User login

Case

A 66-year-old Caucasian female with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 55% predicted), obesity, hypertension, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy presents to the ED with four days of increased cough productive of yellow sputum and progressive shortness of breath. Her physical exam is notable for an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, along with diffuse expiratory wheezing with use of accessory muscles; her chest X-ray is unchanged from previous. The patient is given oxygen, nebulized bronchodilators, and one dose of IV methylprednisolone. Her symptoms do not improve significantly, and she is admitted for further management. What regimen of corticosteroids is most appropriate to treat her acute exacerbation of COPD?

Overview

COPD is the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and continues to increase in prevalence.1 Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) contribute significantly to this high mortality rate, which approaches 40% at one year in those patients requiring mechanical support.1 An exacerbation of COPD has been defined as an acute change in a patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum beyond day-to-day variability sufficient to warrant a change in therapy.2 Exacerbations commonly occur in COPD patients and often necessitate hospital admission. In fact, COPD consistently is one of the 10 most common reasons for hospitalization, with billions of dollars in associated healthcare costs.3

The goals for inpatient management of AECOPD are to provide acute symptom relief and to minimize the potential for subsequent exacerbations. These are accomplished via a multifaceted approach, including the use of bronchodilators, antibiotics, supplemental oxygen, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in certain circumstances, and systemic corticosteroids.

The administration of systemic steroids in AECOPD has been prevalent for several decades, with initial studies showing positive effects on lung function, specifically FEV1.4 Studies have demonstrated the benefit of steroids in prolonging the time to subsequent exacerbation, reducing the rate of treatment failure, and reducing length of stay (LOS).5 Corticosteroids have since become an essential component of the standard of care in AECOPD management.

Despite consensus that systemic steroids should be used in COPD exacerbations, a great deal of controversy still surrounds the optimal steroid regimen.6 Steroid use is not without risk, as steroids can lead to adverse outcomes in medically complex hospitalized patients (see Table 1, below). Current guidelines provide limited guidance as to the optimal route of administration, dosing regimen, or length of therapy; clinical practice varies widely.

Review of the Data

Administration route: intravenous (IV) vs. oral. The use of steroids in AECOPD began with such IV formulations as methylprednisolone, and this became the typical method of treating hospitalized patients. This practice was validated in a multicenter Veterans Affairs trial, which demonstrated decreased risk of treatment failure (defined as all-cause mortality, need for intubation, readmission for COPD, or intensification of pharmacologic therapy) for patients randomized to receive an IV-to-oral steroid regimen compared with those randomized to placebo.5 Patients receiving steroids also had shorter LOS and improvements in FEV1 after the first day of treatment. Subsequent randomized controlled trials in patients with AECOPD demonstrated the benefit of oral regimens compared with placebo with regard to FEV1, LOS, and risk of treatment failure.6,7,8

Similarities in the bioavailability of oral and IV steroids have been known for a long time.9 Comparisons in efficacy initially were completed in the management of acute asthma exacerbations, with increasing evidence, including a meta-analysis, demonstrating no difference in improvement in pulmonary function and in preventing relapse of exacerbations for oral compared with IV steroids.10 However, only recently have oral and IV steroids been compared in the treatment of AECOPD. De Jong et al randomized more than 200 patients hospitalized for AECOPD to 60 mg of either IV or oral prednisolone for five days, followed by a week of an oral taper.11 There were no significant differences in treatment failure between the IV and oral groups (62% vs. 56%, respectively, at 90 days; one-sided lower bound of the 95% confidence interval [CI], −5.8%).

A large observational study by Lindenauer et al, including nearly 80,000 AECOPD patients admitted at more than 400 hospitals, added further support to the idea that oral and IV steroids were comparable in efficacy.12 In this study, multivariate analysis found no difference in treatment failure between oral and IV groups (odds ratio [OR] 0.93; 95% CI, 0.84-1.02). The authors also found, however, that current clinical practice still overwhelmingly favors intravenous steroids, with 92% of study patients initially being administered IV steroids.12

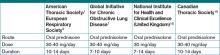

Based on the evidence from de Jong and Lindenauer, it appears that there is no significant benefit to the use of IV over oral steroids. Additionally, there is evidence for oral administration being associated with beneficial effects on cost and hospital LOS.12 Oral steroids, therefore, are the preferred route of administration to treat a hospitalized patient with AECOPD, unless the patient is unable to tolerate oral medications. Current guidelines support the practice of giving oral steroids as first-line treatment for AECOPD (see Table 2, above).

