User login

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are unique synthetic compounds that bind to the estrogen receptor and initiate either estrogenic agonistic or antagonistic activity, depending on the confirmational change they produce on binding to the receptor. Many SERMs have come to market, others have not. Unlike estrogens, which regardless of dose or route of administration all carry risks as a boxed warning on the label, referred to as class labeling,1 various SERMs exert various effects in some tissues (uterus, vagina) while they have apparent class properties in others (bone, breast).2

The first SERM, for all practical purposes, was tamoxifen (although clomiphene citrate is often considered a SERM). Tamoxifen was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1978 for the treatment of breast cancer and, subsequently, for breast cancer risk reduction. It became the most widely prescribed anticancer drug worldwide.

Subsequently, when data showed that tamoxifen could produce a small number of endometrial cancers and a larger number of endometrial polyps,3,4 there was renewed interest in raloxifene. In preclinical animal studies, raloxifene behaved differently than tamoxifen in the uterus. After clinical trials with raloxifene showed uterine safety,5 the drug was FDA approved for prevention of osteoporosis in 1997, for treatment of osteoporosis in 1999, and for breast cancer risk reduction in 2009. Most clinicians are familiar with these 2 SERMs, which have been in clinical use for more than 4 and 2 decades, respectively.

Ospemifene: A third-generation SERM and its indications

Hormone deficiency from menopause causes vulvovaginal and urogenital changes as well as a multitude of symptoms and signs, including vulvar and vaginal thinning, loss of rugal folds, diminished elasticity, increased pH, and most notably dyspareunia. The nomenclature that previously described vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) has been expanded to include genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM).6 Unfortunately, many health care providers do not ask patients about GSM symptoms, and few women report their symptoms to their clinician.7 Furthermore, although low-dose local estrogens applied vaginally have been the mainstay of therapy for VVA/GSM, only 7% of symptomatic women use any pharmacologic agent,8 mainly because of fear of estrogens due to the class labeling mentioned above.

Ospemifene, a newer SERM, improved superficial cells and reduced parabasal cells as seen on a maturation index compared with placebo, according to results of multiple phase 3 clinical trials9,10; it also lowered vaginal pH and improved most bothersome symptoms (original studies were for dyspareunia). As a result, the FDA approved ospemifene for treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia from VVA of menopause.

Subsequent studies allowed for a broadened indication to include treatment of moderate to severe dryness due to menopause.11 The ospemifene label contains a boxed warning that states, “In the endometrium, [ospemifene] has estrogen agonistic effects.”12 Although ospemifene is not an estrogen (it’s a SERM), the label goes on to state, “There is an increased risk of endometrial cancer in a woman with a uterus who uses unopposed estrogens.” This statement caused The Medical Letter to initially suggest that patients who receive ospemifene also should receive a progestational agent—a suggestion they later retracted.13,14

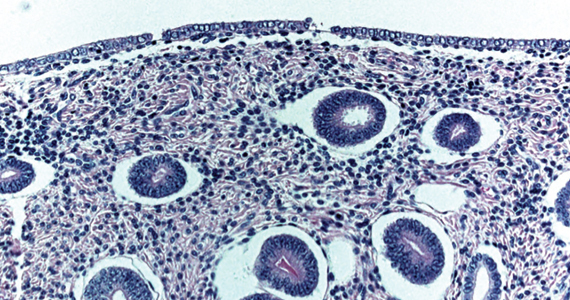

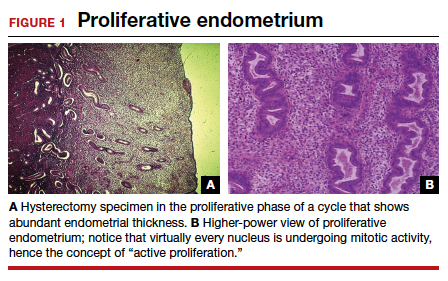

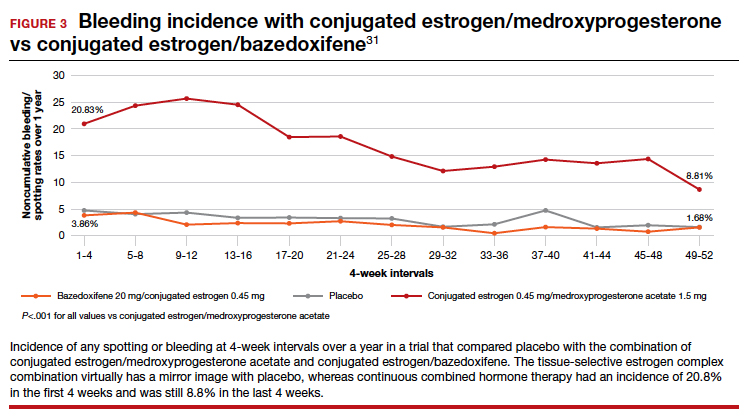

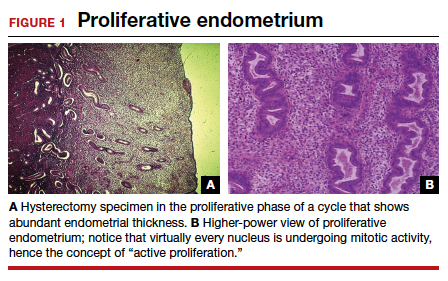

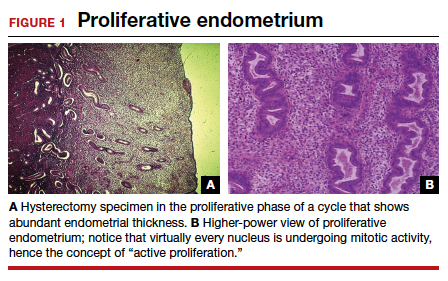

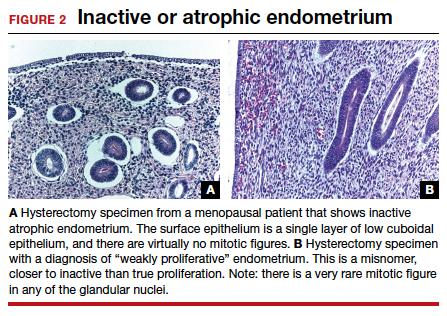

To understand why the ospemifene labeling might be worded in such a way, one must review the data regarding the poorly named entity “weakly proliferative endometrium.” The package labeling combines any proliferative endometrium (“weakly” plus “actively” plus “disordered”) that occurred in the clinical trial. Thus, 86.1 per 1,000 of the ospemifene-treated patients (vs 13.3 per 1,000 of those taking placebo) had any one of the proliferative types. The problem is that “actively proliferative” endometrial glands will have mitotic activity in virtually every nucleus of the gland as well as abundant glandular progression (FIGURE 1), whereas “weakly proliferative” is actually closer to inactive or atrophic endometrium with an occasional mitotic figure in only a few nuclei of each gland (FIGURE 2).

