User login

Mock scorecards, interactive blueprints, quality dashboards: Hospitals are frantically seeking out any advantage that might help them excel in a fast-approaching, mandatory competition with millions of dollars on the line. Value-based purchasing (VBP), a program authorized by the Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act of 2010, gives the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) the power to base a portion of hospital reimbursement payments on how well hospitals perform in 25 core measures.

The move is intended to help CMS flex its muscles and move from being a passive bystander to an active buyer of what its officials have deemed higher-quality healthcare. Analysts and healthcare experts warn that if hospitalists aren’t paying attention, however, they could put themselves at unnecessary risk or lose out on a major opportunity to demonstrate their value in what Patrick Torcson, MD, SFHM, is calling a “team sport.”

Dr. Torcson, chair of SHM’s Performance and Standards Committee, says every hospitalist should be aware of the core-measures concept, which has been around since 2003 in what’s now called the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program. “We’re not reinventing the wheel; we’re just transforming the program from pay-for-reporting to actual pay-for-performance,” he says. Value-based purchasing, though, is raising the stakes considerably. “It’s really significant because it marks the beginning of an era of accountability and true pay-for-performance at the hospital level.”

A major reason for the heightened concern is the structure of the program. In other quality demonstration projects, CMS has established a score to beat: “Anyone above that threshold is in the money. If you didn’t make it, there was no harm, no foul,” says Trent Haywood, MD, JD, chief medical officer of the Irving, Tex.-based for-profit healthcare cooperative VHA Inc.

—Laura Dietzel, PeaceHealth’s program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use

What’s different this time is that value-based purchasing is not a collaboration but a competition in which every hospital is pitted against the entire market, says Dr. Haywood, the former deputy chief medical officer at CMS. It’s also a zero-sum game. That means there will be winners and losers, with the entire cost-neutral program funded by extracting money from the worst performers to financially reward the best. “In this competition-type model, you need to know who you can beat,” he says.

Race to the Top

That new reality has set off a mad scramble among hospitals hoping to gain any edge they can and spawned a cottage industry of consultants, lawyers, and quality specialists advising them on how to maximize their points. The drive to achieve and maintain a high level of performance is also spurring hospitals to seek more individual accountability as they look to minimize their financial risk.

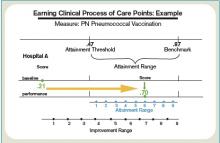

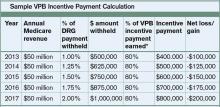

Hospitals’ baseline scores already have been set, and the initial nine-month performance evaluation period begins July 1. Beginning with discharges on Oct. 1, 2012 (fiscal year 2013), the payment phase will kick in. CMS will start by withholding 1% of the base DRG reimbursement paid to hospitals. That money can be earned back based on how well each hospital scores on the performance measures during the evaluation period. The amount initially withheld will rise by 0.25 percentage points per year until it is capped at 2% in 2017 and beyond.

Think of the competition as an annual decathlon with a pool of prize money funded by the participants, except that hospitals will be evaluated on far more measures. So far, the program includes 17 core Clinical Process of Care measures and eight measures based on Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) surveys. Twenty other potential measures are waiting in the wings, including ones related to hospital-acquired conditions, patient safety, inpatient quality, and mortality, some of which likely will be introduced in fiscal year 2014.

CMS intends to monitor and evaluate the program’s impact on access and quality of care, especially for “vulnerable populations,” the percentage of patients who receive appropriate care, the rates of hospital-acquired conditions, and the best practices of high-performing hospitals.

The complicated nature of the rules and scoring, and significant money attached to the competition, have generated deep concern. In October and again in February, healthcare providers bombarded CMS representatives with questions and suggestions during open phone forums, when the regulations were still in flux. Would the rules be fair? Would CMS provide an early warning of impending losses? Was the agency giving too much weight to patient satisfaction scores?

SHM supports the program, stating, “We believe that the Medicare reimbursement system must be changed to promote value, and we strongly support policies that link quality measurement to performance-based payment.”

Other observers, though, have warned of the potential for unintended consequences. If doctors avoid complicated medical cases in order to increase a hospital’s score, for example, are they really improving care? Will poorly performing hospitals get caught in a vicious circle due to declining financial resources?

Some critics have complained that by scoring on a curve rather than on an absolute point system, the value-based purchasing program might not be a quality initiative so much as an opportunity for CMS to reduce hospital payments. “I believe that this is largely a shell game played by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to give hospitals the idea that they can win at this game, when all but a few will lose,” wrote Richard Rohr, MD, FHM, in his Feb. 1 entry at the Medical Staff Leader blog (http://blogs.hcpro.com/medicalstaff/). Hospitalist subsidies could be a prime target as the cost-reduction pressures rise, wrote Dr. Rohr, who directs HM programs for Guthrie Healthcare System in Sayre, Pa. Enhancing productivity, he stressed, could be the best defense against a rollback in salaries.

