User login

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

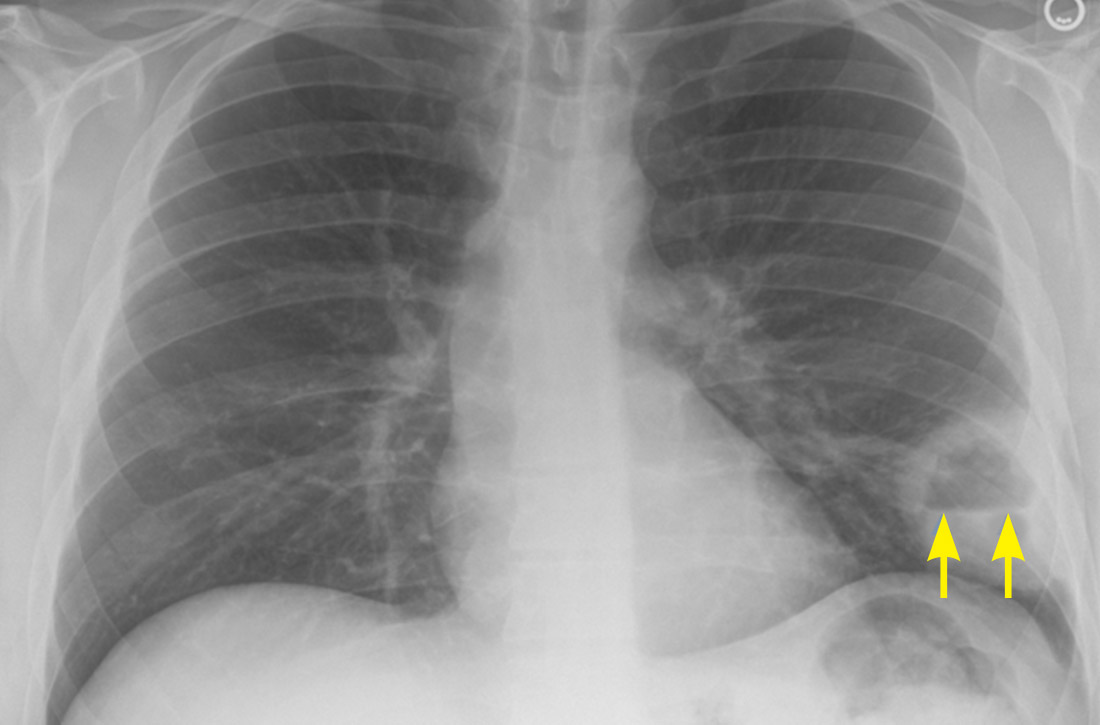

