User login

Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, vividly recalls the moment when he realized “scope creep” had become a problem. A hospitalist partner who was working a night shift admitted a young man who had been in a high-speed motor vehicle accident. The hospitalist did so because the general surgeon did not want to come into the hospital.

Dr. Siegal, currently the medical director of critical-care medicine at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, remembers looking at his partner and asking, “What the hell are you doing admitting a trauma patient? You’re an internist!”

Dr. Siegal’s partner responded, “I’m just trying to show value.”

“That was an ‘a-ha’ moment for me,” says Dr. Siegal, a member of SHM’s board of directors. It was at that point he began to understand that the expansion strategy used by many HM services—to demonstrate value by agreeing to comanage or admit patients for their primary-care (PCP) and specialist colleagues—had produced some unintended negative consequences. “Hospitalists,” he says, “are like the spackle of the hospital. Sometimes spackle is good; it hides flaws and imperfections. But at other times, people use spackle to fix major structural problems.”

Scope creep, mission creep, scut work: There are numerous ways to describe the phenomenon. In basic terms, hospitalists have been pressured to expand their scope of practice to manage all hospitalized patients. Hospitalist leaders differ about how much of an issue this really is, as managing hospitalized patients is the definition of hospitalist work. Burke T. Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn., and an SHM board member, points out that “one man’s scope creep is another man’s practice-builder.” John Nelson, MD, MHM, co-founder and past president of SHM and medical director of hospitalist services at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., says the expanding service trend is prevalent, but whether “it’s a problem depends on your point of view. The same stressful evolution occurs in every specialty. We are not unique in that regard.”

The trick, according to HM leaders, is to understand the dynamics that drive scope creep, then work proactively to address the problem.

Evolving Scope of Practice

It was not so long ago that hospitalist groups, seen by many in medicine as the new kids on the block, were perceived as a threat to their primary-care and specialist colleagues. To establish themselves, hospitalists began to demonstrate value by comanaging patients for their surgical colleagues, especially orthopedists. Some studies, notably those conducted by Mayo Clinic-based hospitalists, appeared to demonstrate that using hospitalists to help comanage orthopedic surgical patients results in improved outcomes.1,2

Dr. Siegal, however, points out that a closer parsing of those studies reveals that such outcomes as decreased time to surgery and length of stay (LOS) were better for patients with complex medical comorbidities, rather than all patients, which supports his argument that hospitalist comanagement makes most sense when applied to select groups of surgical patients.3

—Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, SHM board member, medical director of critical-care medicine, Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center, Milwaukee

As HM sprouted roots, clinicians across the country began to see an increase in requests for their services from primary-care physicians (PCPs) and subspecialists, as hospitalists freed them from rounding on patients and allowed them to concentrate on procedures for higher billings. Over the past 10 years, the expansion has been rapid, converging with multiple factors: increasing numbers of uninsured patients, an aging physician workforce, and diminishing reimbursement, to name a few.

Nailing down the extent to which comanagement has expanded HM’s scope of practice as a medical specialty is a slippery exercise. Some HM groups handle comanagement well; others do not. Dr. Kealey says that admitting and comanagement patterns are dependent on the culture of the institution. For example, in one of HealthPartners’ home hospitals, all internal-medicine subspecialties, including neurology, are admitted and managed by hospitalists with a subspecialty consult.

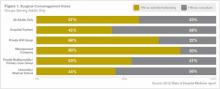

The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report survey revealed that 85% of respondent hospitalist groups provide surgical comanagement services (see Figure 1, below). That figure has not changed since SHM’s 2005-2006 survey, the last time the question was asked.

Another 20% of respondent hospitalist groups reported providing medical subspecialty comanagement, according to the 2012 report. Dr. Kealey, who is board liaison to SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, says plans are in the works to add specific questions to the survey to assess another big change in the comanagement arena: a shift from hospitalists acting as consultants with the specialist serving as attending physician to a model in which the hospitalist admits the patient and serves as attending, with the specialist/proceduralist in a consulting role.

So What’s the Problem?

Hospitalists have been both the utility player and the superstar, providing great value to their healthcare teams, says Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, a hospitalist practice-management consultant and CEO of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine. He believes hospitalist program expansions are typically a positive thing.

