User login

A safer way to use Botox to treat challenging dystonia type?

, new research suggests.

Oromandibular dystonia causes an involuntary opening of the mouth, which can be disabling and disfiguring. Although injection of the lateral pterygoid muscle with botulinum toxin is the preferred treatment for oromandibular dystonia, a potential complication concerns the maxillary artery, which can run either lateral or medial to the lateral pterygoid muscle.

In a study of 200 Turkish patients, researchers documented significant variations between men and women in the anatomical location of the maxillary artery – and even found lateral versus medial differences on the left and right side in the same individual.

“The results showed that the maxillary artery runs lateral to the muscle in 67% of the Turkish patients,” Rezzak Yilmaz, MD, department of neurology, University of Ankara Medical School, Turkey, reported at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Given this high rate, there is a high risk for injury “that may result in pain and hematoma” when using preauricular extraoral injections, Dr. Yilmaz and colleagues noted. Instead, they recommend an intraoral injection approach to the lateral pterygoid muscle. “However, this critical anatomical variation is still unrecognized by most clinicians performing [botulinum toxin] injections,” they wrote.

Significant gender differences

The maxillary artery is the largest branch of the external carotid artery.

In the current study, the researchers used magnetic resonance angiography to assess the relevant anatomy in a cohort of 200 individuals (mean age, 56.4 years; 64% women) without a history of facial trauma or movement disorders.

Results showed that the maxillary artery ran lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle in 67% of the study population.

“This result was also more frequent in females compared with males. Also, there was a considerable variability between the left and the right side in 20% of the participants,” Dr. Yilmaz reported.

Statistically significant gender differences were found for the artery running lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle on both sides (71.1% in women vs. 58.5% in men; P = .007) and for the artery running lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle on just the left side (69.8% in women vs. 53.5% in men; P = .02).

In an email exchange, Dr. Yilmaz said if medical personnel are not trained to perform an intraoral approach, “imaging to visualize the path of the maxillary artery before an extraoral/transcutaneous injection can be recommended.”

“If the imaging reveals that the maxillary artery passes lateral to the muscle, then the patient needs to be referred to another center for an intraoral injection,” unless the clinician is trained for an intraoral approach, he added.

Useful education

Commenting on the study, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the Movement Disorders Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said the results were educational. “I didn’t know about all this variability. I was working under the assumption that the artery was medial,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

Among his large practice of about 2,000 patients, Dr. Tagliati estimated having five patients for whom he provides this type of injection – and has never encountered a problem with them.

“Maybe all my patients are medial, but now that I’m aware I’ll probably pay more attention,” Dr. Tagliati said. He does not currently perform magnetic resonance angiography before injecting them, “although maybe I should,” he said.

When asked if it is worth the time and expense to perform magnetic resonance angiography on every patient who comes in for lateral pterygoid muscle injections, Dr. Tagliati said that although he has done the injections without problems in his current patients, he may “start obtaining imaging studies to make sure that we’re not taking unnecessary risk” if the maxillary artery is lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle in new patients.

If there is a risk, he’ll then consider talking with colleagues in oral or facial surgery. Dr. Tagliati added that the number of patients he sees with oromandibular dystonia is rather small, so this extra step would not add a lot of additional imaging.

Overall, Dr. Tagliati noted that the study outcome was significant enough to want to use it for professional education. “I can definitely tell you that I’m going to bring it to the attention of my Fellows. [Every year] I teach one or two Fellows to inject Botox,” he said.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Yilmaz and Dr. Tagliati have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Oromandibular dystonia causes an involuntary opening of the mouth, which can be disabling and disfiguring. Although injection of the lateral pterygoid muscle with botulinum toxin is the preferred treatment for oromandibular dystonia, a potential complication concerns the maxillary artery, which can run either lateral or medial to the lateral pterygoid muscle.

In a study of 200 Turkish patients, researchers documented significant variations between men and women in the anatomical location of the maxillary artery – and even found lateral versus medial differences on the left and right side in the same individual.

“The results showed that the maxillary artery runs lateral to the muscle in 67% of the Turkish patients,” Rezzak Yilmaz, MD, department of neurology, University of Ankara Medical School, Turkey, reported at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Given this high rate, there is a high risk for injury “that may result in pain and hematoma” when using preauricular extraoral injections, Dr. Yilmaz and colleagues noted. Instead, they recommend an intraoral injection approach to the lateral pterygoid muscle. “However, this critical anatomical variation is still unrecognized by most clinicians performing [botulinum toxin] injections,” they wrote.

Significant gender differences

The maxillary artery is the largest branch of the external carotid artery.

In the current study, the researchers used magnetic resonance angiography to assess the relevant anatomy in a cohort of 200 individuals (mean age, 56.4 years; 64% women) without a history of facial trauma or movement disorders.

Results showed that the maxillary artery ran lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle in 67% of the study population.

“This result was also more frequent in females compared with males. Also, there was a considerable variability between the left and the right side in 20% of the participants,” Dr. Yilmaz reported.

Statistically significant gender differences were found for the artery running lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle on both sides (71.1% in women vs. 58.5% in men; P = .007) and for the artery running lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle on just the left side (69.8% in women vs. 53.5% in men; P = .02).

In an email exchange, Dr. Yilmaz said if medical personnel are not trained to perform an intraoral approach, “imaging to visualize the path of the maxillary artery before an extraoral/transcutaneous injection can be recommended.”

“If the imaging reveals that the maxillary artery passes lateral to the muscle, then the patient needs to be referred to another center for an intraoral injection,” unless the clinician is trained for an intraoral approach, he added.

Useful education

Commenting on the study, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the Movement Disorders Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said the results were educational. “I didn’t know about all this variability. I was working under the assumption that the artery was medial,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

Among his large practice of about 2,000 patients, Dr. Tagliati estimated having five patients for whom he provides this type of injection – and has never encountered a problem with them.

“Maybe all my patients are medial, but now that I’m aware I’ll probably pay more attention,” Dr. Tagliati said. He does not currently perform magnetic resonance angiography before injecting them, “although maybe I should,” he said.

When asked if it is worth the time and expense to perform magnetic resonance angiography on every patient who comes in for lateral pterygoid muscle injections, Dr. Tagliati said that although he has done the injections without problems in his current patients, he may “start obtaining imaging studies to make sure that we’re not taking unnecessary risk” if the maxillary artery is lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle in new patients.

If there is a risk, he’ll then consider talking with colleagues in oral or facial surgery. Dr. Tagliati added that the number of patients he sees with oromandibular dystonia is rather small, so this extra step would not add a lot of additional imaging.

