User login

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes mellitus (DM), and approximately 90% have type 2 DM (T2DM), including about 25% of veterans.1,2 The current guidelines suggest that therapy depends on a patient's comorbidities, management needs, and patient-centered treatment factors.3 About 1 in 3 adults with DM have chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as the presence of kidney damage or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, persisting for ≥ 3 months.4

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors are a class of antihyperglycemic agents acting on the SGLT-2 proteins expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubules. They exert their effects by preventing the reabsorption of filtered glucose from the tubular lumen. There are 4 SGLT-2 inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin. Empagliflozin is currently the preferred SGLT-2 inhibitor on the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary.

According to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, empagliflozin is considered when an individual has or is at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and CKD.3 SGLT-2 inhibitors are a favorable option due to their low risk for hypoglycemia while also promoting weight loss. The EMPEROR-Reduced trial demonstrated that, in addition to benefits for patients with heart failure, empagliflozin also slowed the progressive decline in kidney function in those with and without DM.5 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of empagliflozin on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with CKD at the Hershel “Woody” Williams VA Medical Center (HWWVAMC) in Huntington, West Virginia, along with other laboratory test markers.

Methods

The Marshall University Institutional Review Board #1 (Medical) and the HWWVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee each reviewed and approved this study. A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients diagnosed with T2DM and stage 3 CKD who were prescribed empagliflozin for DM management between January 1, 2015, and October 1, 2022, yielding 1771 patients. Data were obtained through the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and stored on the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) research server.

Patients were included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed empagliflozin by a VA clinician for the treatment of T2DM, had an eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, and had an initial HbA1c between 7% and 10%. Using further random sampling, patients were either excluded or divided into, those with stage 3a CKD and those with stage 3b CKD. The primary endpoint of this study was the change in HbA1c levels in patients with stage 3b CKD (eGFR 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m2) compared with stage 3a (eGFR 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) after 12 months. The secondary endpoints included effects on renal function, weight, blood pressure, incidence of adverse drug events, and cardiovascular events. Of the excluded, 38 had HbA1c < 7%, 30 had HbA1c ≥ 10%, 21 did not have data at 1-year mark, 15 had the medication discontinued due to decline in renal function, 14 discontinued their medication without documented reason, 10 discontinued their medication due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs), 12 had eGFR > 60 mL/ min/1.73 m2, 9 died within 1 year of initiation, 4 had eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 1 had no baseline eGFR, and 1 was the spouse of a veteran.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. We used t tests to examine changes within each group, along with paired t tests to compare the 2 groups. Two-sample t tests were used to analyze the continuous data at both the primary and secondary endpoints.

