User login

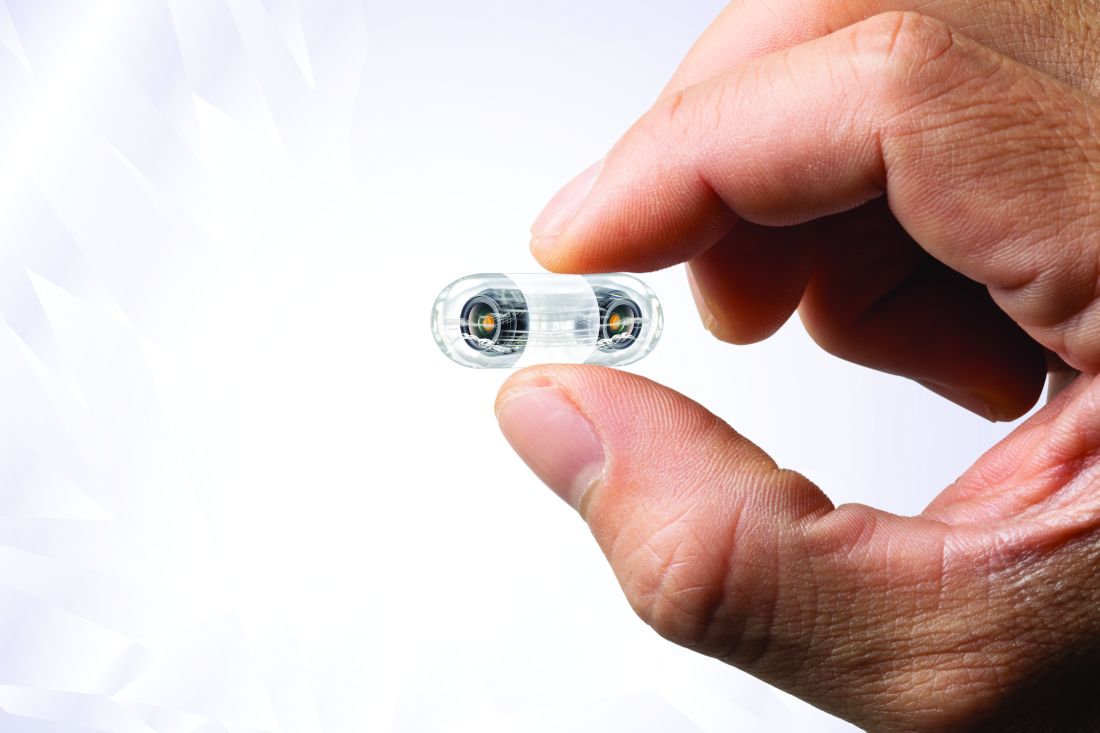

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers an alternative triage tool for acute GI bleeding that may reduce personnel exposure to SARS-CoV-2, based on a cohort study with historical controls.

VCE should be considered even when rapid coronavirus testing is available, as active bleeding is more likely to be detected when evaluated sooner, potentially sparing patients from invasive procedures, reported lead author Shahrad Hakimian, MD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worchester, and colleagues.

“Endoscopists and staff are at high risk of exposure to coronavirus through aerosols, as well as unintended, unrecognized splashes that are well known to occur frequently during routine endoscopy,” Dr. Hakimian said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although pretesting and delaying procedures as needed may mitigate risks of viral exposure, “many urgent procedures, such as endoscopic evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding, can’t really wait,” Dr. Hakimian said.

Current guidelines recommend early upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy for evaluation of GI bleeding, but Dr. Hakimian noted that two out of three initial tests are nondiagnostic, so multiple procedures are often needed to find an answer.

In 2018, a randomized, controlled trial coauthored by Dr. Hakimian’s colleagues demonstrated how VCE may be a better approach, as it more frequently detected active bleeding than standard of care (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.36-5.64).