Overall, Dr. Tagliati noted that the study outcome was significant enough to want to use it for professional education. “I can definitely tell you that I’m going to bring it to the attention of my Fellows. [Every year] I teach one or two Fellows to inject Botox,” he said.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Yilmaz and Dr. Tagliati have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Oromandibular dystonia causes an involuntary opening of the mouth, which can be disabling and disfiguring. Although injection of the lateral pterygoid muscle with botulinum toxin is the preferred treatment for oromandibular dystonia, a potential complication concerns the maxillary artery, which can run either lateral or medial to the lateral pterygoid muscle.

In a study of 200 Turkish patients, researchers documented significant variations between men and women in the anatomical location of the maxillary artery – and even found lateral versus medial differences on the left and right side in the same individual.

“The results showed that the maxillary artery runs lateral to the muscle in 67% of the Turkish patients,” Rezzak Yilmaz, MD, department of neurology, University of Ankara Medical School, Turkey, reported at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Given this high rate, there is a high risk for injury “that may result in pain and hematoma” when using preauricular extraoral injections, Dr. Yilmaz and colleagues noted. Instead, they recommend an intraoral injection approach to the lateral pterygoid muscle. “However, this critical anatomical variation is still unrecognized by most clinicians performing [botulinum toxin] injections,” they wrote.

Significant gender differences

The maxillary artery is the largest branch of the external carotid artery.

In the current study, the researchers used magnetic resonance angiography to assess the relevant anatomy in a cohort of 200 individuals (mean age, 56.4 years; 64% women) without a history of facial trauma or movement disorders.

Results showed that the maxillary artery ran lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle in 67% of the study population.

“This result was also more frequent in females compared with males. Also, there was a considerable variability between the left and the right side in 20% of the participants,” Dr. Yilmaz reported.

Statistically significant gender differences were found for the artery running lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle on both sides (71.1% in women vs. 58.5% in men; P = .007) and for the artery running lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle on just the left side (69.8% in women vs. 53.5% in men; P = .02).

In an email exchange, Dr. Yilmaz said if medical personnel are not trained to perform an intraoral approach, “imaging to visualize the path of the maxillary artery before an extraoral/transcutaneous injection can be recommended.”

“If the imaging reveals that the maxillary artery passes lateral to the muscle, then the patient needs to be referred to another center for an intraoral injection,” unless the clinician is trained for an intraoral approach, he added.

Useful education

Commenting on the study, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the Movement Disorders Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said the results were educational. “I didn’t know about all this variability. I was working under the assumption that the artery was medial,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

Among his large practice of about 2,000 patients, Dr. Tagliati estimated having five patients for whom he provides this type of injection – and has never encountered a problem with them.

“Maybe all my patients are medial, but now that I’m aware I’ll probably pay more attention,” Dr. Tagliati said. He does not currently perform magnetic resonance angiography before injecting them, “although maybe I should,” he said.

When asked if it is worth the time and expense to perform magnetic resonance angiography on every patient who comes in for lateral pterygoid muscle injections, Dr. Tagliati said that although he has done the injections without problems in his current patients, he may “start obtaining imaging studies to make sure that we’re not taking unnecessary risk” if the maxillary artery is lateral to the lateral pterygoid muscle in new patients.

If there is a risk, he’ll then consider talking with colleagues in oral or facial surgery. Dr. Tagliati added that the number of patients he sees with oromandibular dystonia is rather small, so this extra step would not add a lot of additional imaging.

Overall, Dr. Tagliati noted that the study outcome was significant enough to want to use it for professional education. “I can definitely tell you that I’m going to bring it to the attention of my Fellows. [Every year] I teach one or two Fellows to inject Botox,” he said.

There was no funding for the study. Dr. Yilmaz and Dr. Tagliati have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Worsening motor function tied to post COVID syndrome in Parkinson’s disease

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Novel drug effective for essential tremor, but with significant side effects

new research suggests.

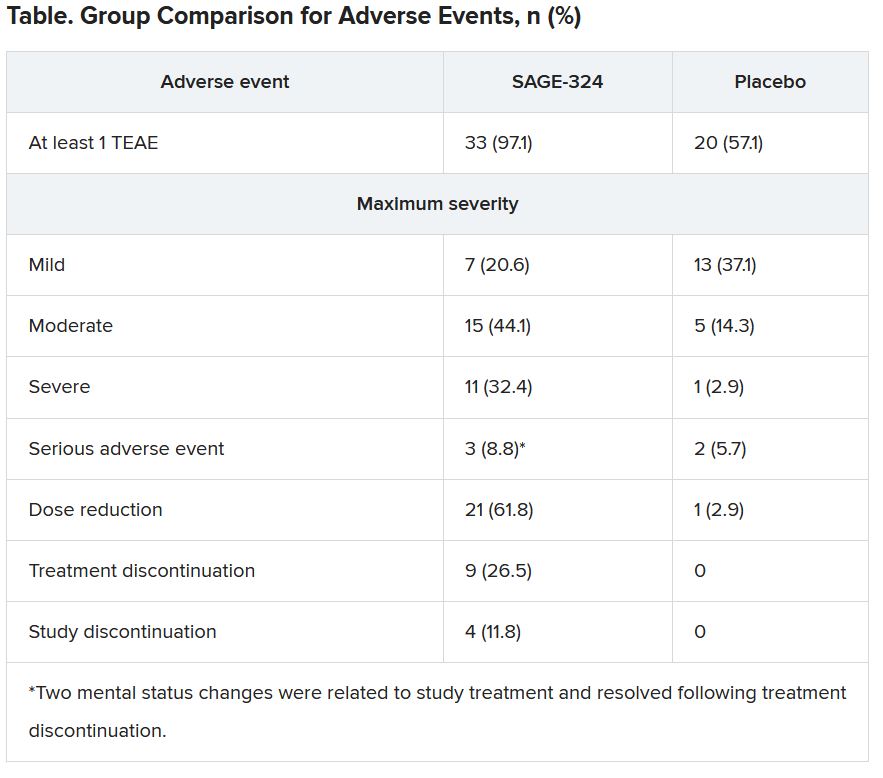

The phase 2 KINETIC trial involved patients with essential tremor. Among patients treated with SAGE-324 for 28 days, there was a statistically significant reduction in upper-limb tremors on day 29 – meeting the primary endpoint of the study.

However, moderate to severe treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) led to many treatment and/or study discontinuations, the investigators reported.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Mechanism of action

Essential tremor affects an estimated 6.4 million adults in the United States. Available drugs are not helpful for 30%-50% of these patients. No new drug for this condition has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the past 50 years. Of the several drugs used to treat essential tremor, propranolol is the only one that has been approved, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Deficits in inhibitory signaling via the gamma-aminobutyric acid system may have a role in the pathophysiology of essential tremor because the GABAergic system is the major neuroinhibitory system in the brain.