Results

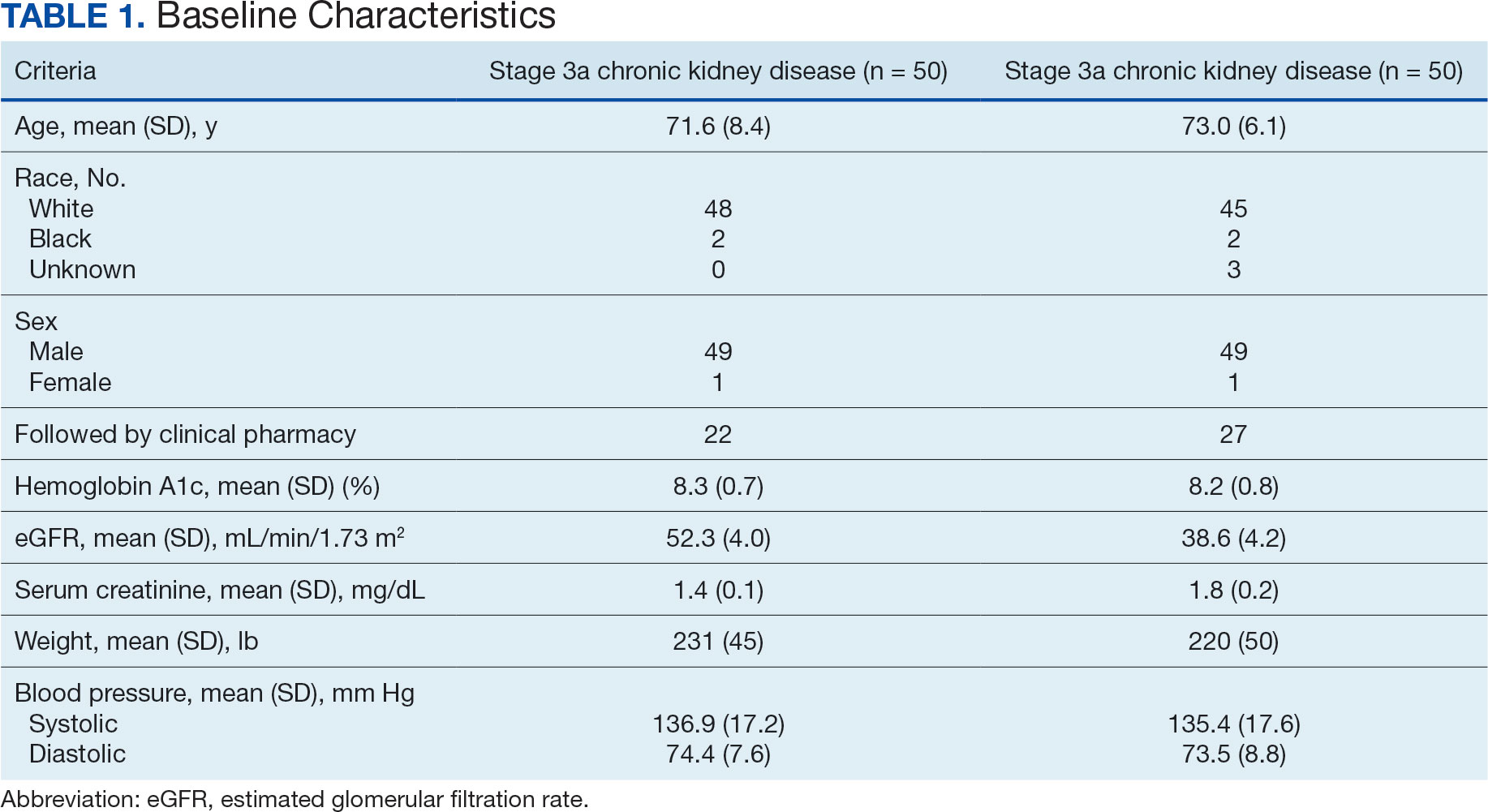

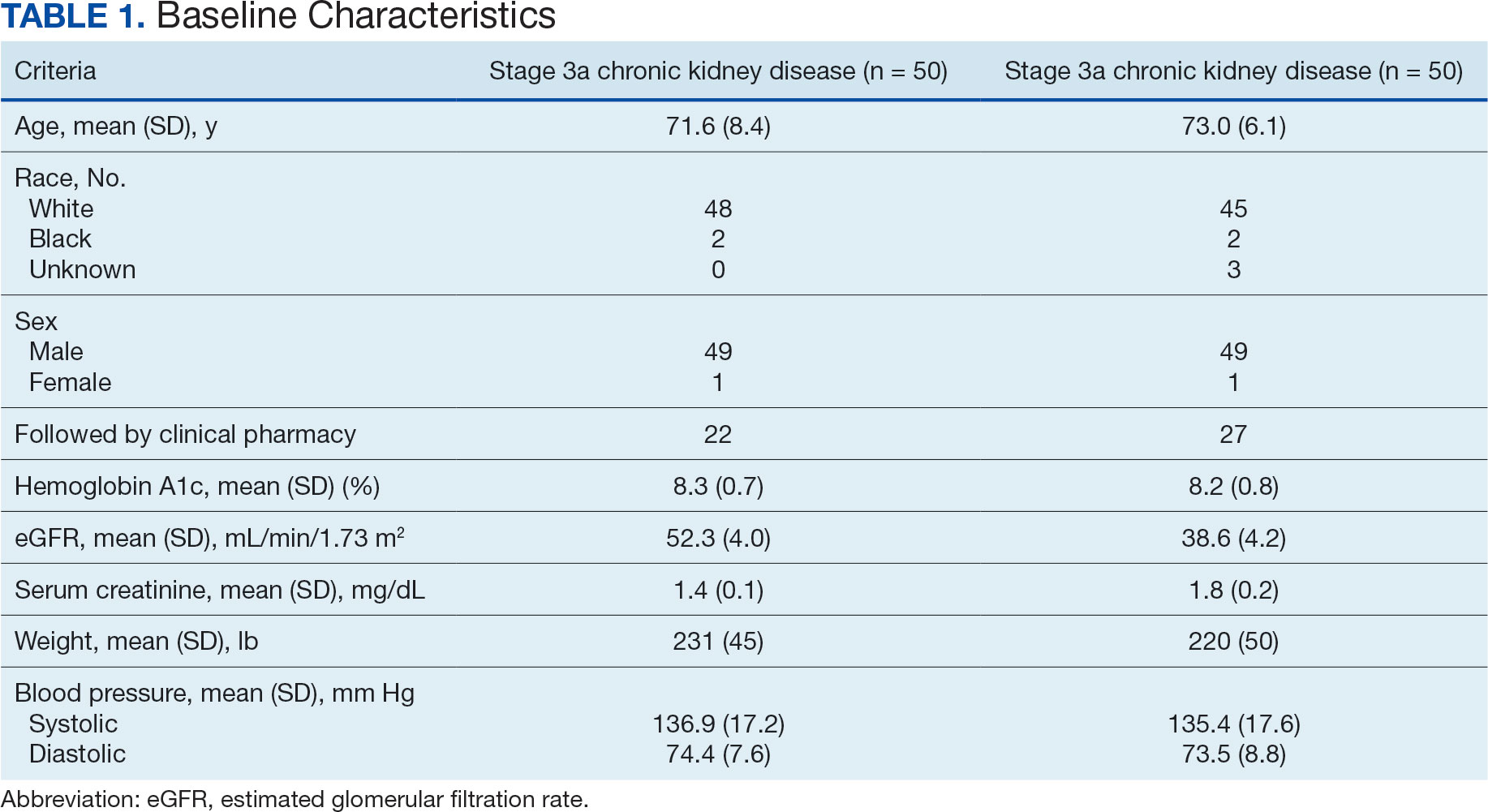

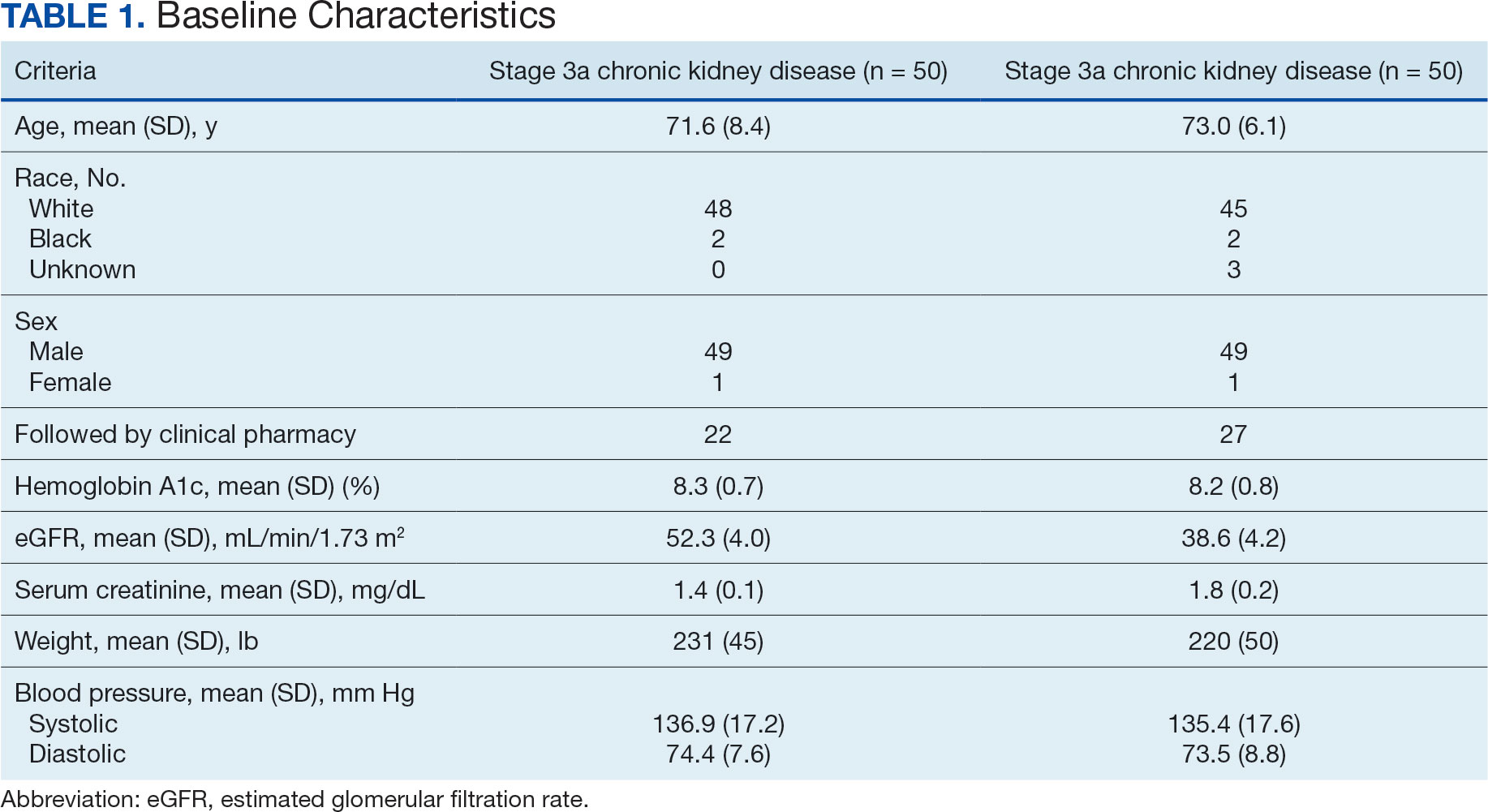

Of the 1771 patients included in the initial data set, a randomized sample of 255 charts were reviewed, 155 were excluded, and 100 were included. Fifty patients, had stage 3a CKD and 50 had stage 3b CKD. Baseline demographics were similar between the stage 3a and 3b groups (Table 1). Both groups were predominantly White and male, with mean age > 70 years.