“Historically, most hospital medicine programs have embraced the call for assistance from both their colleagues and the C-suite,” says Dr. Simone, a Team Hospitalist member.

Dr. Siegal, in his HM07 presentation “Managing Comanagement: How to Play in the Sandbox without Having to Eat Mud Pies” and in journal articles, has cautioned against assuming that all hospitalized patients, irrespective of diagnosis or comorbidities, should be seen by a hospitalist.3 Such a directive can produce a host of unintended negative consequences. Most notably, it can:

- Confuse patients, families, and the care team about who is ultimately responsible for oversight of the patient’s care;

- Place hospitalists in the position of assuming responsibility for patients whose conditions are outside their scope of practice;

- Delay the initiation of appropriate, specialized care;

- Overwork an already stretched hospitalist team, which can lead to burnout; and

- Increase exposure to medical liability by placing hospitalists in situations where they are in over their heads, or by creating novel opportunities for miscommunication between hospitalists and surgeons or specialists.

Pressure Points

Scope creep’s root cause has multiple layers. It can be driven by overworked physicians; by local shortages in a particular specialty; by the bottom line, when procedure-focused physicians and surgeons want to divest themselves of day-to-day management of hospitalized patients; by lifestyle preferences; or by hospitalists’ success.

Jerome C. Siy, MD, SFHM, department head of hospital medicine for HealthPartners and recipient of the 2009 SHM Award for Clinical Excellence, believes the single most important factor behind the pressure to manage more hospitalized patients is the necessity to provide more thorough care when specialists or residents cannot.

“The hours of coverage are expanding in every specialty to a 24/7 model,” he says. “Since we hospitalists were in the hospital already, it became more routine for other services to ask us to get initial orders and the history and physical started, as a bridge to a better coverage model.”

Dr. Kealey says the “bridge” is a point of concern for many HM groups, especially when the pressure comes from hospital administrators attempting to attract specialists. Hospitalists have the right in such situations, says Dr. Siy, to feel undersupported or that they lack crucial knowledge or skill sets. Still, Dr. Kealey sees requests from other physician groups as a positive thing for hospitalists.

“We’re going to be managing more in the future,” he says, noting his HM group first drew up a comanagement agreement with orthopedic surgeons 17 years ago. “We want to go there thoughtfully and carefully. We shouldn’t put our foot down and say no to new opportunity.”

Rules of Engagement

Nearly every hospitalist leader agrees that the key to protecting against scope creep resides with thoughtful, proactive planning. Make sure, they say, that your group is ready to manage the patients you’re being asked to manage (see “Define and Protect Your Scope of Practice,” p. 35).

—Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, regional chief medical officer, Sound Physicians, Boston

Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, regional chief medical officer at Sound Physicians in the greater Boston area, agrees with Dr. Kealey in that he sees opportunity where others might perceive burden. For example, he notes, the advent of value-based purchasing initiatives, linking payment to quality, will create “huge opportunities for hospitalists.” More than 50% of the quality core measures in these initiatives are related to the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP).4

“Now, more than ever, hospitalists need to align with their partners in the hospital C-suite to help them be successful around those targets,” Dr. Radzienda says. However, he adds, “it behooves the HM teams to be very methodical and not rush this.”

Crafting clear rules of engagement must be handled properly and thoughtfully at the outset, Dr. Radzienda explains, and developing mutual trust and respect between the parties is the most essential step. Logistically, this can present problems.

“Getting surgeons and hospitalists together at a table is hard work,” he says. “But I can’t underscore that more: This requires a relationship. And it’s not something that is done via email exchange or memoranda through the respective practices’ business managers.”

It’s also critical to have nursing on board, says Julie Weegman, RN, MA, OCN, director of nursing and medical surgical services at HealthPartners’ Regions Hospital in St. Paul. “Communication is key in this kind of arrangement,” she says. “Nurses could potentially be put in a bad position if there are tensions between hospitalists and the specialty departments.”

That isn’t the case at Regions, though, where the comanagement agreement between orthopedics and HM has been clearly established, Weegman says. Questions about the surgical site, activity, and weight-bearing are referred to surgeons, while chronic disease management, blood pressure, glucose monitoring, etc., usually are handled by hospitalists.

