User login

In the decade or so since the World Health Organization (WHO) first characterized the terms osteoporosis and osteopenia, basing them on bone-density measurements from dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), we have come to know the definitions well, thanks to attention in the lay and medical press (TABLE 1).1

What is the goal behind the heightened public awareness? To reduce the number of osteoporotic fractures.

Do the WHO definitions further this goal? Not really.

Rather than an isolated numerical value, a more useful and descriptive definition of osteoporosis is the following: a skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and disruption of bone tissue architecture that reduces the mechanical strength of the skeleton and increases the risk of fragility fractures.

In many cases, this definition would encompass women now diagnosed as having osteopenia. Unfortunately, although risk factors for osteoporosis have been described and well promulgated (TABLE 2), the almost exclusive focus of diagnosis has been and continues to be DXA scanning and the WHO definitions, with their reliance on the term osteopenia to convey heightened risk short of full-blown osteoporosis.

This article explains why that way of assessing a woman’s risk of fracture is not the most informative. In fact, the term osteopenia has very little clinical relevance. Some women in the osteopenic range have a high risk of fracture in the short term, whereas others have a great deal of bone health. The hope is that this term will be retired in the near future and replaced with tools that enable us to calculate the absolute fracture risk in 5 to 10 years.

TABLE 1

World Health Organization’s diagnostic categories for bone mineral density

| BONE MINERAL DENSITY MEASUREMENT | DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| Within 1 standard deviation of young adult mean | Normal |

| 1 to 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean | Osteopenia |

| More than 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean | Osteoporosis |

| More than 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean, with fragility fractures | Severe osteoporosis |

| Source: WHO.1 | |

TABLE 2

13 major osteoporosis risk factors in postmenopausal women

|

Only 1 piece of the puzzle

Bone mineral density (BMD) measures bone mass, which is simply 1 component of bone strength. BMD does not assess bone microarchitecture, although it can facilitate a diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis using the WHO definitions.

We use BMD to monitor risk of fracture, much as blood pressure predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease. Many patients with high blood pressure never have a heart attack or stroke, and many patients with normal blood pressure do—but overall, rising blood pressure and rising risk of cardiovascular disease go together.

We use BMD to monitor response to treatment, but it is accurate only if the concept of least-specific change (LSC) is taken into account: LSC=2.77×the precision error of the machine. Thus, in a good center, BMD measurement of the spine will be ±3%, and measurement of the hip will be ±5%.

Bone loss is a continuum, not a T score

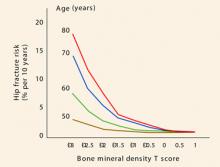

Another limitation of the term osteopenia: There is a lot of distance under the curve from –1 to –2.49 standard deviations. Thus, when it comes to risk assessment, it is important to remember that loss of bone mass is a continuum. And because the risk of fracture is directly related to bone mass, fracture risk is a continuum, too. For every standard deviation of bone mass lost, the relative risk of fracture doubles, but absolute fracture risk is highly age-dependent (FIGURE 1).

In younger women, the relative risk of fracture is quite low, and it remains low even when doubled.

However, as careful inspection of FIGURE 1 reveals, the absolute fracture risk of a 50-year-old with a T score of –3 (a score most clinicians would be very concerned about) is exactly the same as the absolute fracture risk of an 80-year-old woman with a T score of –1 (a score many clinicians might consider excellent for a woman that age).

Thus, the T score is only part of the story.

Another example: A 38-year-old woman with a long history of poor calcium ingestion and several years of hypomenorrhea in her 20s has a T score of –2. This woman does not have the same fracture risk as a 63-year-old woman who also has a T score of –2, but who had a T score of 0 when she entered menopause at age 49. These 2 women have the same bone mass, but very different levels of bone quality and fracture risk.

So which women should have their bone mass tested?

Various organizations have issued guidelines for measuring BMD in women to assess risk of fracture (TABLE 3).

FIGURE 1 Risk of fracture increases with advancing age and continuous loss of bone

Adapted from Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Dawson A, De Laet C, Jonsson B. Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:989–995.TABLE 3

3 sets of guidelines on who needs a bone mineral density test

| ORGANIZATION | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| National Osteoporosis Foundation2 |

|

| US Preventive Services Task Force3 |

|

| International Society for Clinical Densitometry4 |

|

| NOTE: Per guidelines of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry, women discontinuing estrogen should be considered for bone-density testing according to the indications listed above. | |

When to intervene?