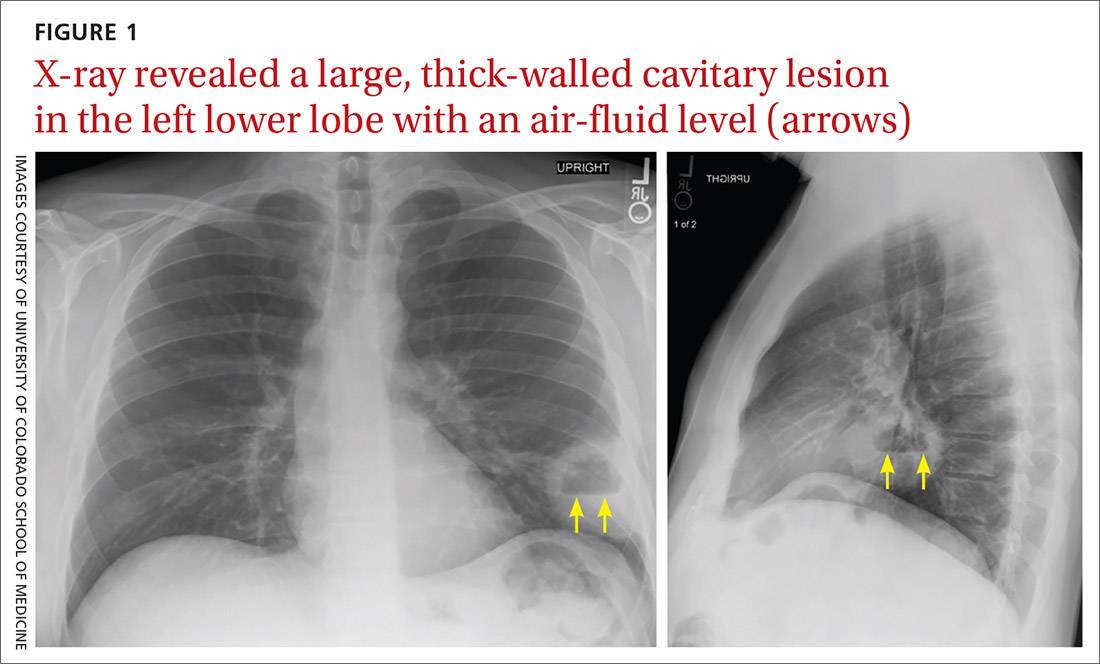

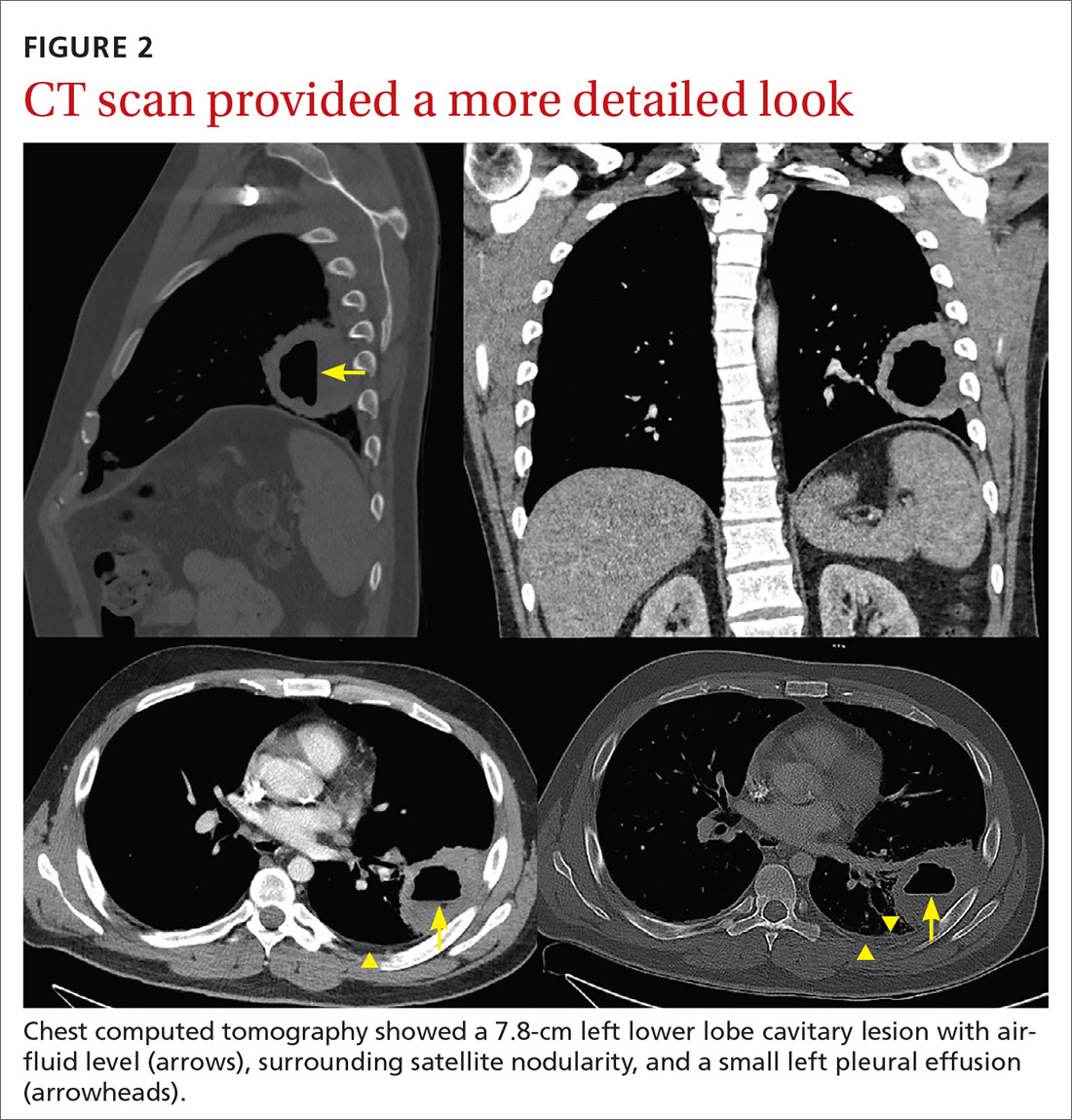

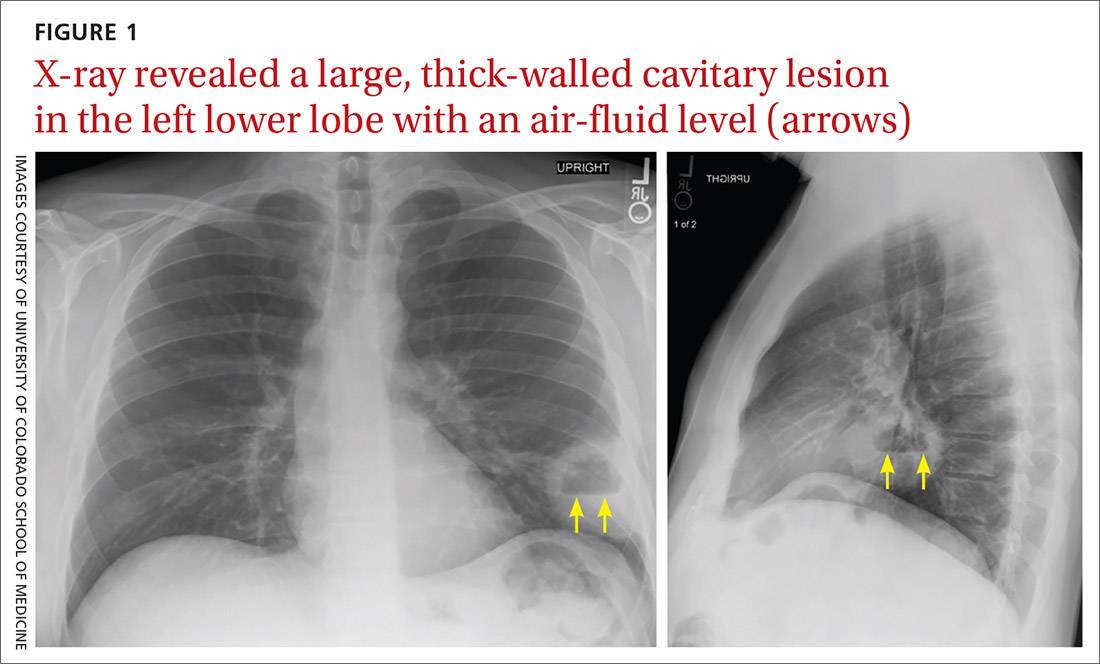

