User login

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis leading to hospital admission.[1] Approximately 12% of hospitalized patients who present with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites have spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP); half of these patients do not present with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, or vomiting.[2] Guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend paracentesis for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites and also recommend long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis for survivors of an SBP episode.[3] Despite evidence that in‐hospital mortality is reduced in those patients who receive paracentesis in a timely manner,[4, 5] only 40% to 60% of eligible patients receive paracentesis.[4, 6, 7] We aimed to describe clinical predictors of paracentesis and use of antibiotics following an episode of SBP in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults admitted to a single tertiary care center between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009.7 We included patients with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision discharge code consistent with decompensated cirrhosis who met clinical criteria for decompensated cirrhosis (see

RESULTS

We identified 193 admissions for 103 patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites (Table 1). Of these, 41% (80/193) received diagnostic paracentesis. Mean/standard deviation for age was 53.6/12.4 years; 71% of patients were male and 63% were English speaking. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (33%), psychiatric diagnosis (29%), substance abuse (18%), and renal failure (17%). Excluding SBP, 31% of patients had another documented infection. Gastroenterology was consulted in 50% of the admissions. Fever was present in 27% of patients, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count (ie, WBC >11 k/mm3) was present in 27% of patients, International Normalized Ratio (INR) was elevated (>1.1) in 92% of patients, and 16% of patients had a platelet count of 50,000/mm3. Patients who received paracentesis were less likely to have a fever on presentation (19% vs 32%, P=0.06), low (ie, 50,000/mm3) platelet count (11% vs 19%, P=0.14), or concurrent gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (6% vs 16%, P=0.05). In a multiple logistic regression model including characteristics associated at P0.2 with paracentesis, fever, low platelet count, and concurrent GI bleeding were associated with decreased odds of receiving paracentesis (Appendix 1).

| Overall, N=193, Mean/SD or N (%)* | Paracentesis (), n=113, Mean/SD or N (%) | Paracentesis (+), n=80, Mean/SD or N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 53.6/12.4 | 54.1/13.4 | 53.2/11.7 | 1.00 (0.981.03) |

| Sex (male) | 137 (71.0%) | 78 (69.0%) | 59 (73.8%) | 1.26 (0.672.39) |

| English speaking | 122 (63.2%) | 69 (61.1%) | 53 (66.3%) | 1.25 (0.692.28) |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 120 (62.2%) | 74 (65.5%) | 46 (57.5%) | 0.71 (0.401.29) |

| Hepatitis C | 94 (48.7%) | 57 (50.4%) | 37 (46.3%) | 0.85 (0.481.50) |

| Hepatitis B | 16 (8.3%) | 7 (6.2%) | 9 (11.3%) | 1.92 (0.685.39) |

| NASH | 8 (4.2%) | 4 (3.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 1.43 (0.355.91) |

| Cryptogenic | 11 (5.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 5 (6.3%) | 1.19 (0.354.04) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Substance abuse | 34 (17.6%) | 22 (19.5%) | 12 (15.0%) | 0.73 (0.341.58) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 55 (28.5%) | 38 (33.6%) | 17 (21.3%) | 0.53 (0.271.03) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (32.6%) | 37 (32.7%) | 26 (32.5%) | 0.99 (0.541.82) |

| Renal failure | 33 (17.1%) | 20 (17.7%) | 13 (16.3%) | 0.90 (0.421.94) |

| GI bleed | 23 (11.9%) | 18 (15.9%) | 5 (6.3%) | 0.35 (0.120.99) |

| Admission MELD | 17.3/7.3 | 17.5/7.3 | 17.0/7.3 | 0.99 (0.951.03) |

| Creatinine, median/IQR | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.8 | 1.02 (0.821.27) |

| Gastroenterology consult | 97 (50.3%) | 46 (40.7%) | 51 (63.8%) | 2.56 (1.424.63) |

| Infection, UTI, pneumonia, other | 60 (31.1%) | 38 (33.6%) | 22 (27.5%) | 0.75 (0.401.40) |