In addition, at 1 year, the incidence of active proliferation with ospemifene was 1%.15 In examining the uterine safety study for raloxifene, both doses of that agent had an active proliferation incidence of 3% at 1 year.5 Furthermore, that study had an estrogen-only arm in which, at end point, the incidence of endometrial proliferation was 39%, and hyperplasia, 23%!5 It therefore is evident that, in the endometrium, ospemifene is much more like the SERM raloxifene than it is like estrogen. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) endorsed ospemifene (level A evidence) as a first-line therapy for dyspareunia, noting absent endometrial stimulation.16

Continue to: Ospemifene effects on breast and bone...

Ospemifene effects on breast and bone

Although ospemifene is approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA/GSM, it has other SERM effects typical of its class. The label currently states that ospemifene “has not been adequately studied in women with breast cancer; therefore, it should not be used in women with known or suspected breast cancer.”12 We know that tamoxifen reduced breast cancer 49% in high-risk women in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT).17 We also know that in the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial, raloxifene reduced breast cancer 77% in osteoporotic women,18 and in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial, it performed virtually identically to tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention.19 Previous studies demonstrated that ospemifene inhibits breast cancer cell growth in in vitro cultures as well as in animal studies20 and inhibits proliferation of human breast tissue epithelial cells,21 with breast effects similar to those seen with tamoxifen and raloxifene.

Thus, although one would not choose ospemifene as a primary treatment or risk-reducing agent for a patient with breast cancer, the direction of its activity in breast tissue is indisputable and is likely the reason that in the European Union (unlike in the United States) it is approved to treat dyspareunia from VVA/GSM in women with a prior history of breast cancer.

Virtually all SERMs have estrogen agonistic activity in bone. Bone is a dynamic organ, constantly being laid down and taken away (resorption). Estrogen and SERMs are potent antiresorptives in bone metabolism. Ospemifene effectively reduced bone loss in ovariectomized rats, with activity comparable to that of estradiol and raloxifene.22 Clinical data from 3 phase 1 or 2 clinical trials found that ospemifene 60 mg/day had a positive effect on biochemical markers for bone turnover in healthy postmenopausal women, with significant improvements relative to placebo and effects comparable to those of raloxifene.23 Actual fracture or bone mineral density (BMD) data in postmenopausal women are lacking, but there is a good correlation between biochemical markers for bone turnover and the occurrence of fracture.24 Once again, women who need treatment for osteoporosis should not be treated primarily with ospemifene, but women who use ospemifene for dyspareunia can expect positive activity on bone metabolism.

Clinical application

Ospemifene is an oral SERM approved for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia as well as dryness from VVA due to menopause. In addition, it appears one can safely surmise that the direction of ospemifene’s activity in bone and breast is virtually indisputable. The magnitude of that activity, however, is unstudied. Therefore, in selecting an agent to treat women with dyspareunia or vaginal dryness from VVA of menopause, determining any potential add-on benefit for that particular patient in either bone and/or breast is clinically appropriate.

The SERM bazedoxifene

A meta-analysis of 4 randomized, placebo-controlled trials showed that another SERM, bazedoxifene, can significantly decrease the incidence of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women at follow-up of 3 and 7 years.25 That meta-analysis also confirmed the long-term favorable safety and tolerability of bazedoxifene, with no increase in adverse events, serious adverse events, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolic events, or breast carcinoma in patients using bazedoxifene. However, bazedoxifene use did result in an increased incidence of hot flushes and leg cramps across 7 years.25 Bazedoxifene is available in a 20-mg dose for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Israel and a number of European Union countries.

Continue to: Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)...

Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)

Some postmenopausal women are extremely intolerant of any progestogen added to estrogen therapy to confer endometrial protection in those with a uterus. According to the results of a clinical trial of postmenopausal women, bazedoxifene is the only SERM shown to decrease endometrial thickness compared with placebo.26 This is the basis for thinking that perhaps a SERM like bazedoxifene, instead of a progestogen, could be used to confer endometrial protection.

A further consideration comes out of the evaluation of data derived from the 2 arms of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).27 In the arm that combined conjugated estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate through 11.3 years, there was a 25% increase in the incidence of invasive breast cancer, which was statistically significant. Contrast that with the arm in hysterectomized women who received only conjugated estrogen (often inaccurately referred to as the “estrogen only” arm of the WHI). In that study arm, the relative risk of invasive breast cancer was reduced 23%, also statistically significant. Thus, the culprit in the breast cancer incidence difference in these 2 arms appears to be the addition of the progestogen medroxyprogesterone acetate.27

Since the progestogen was used only for endometrial protection, could such endometrial protection be provided by a SERM like bazedoxifene? Preclinical trials showed that a combination of bazedoxifene and conjugated estrogen (in various estrogen doses) resulted in uterine wet weight in an ovariectomized rat model that was no different than that with placebo.28

In terms of effects on breast, preclinical models showed that conjugated estrogen use resulted in less mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation than estradiol by itself, and that the combination of conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene resulted in mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation that was similar to that in the ovariectomized animals and considerably less than a combination of estradiol with bazedoxifene.29

Five phase 3 studies known as the SMART (Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy) trials were then conducted. Collectively, these studies examined the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms (VMS), BMD, bone turnover markers, lipid profiles, sleep, quality of life, breast density, and endometrial safety with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene treatment.30 Based on these trials with more than 7,500 women, in 2013 the FDA approved a compound of conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene 20 mg (Duavee in the United States and Duavive outside the United States).