High dose vs. low dose. Another important clinical issue concerns the dosing of steroids. The randomized trials examining the use of corticosteroids in AECOPD vary widely in the dosages studied. Further, the majority of these trials have compared steroids to placebo, rather than comparing different dosage regimens. The agents studied have included prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and hydrocortisone, or combinations thereof. In order to compare regimens of these different drugs, steroid doses often are converted into prednisone equivalents (see Table 3, below). Though no guidelines define “high dose” and “low dose,” some studies have designated doses of >80 mg prednisone equivalents daily as high-dose and prednisone equivalents of ≤80 mg daily as low-dose.13,14

Starting doses of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of AECOPD in clinical studies range from prednisone equivalents of 30 mg daily to 625 mg on the first day of treatment.5,8 No randomized studies of high- versus low-dose steroid regimens have been conducted. One retrospective chart review of 145 AECOPD admissions evaluated outcomes among patients who were given higher (mean daily dose >80 mg prednisone equivalent) and lower (mean daily dose of ≤80 mg prednisone) doses.14 The authors found that patients who received higher doses of steroids had significantly longer LOS compared with those who received lower doses, especially among the subset of patients who were admitted to the floor rather than the ICU, though this analysis did not adjust for severity of illness. In this study, the most striking finding noted by the authors was the wide variability in the steroid doses prescribed for the inpatient treatment of AECOPD.

More recently, the study by Lindenauer et al examined outcomes between patients treated with high-dose IV steroids (equivalent of 120 mg-800 mg of prednisone on the first or second day of treatment) compared to low-dose oral steroids (prednisone equivalents of 20 mg-80 mg per day).12 The authors found no differences between the two groups regarding the rate of treatment failure, defined by initiation of mechanical ventilation after the second hospital day, in-hospital mortality, or readmission for COPD within 30 days of discharge. After multivariate adjustment, including the propensity for oral treatment, the low-dose oral therapy group was found to have lower risk of treatment failure, shorter LOS, and lower total hospital cost.

Despite the heterogeneity of the published data and the lack of randomized trials, the existing evidence suggests that low-dose prednisone (or equivalent) is similar in efficacy to higher doses and generally is associated with shorter hospital stays. Recognizing these benefits, guidelines do favor initiating treatment with low-dose steroids in patients admitted with AECOPD. The most recent publications from the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force (ATS/ERS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), the National Clinical Guidelines Centre in the United Kingdom, and the Canadian Thoracic Society all recommend equivalent dosing of prednisone in patients admitted with AECOPD who are able to tolerate oral intake (see Table 2).1,2,15,16

Duration. As with the dosing of systemic corticosteroids in AECOPD, the optimal duration of treatment is not well-established. National and international consensus panels vary in their recommendations, as outlined in Table 2. This may be related to the variability in length of treatment found in the literature.

Treatment durations ranging from one day to eight weeks have been studied in inpatients with AECOPD. The landmark randomized controlled trial by Niewoehner and colleagues compared two-week and eight-week courses of systemic corticosteroids and found no difference in the rates of treatment failure, which included death, need for mechanical ventilation, readmission for COPD, and intensification of pharmacologic therapy.5 Based on these results, many experts have concluded that there is no benefit to steroid courses lasting beyond two weeks.

Although improvements in outcomes have been demonstrated with corticosteroid regimens as short as three days compared with placebo, most of the randomized controlled trials have included courses of seven to 14 days.4 Given the risks of adverse events (e.g. hyperglycemia) that are associated with systemic administration of steroids, the shortest effective duration should be considered.

In both clinical practice and clinical studies, steroid regimens often include a taper. A study by Vondracek and Hemstreet found that 79% of hospital discharges for AECOPD included a tapered corticosteroid regimen.14 From a physiologic standpoint, durations of corticosteroid treatment approximately three weeks or less, regardless of dosage, should not lead to adrenal suppression.17 There also is no evidence to suggest that abrupt discontinuation of steroids leads to clinical worsening of disease, and complicated steroid tapers are a potential source of medication errors after hospital discharge.18 Furthermore, the clinical guidelines do not address the tapering of corticosteroids. Therefore, there is a lack of evidence advocating for or against the use of tapered steroid regimens in AECOPD.

