User login

In the United States, 31 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam have legalized medical marijuana, which is also permitted for recreational use in 9 states, as well as in the District of Columbia. However, marijuana, derived from Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, is regulated as a schedule I drug in the United States at the federal level. (Some believe that the federal status may change in the coming year as a result of the Democratic Party’s takeover in the House of Representatives.1)

Cannabis species contain hundreds of various substances, of which the cannabinoids are the most studied. More than 113 biologically active chemical compounds are found within the class of cannabinoids and their derivatives,2 which have been used for centuries in natural medicine.3 The legal status of marijuana has long hampered scientific research of cannabinoids. Nevertheless, the number of studies focusing on the therapeutic potential of these compounds has steadily risen as the legal landscape of marijuana has evolved.

Findings over the last 20 years have shown that cannabinoids present in C. sativa exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and suppress the proliferation of multiple tumorigenic cell lines, some of which are moderated through cannabinoid (CB) receptors.4 In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, .3 Recent research has demonstrated that CB receptors are present in human skin.4

The endocannabinoid system has emerged as an intriguing area of research, as we’ve come to learn about its convoluted role in human anatomy and health. It features a pervasive network of endogenous ligands, enzymes, and receptors, which exogenous substances (including phytocannabinoids and synthetic cannabinoids) can activate.5 Data from recent studies indicate that the endocannabinoid system plays a significant role in cutaneous homeostasis, as it regulates proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory mediator release.5 Further, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, and wound healing have been identified in recent research as cutaneous concerns in which the use of cannabinoids may be of benefit.6,7 We must also consider reports that cannabinoids can slow human hair growth and that some constituents may spur the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines.8,9This column will briefly address potential confusion over the psychoactive aspects of cannabis, which are related to particular constituents of cannabis and specific CB receptors, and focus on the endocannabinoid system.

Psychoactive or not?

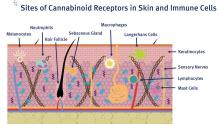

C. sativa confers biological activity through its influence on the G-protein-coupled receptor types CB1 and CB2,10 which pervade human skin epithelium.11 CB1 receptors are found in greatest supply in the central nervous system, especially the basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, where their activation yields psychoactivity.2,5,12,13 Stimulation of CB1 receptors in the skin – where they are present in differentiated keratinocytes, hair follicle cells, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons14 – diminishes pain and pruritus, controls keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, inhibits hair follicle growth, and regulates the release of damage-induced keratins and inflammatory mediators to maintain cutaneous homeostasis.11,14,15

CB2 receptors are expressed in the immune system, particularly monocytes, macrophages, as well as B and T cells, and in peripheral tissues including the spleen, tonsils, thymus gland, bone, and, notably, the skin.2,16 Stimulation of CB2 receptors in the skin – where they are found in keratinocytes, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons – fosters sebum production, regulates pain sensation, hinders keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, and suppresses cutaneous inflammatory responses.14,15

The best known, or most notorious, component of exogenous cannabinoids is delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta9-THC or simply THC), which is a natural psychoactive constituent in marijuana.3 In fact, of the five primary cannabinoids derived from marijuana, including cannabidiol (CBD), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and THC, only THC imparts psychoactive effects.17

CBD is thought to exhibit anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities.18 THC has been found to have the capacity to induce cancer cell apoptosis and block angiogenesis,19 and is thought to have immunomodulatory potential, partly acting through the G-protein-coupled CB1 and CB2 receptors but also yielding effects not related to these receptors.20In a 2014 survey of medical cannabis users, a statistically significant preference for C. indica (which contains higher CBD and lower THC levels) was observed for pain management, sedation, and sleep, while C. sativa was associated with euphoria and improving energy.21

