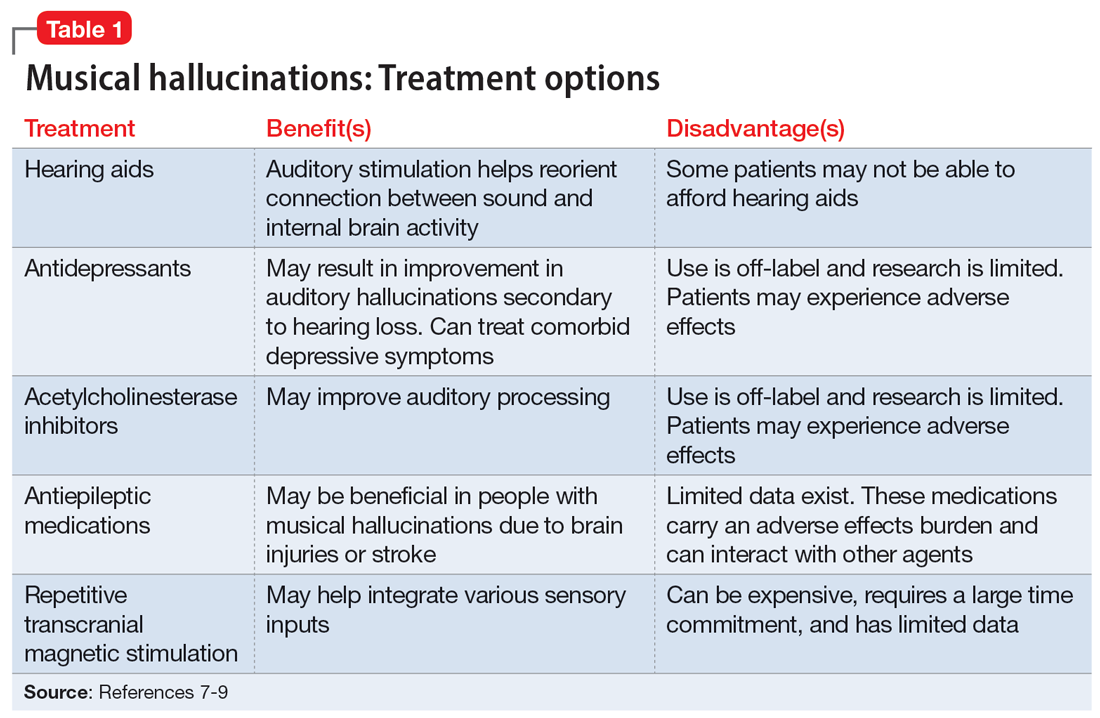

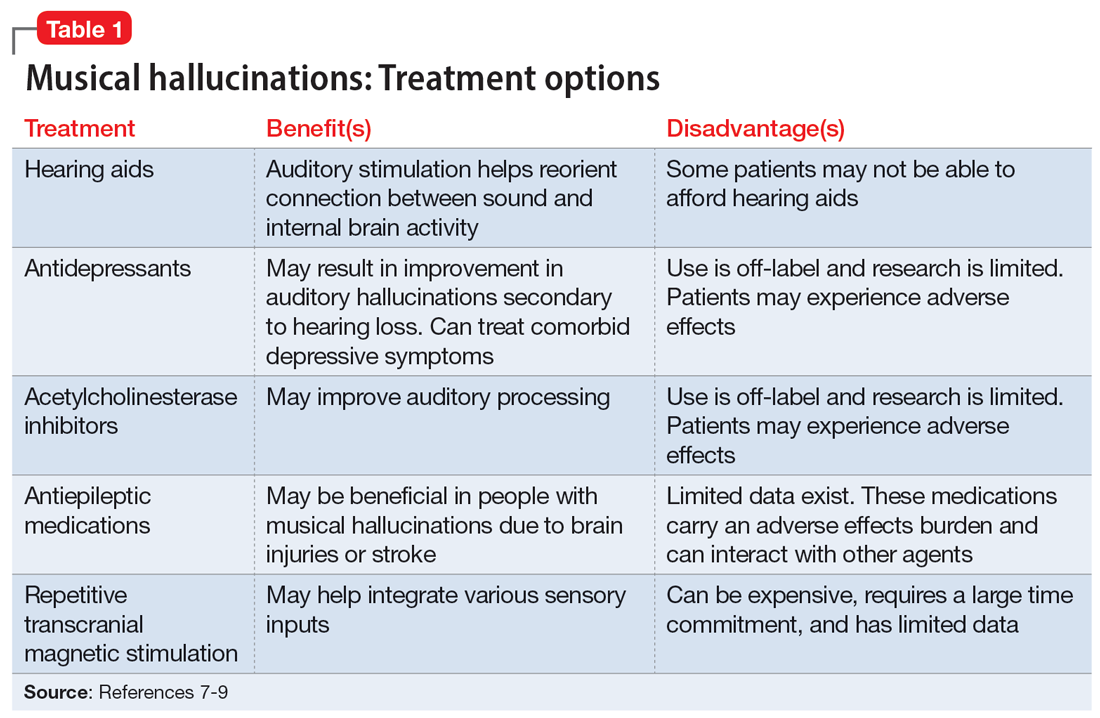

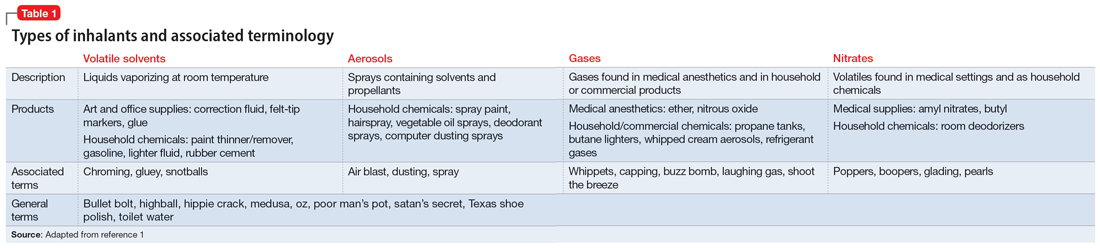

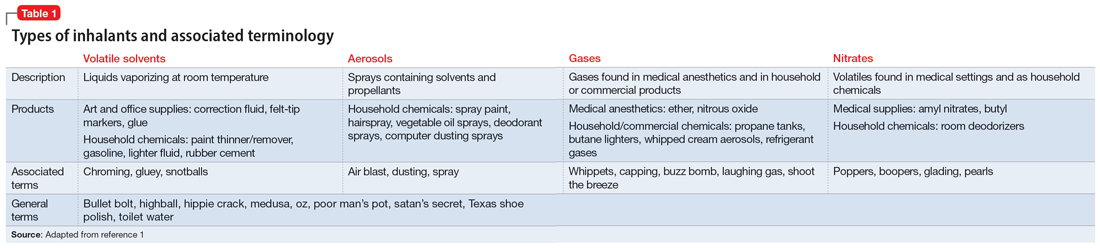