Back to the Case

In addition to standard treatment modalities for AECOPD, our patient was administered oral prednisone 40 mg daily. She experienced steroid-induced hyperglycemia, which was corrected with adjustment of her insulin regimen. The patient’s pulmonary symptoms improved within 72 hours, and she was discharged home on hospital day four to complete a seven-day steroid course. At hospital discharge, she was administered influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations, and she was instructed to resume her usual insulin dosing once she finished her prednisone course.

Overview

In the management of AECOPD, there remains a lack of consensus in defining the ideal steroid regimen. Based on current literature, the use of low-dose oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone 40 mg daily, for a seven- to 14-day course is recommended. TH

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is an assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

References

- From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2010. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/GuidelineItem.asp?intId=989. Accessed Feb. 21, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932-946.

- Morbidity and mortality: 2009 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases. National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/2009_ChartBook.pdf. Accessed Feb. 24, 2011.

- Albert RK, Martin TR, Lewis SW. Controlled trial of methylprednisolone in patients with chronic bronchitis and acute respiratory insufficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(6):753-758.

- Niewoehner DE, Erbland ML, Deupree RH, et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(25):1941-1947.

- Thompson WH, Nielson C, Carvalho P, Charan NB, Crowley JJ. Controlled trial of oral prednisone in outpatients with acute COPD exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:407-412.

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1608-1613.

- Davies L, Angus RM, Calverley PM. Oral corticosteroids in patients admitted to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9177):456-460.

- Al-Habet S, Rogers HJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral prednisolone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;10(5):503-508.

- Rowe BH, Keller JL, Oxman AD. Effectiveness of steroid therapy in acute exacerbations of asthma: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:301-310.

- De Jong YP, Uil SM, Grotjohan HP, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA, van den Berg JW. Oral or IV prednisolone in the treatment of COPD exacerbations: A randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1741-1747.

- Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367.

- Manser R, Reid D, Abramsom MJ. Corticosteroids for acute severe asthma in hospitalized patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001740.

- Vondracek SF, Hemstreet BA. Retrospective evaluation of systemic corticosteroids for the management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:645-652.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Feb. 21, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14 Suppl B:5B-32B.

- Webb J, Clark TJ. Recovery of plasma corticotrophin and cortisol levels after three-week course of prednisolone. Thorax. 1981;36:22-24.

- O’Driscoll BR, Kalra S, Wilson M, Pickering CA, Carroll KB, Woodcock AA. Double-blind trial of steroid tapering in acute asthma. Lancet. 1993; 341:324-7.

Case

A 66-year-old Caucasian female with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 55% predicted), obesity, hypertension, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy presents to the ED with four days of increased cough productive of yellow sputum and progressive shortness of breath. Her physical exam is notable for an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, along with diffuse expiratory wheezing with use of accessory muscles; her chest X-ray is unchanged from previous. The patient is given oxygen, nebulized bronchodilators, and one dose of IV methylprednisolone. Her symptoms do not improve significantly, and she is admitted for further management. What regimen of corticosteroids is most appropriate to treat her acute exacerbation of COPD?

Overview

COPD is the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and continues to increase in prevalence.1 Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) contribute significantly to this high mortality rate, which approaches 40% at one year in those patients requiring mechanical support.1 An exacerbation of COPD has been defined as an acute change in a patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum beyond day-to-day variability sufficient to warrant a change in therapy.2 Exacerbations commonly occur in COPD patients and often necessitate hospital admission. In fact, COPD consistently is one of the 10 most common reasons for hospitalization, with billions of dollars in associated healthcare costs.3

The goals for inpatient management of AECOPD are to provide acute symptom relief and to minimize the potential for subsequent exacerbations. These are accomplished via a multifaceted approach, including the use of bronchodilators, antibiotics, supplemental oxygen, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in certain circumstances, and systemic corticosteroids.

