User login

Sigmoid colon perforation secondary to transcutaneous epicardial pacer wires.

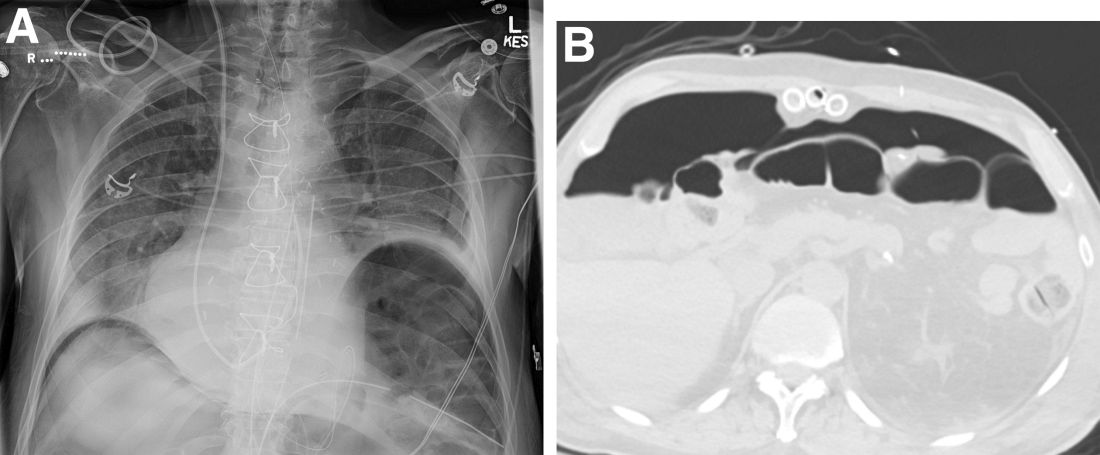

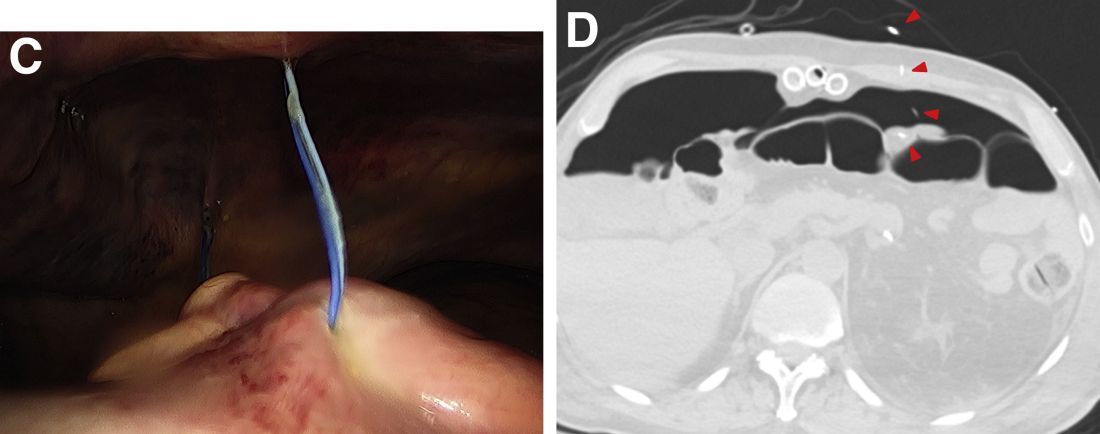

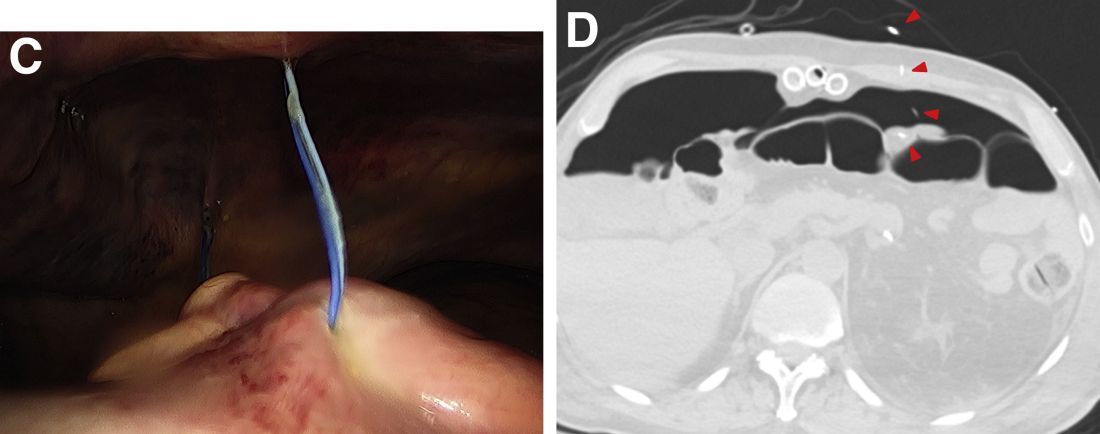

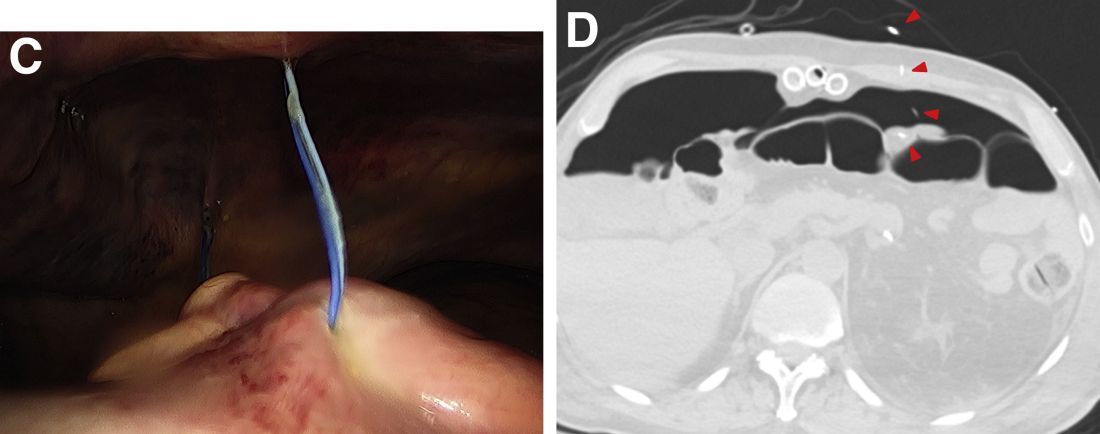

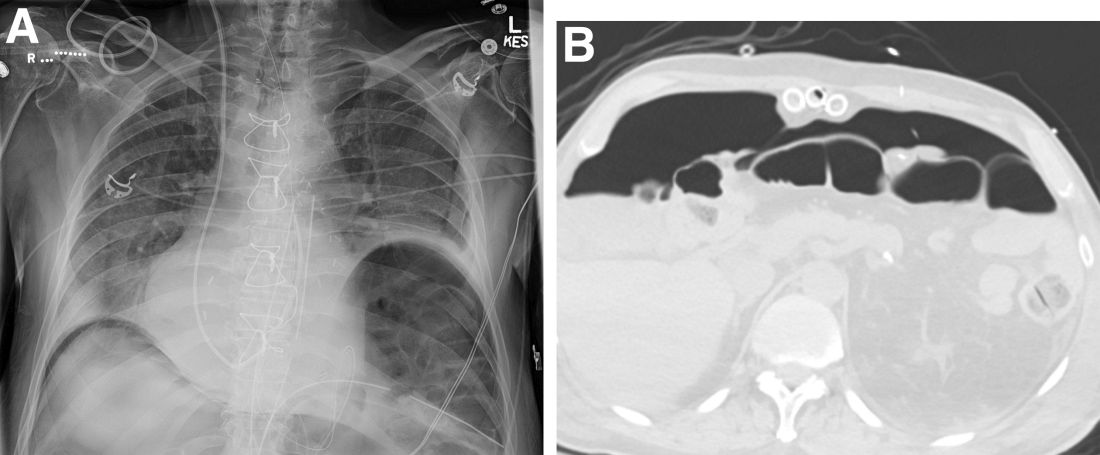

A plain film image (Figure A) shows diffusely dilated loops of bowel with subdiaphragmatic air concerning for GI viscous perforation. Dedicated cross-sectional imaging confirms intra-abdominal free air, and in representative cross section, the epicardial pacing wires can be visualized within the gastrointestinal lumen (Figure D, arrows). At the time of surgical consultation, the radiology report was notable for concern regarding possible disruption of peritoneum secondary to the difficult surgical chest tube placement in a patient with a high-riding left hemidiaphragm. Urgent laparoscopic exploration secondary to these findings unexpectedly revealed that the transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires had been inadvertently placed through the sigmoid colon (Figure C). The pacer wires were cut and removed intraoperatively. Unfortunately, 4 days after removal of pacer wires, the patient continued to have ongoing distension and was found to have sigmoid volvulus necessitating endoscopic decompression. After a prolonged hospitalization and recovery, he was discharged with a normal bowel pattern and tolerating oral intake to a skilled nursing facility.

Temporary transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires are often placed after complex cardiovascular surgical procedures. Complications from wire placement are thought to be relatively rare and are typically associated with migration into local structures after wire placement and infectious complications secondary to retained wires.1,2 Perforation of local structures during placement is less common, and GI viscous perforation in particular is not a well-characterized cause of associated morbidity.3

Our case demonstrates that, in patients with hemidiaphragm elevation, epicardial wire placement risks GI viscous perforation. Furthermore, given the frequency of concomitant surgical hardware in this patient population, identification of malpositioned epicardial wires on plain film and even cross-sectional imaging can be difficult and can delay diagnosis.

