User login

Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD): Annual Meeting

What should PCPs know about pediatric dermatology?

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Thought leaders in pediatrics, family practice medicine, and pediatric dermatology all agree: Primary care providers need to know more – a lot more – about pediatric skin conditions.

A 20-member expert committee drawn from these disciplines has reached consensus on a lengthy wish list of educational objectives. The committee members scrutinized 235 proposed objectives in 16 content areas of pediatric dermatology. Their task was to rate the importance of each of these objectives for resident physicians who plan to see children in their general practice of primary ambulatory care or urgent care.

Ultimately 72% of the items were approved by the panel, which used the Delphi method of achieving consensus, Dr. Erin Mathes reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

It’s a successful initial step in the long-term goal of creating an online pediatric dermatology curriculum for primary care providers. Such a tool is badly needed because primary care physicians, not dermatologists, see most children with skin disease. By some estimates, skin complaints account for up to 30% of all primary care and emergency department visits. Moreover, primary care physicians rate their access to pediatric dermatologists as the third worst of all pediatric subspecialties, behind only child psychiatry and developmental and behavioral pediatrics.

Education in dermatology in medical school is quite limited. At the University of California, San Francisco, for example, where Dr. Mathes serves on the pediatric dermatology faculty, medical students receive a grand total of 7 hours of dermatologic education.

To help with this unmet need, the American Academy of Dermatology has created its online basic dermatology curriculum for self-directed learning. It has been a big hit with primary care providers and trainees. In 2013, the website received 317,000 page views, and 18% of the visitors to the site were international.

"But the AAD site lacks important pediatric dermatology content and is not particularly sophisticated in certain areas. There is a lot of room for improvement, and we can help out," Dr. Mathes explained by way of background to the SPD-supported curriculum development project.

Items that made the panel’s final cut generally fell into two broad categories: diagnosis and management of common conditions such as acne, warts, atopic dermatitis, reactive erythemas, and viral and bacterial skin disease; and recognition, triage, and appropriate referral of more rare or dangerous conditions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, vasculitis, and drug reactions.

What did not make the list were benign conditions such as lichen striatus, cysts, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and nail disorders. "A lot of the lumps and bumps weren’t deemed important," said Dr. Mathes.

Also shot down was education regarding inherited conditions, with two notable exceptions: neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis. Ichthyosis and epidermolysis bullosa were not considered to be important.

A specialty-based split emerged regarding the perceived importance of learning to perform fungal cultures and other office-based diagnostic tests. The pediatricians on the expert panel felt for the most part that they shouldn’t ask pediatric residents to know how to do them, while the family physicians and pediatric dermatologists rated that as clinically important information.

The next step will be to create educational modules to address the approved educational objectives. The modules will then be evaluated in test runs involving medical residents at collaborating institutions. Partnerships are being pursued with major medical societies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the physician assistant organizations.

Several audience members at the SPD meeting rose to complain that some of the panel’s recommendations just don’t seem to make sense.

"It seems like, for example, primary care providers need to understand at least the basics of the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis or they’ll never stop referring patients to us, they’ll never understand why we treat it the way we do, and they’ll never be able to take ownership of atopic dermatitis in some small way. It seems glaringly obvious," one pediatric dermatologist asserted.

Dr. Mathes replied: "You have a very expert opinion on this. It’s what many pediatric dermatologists would think," she said. "The pediatricians and family physicians feel differently. They would counter, ‘I do not have time to know the pathophysiology of all these things.’ They have a lot of other stuff they need to know. They have to know about the heart, the lungs, about normal development – all sorts of stuff. They have just too much to know."

The educational objectives consensus project was funded by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Dr. Mathes reported having no financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Thought leaders in pediatrics, family practice medicine, and pediatric dermatology all agree: Primary care providers need to know more – a lot more – about pediatric skin conditions.

A 20-member expert committee drawn from these disciplines has reached consensus on a lengthy wish list of educational objectives. The committee members scrutinized 235 proposed objectives in 16 content areas of pediatric dermatology. Their task was to rate the importance of each of these objectives for resident physicians who plan to see children in their general practice of primary ambulatory care or urgent care.

Ultimately 72% of the items were approved by the panel, which used the Delphi method of achieving consensus, Dr. Erin Mathes reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

It’s a successful initial step in the long-term goal of creating an online pediatric dermatology curriculum for primary care providers. Such a tool is badly needed because primary care physicians, not dermatologists, see most children with skin disease. By some estimates, skin complaints account for up to 30% of all primary care and emergency department visits. Moreover, primary care physicians rate their access to pediatric dermatologists as the third worst of all pediatric subspecialties, behind only child psychiatry and developmental and behavioral pediatrics.

Education in dermatology in medical school is quite limited. At the University of California, San Francisco, for example, where Dr. Mathes serves on the pediatric dermatology faculty, medical students receive a grand total of 7 hours of dermatologic education.

To help with this unmet need, the American Academy of Dermatology has created its online basic dermatology curriculum for self-directed learning. It has been a big hit with primary care providers and trainees. In 2013, the website received 317,000 page views, and 18% of the visitors to the site were international.

"But the AAD site lacks important pediatric dermatology content and is not particularly sophisticated in certain areas. There is a lot of room for improvement, and we can help out," Dr. Mathes explained by way of background to the SPD-supported curriculum development project.

Items that made the panel’s final cut generally fell into two broad categories: diagnosis and management of common conditions such as acne, warts, atopic dermatitis, reactive erythemas, and viral and bacterial skin disease; and recognition, triage, and appropriate referral of more rare or dangerous conditions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, vasculitis, and drug reactions.