SAGE-324 is a steroid-positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. It acts on the receptor distant from the neuronal synapse to enhance GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling.

In the phase 2 multicenter KINETIC trial, investigators enrolled 69 patients aged 18-80 years. The patients had moderate to severe essential tremor, as determined on the basis of their having a score of 10 or higher on item 4 of the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) on screening day and at baseline/day 1 of the trial.

Participants did not take medications for essential tremor during the 28-day washout period. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive SAGE-324 60 mg (n = 34) or placebo (n = 35) once daily. Dose reductions were allowed.

The groups were reasonably matched for age (mean, 69.4 years for SAGE-324 vs. 64.7 years for placebo) and dominant hand (right, 85.3% for SAGE-324 vs. 88.6% for placebo). Women composed 35.3% of the drug group and 57.1% of the placebo group.

The primary endpoint of the trial was change from baseline for the active drug in comparison with placebo on day 29 (1 day after the final dose) for upper-limb tremor, as measured by item 4 of TETRAS. There was also a 2-week follow-up with assessments on day 42.

Primary endpoint met, high dropout rate

Baseline mean TETRAS Performance Subscale item 4 scores were 12.82 for the SAGE-324 group and 12.28 for the placebo group.

On day 29, the least squares mean difference from baseline was –2.31 with SAGE-324 (n = 21) versus –1.24 with placebo (n = 33; P = .049). There was no difference between the SAGE-324 and placebo groups on day 42.

“Their significant reduction in upper-limb tremor score at day 29 corresponds to a 36% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude in patients receiving SAGE-324, compared with a 21% reduction in tremor amplitude in patients receiving a placebo,” said lead investigator Kemi Bankole, MBBCh, of Sage Therapeutics.

“A reduction in tremor amplitude of 36% is a clinically significant improvement for most patients with essential tremor. For patients with moderate-severe tremor, a 41% improvement would be clinically noticeable and appreciated,” said Helen Colquhoun, MBChB, vice president at Sage.

“We believe patients with more severe tremor, that is, a TETRAS score of greater than 12, represent the majority of [essential tremor] patients getting diagnosed and seeking treatment today,” Dr. Colquhoun said.

There was an even greater reduction in tremor amplitude for the subgroup of patients with more severe tremor at baseline, meaning those with a median TETRAS score of 12 or greater (–2.75 for SAGE-324 vs. –1.05 for placebo; P = .0066).

These figures represented a 41% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude for the SAGE-324 group, versus an 18% reduction in the placebo group. Again, the effect had disappeared in comparison with placebo at the 2-week off-drug follow-up on day 42.

Tolerability of SAGE-324 was a major problem, leading to dose reductions, treatment discontinuations, and study discontinuations. Of the 34 patients who received SAGE-324, 13 dropped out of the study, compared with 2 of 35 patients who received placebo.

Most TEAEs were moderate or severe in the SAGE-324 group, whereas most were mild in the placebo group.

The most common TEAEs for participants who received SAGE-324 were somnolence (67.6%) and dizziness (38.2%), followed by balance problems, diplopia, dysarthria, and gait disturbance. In the placebo group, somnolence affected 5.7%, and dizziness affected 11.4%. There were no deaths in either group.

Dr. Colquhoun said these findings “are in line with our expectations for the 60-mg dose.”

More than one-third of the SAGE-324 group discontinued treatment before the end of the trial, and continuing treatment often required dose reductions. Only 24% completed the trial while taking the 60-mg dose; 15% completed the trial while taking 45 mg; and 24% did so while taking 30 mg.

Dr. Colquhoun noted that the company plans to initiate a phase 2b dose-ranging study later this year to optimize the dosing regimen with regard to tolerability and sustained tremor control.

No advantage over older drugs?

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said he had been aware of the study and was interested in seeing the results. However, he does not see an advantage with this drug, compared with what is already used for essential tremor.

“The response of people is not that different than when we treat them with the old barbiturates and benzodiazepines,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

He also noted the high rate of adverse events, particularly somnolence, and said that in his experience with current treatments, some patients prefer to live with their tremors rather than be sleepy and not thinking well.

Dr. Tagliati said he thinks use of SAGE-324 is going to be limited to patients who can tolerate it, “which was not that many.”

In addition, the trial was limited by its relatively small size, a “huge placebo effect,” and a high dropout rate in the active treatment arm, he concluded.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen. Dr. Bankole and Dr. Calquhoun are employees of Sage. Dr. Tagliati reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

The phase 2 KINETIC trial involved patients with essential tremor. Among patients treated with SAGE-324 for 28 days, there was a statistically significant reduction in upper-limb tremors on day 29 – meeting the primary endpoint of the study.

However, moderate to severe treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) led to many treatment and/or study discontinuations, the investigators reported.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Mechanism of action

Essential tremor affects an estimated 6.4 million adults in the United States. Available drugs are not helpful for 30%-50% of these patients. No new drug for this condition has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the past 50 years. Of the several drugs used to treat essential tremor, propranolol is the only one that has been approved, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Deficits in inhibitory signaling via the gamma-aminobutyric acid system may have a role in the pathophysiology of essential tremor because the GABAergic system is the major neuroinhibitory system in the brain.

SAGE-324 is a steroid-positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. It acts on the receptor distant from the neuronal synapse to enhance GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling.

In the phase 2 multicenter KINETIC trial, investigators enrolled 69 patients aged 18-80 years. The patients had moderate to severe essential tremor, as determined on the basis of their having a score of 10 or higher on item 4 of the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) on screening day and at baseline/day 1 of the trial.

Participants did not take medications for essential tremor during the 28-day washout period. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive SAGE-324 60 mg (n = 34) or placebo (n = 35) once daily. Dose reductions were allowed.

The groups were reasonably matched for age (mean, 69.4 years for SAGE-324 vs. 64.7 years for placebo) and dominant hand (right, 85.3% for SAGE-324 vs. 88.6% for placebo). Women composed 35.3% of the drug group and 57.1% of the placebo group.

The primary endpoint of the trial was change from baseline for the active drug in comparison with placebo on day 29 (1 day after the final dose) for upper-limb tremor, as measured by item 4 of TETRAS. There was also a 2-week follow-up with assessments on day 42.

Primary endpoint met, high dropout rate

Baseline mean TETRAS Performance Subscale item 4 scores were 12.82 for the SAGE-324 group and 12.28 for the placebo group.

On day 29, the least squares mean difference from baseline was –2.31 with SAGE-324 (n = 21) versus –1.24 with placebo (n = 33; P = .049). There was no difference between the SAGE-324 and placebo groups on day 42.