The endocannabinoid system and skin health

The endogenous cannabinoid or endocannabinoid system includes cannabinoid receptors, associated endogenous ligands (such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide [anandamide or AEA], 2-arachidonoyl glycerol [2-AG], and N-palmitoylethanolamide [PEA], a fatty acid amide that enhances AEA activity),2 and enzymes involved in endocannabinoid production and decay.11,15,22,23 Research in recent years appears to support the notion that the endocannabinoid system plays an important role in skin health, as its dysregulation has been linked to atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, scleroderma, and skin cancer. Data indicate that exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids influence the endocannabinoid system through cannabinoid receptors, transient receptor potential channels (TRPs), and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs). Río et al. suggest that the dynamism of the endocannabinoid system buttresses the targeting of multiple endpoints for therapeutic success with cannabinoids rather than the one-disease-one-target approach.24 Endogenous cannabinoids, such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, are now thought to be significant mediators in the skin.3 Further, endocannabinoids have been shown to deliver analgesia to the skin, at the spinal and supraspinal levels.25

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Tubaro et al. used the Croton oil mouse ear dermatitis assay to study the in vivo topical anti-inflammatory effects of seven phytocannabinoids and their related cannabivarins (nonpsychoactive cannabinoids). They found that anti-inflammatory activity was derived from the involvement of the cannabinoid receptors as well as the inflammatory endpoints that the phytocannabinoids targeted.26

In 2013, Gaffal et al. explored the anti-inflammatory activity of topical THC in dinitrofluorobenzene-mediated allergic contact dermatitis independent of CB1/2 receptors by using wild-type and CB1/2 receptor-deficient mice. The researchers found that topically applied THC reduced contact allergic ear edema and myeloid immune cell infiltration in both groups of mice. They concluded that such a decline in inflammation resulted from mitigating the keratinocyte-derived proinflammatory mediators that direct myeloid immune cell infiltration independent of CB1/2 receptors, and positions cannabinoids well for future use in treating inflammatory cutaneous conditions.20

Literature reviews

In a 2018 literature review on the uses of cannabinoids for cutaneous disorders, Eagleston et al. determined that preclinical data on cannabinoids reveal the potential to treat acne, allergic contact dermatitis, asteatotic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Kaposi sarcoma, pruritus, psoriasis, skin cancer, and the skin symptoms of systemic sclerosis. They caution, though, that more preclinical work is necessary along with randomized, controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes to establish the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids to treat skin conditions.27

A literature review by Marks and Friedman published later that year on the therapeutic potential of phytocannabinoids, endocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids in managing skin disorders revealed the same findings regarding the cutaneous conditions associated with these compounds. The authors noted, though, that while the preponderance of articles highlight the efficacy of cannabinoids in treating inflammatory and neoplastic cutaneous conditions, some reports indicate proinflammatory and proneoplastic activities of cannabinoids. Like Eagleston et al., they call for additional studies.28

Conclusion

As in many botanical agents that I cover in this column, cannabis is associated with numerous medical benefits. I am encouraged to see expanding legalization of medical marijuana and increased research into its reputedly broad potential to improve human health. Anecdotally, I have heard stunning reports from patients about amelioration of joint and back pain as well as relief from other inflammatory symptoms. Discovery and elucidation of the endogenous cannabinoid system is a recent development. Research on its functions and roles in cutaneous health has followed suit and is steadily increasing. Particular skin conditions for which cannabis and cannabinoids may be indicated will be the focus of the next column.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com

References

1. Higdon J. Why 2019 could be marijuana’s biggest year yet. Politico Magazine. Jan 21, 2019.

2. Singh D et al. Clin Dermatol. 2018 May-Jun;36(3):399-419.

3. Kupczyk P et al. Exp Dermatol. 2009 Aug;18(8):669-79.

4. Wilkinson JD et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2007 Feb;45(2):87-92.

5. Milando R et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 April;20(2):167-80.

6. Robinson E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Dec 1;17(12):1273-8.

7. Mounessa JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jul;77(1):188-90.

8. Liszewski W et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77(3):e87-e88.

9. Telek A et al. FASEB J. 2007 Nov;21(13):3534-41.

10. Wollenberg A et al. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jul;170 Suppl 1:7-11.

11. Ramot Y et al. PeerJ. 2013 Feb 19;1:e40.

12. Schlicker E et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Nov;22(11):565-72.

13. Christie MJ et al. Nature. 2001 Mar 29;410(6828):527-30.

14. Ibid.

15. Bíró T et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009 Aug;30(8):411-20.

16. Pacher P et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2006 Sep;58(3):389-462.

17. Shalaby M et al. Pract Dermatol. 2018 Jan;68-70.

18. Chelliah MP et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):e224-e227.

19. Glodde N et al. Life Sci. 2015 Oct 1;138:35-40.

20. Gaffal E et al. Allergy. 2013 Aug;68(8):994-1000.

21. Pearce DD et al. J Altern Complement Med. 2014 Oct;20(10):787:91.

22. Leonti M et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Jun 15;79(12):1815-26.

23. Trusler AR et al. Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28(1):22-32.

24. Río CD et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 Nov;157:122-133.

25. Chuquilin M et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Feb;74(2):197-212.

26. Tubaro A et al. Fitoterapia. 2010 Oct;81(7):816-9.

27. Eagleston LRM et al. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jun 15;24(6).

28. Marks DH et al. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018 Nov;23(6):1-5.

In the United States, 31 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam have legalized medical marijuana, which is also permitted for recreational use in 9 states, as well as in the District of Columbia. However, marijuana, derived from Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, is regulated as a schedule I drug in the United States at the federal level. (Some believe that the federal status may change in the coming year as a result of the Democratic Party’s takeover in the House of Representatives.1)

Cannabis species contain hundreds of various substances, of which the cannabinoids are the most studied. More than 113 biologically active chemical compounds are found within the class of cannabinoids and their derivatives,2 which have been used for centuries in natural medicine.3 The legal status of marijuana has long hampered scientific research of cannabinoids. Nevertheless, the number of studies focusing on the therapeutic potential of these compounds has steadily risen as the legal landscape of marijuana has evolved.

Findings over the last 20 years have shown that cannabinoids present in C. sativa exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and suppress the proliferation of multiple tumorigenic cell lines, some of which are moderated through cannabinoid (CB) receptors.4 In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, .3 Recent research has demonstrated that CB receptors are present in human skin.4

The endocannabinoid system has emerged as an intriguing area of research, as we’ve come to learn about its convoluted role in human anatomy and health. It features a pervasive network of endogenous ligands, enzymes, and receptors, which exogenous substances (including phytocannabinoids and synthetic cannabinoids) can activate.5 Data from recent studies indicate that the endocannabinoid system plays a significant role in cutaneous homeostasis, as it regulates proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory mediator release.5 Further, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, and wound healing have been identified in recent research as cutaneous concerns in which the use of cannabinoids may be of benefit.6,7 We must also consider reports that cannabinoids can slow human hair growth and that some constituents may spur the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines.8,9This column will briefly address potential confusion over the psychoactive aspects of cannabis, which are related to particular constituents of cannabis and specific CB receptors, and focus on the endocannabinoid system.

Psychoactive or not?

C. sativa confers biological activity through its influence on the G-protein-coupled receptor types CB1 and CB2,10 which pervade human skin epithelium.11 CB1 receptors are found in greatest supply in the central nervous system, especially the basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, where their activation yields psychoactivity.2,5,12,13 Stimulation of CB1 receptors in the skin – where they are present in differentiated keratinocytes, hair follicle cells, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons14 – diminishes pain and pruritus, controls keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, inhibits hair follicle growth, and regulates the release of damage-induced keratins and inflammatory mediators to maintain cutaneous homeostasis.11,14,15

CB2 receptors are expressed in the immune system, particularly monocytes, macrophages, as well as B and T cells, and in peripheral tissues including the spleen, tonsils, thymus gland, bone, and, notably, the skin.2,16 Stimulation of CB2 receptors in the skin – where they are found in keratinocytes, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons – fosters sebum production, regulates pain sensation, hinders keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, and suppresses cutaneous inflammatory responses.14,15

The best known, or most notorious, component of exogenous cannabinoids is delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta9-THC or simply THC), which is a natural psychoactive constituent in marijuana.3 In fact, of the five primary cannabinoids derived from marijuana, including cannabidiol (CBD), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and THC, only THC imparts psychoactive effects.17

CBD is thought to exhibit anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities.18 THC has been found to have the capacity to induce cancer cell apoptosis and block angiogenesis,19 and is thought to have immunomodulatory potential, partly acting through the G-protein-coupled CB1 and CB2 receptors but also yielding effects not related to these receptors.20In a 2014 survey of medical cannabis users, a statistically significant preference for C. indica (which contains higher CBD and lower THC levels) was observed for pain management, sedation, and sleep, while C. sativa was associated with euphoria and improving energy.21

The endocannabinoid system and skin health

The endogenous cannabinoid or endocannabinoid system includes cannabinoid receptors, associated endogenous ligands (such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide [anandamide or AEA], 2-arachidonoyl glycerol [2-AG], and N-palmitoylethanolamide [PEA], a fatty acid amide that enhances AEA activity),2 and enzymes involved in endocannabinoid production and decay.11,15,22,23 Research in recent years appears to support the notion that the endocannabinoid system plays an important role in skin health, as its dysregulation has been linked to atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, scleroderma, and skin cancer. Data indicate that exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids influence the endocannabinoid system through cannabinoid receptors, transient receptor potential channels (TRPs), and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs). Río et al. suggest that the dynamism of the endocannabinoid system buttresses the targeting of multiple endpoints for therapeutic success with cannabinoids rather than the one-disease-one-target approach.24 Endogenous cannabinoids, such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, are now thought to be significant mediators in the skin.3 Further, endocannabinoids have been shown to deliver analgesia to the skin, at the spinal and supraspinal levels.25

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Tubaro et al. used the Croton oil mouse ear dermatitis assay to study the in vivo topical anti-inflammatory effects of seven phytocannabinoids and their related cannabivarins (nonpsychoactive cannabinoids). They found that anti-inflammatory activity was derived from the involvement of the cannabinoid receptors as well as the inflammatory endpoints that the phytocannabinoids targeted.26

In 2013, Gaffal et al. explored the anti-inflammatory activity of topical THC in dinitrofluorobenzene-mediated allergic contact dermatitis independent of CB1/2 receptors by using wild-type and CB1/2 receptor-deficient mice. The researchers found that topically applied THC reduced contact allergic ear edema and myeloid immune cell infiltration in both groups of mice. They concluded that such a decline in inflammation resulted from mitigating the keratinocyte-derived proinflammatory mediators that direct myeloid immune cell infiltration independent of CB1/2 receptors, and positions cannabinoids well for future use in treating inflammatory cutaneous conditions.20

Literature reviews

In a 2018 literature review on the uses of cannabinoids for cutaneous disorders, Eagleston et al. determined that preclinical data on cannabinoids reveal the potential to treat acne, allergic contact dermatitis, asteatotic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Kaposi sarcoma, pruritus, psoriasis, skin cancer, and the skin symptoms of systemic sclerosis. They caution, though, that more preclinical work is necessary along with randomized, controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes to establish the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids to treat skin conditions.27

A literature review by Marks and Friedman published later that year on the therapeutic potential of phytocannabinoids, endocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids in managing skin disorders revealed the same findings regarding the cutaneous conditions associated with these compounds. The authors noted, though, that while the preponderance of articles highlight the efficacy of cannabinoids in treating inflammatory and neoplastic cutaneous conditions, some reports indicate proinflammatory and proneoplastic activities of cannabinoids. Like Eagleston et al., they call for additional studies.28

Conclusion

As in many botanical agents that I cover in this column, cannabis is associated with numerous medical benefits. I am encouraged to see expanding legalization of medical marijuana and increased research into its reputedly broad potential to improve human health. Anecdotally, I have heard stunning reports from patients about amelioration of joint and back pain as well as relief from other inflammatory symptoms. Discovery and elucidation of the endogenous cannabinoid system is a recent development. Research on its functions and roles in cutaneous health has followed suit and is steadily increasing. Particular skin conditions for which cannabis and cannabinoids may be indicated will be the focus of the next column.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com

References

1. Higdon J. Why 2019 could be marijuana’s biggest year yet. Politico Magazine. Jan 21, 2019.

2. Singh D et al. Clin Dermatol. 2018 May-Jun;36(3):399-419.

3. Kupczyk P et al. Exp Dermatol. 2009 Aug;18(8):669-79.

4. Wilkinson JD et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2007 Feb;45(2):87-92.

5. Milando R et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 April;20(2):167-80.

6. Robinson E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Dec 1;17(12):1273-8.

7. Mounessa JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jul;77(1):188-90.

8. Liszewski W et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77(3):e87-e88.

9. Telek A et al. FASEB J. 2007 Nov;21(13):3534-41.

10. Wollenberg A et al. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jul;170 Suppl 1:7-11.

11. Ramot Y et al. PeerJ. 2013 Feb 19;1:e40.

12. Schlicker E et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Nov;22(11):565-72.

13. Christie MJ et al. Nature. 2001 Mar 29;410(6828):527-30.

14. Ibid.

15. Bíró T et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009 Aug;30(8):411-20.

16. Pacher P et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2006 Sep;58(3):389-462.

17. Shalaby M et al. Pract Dermatol. 2018 Jan;68-70.

18. Chelliah MP et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):e224-e227.

19. Glodde N et al. Life Sci. 2015 Oct 1;138:35-40.

20. Gaffal E et al. Allergy. 2013 Aug;68(8):994-1000.

21. Pearce DD et al. J Altern Complement Med. 2014 Oct;20(10):787:91.

22. Leonti M et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Jun 15;79(12):1815-26.

23. Trusler AR et al. Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28(1):22-32.

24. Río CD et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 Nov;157:122-133.

25. Chuquilin M et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Feb;74(2):197-212.

26. Tubaro A et al. Fitoterapia. 2010 Oct;81(7):816-9.

27. Eagleston LRM et al. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jun 15;24(6).

28. Marks DH et al. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018 Nov;23(6):1-5.

In the United States, 31 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam have legalized medical marijuana, which is also permitted for recreational use in 9 states, as well as in the District of Columbia. However, marijuana, derived from Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, is regulated as a schedule I drug in the United States at the federal level. (Some believe that the federal status may change in the coming year as a result of the Democratic Party’s takeover in the House of Representatives.1)

Cannabis species contain hundreds of various substances, of which the cannabinoids are the most studied. More than 113 biologically active chemical compounds are found within the class of cannabinoids and their derivatives,2 which have been used for centuries in natural medicine.3 The legal status of marijuana has long hampered scientific research of cannabinoids. Nevertheless, the number of studies focusing on the therapeutic potential of these compounds has steadily risen as the legal landscape of marijuana has evolved.

