User login

With the discovery of autoantibodies and other risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), researchers developed clinical trials to see whether the disease can be prevented entirely. In the past 10 years, a number of these trials have concluded, with variable results.

While some trials demonstrated no effect at all, others showed that medical intervention can delay the onset of disease in certain populations and even reduce the rates of progression to RA. These completed trials also offer researchers the chance to identify opportunities to improve RA prevention trials moving forward.

“We’re looking at all that data and trying to figure out what the next step is going to be,” said Kevin Deane, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine and a rheumatologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

Key lessons include the need for improved risk stratification tools and better understanding of RA pathogenesis, he said.

The Research So Far

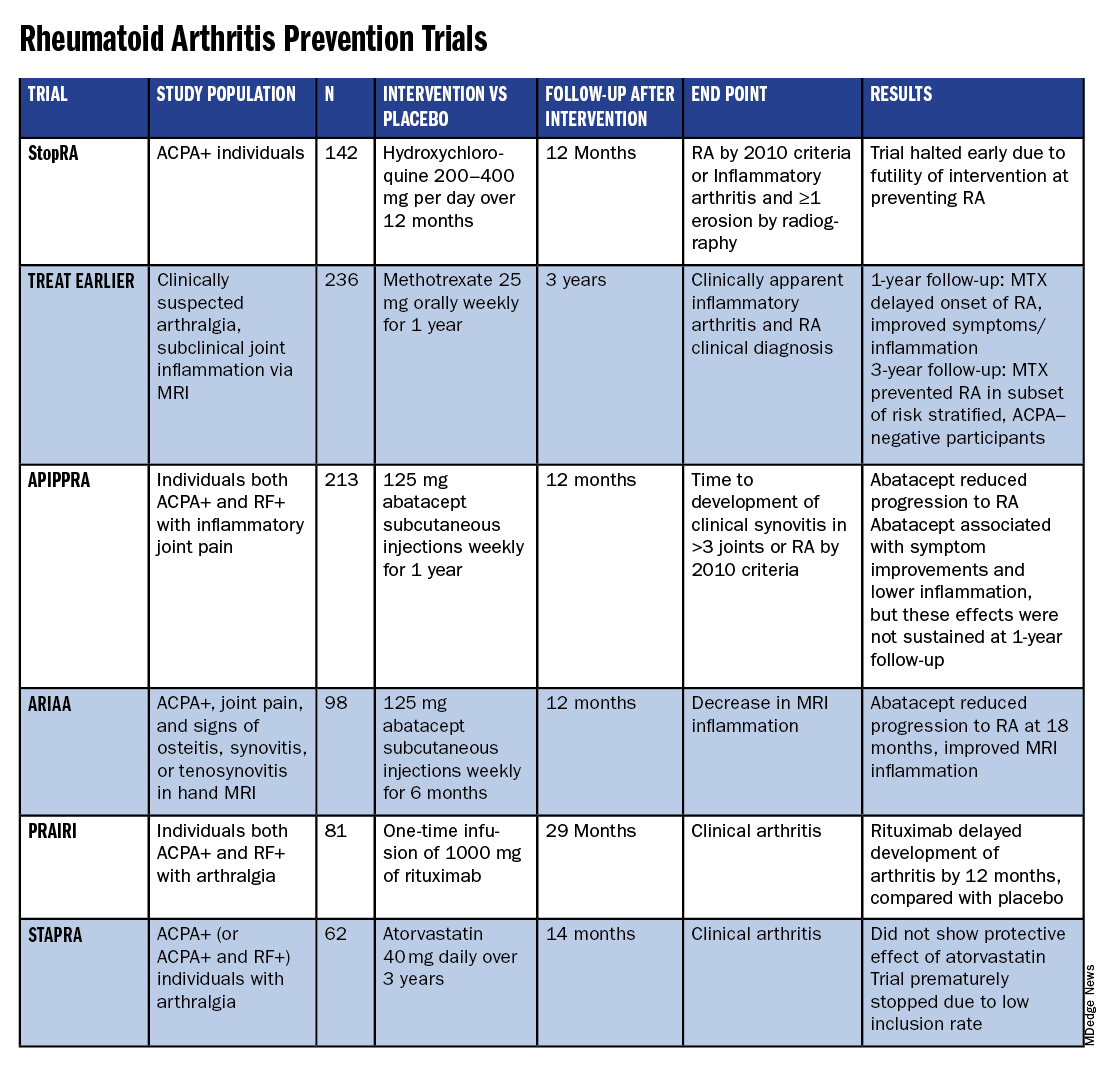

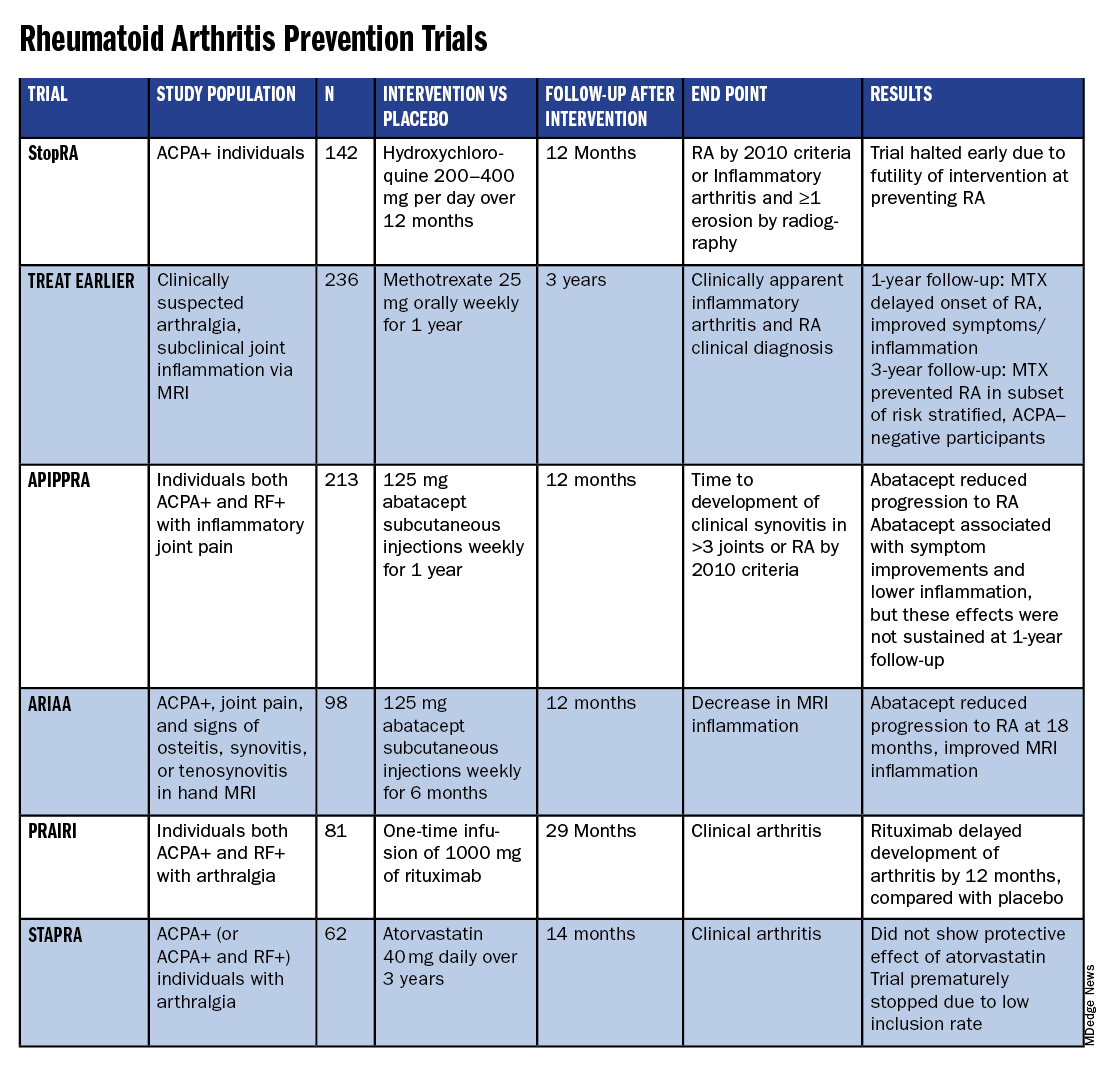

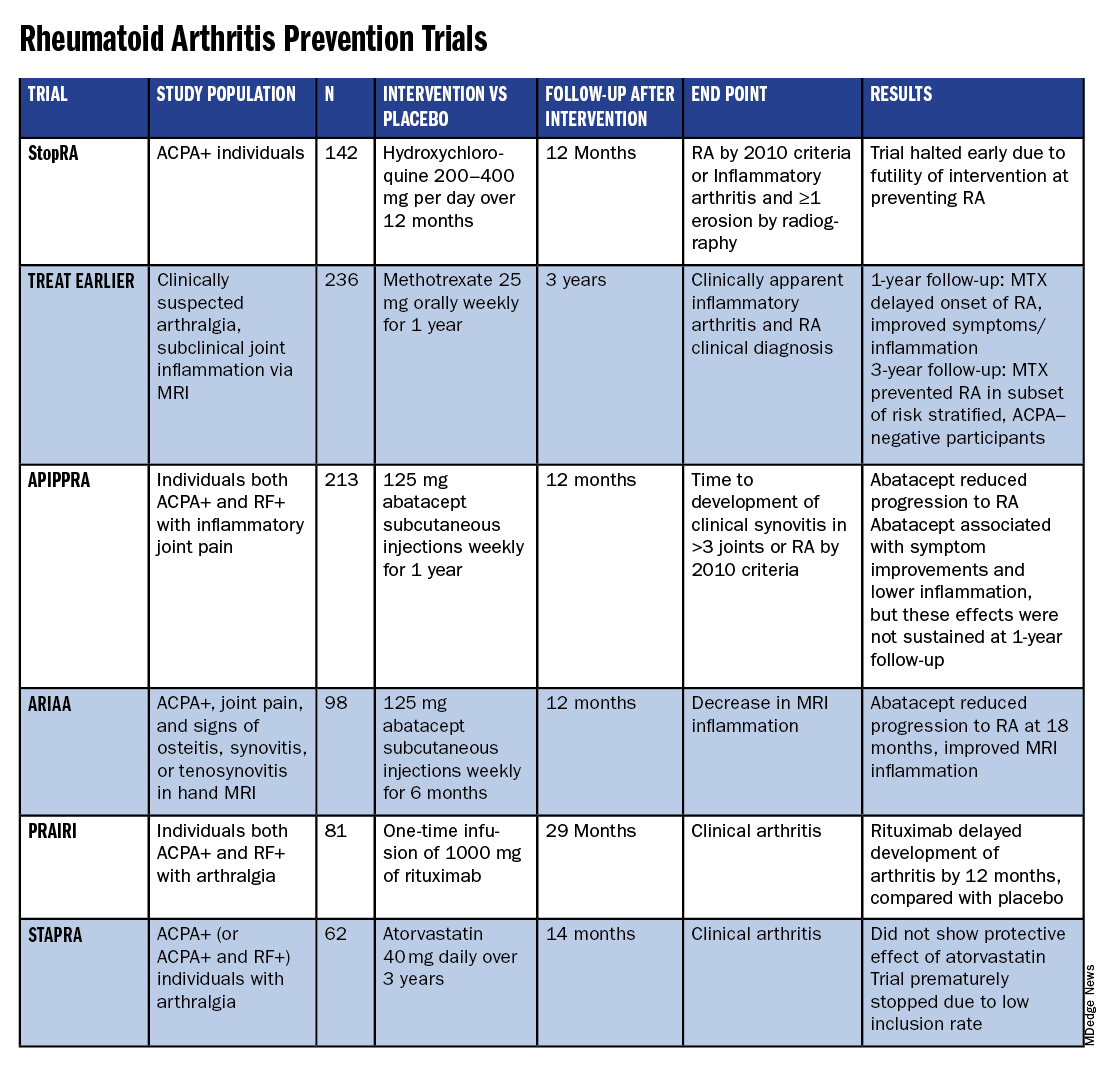

All RA prevention trials except for one have been completed and/or published within the past decade, bringing valuable insights to the field. (See chart below.)