The administration of systemic steroids in AECOPD has been prevalent for several decades, with initial studies showing positive effects on lung function, specifically FEV1.4 Studies have demonstrated the benefit of steroids in prolonging the time to subsequent exacerbation, reducing the rate of treatment failure, and reducing length of stay (LOS).5 Corticosteroids have since become an essential component of the standard of care in AECOPD management.

Despite consensus that systemic steroids should be used in COPD exacerbations, a great deal of controversy still surrounds the optimal steroid regimen.6 Steroid use is not without risk, as steroids can lead to adverse outcomes in medically complex hospitalized patients (see Table 1, below). Current guidelines provide limited guidance as to the optimal route of administration, dosing regimen, or length of therapy; clinical practice varies widely.

Review of the Data

Administration route: intravenous (IV) vs. oral. The use of steroids in AECOPD began with such IV formulations as methylprednisolone, and this became the typical method of treating hospitalized patients. This practice was validated in a multicenter Veterans Affairs trial, which demonstrated decreased risk of treatment failure (defined as all-cause mortality, need for intubation, readmission for COPD, or intensification of pharmacologic therapy) for patients randomized to receive an IV-to-oral steroid regimen compared with those randomized to placebo.5 Patients receiving steroids also had shorter LOS and improvements in FEV1 after the first day of treatment. Subsequent randomized controlled trials in patients with AECOPD demonstrated the benefit of oral regimens compared with placebo with regard to FEV1, LOS, and risk of treatment failure.6,7,8

Similarities in the bioavailability of oral and IV steroids have been known for a long time.9 Comparisons in efficacy initially were completed in the management of acute asthma exacerbations, with increasing evidence, including a meta-analysis, demonstrating no difference in improvement in pulmonary function and in preventing relapse of exacerbations for oral compared with IV steroids.10 However, only recently have oral and IV steroids been compared in the treatment of AECOPD. De Jong et al randomized more than 200 patients hospitalized for AECOPD to 60 mg of either IV or oral prednisolone for five days, followed by a week of an oral taper.11 There were no significant differences in treatment failure between the IV and oral groups (62% vs. 56%, respectively, at 90 days; one-sided lower bound of the 95% confidence interval [CI], −5.8%).

A large observational study by Lindenauer et al, including nearly 80,000 AECOPD patients admitted at more than 400 hospitals, added further support to the idea that oral and IV steroids were comparable in efficacy.12 In this study, multivariate analysis found no difference in treatment failure between oral and IV groups (odds ratio [OR] 0.93; 95% CI, 0.84-1.02). The authors also found, however, that current clinical practice still overwhelmingly favors intravenous steroids, with 92% of study patients initially being administered IV steroids.12

Based on the evidence from de Jong and Lindenauer, it appears that there is no significant benefit to the use of IV over oral steroids. Additionally, there is evidence for oral administration being associated with beneficial effects on cost and hospital LOS.12 Oral steroids, therefore, are the preferred route of administration to treat a hospitalized patient with AECOPD, unless the patient is unable to tolerate oral medications. Current guidelines support the practice of giving oral steroids as first-line treatment for AECOPD (see Table 2, above).

High dose vs. low dose. Another important clinical issue concerns the dosing of steroids. The randomized trials examining the use of corticosteroids in AECOPD vary widely in the dosages studied. Further, the majority of these trials have compared steroids to placebo, rather than comparing different dosage regimens. The agents studied have included prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and hydrocortisone, or combinations thereof. In order to compare regimens of these different drugs, steroid doses often are converted into prednisone equivalents (see Table 3, below). Though no guidelines define “high dose” and “low dose,” some studies have designated doses of >80 mg prednisone equivalents daily as high-dose and prednisone equivalents of ≤80 mg daily as low-dose.13,14

Starting doses of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of AECOPD in clinical studies range from prednisone equivalents of 30 mg daily to 625 mg on the first day of treatment.5,8 No randomized studies of high- versus low-dose steroid regimens have been conducted. One retrospective chart review of 145 AECOPD admissions evaluated outcomes among patients who were given higher (mean daily dose >80 mg prednisone equivalent) and lower (mean daily dose of ≤80 mg prednisone) doses.14 The authors found that patients who received higher doses of steroids had significantly longer LOS compared with those who received lower doses, especially among the subset of patients who were admitted to the floor rather than the ICU, though this analysis did not adjust for severity of illness. In this study, the most striking finding noted by the authors was the wide variability in the steroid doses prescribed for the inpatient treatment of AECOPD.

