User login

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman developed subacute progression of myalgias and subjective weakness in her proximal extremities after starting a new exercise regimen. The patient had a history of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, for which she had taken atorvastatin 40 mg/d for several years before discontinuing it 2 years earlier for unknown reasons. She had been evaluated multiple times in the primary care clinic and emergency department over the previous month. Each time, her strength was minimally reduced in the upper extremities on examination, her renal function and electrolytes were normal, and her creatine kinase (CK) level was elevated (16,000-20,000 U/L; normal range, 26-192 U/L). She was managed conservatively with fluids and given return precautions each time.

After her myalgias and weakness increased in severity, she presented to the emergency department with a muscle strength score of 4/5 in both shoulders, triceps, hip flexors, hip extensors, abductors, and adductors. Her laboratory results were significant for the presence of blood without red blood cells on her urine dipstick test and a CK level of 25,070 U/L. She was admitted for further evaluation of progressive myopathy and given aggressive IV fluid hydration to prevent renal injury based on her history of unilateral renal agenesis.

Infectious disease testing, which included a respiratory virus panel, acute hepatitis panel, HIV screening, Lyme antibody testing, cytomegalovirus DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction, Epstein-Barr virus capsid immunoglobulin M, and anti-streptolysin O, were negative. Electrolytes, inflammatory markers, and kidney function were normal. However, high-sensitivity troponin-T levels were elevated, with a peak value of 216.3 ng/L (normal range, 0-19 ng/L). The patient denied having any chest pain, and her electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were normal. By hospital Day 4, her myalgias and weakness had improved, CK had stabilized (19,000-21,000 U/L), cardiac enzymes had improved, and urinalysis had normalized. She was discharged with a referral to a rheumatologist.