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

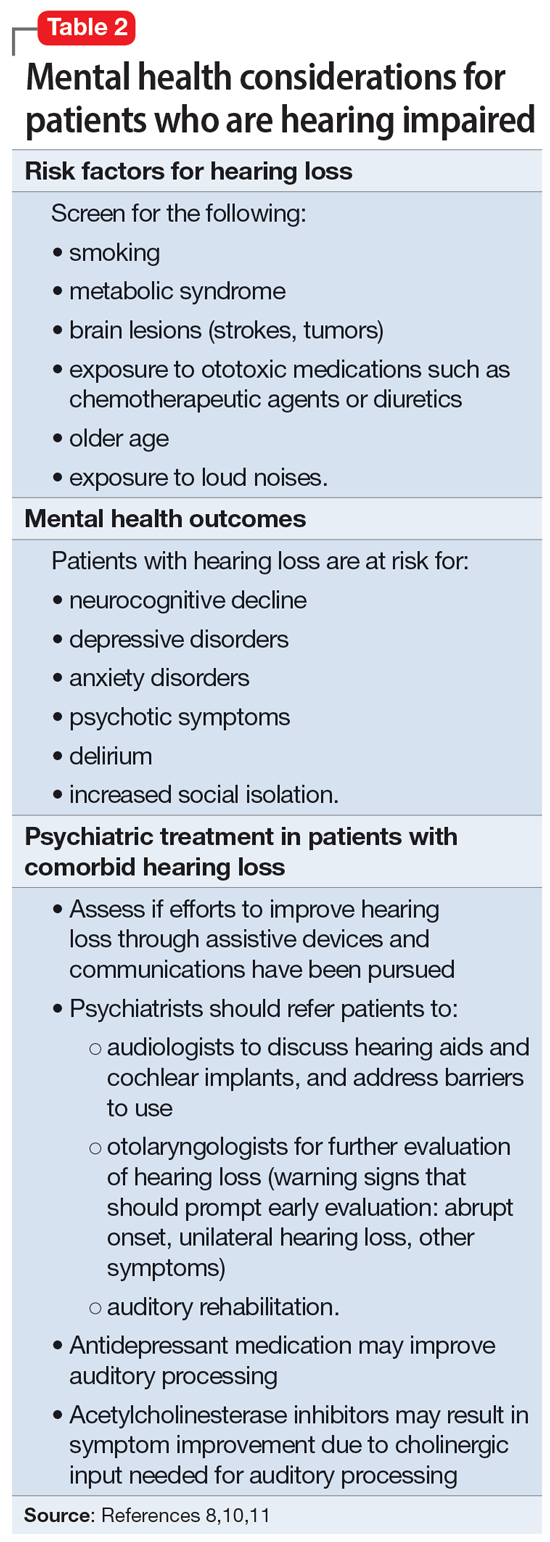

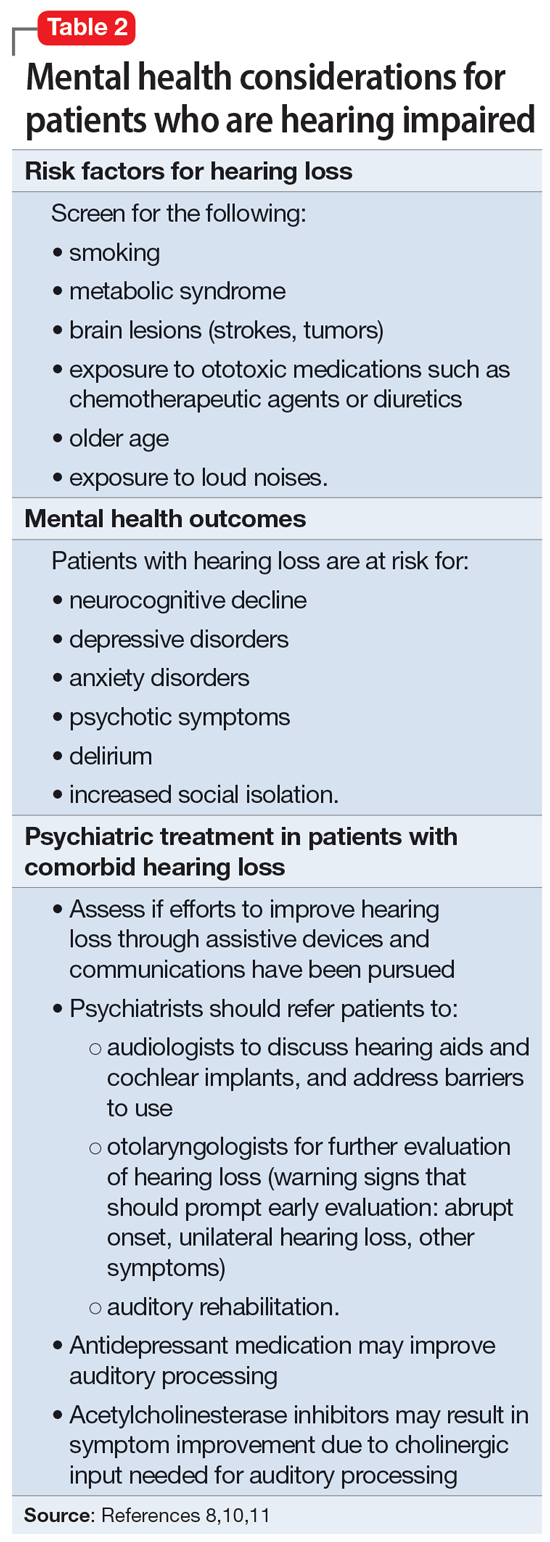

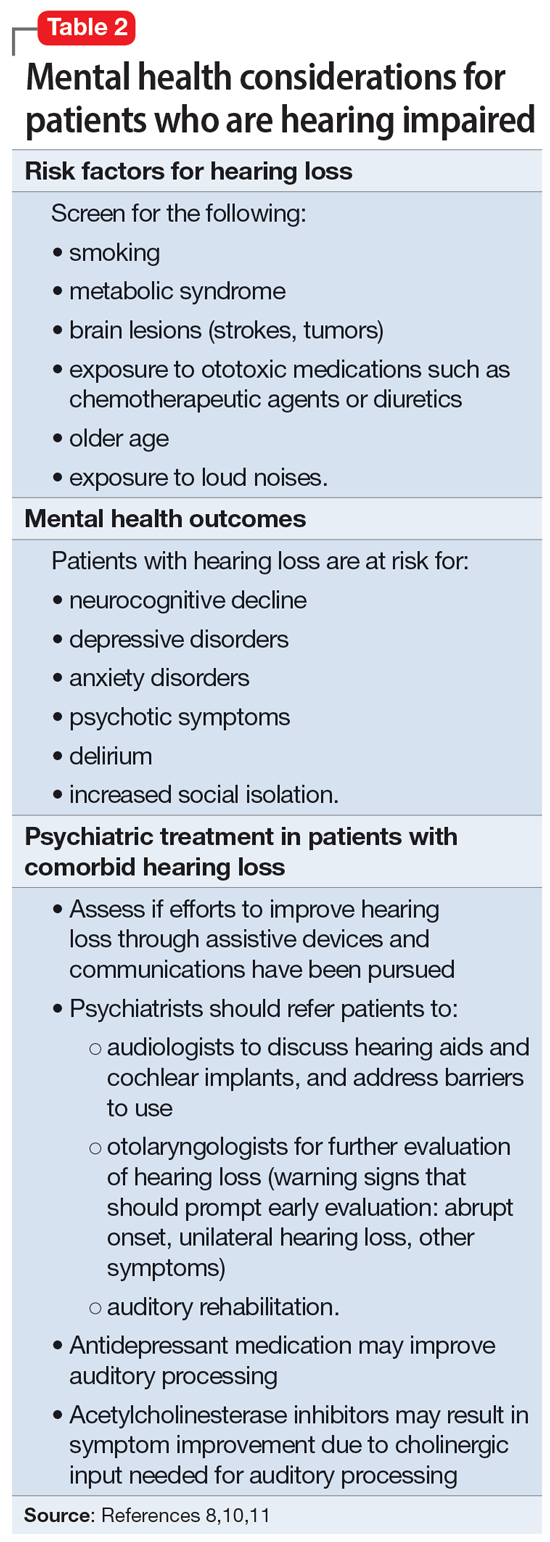