The present study built on these findings in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Hakimian and colleagues analyzed data from 50 consecutive, hemodynamically stable patients with severe anemia or suspected GI bleeding who underwent VCE as a first-line diagnostic modality from mid-March to mid-May 2020 (COVID arm). These patients were compared with 57 consecutive patients who were evaluated for acute GI bleeding or severe anemia with standard of care prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (pre-COVID arm).

Characteristics of the two cohorts were generally similar, although the COVID arm included a slightly older population, with a median age of 68 years, compared with a median age of 61.8 years for the pre-COVID arm (P = .03). Among presenting symptoms, hematochezia was less common in the COVID group (4% vs. 18%; P = .03). Comorbidities were not significantly different between cohorts.

Per the study design, 100% of patients in the COVID arm underwent VCE as their first diagnostic modality. In the pre-COVID arm, 82% of patients first underwent upper endoscopy, followed by colonoscopy (12%) and VCE (5%).

The main outcome, bleeding localization, did not differ between groups, whether this was confined to the first test, or in terms of final localization. But VCE was significantly better at detecting active bleeding or stigmata of bleeding, at a rate of 66%, compared with 28% in the pre-COVID group (P < .001). Patients in the COVID arm were also significantly less likely to need any invasive procedures (44% vs. 96%; P < .001).

No intergroup differences were observed in rates of blood transfusion, in-hospital or GI-bleed mortality, rebleeding, or readmission for bleeding.

“VCE appears to be a safe alternative to traditional diagnostic evaluation of GI bleeding in the era of COVID,” Dr. Hakimian concluded, noting that “the VCE-first strategy reduces the risk of staff exposure to endoscopic aerosols, conserves personal protective equipment, and reduces staff utilization.”

According to Neil Sengupta, MD, of the University of Chicago, “a VCE-first strategy in GI bleeding may be a useful triage tool in the COVID-19 era to determine which patients truly benefit from invasive endoscopy,” although he also noted that “further data are needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this approach.”

Lawrence Hookey, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., had a similar opinion.

“VCE appears to be a reasonable alternative in this patient group, at least as a first step,” Dr. Hookey said. “However, whether it truly makes a difference in the decision making process would have to be assessed prospectively via a randomized controlled trial or a decision analysis done in real time at various steps of the patient’s care path.”

Erik A. Holzwanger, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, suggested that these findings may “serve as a foundation” for similar studies, “as it appears COVID-19 will be an ongoing obstacle in endoscopy for the foreseeable future.”

“It would be interesting to have further discussion of timing of VCE, any COVID-19 transmission to staff during the VCE placement, and discussion of what constituted proceeding with endoscopic intervention [high-risk lesion, active bleeding] in both groups,” he added.

David Cave, MD, PhD, coauthor of the present study and the 2015 ACG clinical guideline for small bowel bleeding, said that VCE is gaining ground as the diagnostic of choice for GI bleeding, and patients prefer it, since it does not require anesthesia.

“This abstract is another clear pointer to the way in which, we should in the future, investigate gastrointestinal bleeding, both acute and chronic,” Dr. Cave said. “We are at an inflection point of transition to a new technology.”

Dr. Cave disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Olympus. The other investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers an alternative triage tool for acute GI bleeding that may reduce personnel exposure to SARS-CoV-2, based on a cohort study with historical controls.

VCE should be considered even when rapid coronavirus testing is available, as active bleeding is more likely to be detected when evaluated sooner, potentially sparing patients from invasive procedures, reported lead author Shahrad Hakimian, MD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worchester, and colleagues.

“Endoscopists and staff are at high risk of exposure to coronavirus through aerosols, as well as unintended, unrecognized splashes that are well known to occur frequently during routine endoscopy,” Dr. Hakimian said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although pretesting and delaying procedures as needed may mitigate risks of viral exposure, “many urgent procedures, such as endoscopic evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding, can’t really wait,” Dr. Hakimian said.