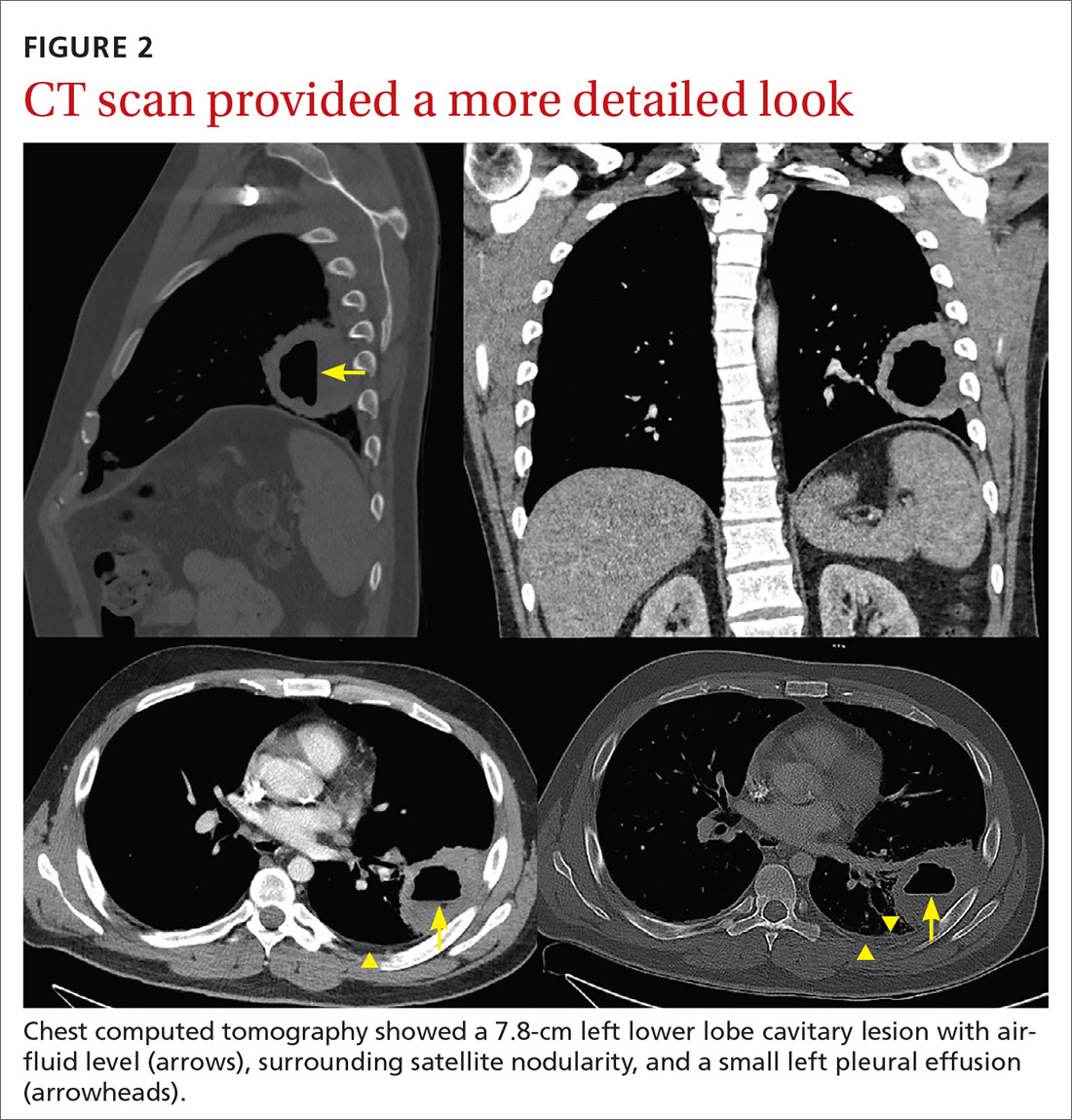

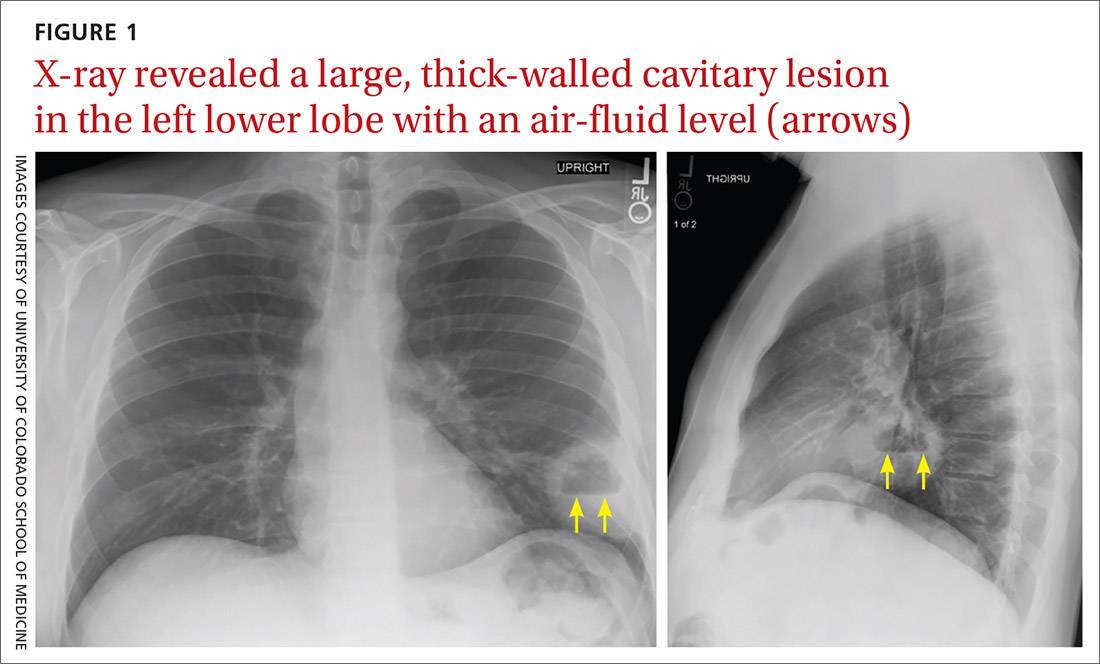

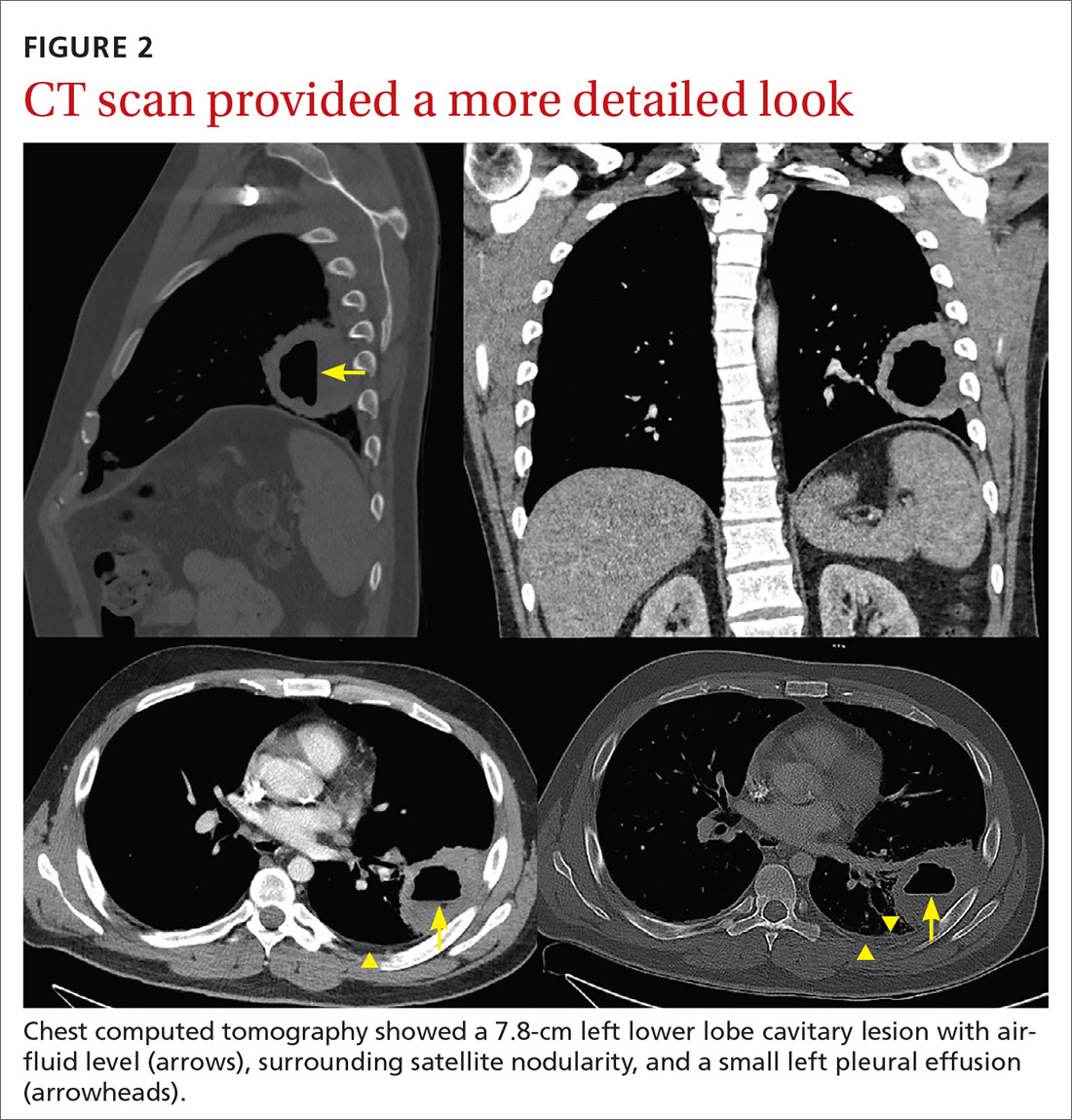