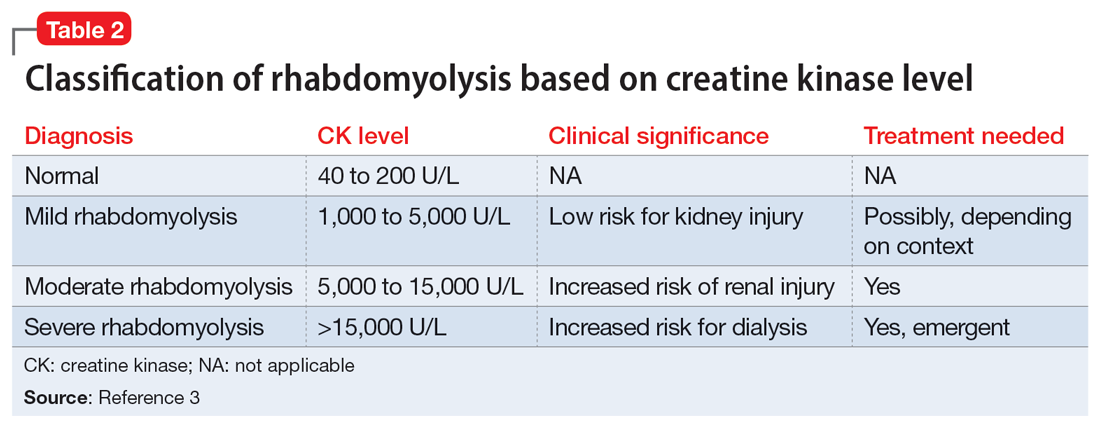

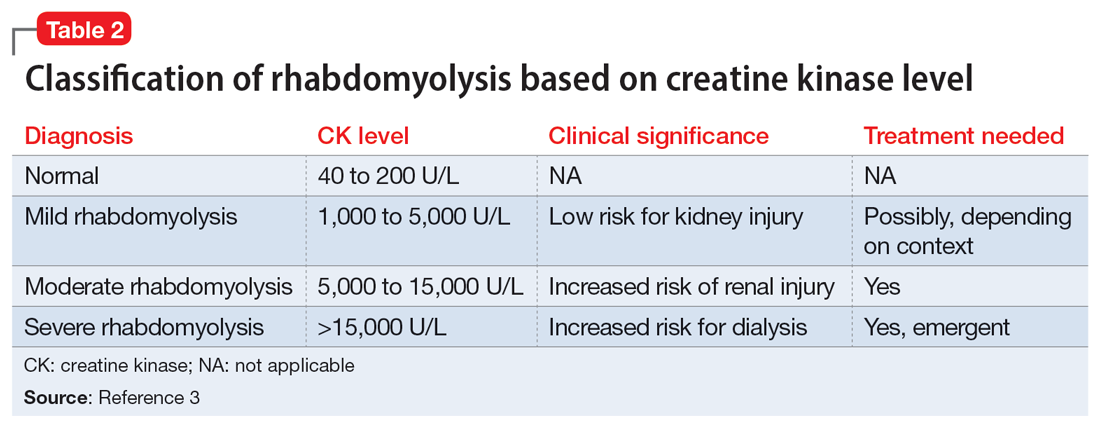

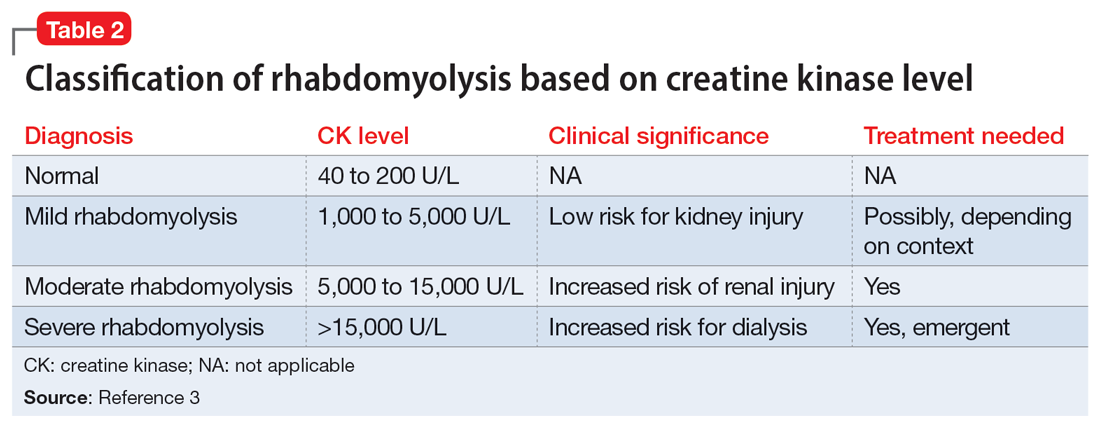

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