Dr. Radzienda stresses that patients must remain at the center of the equation. “At three o’clock in the morning, with the post-op ortho patient who is having pain, nausea, or bleeding, it cannot be a multistep process to decide which doc is going to take that call and deliver on the patient’s needs,” he says.

Dr. Nelson, who co-founded SHM and serves as The Hospitalist’s practice-management columnist, cautions that service agreements are not a panacea. “This won’t totally solve your problems,” he says, “because every doctor is authorized to violate agreements if they see fit and if they can prove their patient is the exception to the rule.”

The bottom-line test for Dr. Siegal: Consider the patient’s best interests. Ask yourself, he advises, “if your mother came into the hospital with a head bleed, who would you want her to see first? Hospitalists are not interchangeable with neurosurgeons, and yet, unfortunately, we have started marketing ourselves as being adequate replacements for people who have spent far more time training in a specialty.

“As an intensivist, I’ve got a bit of experience with head bleeds,” he says. “But the neurosurgeon still knows more.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in central California.

References

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1): 28-38.

- Roy A, Heckman MG, Roy V. Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality-of-care-related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):28-31.

- Siegal EM. Just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should: A call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):398-402.

- The Joint Commission. Surgical Care Improvement Project. The Joint Commission website. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/surgical_care_improvement_project/. Accessed Sept. 30, 2012.

Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, vividly recalls the moment when he realized “scope creep” had become a problem. A hospitalist partner who was working a night shift admitted a young man who had been in a high-speed motor vehicle accident. The hospitalist did so because the general surgeon did not want to come into the hospital.

Dr. Siegal, currently the medical director of critical-care medicine at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, remembers looking at his partner and asking, “What the hell are you doing admitting a trauma patient? You’re an internist!”

Dr. Siegal’s partner responded, “I’m just trying to show value.”

“That was an ‘a-ha’ moment for me,” says Dr. Siegal, a member of SHM’s board of directors. It was at that point he began to understand that the expansion strategy used by many HM services—to demonstrate value by agreeing to comanage or admit patients for their primary-care (PCP) and specialist colleagues—had produced some unintended negative consequences. “Hospitalists,” he says, “are like the spackle of the hospital. Sometimes spackle is good; it hides flaws and imperfections. But at other times, people use spackle to fix major structural problems.”

Scope creep, mission creep, scut work: There are numerous ways to describe the phenomenon. In basic terms, hospitalists have been pressured to expand their scope of practice to manage all hospitalized patients. Hospitalist leaders differ about how much of an issue this really is, as managing hospitalized patients is the definition of hospitalist work. Burke T. Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn., and an SHM board member, points out that “one man’s scope creep is another man’s practice-builder.” John Nelson, MD, MHM, co-founder and past president of SHM and medical director of hospitalist services at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., says the expanding service trend is prevalent, but whether “it’s a problem depends on your point of view. The same stressful evolution occurs in every specialty. We are not unique in that regard.”

The trick, according to HM leaders, is to understand the dynamics that drive scope creep, then work proactively to address the problem.

Evolving Scope of Practice

It was not so long ago that hospitalist groups, seen by many in medicine as the new kids on the block, were perceived as a threat to their primary-care and specialist colleagues. To establish themselves, hospitalists began to demonstrate value by comanaging patients for their surgical colleagues, especially orthopedists. Some studies, notably those conducted by Mayo Clinic-based hospitalists, appeared to demonstrate that using hospitalists to help comanage orthopedic surgical patients results in improved outcomes.1,2

Dr. Siegal, however, points out that a closer parsing of those studies reveals that such outcomes as decreased time to surgery and length of stay (LOS) were better for patients with complex medical comorbidities, rather than all patients, which supports his argument that hospitalist comanagement makes most sense when applied to select groups of surgical patients.3

—Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, SHM board member, medical director of critical-care medicine, Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center, Milwaukee

As HM sprouted roots, clinicians across the country began to see an increase in requests for their services from primary-care physicians (PCPs) and subspecialists, as hospitalists freed them from rounding on patients and allowed them to concentrate on procedures for higher billings. Over the past 10 years, the expansion has been rapid, converging with multiple factors: increasing numbers of uninsured patients, an aging physician workforce, and diminishing reimbursement, to name a few.