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

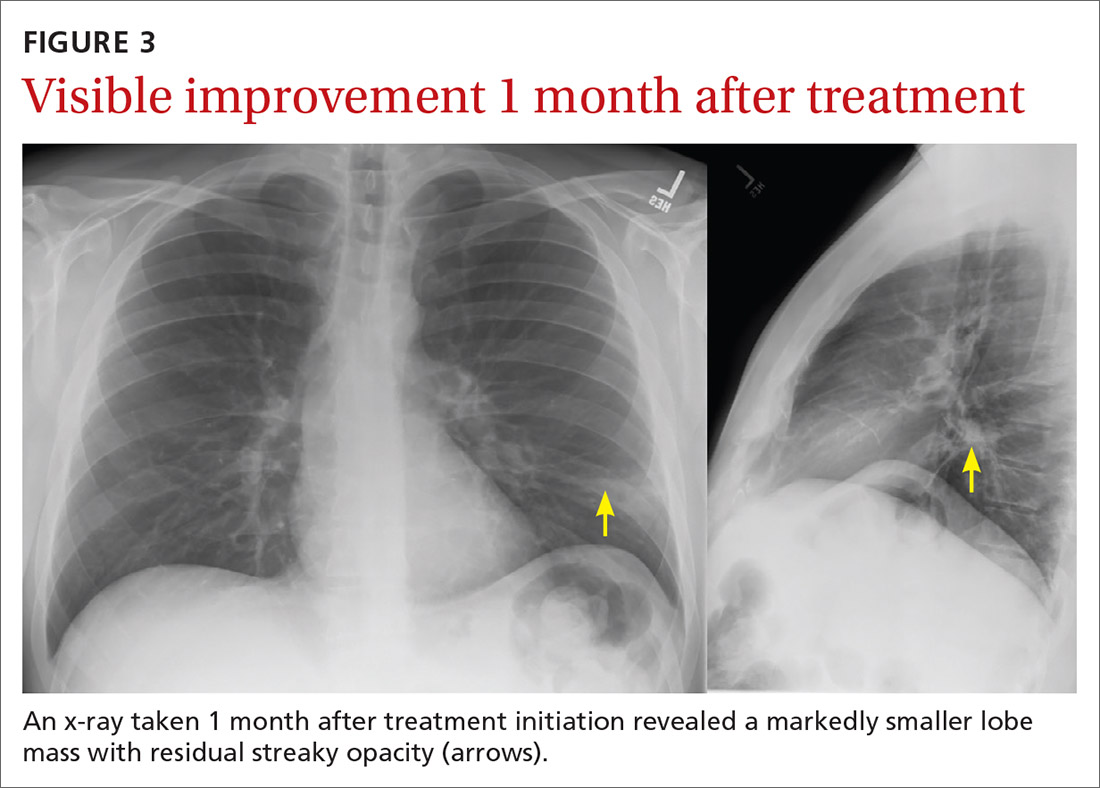

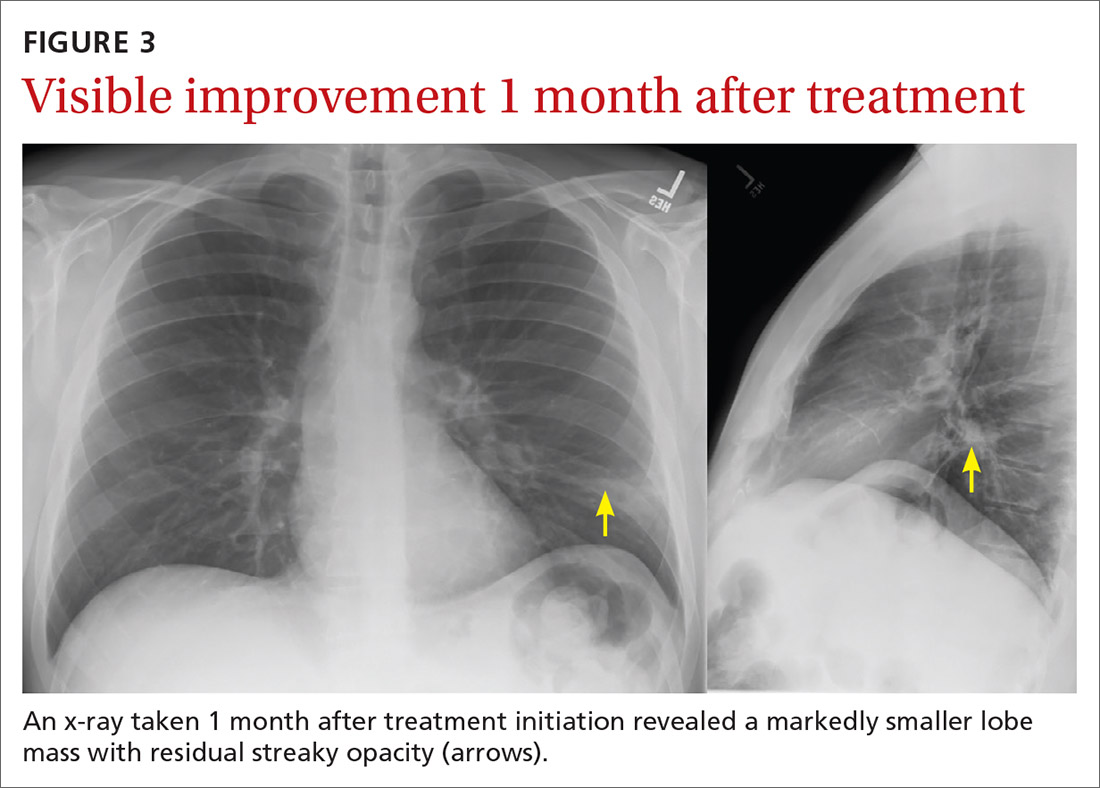