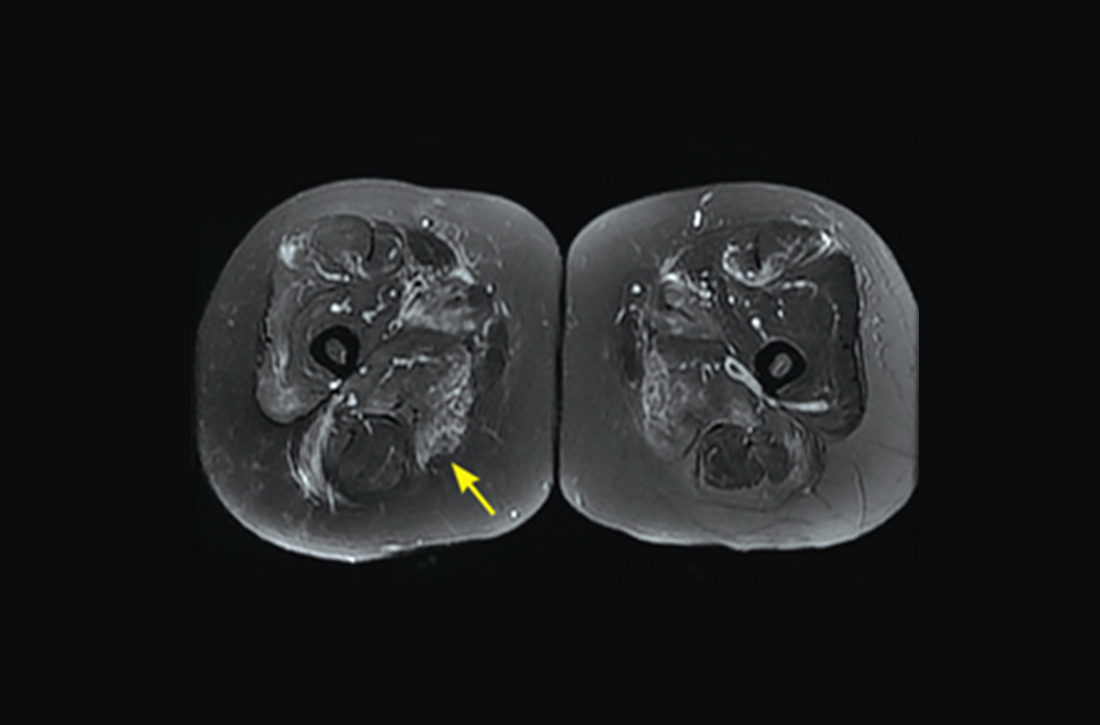

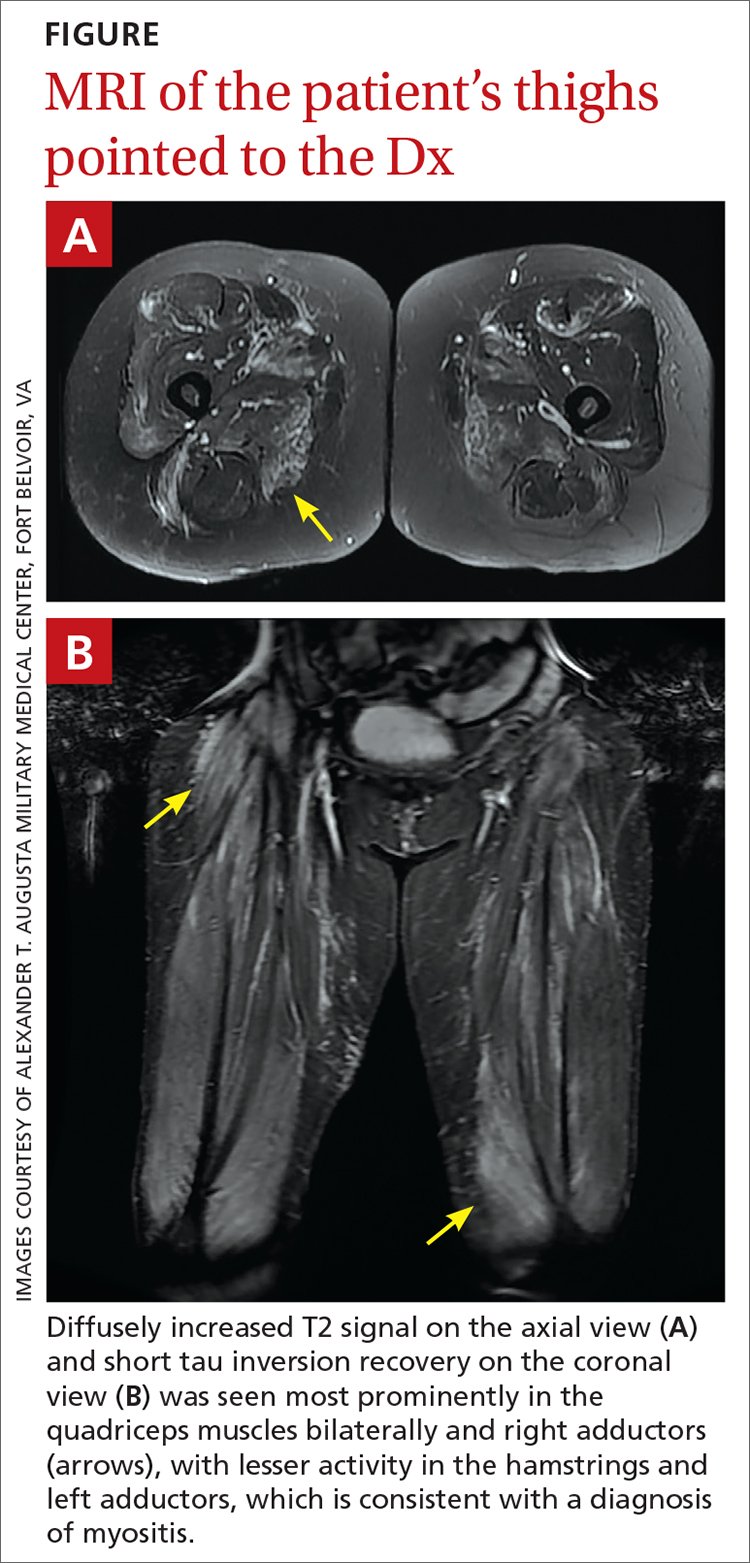

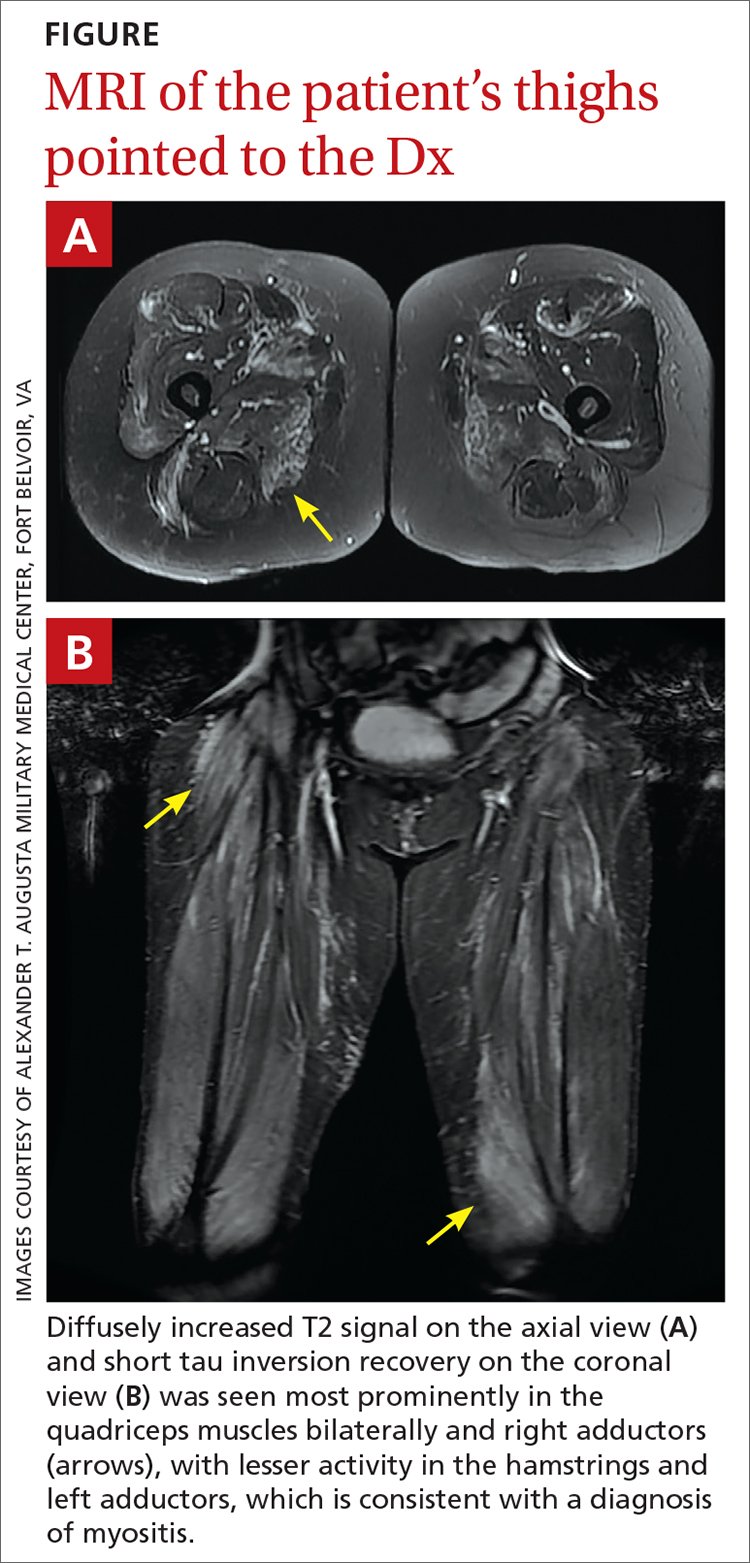

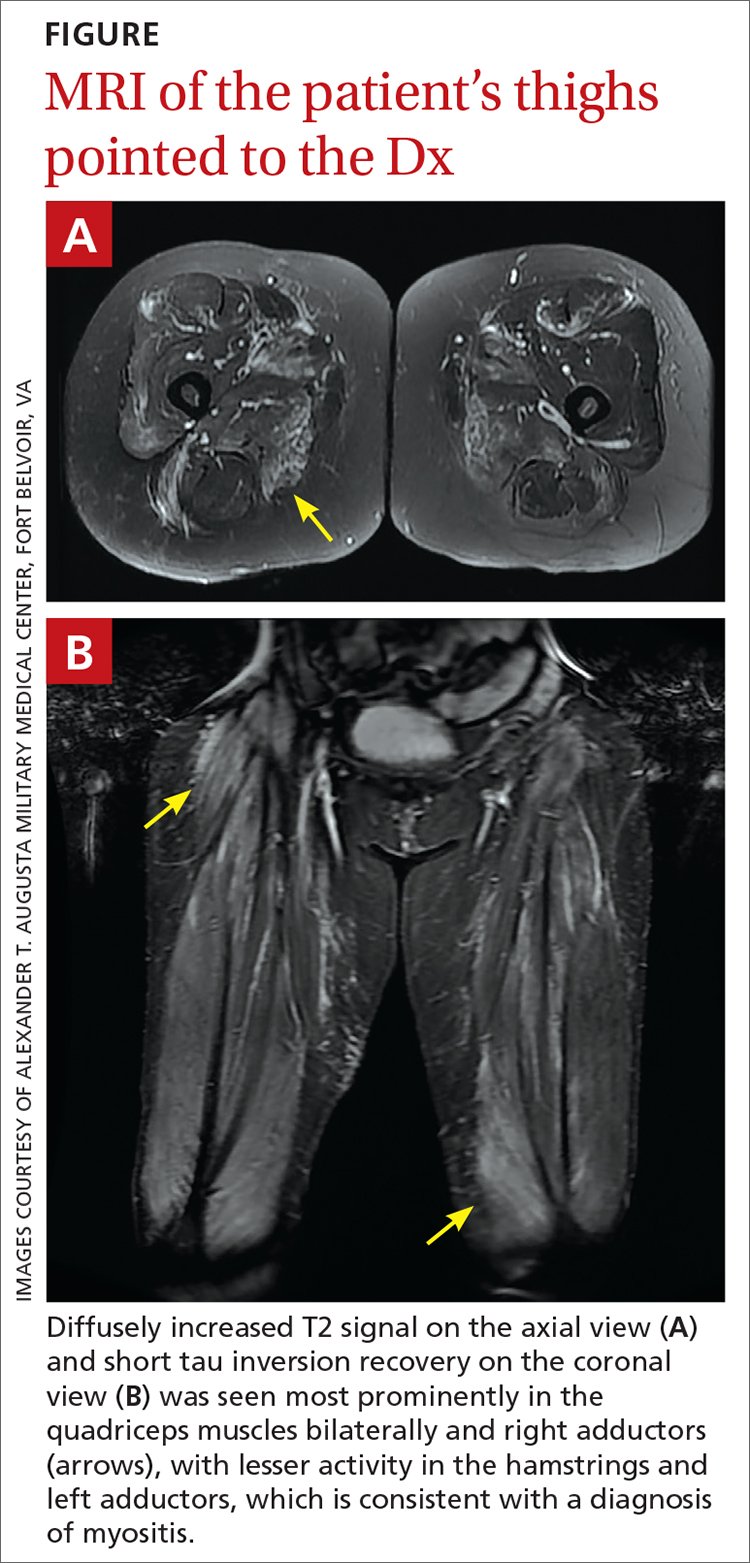

However, 10 days later—before she could see a rheumatologist—she was readmitted to a community hospital for recurrence of severe myalgias, progressive weakness, positive blood on urine dipstick testing, and a rising CK level (to 24,580 U/L) found during a follow-up appointment with her primary care physician. At this point, Neurology and Rheumatology were consulted and myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibody tests were sent out. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her thighs was performed and showed diffusely increased T2 signal and short tau inversion recovery in multiple proximal muscles (FIGURE).

DIAGNOSIS

Given her symmetrical proximal muscle weakness (which was refractory to IV fluid resuscitation), MRI findings, and the exclusion of infection and metabolic derangements, the patient was given a working diagnosis of myositis and treated with 1-g IV methylprednisolone followed by a 4-month steroid taper, methotrexate 20 mg weekly, and physical therapy. This working diagnosis was later confirmed with the results of her autoantibody tests.

At her 1-month follow-up visit, the patient reported minimal improvement in her strength, new neck weakness, and dysphagia with solids. Testing revealed anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR) antibody levels of more than 200 U/L (negative < 20 U/L; positive > 59 U/L), which pointed to a more refined diagnosis of anti-HMGCR immune-mediated necrotizing myositis.