Most experts agree that investing in a quality infrastructure will be essential for success, though other hospitalists differ on the potential effects that VBP might have on their profession. “I think a big part of a quality infrastructure is a hospital medicine program,” Dr. Torcson says. In fact, he recommends that hospitalists approach a hospital CFO or CEO and offer their assistance with the program. “I really think that’s the right direction and the right attitude, kind of the way the Samurai used to serve the Japanese emperor,” he explains.

A major reason for taking the initiative, he says, is that value-based purchasing could become the new business case for HM. In the 1990s, hospitalists could put a real number on how much they saved hospitals by reducing length of stay, sparking an investment in HM programs. “I think value-based purchasing is now in the same position,” Dr. Torcson says, “and the savings is actually going to be even more quantifiable for the hospital in terms of their success or failure.”

continued below...

Expectations on the Rise

SHM’s annual meeting this month in Grapevine, Texas (www.hospitalmedicine2011.org), will feature a session on improving HCAHPS scores, and Dr. Torcson has been working on a society task force educating members about how to be successful amid the coming changes. A Web-based toolkit in the works, he says, will highlight best practices for myocardial infarctions, heart failure, surgical care, pneumonia, and patient satisfaction to help hospitalists ensure they have the necessary skill sets. (SHM will offer a full platform of VBP courses by end of 2011.)

“At the individual hospitalist level, once you’ve decided to commit to serving that hospital-level performance agenda, we want SHM to be the place to turn to get the information on best practices and what you need,” Dr. Torcson says.

But first, says Bill Darling, a Washington, D.C., and Austin, Tex.-based partner with Strasburger Attorneys at Law, hospitalists will need a much stronger understanding of hospital expectations. Many hospital officials already are indicating that they’re leaning toward their own pay-for-performance programs to put individual doctors on the hook for negative financial incentives and penalties.

“Ultimately, in these value-based systems,” says Darling, a specialist in healthcare contracts and regulations, “the quality scores for physicians may affect their medical staff privileges or their membership in their group, or their ability to even move to another hospital.”

Moreover, hospital administrators are trying to instill a sense of shared responsibility in maintaining high value-based purchasing scores. “I cannot make a physician prescribe an ACE inhibitor when it’s appropriate to deal with heart failure, but the hospital takes a hit for that,” says Dee Rogers, RN, director of quality and risk management at Magnolia Regional Medical Center in Magnolia, Ark. “Not that I want to see people get their hands slapped—I want to see equal accountability.”

Like other hospitals, Rogers’ 49-bed rural facility is tracking doctors’ performance on quality measures and guidelines as part of its credentialing process. Many facilities are starting to include more comprehensive evaluations as part of their contract renegotiations. Magnolia has one weekend hospitalist and is conducting a feasibility study on whether to launch a full-time hospitalist program on weekdays. If the hospital pursues that program, Rogers says, she’d like to see upfront expectations built into the doctors’ contracts.

PeaceHealth, a faith-based nonprofit healthcare system that operates eight hospitals in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska, is moving in the same direction. “I think we’re getting pretty close—certainly within the next year, probably sooner—of creating a reliable mechanism for physician accountability related to the measures that are included in value-based purchasing,” says Laura Dietzel, PeaceHealth’s program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use. That mechanism will connect specific core measures with specific physicians, not just roles or departments.

“We are really honing in on that kind of a quality dashboard, and [VBP’s arrival] is definitely going to be a big boost toward doing that,” says Dietzel, the health system’s former program manager for core measures. “We are talking about making it part of our credentialing process, part of our privileging process, and part of our physician reimbursement and pay schedule process.”

Dietzel concedes that the health system will need to develop a valid method for ensuring that it correctly records who had the responsibility for key decisions. Apart from the concern over proper credit and blame, Darling warns that doctors who haven’t been paying attention could be left holding the bag.

If a hospitalist contract doesn’t discuss how payments will be handled with bundling, value-based purchasing, accountable care, and other models coming down the pike, Darling says, “it may be that you’ve bought a pig in a poke and that you’re just hoping for the kindness of strangers.” Likewise, if a hospital underperforms on its VBP scores due to a lack of investment or training, he asks, will its physicians also look bad on paper? The perceived guilt by association might hurt their chances at finding employment elsewhere if other hospital administrators fear that doctors from poorly performing facilities will hurt their scores as well.

To avoid the most dire “What if?” scenarios, hospitals are enlisting their staff and trying out new tools to help them identify and address trouble spots. At Dr. Torcson’s own hospital, 237-bed St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La., hospitalists and other staff members are scrutinizing the core measures and tweaking guidelines and best practices to make sure the facility is in top form. Based on initial modeling, the hospital expects to earn back all of its withheld reimbursements, though Dr. Torcson says the push is still on to increase the cushion.

A few QI organizations that contract with CMS, including Seattle-based Qualis Health, have developed interactive calculators or mock scorecards to help hospitals determine where they stand in the value-based purchasing scrum. Patricia Richardson, MA, RCP, director of quality and risk for 50-bed Samaritan Hospital in Moses Lake, Wash., says the hospital has worked with Qualis (www.qualishealth.org) on a scorecard to help staff understand which measures need attention and what the financial repercussions would be if the hospital doesn’t improve.