It should be said that it is never too early to intervene when it comes to important lifestyle issues. Adequate calcium and vitamin D are essential throughout life for all women. Encouraging patients to quit smoking is crucial, as is fall prevention, especially for frail women and those with poor eyesight. It is beneficial for women to maintain flexibility, agility, mobility, and strength; these are important components of bone health and total health, and should be taught early in life.

Teriparatide is a bone builder…

This agent is the first parathyroid hormone analog that is anabolic and can build new bone. All the older, familiar agents (estrogen, bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators) are antiresorptive. That is, they act by retarding the resorptive part of the dynamic lifelong process whereby bone is constantly laid down and taken away.

…not a magic bullet

When I first heard of anabolic compounds such as teriparatide several years ago, I naively thought it might be possible to modify our approach to bone health. Instead of treating patients to prevent osteoporosis, why not simply wait until patients developed the disease and then treat them with anabolic bone-building agents?

The problem with such reasoning is this: Although the risk of fracture is higher in women with osteoporosis, the number of fractures is greater in postmenopausal women with osteopenia because there are so many more women with osteopenia than with osteoporosis. In fact, the Surgeon General’s report on the state of bone health in the United States estimated that 34 million women have osteopenia and 10 million women have osteoporosis.5

Thus, it becomes obvious that we cannot simply wait until women have developed osteoporosis to treat them if we are going to prevent the majority of fragility fractures.

3 studies exposed risk of osteopenic fracture

The MORE trial

The Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial6 involved 7,705 women less than 80 years of age in a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter, double-blind study of postmenopausal osteoporosis. One of the groups studied had T scores as low as –2.5 and no previous fractures. The other group had 1 or more vertebral fractures at baseline. Women were randomized to raloxifene or placebo for 3 years. Partway through the trial the relevant T-score database was corrected,6 which had the effect of recategorizing many women originally enrolled with “osteoporosis” as “osteopenic.”

In the placebo group of 1,152 osteopenic women with no preexisting vertebral fractures, 42 new vertebral fractures occurred (rate: 3.6%). In addition, of 298 women with osteoporosis, 19 new vertebral fractures occurred (rate: 6.4%). Thus, the fracture rate in osteoporotic women is greater, but the prevalence in osteopenic women is much higher. In this case, the ratio of osteopenic to osteoporotic women was 3.9:1. This ratio is not dissimilar to that of 3.4:1 cited in the Surgeon General’s report.5

The Rotterdam study

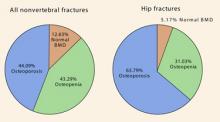

This trial7 followed 4,878 women older than 55 years by obtaining BMD measurements of the femoral neck through DXA scanning for an average of 6.8 years. More than one third of the hip fractures occurred in women without osteoporosis (FIGURE 2). In fact, 5% of the hip fractures occurred in women with normal BMD!

In terms of all nonvertebral fractures, more than half occurred in women without osteoporosis, and 12% occurred in women with normal BMD.

FIGURE 2 The majority of nonvertebral fractures and a significant minority of hip fractures occurred in women not yet osteoporotic—ROTTERDAM TRIAL

Source: Schuit SC, et al.7

The NORA trial

The National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment8 (NORA) also tells us a lot about osteopenic women. This trial was a longitudinal family-practice–based study involving slightly more than 200,000 women. It was a 3-year study with 1 year of follow-up. All women self-reported baseline characteristics and received a peripheral measurement of bone density, either by single-energy x-ray absorptiometry, peripheral DXA, or ultrasound.

The authors applied WHO guidelines for BMD measurement, recognizing that their values were peripheral and might therefore understate BMD values based on central DXA.

Ninety percent of the study population was white. The average age was 64.5 years (range 50–104 years), and 11% had previous fractures. (This fracture rate may underrepresent the actual number of previous fractures because the data were self-reported.) Twenty-two percent had a maternal history of osteoporosis.

These patients may have been healthier than the general population because, in order to be part of the study, they had to have a personal physician. Seven percent of the patients had osteoporosis and 40% had osteopenia, based on the peripheral BMD measurements.

The risk of fracture differed significantly by race. The various relative risks are shown in TABLE 4.