DISCUSSION

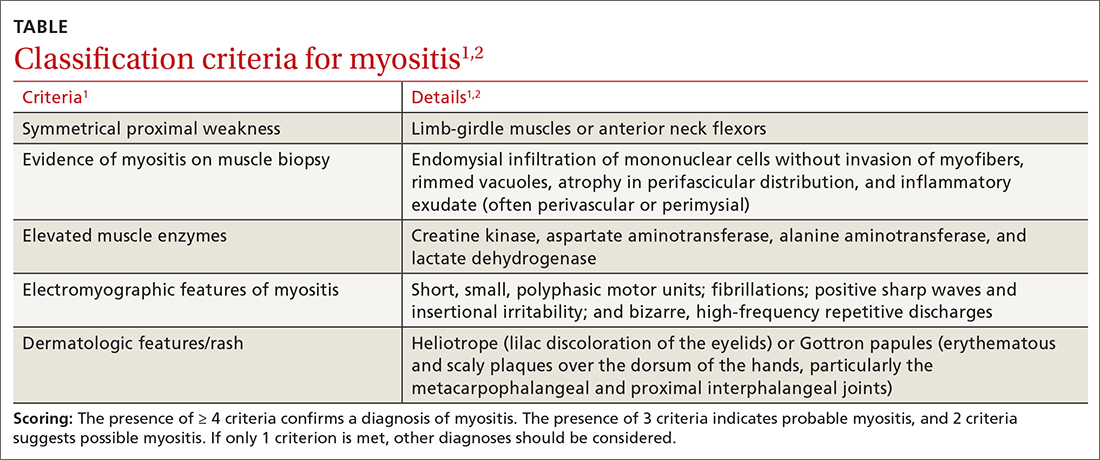

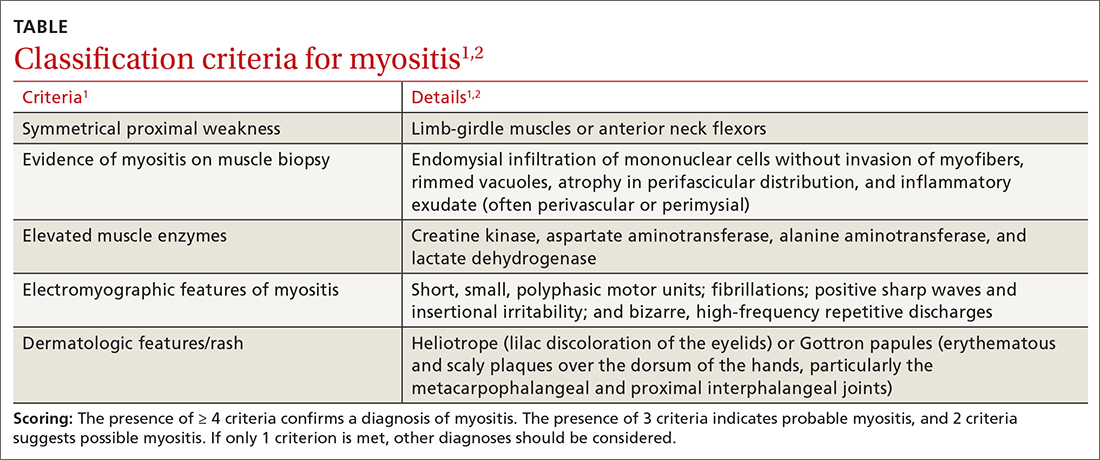

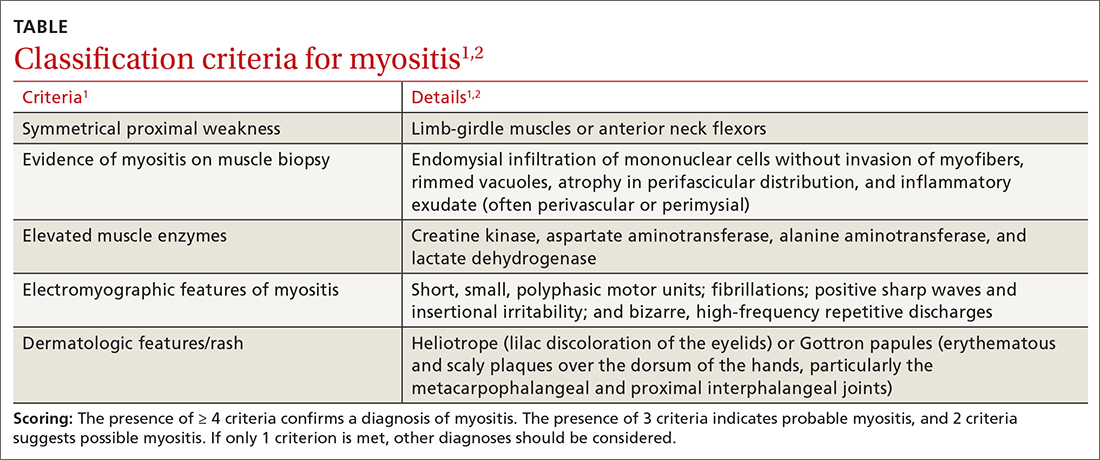

Myositis should be in the differential diagnosis for patients with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness. Bohan and Peter devised a 5-part set of criteria to help diagnose myositis, shown in the TABLE.1,2 This simple framework broadens the differential and guides diagnostic testing. Our patient’s presentation was fairly typical for anti-HMGCR myositis, a subset of immune-mediated necrotizing myositis,3 with a pretest probability of 62% per the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.2 Probability of this diagnosis was further increased by the high-titer anti-HMGCR, so biopsy and electromyography (EMG), as noted by Bohan and Peter, were not pursued.

Continue to: Autoimmune myopathies...

Autoimmune myopathies occur in 9 to 14 per 100,000 people,4 with6% of patients having anti-HMGCR auto-antibodies.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis is more prevalent in older women, patients with type 2 diabetes, and those with a history of atorvastatin use.3,6 Two-thirds of patients with anti-HMGCR myositis report current or prior statin use, and this increases to more than 90% in those age 50 years or older.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis causes significant muscle weakness that does not resolve with discontinuation of the statin and can occur years after the initiation or discontinuation of statin treatment.6 Cardiac involvement is rare4 but dysphagia is relatively common.7,8 Anti-HMGCR myositis also has a weak association with cancer, most commonly gastrointestinal and lung cancers.4,7

Distinguishing statin-induced myalgias from statin-induced myositis guides management. Statin-induced myalgias are associated with normal or slightly increased CK levels (typically < 1000 U/L) and resolve with discontinuation of the statin; the patient can often tolerate re-challenge with a statin.6 In contrast, CK elevation in patients with statin-induced myositis is typically more than 10,000 U/L6 and requires aggressive treatment with immunomodulatory medications to prevent permanent muscle damage.