“Their significant reduction in upper-limb tremor score at day 29 corresponds to a 36% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude in patients receiving SAGE-324, compared with a 21% reduction in tremor amplitude in patients receiving a placebo,” said lead investigator Kemi Bankole, MBBCh, of Sage Therapeutics.

“A reduction in tremor amplitude of 36% is a clinically significant improvement for most patients with essential tremor. For patients with moderate-severe tremor, a 41% improvement would be clinically noticeable and appreciated,” said Helen Colquhoun, MBChB, vice president at Sage.

“We believe patients with more severe tremor, that is, a TETRAS score of greater than 12, represent the majority of [essential tremor] patients getting diagnosed and seeking treatment today,” Dr. Colquhoun said.

There was an even greater reduction in tremor amplitude for the subgroup of patients with more severe tremor at baseline, meaning those with a median TETRAS score of 12 or greater (–2.75 for SAGE-324 vs. –1.05 for placebo; P = .0066).

These figures represented a 41% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude for the SAGE-324 group, versus an 18% reduction in the placebo group. Again, the effect had disappeared in comparison with placebo at the 2-week off-drug follow-up on day 42.

Tolerability of SAGE-324 was a major problem, leading to dose reductions, treatment discontinuations, and study discontinuations. Of the 34 patients who received SAGE-324, 13 dropped out of the study, compared with 2 of 35 patients who received placebo.

Most TEAEs were moderate or severe in the SAGE-324 group, whereas most were mild in the placebo group.

The most common TEAEs for participants who received SAGE-324 were somnolence (67.6%) and dizziness (38.2%), followed by balance problems, diplopia, dysarthria, and gait disturbance. In the placebo group, somnolence affected 5.7%, and dizziness affected 11.4%. There were no deaths in either group.

Dr. Colquhoun said these findings “are in line with our expectations for the 60-mg dose.”

More than one-third of the SAGE-324 group discontinued treatment before the end of the trial, and continuing treatment often required dose reductions. Only 24% completed the trial while taking the 60-mg dose; 15% completed the trial while taking 45 mg; and 24% did so while taking 30 mg.

Dr. Colquhoun noted that the company plans to initiate a phase 2b dose-ranging study later this year to optimize the dosing regimen with regard to tolerability and sustained tremor control.

No advantage over older drugs?

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said he had been aware of the study and was interested in seeing the results. However, he does not see an advantage with this drug, compared with what is already used for essential tremor.

“The response of people is not that different than when we treat them with the old barbiturates and benzodiazepines,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

He also noted the high rate of adverse events, particularly somnolence, and said that in his experience with current treatments, some patients prefer to live with their tremors rather than be sleepy and not thinking well.

Dr. Tagliati said he thinks use of SAGE-324 is going to be limited to patients who can tolerate it, “which was not that many.”

In addition, the trial was limited by its relatively small size, a “huge placebo effect,” and a high dropout rate in the active treatment arm, he concluded.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen. Dr. Bankole and Dr. Calquhoun are employees of Sage. Dr. Tagliati reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

The phase 2 KINETIC trial involved patients with essential tremor. Among patients treated with SAGE-324 for 28 days, there was a statistically significant reduction in upper-limb tremors on day 29 – meeting the primary endpoint of the study.

However, moderate to severe treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) led to many treatment and/or study discontinuations, the investigators reported.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Mechanism of action

Essential tremor affects an estimated 6.4 million adults in the United States. Available drugs are not helpful for 30%-50% of these patients. No new drug for this condition has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the past 50 years. Of the several drugs used to treat essential tremor, propranolol is the only one that has been approved, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Deficits in inhibitory signaling via the gamma-aminobutyric acid system may have a role in the pathophysiology of essential tremor because the GABAergic system is the major neuroinhibitory system in the brain.

SAGE-324 is a steroid-positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. It acts on the receptor distant from the neuronal synapse to enhance GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling.

In the phase 2 multicenter KINETIC trial, investigators enrolled 69 patients aged 18-80 years. The patients had moderate to severe essential tremor, as determined on the basis of their having a score of 10 or higher on item 4 of the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) on screening day and at baseline/day 1 of the trial.

Participants did not take medications for essential tremor during the 28-day washout period. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive SAGE-324 60 mg (n = 34) or placebo (n = 35) once daily. Dose reductions were allowed.

The groups were reasonably matched for age (mean, 69.4 years for SAGE-324 vs. 64.7 years for placebo) and dominant hand (right, 85.3% for SAGE-324 vs. 88.6% for placebo). Women composed 35.3% of the drug group and 57.1% of the placebo group.

The primary endpoint of the trial was change from baseline for the active drug in comparison with placebo on day 29 (1 day after the final dose) for upper-limb tremor, as measured by item 4 of TETRAS. There was also a 2-week follow-up with assessments on day 42.

Primary endpoint met, high dropout rate

Baseline mean TETRAS Performance Subscale item 4 scores were 12.82 for the SAGE-324 group and 12.28 for the placebo group.

On day 29, the least squares mean difference from baseline was –2.31 with SAGE-324 (n = 21) versus –1.24 with placebo (n = 33; P = .049). There was no difference between the SAGE-324 and placebo groups on day 42.

“Their significant reduction in upper-limb tremor score at day 29 corresponds to a 36% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude in patients receiving SAGE-324, compared with a 21% reduction in tremor amplitude in patients receiving a placebo,” said lead investigator Kemi Bankole, MBBCh, of Sage Therapeutics.

“A reduction in tremor amplitude of 36% is a clinically significant improvement for most patients with essential tremor. For patients with moderate-severe tremor, a 41% improvement would be clinically noticeable and appreciated,” said Helen Colquhoun, MBChB, vice president at Sage.

“We believe patients with more severe tremor, that is, a TETRAS score of greater than 12, represent the majority of [essential tremor] patients getting diagnosed and seeking treatment today,” Dr. Colquhoun said.

There was an even greater reduction in tremor amplitude for the subgroup of patients with more severe tremor at baseline, meaning those with a median TETRAS score of 12 or greater (–2.75 for SAGE-324 vs. –1.05 for placebo; P = .0066).

These figures represented a 41% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude for the SAGE-324 group, versus an 18% reduction in the placebo group. Again, the effect had disappeared in comparison with placebo at the 2-week off-drug follow-up on day 42.

Tolerability of SAGE-324 was a major problem, leading to dose reductions, treatment discontinuations, and study discontinuations. Of the 34 patients who received SAGE-324, 13 dropped out of the study, compared with 2 of 35 patients who received placebo.

Most TEAEs were moderate or severe in the SAGE-324 group, whereas most were mild in the placebo group.

