User login

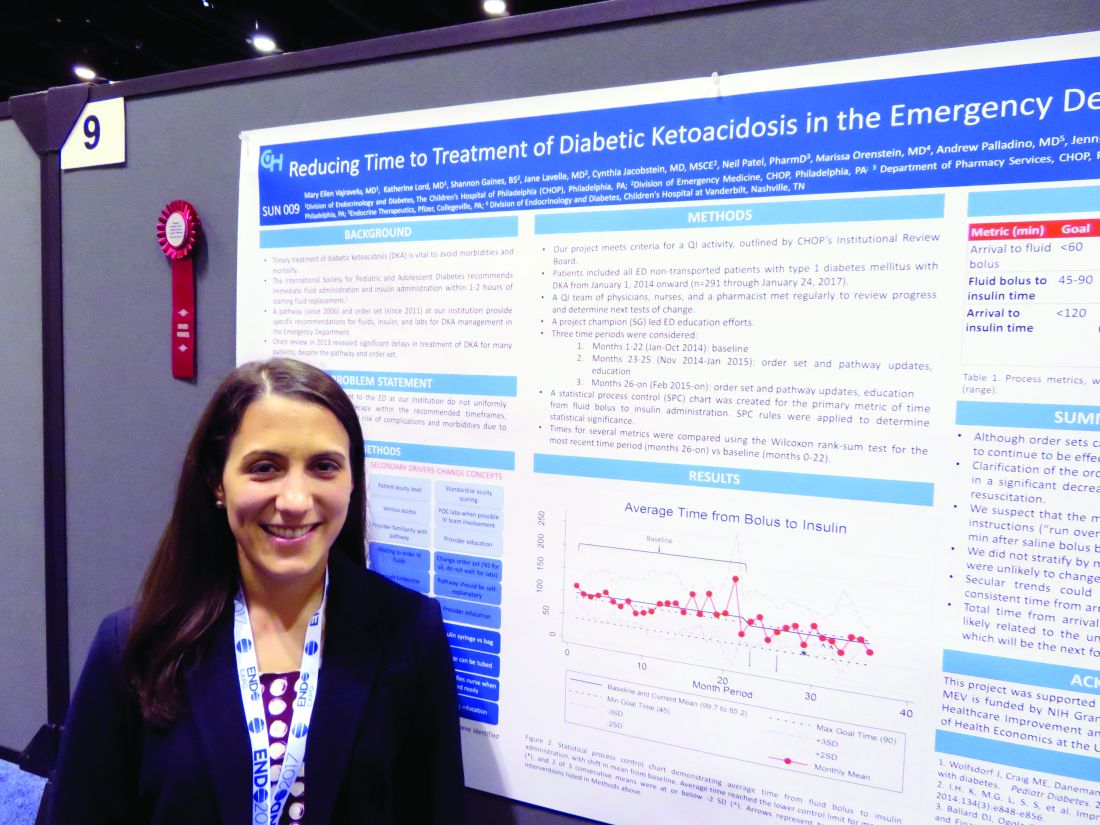

ORLANDO – A few simple adjustments in standing orders shaved 20 minutes off the time one emergency department took to deliver insulin to pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, according to Mary Ellen Vajravelu, MD.

Door-to-insulin time decreased from a mean of 168 minutes to 146 minutes after the changes went into effect. Most of the time was saved in the period between starting the initial fluid bolus and starting the insulin, she said during an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

A single patient’s experience inspired the quality improvement project.

“A couple of years ago, we saw a patient in the emergency department with diabetic ketoacidosis who had to wait more than 6 hours before insulin was started,” she explained. “Fortunately, there were no adverse clinical outcomes from that,” but the case signaled that the treatment process needed some streamlining.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes recommends immediate fluid administration and insulin within 1-2 hours of starting fluid replacement.

The hospital had been following in-house recommendations for fluids, insulin, and labs for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis that were established in 2006 and 2011. When they examined a baseline cohort of patients treated from January to October 2014, they immediately saw that those order sets were not achieving the recommended times.

“We went back and looked at our cases and saw that overall, it was taking more than 2 hours from the time of arrival for these patients to get their insulin,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

She and her colleagues formed a quality improvement team consisting of physicians, nurses, and a pharmacist. They broke down the wait time into three components: arrival to fluid bolus, fluid bolus start to insulin start, and the overall arrival-to-insulin time. They then set specific time goals for each of those periods: giving fluids within 60 minutes of arrival, starting insulin 45-90 minutes from the bolus, and an overall door-to-insulin time of less than 120 minutes.

The team tried to determine key clinical drivers that were affecting these times. One of the first findings was a delay in diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). This was driven by lack of consistency in scoring patient acuity and problems with venous access.