Atorvastatin (STAPRA) and hydroxychloroquine (StopRA) proved ineffective in preventing the onset of RA, and both trials were stopped early. Rituximab and methotrexate (MTX) both delayed the onset of RA, but the effect disappeared by the end of the follow-up periods.

However, the 2-year results from the TREAT EARLIER trial showed that compared with patients given placebo, those given MTX showed improved MRI-detected joint inflammation, physical functioning, and reported symptoms.

The 4-year analysis of the trial further risk stratified participants and found that MTX showed a preventive effect in anti–citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)–negative participants at an increased risk for RA.

Abatacept also showed promise in preventing RA in two separate trials. In the ARIAA trial, compared with placebo, 6 months of treatment with abatacept reduced MRI inflammation and symptoms and lowered the rates of progression to RA. This treatment effect lessened during the 1-year follow-up period, but the difference between the two groups was still significant at 18 months.

In the APIPPRA trial, 12 months of treatment with abatacept improved subclinical inflammation and quality-of-life measures in participants and reduced the rates of progression to RA through another 12 months of observation. However, during this post-treatment follow-up period, the treatment effect began to diminish.

While there have been some promising findings — not only in disease prevention but also in disease modification — these studies all looked at different patient groups, noted Kulveer Mankia, MA, DM, an associate professor and consulting rheumatologist at the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Leeds in England.

“You have disparate, different inclusion criteria in different studies, all of which take years to complete,” he said. For example, while the TREAT EARLIER trial recruited patients with joint pain and subclinical joint inflammation via MRI, regardless of autoantibody status, the APIPPRA trial enrolled patients that were both ACPA+ and rheumatoid factor (RF)+ with joint pain.

“You’re left extrapolating as to whether [these interventions] will work in different at-risk populations,” he said.

Even with specific inclusion criteria in each study, there can still be heterogeneity in risk within a study group, Deane said. In the TREAT EARLIER study, 18%-20% of participants ultimately developed RA over the study period, which is lower than expected.

“While it seemed like a pretty high-risk group, it wasn’t as high risk as we thought,” he said, “and that’s why we’ve gone back to the drawing board.”

Risk Stratification Efforts

There are now two ongoing joint efforts by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) to define these populations and “bring some consensus to the field,” Mankia said.

The first aims to create a unanimous risk stratification tool for future RA prevention studies. The proposed system, devised for individuals with new joint symptoms who are at a risk for RA, was presented at the EULAR 2024 annual meeting and will be further discussed at the upcoming ACR 2024 annual meeting in Washington, DC.

The system uses a point system based on six criteria — three lab tests and three criteria commonly assessed in clinical practice:

- Morning stiffness

- Patient-reported joint swelling

- Difficulty making a fist

- Increased C-reactive protein

- RF positivity

- ACPA positivity

These criteria were picked so that the risk stratification tool can be used without imaging; however, the inclusion of MRI can further refine the score.

The ACR-EULAR task force that created the tool has emphasized that this criterion is specifically designed for research purposes and should not be used in clinical practice. Using this stratification tool should allow future clinical studies to group patients by similar risk, Deane said.

“Not that all studies have to look at exactly the same people, but each study should have similar risk stratification,” he said.

The second ACR-EULAR joint effort is taking a population-based approach to risk stratification, Deane said, to better predict RA risk in individuals without common symptoms like joint pain.

The aim is to create something analogous to the Framingham Risk Score in predicting cardiovascular disease, in which simple variables like total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and smoking status can be used to calculate an individual’s 10-year risk for CVD, Deane explained.

The second approach could also identify patients earlier in the progression to RA, which may be easier to treat than later stages of disease.

Understanding RA Origins

However, treating an earlier stage of disease might require a different approach. Up to this point, medical interventions for RA prevention used drugs approved to treat RA, but inventions during the pre-RA stage — before any joint symptoms appear — might require targeting different immunologic pathways.

“The general concept is if there is a pre-RA stage when joints are not involved, that means all the immunologic abnormalities are probably happening somewhere else in the body,” he said. “The big question is: Where is that, and how exactly is that happening?”

One theory is that RA begins to develop in mucosal sites, such as the intestines or lungs, before it involves synovial joints.