What did not make the list were benign conditions such as lichen striatus, cysts, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and nail disorders. "A lot of the lumps and bumps weren’t deemed important," said Dr. Mathes.

Also shot down was education regarding inherited conditions, with two notable exceptions: neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis. Ichthyosis and epidermolysis bullosa were not considered to be important.

A specialty-based split emerged regarding the perceived importance of learning to perform fungal cultures and other office-based diagnostic tests. The pediatricians on the expert panel felt for the most part that they shouldn’t ask pediatric residents to know how to do them, while the family physicians and pediatric dermatologists rated that as clinically important information.

The next step will be to create educational modules to address the approved educational objectives. The modules will then be evaluated in test runs involving medical residents at collaborating institutions. Partnerships are being pursued with major medical societies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the physician assistant organizations.

Several audience members at the SPD meeting rose to complain that some of the panel’s recommendations just don’t seem to make sense.

"It seems like, for example, primary care providers need to understand at least the basics of the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis or they’ll never stop referring patients to us, they’ll never understand why we treat it the way we do, and they’ll never be able to take ownership of atopic dermatitis in some small way. It seems glaringly obvious," one pediatric dermatologist asserted.

Dr. Mathes replied: "You have a very expert opinion on this. It’s what many pediatric dermatologists would think," she said. "The pediatricians and family physicians feel differently. They would counter, ‘I do not have time to know the pathophysiology of all these things.’ They have a lot of other stuff they need to know. They have to know about the heart, the lungs, about normal development – all sorts of stuff. They have just too much to know."

The educational objectives consensus project was funded by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Dr. Mathes reported having no financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Thought leaders in pediatrics, family practice medicine, and pediatric dermatology all agree: Primary care providers need to know more – a lot more – about pediatric skin conditions.

A 20-member expert committee drawn from these disciplines has reached consensus on a lengthy wish list of educational objectives. The committee members scrutinized 235 proposed objectives in 16 content areas of pediatric dermatology. Their task was to rate the importance of each of these objectives for resident physicians who plan to see children in their general practice of primary ambulatory care or urgent care.

Ultimately 72% of the items were approved by the panel, which used the Delphi method of achieving consensus, Dr. Erin Mathes reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

It’s a successful initial step in the long-term goal of creating an online pediatric dermatology curriculum for primary care providers. Such a tool is badly needed because primary care physicians, not dermatologists, see most children with skin disease. By some estimates, skin complaints account for up to 30% of all primary care and emergency department visits. Moreover, primary care physicians rate their access to pediatric dermatologists as the third worst of all pediatric subspecialties, behind only child psychiatry and developmental and behavioral pediatrics.

Education in dermatology in medical school is quite limited. At the University of California, San Francisco, for example, where Dr. Mathes serves on the pediatric dermatology faculty, medical students receive a grand total of 7 hours of dermatologic education.

To help with this unmet need, the American Academy of Dermatology has created its online basic dermatology curriculum for self-directed learning. It has been a big hit with primary care providers and trainees. In 2013, the website received 317,000 page views, and 18% of the visitors to the site were international.

"But the AAD site lacks important pediatric dermatology content and is not particularly sophisticated in certain areas. There is a lot of room for improvement, and we can help out," Dr. Mathes explained by way of background to the SPD-supported curriculum development project.

Items that made the panel’s final cut generally fell into two broad categories: diagnosis and management of common conditions such as acne, warts, atopic dermatitis, reactive erythemas, and viral and bacterial skin disease; and recognition, triage, and appropriate referral of more rare or dangerous conditions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, vasculitis, and drug reactions.

What did not make the list were benign conditions such as lichen striatus, cysts, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and nail disorders. "A lot of the lumps and bumps weren’t deemed important," said Dr. Mathes.

Also shot down was education regarding inherited conditions, with two notable exceptions: neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis. Ichthyosis and epidermolysis bullosa were not considered to be important.

A specialty-based split emerged regarding the perceived importance of learning to perform fungal cultures and other office-based diagnostic tests. The pediatricians on the expert panel felt for the most part that they shouldn’t ask pediatric residents to know how to do them, while the family physicians and pediatric dermatologists rated that as clinically important information.

The next step will be to create educational modules to address the approved educational objectives. The modules will then be evaluated in test runs involving medical residents at collaborating institutions. Partnerships are being pursued with major medical societies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Dermatology, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the physician assistant organizations.

Several audience members at the SPD meeting rose to complain that some of the panel’s recommendations just don’t seem to make sense.

"It seems like, for example, primary care providers need to understand at least the basics of the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis or they’ll never stop referring patients to us, they’ll never understand why we treat it the way we do, and they’ll never be able to take ownership of atopic dermatitis in some small way. It seems glaringly obvious," one pediatric dermatologist asserted.

Dr. Mathes replied: "You have a very expert opinion on this. It’s what many pediatric dermatologists would think," she said. "The pediatricians and family physicians feel differently. They would counter, ‘I do not have time to know the pathophysiology of all these things.’ They have a lot of other stuff they need to know. They have to know about the heart, the lungs, about normal development – all sorts of stuff. They have just too much to know."

The educational objectives consensus project was funded by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Dr. Mathes reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SPD ANNUAL MEETING

More Vitamin D Didn’t Beat Placebo for Kids’ Atopic Dermatitis

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Vitamin D insufficiency or outright deficiency is extremely common among pediatric atopic dermatitis patients, and it correlates with worse skin disease severity.