Findings over the last 20 years have shown that cannabinoids present in C. sativa exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and suppress the proliferation of multiple tumorigenic cell lines, some of which are moderated through cannabinoid (CB) receptors.4 In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, .3 Recent research has demonstrated that CB receptors are present in human skin.4

The endocannabinoid system has emerged as an intriguing area of research, as we’ve come to learn about its convoluted role in human anatomy and health. It features a pervasive network of endogenous ligands, enzymes, and receptors, which exogenous substances (including phytocannabinoids and synthetic cannabinoids) can activate.5 Data from recent studies indicate that the endocannabinoid system plays a significant role in cutaneous homeostasis, as it regulates proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory mediator release.5 Further, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, and wound healing have been identified in recent research as cutaneous concerns in which the use of cannabinoids may be of benefit.6,7 We must also consider reports that cannabinoids can slow human hair growth and that some constituents may spur the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines.8,9This column will briefly address potential confusion over the psychoactive aspects of cannabis, which are related to particular constituents of cannabis and specific CB receptors, and focus on the endocannabinoid system.

Psychoactive or not?

C. sativa confers biological activity through its influence on the G-protein-coupled receptor types CB1 and CB2,10 which pervade human skin epithelium.11 CB1 receptors are found in greatest supply in the central nervous system, especially the basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, where their activation yields psychoactivity.2,5,12,13 Stimulation of CB1 receptors in the skin – where they are present in differentiated keratinocytes, hair follicle cells, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons14 – diminishes pain and pruritus, controls keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, inhibits hair follicle growth, and regulates the release of damage-induced keratins and inflammatory mediators to maintain cutaneous homeostasis.11,14,15

CB2 receptors are expressed in the immune system, particularly monocytes, macrophages, as well as B and T cells, and in peripheral tissues including the spleen, tonsils, thymus gland, bone, and, notably, the skin.2,16 Stimulation of CB2 receptors in the skin – where they are found in keratinocytes, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons – fosters sebum production, regulates pain sensation, hinders keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, and suppresses cutaneous inflammatory responses.14,15

The best known, or most notorious, component of exogenous cannabinoids is delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta9-THC or simply THC), which is a natural psychoactive constituent in marijuana.3 In fact, of the five primary cannabinoids derived from marijuana, including cannabidiol (CBD), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and THC, only THC imparts psychoactive effects.17

CBD is thought to exhibit anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities.18 THC has been found to have the capacity to induce cancer cell apoptosis and block angiogenesis,19 and is thought to have immunomodulatory potential, partly acting through the G-protein-coupled CB1 and CB2 receptors but also yielding effects not related to these receptors.20In a 2014 survey of medical cannabis users, a statistically significant preference for C. indica (which contains higher CBD and lower THC levels) was observed for pain management, sedation, and sleep, while C. sativa was associated with euphoria and improving energy.21

The endocannabinoid system and skin health

The endogenous cannabinoid or endocannabinoid system includes cannabinoid receptors, associated endogenous ligands (such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide [anandamide or AEA], 2-arachidonoyl glycerol [2-AG], and N-palmitoylethanolamide [PEA], a fatty acid amide that enhances AEA activity),2 and enzymes involved in endocannabinoid production and decay.11,15,22,23 Research in recent years appears to support the notion that the endocannabinoid system plays an important role in skin health, as its dysregulation has been linked to atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, scleroderma, and skin cancer. Data indicate that exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids influence the endocannabinoid system through cannabinoid receptors, transient receptor potential channels (TRPs), and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs). Río et al. suggest that the dynamism of the endocannabinoid system buttresses the targeting of multiple endpoints for therapeutic success with cannabinoids rather than the one-disease-one-target approach.24 Endogenous cannabinoids, such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, are now thought to be significant mediators in the skin.3 Further, endocannabinoids have been shown to deliver analgesia to the skin, at the spinal and supraspinal levels.25

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Tubaro et al. used the Croton oil mouse ear dermatitis assay to study the in vivo topical anti-inflammatory effects of seven phytocannabinoids and their related cannabivarins (nonpsychoactive cannabinoids). They found that anti-inflammatory activity was derived from the involvement of the cannabinoid receptors as well as the inflammatory endpoints that the phytocannabinoids targeted.26