“In the absence of resolution, these localized immune processes transition into a systemic process that targets the joints, either by direct effects of microbiota, molecular mimicry, and/or immune amplification,” wrote Deane and coauthors in a recent review article in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. “This, in turn, leads to inappropriate engagement of a range of effector mechanisms in both synovium and periarticular sites.”

Following this logic, the progression of the at-risk stage of RA could be considered a continuum along which there are multiple possible points for intervention. It’s also probable that the disease can develop through multiple pathways, Deane said.

“If you look at all the people who get rheumatoid arthritis, there’s probably no way those could have the same exact pathways,” he said. “There’s probably going to be different endotypes and understanding that is going to help us prevent disease in a better way.”

Looking Forward

Beyond improving risk stratification and understanding RA pathogenesis, researchers are also considering novel therapeutic approaches for future trials. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists could be worth exploring in RA prevention and treatment, said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

These drugs — initially developed for diabetes — have already shown anti-inflammatory effects, and one study suggested that GLP-1s lowered the risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in individuals with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Obesity is a known risk factor for RA, so weight loss aided by GLP-1 drugs could also help reduce risk in certain patients. Clinical trials are needed to explore GLP-1s for both RA prevention and treatment, he said.

While prevention trials up to this point have used one-time, time-limited interventions, longer durations of medication or multiple rounds of therapy may be more efficacious. Even for trials that demonstrated the intervention arms had less progression to RA, this effect diminished once participants stopped the medication. In the ARIAA and APIPPRA trials using abatacept, “it wasn’t like we hit a reset button and [patients] just permanently now did not get rheumatoid arthritis,” Deane said, suggesting that alternative approaches should be explored.

“Future studies need to look at potentially longer doses of drug or lower doses of drug, or some combination that might be effective,” he said.

Deane received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Thermo Fisher, and Werfen and grant funding from Janssen Research and Development and Gilead Sciences. Mankia received grant support from Gilead, Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Serac Life Sciences and honoraria or consultant fees from AbbVie, UCB, Lilly, Galapagos, DeepCure, Serac Life Sciences, AstraZeneca, and Zura Bio. Sparks received research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Sonoma Biotherapeutics. He consulted for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Merck, Mustang, Optum, Pfizer, ReCor Medical, Sana, Sobi, and UCB.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the discovery of autoantibodies and other risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), researchers developed clinical trials to see whether the disease can be prevented entirely. In the past 10 years, a number of these trials have concluded, with variable results.

While some trials demonstrated no effect at all, others showed that medical intervention can delay the onset of disease in certain populations and even reduce the rates of progression to RA. These completed trials also offer researchers the chance to identify opportunities to improve RA prevention trials moving forward.

“We’re looking at all that data and trying to figure out what the next step is going to be,” said Kevin Deane, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine and a rheumatologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

Key lessons include the need for improved risk stratification tools and better understanding of RA pathogenesis, he said.

The Research So Far

All RA prevention trials except for one have been completed and/or published within the past decade, bringing valuable insights to the field. (See chart below.)

Atorvastatin (STAPRA) and hydroxychloroquine (StopRA) proved ineffective in preventing the onset of RA, and both trials were stopped early. Rituximab and methotrexate (MTX) both delayed the onset of RA, but the effect disappeared by the end of the follow-up periods.

However, the 2-year results from the TREAT EARLIER trial showed that compared with patients given placebo, those given MTX showed improved MRI-detected joint inflammation, physical functioning, and reported symptoms.

The 4-year analysis of the trial further risk stratified participants and found that MTX showed a preventive effect in anti–citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)–negative participants at an increased risk for RA.

Abatacept also showed promise in preventing RA in two separate trials. In the ARIAA trial, compared with placebo, 6 months of treatment with abatacept reduced MRI inflammation and symptoms and lowered the rates of progression to RA. This treatment effect lessened during the 1-year follow-up period, but the difference between the two groups was still significant at 18 months.

In the APIPPRA trial, 12 months of treatment with abatacept improved subclinical inflammation and quality-of-life measures in participants and reduced the rates of progression to RA through another 12 months of observation. However, during this post-treatment follow-up period, the treatment effect began to diminish.