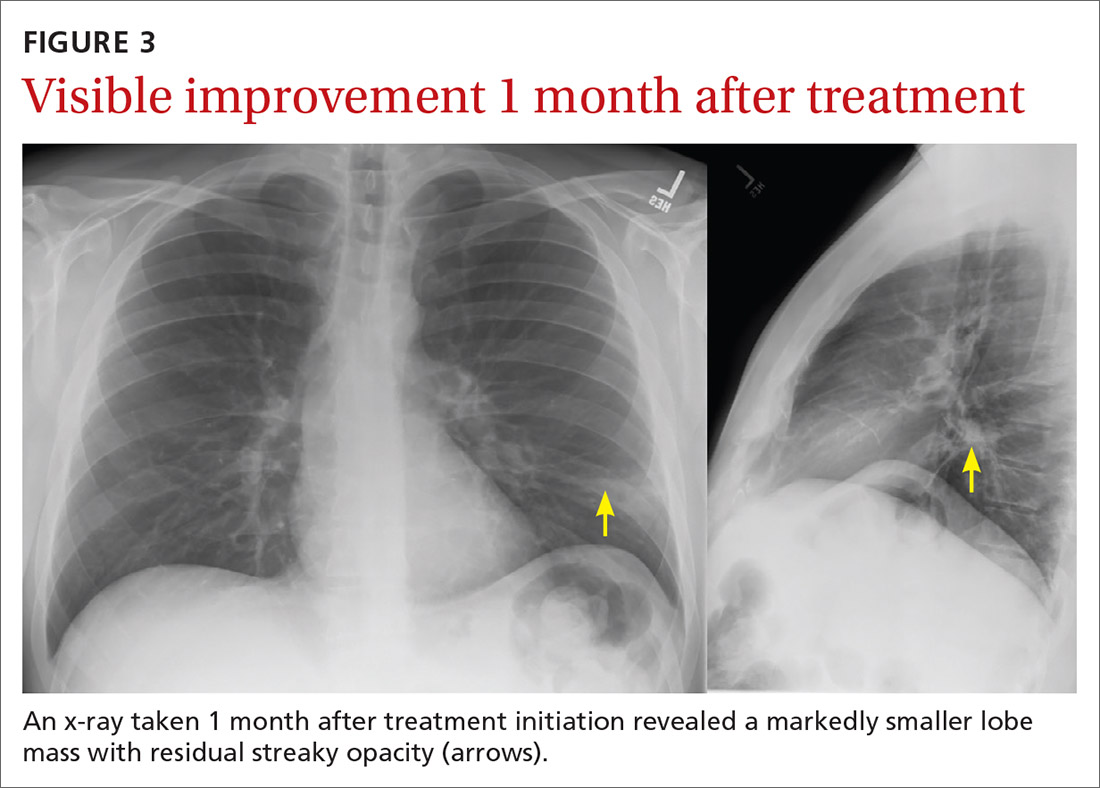

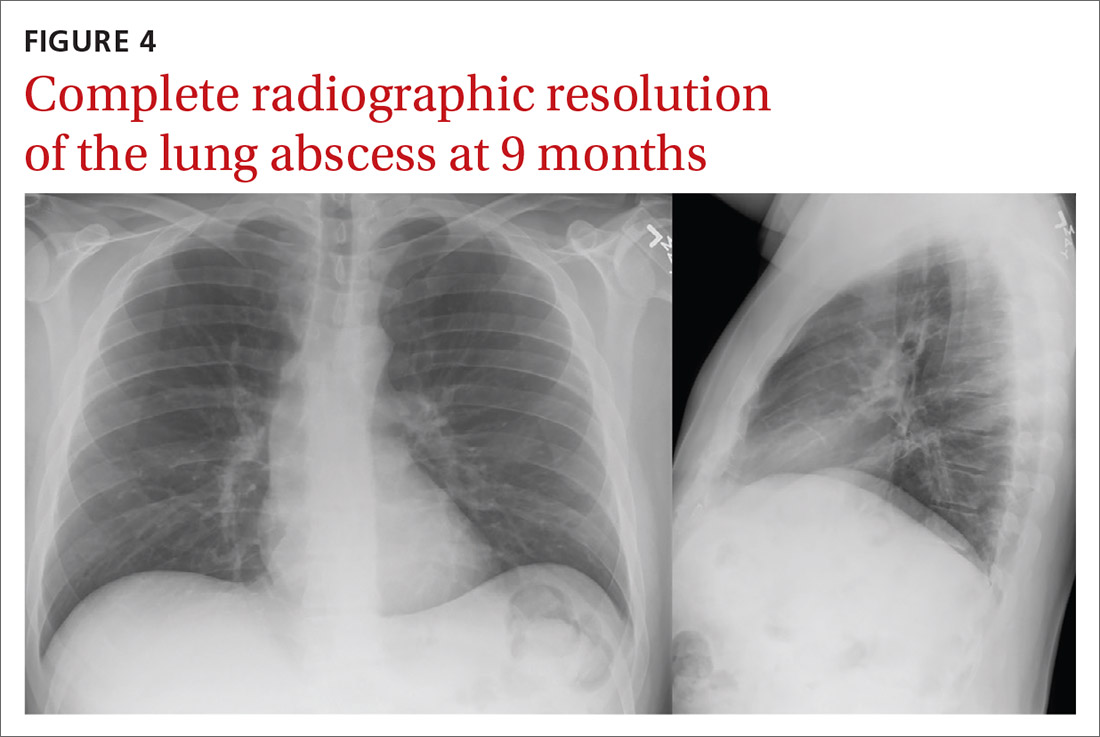

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