More recently, the study by Lindenauer et al examined outcomes between patients treated with high-dose IV steroids (equivalent of 120 mg-800 mg of prednisone on the first or second day of treatment) compared to low-dose oral steroids (prednisone equivalents of 20 mg-80 mg per day).12 The authors found no differences between the two groups regarding the rate of treatment failure, defined by initiation of mechanical ventilation after the second hospital day, in-hospital mortality, or readmission for COPD within 30 days of discharge. After multivariate adjustment, including the propensity for oral treatment, the low-dose oral therapy group was found to have lower risk of treatment failure, shorter LOS, and lower total hospital cost.

Despite the heterogeneity of the published data and the lack of randomized trials, the existing evidence suggests that low-dose prednisone (or equivalent) is similar in efficacy to higher doses and generally is associated with shorter hospital stays. Recognizing these benefits, guidelines do favor initiating treatment with low-dose steroids in patients admitted with AECOPD. The most recent publications from the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force (ATS/ERS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), the National Clinical Guidelines Centre in the United Kingdom, and the Canadian Thoracic Society all recommend equivalent dosing of prednisone in patients admitted with AECOPD who are able to tolerate oral intake (see Table 2).1,2,15,16

Duration. As with the dosing of systemic corticosteroids in AECOPD, the optimal duration of treatment is not well-established. National and international consensus panels vary in their recommendations, as outlined in Table 2. This may be related to the variability in length of treatment found in the literature.

Treatment durations ranging from one day to eight weeks have been studied in inpatients with AECOPD. The landmark randomized controlled trial by Niewoehner and colleagues compared two-week and eight-week courses of systemic corticosteroids and found no difference in the rates of treatment failure, which included death, need for mechanical ventilation, readmission for COPD, and intensification of pharmacologic therapy.5 Based on these results, many experts have concluded that there is no benefit to steroid courses lasting beyond two weeks.

Although improvements in outcomes have been demonstrated with corticosteroid regimens as short as three days compared with placebo, most of the randomized controlled trials have included courses of seven to 14 days.4 Given the risks of adverse events (e.g. hyperglycemia) that are associated with systemic administration of steroids, the shortest effective duration should be considered.

In both clinical practice and clinical studies, steroid regimens often include a taper. A study by Vondracek and Hemstreet found that 79% of hospital discharges for AECOPD included a tapered corticosteroid regimen.14 From a physiologic standpoint, durations of corticosteroid treatment approximately three weeks or less, regardless of dosage, should not lead to adrenal suppression.17 There also is no evidence to suggest that abrupt discontinuation of steroids leads to clinical worsening of disease, and complicated steroid tapers are a potential source of medication errors after hospital discharge.18 Furthermore, the clinical guidelines do not address the tapering of corticosteroids. Therefore, there is a lack of evidence advocating for or against the use of tapered steroid regimens in AECOPD.

Back to the Case

In addition to standard treatment modalities for AECOPD, our patient was administered oral prednisone 40 mg daily. She experienced steroid-induced hyperglycemia, which was corrected with adjustment of her insulin regimen. The patient’s pulmonary symptoms improved within 72 hours, and she was discharged home on hospital day four to complete a seven-day steroid course. At hospital discharge, she was administered influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations, and she was instructed to resume her usual insulin dosing once she finished her prednisone course.

Overview

In the management of AECOPD, there remains a lack of consensus in defining the ideal steroid regimen. Based on current literature, the use of low-dose oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone 40 mg daily, for a seven- to 14-day course is recommended. TH

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is an assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

References

- From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2010. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/GuidelineItem.asp?intId=989. Accessed Feb. 21, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932-946.

- Morbidity and mortality: 2009 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases. National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/2009_ChartBook.pdf. Accessed Feb. 24, 2011.

- Albert RK, Martin TR, Lewis SW. Controlled trial of methylprednisolone in patients with chronic bronchitis and acute respiratory insufficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(6):753-758.

- Niewoehner DE, Erbland ML, Deupree RH, et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(25):1941-1947.