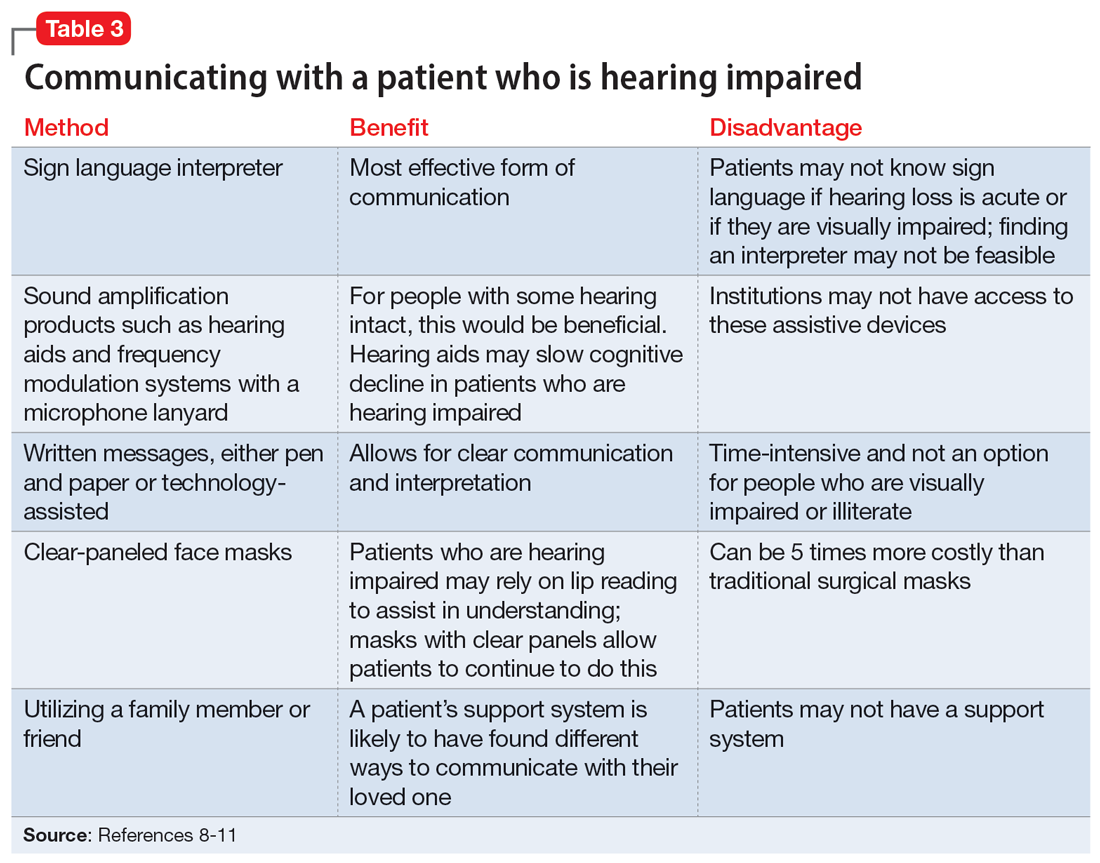

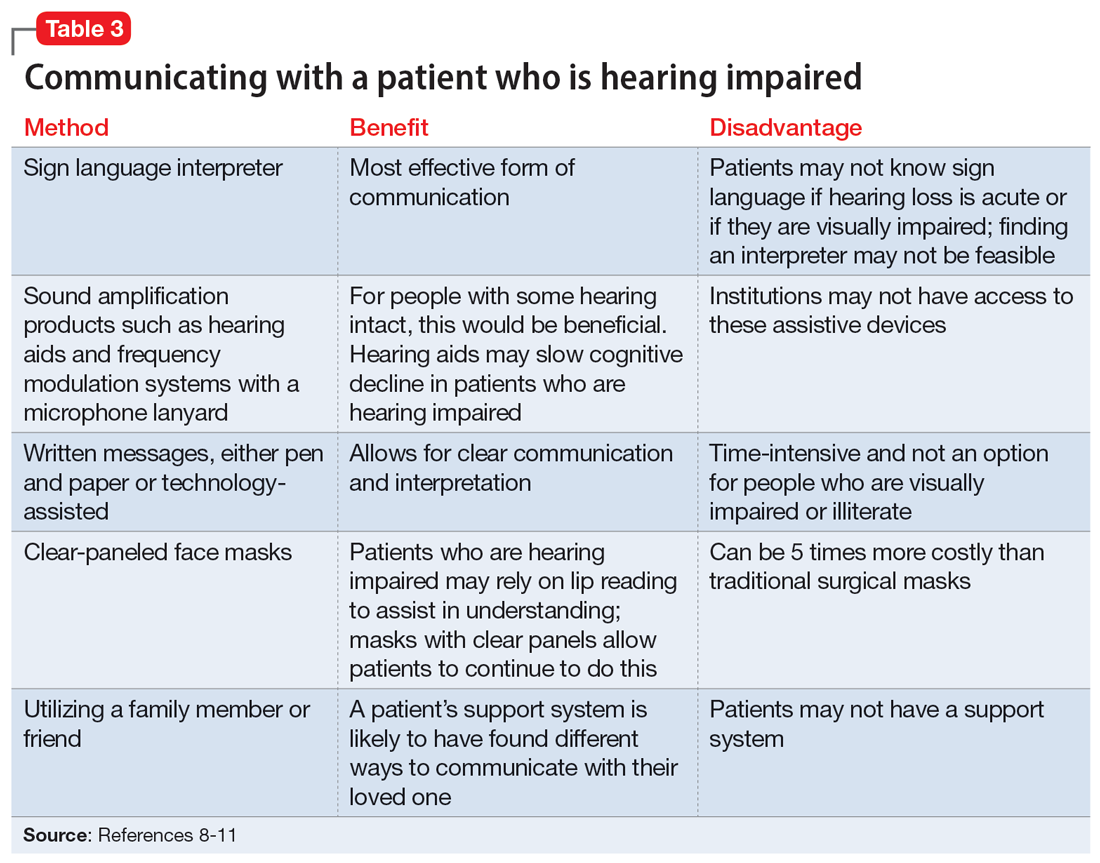

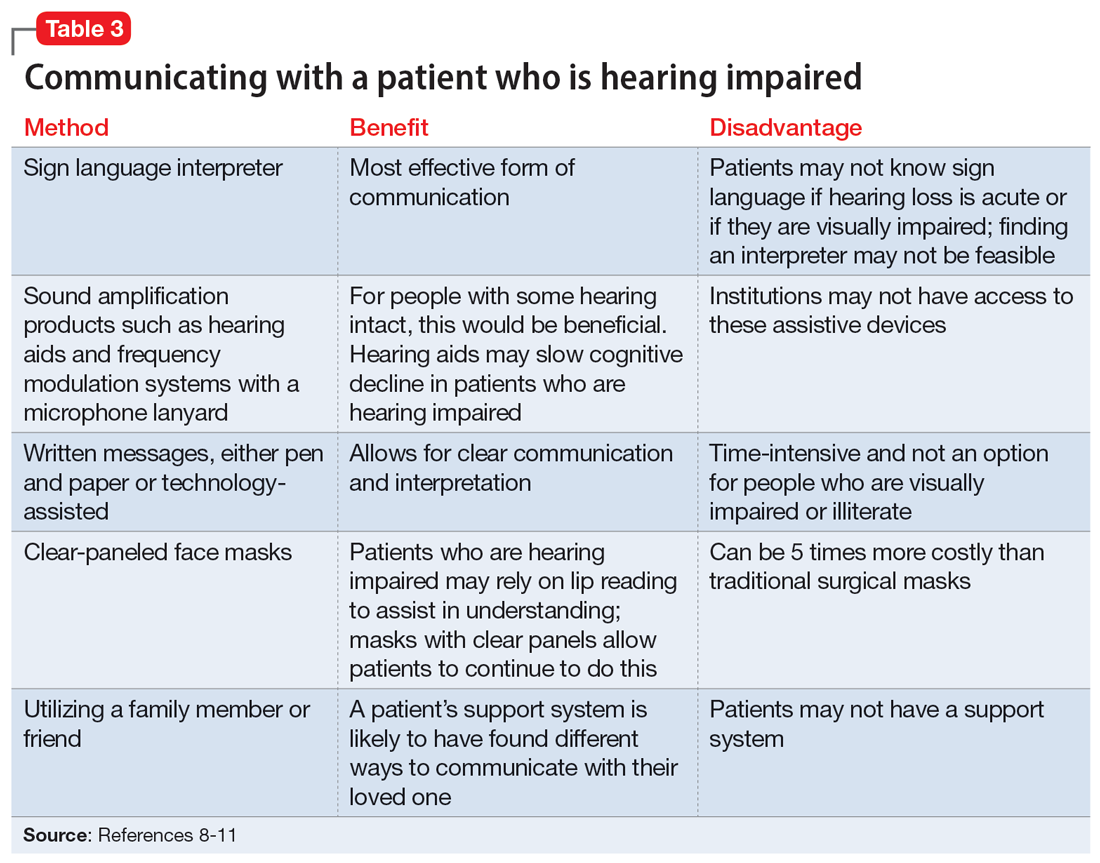

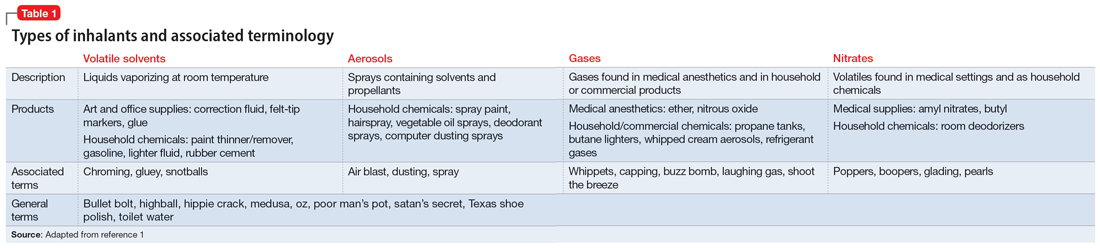

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

1. Cole MG, Dowson L, Dendukuri N, et al. The prevalence and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations among elderly subjects attending an audiology clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):444-452. doi:10.1002/gps.618