Of the postmenopausal women who sustained new fractures within 1 year of study entry, 82% had peripheral BMD measurements in the osteopenic range.

TABLE 4

Relative risk by race NORA trial

| RACE | RELATIVE RISK (RANGE) |

|---|---|

| Caucasian (reference group) | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) |

| Hispanic | 1.31 (1.19–1.44) |

| Asian | 1.56 (1.32–1.85) |

| Source: Siris E, et al.8 | |

So whom do we treat?

As has been observed, osteopenic women clearly constitute the majority of women with fractures, not to mention a sizeable number of women in general. As noted, the T-score range of –1 to –2.49 is wide. It is not feasible to treat the entire osteopenic population. Thus, there is a need to stratify risk.

Miller et al9 attempted to solve this problem by identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. They analyzed the records of more than 57,000 white women from the NORA trial with peripheral T scores that were osteopenic, and entered 32 risk factors for fracture into a regression-tree analysis. They found 1,130 new fractures that occurred within 1 year.

Signs of imminent fracture

The most important determinants of short-term fracture risk (1 year) were:

- previous fracture regardless of T score (4.1% risk),

- T score of less than –1.8 (2.2% risk),

- poor health status (2.2% risk), and

- poor mobility (1.9% risk).9

These 4 risk factors do not differ substantially from the current National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines (TABLE 5), which recommend treating all women with previous fractures, T scores worse than –2, or T scores worse than –1.5 with additional risk factors.

TABLE 5

Protocol to prevent osteoporotic fractures National Osteoporosis Foundation

| Calcium intake 1,200 mg/day |

| Vitamin D 400–800 IU/day if risk is high |

| Regular weight-bearing, muscle-strengthening exercise |

| No smoking |

| Moderate alcohol consumption |

| Treatment of all vertebral and hip fractures |

Consider prophylactic treatment if:

|

Looking ahead

The WHO scientific group met in 2004 in Brussels, with representatives from leading organizations, including the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, the International Osteoporosis Foundation, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation, to name a few. The hope is that we will soon have tools to calculate a 5- or 10-year absolute risk of fracture using multiple parameters such as age, body mass index, smoking, ever use of steroids, previous fracture, family history, and BMD. With such a tool, all we would need to do is establish the level of risk at which pharmacotherapy should be initiated.

Disclosure

Dr. Goldstein reports that he serves on the gynecology advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and TAP Pharmaceuticals.

1. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1-129.

2. Physician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2003.

3. Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:526-528.

4. Position statement: executive summary. The Writing Group for the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD). Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2004;4:7-12

5. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.

6. Kanis JA, Johnell O, Black DM, et al. Effect of raloxifene on the risk of new vertebral fracture in post-menopausal women with osteopenia or osteoporosis: a reanalysis of the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation trial. Bone. 2003;3:293-300

7. Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202

8. Siris E, Miller P, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA. 2001;286:2815-2822

9. Miller PD, Barlas S, Brenneman SK, et al. An approach to identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1113-1120

In the decade or so since the World Health Organization (WHO) first characterized the terms osteoporosis and osteopenia, basing them on bone-density measurements from dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), we have come to know the definitions well, thanks to attention in the lay and medical press (TABLE 1).1

What is the goal behind the heightened public awareness? To reduce the number of osteoporotic fractures.

Do the WHO definitions further this goal? Not really.

Rather than an isolated numerical value, a more useful and descriptive definition of osteoporosis is the following: a skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and disruption of bone tissue architecture that reduces the mechanical strength of the skeleton and increases the risk of fragility fractures.

In many cases, this definition would encompass women now diagnosed as having osteopenia. Unfortunately, although risk factors for osteoporosis have been described and well promulgated (TABLE 2), the almost exclusive focus of diagnosis has been and continues to be DXA scanning and the WHO definitions, with their reliance on the term osteopenia to convey heightened risk short of full-blown osteoporosis.

This article explains why that way of assessing a woman’s risk of fracture is not the most informative. In fact, the term osteopenia has very little clinical relevance. Some women in the osteopenic range have a high risk of fracture in the short term, whereas others have a great deal of bone health. The hope is that this term will be retired in the near future and replaced with tools that enable us to calculate the absolute fracture risk in 5 to 10 years.