Unfortunately, vitamin D supplementation in such patients didn’t outperform placebo in improving their atopic dermatitis severity scores in a double-blind, randomized, prospective clinical trial, Dr. Irene Lara-Corrales reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first phase of this two-part study, 77 atopic dermatitis patients aged 1-18 years, with a mean age of 7.4 years and free of potentially confounding comorbid medical conditions, had their serum vitamin D level checked. Only 27 patients, or 35%, had a normal level, defined as greater than 72.5 nmol/L, or 30 ng/mL.

Thirty-six patients were categorized as vitamin D insufficient based upon a serum level of 32.5-72.5 nmol/L, or 15-29 ng/mL. The remaining 14 patients were vitamin D deficient, with a serum level below 32.5 nmol/L or 15 ng/mL, according to Dr. Lara-Corrales of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Mean baseline atopic dermatitis severity scores using the SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Disease) system were 19.0 in the group with normal serum vitamin D and significantly worse at 28.8 in those who were vitamin D insufficient and 24.6 in patients who were vitamin D deficient.

In phase II of the study, 41 patients from phase I who had low vitamin D levels were randomized and double blinded to either 2,000 IU of vitamin D administered as cholecalciferol drops or to placebo drops for 3 months. The study hypothesis was that SCORAD ratings would improve markedly with vitamin D supplementation, based upon mounting evidence that serum vitamin D plays a key role in skin immune function.

But the hypothesis did not prevail. Although serum vitamin D levels did indeed increase significantly in response to 3 months of daily oral vitamin D supplementation, and recipients showed a hefty mean 15.35-point improvement in SCORAD scores, the placebo-treated controls demonstrated a near-identical mean 15.13-point SCORAD improvement as well.

Dr. Lara-Corrales noted that the study was completed only recently and that substantial collected data have yet to be analyzed. That includes information on sun exposure, nutritional intake, sunscreen use, and exposure to breast milk in early childhood, which may prove useful in interpreting the study results.

The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Canadian Dermatology Foundation supported the study. Dr. Lara-Corrales reported having no financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Vitamin D insufficiency or outright deficiency is extremely common among pediatric atopic dermatitis patients, and it correlates with worse skin disease severity.

Unfortunately, vitamin D supplementation in such patients didn’t outperform placebo in improving their atopic dermatitis severity scores in a double-blind, randomized, prospective clinical trial, Dr. Irene Lara-Corrales reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first phase of this two-part study, 77 atopic dermatitis patients aged 1-18 years, with a mean age of 7.4 years and free of potentially confounding comorbid medical conditions, had their serum vitamin D level checked. Only 27 patients, or 35%, had a normal level, defined as greater than 72.5 nmol/L, or 30 ng/mL.

Thirty-six patients were categorized as vitamin D insufficient based upon a serum level of 32.5-72.5 nmol/L, or 15-29 ng/mL. The remaining 14 patients were vitamin D deficient, with a serum level below 32.5 nmol/L or 15 ng/mL, according to Dr. Lara-Corrales of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Mean baseline atopic dermatitis severity scores using the SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Disease) system were 19.0 in the group with normal serum vitamin D and significantly worse at 28.8 in those who were vitamin D insufficient and 24.6 in patients who were vitamin D deficient.

In phase II of the study, 41 patients from phase I who had low vitamin D levels were randomized and double blinded to either 2,000 IU of vitamin D administered as cholecalciferol drops or to placebo drops for 3 months. The study hypothesis was that SCORAD ratings would improve markedly with vitamin D supplementation, based upon mounting evidence that serum vitamin D plays a key role in skin immune function.

But the hypothesis did not prevail. Although serum vitamin D levels did indeed increase significantly in response to 3 months of daily oral vitamin D supplementation, and recipients showed a hefty mean 15.35-point improvement in SCORAD scores, the placebo-treated controls demonstrated a near-identical mean 15.13-point SCORAD improvement as well.

Dr. Lara-Corrales noted that the study was completed only recently and that substantial collected data have yet to be analyzed. That includes information on sun exposure, nutritional intake, sunscreen use, and exposure to breast milk in early childhood, which may prove useful in interpreting the study results.

The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Canadian Dermatology Foundation supported the study. Dr. Lara-Corrales reported having no financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Vitamin D insufficiency or outright deficiency is extremely common among pediatric atopic dermatitis patients, and it correlates with worse skin disease severity.

Unfortunately, vitamin D supplementation in such patients didn’t outperform placebo in improving their atopic dermatitis severity scores in a double-blind, randomized, prospective clinical trial, Dr. Irene Lara-Corrales reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first phase of this two-part study, 77 atopic dermatitis patients aged 1-18 years, with a mean age of 7.4 years and free of potentially confounding comorbid medical conditions, had their serum vitamin D level checked. Only 27 patients, or 35%, had a normal level, defined as greater than 72.5 nmol/L, or 30 ng/mL.

Thirty-six patients were categorized as vitamin D insufficient based upon a serum level of 32.5-72.5 nmol/L, or 15-29 ng/mL. The remaining 14 patients were vitamin D deficient, with a serum level below 32.5 nmol/L or 15 ng/mL, according to Dr. Lara-Corrales of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Mean baseline atopic dermatitis severity scores using the SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Disease) system were 19.0 in the group with normal serum vitamin D and significantly worse at 28.8 in those who were vitamin D insufficient and 24.6 in patients who were vitamin D deficient.

In phase II of the study, 41 patients from phase I who had low vitamin D levels were randomized and double blinded to either 2,000 IU of vitamin D administered as cholecalciferol drops or to placebo drops for 3 months. The study hypothesis was that SCORAD ratings would improve markedly with vitamin D supplementation, based upon mounting evidence that serum vitamin D plays a key role in skin immune function.