| Temperature 100.4F | 49 (26.8%) | 34 (32.4%) | 15 (19.2%) | 0.50 (0.251.00) |

| WBC >11 k/mm3 | 50 (27.3%) | 28 (26.7%) | 22 (28.2%) | 1.08 (0.562.08) |

| WBC 4 k/mm3 | 43 (23.5%) | 23 (21.9%) | 20 (25.6%) | 1.23 (0.622.44) |

| INR >1.1 | 149 (92.0%) | 83 (93.3%) | 66 (90.4%) | 0.68 (0.222.13) |

| Highest temperature, F | 98.9/1.1 | 99.1/1.3 | 98.8/0.8 | 0.82 (0.621.09) |

| Highest HR | 98.2/20.4 | 97.4/22.4 | 99.2/17.4 | 1.00 (0.991.02) |

| Highest RR | 24.5/13.7 | 25.2/16.8 | 23.5/7.8 | 0.99 (0.961.02) |

| Lowest SBP | 101.0/20.0 | 99.4/20.3 | 102.2/19.7 | 0.99 (0.981.01) |

| Lowest MAP | 73.0/12.2 | 73.2/13.3 | 72.7/10.6 | 1.00 (0.971.02) |

| Lowest O2Sat | 92.6/13.6 | 91.0/17.7 | 94.9/2.8 | 1.04 (0.991.10) |

| Highest PT | 15.8/3.8 | 15.9/3.7 | 15.7/3.9 | 0.98 (0.901.08) |

| Platelets 50 k/mm3 | 30 (15.9%) | 21 (19.3%) | 9 (11.3%) | 0.53 (0.231.23) |

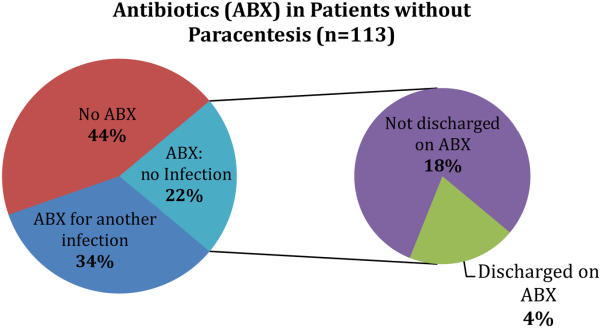

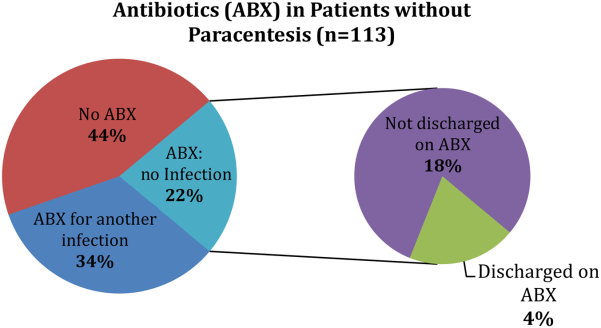

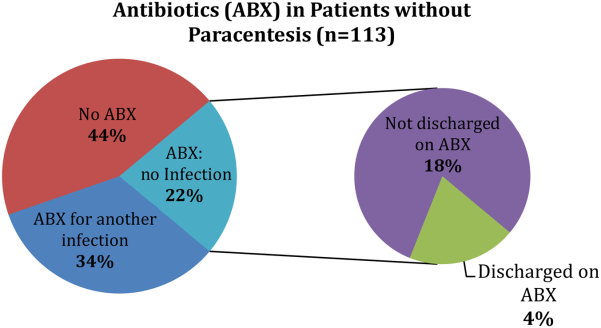

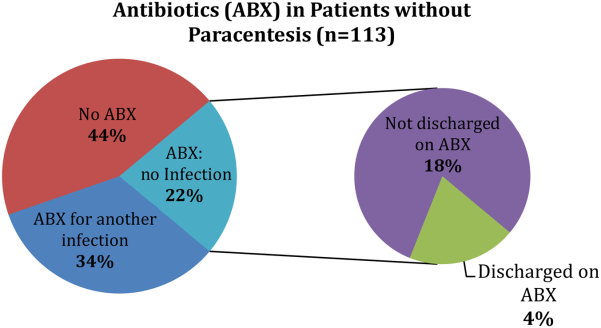

Of the patients who received paracentesis (n=80), 14% were diagnosed with SBP. Of these, 55% received prophylaxis on discharge. Among the patients who did not receive paracentesis (n=113), 38 (34%) received antibiotics for another documented infection (eg, pneumonia), and 25 patients (22%) received antibiotics with no other documented infection or evidence of variceal bleeding. Of these 25 patients who were presumed to be empirically treated for SBP (Figure 1), only 20% were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics on discharge.