After earlier pushback from doctors on some core measures, quality-review specialist Rebecca Johnson says Samaritan began posting how individual doctors were performing. “And, over time, that motivated them,” she says. “Nobody wants to be the guy in the red.” Johnson says the hospital’s four hospitalists, though, have been fully engaged. “Our hospitalists are very interested in how we’re doing,” she says. “When I’m on the floor doing my reviews, they consistently ask—all of them—‘How are we doing on the core measures?’ ”

Although Richardson concedes that Samaritan still has work to do to increase its patient-satisfaction scores, she’s hopeful that more education and engagement of both patients and staff will begin to pay off. Initiatives that have recruited patients as active participants in helping the hospital improve might help boost patient satisfaction scores, and internal competitions could help motivate the medical staff.

Setting upfront expectations about the hospital stay during the admissions process also can help. Richardson says patients naturally compare a hospital’s noise level to that of their own homes unless a doctor or other staff member provides the proper context. Letting patients know what to expect and reminding them that they’ll likely have to be awakened a few times during the night can make a big difference in whether they rate the hospital as being sufficiently quiet, she says.

Competition Breeds Cooperation

Hospitals likely will be able to differentiate themselves the most through the national competition’s patient perception of care scores, VHA Inc.’s Dr. Haywood says, largely because the contenders have had less time to prepare for them than for the clinical process-of-care measures. Among the eight HCAHPS measures, Dr. Haywood says, focusing on doctor communication, nurse communication, hospital staff responsiveness, and a quiet room might provide the biggest return on investment.

“If physicians don’t communicate effectively with the nurses, then the nurse communication score goes down because the patients assume that the nurses know the care plan,” he says. “A typical question that we see all the time is that the nurse will ask the patient, ‘Did the doctor come and see you today?’ And if the patient says yes, then the nurse will ask, ‘Well, what did the doctor say?’ because the nurse doesn’t know.”

With VBP in mind, Dr. Haywood’s health system repurposed part of its catalogue of Web-based blueprints designed to help hospitals improve their clinical practices (see Figure 2, below). The cooperative is now making its collection of more than 100 blueprints available to its members to help them prop up sagging core measure scores. All depict best-practice solutions in an easy-to-remember visual format, based on weeklong site visits to exemplary hospitals from a clinical team that includes a cultural anthropologist and graphic artist.

Arkansas’ Magnolia already exceeds the national average for every HCAHPS score except the overall rating, a score that will likely increase because most patient evaluations were conducted before a new facility replaced the previous, aging hospital in February 2010. Rogers says Magnolia’s weekend hospitalist has helped with continuity of care—an important factor for maintaining high satisfaction in a small, rural community where doctors tend to see the same elderly patients on a frequent basis. The patients know the hospitalist by name, she says, “so they almost have as much of a relationship to him as they do with their primary-care physician.”

Rogers says the weekend hospitalist also has helped improve some of the hospital’s lagging pneumonia-related scores by educating and communicating with other members of the medical staff about their respective responsibilities. Because he has gained the trust of his peers, Rogers says, he’s helped the hospital get more buy-in from them as well.

Embracing the role of VBP champion, Dr. Torcson says, could help further define the worth of hospitalists to their employers. And with a trend toward more individual physician accountability, rising to the occasion now could help hospitalists stay on top of their own game. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Mock scorecards, interactive blueprints, quality dashboards: Hospitals are frantically seeking out any advantage that might help them excel in a fast-approaching, mandatory competition with millions of dollars on the line. Value-based purchasing (VBP), a program authorized by the Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act of 2010, gives the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) the power to base a portion of hospital reimbursement payments on how well hospitals perform in 25 core measures.

The move is intended to help CMS flex its muscles and move from being a passive bystander to an active buyer of what its officials have deemed higher-quality healthcare. Analysts and healthcare experts warn that if hospitalists aren’t paying attention, however, they could put themselves at unnecessary risk or lose out on a major opportunity to demonstrate their value in what Patrick Torcson, MD, SFHM, is calling a “team sport.”

Dr. Torcson, chair of SHM’s Performance and Standards Committee, says every hospitalist should be aware of the core-measures concept, which has been around since 2003 in what’s now called the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program. “We’re not reinventing the wheel; we’re just transforming the program from pay-for-reporting to actual pay-for-performance,” he says. Value-based purchasing, though, is raising the stakes considerably. “It’s really significant because it marks the beginning of an era of accountability and true pay-for-performance at the hospital level.”

A major reason for the heightened concern is the structure of the program. In other quality demonstration projects, CMS has established a score to beat: “Anyone above that threshold is in the money. If you didn’t make it, there was no harm, no foul,” says Trent Haywood, MD, JD, chief medical officer of the Irving, Tex.-based for-profit healthcare cooperative VHA Inc.

—Laura Dietzel, PeaceHealth’s program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use

What’s different this time is that value-based purchasing is not a collaboration but a competition in which every hospital is pitted against the entire market, says Dr. Haywood, the former deputy chief medical officer at CMS. It’s also a zero-sum game. That means there will be winners and losers, with the entire cost-neutral program funded by extracting money from the worst performers to financially reward the best. “In this competition-type model, you need to know who you can beat,” he says.

Race to the Top

That new reality has set off a mad scramble among hospitals hoping to gain any edge they can and spawned a cottage industry of consultants, lawyers, and quality specialists advising them on how to maximize their points. The drive to achieve and maintain a high level of performance is also spurring hospitals to seek more individual accountability as they look to minimize their financial risk.

Hospitals’ baseline scores already have been set, and the initial nine-month performance evaluation period begins July 1. Beginning with discharges on Oct. 1, 2012 (fiscal year 2013), the payment phase will kick in. CMS will start by withholding 1% of the base DRG reimbursement paid to hospitals. That money can be earned back based on how well each hospital scores on the performance measures during the evaluation period. The amount initially withheld will rise by 0.25 percentage points per year until it is capped at 2% in 2017 and beyond.

Think of the competition as an annual decathlon with a pool of prize money funded by the participants, except that hospitals will be evaluated on far more measures. So far, the program includes 17 core Clinical Process of Care measures and eight measures based on Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) surveys. Twenty other potential measures are waiting in the wings, including ones related to hospital-acquired conditions, patient safety, inpatient quality, and mortality, some of which likely will be introduced in fiscal year 2014.

CMS intends to monitor and evaluate the program’s impact on access and quality of care, especially for “vulnerable populations,” the percentage of patients who receive appropriate care, the rates of hospital-acquired conditions, and the best practices of high-performing hospitals.

The complicated nature of the rules and scoring, and significant money attached to the competition, have generated deep concern. In October and again in February, healthcare providers bombarded CMS representatives with questions and suggestions during open phone forums, when the regulations were still in flux. Would the rules be fair? Would CMS provide an early warning of impending losses? Was the agency giving too much weight to patient satisfaction scores?

SHM supports the program, stating, “We believe that the Medicare reimbursement system must be changed to promote value, and we strongly support policies that link quality measurement to performance-based payment.”

Other observers, though, have warned of the potential for unintended consequences. If doctors avoid complicated medical cases in order to increase a hospital’s score, for example, are they really improving care? Will poorly performing hospitals get caught in a vicious circle due to declining financial resources?

Some critics have complained that by scoring on a curve rather than on an absolute point system, the value-based purchasing program might not be a quality initiative so much as an opportunity for CMS to reduce hospital payments. “I believe that this is largely a shell game played by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to give hospitals the idea that they can win at this game, when all but a few will lose,” wrote Richard Rohr, MD, FHM, in his Feb. 1 entry at the Medical Staff Leader blog (http://blogs.hcpro.com/medicalstaff/). Hospitalist subsidies could be a prime target as the cost-reduction pressures rise, wrote Dr. Rohr, who directs HM programs for Guthrie Healthcare System in Sayre, Pa. Enhancing productivity, he stressed, could be the best defense against a rollback in salaries.

Most experts agree that investing in a quality infrastructure will be essential for success, though other hospitalists differ on the potential effects that VBP might have on their profession. “I think a big part of a quality infrastructure is a hospital medicine program,” Dr. Torcson says. In fact, he recommends that hospitalists approach a hospital CFO or CEO and offer their assistance with the program. “I really think that’s the right direction and the right attitude, kind of the way the Samurai used to serve the Japanese emperor,” he explains.

A major reason for taking the initiative, he says, is that value-based purchasing could become the new business case for HM. In the 1990s, hospitalists could put a real number on how much they saved hospitals by reducing length of stay, sparking an investment in HM programs. “I think value-based purchasing is now in the same position,” Dr. Torcson says, “and the savings is actually going to be even more quantifiable for the hospital in terms of their success or failure.”

continued below...

Expectations on the Rise

SHM’s annual meeting this month in Grapevine, Texas (www.hospitalmedicine2011.org), will feature a session on improving HCAHPS scores, and Dr. Torcson has been working on a society task force educating members about how to be successful amid the coming changes. A Web-based toolkit in the works, he says, will highlight best practices for myocardial infarctions, heart failure, surgical care, pneumonia, and patient satisfaction to help hospitalists ensure they have the necessary skill sets. (SHM will offer a full platform of VBP courses by end of 2011.)

“At the individual hospitalist level, once you’ve decided to commit to serving that hospital-level performance agenda, we want SHM to be the place to turn to get the information on best practices and what you need,” Dr. Torcson says.

But first, says Bill Darling, a Washington, D.C., and Austin, Tex.-based partner with Strasburger Attorneys at Law, hospitalists will need a much stronger understanding of hospital expectations. Many hospital officials already are indicating that they’re leaning toward their own pay-for-performance programs to put individual doctors on the hook for negative financial incentives and penalties.

“Ultimately, in these value-based systems,” says Darling, a specialist in healthcare contracts and regulations, “the quality scores for physicians may affect their medical staff privileges or their membership in their group, or their ability to even move to another hospital.”

Moreover, hospital administrators are trying to instill a sense of shared responsibility in maintaining high value-based purchasing scores. “I cannot make a physician prescribe an ACE inhibitor when it’s appropriate to deal with heart failure, but the hospital takes a hit for that,” says Dee Rogers, RN, director of quality and risk management at Magnolia Regional Medical Center in Magnolia, Ark. “Not that I want to see people get their hands slapped—I want to see equal accountability.”

Like other hospitals, Rogers’ 49-bed rural facility is tracking doctors’ performance on quality measures and guidelines as part of its credentialing process. Many facilities are starting to include more comprehensive evaluations as part of their contract renegotiations. Magnolia has one weekend hospitalist and is conducting a feasibility study on whether to launch a full-time hospitalist program on weekdays. If the hospital pursues that program, Rogers says, she’d like to see upfront expectations built into the doctors’ contracts.

PeaceHealth, a faith-based nonprofit healthcare system that operates eight hospitals in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska, is moving in the same direction. “I think we’re getting pretty close—certainly within the next year, probably sooner—of creating a reliable mechanism for physician accountability related to the measures that are included in value-based purchasing,” says Laura Dietzel, PeaceHealth’s program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use. That mechanism will connect specific core measures with specific physicians, not just roles or departments.

“We are really honing in on that kind of a quality dashboard, and [VBP’s arrival] is definitely going to be a big boost toward doing that,” says Dietzel, the health system’s former program manager for core measures. “We are talking about making it part of our credentialing process, part of our privileging process, and part of our physician reimbursement and pay schedule process.”

Dietzel concedes that the health system will need to develop a valid method for ensuring that it correctly records who had the responsibility for key decisions. Apart from the concern over proper credit and blame, Darling warns that doctors who haven’t been paying attention could be left holding the bag.

If a hospitalist contract doesn’t discuss how payments will be handled with bundling, value-based purchasing, accountable care, and other models coming down the pike, Darling says, “it may be that you’ve bought a pig in a poke and that you’re just hoping for the kindness of strangers.” Likewise, if a hospital underperforms on its VBP scores due to a lack of investment or training, he asks, will its physicians also look bad on paper? The perceived guilt by association might hurt their chances at finding employment elsewhere if other hospital administrators fear that doctors from poorly performing facilities will hurt their scores as well.

To avoid the most dire “What if?” scenarios, hospitals are enlisting their staff and trying out new tools to help them identify and address trouble spots. At Dr. Torcson’s own hospital, 237-bed St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La., hospitalists and other staff members are scrutinizing the core measures and tweaking guidelines and best practices to make sure the facility is in top form. Based on initial modeling, the hospital expects to earn back all of its withheld reimbursements, though Dr. Torcson says the push is still on to increase the cushion.

A few QI organizations that contract with CMS, including Seattle-based Qualis Health, have developed interactive calculators or mock scorecards to help hospitals determine where they stand in the value-based purchasing scrum. Patricia Richardson, MA, RCP, director of quality and risk for 50-bed Samaritan Hospital in Moses Lake, Wash., says the hospital has worked with Qualis (www.qualishealth.org) on a scorecard to help staff understand which measures need attention and what the financial repercussions would be if the hospital doesn’t improve.

After earlier pushback from doctors on some core measures, quality-review specialist Rebecca Johnson says Samaritan began posting how individual doctors were performing. “And, over time, that motivated them,” she says. “Nobody wants to be the guy in the red.” Johnson says the hospital’s four hospitalists, though, have been fully engaged. “Our hospitalists are very interested in how we’re doing,” she says. “When I’m on the floor doing my reviews, they consistently ask—all of them—‘How are we doing on the core measures?’ ”

Although Richardson concedes that Samaritan still has work to do to increase its patient-satisfaction scores, she’s hopeful that more education and engagement of both patients and staff will begin to pay off. Initiatives that have recruited patients as active participants in helping the hospital improve might help boost patient satisfaction scores, and internal competitions could help motivate the medical staff.

Setting upfront expectations about the hospital stay during the admissions process also can help. Richardson says patients naturally compare a hospital’s noise level to that of their own homes unless a doctor or other staff member provides the proper context. Letting patients know what to expect and reminding them that they’ll likely have to be awakened a few times during the night can make a big difference in whether they rate the hospital as being sufficiently quiet, she says.

Competition Breeds Cooperation

Hospitals likely will be able to differentiate themselves the most through the national competition’s patient perception of care scores, VHA Inc.’s Dr. Haywood says, largely because the contenders have had less time to prepare for them than for the clinical process-of-care measures. Among the eight HCAHPS measures, Dr. Haywood says, focusing on doctor communication, nurse communication, hospital staff responsiveness, and a quiet room might provide the biggest return on investment.

“If physicians don’t communicate effectively with the nurses, then the nurse communication score goes down because the patients assume that the nurses know the care plan,” he says. “A typical question that we see all the time is that the nurse will ask the patient, ‘Did the doctor come and see you today?’ And if the patient says yes, then the nurse will ask, ‘Well, what did the doctor say?’ because the nurse doesn’t know.”

With VBP in mind, Dr. Haywood’s health system repurposed part of its catalogue of Web-based blueprints designed to help hospitals improve their clinical practices (see Figure 2, below). The cooperative is now making its collection of more than 100 blueprints available to its members to help them prop up sagging core measure scores. All depict best-practice solutions in an easy-to-remember visual format, based on weeklong site visits to exemplary hospitals from a clinical team that includes a cultural anthropologist and graphic artist.

Arkansas’ Magnolia already exceeds the national average for every HCAHPS score except the overall rating, a score that will likely increase because most patient evaluations were conducted before a new facility replaced the previous, aging hospital in February 2010. Rogers says Magnolia’s weekend hospitalist has helped with continuity of care—an important factor for maintaining high satisfaction in a small, rural community where doctors tend to see the same elderly patients on a frequent basis. The patients know the hospitalist by name, she says, “so they almost have as much of a relationship to him as they do with their primary-care physician.”

Rogers says the weekend hospitalist also has helped improve some of the hospital’s lagging pneumonia-related scores by educating and communicating with other members of the medical staff about their respective responsibilities. Because he has gained the trust of his peers, Rogers says, he’s helped the hospital get more buy-in from them as well.

Embracing the role of VBP champion, Dr. Torcson says, could help further define the worth of hospitalists to their employers. And with a trend toward more individual physician accountability, rising to the occasion now could help hospitalists stay on top of their own game. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Mock scorecards, interactive blueprints, quality dashboards: Hospitals are frantically seeking out any advantage that might help them excel in a fast-approaching, mandatory competition with millions of dollars on the line. Value-based purchasing (VBP), a program authorized by the Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act of 2010, gives the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) the power to base a portion of hospital reimbursement payments on how well hospitals perform in 25 core measures.

The move is intended to help CMS flex its muscles and move from being a passive bystander to an active buyer of what its officials have deemed higher-quality healthcare. Analysts and healthcare experts warn that if hospitalists aren’t paying attention, however, they could put themselves at unnecessary risk or lose out on a major opportunity to demonstrate their value in what Patrick Torcson, MD, SFHM, is calling a “team sport.”

Dr. Torcson, chair of SHM’s Performance and Standards Committee, says every hospitalist should be aware of the core-measures concept, which has been around since 2003 in what’s now called the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program. “We’re not reinventing the wheel; we’re just transforming the program from pay-for-reporting to actual pay-for-performance,” he says. Value-based purchasing, though, is raising the stakes considerably. “It’s really significant because it marks the beginning of an era of accountability and true pay-for-performance at the hospital level.”

A major reason for the heightened concern is the structure of the program. In other quality demonstration projects, CMS has established a score to beat: “Anyone above that threshold is in the money. If you didn’t make it, there was no harm, no foul,” says Trent Haywood, MD, JD, chief medical officer of the Irving, Tex.-based for-profit healthcare cooperative VHA Inc.

—Laura Dietzel, PeaceHealth’s program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use

What’s different this time is that value-based purchasing is not a collaboration but a competition in which every hospital is pitted against the entire market, says Dr. Haywood, the former deputy chief medical officer at CMS. It’s also a zero-sum game. That means there will be winners and losers, with the entire cost-neutral program funded by extracting money from the worst performers to financially reward the best. “In this competition-type model, you need to know who you can beat,” he says.

Race to the Top

That new reality has set off a mad scramble among hospitals hoping to gain any edge they can and spawned a cottage industry of consultants, lawyers, and quality specialists advising them on how to maximize their points. The drive to achieve and maintain a high level of performance is also spurring hospitals to seek more individual accountability as they look to minimize their financial risk.

Hospitals’ baseline scores already have been set, and the initial nine-month performance evaluation period begins July 1. Beginning with discharges on Oct. 1, 2012 (fiscal year 2013), the payment phase will kick in. CMS will start by withholding 1% of the base DRG reimbursement paid to hospitals. That money can be earned back based on how well each hospital scores on the performance measures during the evaluation period. The amount initially withheld will rise by 0.25 percentage points per year until it is capped at 2% in 2017 and beyond.

Think of the competition as an annual decathlon with a pool of prize money funded by the participants, except that hospitals will be evaluated on far more measures. So far, the program includes 17 core Clinical Process of Care measures and eight measures based on Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) surveys. Twenty other potential measures are waiting in the wings, including ones related to hospital-acquired conditions, patient safety, inpatient quality, and mortality, some of which likely will be introduced in fiscal year 2014.

CMS intends to monitor and evaluate the program’s impact on access and quality of care, especially for “vulnerable populations,” the percentage of patients who receive appropriate care, the rates of hospital-acquired conditions, and the best practices of high-performing hospitals.