But the hypothesis did not prevail. Although serum vitamin D levels did indeed increase significantly in response to 3 months of daily oral vitamin D supplementation, and recipients showed a hefty mean 15.35-point improvement in SCORAD scores, the placebo-treated controls demonstrated a near-identical mean 15.13-point SCORAD improvement as well.

Dr. Lara-Corrales noted that the study was completed only recently and that substantial collected data have yet to be analyzed. That includes information on sun exposure, nutritional intake, sunscreen use, and exposure to breast milk in early childhood, which may prove useful in interpreting the study results.

The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Canadian Dermatology Foundation supported the study. Dr. Lara-Corrales reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE SPD ANNUAL MEETING

More vitamin D didn’t beat placebo for kids’ atopic dermatitis

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Vitamin D insufficiency or outright deficiency is extremely common among pediatric atopic dermatitis patients, and it correlates with worse skin disease severity.

Unfortunately, vitamin D supplementation in such patients didn’t outperform placebo in improving their atopic dermatitis severity scores in a double-blind, randomized, prospective clinical trial, Dr. Irene Lara-Corrales reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first phase of this two-part study, 77 atopic dermatitis patients aged 1-18 years, with a mean age of 7.4 years and free of potentially confounding comorbid medical conditions, had their serum vitamin D level checked. Only 27 patients, or 35%, had a normal level, defined as greater than 72.5 nmol/L, or 30 ng/mL.

Thirty-six patients were categorized as vitamin D insufficient based upon a serum level of 32.5-72.5 nmol/L, or 15-29 ng/mL. The remaining 14 patients were vitamin D deficient, with a serum level below 32.5 nmol/L or 15 ng/mL, according to Dr. Lara-Corrales of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Mean baseline atopic dermatitis severity scores using the SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Disease) system were 19.0 in the group with normal serum vitamin D and significantly worse at 28.8 in those who were vitamin D insufficient and 24.6 in patients who were vitamin D deficient.

In phase II of the study, 41 patients from phase I who had low vitamin D levels were randomized and double blinded to either 2,000 IU of vitamin D administered as cholecalciferol drops or to placebo drops for 3 months. The study hypothesis was that SCORAD ratings would improve markedly with vitamin D supplementation, based upon mounting evidence that serum vitamin D plays a key role in skin immune function.

But the hypothesis did not prevail. Although serum vitamin D levels did indeed increase significantly in response to 3 months of daily oral vitamin D supplementation, and recipients showed a hefty mean 15.35-point improvement in SCORAD scores, the placebo-treated controls demonstrated a near-identical mean 15.13-point SCORAD improvement as well.

Dr. Lara-Corrales noted that the study was completed only recently and that substantial collected data have yet to be analyzed. That includes information on sun exposure, nutritional intake, sunscreen use, and exposure to breast milk in early childhood, which may prove useful in interpreting the study results.

The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Canadian Dermatology Foundation supported the study. Dr. Lara-Corrales reported having no financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Vitamin D insufficiency or outright deficiency is extremely common among pediatric atopic dermatitis patients, and it correlates with worse skin disease severity.

Unfortunately, vitamin D supplementation in such patients didn’t outperform placebo in improving their atopic dermatitis severity scores in a double-blind, randomized, prospective clinical trial, Dr. Irene Lara-Corrales reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first phase of this two-part study, 77 atopic dermatitis patients aged 1-18 years, with a mean age of 7.4 years and free of potentially confounding comorbid medical conditions, had their serum vitamin D level checked. Only 27 patients, or 35%, had a normal level, defined as greater than 72.5 nmol/L, or 30 ng/mL.

Thirty-six patients were categorized as vitamin D insufficient based upon a serum level of 32.5-72.5 nmol/L, or 15-29 ng/mL. The remaining 14 patients were vitamin D deficient, with a serum level below 32.5 nmol/L or 15 ng/mL, according to Dr. Lara-Corrales of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Mean baseline atopic dermatitis severity scores using the SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Disease) system were 19.0 in the group with normal serum vitamin D and significantly worse at 28.8 in those who were vitamin D insufficient and 24.6 in patients who were vitamin D deficient.

In phase II of the study, 41 patients from phase I who had low vitamin D levels were randomized and double blinded to either 2,000 IU of vitamin D administered as cholecalciferol drops or to placebo drops for 3 months. The study hypothesis was that SCORAD ratings would improve markedly with vitamin D supplementation, based upon mounting evidence that serum vitamin D plays a key role in skin immune function.

But the hypothesis did not prevail. Although serum vitamin D levels did indeed increase significantly in response to 3 months of daily oral vitamin D supplementation, and recipients showed a hefty mean 15.35-point improvement in SCORAD scores, the placebo-treated controls demonstrated a near-identical mean 15.13-point SCORAD improvement as well.

Dr. Lara-Corrales noted that the study was completed only recently and that substantial collected data have yet to be analyzed. That includes information on sun exposure, nutritional intake, sunscreen use, and exposure to breast milk in early childhood, which may prove useful in interpreting the study results.

The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Canadian Dermatology Foundation supported the study. Dr. Lara-Corrales reported having no financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Vitamin D insufficiency or outright deficiency is extremely common among pediatric atopic dermatitis patients, and it correlates with worse skin disease severity.