CONCLUSION

We found that many patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites did not receive paracentesis when hospitalized, which is similar to previously published data.[4, 6, 7] Clinical evidence of infection, such as fever or elevated WBC count, did not increase the odds of receiving paracentesis. Many patients treated for SBP were not discharged on prophylaxis.

This study is limited by its small single‐center design. We could only use data from 1 year (2009), because study data collection was part of a quality‐improvement project that took place for that year only. We did not adjust for the number of red blood cells in the ascitic fluid samples. We were also unable to determine the timing of gastroenterology consultation (whether it was done prior to paracentesis), admission venue (floor vs intensive care), or patient history of SBP.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications. First, the decision to perform paracentesis was not associated with symptoms of infection, although some clinical factors (eg, low platelets or GI bleeding) were associated with reduced odds of receiving paracentesis. Second, a majority of patients treated for SBP did not receive prophylactic antibiotics at discharge. These findings suggest a clear opportunity to increase awareness and acceptance of AASLD guidelines among hospital medicine practitioners. Quality‐improvement efforts should focus on the education of providers, and future research should identify barriers to paracentesis at both the practitioner and system levels (eg, availability of interventional radiology). Checklists or decision support within electronic order entry systems may also help reduce the low rates of paracentesis seen in our and prior studies.[4, 6, 7]

Disclosures: Dr. Lagu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling had full access to all of the data in the study. They take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling conceived of the study. Dr. Ghaoui acquired the data. Ms. Friderici carried out the statistical analyses. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, Brooling, Lindenauer, and Ms. Friderici analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , ; Spanish Collaborative Study Group On Therapeutic Management In Liver Disease. Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58(6):435–440.

- , , , et al. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33(1):41–48.

- , AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651–1653.

- , , , . Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):496–503.e1.

- , , , et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1436–1442.

- , , , et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):70–77.

- , , , , , . Measurement of the quality of care of patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34(2):204–210.

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis leading to hospital admission.[1] Approximately 12% of hospitalized patients who present with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites have spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP); half of these patients do not present with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, or vomiting.[2] Guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend paracentesis for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites and also recommend long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis for survivors of an SBP episode.[3] Despite evidence that in‐hospital mortality is reduced in those patients who receive paracentesis in a timely manner,[4, 5] only 40% to 60% of eligible patients receive paracentesis.[4, 6, 7] We aimed to describe clinical predictors of paracentesis and use of antibiotics following an episode of SBP in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults admitted to a single tertiary care center between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009.7 We included patients with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision discharge code consistent with decompensated cirrhosis who met clinical criteria for decompensated cirrhosis (see

RESULTS

We identified 193 admissions for 103 patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites (Table 1). Of these, 41% (80/193) received diagnostic paracentesis. Mean/standard deviation for age was 53.6/12.4 years; 71% of patients were male and 63% were English speaking. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (33%), psychiatric diagnosis (29%), substance abuse (18%), and renal failure (17%). Excluding SBP, 31% of patients had another documented infection. Gastroenterology was consulted in 50% of the admissions. Fever was present in 27% of patients, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count (ie, WBC >11 k/mm3) was present in 27% of patients, International Normalized Ratio (INR) was elevated (>1.1) in 92% of patients, and 16% of patients had a platelet count of 50,000/mm3. Patients who received paracentesis were less likely to have a fever on presentation (19% vs 32%, P=0.06), low (ie, 50,000/mm3) platelet count (11% vs 19%, P=0.14), or concurrent gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (6% vs 16%, P=0.05). In a multiple logistic regression model including characteristics associated at P0.2 with paracentesis, fever, low platelet count, and concurrent GI bleeding were associated with decreased odds of receiving paracentesis (Appendix 1).

| Overall, N=193, Mean/SD or N (%)* | Paracentesis (), n=113, Mean/SD or N (%) | Paracentesis (+), n=80, Mean/SD or N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 53.6/12.4 | 54.1/13.4 | 53.2/11.7 | 1.00 (0.981.03) |

| Sex (male) | 137 (71.0%) | 78 (69.0%) | 59 (73.8%) | 1.26 (0.672.39) |

| English speaking | 122 (63.2%) | 69 (61.1%) | 53 (66.3%) | 1.25 (0.692.28) |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 120 (62.2%) | 74 (65.5%) | 46 (57.5%) | 0.71 (0.401.29) |

| Hepatitis C | 94 (48.7%) | 57 (50.4%) | 37 (46.3%) | 0.85 (0.481.50) |

| Hepatitis B | 16 (8.3%) | 7 (6.2%) | 9 (11.3%) | 1.92 (0.685.39) |

| NASH | 8 (4.2%) | 4 (3.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 1.43 (0.355.91) |