Treatment recommendations are supported only by case series, observational studies, and expert opinion. Typical first-line treatment includes induction with high-dose corticosteroids followed by prolonged taper plus a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate.4 Maintenance therapy often is achieved with csDMARD therapy for 2 years.4 Severe cases frequently are treated with combination csDMARD therapy (eg, methotrexate and azathioprine or methotrexate and mycophenolate).4 Rituximab and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) are typically reserved for refractory cases.6 Usual monitoring for relapse includes muscle strength testing on examination and evaluation of trending CK levels.8

Our patient received monthly 2-g/kg IVIG infusions, which led to slow, consistent improvement in her strength and normalization of her CK levels to 181 U/L after 6 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

Anti-HMGCR myositis should be suspected in any patient currently or previously treated with a statin who presents with proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, or an elevated CK level. We suggest early subspecialty consultation to discuss whether antibody testing, EMG, or muscle biopsy are warranted. If anti-HMGCR myositis is confirmed, it is advisable to rule out comorbid malignancy and initiate early combination treatment to minimize relapses and permanent muscle damage.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel T. Schoenherr, MD, Family Medicine Residency, National Capital Consortium–Alexander T. Augusta Military Medical Center, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; danieltschoenherr@gmail.com

1. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706

2. Bottai M, Tjärnlund A, Santoni G, et al. EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000507. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000507

3. Basharat P, Lahouti AH, Paik JJ, et al. Statin-induced anti-HMGCR-associated myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:234-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.037

4. Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Mammen AL. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:21. doi: 10.1007/s11926-018-0732-6

5. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:713-721. doi: 10.1002/art.30156

6. Irvine NJ. Anti-HMGCR myopathy: a rare and serious side effect of statins. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:785-788. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.190450

7. Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:72. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0548-6

8. Betteridge Z, McHugh N. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Int Med. 2016;280:8-23. doi: 10.1111/joim.12451

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman developed subacute progression of myalgias and subjective weakness in her proximal extremities after starting a new exercise regimen. The patient had a history of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, for which she had taken atorvastatin 40 mg/d for several years before discontinuing it 2 years earlier for unknown reasons. She had been evaluated multiple times in the primary care clinic and emergency department over the previous month. Each time, her strength was minimally reduced in the upper extremities on examination, her renal function and electrolytes were normal, and her creatine kinase (CK) level was elevated (16,000-20,000 U/L; normal range, 26-192 U/L). She was managed conservatively with fluids and given return precautions each time.

After her myalgias and weakness increased in severity, she presented to the emergency department with a muscle strength score of 4/5 in both shoulders, triceps, hip flexors, hip extensors, abductors, and adductors. Her laboratory results were significant for the presence of blood without red blood cells on her urine dipstick test and a CK level of 25,070 U/L. She was admitted for further evaluation of progressive myopathy and given aggressive IV fluid hydration to prevent renal injury based on her history of unilateral renal agenesis.

Infectious disease testing, which included a respiratory virus panel, acute hepatitis panel, HIV screening, Lyme antibody testing, cytomegalovirus DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction, Epstein-Barr virus capsid immunoglobulin M, and anti-streptolysin O, were negative. Electrolytes, inflammatory markers, and kidney function were normal. However, high-sensitivity troponin-T levels were elevated, with a peak value of 216.3 ng/L (normal range, 0-19 ng/L). The patient denied having any chest pain, and her electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were normal. By hospital Day 4, her myalgias and weakness had improved, CK had stabilized (19,000-21,000 U/L), cardiac enzymes had improved, and urinalysis had normalized. She was discharged with a referral to a rheumatologist.

However, 10 days later—before she could see a rheumatologist—she was readmitted to a community hospital for recurrence of severe myalgias, progressive weakness, positive blood on urine dipstick testing, and a rising CK level (to 24,580 U/L) found during a follow-up appointment with her primary care physician. At this point, Neurology and Rheumatology were consulted and myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibody tests were sent out. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her thighs was performed and showed diffusely increased T2 signal and short tau inversion recovery in multiple proximal muscles (FIGURE).

DIAGNOSIS

Given her symmetrical proximal muscle weakness (which was refractory to IV fluid resuscitation), MRI findings, and the exclusion of infection and metabolic derangements, the patient was given a working diagnosis of myositis and treated with 1-g IV methylprednisolone followed by a 4-month steroid taper, methotrexate 20 mg weekly, and physical therapy. This working diagnosis was later confirmed with the results of her autoantibody tests.

At her 1-month follow-up visit, the patient reported minimal improvement in her strength, new neck weakness, and dysphagia with solids. Testing revealed anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR) antibody levels of more than 200 U/L (negative < 20 U/L; positive > 59 U/L), which pointed to a more refined diagnosis of anti-HMGCR immune-mediated necrotizing myositis.

DISCUSSION

Myositis should be in the differential diagnosis for patients with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness. Bohan and Peter devised a 5-part set of criteria to help diagnose myositis, shown in the TABLE.1,2 This simple framework broadens the differential and guides diagnostic testing. Our patient’s presentation was fairly typical for anti-HMGCR myositis, a subset of immune-mediated necrotizing myositis,3 with a pretest probability of 62% per the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.2 Probability of this diagnosis was further increased by the high-titer anti-HMGCR, so biopsy and electromyography (EMG), as noted by Bohan and Peter, were not pursued.