- Thompson WH, Nielson C, Carvalho P, Charan NB, Crowley JJ. Controlled trial of oral prednisone in outpatients with acute COPD exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:407-412.

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1608-1613.

- Davies L, Angus RM, Calverley PM. Oral corticosteroids in patients admitted to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9177):456-460.

- Al-Habet S, Rogers HJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral prednisolone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;10(5):503-508.

- Rowe BH, Keller JL, Oxman AD. Effectiveness of steroid therapy in acute exacerbations of asthma: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:301-310.

- De Jong YP, Uil SM, Grotjohan HP, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA, van den Berg JW. Oral or IV prednisolone in the treatment of COPD exacerbations: A randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1741-1747.

- Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367.

- Manser R, Reid D, Abramsom MJ. Corticosteroids for acute severe asthma in hospitalized patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001740.

- Vondracek SF, Hemstreet BA. Retrospective evaluation of systemic corticosteroids for the management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:645-652.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Feb. 21, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14 Suppl B:5B-32B.

- Webb J, Clark TJ. Recovery of plasma corticotrophin and cortisol levels after three-week course of prednisolone. Thorax. 1981;36:22-24.

- O’Driscoll BR, Kalra S, Wilson M, Pickering CA, Carroll KB, Woodcock AA. Double-blind trial of steroid tapering in acute asthma. Lancet. 1993; 341:324-7.

Case

A 66-year-old Caucasian female with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 55% predicted), obesity, hypertension, and Type 2 diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy presents to the ED with four days of increased cough productive of yellow sputum and progressive shortness of breath. Her physical exam is notable for an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, along with diffuse expiratory wheezing with use of accessory muscles; her chest X-ray is unchanged from previous. The patient is given oxygen, nebulized bronchodilators, and one dose of IV methylprednisolone. Her symptoms do not improve significantly, and she is admitted for further management. What regimen of corticosteroids is most appropriate to treat her acute exacerbation of COPD?

Overview

COPD is the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and continues to increase in prevalence.1 Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) contribute significantly to this high mortality rate, which approaches 40% at one year in those patients requiring mechanical support.1 An exacerbation of COPD has been defined as an acute change in a patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum beyond day-to-day variability sufficient to warrant a change in therapy.2 Exacerbations commonly occur in COPD patients and often necessitate hospital admission. In fact, COPD consistently is one of the 10 most common reasons for hospitalization, with billions of dollars in associated healthcare costs.3

The goals for inpatient management of AECOPD are to provide acute symptom relief and to minimize the potential for subsequent exacerbations. These are accomplished via a multifaceted approach, including the use of bronchodilators, antibiotics, supplemental oxygen, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in certain circumstances, and systemic corticosteroids.

The administration of systemic steroids in AECOPD has been prevalent for several decades, with initial studies showing positive effects on lung function, specifically FEV1.4 Studies have demonstrated the benefit of steroids in prolonging the time to subsequent exacerbation, reducing the rate of treatment failure, and reducing length of stay (LOS).5 Corticosteroids have since become an essential component of the standard of care in AECOPD management.

Despite consensus that systemic steroids should be used in COPD exacerbations, a great deal of controversy still surrounds the optimal steroid regimen.6 Steroid use is not without risk, as steroids can lead to adverse outcomes in medically complex hospitalized patients (see Table 1, below). Current guidelines provide limited guidance as to the optimal route of administration, dosing regimen, or length of therapy; clinical practice varies widely.

Review of the Data

Administration route: intravenous (IV) vs. oral. The use of steroids in AECOPD began with such IV formulations as methylprednisolone, and this became the typical method of treating hospitalized patients. This practice was validated in a multicenter Veterans Affairs trial, which demonstrated decreased risk of treatment failure (defined as all-cause mortality, need for intubation, readmission for COPD, or intensification of pharmacologic therapy) for patients randomized to receive an IV-to-oral steroid regimen compared with those randomized to placebo.5 Patients receiving steroids also had shorter LOS and improvements in FEV1 after the first day of treatment. Subsequent randomized controlled trials in patients with AECOPD demonstrated the benefit of oral regimens compared with placebo with regard to FEV1, LOS, and risk of treatment failure.6,7,8