Nailing down the extent to which comanagement has expanded HM’s scope of practice as a medical specialty is a slippery exercise. Some HM groups handle comanagement well; others do not. Dr. Kealey says that admitting and comanagement patterns are dependent on the culture of the institution. For example, in one of HealthPartners’ home hospitals, all internal-medicine subspecialties, including neurology, are admitted and managed by hospitalists with a subspecialty consult.

The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report survey revealed that 85% of respondent hospitalist groups provide surgical comanagement services (see Figure 1, below). That figure has not changed since SHM’s 2005-2006 survey, the last time the question was asked.

Another 20% of respondent hospitalist groups reported providing medical subspecialty comanagement, according to the 2012 report. Dr. Kealey, who is board liaison to SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, says plans are in the works to add specific questions to the survey to assess another big change in the comanagement arena: a shift from hospitalists acting as consultants with the specialist serving as attending physician to a model in which the hospitalist admits the patient and serves as attending, with the specialist/proceduralist in a consulting role.

So What’s the Problem?

Hospitalists have been both the utility player and the superstar, providing great value to their healthcare teams, says Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, a hospitalist practice-management consultant and CEO of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine. He believes hospitalist program expansions are typically a positive thing.

“Historically, most hospital medicine programs have embraced the call for assistance from both their colleagues and the C-suite,” says Dr. Simone, a Team Hospitalist member.

Dr. Siegal, in his HM07 presentation “Managing Comanagement: How to Play in the Sandbox without Having to Eat Mud Pies” and in journal articles, has cautioned against assuming that all hospitalized patients, irrespective of diagnosis or comorbidities, should be seen by a hospitalist.3 Such a directive can produce a host of unintended negative consequences. Most notably, it can:

- Confuse patients, families, and the care team about who is ultimately responsible for oversight of the patient’s care;

- Place hospitalists in the position of assuming responsibility for patients whose conditions are outside their scope of practice;

- Delay the initiation of appropriate, specialized care;

- Overwork an already stretched hospitalist team, which can lead to burnout; and

- Increase exposure to medical liability by placing hospitalists in situations where they are in over their heads, or by creating novel opportunities for miscommunication between hospitalists and surgeons or specialists.

Pressure Points

Scope creep’s root cause has multiple layers. It can be driven by overworked physicians; by local shortages in a particular specialty; by the bottom line, when procedure-focused physicians and surgeons want to divest themselves of day-to-day management of hospitalized patients; by lifestyle preferences; or by hospitalists’ success.

Jerome C. Siy, MD, SFHM, department head of hospital medicine for HealthPartners and recipient of the 2009 SHM Award for Clinical Excellence, believes the single most important factor behind the pressure to manage more hospitalized patients is the necessity to provide more thorough care when specialists or residents cannot.

“The hours of coverage are expanding in every specialty to a 24/7 model,” he says. “Since we hospitalists were in the hospital already, it became more routine for other services to ask us to get initial orders and the history and physical started, as a bridge to a better coverage model.”

Dr. Kealey says the “bridge” is a point of concern for many HM groups, especially when the pressure comes from hospital administrators attempting to attract specialists. Hospitalists have the right in such situations, says Dr. Siy, to feel undersupported or that they lack crucial knowledge or skill sets. Still, Dr. Kealey sees requests from other physician groups as a positive thing for hospitalists.

“We’re going to be managing more in the future,” he says, noting his HM group first drew up a comanagement agreement with orthopedic surgeons 17 years ago. “We want to go there thoughtfully and carefully. We shouldn’t put our foot down and say no to new opportunity.”

Rules of Engagement

Nearly every hospitalist leader agrees that the key to protecting against scope creep resides with thoughtful, proactive planning. Make sure, they say, that your group is ready to manage the patients you’re being asked to manage (see “Define and Protect Your Scope of Practice,” p. 35).

—Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, regional chief medical officer, Sound Physicians, Boston

Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, regional chief medical officer at Sound Physicians in the greater Boston area, agrees with Dr. Kealey in that he sees opportunity where others might perceive burden. For example, he notes, the advent of value-based purchasing initiatives, linking payment to quality, will create “huge opportunities for hospitalists.” More than 50% of the quality core measures in these initiatives are related to the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP).4

“Now, more than ever, hospitalists need to align with their partners in the hospital C-suite to help them be successful around those targets,” Dr. Radzienda says. However, he adds, “it behooves the HM teams to be very methodical and not rush this.”

Crafting clear rules of engagement must be handled properly and thoughtfully at the outset, Dr. Radzienda explains, and developing mutual trust and respect between the parties is the most essential step. Logistically, this can present problems.

“Getting surgeons and hospitalists together at a table is hard work,” he says. “But I can’t underscore that more: This requires a relationship. And it’s not something that is done via email exchange or memoranda through the respective practices’ business managers.”

It’s also critical to have nursing on board, says Julie Weegman, RN, MA, OCN, director of nursing and medical surgical services at HealthPartners’ Regions Hospital in St. Paul. “Communication is key in this kind of arrangement,” she says. “Nurses could potentially be put in a bad position if there are tensions between hospitalists and the specialty departments.”

That isn’t the case at Regions, though, where the comanagement agreement between orthopedics and HM has been clearly established, Weegman says. Questions about the surgical site, activity, and weight-bearing are referred to surgeons, while chronic disease management, blood pressure, glucose monitoring, etc., usually are handled by hospitalists.

Dr. Radzienda stresses that patients must remain at the center of the equation. “At three o’clock in the morning, with the post-op ortho patient who is having pain, nausea, or bleeding, it cannot be a multistep process to decide which doc is going to take that call and deliver on the patient’s needs,” he says.

Dr. Nelson, who co-founded SHM and serves as The Hospitalist’s practice-management columnist, cautions that service agreements are not a panacea. “This won’t totally solve your problems,” he says, “because every doctor is authorized to violate agreements if they see fit and if they can prove their patient is the exception to the rule.”

The bottom-line test for Dr. Siegal: Consider the patient’s best interests. Ask yourself, he advises, “if your mother came into the hospital with a head bleed, who would you want her to see first? Hospitalists are not interchangeable with neurosurgeons, and yet, unfortunately, we have started marketing ourselves as being adequate replacements for people who have spent far more time training in a specialty.

“As an intensivist, I’ve got a bit of experience with head bleeds,” he says. “But the neurosurgeon still knows more.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in central California.

References

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1): 28-38.

- Roy A, Heckman MG, Roy V. Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality-of-care-related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):28-31.

- Siegal EM. Just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should: A call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):398-402.

- The Joint Commission. Surgical Care Improvement Project. The Joint Commission website. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/surgical_care_improvement_project/. Accessed Sept. 30, 2012.

Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, vividly recalls the moment when he realized “scope creep” had become a problem. A hospitalist partner who was working a night shift admitted a young man who had been in a high-speed motor vehicle accident. The hospitalist did so because the general surgeon did not want to come into the hospital.

Dr. Siegal, currently the medical director of critical-care medicine at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, remembers looking at his partner and asking, “What the hell are you doing admitting a trauma patient? You’re an internist!”

Dr. Siegal’s partner responded, “I’m just trying to show value.”

“That was an ‘a-ha’ moment for me,” says Dr. Siegal, a member of SHM’s board of directors. It was at that point he began to understand that the expansion strategy used by many HM services—to demonstrate value by agreeing to comanage or admit patients for their primary-care (PCP) and specialist colleagues—had produced some unintended negative consequences. “Hospitalists,” he says, “are like the spackle of the hospital. Sometimes spackle is good; it hides flaws and imperfections. But at other times, people use spackle to fix major structural problems.”

Scope creep, mission creep, scut work: There are numerous ways to describe the phenomenon. In basic terms, hospitalists have been pressured to expand their scope of practice to manage all hospitalized patients. Hospitalist leaders differ about how much of an issue this really is, as managing hospitalized patients is the definition of hospitalist work. Burke T. Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn., and an SHM board member, points out that “one man’s scope creep is another man’s practice-builder.” John Nelson, MD, MHM, co-founder and past president of SHM and medical director of hospitalist services at Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, Wash., says the expanding service trend is prevalent, but whether “it’s a problem depends on your point of view. The same stressful evolution occurs in every specialty. We are not unique in that regard.”