Continue to: Autoimmune myopathies...

Autoimmune myopathies occur in 9 to 14 per 100,000 people,4 with6% of patients having anti-HMGCR auto-antibodies.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis is more prevalent in older women, patients with type 2 diabetes, and those with a history of atorvastatin use.3,6 Two-thirds of patients with anti-HMGCR myositis report current or prior statin use, and this increases to more than 90% in those age 50 years or older.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis causes significant muscle weakness that does not resolve with discontinuation of the statin and can occur years after the initiation or discontinuation of statin treatment.6 Cardiac involvement is rare4 but dysphagia is relatively common.7,8 Anti-HMGCR myositis also has a weak association with cancer, most commonly gastrointestinal and lung cancers.4,7

Distinguishing statin-induced myalgias from statin-induced myositis guides management. Statin-induced myalgias are associated with normal or slightly increased CK levels (typically < 1000 U/L) and resolve with discontinuation of the statin; the patient can often tolerate re-challenge with a statin.6 In contrast, CK elevation in patients with statin-induced myositis is typically more than 10,000 U/L6 and requires aggressive treatment with immunomodulatory medications to prevent permanent muscle damage.

Treatment recommendations are supported only by case series, observational studies, and expert opinion. Typical first-line treatment includes induction with high-dose corticosteroids followed by prolonged taper plus a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate.4 Maintenance therapy often is achieved with csDMARD therapy for 2 years.4 Severe cases frequently are treated with combination csDMARD therapy (eg, methotrexate and azathioprine or methotrexate and mycophenolate).4 Rituximab and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) are typically reserved for refractory cases.6 Usual monitoring for relapse includes muscle strength testing on examination and evaluation of trending CK levels.8

Our patient received monthly 2-g/kg IVIG infusions, which led to slow, consistent improvement in her strength and normalization of her CK levels to 181 U/L after 6 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

Anti-HMGCR myositis should be suspected in any patient currently or previously treated with a statin who presents with proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, or an elevated CK level. We suggest early subspecialty consultation to discuss whether antibody testing, EMG, or muscle biopsy are warranted. If anti-HMGCR myositis is confirmed, it is advisable to rule out comorbid malignancy and initiate early combination treatment to minimize relapses and permanent muscle damage.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel T. Schoenherr, MD, Family Medicine Residency, National Capital Consortium–Alexander T. Augusta Military Medical Center, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; danieltschoenherr@gmail.com

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman developed subacute progression of myalgias and subjective weakness in her proximal extremities after starting a new exercise regimen. The patient had a history of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, for which she had taken atorvastatin 40 mg/d for several years before discontinuing it 2 years earlier for unknown reasons. She had been evaluated multiple times in the primary care clinic and emergency department over the previous month. Each time, her strength was minimally reduced in the upper extremities on examination, her renal function and electrolytes were normal, and her creatine kinase (CK) level was elevated (16,000-20,000 U/L; normal range, 26-192 U/L). She was managed conservatively with fluids and given return precautions each time.

After her myalgias and weakness increased in severity, she presented to the emergency department with a muscle strength score of 4/5 in both shoulders, triceps, hip flexors, hip extensors, abductors, and adductors. Her laboratory results were significant for the presence of blood without red blood cells on her urine dipstick test and a CK level of 25,070 U/L. She was admitted for further evaluation of progressive myopathy and given aggressive IV fluid hydration to prevent renal injury based on her history of unilateral renal agenesis.

Infectious disease testing, which included a respiratory virus panel, acute hepatitis panel, HIV screening, Lyme antibody testing, cytomegalovirus DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction, Epstein-Barr virus capsid immunoglobulin M, and anti-streptolysin O, were negative. Electrolytes, inflammatory markers, and kidney function were normal. However, high-sensitivity troponin-T levels were elevated, with a peak value of 216.3 ng/L (normal range, 0-19 ng/L). The patient denied having any chest pain, and her electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were normal. By hospital Day 4, her myalgias and weakness had improved, CK had stabilized (19,000-21,000 U/L), cardiac enzymes had improved, and urinalysis had normalized. She was discharged with a referral to a rheumatologist.

However, 10 days later—before she could see a rheumatologist—she was readmitted to a community hospital for recurrence of severe myalgias, progressive weakness, positive blood on urine dipstick testing, and a rising CK level (to 24,580 U/L) found during a follow-up appointment with her primary care physician. At this point, Neurology and Rheumatology were consulted and myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibody tests were sent out. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her thighs was performed and showed diffusely increased T2 signal and short tau inversion recovery in multiple proximal muscles (FIGURE).

DIAGNOSIS

Given her symmetrical proximal muscle weakness (which was refractory to IV fluid resuscitation), MRI findings, and the exclusion of infection and metabolic derangements, the patient was given a working diagnosis of myositis and treated with 1-g IV methylprednisolone followed by a 4-month steroid taper, methotrexate 20 mg weekly, and physical therapy. This working diagnosis was later confirmed with the results of her autoantibody tests.