In 2013, Gaffal et al. explored the anti-inflammatory activity of topical THC in dinitrofluorobenzene-mediated allergic contact dermatitis independent of CB1/2 receptors by using wild-type and CB1/2 receptor-deficient mice. The researchers found that topically applied THC reduced contact allergic ear edema and myeloid immune cell infiltration in both groups of mice. They concluded that such a decline in inflammation resulted from mitigating the keratinocyte-derived proinflammatory mediators that direct myeloid immune cell infiltration independent of CB1/2 receptors, and positions cannabinoids well for future use in treating inflammatory cutaneous conditions.20

Literature reviews

In a 2018 literature review on the uses of cannabinoids for cutaneous disorders, Eagleston et al. determined that preclinical data on cannabinoids reveal the potential to treat acne, allergic contact dermatitis, asteatotic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Kaposi sarcoma, pruritus, psoriasis, skin cancer, and the skin symptoms of systemic sclerosis. They caution, though, that more preclinical work is necessary along with randomized, controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes to establish the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids to treat skin conditions.27

A literature review by Marks and Friedman published later that year on the therapeutic potential of phytocannabinoids, endocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids in managing skin disorders revealed the same findings regarding the cutaneous conditions associated with these compounds. The authors noted, though, that while the preponderance of articles highlight the efficacy of cannabinoids in treating inflammatory and neoplastic cutaneous conditions, some reports indicate proinflammatory and proneoplastic activities of cannabinoids. Like Eagleston et al., they call for additional studies.28

Conclusion

As in many botanical agents that I cover in this column, cannabis is associated with numerous medical benefits. I am encouraged to see expanding legalization of medical marijuana and increased research into its reputedly broad potential to improve human health. Anecdotally, I have heard stunning reports from patients about amelioration of joint and back pain as well as relief from other inflammatory symptoms. Discovery and elucidation of the endogenous cannabinoid system is a recent development. Research on its functions and roles in cutaneous health has followed suit and is steadily increasing. Particular skin conditions for which cannabis and cannabinoids may be indicated will be the focus of the next column.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com

References

1. Higdon J. Why 2019 could be marijuana’s biggest year yet. Politico Magazine. Jan 21, 2019.

2. Singh D et al. Clin Dermatol. 2018 May-Jun;36(3):399-419.

3. Kupczyk P et al. Exp Dermatol. 2009 Aug;18(8):669-79.

4. Wilkinson JD et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2007 Feb;45(2):87-92.

5. Milando R et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 April;20(2):167-80.

6. Robinson E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Dec 1;17(12):1273-8.

7. Mounessa JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jul;77(1):188-90.

8. Liszewski W et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77(3):e87-e88.

9. Telek A et al. FASEB J. 2007 Nov;21(13):3534-41.

10. Wollenberg A et al. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jul;170 Suppl 1:7-11.

11. Ramot Y et al. PeerJ. 2013 Feb 19;1:e40.

12. Schlicker E et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Nov;22(11):565-72.

13. Christie MJ et al. Nature. 2001 Mar 29;410(6828):527-30.

14. Ibid.

15. Bíró T et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009 Aug;30(8):411-20.

16. Pacher P et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2006 Sep;58(3):389-462.

17. Shalaby M et al. Pract Dermatol. 2018 Jan;68-70.

18. Chelliah MP et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):e224-e227.

19. Glodde N et al. Life Sci. 2015 Oct 1;138:35-40.

20. Gaffal E et al. Allergy. 2013 Aug;68(8):994-1000.

21. Pearce DD et al. J Altern Complement Med. 2014 Oct;20(10):787:91.

22. Leonti M et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Jun 15;79(12):1815-26.

23. Trusler AR et al. Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28(1):22-32.

24. Río CD et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 Nov;157:122-133.

25. Chuquilin M et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Feb;74(2):197-212.

26. Tubaro A et al. Fitoterapia. 2010 Oct;81(7):816-9.

27. Eagleston LRM et al. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jun 15;24(6).

28. Marks DH et al. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018 Nov;23(6):1-5.