TABLE 1

World Health Organization’s diagnostic categories for bone mineral density

| BONE MINERAL DENSITY MEASUREMENT | DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| Within 1 standard deviation of young adult mean | Normal |

| 1 to 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean | Osteopenia |

| More than 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean | Osteoporosis |

| More than 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean, with fragility fractures | Severe osteoporosis |

| Source: WHO.1 | |

TABLE 2

13 major osteoporosis risk factors in postmenopausal women

|

Only 1 piece of the puzzle

Bone mineral density (BMD) measures bone mass, which is simply 1 component of bone strength. BMD does not assess bone microarchitecture, although it can facilitate a diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis using the WHO definitions.

We use BMD to monitor risk of fracture, much as blood pressure predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease. Many patients with high blood pressure never have a heart attack or stroke, and many patients with normal blood pressure do—but overall, rising blood pressure and rising risk of cardiovascular disease go together.

We use BMD to monitor response to treatment, but it is accurate only if the concept of least-specific change (LSC) is taken into account: LSC=2.77×the precision error of the machine. Thus, in a good center, BMD measurement of the spine will be ±3%, and measurement of the hip will be ±5%.

Bone loss is a continuum, not a T score

Another limitation of the term osteopenia: There is a lot of distance under the curve from –1 to –2.49 standard deviations. Thus, when it comes to risk assessment, it is important to remember that loss of bone mass is a continuum. And because the risk of fracture is directly related to bone mass, fracture risk is a continuum, too. For every standard deviation of bone mass lost, the relative risk of fracture doubles, but absolute fracture risk is highly age-dependent (FIGURE 1).

In younger women, the relative risk of fracture is quite low, and it remains low even when doubled.

However, as careful inspection of FIGURE 1 reveals, the absolute fracture risk of a 50-year-old with a T score of –3 (a score most clinicians would be very concerned about) is exactly the same as the absolute fracture risk of an 80-year-old woman with a T score of –1 (a score many clinicians might consider excellent for a woman that age).

Thus, the T score is only part of the story.

Another example: A 38-year-old woman with a long history of poor calcium ingestion and several years of hypomenorrhea in her 20s has a T score of –2. This woman does not have the same fracture risk as a 63-year-old woman who also has a T score of –2, but who had a T score of 0 when she entered menopause at age 49. These 2 women have the same bone mass, but very different levels of bone quality and fracture risk.

So which women should have their bone mass tested?

Various organizations have issued guidelines for measuring BMD in women to assess risk of fracture (TABLE 3).

FIGURE 1 Risk of fracture increases with advancing age and continuous loss of bone

Adapted from Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Dawson A, De Laet C, Jonsson B. Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:989–995.TABLE 3

3 sets of guidelines on who needs a bone mineral density test

| ORGANIZATION | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| National Osteoporosis Foundation2 |

|

| US Preventive Services Task Force3 |

|

| International Society for Clinical Densitometry4 |

|

| NOTE: Per guidelines of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry, women discontinuing estrogen should be considered for bone-density testing according to the indications listed above. | |

When to intervene?

It should be said that it is never too early to intervene when it comes to important lifestyle issues. Adequate calcium and vitamin D are essential throughout life for all women. Encouraging patients to quit smoking is crucial, as is fall prevention, especially for frail women and those with poor eyesight. It is beneficial for women to maintain flexibility, agility, mobility, and strength; these are important components of bone health and total health, and should be taught early in life.

Teriparatide is a bone builder…

This agent is the first parathyroid hormone analog that is anabolic and can build new bone. All the older, familiar agents (estrogen, bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators) are antiresorptive. That is, they act by retarding the resorptive part of the dynamic lifelong process whereby bone is constantly laid down and taken away.

…not a magic bullet

When I first heard of anabolic compounds such as teriparatide several years ago, I naively thought it might be possible to modify our approach to bone health. Instead of treating patients to prevent osteoporosis, why not simply wait until patients developed the disease and then treat them with anabolic bone-building agents?

The problem with such reasoning is this: Although the risk of fracture is higher in women with osteoporosis, the number of fractures is greater in postmenopausal women with osteopenia because there are so many more women with osteopenia than with osteoporosis. In fact, the Surgeon General’s report on the state of bone health in the United States estimated that 34 million women have osteopenia and 10 million women have osteoporosis.5

Thus, it becomes obvious that we cannot simply wait until women have developed osteoporosis to treat them if we are going to prevent the majority of fragility fractures.