“To address this, we standardized acuity scoring, got an IV team involved, and used point-of-care labs when possible, and educated our providers,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

The team also found that there were delays in ordering the insulin. These were driven by long wait times for intravenous fluids, by waiting for endocrinology consults, and by providers not being familiar with the DKA order sets.

To address these issues, the team changed the order set to use normal saline for all suspected DKA patients without waiting for lab results. The old orders called for delivering the fluid over a 1-hour period; that was changed to running it over 30 minutes, Dr. Vajravelu said. “That shaved off half an hour right there.”

The team examined reasons that insulin infusion was delayed. Pharmacy orders were a big part of this problem, one of which was the way the insulin was sent up from the pharmacy in a bag. “We changed that to being delivered in a syringe and tube system,” she explained.

They also changed the standing order for when insulin was started, from 60 minutes after fluid to 45 minutes.

These changes were instituted in November 2014, and the team trained clinicians on them through January 2015. Since then, the team has reassessed the situation several times, tracking 291 patients in all. They saw improvement in all three time periods, which was significant in two of them.

Arrival to fluid bolus time dropped significantly, from 55 minutes to 53 minutes – an improvement, even though the baseline time was still within the goal. Fluid bolus-to-insulin time fell significantly as well, from 96 minutes to 74 minutes – well within the new goal.

Overall arrival-to-insulin time thus decreased, from 168 minutes to 146 minutes. However, Dr. Vajravelu said, this is still longer than their goal of less than 120 minutes from door to treatment.

“We are now going back to try and see just where the delay still is,” she said. “It may be getting IV access; it may be labs. We need to tease that out.”

Fortunately, the consistent delays in treatment haven’t resulted in any adverse clinical outcomes.

“I think the biggest benefit we will see will be saving time and money in the emergency department,” Dr. Vajravelu predicted. “We hope to get patients out of there faster, getting them admitted into the hospital and treated in the appropriate department. Speeding up care and reducing waste go together in that sense.”

Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_gal

ORLANDO – A few simple adjustments in standing orders shaved 20 minutes off the time one emergency department took to deliver insulin to pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, according to Mary Ellen Vajravelu, MD.

Door-to-insulin time decreased from a mean of 168 minutes to 146 minutes after the changes went into effect. Most of the time was saved in the period between starting the initial fluid bolus and starting the insulin, she said during an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

A single patient’s experience inspired the quality improvement project.

“A couple of years ago, we saw a patient in the emergency department with diabetic ketoacidosis who had to wait more than 6 hours before insulin was started,” she explained. “Fortunately, there were no adverse clinical outcomes from that,” but the case signaled that the treatment process needed some streamlining.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes recommends immediate fluid administration and insulin within 1-2 hours of starting fluid replacement.

The hospital had been following in-house recommendations for fluids, insulin, and labs for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis that were established in 2006 and 2011. When they examined a baseline cohort of patients treated from January to October 2014, they immediately saw that those order sets were not achieving the recommended times.

“We went back and looked at our cases and saw that overall, it was taking more than 2 hours from the time of arrival for these patients to get their insulin,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

She and her colleagues formed a quality improvement team consisting of physicians, nurses, and a pharmacist. They broke down the wait time into three components: arrival to fluid bolus, fluid bolus start to insulin start, and the overall arrival-to-insulin time. They then set specific time goals for each of those periods: giving fluids within 60 minutes of arrival, starting insulin 45-90 minutes from the bolus, and an overall door-to-insulin time of less than 120 minutes.

The team tried to determine key clinical drivers that were affecting these times. One of the first findings was a delay in diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). This was driven by lack of consistency in scoring patient acuity and problems with venous access.

“To address this, we standardized acuity scoring, got an IV team involved, and used point-of-care labs when possible, and educated our providers,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

The team also found that there were delays in ordering the insulin. These were driven by long wait times for intravenous fluids, by waiting for endocrinology consults, and by providers not being familiar with the DKA order sets.

To address these issues, the team changed the order set to use normal saline for all suspected DKA patients without waiting for lab results. The old orders called for delivering the fluid over a 1-hour period; that was changed to running it over 30 minutes, Dr. Vajravelu said. “That shaved off half an hour right there.”

The team examined reasons that insulin infusion was delayed. Pharmacy orders were a big part of this problem, one of which was the way the insulin was sent up from the pharmacy in a bag. “We changed that to being delivered in a syringe and tube system,” she explained.

They also changed the standing order for when insulin was started, from 60 minutes after fluid to 45 minutes.

These changes were instituted in November 2014, and the team trained clinicians on them through January 2015. Since then, the team has reassessed the situation several times, tracking 291 patients in all. They saw improvement in all three time periods, which was significant in two of them.