Current guidelines recommend early upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy for evaluation of GI bleeding, but Dr. Hakimian noted that two out of three initial tests are nondiagnostic, so multiple procedures are often needed to find an answer.

In 2018, a randomized, controlled trial coauthored by Dr. Hakimian’s colleagues demonstrated how VCE may be a better approach, as it more frequently detected active bleeding than standard of care (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.36-5.64).

The present study built on these findings in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Hakimian and colleagues analyzed data from 50 consecutive, hemodynamically stable patients with severe anemia or suspected GI bleeding who underwent VCE as a first-line diagnostic modality from mid-March to mid-May 2020 (COVID arm). These patients were compared with 57 consecutive patients who were evaluated for acute GI bleeding or severe anemia with standard of care prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (pre-COVID arm).

Characteristics of the two cohorts were generally similar, although the COVID arm included a slightly older population, with a median age of 68 years, compared with a median age of 61.8 years for the pre-COVID arm (P = .03). Among presenting symptoms, hematochezia was less common in the COVID group (4% vs. 18%; P = .03). Comorbidities were not significantly different between cohorts.

Per the study design, 100% of patients in the COVID arm underwent VCE as their first diagnostic modality. In the pre-COVID arm, 82% of patients first underwent upper endoscopy, followed by colonoscopy (12%) and VCE (5%).

The main outcome, bleeding localization, did not differ between groups, whether this was confined to the first test, or in terms of final localization. But VCE was significantly better at detecting active bleeding or stigmata of bleeding, at a rate of 66%, compared with 28% in the pre-COVID group (P < .001). Patients in the COVID arm were also significantly less likely to need any invasive procedures (44% vs. 96%; P < .001).

No intergroup differences were observed in rates of blood transfusion, in-hospital or GI-bleed mortality, rebleeding, or readmission for bleeding.

“VCE appears to be a safe alternative to traditional diagnostic evaluation of GI bleeding in the era of COVID,” Dr. Hakimian concluded, noting that “the VCE-first strategy reduces the risk of staff exposure to endoscopic aerosols, conserves personal protective equipment, and reduces staff utilization.”

According to Neil Sengupta, MD, of the University of Chicago, “a VCE-first strategy in GI bleeding may be a useful triage tool in the COVID-19 era to determine which patients truly benefit from invasive endoscopy,” although he also noted that “further data are needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this approach.”

Lawrence Hookey, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., had a similar opinion.

“VCE appears to be a reasonable alternative in this patient group, at least as a first step,” Dr. Hookey said. “However, whether it truly makes a difference in the decision making process would have to be assessed prospectively via a randomized controlled trial or a decision analysis done in real time at various steps of the patient’s care path.”

Erik A. Holzwanger, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, suggested that these findings may “serve as a foundation” for similar studies, “as it appears COVID-19 will be an ongoing obstacle in endoscopy for the foreseeable future.”

“It would be interesting to have further discussion of timing of VCE, any COVID-19 transmission to staff during the VCE placement, and discussion of what constituted proceeding with endoscopic intervention [high-risk lesion, active bleeding] in both groups,” he added.

David Cave, MD, PhD, coauthor of the present study and the 2015 ACG clinical guideline for small bowel bleeding, said that VCE is gaining ground as the diagnostic of choice for GI bleeding, and patients prefer it, since it does not require anesthesia.

“This abstract is another clear pointer to the way in which, we should in the future, investigate gastrointestinal bleeding, both acute and chronic,” Dr. Cave said. “We are at an inflection point of transition to a new technology.”

Dr. Cave disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Olympus. The other investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers an alternative triage tool for acute GI bleeding that may reduce personnel exposure to SARS-CoV-2, based on a cohort study with historical controls.

VCE should be considered even when rapid coronavirus testing is available, as active bleeding is more likely to be detected when evaluated sooner, potentially sparing patients from invasive procedures, reported lead author Shahrad Hakimian, MD, of the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worchester, and colleagues.