3 studies exposed risk of osteopenic fracture

The MORE trial

The Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial6 involved 7,705 women less than 80 years of age in a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter, double-blind study of postmenopausal osteoporosis. One of the groups studied had T scores as low as –2.5 and no previous fractures. The other group had 1 or more vertebral fractures at baseline. Women were randomized to raloxifene or placebo for 3 years. Partway through the trial the relevant T-score database was corrected,6 which had the effect of recategorizing many women originally enrolled with “osteoporosis” as “osteopenic.”

In the placebo group of 1,152 osteopenic women with no preexisting vertebral fractures, 42 new vertebral fractures occurred (rate: 3.6%). In addition, of 298 women with osteoporosis, 19 new vertebral fractures occurred (rate: 6.4%). Thus, the fracture rate in osteoporotic women is greater, but the prevalence in osteopenic women is much higher. In this case, the ratio of osteopenic to osteoporotic women was 3.9:1. This ratio is not dissimilar to that of 3.4:1 cited in the Surgeon General’s report.5

The Rotterdam study

This trial7 followed 4,878 women older than 55 years by obtaining BMD measurements of the femoral neck through DXA scanning for an average of 6.8 years. More than one third of the hip fractures occurred in women without osteoporosis (FIGURE 2). In fact, 5% of the hip fractures occurred in women with normal BMD!

In terms of all nonvertebral fractures, more than half occurred in women without osteoporosis, and 12% occurred in women with normal BMD.

FIGURE 2 The majority of nonvertebral fractures and a significant minority of hip fractures occurred in women not yet osteoporotic—ROTTERDAM TRIAL

Source: Schuit SC, et al.7

The NORA trial

The National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment8 (NORA) also tells us a lot about osteopenic women. This trial was a longitudinal family-practice–based study involving slightly more than 200,000 women. It was a 3-year study with 1 year of follow-up. All women self-reported baseline characteristics and received a peripheral measurement of bone density, either by single-energy x-ray absorptiometry, peripheral DXA, or ultrasound.

The authors applied WHO guidelines for BMD measurement, recognizing that their values were peripheral and might therefore understate BMD values based on central DXA.

Ninety percent of the study population was white. The average age was 64.5 years (range 50–104 years), and 11% had previous fractures. (This fracture rate may underrepresent the actual number of previous fractures because the data were self-reported.) Twenty-two percent had a maternal history of osteoporosis.

These patients may have been healthier than the general population because, in order to be part of the study, they had to have a personal physician. Seven percent of the patients had osteoporosis and 40% had osteopenia, based on the peripheral BMD measurements.

The risk of fracture differed significantly by race. The various relative risks are shown in TABLE 4.

Of the postmenopausal women who sustained new fractures within 1 year of study entry, 82% had peripheral BMD measurements in the osteopenic range.

TABLE 4

Relative risk by race NORA trial

| RACE | RELATIVE RISK (RANGE) |

|---|---|

| Caucasian (reference group) | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) |

| Hispanic | 1.31 (1.19–1.44) |

| Asian | 1.56 (1.32–1.85) |

| Source: Siris E, et al.8 | |

So whom do we treat?

As has been observed, osteopenic women clearly constitute the majority of women with fractures, not to mention a sizeable number of women in general. As noted, the T-score range of –1 to –2.49 is wide. It is not feasible to treat the entire osteopenic population. Thus, there is a need to stratify risk.

Miller et al9 attempted to solve this problem by identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. They analyzed the records of more than 57,000 white women from the NORA trial with peripheral T scores that were osteopenic, and entered 32 risk factors for fracture into a regression-tree analysis. They found 1,130 new fractures that occurred within 1 year.

Signs of imminent fracture

The most important determinants of short-term fracture risk (1 year) were:

- previous fracture regardless of T score (4.1% risk),

- T score of less than –1.8 (2.2% risk),

- poor health status (2.2% risk), and

- poor mobility (1.9% risk).9

These 4 risk factors do not differ substantially from the current National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines (TABLE 5), which recommend treating all women with previous fractures, T scores worse than –2, or T scores worse than –1.5 with additional risk factors.