| Cryptogenic | 11 (5.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 5 (6.3%) | 1.19 (0.354.04) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Substance abuse | 34 (17.6%) | 22 (19.5%) | 12 (15.0%) | 0.73 (0.341.58) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 55 (28.5%) | 38 (33.6%) | 17 (21.3%) | 0.53 (0.271.03) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (32.6%) | 37 (32.7%) | 26 (32.5%) | 0.99 (0.541.82) |

| Renal failure | 33 (17.1%) | 20 (17.7%) | 13 (16.3%) | 0.90 (0.421.94) |

| GI bleed | 23 (11.9%) | 18 (15.9%) | 5 (6.3%) | 0.35 (0.120.99) |

| Admission MELD | 17.3/7.3 | 17.5/7.3 | 17.0/7.3 | 0.99 (0.951.03) |

| Creatinine, median/IQR | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.8 | 1.02 (0.821.27) |

| Gastroenterology consult | 97 (50.3%) | 46 (40.7%) | 51 (63.8%) | 2.56 (1.424.63) |

| Infection, UTI, pneumonia, other | 60 (31.1%) | 38 (33.6%) | 22 (27.5%) | 0.75 (0.401.40) |

| Temperature 100.4F | 49 (26.8%) | 34 (32.4%) | 15 (19.2%) | 0.50 (0.251.00) |

| WBC >11 k/mm3 | 50 (27.3%) | 28 (26.7%) | 22 (28.2%) | 1.08 (0.562.08) |

| WBC 4 k/mm3 | 43 (23.5%) | 23 (21.9%) | 20 (25.6%) | 1.23 (0.622.44) |

| INR >1.1 | 149 (92.0%) | 83 (93.3%) | 66 (90.4%) | 0.68 (0.222.13) |

| Highest temperature, F | 98.9/1.1 | 99.1/1.3 | 98.8/0.8 | 0.82 (0.621.09) |

| Highest HR | 98.2/20.4 | 97.4/22.4 | 99.2/17.4 | 1.00 (0.991.02) |

| Highest RR | 24.5/13.7 | 25.2/16.8 | 23.5/7.8 | 0.99 (0.961.02) |

| Lowest SBP | 101.0/20.0 | 99.4/20.3 | 102.2/19.7 | 0.99 (0.981.01) |

| Lowest MAP | 73.0/12.2 | 73.2/13.3 | 72.7/10.6 | 1.00 (0.971.02) |

| Lowest O2Sat | 92.6/13.6 | 91.0/17.7 | 94.9/2.8 | 1.04 (0.991.10) |

| Highest PT | 15.8/3.8 | 15.9/3.7 | 15.7/3.9 | 0.98 (0.901.08) |

| Platelets 50 k/mm3 | 30 (15.9%) | 21 (19.3%) | 9 (11.3%) | 0.53 (0.231.23) |

Of the patients who received paracentesis (n=80), 14% were diagnosed with SBP. Of these, 55% received prophylaxis on discharge. Among the patients who did not receive paracentesis (n=113), 38 (34%) received antibiotics for another documented infection (eg, pneumonia), and 25 patients (22%) received antibiotics with no other documented infection or evidence of variceal bleeding. Of these 25 patients who were presumed to be empirically treated for SBP (Figure 1), only 20% were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics on discharge.

CONCLUSION

We found that many patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites did not receive paracentesis when hospitalized, which is similar to previously published data.[4, 6, 7] Clinical evidence of infection, such as fever or elevated WBC count, did not increase the odds of receiving paracentesis. Many patients treated for SBP were not discharged on prophylaxis.

This study is limited by its small single‐center design. We could only use data from 1 year (2009), because study data collection was part of a quality‐improvement project that took place for that year only. We did not adjust for the number of red blood cells in the ascitic fluid samples. We were also unable to determine the timing of gastroenterology consultation (whether it was done prior to paracentesis), admission venue (floor vs intensive care), or patient history of SBP.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications. First, the decision to perform paracentesis was not associated with symptoms of infection, although some clinical factors (eg, low platelets or GI bleeding) were associated with reduced odds of receiving paracentesis. Second, a majority of patients treated for SBP did not receive prophylactic antibiotics at discharge. These findings suggest a clear opportunity to increase awareness and acceptance of AASLD guidelines among hospital medicine practitioners. Quality‐improvement efforts should focus on the education of providers, and future research should identify barriers to paracentesis at both the practitioner and system levels (eg, availability of interventional radiology). Checklists or decision support within electronic order entry systems may also help reduce the low rates of paracentesis seen in our and prior studies.[4, 6, 7]