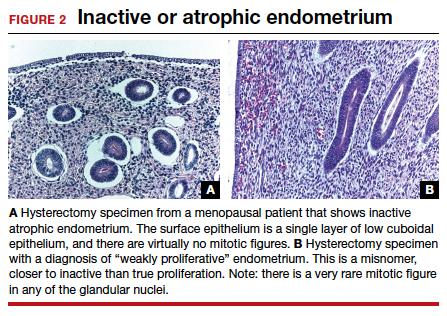

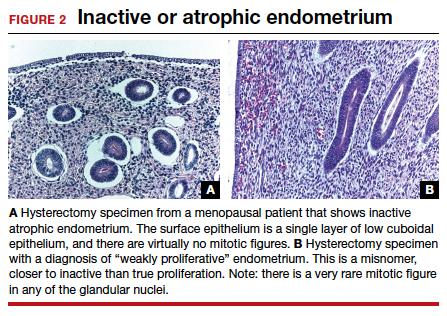

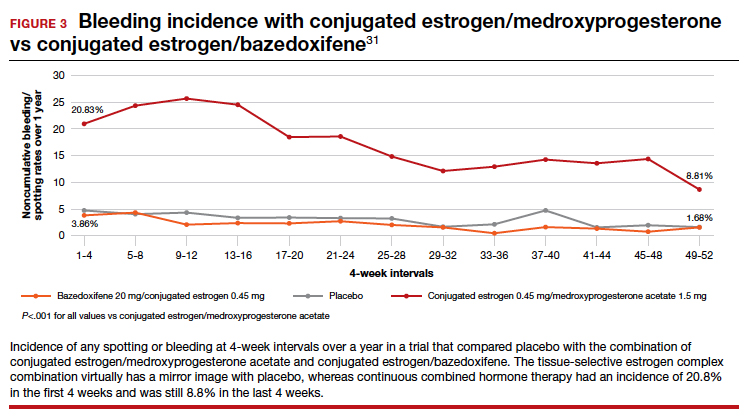

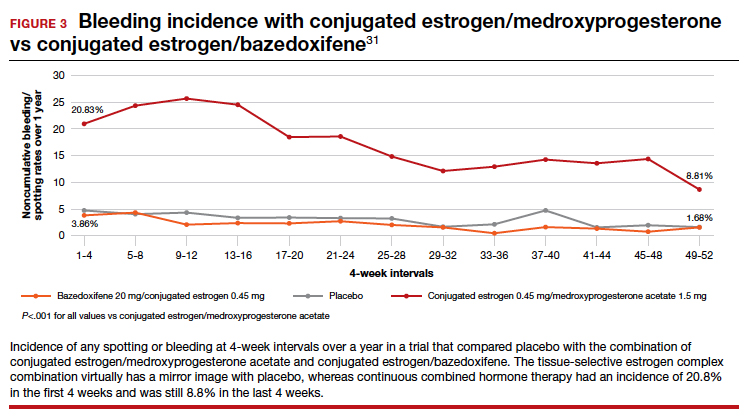

The incidence of endometrial hyperplasia at 12 months was consistently less than 1%, which is the FDA guidance for approval of hormone therapies. The incidence of bleeding or spotting with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene (FIGURE 3) in each 4-week interval over 12 months mirror-imaged that of placebo and ranged from 3.9% in the first 4-week interval to 1.7% in the last 4 weeks, compared with conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg/medroxyprogesterone acetate 1.5 mg, which had a 20.8% incidence of bleeding or spotting in the first 4-week interval and was still at an 8.8% incidence in the last 4 weeks.31 This is extremely relevant in clinical practice. There was no difference from placebo in breast cancer incidence, breast pain or tenderness, abnormal mammograms, or breast density at month 12.32

In terms of frequency of VMS, there was a 74% reduction from baseline at 12 weeks compared with placebo (P<.001), as well as a 37% reduction in the VMS severity score (P<.001).32 Statistically significant improvements occurred in lumbar spine and hip BMD (P<.01) for women who were 1 to 5 years since menopause as well as for those who were more than 5 years since menopause.33

Packaging issue puts TSEC on back order

In May 2020, Pfizer voluntarily recalled its conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene product after identifying a “flaw in the drug’s foil laminate pouch that introduced oxygen and lowered the dissolution rate of active pharmaceutical ingredient bazedoxifene acetate.”34 The manufacturer then wrote a letter to health care professionals in September 2021 stating, “Duavee continues to be out of stock due to an unexpected and complex packaging issue, resulting in manufacturing delays. This has nothing to do with the safety or quality of the product itself but could affect product stability throughout its shelf life… Given regulatory approval timelines for any new packaging, it is unlikely that Duavee will return to stock in 2022.”35

Other TSECs?

The conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene combination is the first FDA-approved TSEC. Other attempts have been made to achieve similar results with combined raloxifene and 17β-estradiol.36 That study was meant to be a 52-week treatment trial with either raloxifene 60 mg alone or in combination with 17β-estradiol 1 mg per day to assess effects on VMS and endometrial safety. The study was stopped early because signs of endometrial stimulation were observed in the raloxifene plus estradiol group. Thus, one cannot combine any estrogen with any SERM and assume similar results.

Clinical application

The combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene is approved for treatment of VMS of menopause as well as prevention of osteoporosis. Although it is not approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA, in younger women who initiate treatment it should prevent the development of moderate to severe symptoms of VVA.

Finally, this drug should be protective of the breast. Conjugated estrogen has clearly shown a reduction in breast cancer incidence and mortality, and bazedoxifene is a SERM. All SERMs have, as a class effect, been shown to be antiestrogens in breast tissue, and abundant preclinical data point in that direction.

This combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene, when it is once again clinically available, may well provide a new paradigm of hormone therapy that is progestogen free and has a benefit/risk ratio that tilts toward its benefits.

Potential for wider therapeutic benefits

Newer SERMs like ospemifene, approved for treatment of VVA/GSM, and bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogen combination, approved for treatment of VMS and prevention of bone loss, have other beneficial properties that can and should result in their more widespread use. ●

- Stuenkel CA. More evidence why the product labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen should be changed? Menopause. 2018;25:4-6.

- Goldstein SR. Not all SERMs are created equal. Menopause. 2006;13:325-327.

- Neven P, De Muylder X, Van Belle Y, et al. Hysteroscopic follow-up during tamoxifen treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;35:235-238.

- Schwartz LB, Snyder J, Horan C, et al. The use of transvaginal ultrasound and saline infusion sonohysterography for the evaluation of asymptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer patients on tamoxifen. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11:48-53.

- Goldstein SR, Scheele WH, Rajagopalan SK, et al. A 12-month comparative study of raloxifene, estrogen, and placebo on the postmenopausal endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:95-103.

- Portman DJ, Gass MLS. Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063-1068.

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:437-447.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S, et al. The Women’s EMPOWER Survey: identifying women’s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. J Sex Med. 2017;14:413-424.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17:480-486.

- Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20:623-630.

- Archer DF, Goldstein SR, Simon JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ospemifene in postmenopausal women with moderateto-severe vaginal dryness: a phase 3, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Menopause. 2019;26:611-621.

- Osphena. Package insert. Shionogi Inc; 2018.

- Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:55-56.

- Addendum: Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia (Med Lett Drugs Ther 2013;55:55). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:84.

- Goldstein SR, Bachmann G, Lin V, et al. Endometrial safety profile of ospemifene 60 mg when used for long-term treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy for up to 1 year. Abstract. Climacteric. 2011;14(suppl 1):S57.

- ACOG practice bulletin no. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371-1388.

- Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, et al. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation. JAMA. 1999;281:2189-2197.

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al; National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727-2741.

- Qu Q, Zheng H, Dahllund J, et al. Selective estrogenic effects of a novel triphenylethylene compound, FC1271a, on bone, cholesterol level, and reproductive tissues in intact and ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2000;141:809-820.

- Eigeliene N, Kangas L, Hellmer C, et al. Effects of ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen-receptor modulator, on human breast tissue ex vivo. Menopause. 2016;23:719-730.