TABLE 5

Protocol to prevent osteoporotic fractures National Osteoporosis Foundation

| Calcium intake 1,200 mg/day |

| Vitamin D 400–800 IU/day if risk is high |

| Regular weight-bearing, muscle-strengthening exercise |

| No smoking |

| Moderate alcohol consumption |

| Treatment of all vertebral and hip fractures |

Consider prophylactic treatment if:

|

Looking ahead

The WHO scientific group met in 2004 in Brussels, with representatives from leading organizations, including the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, the International Osteoporosis Foundation, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation, to name a few. The hope is that we will soon have tools to calculate a 5- or 10-year absolute risk of fracture using multiple parameters such as age, body mass index, smoking, ever use of steroids, previous fracture, family history, and BMD. With such a tool, all we would need to do is establish the level of risk at which pharmacotherapy should be initiated.

Disclosure

Dr. Goldstein reports that he serves on the gynecology advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and TAP Pharmaceuticals.

In the decade or so since the World Health Organization (WHO) first characterized the terms osteoporosis and osteopenia, basing them on bone-density measurements from dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), we have come to know the definitions well, thanks to attention in the lay and medical press (TABLE 1).1

What is the goal behind the heightened public awareness? To reduce the number of osteoporotic fractures.

Do the WHO definitions further this goal? Not really.

Rather than an isolated numerical value, a more useful and descriptive definition of osteoporosis is the following: a skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and disruption of bone tissue architecture that reduces the mechanical strength of the skeleton and increases the risk of fragility fractures.

In many cases, this definition would encompass women now diagnosed as having osteopenia. Unfortunately, although risk factors for osteoporosis have been described and well promulgated (TABLE 2), the almost exclusive focus of diagnosis has been and continues to be DXA scanning and the WHO definitions, with their reliance on the term osteopenia to convey heightened risk short of full-blown osteoporosis.

This article explains why that way of assessing a woman’s risk of fracture is not the most informative. In fact, the term osteopenia has very little clinical relevance. Some women in the osteopenic range have a high risk of fracture in the short term, whereas others have a great deal of bone health. The hope is that this term will be retired in the near future and replaced with tools that enable us to calculate the absolute fracture risk in 5 to 10 years.

TABLE 1

World Health Organization’s diagnostic categories for bone mineral density

| BONE MINERAL DENSITY MEASUREMENT | DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|

| Within 1 standard deviation of young adult mean | Normal |

| 1 to 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean | Osteopenia |

| More than 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean | Osteoporosis |

| More than 2.5 standard deviations below young adult mean, with fragility fractures | Severe osteoporosis |

| Source: WHO.1 | |

TABLE 2

13 major osteoporosis risk factors in postmenopausal women

|

Only 1 piece of the puzzle

Bone mineral density (BMD) measures bone mass, which is simply 1 component of bone strength. BMD does not assess bone microarchitecture, although it can facilitate a diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis using the WHO definitions.

We use BMD to monitor risk of fracture, much as blood pressure predicts the risk of cardiovascular disease. Many patients with high blood pressure never have a heart attack or stroke, and many patients with normal blood pressure do—but overall, rising blood pressure and rising risk of cardiovascular disease go together.

We use BMD to monitor response to treatment, but it is accurate only if the concept of least-specific change (LSC) is taken into account: LSC=2.77×the precision error of the machine. Thus, in a good center, BMD measurement of the spine will be ±3%, and measurement of the hip will be ±5%.

Bone loss is a continuum, not a T score

Another limitation of the term osteopenia: There is a lot of distance under the curve from –1 to –2.49 standard deviations. Thus, when it comes to risk assessment, it is important to remember that loss of bone mass is a continuum. And because the risk of fracture is directly related to bone mass, fracture risk is a continuum, too. For every standard deviation of bone mass lost, the relative risk of fracture doubles, but absolute fracture risk is highly age-dependent (FIGURE 1).

In younger women, the relative risk of fracture is quite low, and it remains low even when doubled.

However, as careful inspection of FIGURE 1 reveals, the absolute fracture risk of a 50-year-old with a T score of –3 (a score most clinicians would be very concerned about) is exactly the same as the absolute fracture risk of an 80-year-old woman with a T score of –1 (a score many clinicians might consider excellent for a woman that age).

Thus, the T score is only part of the story.