The most common TEAEs for participants who received SAGE-324 were somnolence (67.6%) and dizziness (38.2%), followed by balance problems, diplopia, dysarthria, and gait disturbance. In the placebo group, somnolence affected 5.7%, and dizziness affected 11.4%. There were no deaths in either group.

Dr. Colquhoun said these findings “are in line with our expectations for the 60-mg dose.”

More than one-third of the SAGE-324 group discontinued treatment before the end of the trial, and continuing treatment often required dose reductions. Only 24% completed the trial while taking the 60-mg dose; 15% completed the trial while taking 45 mg; and 24% did so while taking 30 mg.

Dr. Colquhoun noted that the company plans to initiate a phase 2b dose-ranging study later this year to optimize the dosing regimen with regard to tolerability and sustained tremor control.

No advantage over older drugs?

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said he had been aware of the study and was interested in seeing the results. However, he does not see an advantage with this drug, compared with what is already used for essential tremor.

“The response of people is not that different than when we treat them with the old barbiturates and benzodiazepines,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

He also noted the high rate of adverse events, particularly somnolence, and said that in his experience with current treatments, some patients prefer to live with their tremors rather than be sleepy and not thinking well.

Dr. Tagliati said he thinks use of SAGE-324 is going to be limited to patients who can tolerate it, “which was not that many.”

In addition, the trial was limited by its relatively small size, a “huge placebo effect,” and a high dropout rate in the active treatment arm, he concluded.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen. Dr. Bankole and Dr. Calquhoun are employees of Sage. Dr. Tagliati reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Apple devices identify early Parkinson’s disease

, new research shows. Results from the WATCH-PD study show clear differences in a finger-tapping task in the Parkinson’s disease versus control group. The finger-tapping task also correlated with “traditional measures,” such as the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), investigators reported.

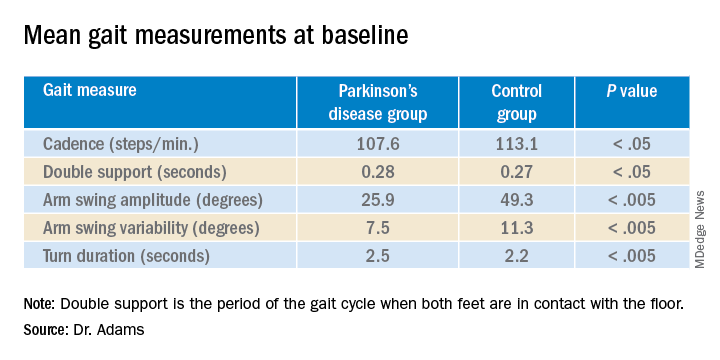

“And then the smartphone and smartwatch also showed differences in gait between groups,” said lead investigator Jamie Adams, MD, University of Rochester, New York.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

WATCH-PD

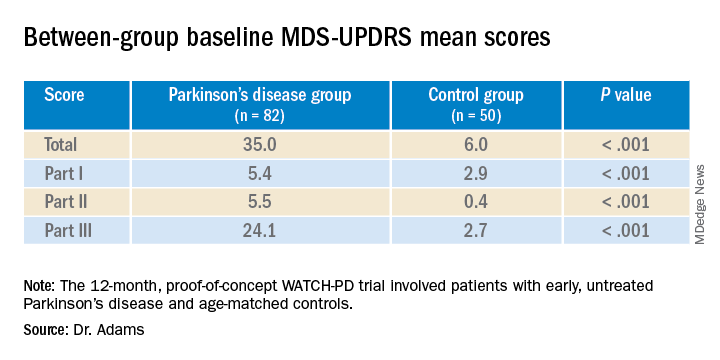

The 12-month WATCH-PD study included 132 individuals at 17 Parkinson’s Study Group sites, 82 with Parkinson’s disease and 50 controls.

Participants with Parkinson’s disease were untreated, were no more than 2 years out from diagnosis (mean disease duration, 10.0 ±7.3 months), and were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 or 2.

Apple Watches and iPhones were provided to participants, all of whom underwent in-clinic assessments at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The assessments included motor and cognitive tasks using the devices, which contained motion sensors.

The phone also contained an app that could assess verbal, cognitive, and other abilities. Participants wore a set of inertial sensors (APDM Mobility Lab) while performing the MDS-UPDRS Part III motor examination.

In addition, there were biweekly at-home tasks. Questions and tests on the watch assessed symptoms of mood, fatigue, cognition, and falls as well as cognitive performance involving perceptual, verbal, visual spatial, and fine motor abilities. Both the watch and iPhone were used to gauge gait, balance, and tremor.

Ages of the participants were approximately the same in the Parkinson’s disease and control groups (63.3 years vs. 60.2 years, respectively), but male to female ratios differed between the groups. There were more men in the Parkinson’s disease cohort (56% men vs. 44% women) and more women in the control cohort (36% vs. 64%; P =.03).

Between-group differences

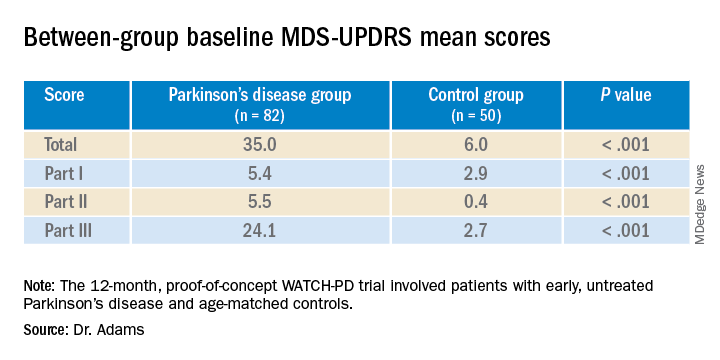

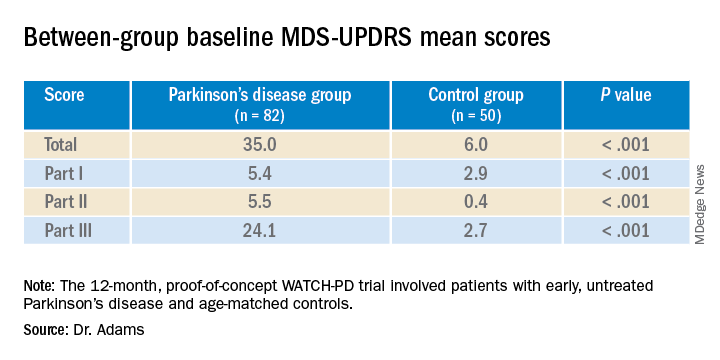

Results showed that MDS-UPDRS total scores and on all individual parts of the rating scale were significantly better for the control group (lower scores are better), as shown in the following table.