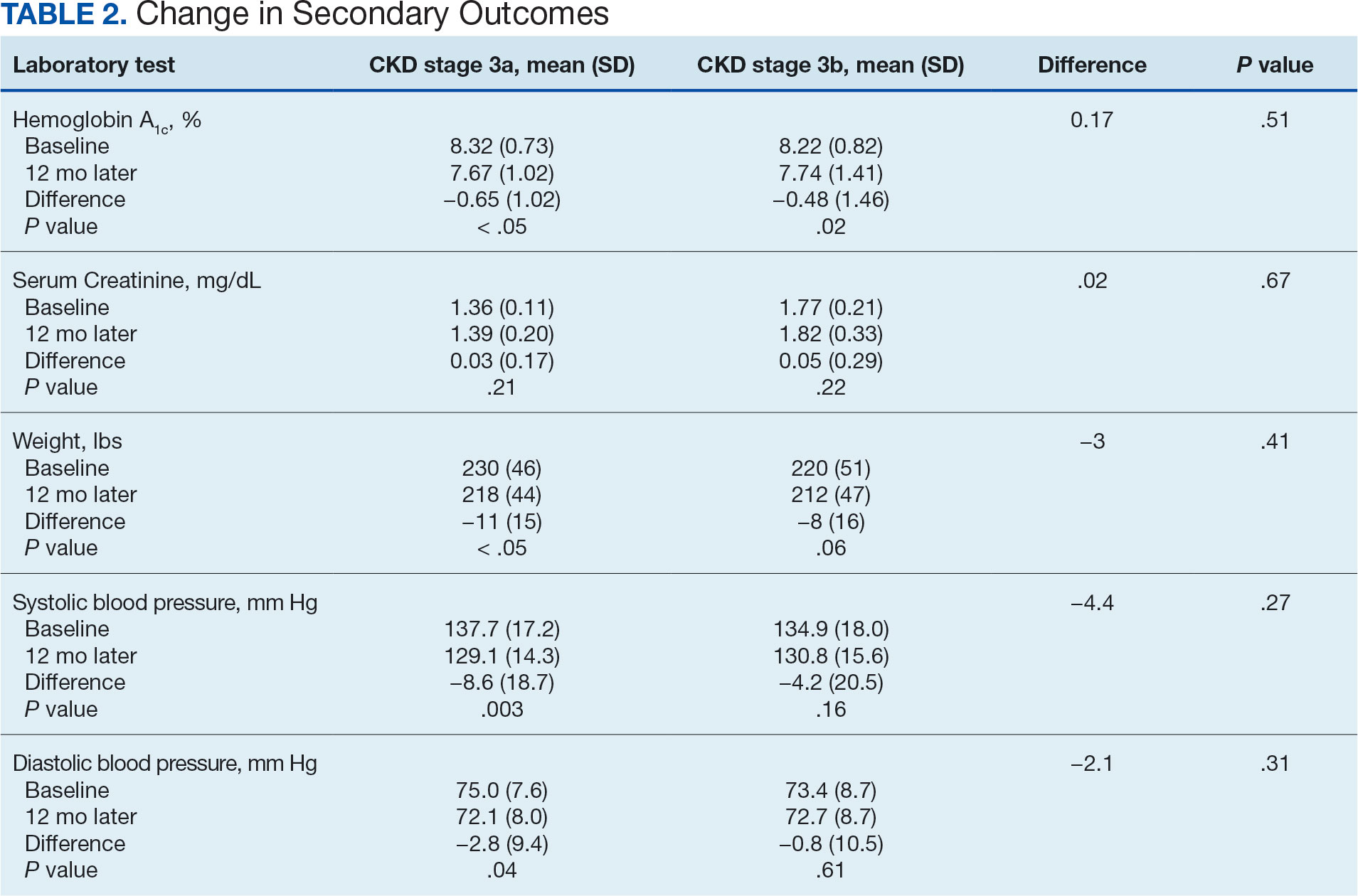

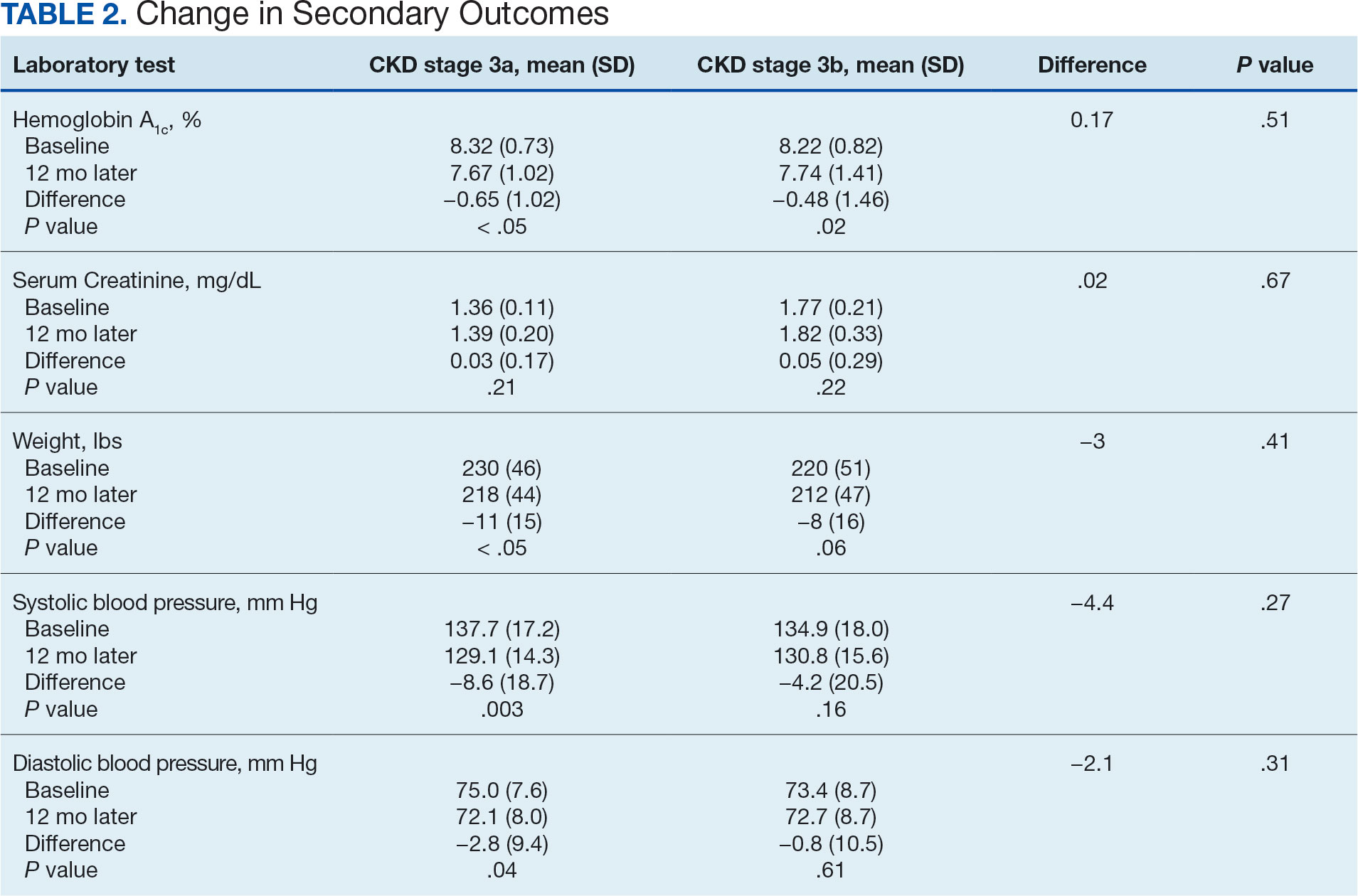

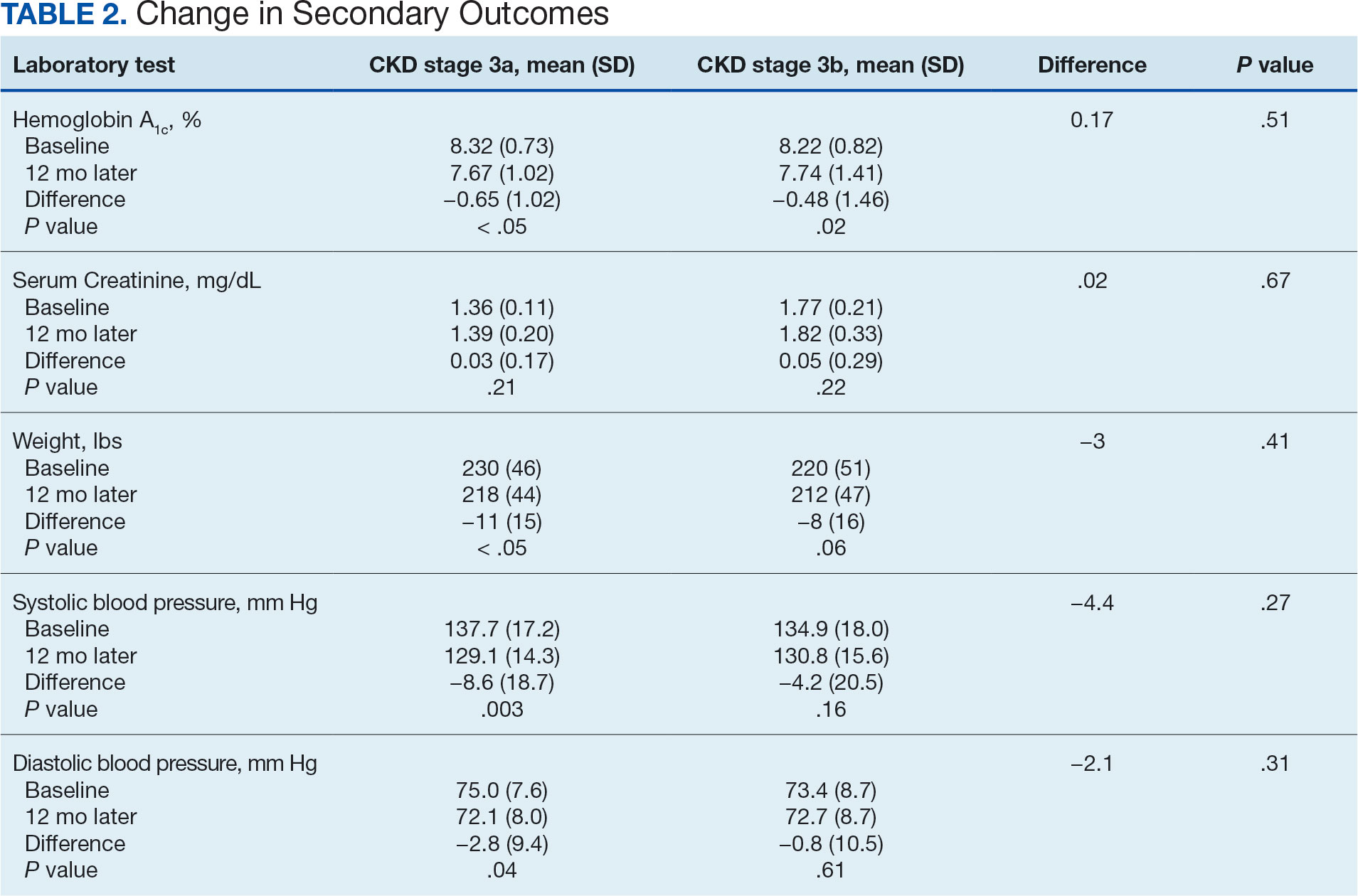

The primary endpoint was the differences in HbA1c levels over time and between groups for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD 1 year after initiation of empagliflozin. The starting doses of empagliflozin were either 12.5 mg or 25.0 mg. For both groups, the changes in HbA1c levels were statistically significant (Table 2). HbA1c levels dropped 0.65% for the stage 3a group and 0.48% for the 3b group. When compared to one another, the results were not statistically significant (P = .51).

Secondary Endpoint

There was no statistically significant difference in serum creatinine levels within each group between baselines and 1 year later for the stage 3a (P = .21) and stage 3b (P = .22) groups, or when compared to each other (P = .67). There were statistically significant changes in weight for patients in the stage 3a group (P < .05), but not for stage 3b group (P = .06) or when compared to each other (P = .41). A statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure was observed for the stage 3a group (P = .003), but not the stage 3b group (P = .16) or when compared to each other (P = .27). There were statistically significant changes in diastolic blood pressure within the stage 3a group (P = .04), but not within the stage 3b group (P = .61) or when compared to each other (P = .31).