While there have been some promising findings — not only in disease prevention but also in disease modification — these studies all looked at different patient groups, noted Kulveer Mankia, MA, DM, an associate professor and consulting rheumatologist at the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Leeds in England.

“You have disparate, different inclusion criteria in different studies, all of which take years to complete,” he said. For example, while the TREAT EARLIER trial recruited patients with joint pain and subclinical joint inflammation via MRI, regardless of autoantibody status, the APIPPRA trial enrolled patients that were both ACPA+ and rheumatoid factor (RF)+ with joint pain.

“You’re left extrapolating as to whether [these interventions] will work in different at-risk populations,” he said.

Even with specific inclusion criteria in each study, there can still be heterogeneity in risk within a study group, Deane said. In the TREAT EARLIER study, 18%-20% of participants ultimately developed RA over the study period, which is lower than expected.

“While it seemed like a pretty high-risk group, it wasn’t as high risk as we thought,” he said, “and that’s why we’ve gone back to the drawing board.”

Risk Stratification Efforts

There are now two ongoing joint efforts by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) to define these populations and “bring some consensus to the field,” Mankia said.

The first aims to create a unanimous risk stratification tool for future RA prevention studies. The proposed system, devised for individuals with new joint symptoms who are at a risk for RA, was presented at the EULAR 2024 annual meeting and will be further discussed at the upcoming ACR 2024 annual meeting in Washington, DC.

The system uses a point system based on six criteria — three lab tests and three criteria commonly assessed in clinical practice:

- Morning stiffness

- Patient-reported joint swelling

- Difficulty making a fist

- Increased C-reactive protein

- RF positivity

- ACPA positivity

These criteria were picked so that the risk stratification tool can be used without imaging; however, the inclusion of MRI can further refine the score.

The ACR-EULAR task force that created the tool has emphasized that this criterion is specifically designed for research purposes and should not be used in clinical practice. Using this stratification tool should allow future clinical studies to group patients by similar risk, Deane said.

“Not that all studies have to look at exactly the same people, but each study should have similar risk stratification,” he said.

The second ACR-EULAR joint effort is taking a population-based approach to risk stratification, Deane said, to better predict RA risk in individuals without common symptoms like joint pain.

The aim is to create something analogous to the Framingham Risk Score in predicting cardiovascular disease, in which simple variables like total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and smoking status can be used to calculate an individual’s 10-year risk for CVD, Deane explained.

The second approach could also identify patients earlier in the progression to RA, which may be easier to treat than later stages of disease.

Understanding RA Origins

However, treating an earlier stage of disease might require a different approach. Up to this point, medical interventions for RA prevention used drugs approved to treat RA, but inventions during the pre-RA stage — before any joint symptoms appear — might require targeting different immunologic pathways.

“The general concept is if there is a pre-RA stage when joints are not involved, that means all the immunologic abnormalities are probably happening somewhere else in the body,” he said. “The big question is: Where is that, and how exactly is that happening?”

One theory is that RA begins to develop in mucosal sites, such as the intestines or lungs, before it involves synovial joints.

“In the absence of resolution, these localized immune processes transition into a systemic process that targets the joints, either by direct effects of microbiota, molecular mimicry, and/or immune amplification,” wrote Deane and coauthors in a recent review article in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. “This, in turn, leads to inappropriate engagement of a range of effector mechanisms in both synovium and periarticular sites.”

Following this logic, the progression of the at-risk stage of RA could be considered a continuum along which there are multiple possible points for intervention. It’s also probable that the disease can develop through multiple pathways, Deane said.

“If you look at all the people who get rheumatoid arthritis, there’s probably no way those could have the same exact pathways,” he said. “There’s probably going to be different endotypes and understanding that is going to help us prevent disease in a better way.”

Looking Forward

Beyond improving risk stratification and understanding RA pathogenesis, researchers are also considering novel therapeutic approaches for future trials. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists could be worth exploring in RA prevention and treatment, said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

These drugs — initially developed for diabetes — have already shown anti-inflammatory effects, and one study suggested that GLP-1s lowered the risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in individuals with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Obesity is a known risk factor for RA, so weight loss aided by GLP-1 drugs could also help reduce risk in certain patients. Clinical trials are needed to explore GLP-1s for both RA prevention and treatment, he said.