Similarly, the control group performed better than the Parkinson’s disease group on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with higher scores showing better performance on the 0 to 30 scale (28.1 vs. 27.6, respectively).

Touchscreen assessments on the phone also showed group differences in a finger-tapping task, with more taps by the control group than by the Parkinson’s disease group. The difference was more pronounced when the dominant hand was used.

The median numbers of taps in 20 seconds for the dominant hand were 103.7 for the Parkinson’s disease cohort versus 131.9 for control cohort (P < .005); and for the nondominant hand the numbers of taps were 106.6 versus 122.1 (P < .05), respectively. The control group also scored better on tests of hand fine-motor control (P < .01) and on the mobile digit symbols modalities test (P < .05)

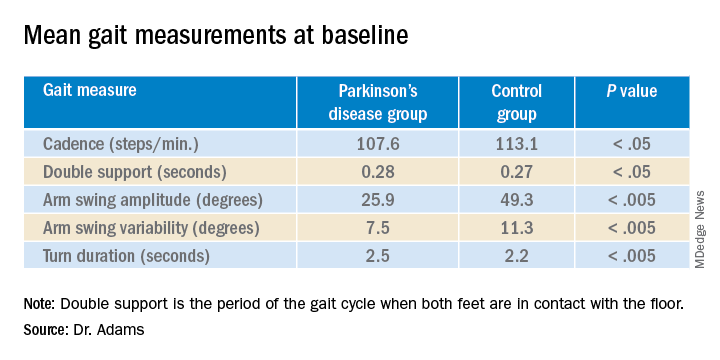

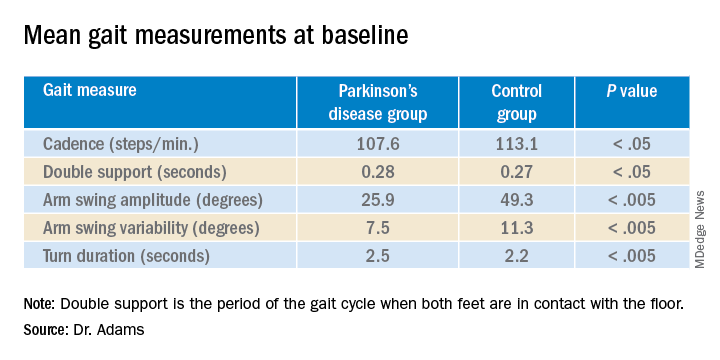

Measures of gait in a 1-minute walk test also showed group differences.

“The five gait measures that differed most were cadence, which is steps per minute, double support, arm swing amplitude, arm swing variation, and turn duration,” Dr. Adams said.

‘Tremendous interest’

Commenting on the findings, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, of Boston University, noted that in the future, devices such as the ones used in this study may help clinicians remotely monitor their patients’ Parkinson’s disease conditions and response to therapy.

That would “eliminate some of the transportation barrier for people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Shih, who was not involved with the research.

The devices can give objective measurements, reducing inter-rater variability in assessment of movements, she noted.

“I think there’s tremendous interest in using digital measures to pick up on subtle disease phenotypes earlier than a clinical diagnosis can be made,” Dr. Shih said.

She also referred to literature “going back a few decades” showing that finger tapping can be used as a pharmacodynamic measure of how well a patient’s dopaminergic medications are working, so the devices may be a way to remotely assess treatment efficacy and decide when it is time to make adjustments.

Dr. Shih said she thinks regulatory agencies are now open “to consider these as part of the totality of evidence that a therapeutic [device] might be working.”

Whether these would need to be professional grade and approved as medical devices or if patients could just buy smartwatches and smartphones to generate useful data is still a question, she said. Already, there are several Parkinson’s apps that the public can download to track symptoms, improve voice, provide exercises, find support groups or research studies, and more.

Dr. Shih predicted that the biweekly at-home tasks, as in the current protocol, could be a burden to some people. If only a segment of the population were willing to comply, it could call into question how generalizable the results were, she added.

“There’s even a prior publication showing that compliance rate really dropped like a rock,” she noted. However, for those people willing to perform the tasks on a regular schedule, the results could be valuable, Dr. Shih said.

Dr. Adams concurred, saying that she had received feedback from some of her study participants that the biweekly tasks were a bit much.

The study was supported by Biogen and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Adams receives research support from Biogen. Dr. Shih has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results from the WATCH-PD study show clear differences in a finger-tapping task in the Parkinson’s disease versus control group. The finger-tapping task also correlated with “traditional measures,” such as the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), investigators reported.

“And then the smartphone and smartwatch also showed differences in gait between groups,” said lead investigator Jamie Adams, MD, University of Rochester, New York.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

WATCH-PD

The 12-month WATCH-PD study included 132 individuals at 17 Parkinson’s Study Group sites, 82 with Parkinson’s disease and 50 controls.

Participants with Parkinson’s disease were untreated, were no more than 2 years out from diagnosis (mean disease duration, 10.0 ±7.3 months), and were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 or 2.

Apple Watches and iPhones were provided to participants, all of whom underwent in-clinic assessments at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The assessments included motor and cognitive tasks using the devices, which contained motion sensors.

The phone also contained an app that could assess verbal, cognitive, and other abilities. Participants wore a set of inertial sensors (APDM Mobility Lab) while performing the MDS-UPDRS Part III motor examination.

In addition, there were biweekly at-home tasks. Questions and tests on the watch assessed symptoms of mood, fatigue, cognition, and falls as well as cognitive performance involving perceptual, verbal, visual spatial, and fine motor abilities. Both the watch and iPhone were used to gauge gait, balance, and tremor.

Ages of the participants were approximately the same in the Parkinson’s disease and control groups (63.3 years vs. 60.2 years, respectively), but male to female ratios differed between the groups. There were more men in the Parkinson’s disease cohort (56% men vs. 44% women) and more women in the control cohort (36% vs. 64%; P =.03).

Between-group differences

Results showed that MDS-UPDRS total scores and on all individual parts of the rating scale were significantly better for the control group (lower scores are better), as shown in the following table.

Similarly, the control group performed better than the Parkinson’s disease group on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with higher scores showing better performance on the 0 to 30 scale (28.1 vs. 27.6, respectively).

Touchscreen assessments on the phone also showed group differences in a finger-tapping task, with more taps by the control group than by the Parkinson’s disease group. The difference was more pronounced when the dominant hand was used.

The median numbers of taps in 20 seconds for the dominant hand were 103.7 for the Parkinson’s disease cohort versus 131.9 for control cohort (P < .005); and for the nondominant hand the numbers of taps were 106.6 versus 122.1 (P < .05), respectively. The control group also scored better on tests of hand fine-motor control (P < .01) and on the mobile digit symbols modalities test (P < .05)

Measures of gait in a 1-minute walk test also showed group differences.