The trick, according to HM leaders, is to understand the dynamics that drive scope creep, then work proactively to address the problem.

Evolving Scope of Practice

It was not so long ago that hospitalist groups, seen by many in medicine as the new kids on the block, were perceived as a threat to their primary-care and specialist colleagues. To establish themselves, hospitalists began to demonstrate value by comanaging patients for their surgical colleagues, especially orthopedists. Some studies, notably those conducted by Mayo Clinic-based hospitalists, appeared to demonstrate that using hospitalists to help comanage orthopedic surgical patients results in improved outcomes.1,2

Dr. Siegal, however, points out that a closer parsing of those studies reveals that such outcomes as decreased time to surgery and length of stay (LOS) were better for patients with complex medical comorbidities, rather than all patients, which supports his argument that hospitalist comanagement makes most sense when applied to select groups of surgical patients.3

—Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, SHM board member, medical director of critical-care medicine, Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center, Milwaukee

As HM sprouted roots, clinicians across the country began to see an increase in requests for their services from primary-care physicians (PCPs) and subspecialists, as hospitalists freed them from rounding on patients and allowed them to concentrate on procedures for higher billings. Over the past 10 years, the expansion has been rapid, converging with multiple factors: increasing numbers of uninsured patients, an aging physician workforce, and diminishing reimbursement, to name a few.

Nailing down the extent to which comanagement has expanded HM’s scope of practice as a medical specialty is a slippery exercise. Some HM groups handle comanagement well; others do not. Dr. Kealey says that admitting and comanagement patterns are dependent on the culture of the institution. For example, in one of HealthPartners’ home hospitals, all internal-medicine subspecialties, including neurology, are admitted and managed by hospitalists with a subspecialty consult.

The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report survey revealed that 85% of respondent hospitalist groups provide surgical comanagement services (see Figure 1, below). That figure has not changed since SHM’s 2005-2006 survey, the last time the question was asked.

Another 20% of respondent hospitalist groups reported providing medical subspecialty comanagement, according to the 2012 report. Dr. Kealey, who is board liaison to SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, says plans are in the works to add specific questions to the survey to assess another big change in the comanagement arena: a shift from hospitalists acting as consultants with the specialist serving as attending physician to a model in which the hospitalist admits the patient and serves as attending, with the specialist/proceduralist in a consulting role.

So What’s the Problem?

Hospitalists have been both the utility player and the superstar, providing great value to their healthcare teams, says Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, a hospitalist practice-management consultant and CEO of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine. He believes hospitalist program expansions are typically a positive thing.

“Historically, most hospital medicine programs have embraced the call for assistance from both their colleagues and the C-suite,” says Dr. Simone, a Team Hospitalist member.

Dr. Siegal, in his HM07 presentation “Managing Comanagement: How to Play in the Sandbox without Having to Eat Mud Pies” and in journal articles, has cautioned against assuming that all hospitalized patients, irrespective of diagnosis or comorbidities, should be seen by a hospitalist.3 Such a directive can produce a host of unintended negative consequences. Most notably, it can:

- Confuse patients, families, and the care team about who is ultimately responsible for oversight of the patient’s care;

- Place hospitalists in the position of assuming responsibility for patients whose conditions are outside their scope of practice;

- Delay the initiation of appropriate, specialized care;

- Overwork an already stretched hospitalist team, which can lead to burnout; and

- Increase exposure to medical liability by placing hospitalists in situations where they are in over their heads, or by creating novel opportunities for miscommunication between hospitalists and surgeons or specialists.

Pressure Points

Scope creep’s root cause has multiple layers. It can be driven by overworked physicians; by local shortages in a particular specialty; by the bottom line, when procedure-focused physicians and surgeons want to divest themselves of day-to-day management of hospitalized patients; by lifestyle preferences; or by hospitalists’ success.

Jerome C. Siy, MD, SFHM, department head of hospital medicine for HealthPartners and recipient of the 2009 SHM Award for Clinical Excellence, believes the single most important factor behind the pressure to manage more hospitalized patients is the necessity to provide more thorough care when specialists or residents cannot.

