User login

In the first dose-response meta-analysis focusing on antipsychotic-induced weight gain, researchers provide data on the trajectory of this risk associated with individual agents.

Investigators analyzed 52 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) encompassing more than 22,500 participants with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics. They found that, with the exception of aripiprazole long-acting injectable (LAI), all of the other antipsychotics has significant dose-response effect on weight gain. Furthermore, weight gain occurred with some antipsychotics even at relatively low doses.

“We found significant dose-response associations for weight and metabolic variables, with a unique signature for each antipsychotic,” write the investigators, led by Michel Sabé, MD, of the division of adult psychiatry, department of psychiatry, Geneva University Hospitals.

“Despite several limitations, including the limited number of available studies, our results may provide useful information for preventing weight gain and metabolic disturbances by adapting antipsychotic doses,” they add.

The study was published online in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Balancing risks and benefits

Antipsychotics are first-line therapy for schizophrenia and are associated with weight gain, lipid disturbances, and glucose dysregulation – especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), which can lead to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Given that people with schizophrenia also tend to have lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk factors, it’s important to find “a balance between beneficial and adverse effects of antipsychotics,” the investigators note

The question of whether weight gain and metabolic dysregulation are dose-dependent “remains controversial.” The effect of specific SGAs on weight gain has been investigated, but only one study has been conducted using a dose-response meta-analysis, and that study did not address metabolic disturbance.

The investigators conducted a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of fixed-dose randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic disturbance in adults with acute schizophrenia.

To be included in the analysis, RCTs had to focus on adult patients with schizophrenia or related disorders and include a placebo as a comparator to the drug.

Studies involved only short-term administration of antipsychotics (2-13 weeks) rather than maintenance therapy.

The mean (SD) change in weight (body weight and/or body mass index) between baseline and the study endpoint constituted the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes including changes in metabolic parameters.

The researchers characterized the dose-response relationship using a nonlinear restricted cubic spline model, with three “knots” located at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of overall dose distribution.

They also calculated dose-response curves and estimated 50% and 95% effective doses (ED50 and ED95, respectively), extracted from the estimated dose-response curves for each antipsychotic.