“The five gait measures that differed most were cadence, which is steps per minute, double support, arm swing amplitude, arm swing variation, and turn duration,” Dr. Adams said.

‘Tremendous interest’

Commenting on the findings, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, of Boston University, noted that in the future, devices such as the ones used in this study may help clinicians remotely monitor their patients’ Parkinson’s disease conditions and response to therapy.

That would “eliminate some of the transportation barrier for people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Shih, who was not involved with the research.

The devices can give objective measurements, reducing inter-rater variability in assessment of movements, she noted.

“I think there’s tremendous interest in using digital measures to pick up on subtle disease phenotypes earlier than a clinical diagnosis can be made,” Dr. Shih said.

She also referred to literature “going back a few decades” showing that finger tapping can be used as a pharmacodynamic measure of how well a patient’s dopaminergic medications are working, so the devices may be a way to remotely assess treatment efficacy and decide when it is time to make adjustments.

Dr. Shih said she thinks regulatory agencies are now open “to consider these as part of the totality of evidence that a therapeutic [device] might be working.”

Whether these would need to be professional grade and approved as medical devices or if patients could just buy smartwatches and smartphones to generate useful data is still a question, she said. Already, there are several Parkinson’s apps that the public can download to track symptoms, improve voice, provide exercises, find support groups or research studies, and more.

Dr. Shih predicted that the biweekly at-home tasks, as in the current protocol, could be a burden to some people. If only a segment of the population were willing to comply, it could call into question how generalizable the results were, she added.

“There’s even a prior publication showing that compliance rate really dropped like a rock,” she noted. However, for those people willing to perform the tasks on a regular schedule, the results could be valuable, Dr. Shih said.

Dr. Adams concurred, saying that she had received feedback from some of her study participants that the biweekly tasks were a bit much.

The study was supported by Biogen and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Adams receives research support from Biogen. Dr. Shih has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results from the WATCH-PD study show clear differences in a finger-tapping task in the Parkinson’s disease versus control group. The finger-tapping task also correlated with “traditional measures,” such as the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), investigators reported.

“And then the smartphone and smartwatch also showed differences in gait between groups,” said lead investigator Jamie Adams, MD, University of Rochester, New York.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

WATCH-PD

The 12-month WATCH-PD study included 132 individuals at 17 Parkinson’s Study Group sites, 82 with Parkinson’s disease and 50 controls.

Participants with Parkinson’s disease were untreated, were no more than 2 years out from diagnosis (mean disease duration, 10.0 ±7.3 months), and were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 or 2.

Apple Watches and iPhones were provided to participants, all of whom underwent in-clinic assessments at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The assessments included motor and cognitive tasks using the devices, which contained motion sensors.

The phone also contained an app that could assess verbal, cognitive, and other abilities. Participants wore a set of inertial sensors (APDM Mobility Lab) while performing the MDS-UPDRS Part III motor examination.

In addition, there were biweekly at-home tasks. Questions and tests on the watch assessed symptoms of mood, fatigue, cognition, and falls as well as cognitive performance involving perceptual, verbal, visual spatial, and fine motor abilities. Both the watch and iPhone were used to gauge gait, balance, and tremor.

Ages of the participants were approximately the same in the Parkinson’s disease and control groups (63.3 years vs. 60.2 years, respectively), but male to female ratios differed between the groups. There were more men in the Parkinson’s disease cohort (56% men vs. 44% women) and more women in the control cohort (36% vs. 64%; P =.03).

Between-group differences

Results showed that MDS-UPDRS total scores and on all individual parts of the rating scale were significantly better for the control group (lower scores are better), as shown in the following table.

Similarly, the control group performed better than the Parkinson’s disease group on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with higher scores showing better performance on the 0 to 30 scale (28.1 vs. 27.6, respectively).

Touchscreen assessments on the phone also showed group differences in a finger-tapping task, with more taps by the control group than by the Parkinson’s disease group. The difference was more pronounced when the dominant hand was used.

The median numbers of taps in 20 seconds for the dominant hand were 103.7 for the Parkinson’s disease cohort versus 131.9 for control cohort (P < .005); and for the nondominant hand the numbers of taps were 106.6 versus 122.1 (P < .05), respectively. The control group also scored better on tests of hand fine-motor control (P < .01) and on the mobile digit symbols modalities test (P < .05)

Measures of gait in a 1-minute walk test also showed group differences.

“The five gait measures that differed most were cadence, which is steps per minute, double support, arm swing amplitude, arm swing variation, and turn duration,” Dr. Adams said.

‘Tremendous interest’

Commenting on the findings, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, of Boston University, noted that in the future, devices such as the ones used in this study may help clinicians remotely monitor their patients’ Parkinson’s disease conditions and response to therapy.

That would “eliminate some of the transportation barrier for people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Shih, who was not involved with the research.

The devices can give objective measurements, reducing inter-rater variability in assessment of movements, she noted.

“I think there’s tremendous interest in using digital measures to pick up on subtle disease phenotypes earlier than a clinical diagnosis can be made,” Dr. Shih said.

She also referred to literature “going back a few decades” showing that finger tapping can be used as a pharmacodynamic measure of how well a patient’s dopaminergic medications are working, so the devices may be a way to remotely assess treatment efficacy and decide when it is time to make adjustments.

Dr. Shih said she thinks regulatory agencies are now open “to consider these as part of the totality of evidence that a therapeutic [device] might be working.”

Whether these would need to be professional grade and approved as medical devices or if patients could just buy smartwatches and smartphones to generate useful data is still a question, she said. Already, there are several Parkinson’s apps that the public can download to track symptoms, improve voice, provide exercises, find support groups or research studies, and more.

Dr. Shih predicted that the biweekly at-home tasks, as in the current protocol, could be a burden to some people. If only a segment of the population were willing to comply, it could call into question how generalizable the results were, she added.

“There’s even a prior publication showing that compliance rate really dropped like a rock,” she noted. However, for those people willing to perform the tasks on a regular schedule, the results could be valuable, Dr. Shih said.

Dr. Adams concurred, saying that she had received feedback from some of her study participants that the biweekly tasks were a bit much.

The study was supported by Biogen and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Adams receives research support from Biogen. Dr. Shih has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Study identifies pandemic-related stressor in Parkinson’s disease

a team of researchers in the Netherlands reported, but they also identified meaningful targets for intervention.

Lisanne Dommershuijsen, MSc, a PhD candidate and researcher in epidemiology at the Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, reported on a cross-sectional study of 833 participants with Parkinson’s disease in the PRIME-NL study at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. The average age of participants was 70.2 and 38% were women.

