User login

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

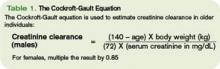

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.

Use of increased numbers of medications and age-related decline in renal function make older patients more susceptible to adverse medication effects. Drug pharmacokinetics change, and it’s important to remember that drug metabolism is affected by a number of processes.

Renal elimination of drugs is based on nephron and renal tubule capacity, which decrease with age.1 Older individuals will not metabolize and excrete drugs as efficiently as younger, healthier individuals.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are more than 36 million adults in the United States older than 65, and overall U.S. healthcare costs related to them are projected to increase 25% by 2030.2

Preventing health problems, preserving patient function, and preventing patient injury that can lead to or prolong patient hospitalizations will help contain these costs.

Quartarolo, et al., recently reported that although physicians noted the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in elderly hospitalized patients, they didn’t modify their prescribing.3 They also noted that drug dose changes in these hospitalized patients are important to prevent dosing errors and adverse reactions.

There are four major age-related pharmacokinetic parameters:

- Usually decreased gastrointestinal absorption changes ;

- Increases or decreases of a drug’s volume of distribution leading to increased blood drug levels and/or plasma-protein-binding changes;

- Usually decreased clearance with increased drug half-life effect (hepatic metabolism changes); and/or

- Decreased clearance (and increased half-life) of renally eliminated drugs.4,5

Renal Effects

Renal excretion of drugs correlates with creatinine clearance. Because lean body mass decreases as people age, the serum creatinine level is a poor gauge of creatinine clearance in older individuals. Creatinine clearance decreases by 50% between age 25 and 85.6 The Cockroft-Gault equation is used to estimate creatinine clearance in older individuals to assist in renal dosing of drugs (See Table 1, above).

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative defines chronic kidney disease (CKD) as:

- Kidney damage for three or more months, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased GFR, marked by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney damage; or

- GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less for three or more months, with or without kidney damage.6

In these patients, adjustment of the drug dose or dosing interval is imperative to attain optimal drug effects and patient outcomes. The same is also true for older adults with decreased renal function, whether diagnosed with CKD or not.

In addition, patients with severe renal insufficiency, including those with CKD, may encounter accumulation of active metabolites, as well as accumulation of the parent drug compound. This can lead to significant toxicity in some cases. Examples of active metabolites include:

- Normeperidine, an active metabolite of meperidine that can lead to central nervous system stimulation including seizures;

- Morphine-6-glucuronide, an active metabolite of morphine and codeine with less analgesic effect. It can lead to a prolonged narcotic effect; or

- N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, a metabolite of acetaminophen responsible for hepatotoxicity.7

Doses of renally cleared drugs should be adjusted in patients with decreased renal function. Initial dosages can be determined using published guidelines.8 TH

Michele B. Kaufman is a freelance medical writer based in New York City.

References

- Quartarolo JM, Thoelke M, Schafers SJ. Reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: effect on physician recognition of chronic kidney disease and prescribing practices for elderly hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(2):74-78.

- Frye RF, Matzke GR. Drug therapy individualization for patients with renal insufficiency. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:939-952.

- Healthy Aging At-A-Glance 2007. Available at www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/healthy_aging.pdf. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Hanlon JT, Ruby CM, Guay D, et al. Geriatrics. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:79-89.

- Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(10):1917-1924.

- K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Available at www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm. Last accessed Oct. 15, 2007.

- Munar MY, Singh H. Drug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1487-1496.

- Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa : American College of Physicians; 2007.