- Kangas L, Unkila M. Tissue selectivity of ospemifene: pharmacologic profile and clinical implications. Steroids. 2013;78:1273-1280.

- Constantine GD, Kagan R, Miller PD. Effects of ospemifene on bone parameters including clinical biomarkers in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:638-644.

- Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:386-393.

- Peng L, Luo Q, Lu H. Efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(49):e8659.

- Ronkin S, Northington R, Baracat E, et al. Endometrial effects of bazedoxifene acetate, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator, in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1397-1404.

- Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:476-486.

- Kharode Y, Bodine PV, Miller CP, et al. The pairing of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, with conjugated estrogens as a new paradigm for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis prevention. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6084-6091.

- Song Y, Santen RJ, Wang JP, et al. Effects of the conjugated equine estrogen/bazedoxifene tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) on mammary gland and breast cancer in mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5706-5715.

- Umland EM, Karel L, Santoro N. Bazedoxifene and conjugated equine estrogen: a combination product for the management of vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis prevention associated with menopause. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:548-561.

- Kagan R, Goldstein SR, Pickar JH, et al. Patient considerations in the management of menopausal symptoms: role of conjugated estrogens with bazedoxifene. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:549–562.

- Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:959-968.

- Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/ conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1045-1052.

- Fierce Pharma. Pfizer continues recalls of menopause drug Duavee on faulty packaging concerns. https:// www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/pfizer-recallsmenopause-drug-duavive-uk-due-to-faulty-packagingworries. June 9, 2020. Accessed February 8, 2022.

- Pfizer. Letter to health care provider. Subject: Duavee (conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene) extended drug shortage. September 10, 2021.

- Stovall DW, Utian WH, Gass MLS, et al. The effects of combined raloxifene and oral estrogen on vasomotor symptoms and endometrial safety. Menopause. 2007; 14(3 pt 1):510-517.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are unique synthetic compounds that bind to the estrogen receptor and initiate either estrogenic agonistic or antagonistic activity, depending on the confirmational change they produce on binding to the receptor. Many SERMs have come to market, others have not. Unlike estrogens, which regardless of dose or route of administration all carry risks as a boxed warning on the label, referred to as class labeling,1 various SERMs exert various effects in some tissues (uterus, vagina) while they have apparent class properties in others (bone, breast).2

The first SERM, for all practical purposes, was tamoxifen (although clomiphene citrate is often considered a SERM). Tamoxifen was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1978 for the treatment of breast cancer and, subsequently, for breast cancer risk reduction. It became the most widely prescribed anticancer drug worldwide.

Subsequently, when data showed that tamoxifen could produce a small number of endometrial cancers and a larger number of endometrial polyps,3,4 there was renewed interest in raloxifene. In preclinical animal studies, raloxifene behaved differently than tamoxifen in the uterus. After clinical trials with raloxifene showed uterine safety,5 the drug was FDA approved for prevention of osteoporosis in 1997, for treatment of osteoporosis in 1999, and for breast cancer risk reduction in 2009. Most clinicians are familiar with these 2 SERMs, which have been in clinical use for more than 4 and 2 decades, respectively.

Ospemifene: A third-generation SERM and its indications

Hormone deficiency from menopause causes vulvovaginal and urogenital changes as well as a multitude of symptoms and signs, including vulvar and vaginal thinning, loss of rugal folds, diminished elasticity, increased pH, and most notably dyspareunia. The nomenclature that previously described vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) has been expanded to include genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM).6 Unfortunately, many health care providers do not ask patients about GSM symptoms, and few women report their symptoms to their clinician.7 Furthermore, although low-dose local estrogens applied vaginally have been the mainstay of therapy for VVA/GSM, only 7% of symptomatic women use any pharmacologic agent,8 mainly because of fear of estrogens due to the class labeling mentioned above.

Ospemifene, a newer SERM, improved superficial cells and reduced parabasal cells as seen on a maturation index compared with placebo, according to results of multiple phase 3 clinical trials9,10; it also lowered vaginal pH and improved most bothersome symptoms (original studies were for dyspareunia). As a result, the FDA approved ospemifene for treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia from VVA of menopause.

Subsequent studies allowed for a broadened indication to include treatment of moderate to severe dryness due to menopause.11 The ospemifene label contains a boxed warning that states, “In the endometrium, [ospemifene] has estrogen agonistic effects.”12 Although ospemifene is not an estrogen (it’s a SERM), the label goes on to state, “There is an increased risk of endometrial cancer in a woman with a uterus who uses unopposed estrogens.” This statement caused The Medical Letter to initially suggest that patients who receive ospemifene also should receive a progestational agent—a suggestion they later retracted.13,14

To understand why the ospemifene labeling might be worded in such a way, one must review the data regarding the poorly named entity “weakly proliferative endometrium.” The package labeling combines any proliferative endometrium (“weakly” plus “actively” plus “disordered”) that occurred in the clinical trial. Thus, 86.1 per 1,000 of the ospemifene-treated patients (vs 13.3 per 1,000 of those taking placebo) had any one of the proliferative types. The problem is that “actively proliferative” endometrial glands will have mitotic activity in virtually every nucleus of the gland as well as abundant glandular progression (FIGURE 1), whereas “weakly proliferative” is actually closer to inactive or atrophic endometrium with an occasional mitotic figure in only a few nuclei of each gland (FIGURE 2).

In addition, at 1 year, the incidence of active proliferation with ospemifene was 1%.15 In examining the uterine safety study for raloxifene, both doses of that agent had an active proliferation incidence of 3% at 1 year.5 Furthermore, that study had an estrogen-only arm in which, at end point, the incidence of endometrial proliferation was 39%, and hyperplasia, 23%!5 It therefore is evident that, in the endometrium, ospemifene is much more like the SERM raloxifene than it is like estrogen. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) endorsed ospemifene (level A evidence) as a first-line therapy for dyspareunia, noting absent endometrial stimulation.16

Continue to: Ospemifene effects on breast and bone...

Ospemifene effects on breast and bone

Although ospemifene is approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA/GSM, it has other SERM effects typical of its class. The label currently states that ospemifene “has not been adequately studied in women with breast cancer; therefore, it should not be used in women with known or suspected breast cancer.”12 We know that tamoxifen reduced breast cancer 49% in high-risk women in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT).17 We also know that in the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial, raloxifene reduced breast cancer 77% in osteoporotic women,18 and in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial, it performed virtually identically to tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention.19 Previous studies demonstrated that ospemifene inhibits breast cancer cell growth in in vitro cultures as well as in animal studies20 and inhibits proliferation of human breast tissue epithelial cells,21 with breast effects similar to those seen with tamoxifen and raloxifene.