Unfortunately, vitamin D supplementation in such patients didn’t outperform placebo in improving their atopic dermatitis severity scores in a double-blind, randomized, prospective clinical trial, Dr. Irene Lara-Corrales reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first phase of this two-part study, 77 atopic dermatitis patients aged 1-18 years, with a mean age of 7.4 years and free of potentially confounding comorbid medical conditions, had their serum vitamin D level checked. Only 27 patients, or 35%, had a normal level, defined as greater than 72.5 nmol/L, or 30 ng/mL.

Thirty-six patients were categorized as vitamin D insufficient based upon a serum level of 32.5-72.5 nmol/L, or 15-29 ng/mL. The remaining 14 patients were vitamin D deficient, with a serum level below 32.5 nmol/L or 15 ng/mL, according to Dr. Lara-Corrales of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Mean baseline atopic dermatitis severity scores using the SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Disease) system were 19.0 in the group with normal serum vitamin D and significantly worse at 28.8 in those who were vitamin D insufficient and 24.6 in patients who were vitamin D deficient.

In phase II of the study, 41 patients from phase I who had low vitamin D levels were randomized and double blinded to either 2,000 IU of vitamin D administered as cholecalciferol drops or to placebo drops for 3 months. The study hypothesis was that SCORAD ratings would improve markedly with vitamin D supplementation, based upon mounting evidence that serum vitamin D plays a key role in skin immune function.

But the hypothesis did not prevail. Although serum vitamin D levels did indeed increase significantly in response to 3 months of daily oral vitamin D supplementation, and recipients showed a hefty mean 15.35-point improvement in SCORAD scores, the placebo-treated controls demonstrated a near-identical mean 15.13-point SCORAD improvement as well.

Dr. Lara-Corrales noted that the study was completed only recently and that substantial collected data have yet to be analyzed. That includes information on sun exposure, nutritional intake, sunscreen use, and exposure to breast milk in early childhood, which may prove useful in interpreting the study results.

The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Canadian Dermatology Foundation supported the study. Dr. Lara-Corrales reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE SPD ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: There may be more behind atopic dermatitis severity than just vitamin D deficiency.

Major finding: Correcting the atopic dermatitis patients’ low serum vitamin D with 2,000 IU of cholecalciferol for 3 months improved their atopic dermatitis severity scores, but only to the same extent as in placebo-treated controls.

Data source: This was a randomized, double-blind, single-center trial in which 40 atopic dermatitis patients aged 1-18 years with vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency were placed on vitamin D supplementation or placebo for 3 months.

Disclosures: The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Canadian Dermatology Foundation supported the study. Dr. Lara-Corrales reported having no financial conflicts.

Body wash offers alternative to bleach baths for atopic dermatitis

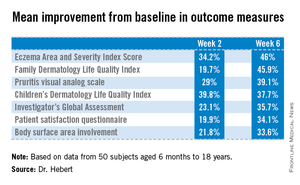

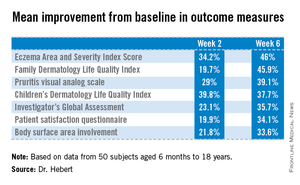

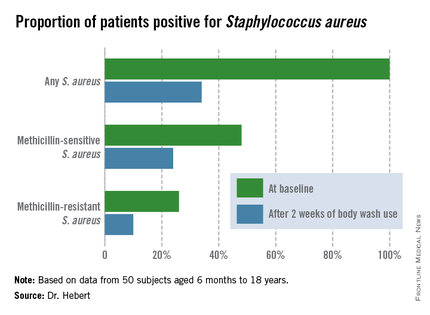

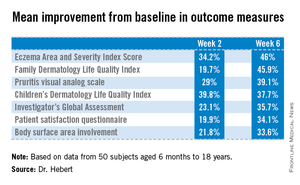

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Daily use of an over-the-counter 2-minute body wash by children and adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis resulted in marked improvement in symptoms and quality of life measures, as well as impressive changes in the skin microbiome in an open-label study.

"CLn Body Wash represents a simple and effective alternative to bleach bath use for patients who have colonization by Staphylococcus aureus and who prefer showers over baths," Dr. Adelaide A. Hebert said in presenting the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

The body wash, marketed by TopMD Skin Care, is a skin-friendly gel cleanser containing sodium hypochlorite at a concentration of 0.006%.

S. aureus colonization is common on both lesional and nonlesional skin of atopic dermatitis patients. It triggers inflammation and increases severity of the skin disease.

"I view colonization by Staph as the bully of atopic dermatitis. It really pushes and annoys the disease, and that’s the way I explain it to parents," said Dr. Hebert, professor and director of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston.

Dilute bleach baths have been shown to reduce S. aureus colonization and diminish atopic dermatitis disease severity. The typical formula is one-quarter cup of household bleach added to half a bathtub of warm water, yielding a 0.005% sodium hypochlorite solution. But many people don’t like taking baths. They prefer showers. In addition, bathtubs are uncommon in many areas outside of the United States, Dr. Hebert noted.

Ease and convenience was the impetus for the development of CLn Body Wash. The product is packaged in a 2.5-oz bottle. Patients lather a few squirts of the wash onto the skin, then rinse it off after 1-2 minutes.