References

1. Del Nido P, Goldman BS. J Card Surg. 1989 Mar;4(1):99-103.

2. Kapoor A et al. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jul;13(1):104-6.

3. Haba J et al. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013 Feb;64(1):77-80.

Sigmoid colon perforation secondary to transcutaneous epicardial pacer wires.

A plain film image (Figure A) shows diffusely dilated loops of bowel with subdiaphragmatic air concerning for GI viscous perforation. Dedicated cross-sectional imaging confirms intra-abdominal free air, and in representative cross section, the epicardial pacing wires can be visualized within the gastrointestinal lumen (Figure D, arrows). At the time of surgical consultation, the radiology report was notable for concern regarding possible disruption of peritoneum secondary to the difficult surgical chest tube placement in a patient with a high-riding left hemidiaphragm. Urgent laparoscopic exploration secondary to these findings unexpectedly revealed that the transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires had been inadvertently placed through the sigmoid colon (Figure C). The pacer wires were cut and removed intraoperatively. Unfortunately, 4 days after removal of pacer wires, the patient continued to have ongoing distension and was found to have sigmoid volvulus necessitating endoscopic decompression. After a prolonged hospitalization and recovery, he was discharged with a normal bowel pattern and tolerating oral intake to a skilled nursing facility.

Temporary transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires are often placed after complex cardiovascular surgical procedures. Complications from wire placement are thought to be relatively rare and are typically associated with migration into local structures after wire placement and infectious complications secondary to retained wires.1,2 Perforation of local structures during placement is less common, and GI viscous perforation in particular is not a well-characterized cause of associated morbidity.3

Our case demonstrates that, in patients with hemidiaphragm elevation, epicardial wire placement risks GI viscous perforation. Furthermore, given the frequency of concomitant surgical hardware in this patient population, identification of malpositioned epicardial wires on plain film and even cross-sectional imaging can be difficult and can delay diagnosis.

References

1. Del Nido P, Goldman BS. J Card Surg. 1989 Mar;4(1):99-103.

2. Kapoor A et al. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jul;13(1):104-6.

3. Haba J et al. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013 Feb;64(1):77-80.

Sigmoid colon perforation secondary to transcutaneous epicardial pacer wires.

A plain film image (Figure A) shows diffusely dilated loops of bowel with subdiaphragmatic air concerning for GI viscous perforation. Dedicated cross-sectional imaging confirms intra-abdominal free air, and in representative cross section, the epicardial pacing wires can be visualized within the gastrointestinal lumen (Figure D, arrows). At the time of surgical consultation, the radiology report was notable for concern regarding possible disruption of peritoneum secondary to the difficult surgical chest tube placement in a patient with a high-riding left hemidiaphragm. Urgent laparoscopic exploration secondary to these findings unexpectedly revealed that the transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires had been inadvertently placed through the sigmoid colon (Figure C). The pacer wires were cut and removed intraoperatively. Unfortunately, 4 days after removal of pacer wires, the patient continued to have ongoing distension and was found to have sigmoid volvulus necessitating endoscopic decompression. After a prolonged hospitalization and recovery, he was discharged with a normal bowel pattern and tolerating oral intake to a skilled nursing facility.

Temporary transcutaneous epicardial pacing wires are often placed after complex cardiovascular surgical procedures. Complications from wire placement are thought to be relatively rare and are typically associated with migration into local structures after wire placement and infectious complications secondary to retained wires.1,2 Perforation of local structures during placement is less common, and GI viscous perforation in particular is not a well-characterized cause of associated morbidity.3

Our case demonstrates that, in patients with hemidiaphragm elevation, epicardial wire placement risks GI viscous perforation. Furthermore, given the frequency of concomitant surgical hardware in this patient population, identification of malpositioned epicardial wires on plain film and even cross-sectional imaging can be difficult and can delay diagnosis.

References

1. Del Nido P, Goldman BS. J Card Surg. 1989 Mar;4(1):99-103.

2. Kapoor A et al. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011 Jul;13(1):104-6.

3. Haba J et al. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013 Feb;64(1):77-80.

Question: An 82-year-old man was admitted for urgent coronary artery bypass and concurrent mitral valve repair. Intraoperatively, he underwent cardiopulmonary bypass, epicardial pacing, and placement of two anterior mediastinal and one pleural chest tubes. After a relatively unremarkable initial postoperative course and nonnarcotic pain control, concern for ileus developed on postoperative day 4. A nasogastric tube was placed out of concern for worsening somnolence, nausea, and the inability to safely tolerate oral intake. The patient had been passing flatus but had yet to have a bowel movement since the operation. Physical examination at the time was notable for a soft abdomen with diffuse tenderness and voluntary guarding. Subsequent plain film imaging to confirm nasogastric tube placement (Figure A) and follow-up computed tomography imaging (Figure B) are shown.

What's the diagnosis?