Thus, although one would not choose ospemifene as a primary treatment or risk-reducing agent for a patient with breast cancer, the direction of its activity in breast tissue is indisputable and is likely the reason that in the European Union (unlike in the United States) it is approved to treat dyspareunia from VVA/GSM in women with a prior history of breast cancer.

Virtually all SERMs have estrogen agonistic activity in bone. Bone is a dynamic organ, constantly being laid down and taken away (resorption). Estrogen and SERMs are potent antiresorptives in bone metabolism. Ospemifene effectively reduced bone loss in ovariectomized rats, with activity comparable to that of estradiol and raloxifene.22 Clinical data from 3 phase 1 or 2 clinical trials found that ospemifene 60 mg/day had a positive effect on biochemical markers for bone turnover in healthy postmenopausal women, with significant improvements relative to placebo and effects comparable to those of raloxifene.23 Actual fracture or bone mineral density (BMD) data in postmenopausal women are lacking, but there is a good correlation between biochemical markers for bone turnover and the occurrence of fracture.24 Once again, women who need treatment for osteoporosis should not be treated primarily with ospemifene, but women who use ospemifene for dyspareunia can expect positive activity on bone metabolism.

Clinical application

Ospemifene is an oral SERM approved for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia as well as dryness from VVA due to menopause. In addition, it appears one can safely surmise that the direction of ospemifene’s activity in bone and breast is virtually indisputable. The magnitude of that activity, however, is unstudied. Therefore, in selecting an agent to treat women with dyspareunia or vaginal dryness from VVA of menopause, determining any potential add-on benefit for that particular patient in either bone and/or breast is clinically appropriate.

The SERM bazedoxifene

A meta-analysis of 4 randomized, placebo-controlled trials showed that another SERM, bazedoxifene, can significantly decrease the incidence of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women at follow-up of 3 and 7 years.25 That meta-analysis also confirmed the long-term favorable safety and tolerability of bazedoxifene, with no increase in adverse events, serious adverse events, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolic events, or breast carcinoma in patients using bazedoxifene. However, bazedoxifene use did result in an increased incidence of hot flushes and leg cramps across 7 years.25 Bazedoxifene is available in a 20-mg dose for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Israel and a number of European Union countries.

Continue to: Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)...

Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)

Some postmenopausal women are extremely intolerant of any progestogen added to estrogen therapy to confer endometrial protection in those with a uterus. According to the results of a clinical trial of postmenopausal women, bazedoxifene is the only SERM shown to decrease endometrial thickness compared with placebo.26 This is the basis for thinking that perhaps a SERM like bazedoxifene, instead of a progestogen, could be used to confer endometrial protection.

A further consideration comes out of the evaluation of data derived from the 2 arms of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).27 In the arm that combined conjugated estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate through 11.3 years, there was a 25% increase in the incidence of invasive breast cancer, which was statistically significant. Contrast that with the arm in hysterectomized women who received only conjugated estrogen (often inaccurately referred to as the “estrogen only” arm of the WHI). In that study arm, the relative risk of invasive breast cancer was reduced 23%, also statistically significant. Thus, the culprit in the breast cancer incidence difference in these 2 arms appears to be the addition of the progestogen medroxyprogesterone acetate.27

Since the progestogen was used only for endometrial protection, could such endometrial protection be provided by a SERM like bazedoxifene? Preclinical trials showed that a combination of bazedoxifene and conjugated estrogen (in various estrogen doses) resulted in uterine wet weight in an ovariectomized rat model that was no different than that with placebo.28

In terms of effects on breast, preclinical models showed that conjugated estrogen use resulted in less mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation than estradiol by itself, and that the combination of conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene resulted in mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation that was similar to that in the ovariectomized animals and considerably less than a combination of estradiol with bazedoxifene.29

Five phase 3 studies known as the SMART (Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy) trials were then conducted. Collectively, these studies examined the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms (VMS), BMD, bone turnover markers, lipid profiles, sleep, quality of life, breast density, and endometrial safety with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene treatment.30 Based on these trials with more than 7,500 women, in 2013 the FDA approved a compound of conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene 20 mg (Duavee in the United States and Duavive outside the United States).

The incidence of endometrial hyperplasia at 12 months was consistently less than 1%, which is the FDA guidance for approval of hormone therapies. The incidence of bleeding or spotting with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene (FIGURE 3) in each 4-week interval over 12 months mirror-imaged that of placebo and ranged from 3.9% in the first 4-week interval to 1.7% in the last 4 weeks, compared with conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg/medroxyprogesterone acetate 1.5 mg, which had a 20.8% incidence of bleeding or spotting in the first 4-week interval and was still at an 8.8% incidence in the last 4 weeks.31 This is extremely relevant in clinical practice. There was no difference from placebo in breast cancer incidence, breast pain or tenderness, abnormal mammograms, or breast density at month 12.32

In terms of frequency of VMS, there was a 74% reduction from baseline at 12 weeks compared with placebo (P<.001), as well as a 37% reduction in the VMS severity score (P<.001).32 Statistically significant improvements occurred in lumbar spine and hip BMD (P<.01) for women who were 1 to 5 years since menopause as well as for those who were more than 5 years since menopause.33

Packaging issue puts TSEC on back order

In May 2020, Pfizer voluntarily recalled its conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene product after identifying a “flaw in the drug’s foil laminate pouch that introduced oxygen and lowered the dissolution rate of active pharmaceutical ingredient bazedoxifene acetate.”34 The manufacturer then wrote a letter to health care professionals in September 2021 stating, “Duavee continues to be out of stock due to an unexpected and complex packaging issue, resulting in manufacturing delays. This has nothing to do with the safety or quality of the product itself but could affect product stability throughout its shelf life… Given regulatory approval timelines for any new packaging, it is unlikely that Duavee will return to stock in 2022.”35

Other TSECs?

The conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene combination is the first FDA-approved TSEC. Other attempts have been made to achieve similar results with combined raloxifene and 17β-estradiol.36 That study was meant to be a 52-week treatment trial with either raloxifene 60 mg alone or in combination with 17β-estradiol 1 mg per day to assess effects on VMS and endometrial safety. The study was stopped early because signs of endometrial stimulation were observed in the raloxifene plus estradiol group. Thus, one cannot combine any estrogen with any SERM and assume similar results.

Clinical application

The combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene is approved for treatment of VMS of menopause as well as prevention of osteoporosis. Although it is not approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA, in younger women who initiate treatment it should prevent the development of moderate to severe symptoms of VVA.

Finally, this drug should be protective of the breast. Conjugated estrogen has clearly shown a reduction in breast cancer incidence and mortality, and bazedoxifene is a SERM. All SERMs have, as a class effect, been shown to be antiestrogens in breast tissue, and abundant preclinical data point in that direction.

This combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene, when it is once again clinically available, may well provide a new paradigm of hormone therapy that is progestogen free and has a benefit/risk ratio that tilts toward its benefits.