Disclosures: Dr. Lagu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling had full access to all of the data in the study. They take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling conceived of the study. Dr. Ghaoui acquired the data. Ms. Friderici carried out the statistical analyses. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, Brooling, Lindenauer, and Ms. Friderici analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis leading to hospital admission.[1] Approximately 12% of hospitalized patients who present with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites have spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP); half of these patients do not present with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, or vomiting.[2] Guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend paracentesis for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites and also recommend long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis for survivors of an SBP episode.[3] Despite evidence that in‐hospital mortality is reduced in those patients who receive paracentesis in a timely manner,[4, 5] only 40% to 60% of eligible patients receive paracentesis.[4, 6, 7] We aimed to describe clinical predictors of paracentesis and use of antibiotics following an episode of SBP in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults admitted to a single tertiary care center between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009.7 We included patients with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision discharge code consistent with decompensated cirrhosis who met clinical criteria for decompensated cirrhosis (see

RESULTS

We identified 193 admissions for 103 patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites (Table 1). Of these, 41% (80/193) received diagnostic paracentesis. Mean/standard deviation for age was 53.6/12.4 years; 71% of patients were male and 63% were English speaking. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (33%), psychiatric diagnosis (29%), substance abuse (18%), and renal failure (17%). Excluding SBP, 31% of patients had another documented infection. Gastroenterology was consulted in 50% of the admissions. Fever was present in 27% of patients, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count (ie, WBC >11 k/mm3) was present in 27% of patients, International Normalized Ratio (INR) was elevated (>1.1) in 92% of patients, and 16% of patients had a platelet count of 50,000/mm3. Patients who received paracentesis were less likely to have a fever on presentation (19% vs 32%, P=0.06), low (ie, 50,000/mm3) platelet count (11% vs 19%, P=0.14), or concurrent gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (6% vs 16%, P=0.05). In a multiple logistic regression model including characteristics associated at P0.2 with paracentesis, fever, low platelet count, and concurrent GI bleeding were associated with decreased odds of receiving paracentesis (Appendix 1).

| Overall, N=193, Mean/SD or N (%)* | Paracentesis (), n=113, Mean/SD or N (%) | Paracentesis (+), n=80, Mean/SD or N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 53.6/12.4 | 54.1/13.4 | 53.2/11.7 | 1.00 (0.981.03) |

| Sex (male) | 137 (71.0%) | 78 (69.0%) | 59 (73.8%) | 1.26 (0.672.39) |

| English speaking | 122 (63.2%) | 69 (61.1%) | 53 (66.3%) | 1.25 (0.692.28) |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 120 (62.2%) | 74 (65.5%) | 46 (57.5%) | 0.71 (0.401.29) |

| Hepatitis C | 94 (48.7%) | 57 (50.4%) | 37 (46.3%) | 0.85 (0.481.50) |

| Hepatitis B | 16 (8.3%) | 7 (6.2%) | 9 (11.3%) | 1.92 (0.685.39) |

| NASH | 8 (4.2%) | 4 (3.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 1.43 (0.355.91) |

| Cryptogenic | 11 (5.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 5 (6.3%) | 1.19 (0.354.04) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Substance abuse | 34 (17.6%) | 22 (19.5%) | 12 (15.0%) | 0.73 (0.341.58) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 55 (28.5%) | 38 (33.6%) | 17 (21.3%) | 0.53 (0.271.03) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (32.6%) | 37 (32.7%) | 26 (32.5%) | 0.99 (0.541.82) |

| Renal failure | 33 (17.1%) | 20 (17.7%) | 13 (16.3%) | 0.90 (0.421.94) |

| GI bleed | 23 (11.9%) | 18 (15.9%) | 5 (6.3%) | 0.35 (0.120.99) |

| Admission MELD | 17.3/7.3 | 17.5/7.3 | 17.0/7.3 | 0.99 (0.951.03) |

| Creatinine, median/IQR | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.8 | 1.02 (0.821.27) |

| Gastroenterology consult | 97 (50.3%) | 46 (40.7%) | 51 (63.8%) | 2.56 (1.424.63) |