Similarities in the bioavailability of oral and IV steroids have been known for a long time.9 Comparisons in efficacy initially were completed in the management of acute asthma exacerbations, with increasing evidence, including a meta-analysis, demonstrating no difference in improvement in pulmonary function and in preventing relapse of exacerbations for oral compared with IV steroids.10 However, only recently have oral and IV steroids been compared in the treatment of AECOPD. De Jong et al randomized more than 200 patients hospitalized for AECOPD to 60 mg of either IV or oral prednisolone for five days, followed by a week of an oral taper.11 There were no significant differences in treatment failure between the IV and oral groups (62% vs. 56%, respectively, at 90 days; one-sided lower bound of the 95% confidence interval [CI], −5.8%).

A large observational study by Lindenauer et al, including nearly 80,000 AECOPD patients admitted at more than 400 hospitals, added further support to the idea that oral and IV steroids were comparable in efficacy.12 In this study, multivariate analysis found no difference in treatment failure between oral and IV groups (odds ratio [OR] 0.93; 95% CI, 0.84-1.02). The authors also found, however, that current clinical practice still overwhelmingly favors intravenous steroids, with 92% of study patients initially being administered IV steroids.12

Based on the evidence from de Jong and Lindenauer, it appears that there is no significant benefit to the use of IV over oral steroids. Additionally, there is evidence for oral administration being associated with beneficial effects on cost and hospital LOS.12 Oral steroids, therefore, are the preferred route of administration to treat a hospitalized patient with AECOPD, unless the patient is unable to tolerate oral medications. Current guidelines support the practice of giving oral steroids as first-line treatment for AECOPD (see Table 2, above).

High dose vs. low dose. Another important clinical issue concerns the dosing of steroids. The randomized trials examining the use of corticosteroids in AECOPD vary widely in the dosages studied. Further, the majority of these trials have compared steroids to placebo, rather than comparing different dosage regimens. The agents studied have included prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and hydrocortisone, or combinations thereof. In order to compare regimens of these different drugs, steroid doses often are converted into prednisone equivalents (see Table 3, below). Though no guidelines define “high dose” and “low dose,” some studies have designated doses of >80 mg prednisone equivalents daily as high-dose and prednisone equivalents of ≤80 mg daily as low-dose.13,14

Starting doses of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of AECOPD in clinical studies range from prednisone equivalents of 30 mg daily to 625 mg on the first day of treatment.5,8 No randomized studies of high- versus low-dose steroid regimens have been conducted. One retrospective chart review of 145 AECOPD admissions evaluated outcomes among patients who were given higher (mean daily dose >80 mg prednisone equivalent) and lower (mean daily dose of ≤80 mg prednisone) doses.14 The authors found that patients who received higher doses of steroids had significantly longer LOS compared with those who received lower doses, especially among the subset of patients who were admitted to the floor rather than the ICU, though this analysis did not adjust for severity of illness. In this study, the most striking finding noted by the authors was the wide variability in the steroid doses prescribed for the inpatient treatment of AECOPD.

More recently, the study by Lindenauer et al examined outcomes between patients treated with high-dose IV steroids (equivalent of 120 mg-800 mg of prednisone on the first or second day of treatment) compared to low-dose oral steroids (prednisone equivalents of 20 mg-80 mg per day).12 The authors found no differences between the two groups regarding the rate of treatment failure, defined by initiation of mechanical ventilation after the second hospital day, in-hospital mortality, or readmission for COPD within 30 days of discharge. After multivariate adjustment, including the propensity for oral treatment, the low-dose oral therapy group was found to have lower risk of treatment failure, shorter LOS, and lower total hospital cost.

Despite the heterogeneity of the published data and the lack of randomized trials, the existing evidence suggests that low-dose prednisone (or equivalent) is similar in efficacy to higher doses and generally is associated with shorter hospital stays. Recognizing these benefits, guidelines do favor initiating treatment with low-dose steroids in patients admitted with AECOPD. The most recent publications from the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force (ATS/ERS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), the National Clinical Guidelines Centre in the United Kingdom, and the Canadian Thoracic Society all recommend equivalent dosing of prednisone in patients admitted with AECOPD who are able to tolerate oral intake (see Table 2).1,2,15,16

Duration. As with the dosing of systemic corticosteroids in AECOPD, the optimal duration of treatment is not well-established. National and international consensus panels vary in their recommendations, as outlined in Table 2. This may be related to the variability in length of treatment found in the literature.