“The hours of coverage are expanding in every specialty to a 24/7 model,” he says. “Since we hospitalists were in the hospital already, it became more routine for other services to ask us to get initial orders and the history and physical started, as a bridge to a better coverage model.”

Dr. Kealey says the “bridge” is a point of concern for many HM groups, especially when the pressure comes from hospital administrators attempting to attract specialists. Hospitalists have the right in such situations, says Dr. Siy, to feel undersupported or that they lack crucial knowledge or skill sets. Still, Dr. Kealey sees requests from other physician groups as a positive thing for hospitalists.

“We’re going to be managing more in the future,” he says, noting his HM group first drew up a comanagement agreement with orthopedic surgeons 17 years ago. “We want to go there thoughtfully and carefully. We shouldn’t put our foot down and say no to new opportunity.”

Rules of Engagement

Nearly every hospitalist leader agrees that the key to protecting against scope creep resides with thoughtful, proactive planning. Make sure, they say, that your group is ready to manage the patients you’re being asked to manage (see “Define and Protect Your Scope of Practice,” p. 35).

—Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, regional chief medical officer, Sound Physicians, Boston

Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, regional chief medical officer at Sound Physicians in the greater Boston area, agrees with Dr. Kealey in that he sees opportunity where others might perceive burden. For example, he notes, the advent of value-based purchasing initiatives, linking payment to quality, will create “huge opportunities for hospitalists.” More than 50% of the quality core measures in these initiatives are related to the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP).4

“Now, more than ever, hospitalists need to align with their partners in the hospital C-suite to help them be successful around those targets,” Dr. Radzienda says. However, he adds, “it behooves the HM teams to be very methodical and not rush this.”

Crafting clear rules of engagement must be handled properly and thoughtfully at the outset, Dr. Radzienda explains, and developing mutual trust and respect between the parties is the most essential step. Logistically, this can present problems.

“Getting surgeons and hospitalists together at a table is hard work,” he says. “But I can’t underscore that more: This requires a relationship. And it’s not something that is done via email exchange or memoranda through the respective practices’ business managers.”

It’s also critical to have nursing on board, says Julie Weegman, RN, MA, OCN, director of nursing and medical surgical services at HealthPartners’ Regions Hospital in St. Paul. “Communication is key in this kind of arrangement,” she says. “Nurses could potentially be put in a bad position if there are tensions between hospitalists and the specialty departments.”

That isn’t the case at Regions, though, where the comanagement agreement between orthopedics and HM has been clearly established, Weegman says. Questions about the surgical site, activity, and weight-bearing are referred to surgeons, while chronic disease management, blood pressure, glucose monitoring, etc., usually are handled by hospitalists.

Dr. Radzienda stresses that patients must remain at the center of the equation. “At three o’clock in the morning, with the post-op ortho patient who is having pain, nausea, or bleeding, it cannot be a multistep process to decide which doc is going to take that call and deliver on the patient’s needs,” he says.

Dr. Nelson, who co-founded SHM and serves as The Hospitalist’s practice-management columnist, cautions that service agreements are not a panacea. “This won’t totally solve your problems,” he says, “because every doctor is authorized to violate agreements if they see fit and if they can prove their patient is the exception to the rule.”

The bottom-line test for Dr. Siegal: Consider the patient’s best interests. Ask yourself, he advises, “if your mother came into the hospital with a head bleed, who would you want her to see first? Hospitalists are not interchangeable with neurosurgeons, and yet, unfortunately, we have started marketing ourselves as being adequate replacements for people who have spent far more time training in a specialty.

“As an intensivist, I’ve got a bit of experience with head bleeds,” he says. “But the neurosurgeon still knows more.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in central California.

References

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1): 28-38.

- Roy A, Heckman MG, Roy V. Associations between the hospitalist model of care and quality-of-care-related outcomes in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):28-31.

- Siegal EM. Just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should: A call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):398-402.

- The Joint Commission. Surgical Care Improvement Project. The Joint Commission website. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/surgical_care_improvement_project/. Accessed Sept. 30, 2012.