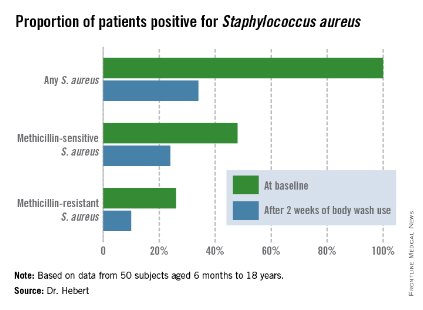

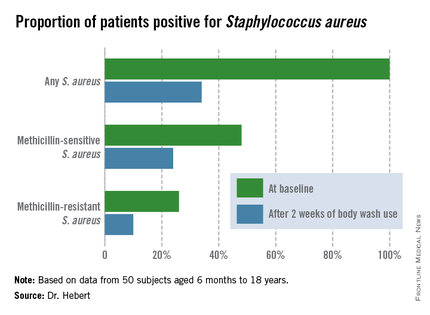

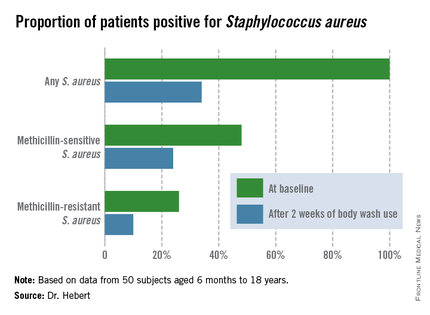

To evaluate the over-the-counter product’s effectiveness, Dr. Hebert and her coinvestigators conducted a 6-week, open-label, two-center study involving 50 subjects aged 6 months to 18 years, all with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Their mean age was 8 years. All participants were colonized by S. aureus, but none had an active infection. They were assessed at baseline, and again after 2 weeks and 6 weeks of once-daily use of the body wash.

Improvement was marked and consistent across numerous measures of disease severity and quality of life. In addition, there was a sharp reduction after 2 weeks of use in the proportion of patients who were skin-positive for S. aureus by PCR and a comparable decrease in those who were culture-positive. The prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus colonization was cut by two-thirds.

"All along the way we were able to evoke all the parameters of improvement simply by changing the colonization status of these patients. And that was very exciting," Dr. Hebert said.

But audience member Dr. Alfred T. Lane, recipient of the annual Alvin Jacobs Award at this year’s SPD meeting, noted that he found the study less than convincing.

"I’ve seen too many open-label studies that don’t work out. I really think that to have success, you want to have a placebo group. These data look fantastic. It looks extremely exciting, but without a placebo control, I’m a little bit skeptical, to be honest," declared Dr. Lane, emeritus professor of dermatology and of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The study was funded by TopMD Skin Care. Dr. Hebert reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Daily use of an over-the-counter 2-minute body wash by children and adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis resulted in marked improvement in symptoms and quality of life measures, as well as impressive changes in the skin microbiome in an open-label study.

"CLn Body Wash represents a simple and effective alternative to bleach bath use for patients who have colonization by Staphylococcus aureus and who prefer showers over baths," Dr. Adelaide A. Hebert said in presenting the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

The body wash, marketed by TopMD Skin Care, is a skin-friendly gel cleanser containing sodium hypochlorite at a concentration of 0.006%.

S. aureus colonization is common on both lesional and nonlesional skin of atopic dermatitis patients. It triggers inflammation and increases severity of the skin disease.

"I view colonization by Staph as the bully of atopic dermatitis. It really pushes and annoys the disease, and that’s the way I explain it to parents," said Dr. Hebert, professor and director of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston.

Dilute bleach baths have been shown to reduce S. aureus colonization and diminish atopic dermatitis disease severity. The typical formula is one-quarter cup of household bleach added to half a bathtub of warm water, yielding a 0.005% sodium hypochlorite solution. But many people don’t like taking baths. They prefer showers. In addition, bathtubs are uncommon in many areas outside of the United States, Dr. Hebert noted.

Ease and convenience was the impetus for the development of CLn Body Wash. The product is packaged in a 2.5-oz bottle. Patients lather a few squirts of the wash onto the skin, then rinse it off after 1-2 minutes.

To evaluate the over-the-counter product’s effectiveness, Dr. Hebert and her coinvestigators conducted a 6-week, open-label, two-center study involving 50 subjects aged 6 months to 18 years, all with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Their mean age was 8 years. All participants were colonized by S. aureus, but none had an active infection. They were assessed at baseline, and again after 2 weeks and 6 weeks of once-daily use of the body wash.

Improvement was marked and consistent across numerous measures of disease severity and quality of life. In addition, there was a sharp reduction after 2 weeks of use in the proportion of patients who were skin-positive for S. aureus by PCR and a comparable decrease in those who were culture-positive. The prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus colonization was cut by two-thirds.

"All along the way we were able to evoke all the parameters of improvement simply by changing the colonization status of these patients. And that was very exciting," Dr. Hebert said.

But audience member Dr. Alfred T. Lane, recipient of the annual Alvin Jacobs Award at this year’s SPD meeting, noted that he found the study less than convincing.

"I’ve seen too many open-label studies that don’t work out. I really think that to have success, you want to have a placebo group. These data look fantastic. It looks extremely exciting, but without a placebo control, I’m a little bit skeptical, to be honest," declared Dr. Lane, emeritus professor of dermatology and of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The study was funded by TopMD Skin Care. Dr. Hebert reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – Daily use of an over-the-counter 2-minute body wash by children and adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis resulted in marked improvement in symptoms and quality of life measures, as well as impressive changes in the skin microbiome in an open-label study.

"CLn Body Wash represents a simple and effective alternative to bleach bath use for patients who have colonization by Staphylococcus aureus and who prefer showers over baths," Dr. Adelaide A. Hebert said in presenting the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

The body wash, marketed by TopMD Skin Care, is a skin-friendly gel cleanser containing sodium hypochlorite at a concentration of 0.006%.

S. aureus colonization is common on both lesional and nonlesional skin of atopic dermatitis patients. It triggers inflammation and increases severity of the skin disease.