“We studied targeted hypothetical interventions on COVID-19 stressors in people with Parkinson’s disease,” Ms. Dommershuijsen said. “This disruption in normal life caused considerable psychological stress in community-dwelling individuals. People with Parkinson’s disease might be especially vulnerable to this stress.

“For instance, because reduced levels of physical activity have worsened symptoms or because people with Parkinson’s often have difficulty with flexible [adaptations] to drastic and rapid changes in daily routines, such as those introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic, previous studies found that COVID-19 worsened depression and anxiety symptoms and reduced quality of life (QOL) in people with Parkinson’s disease,” Ms. Dommershuijsen said.

Hence, the goal of the study was to identify the most vulnerable subgroups in the Parkinson’s population and to suggest potential interventions to ameliorate these impacts, she said.

The study focused on eight different stressors that emerged in the pandemic: access to care, medicine and nursing services; loss of social contact; canceled social events; tension or conflict in the home; inability to perform physical activity or relax; and COVID-19 symptoms. The outcomes of interest were depression, as measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); anxiety, as measured with the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI); and QOL, with the Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire. The aggregate resulted in a scale of 0-40, with the mean stressor score in the study being 9.6, Ms. Dommershuijsen said.

The BDI and STAI scores for social stressors – loss of social contacts, social events canceled and tension or conflict at home – exceeded those for the so-called care stressors – problems accessing care, medication or nursing – she said, although all eight stressors yielded higher BDI and STAI scores across the board.

Vulnerable subgroups

“When we looked at vulnerable subgroups of people with Parkinson’s disease, we found more pronounced associations between the COVID-19 stress and mental health in women, in highly educated participants, and in participants with advanced Parkinson’s disease,” Ms. Dommershuijsen said. The impact on women and people with advanced disease is explainable, Ms. Dommershuijsen added in an interview; the former because depressive symptoms are more common in women, and the latter because loss of access to care impacts mental wellness.

“The finding that social stressors were more related to anxiety in highly educated people was surprising to us, given that depression in general is more common in people with a lower education,” she said in an interview. “One previous study of the general population suggested this might be related to expectations about available resources, but this findings and the possible explanation warrants further investigation.”

When the study stratified for coping strategies, the COVID-19 stressors had a smaller effect on depressive and anxiety symptoms in Parkinson’s disease patients prone to confrontive coping and planful problem solving, she said. “Whereas, we observed a larger effect of these stressors in people who are prone to using distancing or seeking social support as coping mechanisms,” Ms. Dommershuijsen said.

The researchers also created a model of a hypothetical 50% reduction in COVID-19 stressors among all study participants, but the effect wasn’t clinically relevant, Ms. Dommershuijsen said. However, in people with advanced Parkinson’s disease – that is, with an Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale score above median – the effect was clinically relevant in all outcomes.

The potential interventions the study identified were telemedicine via virtual consultations to alleviate care stressors, and virtual support groups and online classes to address social stressors. “However, a more personalized approach is needed to target tension or conflict at home, which was the most important social stressor influencing depression and anxiety symptoms in our study,” she said. “Social work can play an important role here.”

Asked to comment on the study, Roy Alcalay, MD, professor of neurology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, said in an interview that the findings align with his research on the impact of COVID-19 and related restrictions on people with Parkinson’s disease.

“The pandemic has affected people in different ways,” he said. “Initially very acutely, people just didn’t have access to doctors. There was also the acute question in movement disorders, but also in other diseases where the people with Parkinson’s disease are going to have the worse outcome when they have COVID-19.” Dr. Alcalay authored two recent papers on the impact of COVID-19 in people with Parkinson’s disease.

“Then we see that, in addition to that question, there’s the question of even if they don’t have COVID-19, just the social distancing and the lack of access to health care, and specifically to physical and occupational therapy and other services, can be quite damaging,” he said.

What’s commendable about the study, he said, was that it just doesn’t highlight the problem. “They’re also highlighting potential solutions, that planful problem solving and coping strategies can be helpful to people.”

Neither Ms. Dommershuijsen nor Dr. Alcalay have any relevant relationships to disclose.

a team of researchers in the Netherlands reported, but they also identified meaningful targets for intervention.

Lisanne Dommershuijsen, MSc, a PhD candidate and researcher in epidemiology at the Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, reported on a cross-sectional study of 833 participants with Parkinson’s disease in the PRIME-NL study at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. The average age of participants was 70.2 and 38% were women.

“We studied targeted hypothetical interventions on COVID-19 stressors in people with Parkinson’s disease,” Ms. Dommershuijsen said. “This disruption in normal life caused considerable psychological stress in community-dwelling individuals. People with Parkinson’s disease might be especially vulnerable to this stress.

“For instance, because reduced levels of physical activity have worsened symptoms or because people with Parkinson’s often have difficulty with flexible [adaptations] to drastic and rapid changes in daily routines, such as those introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic, previous studies found that COVID-19 worsened depression and anxiety symptoms and reduced quality of life (QOL) in people with Parkinson’s disease,” Ms. Dommershuijsen said.

Hence, the goal of the study was to identify the most vulnerable subgroups in the Parkinson’s population and to suggest potential interventions to ameliorate these impacts, she said.

The study focused on eight different stressors that emerged in the pandemic: access to care, medicine and nursing services; loss of social contact; canceled social events; tension or conflict in the home; inability to perform physical activity or relax; and COVID-19 symptoms. The outcomes of interest were depression, as measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); anxiety, as measured with the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI); and QOL, with the Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire. The aggregate resulted in a scale of 0-40, with the mean stressor score in the study being 9.6, Ms. Dommershuijsen said.

The BDI and STAI scores for social stressors – loss of social contacts, social events canceled and tension or conflict at home – exceeded those for the so-called care stressors – problems accessing care, medication or nursing – she said, although all eight stressors yielded higher BDI and STAI scores across the board.

Vulnerable subgroups

“When we looked at vulnerable subgroups of people with Parkinson’s disease, we found more pronounced associations between the COVID-19 stress and mental health in women, in highly educated participants, and in participants with advanced Parkinson’s disease,” Ms. Dommershuijsen said. The impact on women and people with advanced disease is explainable, Ms. Dommershuijsen added in an interview; the former because depressive symptoms are more common in women, and the latter because loss of access to care impacts mental wellness.

“The finding that social stressors were more related to anxiety in highly educated people was surprising to us, given that depression in general is more common in people with a lower education,” she said in an interview. “One previous study of the general population suggested this might be related to expectations about available resources, but this findings and the possible explanation warrants further investigation.”