Potential for wider therapeutic benefits

Newer SERMs like ospemifene, approved for treatment of VVA/GSM, and bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogen combination, approved for treatment of VMS and prevention of bone loss, have other beneficial properties that can and should result in their more widespread use. ●

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are unique synthetic compounds that bind to the estrogen receptor and initiate either estrogenic agonistic or antagonistic activity, depending on the confirmational change they produce on binding to the receptor. Many SERMs have come to market, others have not. Unlike estrogens, which regardless of dose or route of administration all carry risks as a boxed warning on the label, referred to as class labeling,1 various SERMs exert various effects in some tissues (uterus, vagina) while they have apparent class properties in others (bone, breast).2

The first SERM, for all practical purposes, was tamoxifen (although clomiphene citrate is often considered a SERM). Tamoxifen was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1978 for the treatment of breast cancer and, subsequently, for breast cancer risk reduction. It became the most widely prescribed anticancer drug worldwide.

Subsequently, when data showed that tamoxifen could produce a small number of endometrial cancers and a larger number of endometrial polyps,3,4 there was renewed interest in raloxifene. In preclinical animal studies, raloxifene behaved differently than tamoxifen in the uterus. After clinical trials with raloxifene showed uterine safety,5 the drug was FDA approved for prevention of osteoporosis in 1997, for treatment of osteoporosis in 1999, and for breast cancer risk reduction in 2009. Most clinicians are familiar with these 2 SERMs, which have been in clinical use for more than 4 and 2 decades, respectively.

Ospemifene: A third-generation SERM and its indications

Hormone deficiency from menopause causes vulvovaginal and urogenital changes as well as a multitude of symptoms and signs, including vulvar and vaginal thinning, loss of rugal folds, diminished elasticity, increased pH, and most notably dyspareunia. The nomenclature that previously described vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) has been expanded to include genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM).6 Unfortunately, many health care providers do not ask patients about GSM symptoms, and few women report their symptoms to their clinician.7 Furthermore, although low-dose local estrogens applied vaginally have been the mainstay of therapy for VVA/GSM, only 7% of symptomatic women use any pharmacologic agent,8 mainly because of fear of estrogens due to the class labeling mentioned above.

Ospemifene, a newer SERM, improved superficial cells and reduced parabasal cells as seen on a maturation index compared with placebo, according to results of multiple phase 3 clinical trials9,10; it also lowered vaginal pH and improved most bothersome symptoms (original studies were for dyspareunia). As a result, the FDA approved ospemifene for treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia from VVA of menopause.

Subsequent studies allowed for a broadened indication to include treatment of moderate to severe dryness due to menopause.11 The ospemifene label contains a boxed warning that states, “In the endometrium, [ospemifene] has estrogen agonistic effects.”12 Although ospemifene is not an estrogen (it’s a SERM), the label goes on to state, “There is an increased risk of endometrial cancer in a woman with a uterus who uses unopposed estrogens.” This statement caused The Medical Letter to initially suggest that patients who receive ospemifene also should receive a progestational agent—a suggestion they later retracted.13,14

To understand why the ospemifene labeling might be worded in such a way, one must review the data regarding the poorly named entity “weakly proliferative endometrium.” The package labeling combines any proliferative endometrium (“weakly” plus “actively” plus “disordered”) that occurred in the clinical trial. Thus, 86.1 per 1,000 of the ospemifene-treated patients (vs 13.3 per 1,000 of those taking placebo) had any one of the proliferative types. The problem is that “actively proliferative” endometrial glands will have mitotic activity in virtually every nucleus of the gland as well as abundant glandular progression (FIGURE 1), whereas “weakly proliferative” is actually closer to inactive or atrophic endometrium with an occasional mitotic figure in only a few nuclei of each gland (FIGURE 2).

In addition, at 1 year, the incidence of active proliferation with ospemifene was 1%.15 In examining the uterine safety study for raloxifene, both doses of that agent had an active proliferation incidence of 3% at 1 year.5 Furthermore, that study had an estrogen-only arm in which, at end point, the incidence of endometrial proliferation was 39%, and hyperplasia, 23%!5 It therefore is evident that, in the endometrium, ospemifene is much more like the SERM raloxifene than it is like estrogen. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) endorsed ospemifene (level A evidence) as a first-line therapy for dyspareunia, noting absent endometrial stimulation.16

Continue to: Ospemifene effects on breast and bone...

Ospemifene effects on breast and bone

Although ospemifene is approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA/GSM, it has other SERM effects typical of its class. The label currently states that ospemifene “has not been adequately studied in women with breast cancer; therefore, it should not be used in women with known or suspected breast cancer.”12 We know that tamoxifen reduced breast cancer 49% in high-risk women in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT).17 We also know that in the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial, raloxifene reduced breast cancer 77% in osteoporotic women,18 and in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial, it performed virtually identically to tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention.19 Previous studies demonstrated that ospemifene inhibits breast cancer cell growth in in vitro cultures as well as in animal studies20 and inhibits proliferation of human breast tissue epithelial cells,21 with breast effects similar to those seen with tamoxifen and raloxifene.

Thus, although one would not choose ospemifene as a primary treatment or risk-reducing agent for a patient with breast cancer, the direction of its activity in breast tissue is indisputable and is likely the reason that in the European Union (unlike in the United States) it is approved to treat dyspareunia from VVA/GSM in women with a prior history of breast cancer.

Virtually all SERMs have estrogen agonistic activity in bone. Bone is a dynamic organ, constantly being laid down and taken away (resorption). Estrogen and SERMs are potent antiresorptives in bone metabolism. Ospemifene effectively reduced bone loss in ovariectomized rats, with activity comparable to that of estradiol and raloxifene.22 Clinical data from 3 phase 1 or 2 clinical trials found that ospemifene 60 mg/day had a positive effect on biochemical markers for bone turnover in healthy postmenopausal women, with significant improvements relative to placebo and effects comparable to those of raloxifene.23 Actual fracture or bone mineral density (BMD) data in postmenopausal women are lacking, but there is a good correlation between biochemical markers for bone turnover and the occurrence of fracture.24 Once again, women who need treatment for osteoporosis should not be treated primarily with ospemifene, but women who use ospemifene for dyspareunia can expect positive activity on bone metabolism.

Clinical application

Ospemifene is an oral SERM approved for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia as well as dryness from VVA due to menopause. In addition, it appears one can safely surmise that the direction of ospemifene’s activity in bone and breast is virtually indisputable. The magnitude of that activity, however, is unstudied. Therefore, in selecting an agent to treat women with dyspareunia or vaginal dryness from VVA of menopause, determining any potential add-on benefit for that particular patient in either bone and/or breast is clinically appropriate.