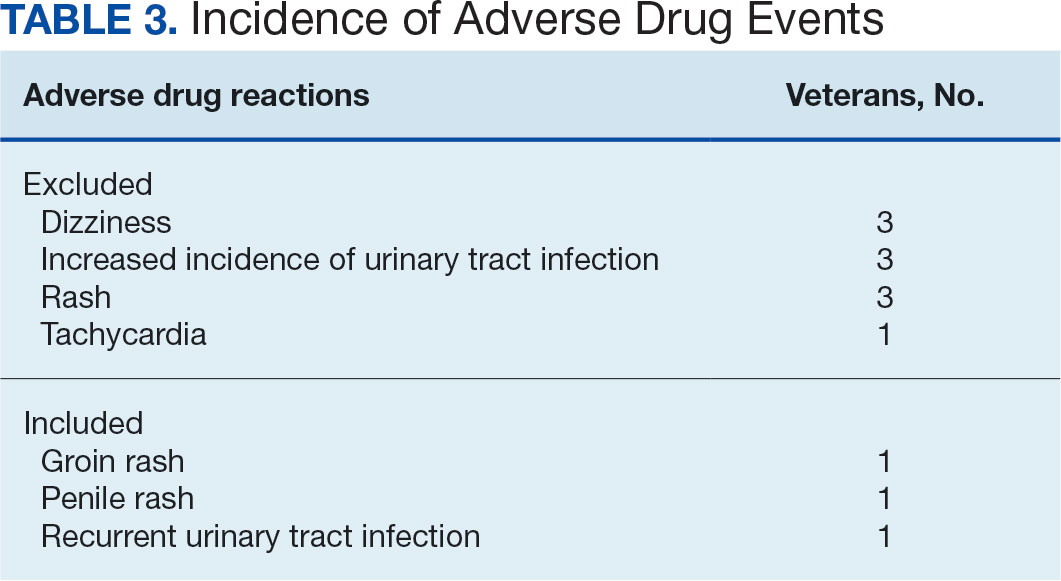

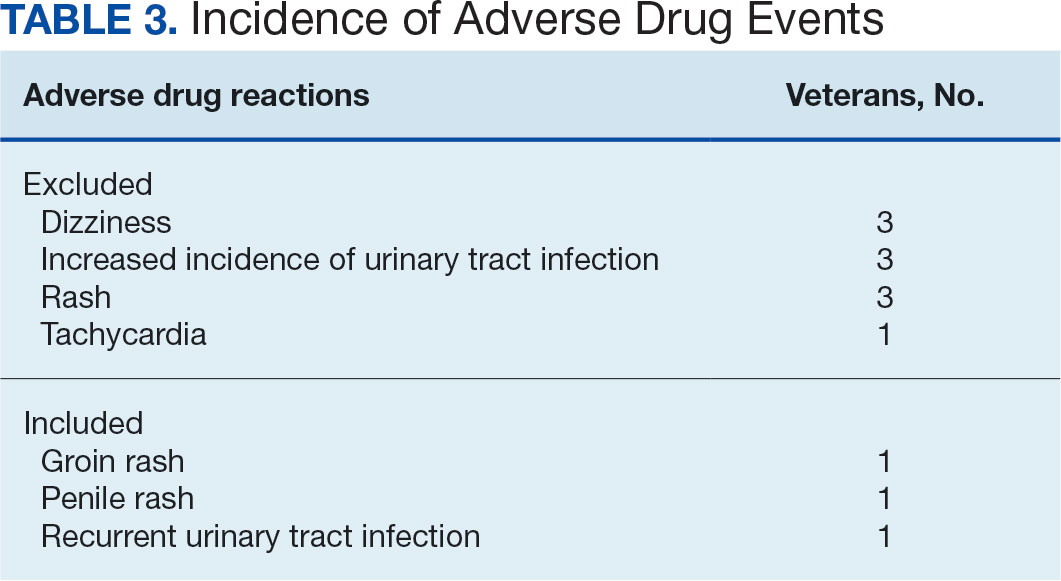

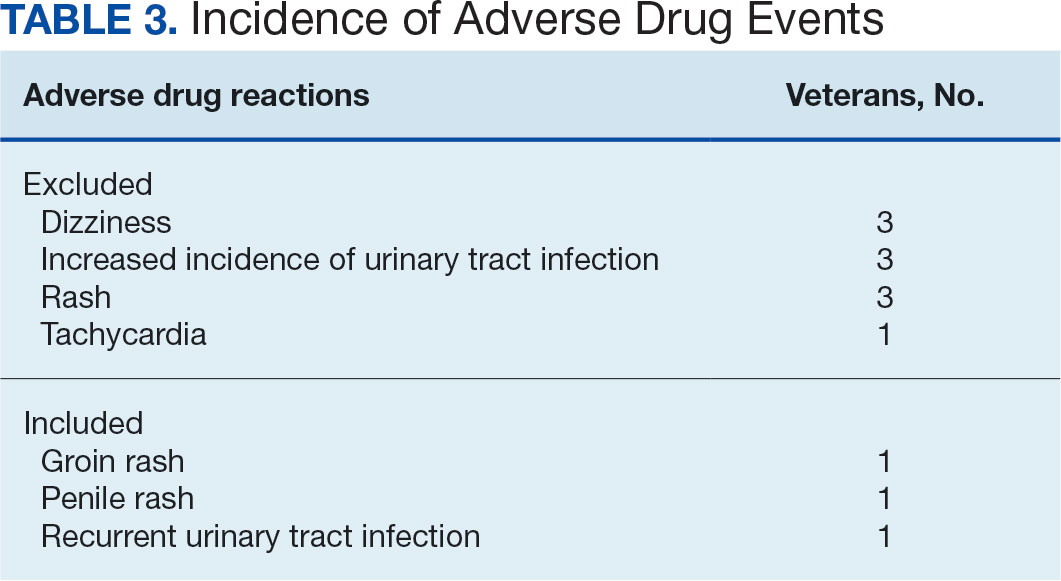

Ten patients discontinued empagliflozin before the 1-year mark due to ADRs, including dizziness, increased incidence of urinary tract infections, rash, and tachycardia (Table 3). Additionally, 3 ADRs resulted in the empagliflozin discontinuation after 1 year (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c levels for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD. With eGFR levels in these 2 groups > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients were able to achieve glycemic benefits. There were no significant changes to the serum creatinine levels. Both groups saw statistically significant changes in weight loss within their own group; however, there were no statistically significant changes when compared to each other. With both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the stage 3a group had statistically significant changes.

The EMPA-REG BP study demonstrated that empagliflozin was associated with significant and clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure and HbA1c levels compared with placebo and was well tolerated in patients with T2DM and hypertension.6,7,8

Limitations

This study had a retrospective study design, which resulted in missing information for many patients and higher rates of exclusion. The population was predominantly older, White, and male and may not reflect other populations. The starting doses of empagliflozin varied between the groups. The VA employs tablet splitting for some patients, and the available doses were either 10.0 mg, 12.5 mg, or 25.0 mg. Some prescribers start veterans at lower doses and gradually increase to the higher dose of 25.0 mg, adding to the variability in starting doses.

Patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 make it difficult to determine any potential benefit in this population. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial demonstrated that the benefits of empagliflozin treatment were consistent among patients with or without DM and regardless of eGFR at randomization.9 Furthermore, many veterans had an initial HbA1c levels outside the inclusion criteria range, which was a factor in the smaller sample size.

Conclusions

While the reduction in HbA1c levels was less in patients with stage 3b CKD compared to patients stage 3a CKD, all patients experienced a benefit. The overall incidence of ADRs was low in the study population, showing empagliflozin as a favorable choice for those with T2DM and CKD. Based on the findings of this study, empagliflozin is a potentially beneficial option for reducing HbA1c levels in patients with CKD.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 diabetes. Updated May 25, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/about-type-2-diabetes.html?CDC_AAref_Val

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA research on diabetes. Updated September 2019. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/Diabetes.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2022;40(1):10-38. doi:10.2337/cd22-as01

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes, chronic kidney disease. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/diabetes-complications/diabetes-and-chronic-kidney-disease.html

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413-1424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022190

- Tikkanen I, Narko K, Zeller C, et al. Empagliflozin reduces blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(3):420-428. doi:10.2337/dc14-1096

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504720

- Chilton R, Tikkanen I, Cannon CP, et al. Effects of empagliflozin on blood pressure and markers of arterial stiffness and vascular resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(12):1180-1193. doi:10.1111/dom.12572

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group, Herrington WG, Staplin N, et al. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):117-127. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2204233

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes mellitus (DM), and approximately 90% have type 2 DM (T2DM), including about 25% of veterans.1,2 The current guidelines suggest that therapy depends on a patient's comorbidities, management needs, and patient-centered treatment factors.3 About 1 in 3 adults with DM have chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as the presence of kidney damage or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, persisting for ≥ 3 months.4

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors are a class of antihyperglycemic agents acting on the SGLT-2 proteins expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubules. They exert their effects by preventing the reabsorption of filtered glucose from the tubular lumen. There are 4 SGLT-2 inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin. Empagliflozin is currently the preferred SGLT-2 inhibitor on the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary.

According to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, empagliflozin is considered when an individual has or is at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and CKD.3 SGLT-2 inhibitors are a favorable option due to their low risk for hypoglycemia while also promoting weight loss. The EMPEROR-Reduced trial demonstrated that, in addition to benefits for patients with heart failure, empagliflozin also slowed the progressive decline in kidney function in those with and without DM.5 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of empagliflozin on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with CKD at the Hershel “Woody” Williams VA Medical Center (HWWVAMC) in Huntington, West Virginia, along with other laboratory test markers.