“Endoscopists and staff are at high risk of exposure to coronavirus through aerosols, as well as unintended, unrecognized splashes that are well known to occur frequently during routine endoscopy,” Dr. Hakimian said during a virtual presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although pretesting and delaying procedures as needed may mitigate risks of viral exposure, “many urgent procedures, such as endoscopic evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding, can’t really wait,” Dr. Hakimian said.

Current guidelines recommend early upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy for evaluation of GI bleeding, but Dr. Hakimian noted that two out of three initial tests are nondiagnostic, so multiple procedures are often needed to find an answer.

In 2018, a randomized, controlled trial coauthored by Dr. Hakimian’s colleagues demonstrated how VCE may be a better approach, as it more frequently detected active bleeding than standard of care (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.36-5.64).

The present study built on these findings in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Hakimian and colleagues analyzed data from 50 consecutive, hemodynamically stable patients with severe anemia or suspected GI bleeding who underwent VCE as a first-line diagnostic modality from mid-March to mid-May 2020 (COVID arm). These patients were compared with 57 consecutive patients who were evaluated for acute GI bleeding or severe anemia with standard of care prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (pre-COVID arm).

Characteristics of the two cohorts were generally similar, although the COVID arm included a slightly older population, with a median age of 68 years, compared with a median age of 61.8 years for the pre-COVID arm (P = .03). Among presenting symptoms, hematochezia was less common in the COVID group (4% vs. 18%; P = .03). Comorbidities were not significantly different between cohorts.

Per the study design, 100% of patients in the COVID arm underwent VCE as their first diagnostic modality. In the pre-COVID arm, 82% of patients first underwent upper endoscopy, followed by colonoscopy (12%) and VCE (5%).

The main outcome, bleeding localization, did not differ between groups, whether this was confined to the first test, or in terms of final localization. But VCE was significantly better at detecting active bleeding or stigmata of bleeding, at a rate of 66%, compared with 28% in the pre-COVID group (P < .001). Patients in the COVID arm were also significantly less likely to need any invasive procedures (44% vs. 96%; P < .001).

No intergroup differences were observed in rates of blood transfusion, in-hospital or GI-bleed mortality, rebleeding, or readmission for bleeding.

“VCE appears to be a safe alternative to traditional diagnostic evaluation of GI bleeding in the era of COVID,” Dr. Hakimian concluded, noting that “the VCE-first strategy reduces the risk of staff exposure to endoscopic aerosols, conserves personal protective equipment, and reduces staff utilization.”

According to Neil Sengupta, MD, of the University of Chicago, “a VCE-first strategy in GI bleeding may be a useful triage tool in the COVID-19 era to determine which patients truly benefit from invasive endoscopy,” although he also noted that “further data are needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this approach.”

Lawrence Hookey, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., had a similar opinion.

“VCE appears to be a reasonable alternative in this patient group, at least as a first step,” Dr. Hookey said. “However, whether it truly makes a difference in the decision making process would have to be assessed prospectively via a randomized controlled trial or a decision analysis done in real time at various steps of the patient’s care path.”

Erik A. Holzwanger, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, suggested that these findings may “serve as a foundation” for similar studies, “as it appears COVID-19 will be an ongoing obstacle in endoscopy for the foreseeable future.”

“It would be interesting to have further discussion of timing of VCE, any COVID-19 transmission to staff during the VCE placement, and discussion of what constituted proceeding with endoscopic intervention [high-risk lesion, active bleeding] in both groups,” he added.

David Cave, MD, PhD, coauthor of the present study and the 2015 ACG clinical guideline for small bowel bleeding, said that VCE is gaining ground as the diagnostic of choice for GI bleeding, and patients prefer it, since it does not require anesthesia.

“This abstract is another clear pointer to the way in which, we should in the future, investigate gastrointestinal bleeding, both acute and chronic,” Dr. Cave said. “We are at an inflection point of transition to a new technology.”

Dr. Cave disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Olympus. The other investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM ACG 2020