@cuanschutz.edu

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

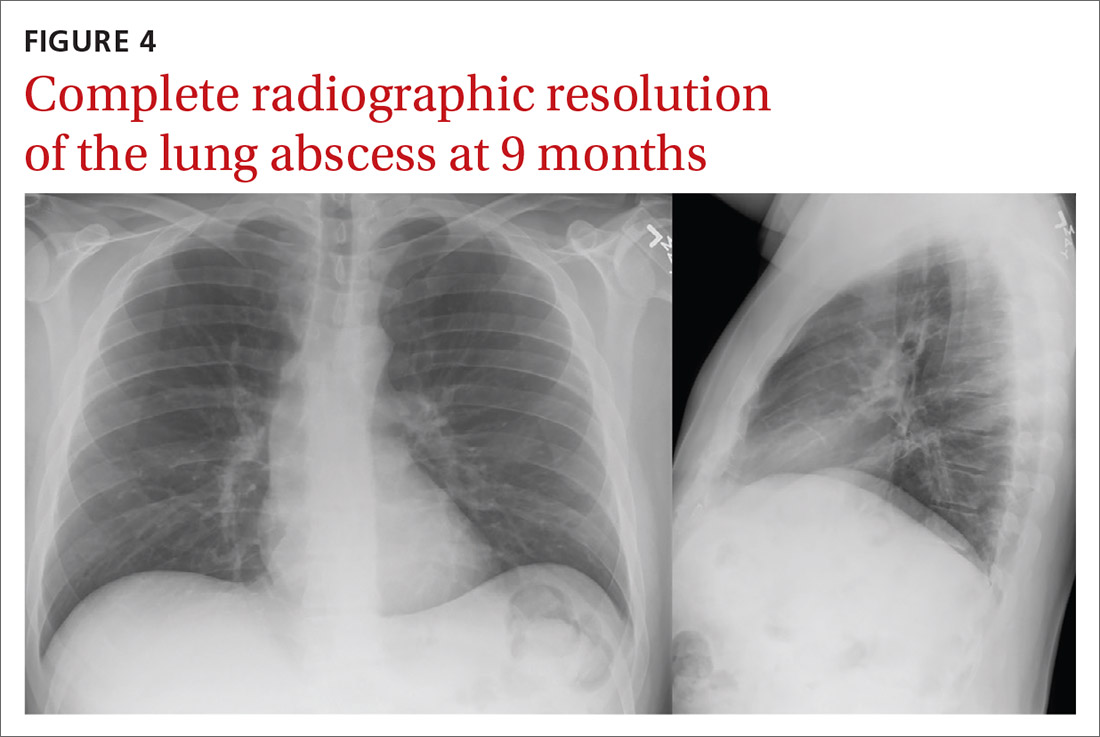