At her 1-month follow-up visit, the patient reported minimal improvement in her strength, new neck weakness, and dysphagia with solids. Testing revealed anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR) antibody levels of more than 200 U/L (negative < 20 U/L; positive > 59 U/L), which pointed to a more refined diagnosis of anti-HMGCR immune-mediated necrotizing myositis.

DISCUSSION

Myositis should be in the differential diagnosis for patients with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness. Bohan and Peter devised a 5-part set of criteria to help diagnose myositis, shown in the TABLE.1,2 This simple framework broadens the differential and guides diagnostic testing. Our patient’s presentation was fairly typical for anti-HMGCR myositis, a subset of immune-mediated necrotizing myositis,3 with a pretest probability of 62% per the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.2 Probability of this diagnosis was further increased by the high-titer anti-HMGCR, so biopsy and electromyography (EMG), as noted by Bohan and Peter, were not pursued.

Continue to: Autoimmune myopathies...

Autoimmune myopathies occur in 9 to 14 per 100,000 people,4 with6% of patients having anti-HMGCR auto-antibodies.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis is more prevalent in older women, patients with type 2 diabetes, and those with a history of atorvastatin use.3,6 Two-thirds of patients with anti-HMGCR myositis report current or prior statin use, and this increases to more than 90% in those age 50 years or older.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis causes significant muscle weakness that does not resolve with discontinuation of the statin and can occur years after the initiation or discontinuation of statin treatment.6 Cardiac involvement is rare4 but dysphagia is relatively common.7,8 Anti-HMGCR myositis also has a weak association with cancer, most commonly gastrointestinal and lung cancers.4,7

Distinguishing statin-induced myalgias from statin-induced myositis guides management. Statin-induced myalgias are associated with normal or slightly increased CK levels (typically < 1000 U/L) and resolve with discontinuation of the statin; the patient can often tolerate re-challenge with a statin.6 In contrast, CK elevation in patients with statin-induced myositis is typically more than 10,000 U/L6 and requires aggressive treatment with immunomodulatory medications to prevent permanent muscle damage.

Treatment recommendations are supported only by case series, observational studies, and expert opinion. Typical first-line treatment includes induction with high-dose corticosteroids followed by prolonged taper plus a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate.4 Maintenance therapy often is achieved with csDMARD therapy for 2 years.4 Severe cases frequently are treated with combination csDMARD therapy (eg, methotrexate and azathioprine or methotrexate and mycophenolate).4 Rituximab and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) are typically reserved for refractory cases.6 Usual monitoring for relapse includes muscle strength testing on examination and evaluation of trending CK levels.8

Our patient received monthly 2-g/kg IVIG infusions, which led to slow, consistent improvement in her strength and normalization of her CK levels to 181 U/L after 6 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

Anti-HMGCR myositis should be suspected in any patient currently or previously treated with a statin who presents with proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, or an elevated CK level. We suggest early subspecialty consultation to discuss whether antibody testing, EMG, or muscle biopsy are warranted. If anti-HMGCR myositis is confirmed, it is advisable to rule out comorbid malignancy and initiate early combination treatment to minimize relapses and permanent muscle damage.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel T. Schoenherr, MD, Family Medicine Residency, National Capital Consortium–Alexander T. Augusta Military Medical Center, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; danieltschoenherr@gmail.com

1. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706

2. Bottai M, Tjärnlund A, Santoni G, et al. EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000507. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000507

3. Basharat P, Lahouti AH, Paik JJ, et al. Statin-induced anti-HMGCR-associated myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:234-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.037

4. Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Mammen AL. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:21. doi: 10.1007/s11926-018-0732-6

5. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:713-721. doi: 10.1002/art.30156

6. Irvine NJ. Anti-HMGCR myopathy: a rare and serious side effect of statins. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:785-788. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.190450

7. Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:72. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0548-6

8. Betteridge Z, McHugh N. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Int Med. 2016;280:8-23. doi: 10.1111/joim.12451

1. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706

2. Bottai M, Tjärnlund A, Santoni G, et al. EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000507. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000507

3. Basharat P, Lahouti AH, Paik JJ, et al. Statin-induced anti-HMGCR-associated myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:234-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.037

4. Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Mammen AL. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:21. doi: 10.1007/s11926-018-0732-6

5. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:713-721. doi: 10.1002/art.30156

6. Irvine NJ. Anti-HMGCR myopathy: a rare and serious side effect of statins. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:785-788. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.190450

7. Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:72. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0548-6

8. Betteridge Z, McHugh N. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Int Med. 2016;280:8-23. doi: 10.1111/joim.12451

► Myalgias and progressive symmetrical proximal weakness

► History of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia