User login

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) for severe, treatment-refractory depression has evolved out of both the troubled history of psychosurgery in the middle of the 20th century and the recent promising application of DBS for movement disorders and other neurologic and psychiatric conditions. This review describes the context in which DBS has emerged as an experimental therapy for refractory depression, explains the rationale for targeting stimulation to the ventral capsule/ventral striatum, and reviews promising results of preliminary clinical studies of DBS for depression.

PSYCHOSURGERY: A CLOUDED HISTORICAL BACKDROP

The use of DBS for depression is best understood within the context of the problematic history of neurosurgery for psychiatric conditions (psychosurgery), which dates back to the development of frontal leucotomy (ie, frontal lobotomy) by Egas Moniz and Pedro Lima in 1935. Walter Freeman, an American neurologist and psychiatrist without surgical training, performed the first prefrontal lobotomy in the United States in 1936. In 1945 Freeman pioneered the transorbital (“ice pick”) lobotomy, which accessed the frontal lobes through the eye sockets rather than by holes drilled in the skull. Freeman’s advocacy of lobotomy as an expedient therapy for psychiatric conditions helped fuel the procedure’s midcentury popularity, as more than 20,000 psychosurgery procedures were performed in the United States for various indications between 1936 and 1955.

Although some symptomatic improvement was seen with these psychosurgery procedures, they quickly became controversial because of their adverse effects, which included personality changes, as well as their perceived barbaric nature and their indiscriminate use by some practitioners. Moreover, little systematic research of these procedures was done, with most studies being poorly designed with little attention to long-term outcomes.

By the 1960s psychosurgery was in decline, largely because of the advent of effective psychopharmacology.

FROM BRAIN LESIONING TO BRAIN STIMULATION

Despite this decline, research on neurosurgery for the treatment of psychiatric conditions continued with small-scale studies of procedures involving smaller brain lesions, such as anterior capsulotomy and anterior cingulotomy using radiofrequency lesioning or gamma knife irradiation. Some of these studies demonstrated significant improvements, particularly in patients with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

These results prompted consideration of DBS for treatment of patients with severe psychiatric illness, especially since DBS offered several potential advantages relative to lesioning:

- Reversibility

- The ability to perform double-blind crossover studies

- The ability to vary stimulation sites and parameters.

Briefly, DBS for psychiatric applications involves bilateral implantation of electrodes in the anterior limb of the ventral internal capsule extending into the ventral striatum. Each electrode has four individually programmable contacts. The neurostimulator is placed in a pocket created in the subclavicular area. The leads are connected to each neurostimulator by tunneling under the scalp and the skin of the neck to the pocket, permitting noninvasive adjustment of the electrical stimulation.

EXPERIENCE WITH STIMULATION IN OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER

Greenberg et al reported outcomes of the use of DBS in 26 patients with severe and highly treatment-resistant OCD treated at four collaborating centers from 2000 to 2005.1 The target for stimulation was the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS); this target evolved slightly over the course of the study as it became evident that outcomes were superior with targets that were more posterior. Concomitant pharmacotherapy was permitted throughout the study.

At 3 to 6 months after initiation of chronic DBS, scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, a measure of OCD severity, improved by an average of nearly 50% in these patients with severe refractory disease,1 which is notably better than the 35% improvement often used as the threshold for response in OCD trials. Improvement in mood was a beneficial side effect of DBS in the study, and in patients with comorbid depression, mood improved to a greater degree than did symptoms of anxiety and OCD.

In the wake of the initial release of this study by Greenberg et al (published online in May 2008) and similar findings, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2009 approved DBS for use in refractory OCD under a humanitarian device exemption. Such exemptions are granted to facilitate the development of devices for rare conditions, and the exemption was applicable in light of the rarity of severe, treatment-resistant, disabling OCD.

RATIONALE FOR BRAIN STIMULATION IN DEPRESSION

A large refractory and disabled population

In contrast to OCD, treatment-refractory depression is rather common, as approximately 20% of patients with depression—roughly 4.4 million US patients—have disease that is resistant to the mainstay treatment options of antidepressant medications and psychotherapy.2 The fact that electroconvulsive therapy is performed more than 100,000 times annually in the United States is another testament to how widespread treatment-resistant depression remains. Even if only some of these patients with severely disabling and refractory depression may be candidates for DBS, they represent a considerable potential patient population.

A pathophysiologic role for the VC/VS

The target for stimulation in OCD—the VC/VS—also has a known anatomic and physiologic role in depression, which makes it an appropriate surgical target for treatment of depression as well. Significantly less VS response to positive stimuli has been observed in depressed patients compared with controls.3 Moreover, the subgenual cingulate region is known to be metabolically hyperactive in patients with major depressive disorder, and positron emission tomography studies of OCD patients who underwent DBS of the VC/VS showed a reduction in subgenual cingulate activity over time.4

White matter tracts in the area 25 region adjacent to the subgenual cingulate cortex represent another target for stimulation. In a pilot study by Mayberg et al, DBS electrodes implanted bilaterally in the subgenual cingulate cortices of 6 patients with treatment-resistant depression resulted in sustained remission of depression in 4 patients at 6 months.5 The benefit of stimulation continued for up to 4 weeks after stimulation ended.

MULTICENTER STUDY OF STIMULATION FOR HIGHLY REFRACTORY DEPRESSION

Our team at Cleveland Clinic partnered with colleagues from Brown Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital to build on these pilot study findings and evaluate DBS of the VC/VS in patients with chronic, severe refractory depression in a multicenter investigation. The results from the first 15 patients in this series were published in early 2009;6 results from an additional 2 patients, for a total sample of 17, are now available and summarized below.

Patients and study design

Patients had at least a 5-year history of chronic or recurrent depression that was refractory to at least five courses of medication, an adequate trial of psychotherapy, and at least one trial of bilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Exclusion criteria included significant substance abuse, severe personality disorder that could potentially affect safety or compliance, and psychotic depression.

Outcome measures included the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and the Global Assessment of Function Scale (GAF). Assessments were performed at baseline, postoperatively, and monthly thereafter. A detailed neuropsychological battery was performed at baseline and again at 6 months.

At the time of electrode implantation, mean patient age was 46.3 years and mean duration of illness was 21.0 years. In their current depressive episode, patients had had an average of 6.1 antidepressant trials and 6.1 trials of augmentation or combination of antidepressant medications. The average number of lifetime electroconvulsive therapy treatments was 30.5; of the 17 patients, 15 had an adequate trial of electroconvulsive therapy in their current depressive episode.

Electrodes were implanted bilaterally in the VC/VS. Following a postoperative recovery phase of 2 to 4 weeks, stimulation parameters were titrated over several days on an outpatient basis. The stimulation parameters were selected on the basis of positive mood benefit and absence of adverse effects. Stimulation was at a frequency of 100 to 130 Hz and an amplitude of 2.5 to 8 V. These stimulation amplitudes are higher than those used for treatment of movement disorders, reflecting the different targets (white matter vs gray matter) for the different conditions.

The two ventral contacts (referred to as contact 0 and contact 1) tend to be the most active, providing the best response. Contact 0 is the most distal contact, at the VS below the level of the anterior commissure. Contact 1 is near the junction of the VS and VC.

The time to battery replacement (due to depletion) ranged from 10 to 18 months.

Outcomes

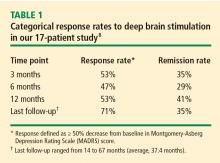

Patients’ mean baseline MADRS score was 34.7, indicating very severe depression. The mean MADRS score improved to 20.6 by 1 month, and declined further to 16.0 at 3 months. This benefit has been maintained to the most recent follow-up (average, 37.4 months; range, 14–67 months). Similar improvements from baseline to most recent follow-up were observed in the HDRS and GAF scores. Additionally, a substantial reduction in suicidality (as measured by mean MADRS suicide subscale score) was observed by 1 month (P = .01) and was maintained through 12 months of follow-up (P < .001).7

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of DBS were observed on occasion and can generally be divided into those related to surgical implantation and those related to stimulation itself.

Effects related to surgical implantation have included infection from lead or battery implantation, adverse cosmetic effects (from placement of the battery-operated neurostimulators into the chest), and repeat surgeries for neurostimulator replacements. A rechargeable battery has recently become available and should enhance tolerability and acceptability by reducing the frequency of replacement surgeries.

Stimulation-induced acute adverse events have included paresthesias, anxiety, mood changes, and autonomic effects. All were reversible with adjustment of stimulation parameters.

DIRECTION AND GUIDANCE FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

A number of recent developments have enhanced the prospects for better understanding of the use of DBS in treatment-refractory depression:

- The recent FDA approval of DBS for severe, refractory OCD should broaden the base of experience with DBS for psychiatric disorders.

- Two large studies of DBS of the VC/VS and the area 25/subgenual cingulate region in depressed patients are currently under way.

- The aforementioned recent development of a rechargeable stimulator battery should improve patient acceptance of DBS therapy.

- Neuroimaging studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography may help to elucidate neuroanatomic pathways in depression and other psychiatric disorders.

- Ongoing studies of DBS for Tourette syndrome will broaden the experience base with DBS and perhaps yield insights for depression.

As investigation of DBS for depression moves forward, it must be conducted in keeping with some basic principles for patient selection and fundamental ethical guidelines, especially in light of the troubled early history of psychosurgery. From the individual patient perspective, patients should be selected only if they meet the following criteria:

- Accurate diagnosis. This may seem obvious, yet inaccurate diagnoses in the psychiatric realm are far more widespread than is appreciated but clearly must be avoided when embarking on an intervention as significant as DBS.

- Ability to provide informed consent

- Sufficient severity of illness

- Nonresponse to less-invasive options (ie, reasonable trials of both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy).

From the ethical and procedural perspective, research of DBS for psychiatric disease must ensure the involvement of expert and dedicated psychiatric neurosurgery teams, led by psychiatrists, as well as full ethical review (by institutional review boards) and method-safety review (in keeping with FDA policy). Additionally, expert centers must be prepared to make the long-term commitment necessary to follow these difficult-to-treat patients. Centers and investigators must also ensure that DBS be used only to alleviate suffering and improve patients’ lives, and never to “augment” normal function or for social or political reasons.9

- Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DA, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Molecular Psychiatry 2010; 15:64–79.

- Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:649–659.

- Epstein J, Pan H, Kocsis JH, et al Lack of ventral striatal response to positive stimuli in depressed versus normal subjects. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1784–1790.

- Rauch SL, Dougherty DD, Malone D, et al A functional neuroimaging investigation of deep brain stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neurosurg 2006; 104:558–565.

- Mayberg LS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 2005; 45:651–660.

- Malone DA, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65:267–275.

- Mathews M, Greenberg B, Dougherty D, et al Change in suicidal ideation in patients undergoing DBS for depression. Presented at: 2008 Biennial Meeting of the American Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery; June 1–4, 2008; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Abstract 124. http://www.assfn.org/project/oral/124.pdf.

- Malone DA, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 16–21, 2009; San Francisco, CA. Abstract NR6-009.

- OCD-DBS Collaborative Group. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. Neurosurgery 2002; 51:519.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) for severe, treatment-refractory depression has evolved out of both the troubled history of psychosurgery in the middle of the 20th century and the recent promising application of DBS for movement disorders and other neurologic and psychiatric conditions. This review describes the context in which DBS has emerged as an experimental therapy for refractory depression, explains the rationale for targeting stimulation to the ventral capsule/ventral striatum, and reviews promising results of preliminary clinical studies of DBS for depression.

PSYCHOSURGERY: A CLOUDED HISTORICAL BACKDROP

The use of DBS for depression is best understood within the context of the problematic history of neurosurgery for psychiatric conditions (psychosurgery), which dates back to the development of frontal leucotomy (ie, frontal lobotomy) by Egas Moniz and Pedro Lima in 1935. Walter Freeman, an American neurologist and psychiatrist without surgical training, performed the first prefrontal lobotomy in the United States in 1936. In 1945 Freeman pioneered the transorbital (“ice pick”) lobotomy, which accessed the frontal lobes through the eye sockets rather than by holes drilled in the skull. Freeman’s advocacy of lobotomy as an expedient therapy for psychiatric conditions helped fuel the procedure’s midcentury popularity, as more than 20,000 psychosurgery procedures were performed in the United States for various indications between 1936 and 1955.

Although some symptomatic improvement was seen with these psychosurgery procedures, they quickly became controversial because of their adverse effects, which included personality changes, as well as their perceived barbaric nature and their indiscriminate use by some practitioners. Moreover, little systematic research of these procedures was done, with most studies being poorly designed with little attention to long-term outcomes.

By the 1960s psychosurgery was in decline, largely because of the advent of effective psychopharmacology.

FROM BRAIN LESIONING TO BRAIN STIMULATION

Despite this decline, research on neurosurgery for the treatment of psychiatric conditions continued with small-scale studies of procedures involving smaller brain lesions, such as anterior capsulotomy and anterior cingulotomy using radiofrequency lesioning or gamma knife irradiation. Some of these studies demonstrated significant improvements, particularly in patients with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

These results prompted consideration of DBS for treatment of patients with severe psychiatric illness, especially since DBS offered several potential advantages relative to lesioning:

- Reversibility

- The ability to perform double-blind crossover studies

- The ability to vary stimulation sites and parameters.

Briefly, DBS for psychiatric applications involves bilateral implantation of electrodes in the anterior limb of the ventral internal capsule extending into the ventral striatum. Each electrode has four individually programmable contacts. The neurostimulator is placed in a pocket created in the subclavicular area. The leads are connected to each neurostimulator by tunneling under the scalp and the skin of the neck to the pocket, permitting noninvasive adjustment of the electrical stimulation.

EXPERIENCE WITH STIMULATION IN OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER

Greenberg et al reported outcomes of the use of DBS in 26 patients with severe and highly treatment-resistant OCD treated at four collaborating centers from 2000 to 2005.1 The target for stimulation was the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS); this target evolved slightly over the course of the study as it became evident that outcomes were superior with targets that were more posterior. Concomitant pharmacotherapy was permitted throughout the study.

At 3 to 6 months after initiation of chronic DBS, scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, a measure of OCD severity, improved by an average of nearly 50% in these patients with severe refractory disease,1 which is notably better than the 35% improvement often used as the threshold for response in OCD trials. Improvement in mood was a beneficial side effect of DBS in the study, and in patients with comorbid depression, mood improved to a greater degree than did symptoms of anxiety and OCD.

In the wake of the initial release of this study by Greenberg et al (published online in May 2008) and similar findings, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2009 approved DBS for use in refractory OCD under a humanitarian device exemption. Such exemptions are granted to facilitate the development of devices for rare conditions, and the exemption was applicable in light of the rarity of severe, treatment-resistant, disabling OCD.

RATIONALE FOR BRAIN STIMULATION IN DEPRESSION

A large refractory and disabled population

In contrast to OCD, treatment-refractory depression is rather common, as approximately 20% of patients with depression—roughly 4.4 million US patients—have disease that is resistant to the mainstay treatment options of antidepressant medications and psychotherapy.2 The fact that electroconvulsive therapy is performed more than 100,000 times annually in the United States is another testament to how widespread treatment-resistant depression remains. Even if only some of these patients with severely disabling and refractory depression may be candidates for DBS, they represent a considerable potential patient population.

A pathophysiologic role for the VC/VS

The target for stimulation in OCD—the VC/VS—also has a known anatomic and physiologic role in depression, which makes it an appropriate surgical target for treatment of depression as well. Significantly less VS response to positive stimuli has been observed in depressed patients compared with controls.3 Moreover, the subgenual cingulate region is known to be metabolically hyperactive in patients with major depressive disorder, and positron emission tomography studies of OCD patients who underwent DBS of the VC/VS showed a reduction in subgenual cingulate activity over time.4

White matter tracts in the area 25 region adjacent to the subgenual cingulate cortex represent another target for stimulation. In a pilot study by Mayberg et al, DBS electrodes implanted bilaterally in the subgenual cingulate cortices of 6 patients with treatment-resistant depression resulted in sustained remission of depression in 4 patients at 6 months.5 The benefit of stimulation continued for up to 4 weeks after stimulation ended.

MULTICENTER STUDY OF STIMULATION FOR HIGHLY REFRACTORY DEPRESSION

Our team at Cleveland Clinic partnered with colleagues from Brown Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital to build on these pilot study findings and evaluate DBS of the VC/VS in patients with chronic, severe refractory depression in a multicenter investigation. The results from the first 15 patients in this series were published in early 2009;6 results from an additional 2 patients, for a total sample of 17, are now available and summarized below.

Patients and study design

Patients had at least a 5-year history of chronic or recurrent depression that was refractory to at least five courses of medication, an adequate trial of psychotherapy, and at least one trial of bilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Exclusion criteria included significant substance abuse, severe personality disorder that could potentially affect safety or compliance, and psychotic depression.

Outcome measures included the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and the Global Assessment of Function Scale (GAF). Assessments were performed at baseline, postoperatively, and monthly thereafter. A detailed neuropsychological battery was performed at baseline and again at 6 months.

At the time of electrode implantation, mean patient age was 46.3 years and mean duration of illness was 21.0 years. In their current depressive episode, patients had had an average of 6.1 antidepressant trials and 6.1 trials of augmentation or combination of antidepressant medications. The average number of lifetime electroconvulsive therapy treatments was 30.5; of the 17 patients, 15 had an adequate trial of electroconvulsive therapy in their current depressive episode.

Electrodes were implanted bilaterally in the VC/VS. Following a postoperative recovery phase of 2 to 4 weeks, stimulation parameters were titrated over several days on an outpatient basis. The stimulation parameters were selected on the basis of positive mood benefit and absence of adverse effects. Stimulation was at a frequency of 100 to 130 Hz and an amplitude of 2.5 to 8 V. These stimulation amplitudes are higher than those used for treatment of movement disorders, reflecting the different targets (white matter vs gray matter) for the different conditions.

The two ventral contacts (referred to as contact 0 and contact 1) tend to be the most active, providing the best response. Contact 0 is the most distal contact, at the VS below the level of the anterior commissure. Contact 1 is near the junction of the VS and VC.

The time to battery replacement (due to depletion) ranged from 10 to 18 months.

Outcomes

Patients’ mean baseline MADRS score was 34.7, indicating very severe depression. The mean MADRS score improved to 20.6 by 1 month, and declined further to 16.0 at 3 months. This benefit has been maintained to the most recent follow-up (average, 37.4 months; range, 14–67 months). Similar improvements from baseline to most recent follow-up were observed in the HDRS and GAF scores. Additionally, a substantial reduction in suicidality (as measured by mean MADRS suicide subscale score) was observed by 1 month (P = .01) and was maintained through 12 months of follow-up (P < .001).7

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of DBS were observed on occasion and can generally be divided into those related to surgical implantation and those related to stimulation itself.

Effects related to surgical implantation have included infection from lead or battery implantation, adverse cosmetic effects (from placement of the battery-operated neurostimulators into the chest), and repeat surgeries for neurostimulator replacements. A rechargeable battery has recently become available and should enhance tolerability and acceptability by reducing the frequency of replacement surgeries.

Stimulation-induced acute adverse events have included paresthesias, anxiety, mood changes, and autonomic effects. All were reversible with adjustment of stimulation parameters.

DIRECTION AND GUIDANCE FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

A number of recent developments have enhanced the prospects for better understanding of the use of DBS in treatment-refractory depression:

- The recent FDA approval of DBS for severe, refractory OCD should broaden the base of experience with DBS for psychiatric disorders.

- Two large studies of DBS of the VC/VS and the area 25/subgenual cingulate region in depressed patients are currently under way.

- The aforementioned recent development of a rechargeable stimulator battery should improve patient acceptance of DBS therapy.

- Neuroimaging studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography may help to elucidate neuroanatomic pathways in depression and other psychiatric disorders.

- Ongoing studies of DBS for Tourette syndrome will broaden the experience base with DBS and perhaps yield insights for depression.

As investigation of DBS for depression moves forward, it must be conducted in keeping with some basic principles for patient selection and fundamental ethical guidelines, especially in light of the troubled early history of psychosurgery. From the individual patient perspective, patients should be selected only if they meet the following criteria:

- Accurate diagnosis. This may seem obvious, yet inaccurate diagnoses in the psychiatric realm are far more widespread than is appreciated but clearly must be avoided when embarking on an intervention as significant as DBS.

- Ability to provide informed consent

- Sufficient severity of illness

- Nonresponse to less-invasive options (ie, reasonable trials of both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy).

From the ethical and procedural perspective, research of DBS for psychiatric disease must ensure the involvement of expert and dedicated psychiatric neurosurgery teams, led by psychiatrists, as well as full ethical review (by institutional review boards) and method-safety review (in keeping with FDA policy). Additionally, expert centers must be prepared to make the long-term commitment necessary to follow these difficult-to-treat patients. Centers and investigators must also ensure that DBS be used only to alleviate suffering and improve patients’ lives, and never to “augment” normal function or for social or political reasons.9

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) for severe, treatment-refractory depression has evolved out of both the troubled history of psychosurgery in the middle of the 20th century and the recent promising application of DBS for movement disorders and other neurologic and psychiatric conditions. This review describes the context in which DBS has emerged as an experimental therapy for refractory depression, explains the rationale for targeting stimulation to the ventral capsule/ventral striatum, and reviews promising results of preliminary clinical studies of DBS for depression.

PSYCHOSURGERY: A CLOUDED HISTORICAL BACKDROP

The use of DBS for depression is best understood within the context of the problematic history of neurosurgery for psychiatric conditions (psychosurgery), which dates back to the development of frontal leucotomy (ie, frontal lobotomy) by Egas Moniz and Pedro Lima in 1935. Walter Freeman, an American neurologist and psychiatrist without surgical training, performed the first prefrontal lobotomy in the United States in 1936. In 1945 Freeman pioneered the transorbital (“ice pick”) lobotomy, which accessed the frontal lobes through the eye sockets rather than by holes drilled in the skull. Freeman’s advocacy of lobotomy as an expedient therapy for psychiatric conditions helped fuel the procedure’s midcentury popularity, as more than 20,000 psychosurgery procedures were performed in the United States for various indications between 1936 and 1955.

Although some symptomatic improvement was seen with these psychosurgery procedures, they quickly became controversial because of their adverse effects, which included personality changes, as well as their perceived barbaric nature and their indiscriminate use by some practitioners. Moreover, little systematic research of these procedures was done, with most studies being poorly designed with little attention to long-term outcomes.

By the 1960s psychosurgery was in decline, largely because of the advent of effective psychopharmacology.

FROM BRAIN LESIONING TO BRAIN STIMULATION

Despite this decline, research on neurosurgery for the treatment of psychiatric conditions continued with small-scale studies of procedures involving smaller brain lesions, such as anterior capsulotomy and anterior cingulotomy using radiofrequency lesioning or gamma knife irradiation. Some of these studies demonstrated significant improvements, particularly in patients with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

These results prompted consideration of DBS for treatment of patients with severe psychiatric illness, especially since DBS offered several potential advantages relative to lesioning:

- Reversibility

- The ability to perform double-blind crossover studies

- The ability to vary stimulation sites and parameters.

Briefly, DBS for psychiatric applications involves bilateral implantation of electrodes in the anterior limb of the ventral internal capsule extending into the ventral striatum. Each electrode has four individually programmable contacts. The neurostimulator is placed in a pocket created in the subclavicular area. The leads are connected to each neurostimulator by tunneling under the scalp and the skin of the neck to the pocket, permitting noninvasive adjustment of the electrical stimulation.

EXPERIENCE WITH STIMULATION IN OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER

Greenberg et al reported outcomes of the use of DBS in 26 patients with severe and highly treatment-resistant OCD treated at four collaborating centers from 2000 to 2005.1 The target for stimulation was the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS); this target evolved slightly over the course of the study as it became evident that outcomes were superior with targets that were more posterior. Concomitant pharmacotherapy was permitted throughout the study.

At 3 to 6 months after initiation of chronic DBS, scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, a measure of OCD severity, improved by an average of nearly 50% in these patients with severe refractory disease,1 which is notably better than the 35% improvement often used as the threshold for response in OCD trials. Improvement in mood was a beneficial side effect of DBS in the study, and in patients with comorbid depression, mood improved to a greater degree than did symptoms of anxiety and OCD.

In the wake of the initial release of this study by Greenberg et al (published online in May 2008) and similar findings, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2009 approved DBS for use in refractory OCD under a humanitarian device exemption. Such exemptions are granted to facilitate the development of devices for rare conditions, and the exemption was applicable in light of the rarity of severe, treatment-resistant, disabling OCD.

RATIONALE FOR BRAIN STIMULATION IN DEPRESSION

A large refractory and disabled population

In contrast to OCD, treatment-refractory depression is rather common, as approximately 20% of patients with depression—roughly 4.4 million US patients—have disease that is resistant to the mainstay treatment options of antidepressant medications and psychotherapy.2 The fact that electroconvulsive therapy is performed more than 100,000 times annually in the United States is another testament to how widespread treatment-resistant depression remains. Even if only some of these patients with severely disabling and refractory depression may be candidates for DBS, they represent a considerable potential patient population.

A pathophysiologic role for the VC/VS

The target for stimulation in OCD—the VC/VS—also has a known anatomic and physiologic role in depression, which makes it an appropriate surgical target for treatment of depression as well. Significantly less VS response to positive stimuli has been observed in depressed patients compared with controls.3 Moreover, the subgenual cingulate region is known to be metabolically hyperactive in patients with major depressive disorder, and positron emission tomography studies of OCD patients who underwent DBS of the VC/VS showed a reduction in subgenual cingulate activity over time.4

White matter tracts in the area 25 region adjacent to the subgenual cingulate cortex represent another target for stimulation. In a pilot study by Mayberg et al, DBS electrodes implanted bilaterally in the subgenual cingulate cortices of 6 patients with treatment-resistant depression resulted in sustained remission of depression in 4 patients at 6 months.5 The benefit of stimulation continued for up to 4 weeks after stimulation ended.

MULTICENTER STUDY OF STIMULATION FOR HIGHLY REFRACTORY DEPRESSION

Our team at Cleveland Clinic partnered with colleagues from Brown Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital to build on these pilot study findings and evaluate DBS of the VC/VS in patients with chronic, severe refractory depression in a multicenter investigation. The results from the first 15 patients in this series were published in early 2009;6 results from an additional 2 patients, for a total sample of 17, are now available and summarized below.

Patients and study design

Patients had at least a 5-year history of chronic or recurrent depression that was refractory to at least five courses of medication, an adequate trial of psychotherapy, and at least one trial of bilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Exclusion criteria included significant substance abuse, severe personality disorder that could potentially affect safety or compliance, and psychotic depression.

Outcome measures included the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and the Global Assessment of Function Scale (GAF). Assessments were performed at baseline, postoperatively, and monthly thereafter. A detailed neuropsychological battery was performed at baseline and again at 6 months.

At the time of electrode implantation, mean patient age was 46.3 years and mean duration of illness was 21.0 years. In their current depressive episode, patients had had an average of 6.1 antidepressant trials and 6.1 trials of augmentation or combination of antidepressant medications. The average number of lifetime electroconvulsive therapy treatments was 30.5; of the 17 patients, 15 had an adequate trial of electroconvulsive therapy in their current depressive episode.

Electrodes were implanted bilaterally in the VC/VS. Following a postoperative recovery phase of 2 to 4 weeks, stimulation parameters were titrated over several days on an outpatient basis. The stimulation parameters were selected on the basis of positive mood benefit and absence of adverse effects. Stimulation was at a frequency of 100 to 130 Hz and an amplitude of 2.5 to 8 V. These stimulation amplitudes are higher than those used for treatment of movement disorders, reflecting the different targets (white matter vs gray matter) for the different conditions.

The two ventral contacts (referred to as contact 0 and contact 1) tend to be the most active, providing the best response. Contact 0 is the most distal contact, at the VS below the level of the anterior commissure. Contact 1 is near the junction of the VS and VC.

The time to battery replacement (due to depletion) ranged from 10 to 18 months.

Outcomes

Patients’ mean baseline MADRS score was 34.7, indicating very severe depression. The mean MADRS score improved to 20.6 by 1 month, and declined further to 16.0 at 3 months. This benefit has been maintained to the most recent follow-up (average, 37.4 months; range, 14–67 months). Similar improvements from baseline to most recent follow-up were observed in the HDRS and GAF scores. Additionally, a substantial reduction in suicidality (as measured by mean MADRS suicide subscale score) was observed by 1 month (P = .01) and was maintained through 12 months of follow-up (P < .001).7

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of DBS were observed on occasion and can generally be divided into those related to surgical implantation and those related to stimulation itself.

Effects related to surgical implantation have included infection from lead or battery implantation, adverse cosmetic effects (from placement of the battery-operated neurostimulators into the chest), and repeat surgeries for neurostimulator replacements. A rechargeable battery has recently become available and should enhance tolerability and acceptability by reducing the frequency of replacement surgeries.

Stimulation-induced acute adverse events have included paresthesias, anxiety, mood changes, and autonomic effects. All were reversible with adjustment of stimulation parameters.

DIRECTION AND GUIDANCE FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

A number of recent developments have enhanced the prospects for better understanding of the use of DBS in treatment-refractory depression:

- The recent FDA approval of DBS for severe, refractory OCD should broaden the base of experience with DBS for psychiatric disorders.

- Two large studies of DBS of the VC/VS and the area 25/subgenual cingulate region in depressed patients are currently under way.

- The aforementioned recent development of a rechargeable stimulator battery should improve patient acceptance of DBS therapy.

- Neuroimaging studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography may help to elucidate neuroanatomic pathways in depression and other psychiatric disorders.

- Ongoing studies of DBS for Tourette syndrome will broaden the experience base with DBS and perhaps yield insights for depression.

As investigation of DBS for depression moves forward, it must be conducted in keeping with some basic principles for patient selection and fundamental ethical guidelines, especially in light of the troubled early history of psychosurgery. From the individual patient perspective, patients should be selected only if they meet the following criteria:

- Accurate diagnosis. This may seem obvious, yet inaccurate diagnoses in the psychiatric realm are far more widespread than is appreciated but clearly must be avoided when embarking on an intervention as significant as DBS.

- Ability to provide informed consent

- Sufficient severity of illness

- Nonresponse to less-invasive options (ie, reasonable trials of both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy).

From the ethical and procedural perspective, research of DBS for psychiatric disease must ensure the involvement of expert and dedicated psychiatric neurosurgery teams, led by psychiatrists, as well as full ethical review (by institutional review boards) and method-safety review (in keeping with FDA policy). Additionally, expert centers must be prepared to make the long-term commitment necessary to follow these difficult-to-treat patients. Centers and investigators must also ensure that DBS be used only to alleviate suffering and improve patients’ lives, and never to “augment” normal function or for social or political reasons.9

- Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DA, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Molecular Psychiatry 2010; 15:64–79.

- Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:649–659.

- Epstein J, Pan H, Kocsis JH, et al Lack of ventral striatal response to positive stimuli in depressed versus normal subjects. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1784–1790.

- Rauch SL, Dougherty DD, Malone D, et al A functional neuroimaging investigation of deep brain stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neurosurg 2006; 104:558–565.

- Mayberg LS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 2005; 45:651–660.

- Malone DA, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65:267–275.

- Mathews M, Greenberg B, Dougherty D, et al Change in suicidal ideation in patients undergoing DBS for depression. Presented at: 2008 Biennial Meeting of the American Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery; June 1–4, 2008; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Abstract 124. http://www.assfn.org/project/oral/124.pdf.

- Malone DA, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 16–21, 2009; San Francisco, CA. Abstract NR6-009.

- OCD-DBS Collaborative Group. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. Neurosurgery 2002; 51:519.

- Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DA, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Molecular Psychiatry 2010; 15:64–79.

- Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:649–659.

- Epstein J, Pan H, Kocsis JH, et al Lack of ventral striatal response to positive stimuli in depressed versus normal subjects. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1784–1790.

- Rauch SL, Dougherty DD, Malone D, et al A functional neuroimaging investigation of deep brain stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neurosurg 2006; 104:558–565.

- Mayberg LS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 2005; 45:651–660.

- Malone DA, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65:267–275.

- Mathews M, Greenberg B, Dougherty D, et al Change in suicidal ideation in patients undergoing DBS for depression. Presented at: 2008 Biennial Meeting of the American Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery; June 1–4, 2008; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Abstract 124. http://www.assfn.org/project/oral/124.pdf.

- Malone DA, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 16–21, 2009; San Francisco, CA. Abstract NR6-009.

- OCD-DBS Collaborative Group. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. Neurosurgery 2002; 51:519.