"I view colonization by Staph as the bully of atopic dermatitis. It really pushes and annoys the disease, and that’s the way I explain it to parents," said Dr. Hebert, professor and director of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston.

Dilute bleach baths have been shown to reduce S. aureus colonization and diminish atopic dermatitis disease severity. The typical formula is one-quarter cup of household bleach added to half a bathtub of warm water, yielding a 0.005% sodium hypochlorite solution. But many people don’t like taking baths. They prefer showers. In addition, bathtubs are uncommon in many areas outside of the United States, Dr. Hebert noted.

Ease and convenience was the impetus for the development of CLn Body Wash. The product is packaged in a 2.5-oz bottle. Patients lather a few squirts of the wash onto the skin, then rinse it off after 1-2 minutes.

To evaluate the over-the-counter product’s effectiveness, Dr. Hebert and her coinvestigators conducted a 6-week, open-label, two-center study involving 50 subjects aged 6 months to 18 years, all with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Their mean age was 8 years. All participants were colonized by S. aureus, but none had an active infection. They were assessed at baseline, and again after 2 weeks and 6 weeks of once-daily use of the body wash.

Improvement was marked and consistent across numerous measures of disease severity and quality of life. In addition, there was a sharp reduction after 2 weeks of use in the proportion of patients who were skin-positive for S. aureus by PCR and a comparable decrease in those who were culture-positive. The prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus colonization was cut by two-thirds.

"All along the way we were able to evoke all the parameters of improvement simply by changing the colonization status of these patients. And that was very exciting," Dr. Hebert said.

But audience member Dr. Alfred T. Lane, recipient of the annual Alvin Jacobs Award at this year’s SPD meeting, noted that he found the study less than convincing.

"I’ve seen too many open-label studies that don’t work out. I really think that to have success, you want to have a placebo group. These data look fantastic. It looks extremely exciting, but without a placebo control, I’m a little bit skeptical, to be honest," declared Dr. Lane, emeritus professor of dermatology and of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The study was funded by TopMD Skin Care. Dr. Hebert reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE SPD ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: An effective and convenient alternative is available for atopic dermatitis patients who find bleach baths a hassle or not possible.

Major finding: Mean scores on the Eczema Area and Severity Index dropped by 46% after patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis used an OTC daily body wash for 6 weeks. Scores on the Children’s Dermatologic Life Quality Index improved by 38%.

Data source: A 6-week, open-label, two-center study including 50 pediatric patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and colonization by S. aureus.

Disclosures: The study was funded by TopMD Skin Care, which markets the OTC body wash. Dr. Hebert reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Ped derm patients embrace cosmetic camouflage

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – The impaired quality of life so common among children and teens with visible skin disorders is significantly improved through instruction in the use of cosmetic camouflage, according to data from a 6-month prospective study.

"We believe cosmetic camouflage may allow patients a protective window of time in order to adapt to or accept a new visible skin condition," Dr. Michele Ramien said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

"Visible skin conditions are a source of emotional and psychologic stress," she added. "Amongst children, differences are quickly identified and questioned by peers. The pediatric burn literature shows that visible scarring results in an array of negative responses: Stares, avoidance, teasing, bullying."

Dr. Ramien reported data from 38 patients aged 5-18 years with vascular or pigmentary disorders visible while wearing a T-shirt and pants. Two-thirds of the individuals were light skinned, and two-thirds of the skin disorders were facial. All but three of the patients were female. They were taught to use cosmetic camouflage by hospital-based cosmeticians, and they received a free 6-month supply of the products.

Mean scores on the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index improved from 5.1 (out of a theoretically possible 30) at baseline to 2.1 at 6 months. The scores of children with pigmentary conditions improved from a mean of 6.2 to 3.2, while the scores of patients with vascular anomalies improved from 4.1 at baseline to 1.0 at 6 months.

The quality-of-life improvement was comparable in dark- and light-skinned patients, according to Dr. Ramien of the University of Montreal.

Patient surveys at 1 and 6 months showed cosmetic camouflage was well tolerated and used by the majority of patients. Indeed, all but one tried the prescribed regimen during the first month. The majority of subjects used cosmetic camouflage on a daily to once-weekly basis. At the 6-month mark, all but seven patients continued to use cosmetic camouflage.

Cosmetic camouflage entails the skillful application of specialized, commercially available products that are waterproof, are opaque, adhere to damaged skin, and will last for 8-16 hours. There is ample published evidence of the quality-of-life benefits of cosmetic camouflage in adults with disfiguring skin conditions, but little evidence of effectiveness in children until recently, Dr. Ramien observed.

"The proposed drawbacks of cosmetic camouflage that you may come across in the older literature – poor coverage of textural differences and shame related to concealing one’s true identity – those are not supported in the newer literature," she said.

Physicians without ready access to a hospital-based cosmetician have several other options.

"We realized that community dermatologists are really going to be the introduction point for the majority of pediatric patients with visible skin anomalies who might benefit from cosmetic camouflage," Dr. Ramien said. "Anyone who is interested in becoming further informed can contact representatives of the various companies that market the products, or networks of cosmeticians and aestheticians in your area who are interested in developing these services for your patients. Even the online websites of many of the cosmetic camouflage producers can be very useful in learning more about what’s available," she emphasized.

Dr. Ramien reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was supported by institutional funds.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – The impaired quality of life so common among children and teens with visible skin disorders is significantly improved through instruction in the use of cosmetic camouflage, according to data from a 6-month prospective study.