While prevention trials up to this point have used one-time, time-limited interventions, longer durations of medication or multiple rounds of therapy may be more efficacious. Even for trials that demonstrated the intervention arms had less progression to RA, this effect diminished once participants stopped the medication. In the ARIAA and APIPPRA trials using abatacept, “it wasn’t like we hit a reset button and [patients] just permanently now did not get rheumatoid arthritis,” Deane said, suggesting that alternative approaches should be explored.

“Future studies need to look at potentially longer doses of drug or lower doses of drug, or some combination that might be effective,” he said.

Deane received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Thermo Fisher, and Werfen and grant funding from Janssen Research and Development and Gilead Sciences. Mankia received grant support from Gilead, Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Serac Life Sciences and honoraria or consultant fees from AbbVie, UCB, Lilly, Galapagos, DeepCure, Serac Life Sciences, AstraZeneca, and Zura Bio. Sparks received research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Sonoma Biotherapeutics. He consulted for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Merck, Mustang, Optum, Pfizer, ReCor Medical, Sana, Sobi, and UCB.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the discovery of autoantibodies and other risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), researchers developed clinical trials to see whether the disease can be prevented entirely. In the past 10 years, a number of these trials have concluded, with variable results.

While some trials demonstrated no effect at all, others showed that medical intervention can delay the onset of disease in certain populations and even reduce the rates of progression to RA. These completed trials also offer researchers the chance to identify opportunities to improve RA prevention trials moving forward.

“We’re looking at all that data and trying to figure out what the next step is going to be,” said Kevin Deane, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine and a rheumatologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

Key lessons include the need for improved risk stratification tools and better understanding of RA pathogenesis, he said.

The Research So Far

All RA prevention trials except for one have been completed and/or published within the past decade, bringing valuable insights to the field. (See chart below.)

Atorvastatin (STAPRA) and hydroxychloroquine (StopRA) proved ineffective in preventing the onset of RA, and both trials were stopped early. Rituximab and methotrexate (MTX) both delayed the onset of RA, but the effect disappeared by the end of the follow-up periods.

However, the 2-year results from the TREAT EARLIER trial showed that compared with patients given placebo, those given MTX showed improved MRI-detected joint inflammation, physical functioning, and reported symptoms.

The 4-year analysis of the trial further risk stratified participants and found that MTX showed a preventive effect in anti–citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)–negative participants at an increased risk for RA.

Abatacept also showed promise in preventing RA in two separate trials. In the ARIAA trial, compared with placebo, 6 months of treatment with abatacept reduced MRI inflammation and symptoms and lowered the rates of progression to RA. This treatment effect lessened during the 1-year follow-up period, but the difference between the two groups was still significant at 18 months.

In the APIPPRA trial, 12 months of treatment with abatacept improved subclinical inflammation and quality-of-life measures in participants and reduced the rates of progression to RA through another 12 months of observation. However, during this post-treatment follow-up period, the treatment effect began to diminish.

While there have been some promising findings — not only in disease prevention but also in disease modification — these studies all looked at different patient groups, noted Kulveer Mankia, MA, DM, an associate professor and consulting rheumatologist at the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Leeds in England.

“You have disparate, different inclusion criteria in different studies, all of which take years to complete,” he said. For example, while the TREAT EARLIER trial recruited patients with joint pain and subclinical joint inflammation via MRI, regardless of autoantibody status, the APIPPRA trial enrolled patients that were both ACPA+ and rheumatoid factor (RF)+ with joint pain.

“You’re left extrapolating as to whether [these interventions] will work in different at-risk populations,” he said.

Even with specific inclusion criteria in each study, there can still be heterogeneity in risk within a study group, Deane said. In the TREAT EARLIER study, 18%-20% of participants ultimately developed RA over the study period, which is lower than expected.

“While it seemed like a pretty high-risk group, it wasn’t as high risk as we thought,” he said, “and that’s why we’ve gone back to the drawing board.”

Risk Stratification Efforts

There are now two ongoing joint efforts by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) to define these populations and “bring some consensus to the field,” Mankia said.