The SERM bazedoxifene

A meta-analysis of 4 randomized, placebo-controlled trials showed that another SERM, bazedoxifene, can significantly decrease the incidence of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women at follow-up of 3 and 7 years.25 That meta-analysis also confirmed the long-term favorable safety and tolerability of bazedoxifene, with no increase in adverse events, serious adverse events, myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thromboembolic events, or breast carcinoma in patients using bazedoxifene. However, bazedoxifene use did result in an increased incidence of hot flushes and leg cramps across 7 years.25 Bazedoxifene is available in a 20-mg dose for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Israel and a number of European Union countries.

Continue to: Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)...

Enter the concept of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC)

Some postmenopausal women are extremely intolerant of any progestogen added to estrogen therapy to confer endometrial protection in those with a uterus. According to the results of a clinical trial of postmenopausal women, bazedoxifene is the only SERM shown to decrease endometrial thickness compared with placebo.26 This is the basis for thinking that perhaps a SERM like bazedoxifene, instead of a progestogen, could be used to confer endometrial protection.

A further consideration comes out of the evaluation of data derived from the 2 arms of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).27 In the arm that combined conjugated estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate through 11.3 years, there was a 25% increase in the incidence of invasive breast cancer, which was statistically significant. Contrast that with the arm in hysterectomized women who received only conjugated estrogen (often inaccurately referred to as the “estrogen only” arm of the WHI). In that study arm, the relative risk of invasive breast cancer was reduced 23%, also statistically significant. Thus, the culprit in the breast cancer incidence difference in these 2 arms appears to be the addition of the progestogen medroxyprogesterone acetate.27

Since the progestogen was used only for endometrial protection, could such endometrial protection be provided by a SERM like bazedoxifene? Preclinical trials showed that a combination of bazedoxifene and conjugated estrogen (in various estrogen doses) resulted in uterine wet weight in an ovariectomized rat model that was no different than that with placebo.28

In terms of effects on breast, preclinical models showed that conjugated estrogen use resulted in less mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation than estradiol by itself, and that the combination of conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene resulted in mammary duct elongation and end bud proliferation that was similar to that in the ovariectomized animals and considerably less than a combination of estradiol with bazedoxifene.29

Five phase 3 studies known as the SMART (Selective estrogens, Menopause, And Response to Therapy) trials were then conducted. Collectively, these studies examined the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms (VMS), BMD, bone turnover markers, lipid profiles, sleep, quality of life, breast density, and endometrial safety with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene treatment.30 Based on these trials with more than 7,500 women, in 2013 the FDA approved a compound of conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene 20 mg (Duavee in the United States and Duavive outside the United States).

The incidence of endometrial hyperplasia at 12 months was consistently less than 1%, which is the FDA guidance for approval of hormone therapies. The incidence of bleeding or spotting with conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene (FIGURE 3) in each 4-week interval over 12 months mirror-imaged that of placebo and ranged from 3.9% in the first 4-week interval to 1.7% in the last 4 weeks, compared with conjugated estrogen 0.45 mg/medroxyprogesterone acetate 1.5 mg, which had a 20.8% incidence of bleeding or spotting in the first 4-week interval and was still at an 8.8% incidence in the last 4 weeks.31 This is extremely relevant in clinical practice. There was no difference from placebo in breast cancer incidence, breast pain or tenderness, abnormal mammograms, or breast density at month 12.32

In terms of frequency of VMS, there was a 74% reduction from baseline at 12 weeks compared with placebo (P<.001), as well as a 37% reduction in the VMS severity score (P<.001).32 Statistically significant improvements occurred in lumbar spine and hip BMD (P<.01) for women who were 1 to 5 years since menopause as well as for those who were more than 5 years since menopause.33

Packaging issue puts TSEC on back order

In May 2020, Pfizer voluntarily recalled its conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene product after identifying a “flaw in the drug’s foil laminate pouch that introduced oxygen and lowered the dissolution rate of active pharmaceutical ingredient bazedoxifene acetate.”34 The manufacturer then wrote a letter to health care professionals in September 2021 stating, “Duavee continues to be out of stock due to an unexpected and complex packaging issue, resulting in manufacturing delays. This has nothing to do with the safety or quality of the product itself but could affect product stability throughout its shelf life… Given regulatory approval timelines for any new packaging, it is unlikely that Duavee will return to stock in 2022.”35

Other TSECs?

The conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene combination is the first FDA-approved TSEC. Other attempts have been made to achieve similar results with combined raloxifene and 17β-estradiol.36 That study was meant to be a 52-week treatment trial with either raloxifene 60 mg alone or in combination with 17β-estradiol 1 mg per day to assess effects on VMS and endometrial safety. The study was stopped early because signs of endometrial stimulation were observed in the raloxifene plus estradiol group. Thus, one cannot combine any estrogen with any SERM and assume similar results.

Clinical application

The combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene is approved for treatment of VMS of menopause as well as prevention of osteoporosis. Although it is not approved for treatment of moderate to severe VVA, in younger women who initiate treatment it should prevent the development of moderate to severe symptoms of VVA.

Finally, this drug should be protective of the breast. Conjugated estrogen has clearly shown a reduction in breast cancer incidence and mortality, and bazedoxifene is a SERM. All SERMs have, as a class effect, been shown to be antiestrogens in breast tissue, and abundant preclinical data point in that direction.

This combination of conjugated estrogen/bazedoxifene, when it is once again clinically available, may well provide a new paradigm of hormone therapy that is progestogen free and has a benefit/risk ratio that tilts toward its benefits.

Potential for wider therapeutic benefits

Newer SERMs like ospemifene, approved for treatment of VVA/GSM, and bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogen combination, approved for treatment of VMS and prevention of bone loss, have other beneficial properties that can and should result in their more widespread use. ●

- Stuenkel CA. More evidence why the product labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen should be changed? Menopause. 2018;25:4-6.

- Goldstein SR. Not all SERMs are created equal. Menopause. 2006;13:325-327.

- Neven P, De Muylder X, Van Belle Y, et al. Hysteroscopic follow-up during tamoxifen treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;35:235-238.

- Schwartz LB, Snyder J, Horan C, et al. The use of transvaginal ultrasound and saline infusion sonohysterography for the evaluation of asymptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer patients on tamoxifen. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11:48-53.

- Goldstein SR, Scheele WH, Rajagopalan SK, et al. A 12-month comparative study of raloxifene, estrogen, and placebo on the postmenopausal endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:95-103.

- Portman DJ, Gass MLS. Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063-1068.

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:437-447.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S, et al. The Women’s EMPOWER Survey: identifying women’s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. J Sex Med. 2017;14:413-424.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17:480-486.

- Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20:623-630.

- Archer DF, Goldstein SR, Simon JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ospemifene in postmenopausal women with moderateto-severe vaginal dryness: a phase 3, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Menopause. 2019;26:611-621.