Methods

The Marshall University Institutional Review Board #1 (Medical) and the HWWVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee each reviewed and approved this study. A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients diagnosed with T2DM and stage 3 CKD who were prescribed empagliflozin for DM management between January 1, 2015, and October 1, 2022, yielding 1771 patients. Data were obtained through the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and stored on the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) research server.

Patients were included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed empagliflozin by a VA clinician for the treatment of T2DM, had an eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, and had an initial HbA1c between 7% and 10%. Using further random sampling, patients were either excluded or divided into, those with stage 3a CKD and those with stage 3b CKD. The primary endpoint of this study was the change in HbA1c levels in patients with stage 3b CKD (eGFR 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m2) compared with stage 3a (eGFR 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) after 12 months. The secondary endpoints included effects on renal function, weight, blood pressure, incidence of adverse drug events, and cardiovascular events. Of the excluded, 38 had HbA1c < 7%, 30 had HbA1c ≥ 10%, 21 did not have data at 1-year mark, 15 had the medication discontinued due to decline in renal function, 14 discontinued their medication without documented reason, 10 discontinued their medication due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs), 12 had eGFR > 60 mL/ min/1.73 m2, 9 died within 1 year of initiation, 4 had eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 1 had no baseline eGFR, and 1 was the spouse of a veteran.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. We used t tests to examine changes within each group, along with paired t tests to compare the 2 groups. Two-sample t tests were used to analyze the continuous data at both the primary and secondary endpoints.

Results

Of the 1771 patients included in the initial data set, a randomized sample of 255 charts were reviewed, 155 were excluded, and 100 were included. Fifty patients, had stage 3a CKD and 50 had stage 3b CKD. Baseline demographics were similar between the stage 3a and 3b groups (Table 1). Both groups were predominantly White and male, with mean age > 70 years.

The primary endpoint was the differences in HbA1c levels over time and between groups for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD 1 year after initiation of empagliflozin. The starting doses of empagliflozin were either 12.5 mg or 25.0 mg. For both groups, the changes in HbA1c levels were statistically significant (Table 2). HbA1c levels dropped 0.65% for the stage 3a group and 0.48% for the 3b group. When compared to one another, the results were not statistically significant (P = .51).

Secondary Endpoint

There was no statistically significant difference in serum creatinine levels within each group between baselines and 1 year later for the stage 3a (P = .21) and stage 3b (P = .22) groups, or when compared to each other (P = .67). There were statistically significant changes in weight for patients in the stage 3a group (P < .05), but not for stage 3b group (P = .06) or when compared to each other (P = .41). A statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure was observed for the stage 3a group (P = .003), but not the stage 3b group (P = .16) or when compared to each other (P = .27). There were statistically significant changes in diastolic blood pressure within the stage 3a group (P = .04), but not within the stage 3b group (P = .61) or when compared to each other (P = .31).

Ten patients discontinued empagliflozin before the 1-year mark due to ADRs, including dizziness, increased incidence of urinary tract infections, rash, and tachycardia (Table 3). Additionally, 3 ADRs resulted in the empagliflozin discontinuation after 1 year (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c levels for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD. With eGFR levels in these 2 groups > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients were able to achieve glycemic benefits. There were no significant changes to the serum creatinine levels. Both groups saw statistically significant changes in weight loss within their own group; however, there were no statistically significant changes when compared to each other. With both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the stage 3a group had statistically significant changes.

The EMPA-REG BP study demonstrated that empagliflozin was associated with significant and clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure and HbA1c levels compared with placebo and was well tolerated in patients with T2DM and hypertension.6,7,8

Limitations

This study had a retrospective study design, which resulted in missing information for many patients and higher rates of exclusion. The population was predominantly older, White, and male and may not reflect other populations. The starting doses of empagliflozin varied between the groups. The VA employs tablet splitting for some patients, and the available doses were either 10.0 mg, 12.5 mg, or 25.0 mg. Some prescribers start veterans at lower doses and gradually increase to the higher dose of 25.0 mg, adding to the variability in starting doses.

Patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 make it difficult to determine any potential benefit in this population. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial demonstrated that the benefits of empagliflozin treatment were consistent among patients with or without DM and regardless of eGFR at randomization.9 Furthermore, many veterans had an initial HbA1c levels outside the inclusion criteria range, which was a factor in the smaller sample size.

Conclusions

While the reduction in HbA1c levels was less in patients with stage 3b CKD compared to patients stage 3a CKD, all patients experienced a benefit. The overall incidence of ADRs was low in the study population, showing empagliflozin as a favorable choice for those with T2DM and CKD. Based on the findings of this study, empagliflozin is a potentially beneficial option for reducing HbA1c levels in patients with CKD.

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes mellitus (DM), and approximately 90% have type 2 DM (T2DM), including about 25% of veterans.1,2 The current guidelines suggest that therapy depends on a patient's comorbidities, management needs, and patient-centered treatment factors.3 About 1 in 3 adults with DM have chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as the presence of kidney damage or an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, persisting for ≥ 3 months.4

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors are a class of antihyperglycemic agents acting on the SGLT-2 proteins expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubules. They exert their effects by preventing the reabsorption of filtered glucose from the tubular lumen. There are 4 SGLT-2 inhibitors approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ertugliflozin. Empagliflozin is currently the preferred SGLT-2 inhibitor on the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary.

According to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, empagliflozin is considered when an individual has or is at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and CKD.3 SGLT-2 inhibitors are a favorable option due to their low risk for hypoglycemia while also promoting weight loss. The EMPEROR-Reduced trial demonstrated that, in addition to benefits for patients with heart failure, empagliflozin also slowed the progressive decline in kidney function in those with and without DM.5 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of empagliflozin on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with CKD at the Hershel “Woody” Williams VA Medical Center (HWWVAMC) in Huntington, West Virginia, along with other laboratory test markers.

Methods

The Marshall University Institutional Review Board #1 (Medical) and the HWWVAMC institutional review board and research and development committee each reviewed and approved this study. A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients diagnosed with T2DM and stage 3 CKD who were prescribed empagliflozin for DM management between January 1, 2015, and October 1, 2022, yielding 1771 patients. Data were obtained through the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and stored on the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) research server.