The complicated nature of the rules and scoring, and significant money attached to the competition, have generated deep concern. In October and again in February, healthcare providers bombarded CMS representatives with questions and suggestions during open phone forums, when the regulations were still in flux. Would the rules be fair? Would CMS provide an early warning of impending losses? Was the agency giving too much weight to patient satisfaction scores?

SHM supports the program, stating, “We believe that the Medicare reimbursement system must be changed to promote value, and we strongly support policies that link quality measurement to performance-based payment.”

Other observers, though, have warned of the potential for unintended consequences. If doctors avoid complicated medical cases in order to increase a hospital’s score, for example, are they really improving care? Will poorly performing hospitals get caught in a vicious circle due to declining financial resources?

Some critics have complained that by scoring on a curve rather than on an absolute point system, the value-based purchasing program might not be a quality initiative so much as an opportunity for CMS to reduce hospital payments. “I believe that this is largely a shell game played by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to give hospitals the idea that they can win at this game, when all but a few will lose,” wrote Richard Rohr, MD, FHM, in his Feb. 1 entry at the Medical Staff Leader blog (http://blogs.hcpro.com/medicalstaff/). Hospitalist subsidies could be a prime target as the cost-reduction pressures rise, wrote Dr. Rohr, who directs HM programs for Guthrie Healthcare System in Sayre, Pa. Enhancing productivity, he stressed, could be the best defense against a rollback in salaries.

Most experts agree that investing in a quality infrastructure will be essential for success, though other hospitalists differ on the potential effects that VBP might have on their profession. “I think a big part of a quality infrastructure is a hospital medicine program,” Dr. Torcson says. In fact, he recommends that hospitalists approach a hospital CFO or CEO and offer their assistance with the program. “I really think that’s the right direction and the right attitude, kind of the way the Samurai used to serve the Japanese emperor,” he explains.

A major reason for taking the initiative, he says, is that value-based purchasing could become the new business case for HM. In the 1990s, hospitalists could put a real number on how much they saved hospitals by reducing length of stay, sparking an investment in HM programs. “I think value-based purchasing is now in the same position,” Dr. Torcson says, “and the savings is actually going to be even more quantifiable for the hospital in terms of their success or failure.”

continued below...

Expectations on the Rise

SHM’s annual meeting this month in Grapevine, Texas (www.hospitalmedicine2011.org), will feature a session on improving HCAHPS scores, and Dr. Torcson has been working on a society task force educating members about how to be successful amid the coming changes. A Web-based toolkit in the works, he says, will highlight best practices for myocardial infarctions, heart failure, surgical care, pneumonia, and patient satisfaction to help hospitalists ensure they have the necessary skill sets. (SHM will offer a full platform of VBP courses by end of 2011.)

“At the individual hospitalist level, once you’ve decided to commit to serving that hospital-level performance agenda, we want SHM to be the place to turn to get the information on best practices and what you need,” Dr. Torcson says.

But first, says Bill Darling, a Washington, D.C., and Austin, Tex.-based partner with Strasburger Attorneys at Law, hospitalists will need a much stronger understanding of hospital expectations. Many hospital officials already are indicating that they’re leaning toward their own pay-for-performance programs to put individual doctors on the hook for negative financial incentives and penalties.

“Ultimately, in these value-based systems,” says Darling, a specialist in healthcare contracts and regulations, “the quality scores for physicians may affect their medical staff privileges or their membership in their group, or their ability to even move to another hospital.”

Moreover, hospital administrators are trying to instill a sense of shared responsibility in maintaining high value-based purchasing scores. “I cannot make a physician prescribe an ACE inhibitor when it’s appropriate to deal with heart failure, but the hospital takes a hit for that,” says Dee Rogers, RN, director of quality and risk management at Magnolia Regional Medical Center in Magnolia, Ark. “Not that I want to see people get their hands slapped—I want to see equal accountability.”

Like other hospitals, Rogers’ 49-bed rural facility is tracking doctors’ performance on quality measures and guidelines as part of its credentialing process. Many facilities are starting to include more comprehensive evaluations as part of their contract renegotiations. Magnolia has one weekend hospitalist and is conducting a feasibility study on whether to launch a full-time hospitalist program on weekdays. If the hospital pursues that program, Rogers says, she’d like to see upfront expectations built into the doctors’ contracts.

PeaceHealth, a faith-based nonprofit healthcare system that operates eight hospitals in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska, is moving in the same direction. “I think we’re getting pretty close—certainly within the next year, probably sooner—of creating a reliable mechanism for physician accountability related to the measures that are included in value-based purchasing,” says Laura Dietzel, PeaceHealth’s program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use. That mechanism will connect specific core measures with specific physicians, not just roles or departments.

“We are really honing in on that kind of a quality dashboard, and [VBP’s arrival] is definitely going to be a big boost toward doing that,” says Dietzel, the health system’s former program manager for core measures. “We are talking about making it part of our credentialing process, part of our privileging process, and part of our physician reimbursement and pay schedule process.”