- Osphena. Package insert. Shionogi Inc; 2018.

- Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:55-56.

- Addendum: Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia (Med Lett Drugs Ther 2013;55:55). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:84.

- Goldstein SR, Bachmann G, Lin V, et al. Endometrial safety profile of ospemifene 60 mg when used for long-term treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy for up to 1 year. Abstract. Climacteric. 2011;14(suppl 1):S57.

- ACOG practice bulletin no. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371-1388.

- Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, et al. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation. JAMA. 1999;281:2189-2197.

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al; National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727-2741.

- Qu Q, Zheng H, Dahllund J, et al. Selective estrogenic effects of a novel triphenylethylene compound, FC1271a, on bone, cholesterol level, and reproductive tissues in intact and ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2000;141:809-820.

- Eigeliene N, Kangas L, Hellmer C, et al. Effects of ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen-receptor modulator, on human breast tissue ex vivo. Menopause. 2016;23:719-730.

- Kangas L, Unkila M. Tissue selectivity of ospemifene: pharmacologic profile and clinical implications. Steroids. 2013;78:1273-1280.

- Constantine GD, Kagan R, Miller PD. Effects of ospemifene on bone parameters including clinical biomarkers in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:638-644.

- Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:386-393.

- Peng L, Luo Q, Lu H. Efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(49):e8659.

- Ronkin S, Northington R, Baracat E, et al. Endometrial effects of bazedoxifene acetate, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator, in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1397-1404.

- Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:476-486.

- Kharode Y, Bodine PV, Miller CP, et al. The pairing of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, with conjugated estrogens as a new paradigm for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis prevention. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6084-6091.

- Song Y, Santen RJ, Wang JP, et al. Effects of the conjugated equine estrogen/bazedoxifene tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) on mammary gland and breast cancer in mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5706-5715.

- Umland EM, Karel L, Santoro N. Bazedoxifene and conjugated equine estrogen: a combination product for the management of vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis prevention associated with menopause. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:548-561.

- Kagan R, Goldstein SR, Pickar JH, et al. Patient considerations in the management of menopausal symptoms: role of conjugated estrogens with bazedoxifene. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:549–562.

- Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:959-968.

- Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/ conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1045-1052.

- Fierce Pharma. Pfizer continues recalls of menopause drug Duavee on faulty packaging concerns. https:// www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/pfizer-recallsmenopause-drug-duavive-uk-due-to-faulty-packagingworries. June 9, 2020. Accessed February 8, 2022.

- Pfizer. Letter to health care provider. Subject: Duavee (conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene) extended drug shortage. September 10, 2021.

- Stovall DW, Utian WH, Gass MLS, et al. The effects of combined raloxifene and oral estrogen on vasomotor symptoms and endometrial safety. Menopause. 2007; 14(3 pt 1):510-517.

- Stuenkel CA. More evidence why the product labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen should be changed? Menopause. 2018;25:4-6.

- Goldstein SR. Not all SERMs are created equal. Menopause. 2006;13:325-327.

- Neven P, De Muylder X, Van Belle Y, et al. Hysteroscopic follow-up during tamoxifen treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;35:235-238.

- Schwartz LB, Snyder J, Horan C, et al. The use of transvaginal ultrasound and saline infusion sonohysterography for the evaluation of asymptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer patients on tamoxifen. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11:48-53.

- Goldstein SR, Scheele WH, Rajagopalan SK, et al. A 12-month comparative study of raloxifene, estrogen, and placebo on the postmenopausal endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:95-103.

- Portman DJ, Gass MLS. Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063-1068.

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:437-447.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman M, Graham S, et al. The Women’s EMPOWER Survey: identifying women’s perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. J Sex Med. 2017;14:413-424.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17:480-486.

- Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20:623-630.

- Archer DF, Goldstein SR, Simon JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ospemifene in postmenopausal women with moderateto-severe vaginal dryness: a phase 3, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Menopause. 2019;26:611-621.

- Osphena. Package insert. Shionogi Inc; 2018.

- Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:55-56.

- Addendum: Ospemifene (Osphena) for dyspareunia (Med Lett Drugs Ther 2013;55:55). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55:84.

- Goldstein SR, Bachmann G, Lin V, et al. Endometrial safety profile of ospemifene 60 mg when used for long-term treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy for up to 1 year. Abstract. Climacteric. 2011;14(suppl 1):S57.

- ACOG practice bulletin no. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371-1388.

- Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, et al. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation. JAMA. 1999;281:2189-2197.

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al; National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727-2741.

- Qu Q, Zheng H, Dahllund J, et al. Selective estrogenic effects of a novel triphenylethylene compound, FC1271a, on bone, cholesterol level, and reproductive tissues in intact and ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2000;141:809-820.

- Eigeliene N, Kangas L, Hellmer C, et al. Effects of ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen-receptor modulator, on human breast tissue ex vivo. Menopause. 2016;23:719-730.

- Kangas L, Unkila M. Tissue selectivity of ospemifene: pharmacologic profile and clinical implications. Steroids. 2013;78:1273-1280.

- Constantine GD, Kagan R, Miller PD. Effects of ospemifene on bone parameters including clinical biomarkers in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2016;23:638-644.

- Gerdhem P, Ivaska KK, Alatalo SL, et al. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism and prediction of fracture in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:386-393.

- Peng L, Luo Q, Lu H. Efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(49):e8659.

- Ronkin S, Northington R, Baracat E, et al. Endometrial effects of bazedoxifene acetate, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator, in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1397-1404.

- Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:476-486.

- Kharode Y, Bodine PV, Miller CP, et al. The pairing of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, with conjugated estrogens as a new paradigm for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis prevention. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6084-6091.

- Song Y, Santen RJ, Wang JP, et al. Effects of the conjugated equine estrogen/bazedoxifene tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) on mammary gland and breast cancer in mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5706-5715.

- Umland EM, Karel L, Santoro N. Bazedoxifene and conjugated equine estrogen: a combination product for the management of vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis prevention associated with menopause. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:548-561.

- Kagan R, Goldstein SR, Pickar JH, et al. Patient considerations in the management of menopausal symptoms: role of conjugated estrogens with bazedoxifene. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:549–562.

- Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:959-968.

- Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex of bazedoxifene/ conjugated estrogens for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1045-1052.

- Fierce Pharma. Pfizer continues recalls of menopause drug Duavee on faulty packaging concerns. https:// www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/pfizer-recallsmenopause-drug-duavive-uk-due-to-faulty-packagingworries. June 9, 2020. Accessed February 8, 2022.

- Pfizer. Letter to health care provider. Subject: Duavee (conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene) extended drug shortage. September 10, 2021.

- Stovall DW, Utian WH, Gass MLS, et al. The effects of combined raloxifene and oral estrogen on vasomotor symptoms and endometrial safety. Menopause. 2007; 14(3 pt 1):510-517.