User login

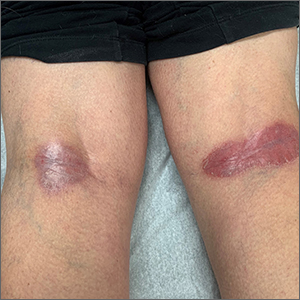

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

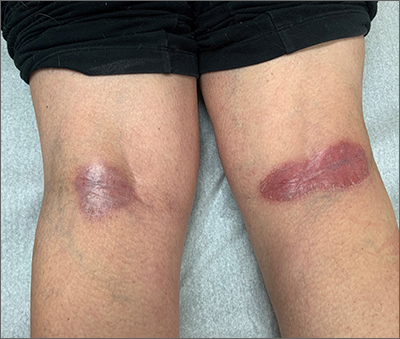

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

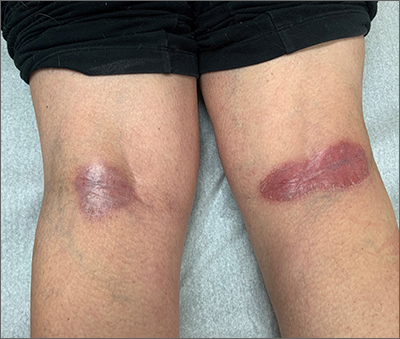

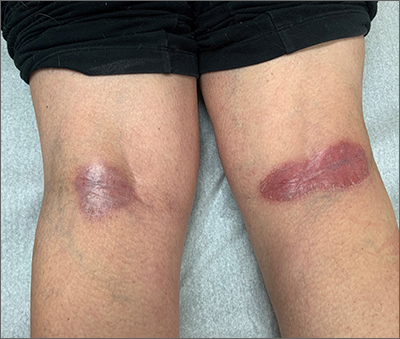

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733