| Infection, UTI, pneumonia, other | 60 (31.1%) | 38 (33.6%) | 22 (27.5%) | 0.75 (0.401.40) |

| Temperature 100.4F | 49 (26.8%) | 34 (32.4%) | 15 (19.2%) | 0.50 (0.251.00) |

| WBC >11 k/mm3 | 50 (27.3%) | 28 (26.7%) | 22 (28.2%) | 1.08 (0.562.08) |

| WBC 4 k/mm3 | 43 (23.5%) | 23 (21.9%) | 20 (25.6%) | 1.23 (0.622.44) |

| INR >1.1 | 149 (92.0%) | 83 (93.3%) | 66 (90.4%) | 0.68 (0.222.13) |

| Highest temperature, F | 98.9/1.1 | 99.1/1.3 | 98.8/0.8 | 0.82 (0.621.09) |

| Highest HR | 98.2/20.4 | 97.4/22.4 | 99.2/17.4 | 1.00 (0.991.02) |

| Highest RR | 24.5/13.7 | 25.2/16.8 | 23.5/7.8 | 0.99 (0.961.02) |

| Lowest SBP | 101.0/20.0 | 99.4/20.3 | 102.2/19.7 | 0.99 (0.981.01) |

| Lowest MAP | 73.0/12.2 | 73.2/13.3 | 72.7/10.6 | 1.00 (0.971.02) |

| Lowest O2Sat | 92.6/13.6 | 91.0/17.7 | 94.9/2.8 | 1.04 (0.991.10) |

| Highest PT | 15.8/3.8 | 15.9/3.7 | 15.7/3.9 | 0.98 (0.901.08) |

| Platelets 50 k/mm3 | 30 (15.9%) | 21 (19.3%) | 9 (11.3%) | 0.53 (0.231.23) |

Of the patients who received paracentesis (n=80), 14% were diagnosed with SBP. Of these, 55% received prophylaxis on discharge. Among the patients who did not receive paracentesis (n=113), 38 (34%) received antibiotics for another documented infection (eg, pneumonia), and 25 patients (22%) received antibiotics with no other documented infection or evidence of variceal bleeding. Of these 25 patients who were presumed to be empirically treated for SBP (Figure 1), only 20% were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics on discharge.

CONCLUSION

We found that many patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites did not receive paracentesis when hospitalized, which is similar to previously published data.[4, 6, 7] Clinical evidence of infection, such as fever or elevated WBC count, did not increase the odds of receiving paracentesis. Many patients treated for SBP were not discharged on prophylaxis.

This study is limited by its small single‐center design. We could only use data from 1 year (2009), because study data collection was part of a quality‐improvement project that took place for that year only. We did not adjust for the number of red blood cells in the ascitic fluid samples. We were also unable to determine the timing of gastroenterology consultation (whether it was done prior to paracentesis), admission venue (floor vs intensive care), or patient history of SBP.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications. First, the decision to perform paracentesis was not associated with symptoms of infection, although some clinical factors (eg, low platelets or GI bleeding) were associated with reduced odds of receiving paracentesis. Second, a majority of patients treated for SBP did not receive prophylactic antibiotics at discharge. These findings suggest a clear opportunity to increase awareness and acceptance of AASLD guidelines among hospital medicine practitioners. Quality‐improvement efforts should focus on the education of providers, and future research should identify barriers to paracentesis at both the practitioner and system levels (eg, availability of interventional radiology). Checklists or decision support within electronic order entry systems may also help reduce the low rates of paracentesis seen in our and prior studies.[4, 6, 7]

Disclosures: Dr. Lagu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling had full access to all of the data in the study. They take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling conceived of the study. Dr. Ghaoui acquired the data. Ms. Friderici carried out the statistical analyses. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, Brooling, Lindenauer, and Ms. Friderici analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , ; Spanish Collaborative Study Group On Therapeutic Management In Liver Disease. Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58(6):435–440.

- , , , et al. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33(1):41–48.

- , AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651–1653.

- , , , . Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):496–503.e1.

- , , , et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1436–1442.

- , , , et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):70–77.

- , , , , , . Measurement of the quality of care of patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34(2):204–210.

- , , , , ; Spanish Collaborative Study Group On Therapeutic Management In Liver Disease. Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58(6):435–440.

- , , , et al. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33(1):41–48.

- , AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651–1653.

- , , , . Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):496–503.e1.

- , , , et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1436–1442.

- , , , et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):70–77.

- , , , , , . Measurement of the quality of care of patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34(2):204–210.