Treatment durations ranging from one day to eight weeks have been studied in inpatients with AECOPD. The landmark randomized controlled trial by Niewoehner and colleagues compared two-week and eight-week courses of systemic corticosteroids and found no difference in the rates of treatment failure, which included death, need for mechanical ventilation, readmission for COPD, and intensification of pharmacologic therapy.5 Based on these results, many experts have concluded that there is no benefit to steroid courses lasting beyond two weeks.

Although improvements in outcomes have been demonstrated with corticosteroid regimens as short as three days compared with placebo, most of the randomized controlled trials have included courses of seven to 14 days.4 Given the risks of adverse events (e.g. hyperglycemia) that are associated with systemic administration of steroids, the shortest effective duration should be considered.

In both clinical practice and clinical studies, steroid regimens often include a taper. A study by Vondracek and Hemstreet found that 79% of hospital discharges for AECOPD included a tapered corticosteroid regimen.14 From a physiologic standpoint, durations of corticosteroid treatment approximately three weeks or less, regardless of dosage, should not lead to adrenal suppression.17 There also is no evidence to suggest that abrupt discontinuation of steroids leads to clinical worsening of disease, and complicated steroid tapers are a potential source of medication errors after hospital discharge.18 Furthermore, the clinical guidelines do not address the tapering of corticosteroids. Therefore, there is a lack of evidence advocating for or against the use of tapered steroid regimens in AECOPD.

Back to the Case

In addition to standard treatment modalities for AECOPD, our patient was administered oral prednisone 40 mg daily. She experienced steroid-induced hyperglycemia, which was corrected with adjustment of her insulin regimen. The patient’s pulmonary symptoms improved within 72 hours, and she was discharged home on hospital day four to complete a seven-day steroid course. At hospital discharge, she was administered influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations, and she was instructed to resume her usual insulin dosing once she finished her prednisone course.

Overview

In the management of AECOPD, there remains a lack of consensus in defining the ideal steroid regimen. Based on current literature, the use of low-dose oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone 40 mg daily, for a seven- to 14-day course is recommended. TH

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is an assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

References

- From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2010. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/GuidelineItem.asp?intId=989. Accessed Feb. 21, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932-946.

- Morbidity and mortality: 2009 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases. National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/2009_ChartBook.pdf. Accessed Feb. 24, 2011.

- Albert RK, Martin TR, Lewis SW. Controlled trial of methylprednisolone in patients with chronic bronchitis and acute respiratory insufficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(6):753-758.

- Niewoehner DE, Erbland ML, Deupree RH, et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(25):1941-1947.

- Thompson WH, Nielson C, Carvalho P, Charan NB, Crowley JJ. Controlled trial of oral prednisone in outpatients with acute COPD exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:407-412.

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1608-1613.

- Davies L, Angus RM, Calverley PM. Oral corticosteroids in patients admitted to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9177):456-460.

- Al-Habet S, Rogers HJ. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral prednisolone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;10(5):503-508.

- Rowe BH, Keller JL, Oxman AD. Effectiveness of steroid therapy in acute exacerbations of asthma: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:301-310.

- De Jong YP, Uil SM, Grotjohan HP, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA, van den Berg JW. Oral or IV prednisolone in the treatment of COPD exacerbations: A randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1741-1747.

- Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367.

- Manser R, Reid D, Abramsom MJ. Corticosteroids for acute severe asthma in hospitalized patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001740.

- Vondracek SF, Hemstreet BA. Retrospective evaluation of systemic corticosteroids for the management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:645-652.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Feb. 21, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14 Suppl B:5B-32B.

- Webb J, Clark TJ. Recovery of plasma corticotrophin and cortisol levels after three-week course of prednisolone. Thorax. 1981;36:22-24.

- O’Driscoll BR, Kalra S, Wilson M, Pickering CA, Carroll KB, Woodcock AA. Double-blind trial of steroid tapering in acute asthma. Lancet. 1993; 341:324-7.