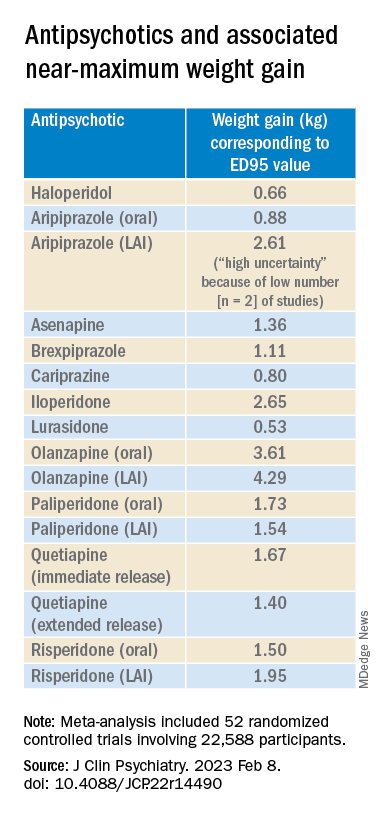

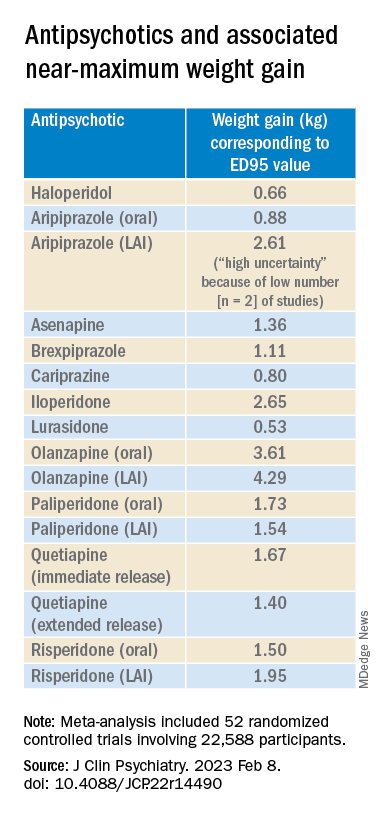

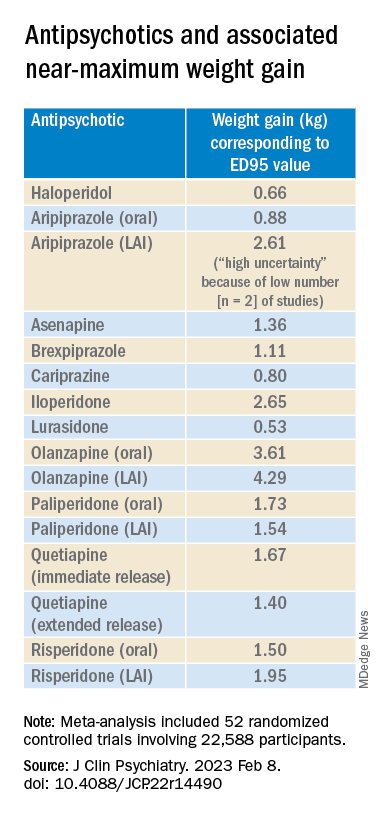

The researchers then calculated the weight gain at each effective dose (ED50 and ED95) in milligrams and the weight gain corresponding to the ED95 value in kilograms.

Shared decision-making

Of 6,812 citations, the researchers selected 52 RCTs that met inclusion criteria (n = 22,588 participants, with 16,311 receiving antipsychotics and 6,277 receiving placebo; mean age, 38.5 years, 69.2% male). The studies were conducted between1996 and 2021.

The risk for bias in most studies was “low,” although 21% of the studies “presented a high risk.”

With the exception of aripiprazole LAI, all of the other antipsychotics had a “significant dose-response” association with weight.

For example, oral aripiprazole exhibited a significant dose-response association for weight, but there was no significant association found for aripiprazole LAI (c2 = 8.744; P = .0126 vs. c2 = 3.107; P = .2115). However, both curves were still ascending at maximum doses, the authors note.

Metabolically neutral

Antipsychotics with a decreasing or quasi-parabolic dose-response curve for weight included brexpiprazole, cariprazine, haloperidol, lurasidone, and quetiapine ER: for these antipsychotics, the ED95 weight gain ranged from 0.53 kg to 1.40 kg.

These antipsychotics “reach their weight gain ED95 at relatively low median effective doses, and higher doses, which mostly correspond to near-maximum effective doses, may even be associated with less weight gain,” the authors note.

In addition, only doses higher than the near-maximum effective dose of brexpiprazole were associated with a small increase in total cholesterol. And cariprazine presented “significantly decreasing curves” at higher doses for LDL cholesterol.

With the exception of quetiapine, this group of medications might be regarded as “metabolically neutral” in terms of weight gain and metabolic disturbances.

Antipsychotics with a plateau-shaped curve were asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone LAI, quetiapine IR, and risperidone, with a weight gain ED95 ranging from 1.36 to 2.65 kg.

Aripiprazole and olanzapine (oral and LAI formulations), as well as risperidone LAI and oral paliperidone, presented weight gain curves that continued climbing at higher doses (especially olanzapine). However, the drugs have different metabolic profiles, ranging from 0.88 kg ED95 for oral aripiprazole to 4.29 kg for olanzapine LAI.

Olanzapine had the most pronounced weight gain, in addition to associations with all metabolic outcomes.

For some drugs with important metabolic side effects, “a lower dose might provide a better combination of high efficacy and reduced metabolic side effects,” the authors write.

The findings might “provide additional information for clinicians aiming to determine the most suitable dose to prevent weight gain and metabolic disturbance in a shared decision-making process with their patients,” they note.

The results add to “existing concerns about the use of olanzapine as a first-line drug,” they add.

Lowest effective dose

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said clinicians “not infrequently increase doses to achieve better symptom control, [but] this decision should be informed by the additional observation herein that the increase in those could be accompanied by weight increase.”

Moreover, many patients “take concomitant medications that could possibly increase the bioavailability of antipsychotics, which may also increase the risk for weight gain,” said Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto. He was not involved with this study.

“These data provide a reason to believe that for many people antipsychotic-associated weight gain could be mitigated by using the lowest effective dose, and rather than censor the use of some medications out of concern for weight gain, perhaps using the lowest effective dose of the medication will provide the opportunity for mitigation,” he added. “So I think it really guides clinicians to provide the lowest effective dose as a potential therapeutic and preventive strategy.”

The study received no financial support. Dr. Sabé reports no relevant financial relationships. Three coauthors report relationships with industry; the full list is contained in the original article.

Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. He has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie, and Atai Life Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the first dose-response meta-analysis focusing on antipsychotic-induced weight gain, researchers provide data on the trajectory of this risk associated with individual agents.

Investigators analyzed 52 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) encompassing more than 22,500 participants with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics. They found that, with the exception of aripiprazole long-acting injectable (LAI), all of the other antipsychotics has significant dose-response effect on weight gain. Furthermore, weight gain occurred with some antipsychotics even at relatively low doses.