Another example: A 38-year-old woman with a long history of poor calcium ingestion and several years of hypomenorrhea in her 20s has a T score of –2. This woman does not have the same fracture risk as a 63-year-old woman who also has a T score of –2, but who had a T score of 0 when she entered menopause at age 49. These 2 women have the same bone mass, but very different levels of bone quality and fracture risk.

So which women should have their bone mass tested?

Various organizations have issued guidelines for measuring BMD in women to assess risk of fracture (TABLE 3).

FIGURE 1 Risk of fracture increases with advancing age and continuous loss of bone

Adapted from Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Dawson A, De Laet C, Jonsson B. Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:989–995.TABLE 3

3 sets of guidelines on who needs a bone mineral density test

| ORGANIZATION | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| National Osteoporosis Foundation2 |

|

| US Preventive Services Task Force3 |

|

| International Society for Clinical Densitometry4 |

|

| NOTE: Per guidelines of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry, women discontinuing estrogen should be considered for bone-density testing according to the indications listed above. | |

When to intervene?

It should be said that it is never too early to intervene when it comes to important lifestyle issues. Adequate calcium and vitamin D are essential throughout life for all women. Encouraging patients to quit smoking is crucial, as is fall prevention, especially for frail women and those with poor eyesight. It is beneficial for women to maintain flexibility, agility, mobility, and strength; these are important components of bone health and total health, and should be taught early in life.

Teriparatide is a bone builder…

This agent is the first parathyroid hormone analog that is anabolic and can build new bone. All the older, familiar agents (estrogen, bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators) are antiresorptive. That is, they act by retarding the resorptive part of the dynamic lifelong process whereby bone is constantly laid down and taken away.

…not a magic bullet

When I first heard of anabolic compounds such as teriparatide several years ago, I naively thought it might be possible to modify our approach to bone health. Instead of treating patients to prevent osteoporosis, why not simply wait until patients developed the disease and then treat them with anabolic bone-building agents?

The problem with such reasoning is this: Although the risk of fracture is higher in women with osteoporosis, the number of fractures is greater in postmenopausal women with osteopenia because there are so many more women with osteopenia than with osteoporosis. In fact, the Surgeon General’s report on the state of bone health in the United States estimated that 34 million women have osteopenia and 10 million women have osteoporosis.5

Thus, it becomes obvious that we cannot simply wait until women have developed osteoporosis to treat them if we are going to prevent the majority of fragility fractures.

3 studies exposed risk of osteopenic fracture

The MORE trial

The Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial6 involved 7,705 women less than 80 years of age in a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter, double-blind study of postmenopausal osteoporosis. One of the groups studied had T scores as low as –2.5 and no previous fractures. The other group had 1 or more vertebral fractures at baseline. Women were randomized to raloxifene or placebo for 3 years. Partway through the trial the relevant T-score database was corrected,6 which had the effect of recategorizing many women originally enrolled with “osteoporosis” as “osteopenic.”

In the placebo group of 1,152 osteopenic women with no preexisting vertebral fractures, 42 new vertebral fractures occurred (rate: 3.6%). In addition, of 298 women with osteoporosis, 19 new vertebral fractures occurred (rate: 6.4%). Thus, the fracture rate in osteoporotic women is greater, but the prevalence in osteopenic women is much higher. In this case, the ratio of osteopenic to osteoporotic women was 3.9:1. This ratio is not dissimilar to that of 3.4:1 cited in the Surgeon General’s report.5

The Rotterdam study

This trial7 followed 4,878 women older than 55 years by obtaining BMD measurements of the femoral neck through DXA scanning for an average of 6.8 years. More than one third of the hip fractures occurred in women without osteoporosis (FIGURE 2). In fact, 5% of the hip fractures occurred in women with normal BMD!

In terms of all nonvertebral fractures, more than half occurred in women without osteoporosis, and 12% occurred in women with normal BMD.

FIGURE 2 The majority of nonvertebral fractures and a significant minority of hip fractures occurred in women not yet osteoporotic—ROTTERDAM TRIAL

Source: Schuit SC, et al.7

The NORA trial

The National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment8 (NORA) also tells us a lot about osteopenic women. This trial was a longitudinal family-practice–based study involving slightly more than 200,000 women. It was a 3-year study with 1 year of follow-up. All women self-reported baseline characteristics and received a peripheral measurement of bone density, either by single-energy x-ray absorptiometry, peripheral DXA, or ultrasound.