Arrival to fluid bolus time dropped significantly, from 55 minutes to 53 minutes – an improvement, even though the baseline time was still within the goal. Fluid bolus-to-insulin time fell significantly as well, from 96 minutes to 74 minutes – well within the new goal.

Overall arrival-to-insulin time thus decreased, from 168 minutes to 146 minutes. However, Dr. Vajravelu said, this is still longer than their goal of less than 120 minutes from door to treatment.

“We are now going back to try and see just where the delay still is,” she said. “It may be getting IV access; it may be labs. We need to tease that out.”

Fortunately, the consistent delays in treatment haven’t resulted in any adverse clinical outcomes.

“I think the biggest benefit we will see will be saving time and money in the emergency department,” Dr. Vajravelu predicted. “We hope to get patients out of there faster, getting them admitted into the hospital and treated in the appropriate department. Speeding up care and reducing waste go together in that sense.”

Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_gal

ORLANDO – A few simple adjustments in standing orders shaved 20 minutes off the time one emergency department took to deliver insulin to pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, according to Mary Ellen Vajravelu, MD.

Door-to-insulin time decreased from a mean of 168 minutes to 146 minutes after the changes went into effect. Most of the time was saved in the period between starting the initial fluid bolus and starting the insulin, she said during an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

A single patient’s experience inspired the quality improvement project.

“A couple of years ago, we saw a patient in the emergency department with diabetic ketoacidosis who had to wait more than 6 hours before insulin was started,” she explained. “Fortunately, there were no adverse clinical outcomes from that,” but the case signaled that the treatment process needed some streamlining.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes recommends immediate fluid administration and insulin within 1-2 hours of starting fluid replacement.

The hospital had been following in-house recommendations for fluids, insulin, and labs for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis that were established in 2006 and 2011. When they examined a baseline cohort of patients treated from January to October 2014, they immediately saw that those order sets were not achieving the recommended times.

“We went back and looked at our cases and saw that overall, it was taking more than 2 hours from the time of arrival for these patients to get their insulin,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

She and her colleagues formed a quality improvement team consisting of physicians, nurses, and a pharmacist. They broke down the wait time into three components: arrival to fluid bolus, fluid bolus start to insulin start, and the overall arrival-to-insulin time. They then set specific time goals for each of those periods: giving fluids within 60 minutes of arrival, starting insulin 45-90 minutes from the bolus, and an overall door-to-insulin time of less than 120 minutes.

The team tried to determine key clinical drivers that were affecting these times. One of the first findings was a delay in diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). This was driven by lack of consistency in scoring patient acuity and problems with venous access.

“To address this, we standardized acuity scoring, got an IV team involved, and used point-of-care labs when possible, and educated our providers,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

The team also found that there were delays in ordering the insulin. These were driven by long wait times for intravenous fluids, by waiting for endocrinology consults, and by providers not being familiar with the DKA order sets.

To address these issues, the team changed the order set to use normal saline for all suspected DKA patients without waiting for lab results. The old orders called for delivering the fluid over a 1-hour period; that was changed to running it over 30 minutes, Dr. Vajravelu said. “That shaved off half an hour right there.”

The team examined reasons that insulin infusion was delayed. Pharmacy orders were a big part of this problem, one of which was the way the insulin was sent up from the pharmacy in a bag. “We changed that to being delivered in a syringe and tube system,” she explained.

They also changed the standing order for when insulin was started, from 60 minutes after fluid to 45 minutes.

These changes were instituted in November 2014, and the team trained clinicians on them through January 2015. Since then, the team has reassessed the situation several times, tracking 291 patients in all. They saw improvement in all three time periods, which was significant in two of them.

Arrival to fluid bolus time dropped significantly, from 55 minutes to 53 minutes – an improvement, even though the baseline time was still within the goal. Fluid bolus-to-insulin time fell significantly as well, from 96 minutes to 74 minutes – well within the new goal.

Overall arrival-to-insulin time thus decreased, from 168 minutes to 146 minutes. However, Dr. Vajravelu said, this is still longer than their goal of less than 120 minutes from door to treatment.

“We are now going back to try and see just where the delay still is,” she said. “It may be getting IV access; it may be labs. We need to tease that out.”

Fortunately, the consistent delays in treatment haven’t resulted in any adverse clinical outcomes.

“I think the biggest benefit we will see will be saving time and money in the emergency department,” Dr. Vajravelu predicted. “We hope to get patients out of there faster, getting them admitted into the hospital and treated in the appropriate department. Speeding up care and reducing waste go together in that sense.”

Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_gal

AT ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall door-to-insulin time decreased from 168 minutes to 146 minutes.

Data source: A 2-year quality improvement project involving 291 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.