"We believe cosmetic camouflage may allow patients a protective window of time in order to adapt to or accept a new visible skin condition," Dr. Michele Ramien said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

"Visible skin conditions are a source of emotional and psychologic stress," she added. "Amongst children, differences are quickly identified and questioned by peers. The pediatric burn literature shows that visible scarring results in an array of negative responses: Stares, avoidance, teasing, bullying."

Dr. Ramien reported data from 38 patients aged 5-18 years with vascular or pigmentary disorders visible while wearing a T-shirt and pants. Two-thirds of the individuals were light skinned, and two-thirds of the skin disorders were facial. All but three of the patients were female. They were taught to use cosmetic camouflage by hospital-based cosmeticians, and they received a free 6-month supply of the products.

Mean scores on the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index improved from 5.1 (out of a theoretically possible 30) at baseline to 2.1 at 6 months. The scores of children with pigmentary conditions improved from a mean of 6.2 to 3.2, while the scores of patients with vascular anomalies improved from 4.1 at baseline to 1.0 at 6 months.

The quality-of-life improvement was comparable in dark- and light-skinned patients, according to Dr. Ramien of the University of Montreal.

Patient surveys at 1 and 6 months showed cosmetic camouflage was well tolerated and used by the majority of patients. Indeed, all but one tried the prescribed regimen during the first month. The majority of subjects used cosmetic camouflage on a daily to once-weekly basis. At the 6-month mark, all but seven patients continued to use cosmetic camouflage.

Cosmetic camouflage entails the skillful application of specialized, commercially available products that are waterproof, are opaque, adhere to damaged skin, and will last for 8-16 hours. There is ample published evidence of the quality-of-life benefits of cosmetic camouflage in adults with disfiguring skin conditions, but little evidence of effectiveness in children until recently, Dr. Ramien observed.

"The proposed drawbacks of cosmetic camouflage that you may come across in the older literature – poor coverage of textural differences and shame related to concealing one’s true identity – those are not supported in the newer literature," she said.

Physicians without ready access to a hospital-based cosmetician have several other options.

"We realized that community dermatologists are really going to be the introduction point for the majority of pediatric patients with visible skin anomalies who might benefit from cosmetic camouflage," Dr. Ramien said. "Anyone who is interested in becoming further informed can contact representatives of the various companies that market the products, or networks of cosmeticians and aestheticians in your area who are interested in developing these services for your patients. Even the online websites of many of the cosmetic camouflage producers can be very useful in learning more about what’s available," she emphasized.

Dr. Ramien reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was supported by institutional funds.

COEUR D’ALENE, IDAHO – The impaired quality of life so common among children and teens with visible skin disorders is significantly improved through instruction in the use of cosmetic camouflage, according to data from a 6-month prospective study.

"We believe cosmetic camouflage may allow patients a protective window of time in order to adapt to or accept a new visible skin condition," Dr. Michele Ramien said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

"Visible skin conditions are a source of emotional and psychologic stress," she added. "Amongst children, differences are quickly identified and questioned by peers. The pediatric burn literature shows that visible scarring results in an array of negative responses: Stares, avoidance, teasing, bullying."

Dr. Ramien reported data from 38 patients aged 5-18 years with vascular or pigmentary disorders visible while wearing a T-shirt and pants. Two-thirds of the individuals were light skinned, and two-thirds of the skin disorders were facial. All but three of the patients were female. They were taught to use cosmetic camouflage by hospital-based cosmeticians, and they received a free 6-month supply of the products.

Mean scores on the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index improved from 5.1 (out of a theoretically possible 30) at baseline to 2.1 at 6 months. The scores of children with pigmentary conditions improved from a mean of 6.2 to 3.2, while the scores of patients with vascular anomalies improved from 4.1 at baseline to 1.0 at 6 months.

The quality-of-life improvement was comparable in dark- and light-skinned patients, according to Dr. Ramien of the University of Montreal.

Patient surveys at 1 and 6 months showed cosmetic camouflage was well tolerated and used by the majority of patients. Indeed, all but one tried the prescribed regimen during the first month. The majority of subjects used cosmetic camouflage on a daily to once-weekly basis. At the 6-month mark, all but seven patients continued to use cosmetic camouflage.

Cosmetic camouflage entails the skillful application of specialized, commercially available products that are waterproof, are opaque, adhere to damaged skin, and will last for 8-16 hours. There is ample published evidence of the quality-of-life benefits of cosmetic camouflage in adults with disfiguring skin conditions, but little evidence of effectiveness in children until recently, Dr. Ramien observed.

"The proposed drawbacks of cosmetic camouflage that you may come across in the older literature – poor coverage of textural differences and shame related to concealing one’s true identity – those are not supported in the newer literature," she said.

Physicians without ready access to a hospital-based cosmetician have several other options.

"We realized that community dermatologists are really going to be the introduction point for the majority of pediatric patients with visible skin anomalies who might benefit from cosmetic camouflage," Dr. Ramien said. "Anyone who is interested in becoming further informed can contact representatives of the various companies that market the products, or networks of cosmeticians and aestheticians in your area who are interested in developing these services for your patients. Even the online websites of many of the cosmetic camouflage producers can be very useful in learning more about what’s available," she emphasized.

Dr. Ramien reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was supported by institutional funds.

AT THE SPD ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Cosmetic camouflage can diminish impairments in self-esteem and quality of life in children and adolescents with visible skin conditions.

Major finding: Mean scores on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index improved from 5.1 at baseline to 2.1 6 months after instruction in the use of cosmetic camouflage.

Data source: A prospective study of 38 pediatric patients with visible skin conditions who were taught how to use cosmetic camouflage and then followed for 6 months.

Disclosures: The study was supported by institutional funds. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.