2. Alvarez Perez P, Garcia-Antelo MJ, Rubio-Nazabal E. “Doctor, I hear music”: a brief review about musical hallucinations. Open Neurol J. 2017;11:11-14. doi:10.2174/1874205X01711010011

3. Sanchez TG, Rocha SCM, Knobel KAB, et al. Musical hallucination associated with hearing loss. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(2B):395-400. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2011000300024

4. Teunisse RJ, Olde Rikkert MGM. Prevalence of musical hallucinations in patients referred for audiometric testing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(12):1075-1077. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823e31c4

5. Warner N, Aziz V. Hymns and arias: musical hallucinations in older people in Wales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(7):658-660. doi:10.1002/gps.1338

6. Low WK, Tham CA, D’Souza VD, et al. Musical ear syndrome in adult cochlear implant patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(9):854-858. doi:10.1017/S0022215113001758

7. Brunner JP, Amedee RG. Musical hallucinations in a patient with presbycusis: a case report. Ochsner J. 2015;15(1):89-91.

8. Coebergh JAF, Lauw RF, Bots R, et al. Musical hallucinations: review of treatment effects. Front Psychol. 2015;6:814. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00814

9. Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA. Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2069-2072. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.027

10. Shukla A, Nieman CL, Price C, et al. Impact of hearing loss on patient-provider communication among hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Am J Med Qual. 2019;34(3):284-292. doi:10.1177/1062860618798926

11. Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003409

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up

A home health worker visits Ms. L, communicating with her using voice-to-text. Ms. L has not yet gone to her primary care physician, audiologist, or outpatient psychiatrist for follow-up because she needs to arrange transportation. Ms. L remains distressed by the music she is hearing, which is worse at night, along with her acute hearing loss.

Bottom Line

Hearing loss can predispose a person to psychiatric disorders and symptoms, including depression, delirium, and auditory hallucinations. Psychiatrists should strive to ensure clear communication with patients who are hearing impaired and should refer such patients to appropriate resources to improve outcomes.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- Sosland MD, Pinninti N. 5 ways to quiet auditory hallucinations. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(4):110.

- Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, et al. A smartphone app to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(6):798-804. doi:10.1089/ tmj.2019.0109

Drug Brand Names

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Prednisone • Rayos

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valacyclovir • Valtrex

CASE New-onset auditory hallucinations

Ms. L, age 78, presents to our hospital with worsening anxiety due to auditory hallucinations. She has been hearing music, which she reports is worse at night and consists of songs, usually the song Jingle Bells, sometimes just melodies and other times with lyrics. Ms. L denies paranoia, visual hallucinations, or worsening mood.

Two weeks ago, Ms. L had visited another hospital, describing 5 days of right-side hearing loss accompanied by pain and burning in her ear and face, along with vesicular lesions in a dermatomal pattern extending into her auditory canal. During this visit, Ms. L’s complete blood count, urine culture, urine drug screen, electrolytes, liver panel, thyroid studies, and vitamin levels were unremarkable. A CT scan of her head showed no abnormalities.

Ms. L was diagnosed with Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus), which affects cranial nerves, because of physical examination findings with a dermatomal pattern of lesion distribution and associated pain. Ramsay Hunt syndrome can cause facial paralysis and hearing loss in the affected ear. She was discharged with prescriptions for prednisone 60 mg/d for 7 days and valacyclovir 1 g/d for 7 days and told to follow up with her primary care physician. During the present visit to our hospital, Ms. L’s home health nurse reports that she still has her entire bottles of valacyclovir and prednisone left. Ms. L also has left-side hearing loss that began 5 years ago and a history of recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder. Due to the recent onset of right-side hearing loss, her hearing impairment requires her to communicate via writing or via a voice-to-text app.

HISTORY Depressed and living alone

Ms. L was diagnosed with MDD more than 4 decades ago and has been receiving medication since then. She reports no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, suicide attempts, manic symptoms, or psychotic symptoms. For more than 20 years, she has seen a nurse practitioner, who had prescribed mirtazapine 30 mg/d for MDD, poor appetite, and sleep. Within the last 5 years, her nurse practitioner added risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night to augment the mirtazapine for tearfulness, irritability, and mood swings.