Patients were included if they were aged 18 to 89 years, prescribed empagliflozin by a VA clinician for the treatment of T2DM, had an eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, and had an initial HbA1c between 7% and 10%. Using further random sampling, patients were either excluded or divided into, those with stage 3a CKD and those with stage 3b CKD. The primary endpoint of this study was the change in HbA1c levels in patients with stage 3b CKD (eGFR 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m2) compared with stage 3a (eGFR 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) after 12 months. The secondary endpoints included effects on renal function, weight, blood pressure, incidence of adverse drug events, and cardiovascular events. Of the excluded, 38 had HbA1c < 7%, 30 had HbA1c ≥ 10%, 21 did not have data at 1-year mark, 15 had the medication discontinued due to decline in renal function, 14 discontinued their medication without documented reason, 10 discontinued their medication due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs), 12 had eGFR > 60 mL/ min/1.73 m2, 9 died within 1 year of initiation, 4 had eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 1 had no baseline eGFR, and 1 was the spouse of a veteran.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.15. We used t tests to examine changes within each group, along with paired t tests to compare the 2 groups. Two-sample t tests were used to analyze the continuous data at both the primary and secondary endpoints.

Results

Of the 1771 patients included in the initial data set, a randomized sample of 255 charts were reviewed, 155 were excluded, and 100 were included. Fifty patients, had stage 3a CKD and 50 had stage 3b CKD. Baseline demographics were similar between the stage 3a and 3b groups (Table 1). Both groups were predominantly White and male, with mean age > 70 years.

The primary endpoint was the differences in HbA1c levels over time and between groups for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD 1 year after initiation of empagliflozin. The starting doses of empagliflozin were either 12.5 mg or 25.0 mg. For both groups, the changes in HbA1c levels were statistically significant (Table 2). HbA1c levels dropped 0.65% for the stage 3a group and 0.48% for the 3b group. When compared to one another, the results were not statistically significant (P = .51).

Secondary Endpoint

There was no statistically significant difference in serum creatinine levels within each group between baselines and 1 year later for the stage 3a (P = .21) and stage 3b (P = .22) groups, or when compared to each other (P = .67). There were statistically significant changes in weight for patients in the stage 3a group (P < .05), but not for stage 3b group (P = .06) or when compared to each other (P = .41). A statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure was observed for the stage 3a group (P = .003), but not the stage 3b group (P = .16) or when compared to each other (P = .27). There were statistically significant changes in diastolic blood pressure within the stage 3a group (P = .04), but not within the stage 3b group (P = .61) or when compared to each other (P = .31).

Ten patients discontinued empagliflozin before the 1-year mark due to ADRs, including dizziness, increased incidence of urinary tract infections, rash, and tachycardia (Table 3). Additionally, 3 ADRs resulted in the empagliflozin discontinuation after 1 year (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c levels for patients with stage 3a and stage 3b CKD. With eGFR levels in these 2 groups > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients were able to achieve glycemic benefits. There were no significant changes to the serum creatinine levels. Both groups saw statistically significant changes in weight loss within their own group; however, there were no statistically significant changes when compared to each other. With both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the stage 3a group had statistically significant changes.

The EMPA-REG BP study demonstrated that empagliflozin was associated with significant and clinically meaningful reductions in blood pressure and HbA1c levels compared with placebo and was well tolerated in patients with T2DM and hypertension.6,7,8

Limitations

This study had a retrospective study design, which resulted in missing information for many patients and higher rates of exclusion. The population was predominantly older, White, and male and may not reflect other populations. The starting doses of empagliflozin varied between the groups. The VA employs tablet splitting for some patients, and the available doses were either 10.0 mg, 12.5 mg, or 25.0 mg. Some prescribers start veterans at lower doses and gradually increase to the higher dose of 25.0 mg, adding to the variability in starting doses.

Patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 make it difficult to determine any potential benefit in this population. The EMPA-KIDNEY trial demonstrated that the benefits of empagliflozin treatment were consistent among patients with or without DM and regardless of eGFR at randomization.9 Furthermore, many veterans had an initial HbA1c levels outside the inclusion criteria range, which was a factor in the smaller sample size.

Conclusions

While the reduction in HbA1c levels was less in patients with stage 3b CKD compared to patients stage 3a CKD, all patients experienced a benefit. The overall incidence of ADRs was low in the study population, showing empagliflozin as a favorable choice for those with T2DM and CKD. Based on the findings of this study, empagliflozin is a potentially beneficial option for reducing HbA1c levels in patients with CKD.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 diabetes. Updated May 25, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/about-type-2-diabetes.html?CDC_AAref_Val

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA research on diabetes. Updated September 2019. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/Diabetes.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2022;40(1):10-38. doi:10.2337/cd22-as01

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes, chronic kidney disease. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/diabetes-complications/diabetes-and-chronic-kidney-disease.html

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413-1424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022190

- Tikkanen I, Narko K, Zeller C, et al. Empagliflozin reduces blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(3):420-428. doi:10.2337/dc14-1096

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504720

- Chilton R, Tikkanen I, Cannon CP, et al. Effects of empagliflozin on blood pressure and markers of arterial stiffness and vascular resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(12):1180-1193. doi:10.1111/dom.12572

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group, Herrington WG, Staplin N, et al. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):117-127. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2204233

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 diabetes. Updated May 25, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/about-type-2-diabetes.html?CDC_AAref_Val

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA research on diabetes. Updated September 2019. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/va_factsheets/Diabetes.pdf

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2022;40(1):10-38. doi:10.2337/cd22-as01

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes, chronic kidney disease. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/diabetes-complications/diabetes-and-chronic-kidney-disease.html

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413-1424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022190

- Tikkanen I, Narko K, Zeller C, et al. Empagliflozin reduces blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(3):420-428. doi:10.2337/dc14-1096

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504720

- Chilton R, Tikkanen I, Cannon CP, et al. Effects of empagliflozin on blood pressure and markers of arterial stiffness and vascular resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(12):1180-1193. doi:10.1111/dom.12572

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group, Herrington WG, Staplin N, et al. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):117-127. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2204233