Dietzel concedes that the health system will need to develop a valid method for ensuring that it correctly records who had the responsibility for key decisions. Apart from the concern over proper credit and blame, Darling warns that doctors who haven’t been paying attention could be left holding the bag.

If a hospitalist contract doesn’t discuss how payments will be handled with bundling, value-based purchasing, accountable care, and other models coming down the pike, Darling says, “it may be that you’ve bought a pig in a poke and that you’re just hoping for the kindness of strangers.” Likewise, if a hospital underperforms on its VBP scores due to a lack of investment or training, he asks, will its physicians also look bad on paper? The perceived guilt by association might hurt their chances at finding employment elsewhere if other hospital administrators fear that doctors from poorly performing facilities will hurt their scores as well.

To avoid the most dire “What if?” scenarios, hospitals are enlisting their staff and trying out new tools to help them identify and address trouble spots. At Dr. Torcson’s own hospital, 237-bed St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La., hospitalists and other staff members are scrutinizing the core measures and tweaking guidelines and best practices to make sure the facility is in top form. Based on initial modeling, the hospital expects to earn back all of its withheld reimbursements, though Dr. Torcson says the push is still on to increase the cushion.

A few QI organizations that contract with CMS, including Seattle-based Qualis Health, have developed interactive calculators or mock scorecards to help hospitals determine where they stand in the value-based purchasing scrum. Patricia Richardson, MA, RCP, director of quality and risk for 50-bed Samaritan Hospital in Moses Lake, Wash., says the hospital has worked with Qualis (www.qualishealth.org) on a scorecard to help staff understand which measures need attention and what the financial repercussions would be if the hospital doesn’t improve.

After earlier pushback from doctors on some core measures, quality-review specialist Rebecca Johnson says Samaritan began posting how individual doctors were performing. “And, over time, that motivated them,” she says. “Nobody wants to be the guy in the red.” Johnson says the hospital’s four hospitalists, though, have been fully engaged. “Our hospitalists are very interested in how we’re doing,” she says. “When I’m on the floor doing my reviews, they consistently ask—all of them—‘How are we doing on the core measures?’ ”

Although Richardson concedes that Samaritan still has work to do to increase its patient-satisfaction scores, she’s hopeful that more education and engagement of both patients and staff will begin to pay off. Initiatives that have recruited patients as active participants in helping the hospital improve might help boost patient satisfaction scores, and internal competitions could help motivate the medical staff.

Setting upfront expectations about the hospital stay during the admissions process also can help. Richardson says patients naturally compare a hospital’s noise level to that of their own homes unless a doctor or other staff member provides the proper context. Letting patients know what to expect and reminding them that they’ll likely have to be awakened a few times during the night can make a big difference in whether they rate the hospital as being sufficiently quiet, she says.

Competition Breeds Cooperation

Hospitals likely will be able to differentiate themselves the most through the national competition’s patient perception of care scores, VHA Inc.’s Dr. Haywood says, largely because the contenders have had less time to prepare for them than for the clinical process-of-care measures. Among the eight HCAHPS measures, Dr. Haywood says, focusing on doctor communication, nurse communication, hospital staff responsiveness, and a quiet room might provide the biggest return on investment.

“If physicians don’t communicate effectively with the nurses, then the nurse communication score goes down because the patients assume that the nurses know the care plan,” he says. “A typical question that we see all the time is that the nurse will ask the patient, ‘Did the doctor come and see you today?’ And if the patient says yes, then the nurse will ask, ‘Well, what did the doctor say?’ because the nurse doesn’t know.”

With VBP in mind, Dr. Haywood’s health system repurposed part of its catalogue of Web-based blueprints designed to help hospitals improve their clinical practices (see Figure 2, below). The cooperative is now making its collection of more than 100 blueprints available to its members to help them prop up sagging core measure scores. All depict best-practice solutions in an easy-to-remember visual format, based on weeklong site visits to exemplary hospitals from a clinical team that includes a cultural anthropologist and graphic artist.

Arkansas’ Magnolia already exceeds the national average for every HCAHPS score except the overall rating, a score that will likely increase because most patient evaluations were conducted before a new facility replaced the previous, aging hospital in February 2010. Rogers says Magnolia’s weekend hospitalist has helped with continuity of care—an important factor for maintaining high satisfaction in a small, rural community where doctors tend to see the same elderly patients on a frequent basis. The patients know the hospitalist by name, she says, “so they almost have as much of a relationship to him as they do with their primary-care physician.”

Rogers says the weekend hospitalist also has helped improve some of the hospital’s lagging pneumonia-related scores by educating and communicating with other members of the medical staff about their respective responsibilities. Because he has gained the trust of his peers, Rogers says, he’s helped the hospital get more buy-in from them as well.

Embracing the role of VBP champion, Dr. Torcson says, could help further define the worth of hospitalists to their employers. And with a trend toward more individual physician accountability, rising to the occasion now could help hospitalists stay on top of their own game. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.