Ms. L’s medical history also includes hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She is a retired teacher and lives alone. She has a chore worker who visits her home for 1 hour 5 days a week to help with cleaning and lifting, and support from her son. Ms. L no longer drives and relies on others for transportation, but is able to manage her finances, activities of daily living, cooking, and walking without any assistance.

[polldaddy:12807642]

EVALUATION Identifying the cause of the music

Ms. L is alert and oriented to time and situation, her concentration is appropriate, and her recent and remote memories are preserved. A full cognitive screen is not performed, but she is able to spell WORLD forwards and backwards and adequately perform a serial 7s test. An examination of her ear does not reveal any open vesicular lesions or swelling, but she continues to report pain and tingling in the C7 dermatomal pattern. Her urine drug screen and infectious and autoimmune laboratory testing are unremarkable. She does not have electrolyte, renal function, or blood count abnormalities. An MRI of her brain that is performed to rule out intracranial pathology due to acute hearing loss shows no acute intracranial abnormalities, with some artifact effect due to motion. Because temporal lobe epilepsy can present with hallucinations,1 an EEG is performed to rule out seizure activity; it shows a normal wake pattern.

Psychiatry is consulted for management of the auditory hallucinations because Ms. L is distressed by hearing music. Ms. L is evaluated by Neurology and Otolaryngology. Neurology recommends a repeat brain MRI in the outpatient setting after seeing an artifact in the inpatient imaging, as well as follow-up with her primary care physician. Otolaryngology believes her symptoms are secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome with incomplete treatment, which is consistent with the initial diagnosis from her previous hospital visit, and recommends another course of oral corticosteroids, along with Audiology and Otolaryngology follow-up.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

This is the first case we have seen detailing musical hallucinations (MH) secondary to Ramsay Hunt syndrome, although musical hallucinations have been associated with other etiologies of hearing loss. MH is a “release phenomenon” believed to be caused by deprivation of stimulation of the auditory cortex.2 They are categorized as complex auditory hallucinations made up of melodies and rhythms and may be present in up to 2.5% of patients with hearing impairment.1 The condition is mostly seen in older adults because this population is more likely to experience hearing loss. MH is more common among women (70% to 80% of cases) and is highly comorbid with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or (as was the case for Ms. L) MDD.3 Hallucinations secondary to hearing loss may be more common in left-side hearing loss.4 In a 2005 study, Warner et al5 found religious music such as hymns or Christmas carols was most commonly heard, possibly due to repetitive past exposure.

There is no consensus on treatment for MH. Current treatment guidance comes from case reports and case series. Treatment is generally most successful when the etiology of the hallucination is both apparent and treatable, such as an infectious eitiology.3 In the case of MH due to hearing loss, hallucinations may improve following treatment with hearing aids or cochlear implants,1,3,6,7 which is what was advised for Ms. L. Table 17-9 outlines other possible measures for addressing musical hallucinations.

Anticholinesterases, antidepressants, and antiepileptics may provide some benefit.8 However, pharmacotherapy is generally less efficacious and can cause adverse effects, so environmental support and hearing aids may be a safer approach. No medications have been shown to completely cure MH.

TREATMENT Hearing loss management and follow-up

When speaking with the consulting psychiatry team, Ms. L reports her outpatient psychotropic regimen has been helpful. The team decides to continue mirtazapine 30 mg/d and risperidone 0.5 mg/d at night. We recommend that Ms. L discuss tapering off risperidone with her outpatient clinician if they feel it may be indicated to reduce the risk of adverse effects. The treatment team decides not to start corticosteroids due to the risk of steroid-induced psychotic symptoms. The team discusses hallucinations related to hearing loss with Ms. L and advise her to follow up with Audiology and Otolaryngology in the outpatient setting.

The authors’ observations

Approximately 40% of people age >60 struggle with hearing impairment4,9; this impacts their general quality of life and how clinicians communicate with such patients.10 People with hearing loss are more likely to develop feelings of social isolation, depression, and delirium (Table 28,10,11).11

Risk factors for hearing loss include tobacco use, metabolic syndrome, exposure to loud noises, and exposure to certain ototoxic medications such as chemotherapeutic agents.11 As psychiatrists, it is important to identify patients who may be at risk for hearing loss and refer them to the appropriate medical professional. If hearing loss is new onset, refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for a full evaluation. Unilateral hearing loss should warrant further workup because this could be due to an acoustic neuroma.11

When providing care for a patient who uses a hearing aid, discuss adherence, barriers to adherence, and difficulties with adjusting the hearing aid. A referral to an audiologist may help patients address these barriers. Patients with hearing impairment or loss may benefit from auditory rehabilitation programs that provide communication strategies, ways to adapt to hearing loss, and information about different assistive options.11 Such programs are often run by audiologists or speech language pathologists and contain both counseling and group components.

Continue to: Is is critical for psychiatrists...

It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure appropriate communication with patients who are hearing impaired (Table 38-11). The use of assistive devices such as sound amplifiers, written messages, or family members to assist in communication is needed to prevent miscommunication.9-11

OUTCOME Lack of follow-up