The authors applied WHO guidelines for BMD measurement, recognizing that their values were peripheral and might therefore understate BMD values based on central DXA.

Ninety percent of the study population was white. The average age was 64.5 years (range 50–104 years), and 11% had previous fractures. (This fracture rate may underrepresent the actual number of previous fractures because the data were self-reported.) Twenty-two percent had a maternal history of osteoporosis.

These patients may have been healthier than the general population because, in order to be part of the study, they had to have a personal physician. Seven percent of the patients had osteoporosis and 40% had osteopenia, based on the peripheral BMD measurements.

The risk of fracture differed significantly by race. The various relative risks are shown in TABLE 4.

Of the postmenopausal women who sustained new fractures within 1 year of study entry, 82% had peripheral BMD measurements in the osteopenic range.

TABLE 4

Relative risk by race NORA trial

| RACE | RELATIVE RISK (RANGE) |

|---|---|

| Caucasian (reference group) | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.55 (0.48–0.62) |

| Hispanic | 1.31 (1.19–1.44) |

| Asian | 1.56 (1.32–1.85) |

| Source: Siris E, et al.8 | |

So whom do we treat?

As has been observed, osteopenic women clearly constitute the majority of women with fractures, not to mention a sizeable number of women in general. As noted, the T-score range of –1 to –2.49 is wide. It is not feasible to treat the entire osteopenic population. Thus, there is a need to stratify risk.

Miller et al9 attempted to solve this problem by identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. They analyzed the records of more than 57,000 white women from the NORA trial with peripheral T scores that were osteopenic, and entered 32 risk factors for fracture into a regression-tree analysis. They found 1,130 new fractures that occurred within 1 year.

Signs of imminent fracture

The most important determinants of short-term fracture risk (1 year) were:

- previous fracture regardless of T score (4.1% risk),

- T score of less than –1.8 (2.2% risk),

- poor health status (2.2% risk), and

- poor mobility (1.9% risk).9

These 4 risk factors do not differ substantially from the current National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines (TABLE 5), which recommend treating all women with previous fractures, T scores worse than –2, or T scores worse than –1.5 with additional risk factors.

TABLE 5

Protocol to prevent osteoporotic fractures National Osteoporosis Foundation

| Calcium intake 1,200 mg/day |

| Vitamin D 400–800 IU/day if risk is high |

| Regular weight-bearing, muscle-strengthening exercise |

| No smoking |

| Moderate alcohol consumption |

| Treatment of all vertebral and hip fractures |

Consider prophylactic treatment if:

|

Looking ahead

The WHO scientific group met in 2004 in Brussels, with representatives from leading organizations, including the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, the International Osteoporosis Foundation, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation, to name a few. The hope is that we will soon have tools to calculate a 5- or 10-year absolute risk of fracture using multiple parameters such as age, body mass index, smoking, ever use of steroids, previous fracture, family history, and BMD. With such a tool, all we would need to do is establish the level of risk at which pharmacotherapy should be initiated.

Disclosure

Dr. Goldstein reports that he serves on the gynecology advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and TAP Pharmaceuticals.

1. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1-129.

2. Physician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2003.

3. Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:526-528.

4. Position statement: executive summary. The Writing Group for the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD). Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2004;4:7-12

5. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.

6. Kanis JA, Johnell O, Black DM, et al. Effect of raloxifene on the risk of new vertebral fracture in post-menopausal women with osteopenia or osteoporosis: a reanalysis of the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation trial. Bone. 2003;3:293-300

7. Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202

8. Siris E, Miller P, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA. 2001;286:2815-2822

9. Miller PD, Barlas S, Brenneman SK, et al. An approach to identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1113-1120

1. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1-129.

2. Physician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2003.

3. Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:526-528.

4. Position statement: executive summary. The Writing Group for the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD). Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2004;4:7-12

5. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.

6. Kanis JA, Johnell O, Black DM, et al. Effect of raloxifene on the risk of new vertebral fracture in post-menopausal women with osteopenia or osteoporosis: a reanalysis of the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation trial. Bone. 2003;3:293-300

7. Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202

8. Siris E, Miller P, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA. 2001;286:2815-2822

9. Miller PD, Barlas S, Brenneman SK, et al. An approach to identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1113-1120