The first aims to create a unanimous risk stratification tool for future RA prevention studies. The proposed system, devised for individuals with new joint symptoms who are at a risk for RA, was presented at the EULAR 2024 annual meeting and will be further discussed at the upcoming ACR 2024 annual meeting in Washington, DC.

The system uses a point system based on six criteria — three lab tests and three criteria commonly assessed in clinical practice:

- Morning stiffness

- Patient-reported joint swelling

- Difficulty making a fist

- Increased C-reactive protein

- RF positivity

- ACPA positivity

These criteria were picked so that the risk stratification tool can be used without imaging; however, the inclusion of MRI can further refine the score.

The ACR-EULAR task force that created the tool has emphasized that this criterion is specifically designed for research purposes and should not be used in clinical practice. Using this stratification tool should allow future clinical studies to group patients by similar risk, Deane said.

“Not that all studies have to look at exactly the same people, but each study should have similar risk stratification,” he said.

The second ACR-EULAR joint effort is taking a population-based approach to risk stratification, Deane said, to better predict RA risk in individuals without common symptoms like joint pain.

The aim is to create something analogous to the Framingham Risk Score in predicting cardiovascular disease, in which simple variables like total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and smoking status can be used to calculate an individual’s 10-year risk for CVD, Deane explained.

The second approach could also identify patients earlier in the progression to RA, which may be easier to treat than later stages of disease.

Understanding RA Origins

However, treating an earlier stage of disease might require a different approach. Up to this point, medical interventions for RA prevention used drugs approved to treat RA, but inventions during the pre-RA stage — before any joint symptoms appear — might require targeting different immunologic pathways.

“The general concept is if there is a pre-RA stage when joints are not involved, that means all the immunologic abnormalities are probably happening somewhere else in the body,” he said. “The big question is: Where is that, and how exactly is that happening?”

One theory is that RA begins to develop in mucosal sites, such as the intestines or lungs, before it involves synovial joints.

“In the absence of resolution, these localized immune processes transition into a systemic process that targets the joints, either by direct effects of microbiota, molecular mimicry, and/or immune amplification,” wrote Deane and coauthors in a recent review article in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. “This, in turn, leads to inappropriate engagement of a range of effector mechanisms in both synovium and periarticular sites.”

Following this logic, the progression of the at-risk stage of RA could be considered a continuum along which there are multiple possible points for intervention. It’s also probable that the disease can develop through multiple pathways, Deane said.

“If you look at all the people who get rheumatoid arthritis, there’s probably no way those could have the same exact pathways,” he said. “There’s probably going to be different endotypes and understanding that is going to help us prevent disease in a better way.”

Looking Forward

Beyond improving risk stratification and understanding RA pathogenesis, researchers are also considering novel therapeutic approaches for future trials. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists could be worth exploring in RA prevention and treatment, said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

These drugs — initially developed for diabetes — have already shown anti-inflammatory effects, and one study suggested that GLP-1s lowered the risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in individuals with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Obesity is a known risk factor for RA, so weight loss aided by GLP-1 drugs could also help reduce risk in certain patients. Clinical trials are needed to explore GLP-1s for both RA prevention and treatment, he said.

While prevention trials up to this point have used one-time, time-limited interventions, longer durations of medication or multiple rounds of therapy may be more efficacious. Even for trials that demonstrated the intervention arms had less progression to RA, this effect diminished once participants stopped the medication. In the ARIAA and APIPPRA trials using abatacept, “it wasn’t like we hit a reset button and [patients] just permanently now did not get rheumatoid arthritis,” Deane said, suggesting that alternative approaches should be explored.

“Future studies need to look at potentially longer doses of drug or lower doses of drug, or some combination that might be effective,” he said.

Deane received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Thermo Fisher, and Werfen and grant funding from Janssen Research and Development and Gilead Sciences. Mankia received grant support from Gilead, Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Serac Life Sciences and honoraria or consultant fees from AbbVie, UCB, Lilly, Galapagos, DeepCure, Serac Life Sciences, AstraZeneca, and Zura Bio. Sparks received research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Sonoma Biotherapeutics. He consulted for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Merck, Mustang, Optum, Pfizer, ReCor Medical, Sana, Sobi, and UCB.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.