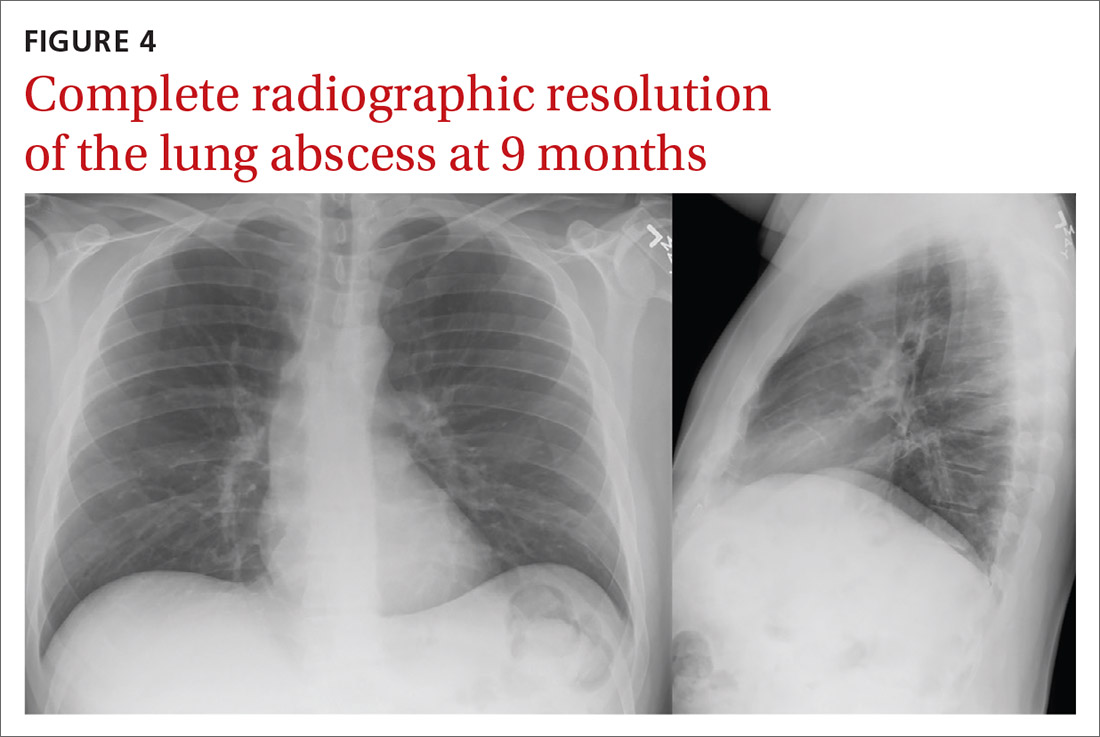

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@cuanschutz.edu

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; morteza.khodaee@cuanschutz.edu

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883