“We found significant dose-response associations for weight and metabolic variables, with a unique signature for each antipsychotic,” write the investigators, led by Michel Sabé, MD, of the division of adult psychiatry, department of psychiatry, Geneva University Hospitals.

“Despite several limitations, including the limited number of available studies, our results may provide useful information for preventing weight gain and metabolic disturbances by adapting antipsychotic doses,” they add.

The study was published online in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Balancing risks and benefits

Antipsychotics are first-line therapy for schizophrenia and are associated with weight gain, lipid disturbances, and glucose dysregulation – especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), which can lead to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Given that people with schizophrenia also tend to have lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk factors, it’s important to find “a balance between beneficial and adverse effects of antipsychotics,” the investigators note

The question of whether weight gain and metabolic dysregulation are dose-dependent “remains controversial.” The effect of specific SGAs on weight gain has been investigated, but only one study has been conducted using a dose-response meta-analysis, and that study did not address metabolic disturbance.

The investigators conducted a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of fixed-dose randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic disturbance in adults with acute schizophrenia.

To be included in the analysis, RCTs had to focus on adult patients with schizophrenia or related disorders and include a placebo as a comparator to the drug.

Studies involved only short-term administration of antipsychotics (2-13 weeks) rather than maintenance therapy.

The mean (SD) change in weight (body weight and/or body mass index) between baseline and the study endpoint constituted the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes including changes in metabolic parameters.

The researchers characterized the dose-response relationship using a nonlinear restricted cubic spline model, with three “knots” located at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of overall dose distribution.

They also calculated dose-response curves and estimated 50% and 95% effective doses (ED50 and ED95, respectively), extracted from the estimated dose-response curves for each antipsychotic.

The researchers then calculated the weight gain at each effective dose (ED50 and ED95) in milligrams and the weight gain corresponding to the ED95 value in kilograms.

Shared decision-making

Of 6,812 citations, the researchers selected 52 RCTs that met inclusion criteria (n = 22,588 participants, with 16,311 receiving antipsychotics and 6,277 receiving placebo; mean age, 38.5 years, 69.2% male). The studies were conducted between1996 and 2021.

The risk for bias in most studies was “low,” although 21% of the studies “presented a high risk.”

With the exception of aripiprazole LAI, all of the other antipsychotics had a “significant dose-response” association with weight.

For example, oral aripiprazole exhibited a significant dose-response association for weight, but there was no significant association found for aripiprazole LAI (c2 = 8.744; P = .0126 vs. c2 = 3.107; P = .2115). However, both curves were still ascending at maximum doses, the authors note.

Metabolically neutral

Antipsychotics with a decreasing or quasi-parabolic dose-response curve for weight included brexpiprazole, cariprazine, haloperidol, lurasidone, and quetiapine ER: for these antipsychotics, the ED95 weight gain ranged from 0.53 kg to 1.40 kg.

These antipsychotics “reach their weight gain ED95 at relatively low median effective doses, and higher doses, which mostly correspond to near-maximum effective doses, may even be associated with less weight gain,” the authors note.

In addition, only doses higher than the near-maximum effective dose of brexpiprazole were associated with a small increase in total cholesterol. And cariprazine presented “significantly decreasing curves” at higher doses for LDL cholesterol.

With the exception of quetiapine, this group of medications might be regarded as “metabolically neutral” in terms of weight gain and metabolic disturbances.

Antipsychotics with a plateau-shaped curve were asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone LAI, quetiapine IR, and risperidone, with a weight gain ED95 ranging from 1.36 to 2.65 kg.

Aripiprazole and olanzapine (oral and LAI formulations), as well as risperidone LAI and oral paliperidone, presented weight gain curves that continued climbing at higher doses (especially olanzapine). However, the drugs have different metabolic profiles, ranging from 0.88 kg ED95 for oral aripiprazole to 4.29 kg for olanzapine LAI.

Olanzapine had the most pronounced weight gain, in addition to associations with all metabolic outcomes.

For some drugs with important metabolic side effects, “a lower dose might provide a better combination of high efficacy and reduced metabolic side effects,” the authors write.

The findings might “provide additional information for clinicians aiming to determine the most suitable dose to prevent weight gain and metabolic disturbance in a shared decision-making process with their patients,” they note.

The results add to “existing concerns about the use of olanzapine as a first-line drug,” they add.

Lowest effective dose

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said clinicians “not infrequently increase doses to achieve better symptom control, [but] this decision should be informed by the additional observation herein that the increase in those could be accompanied by weight increase.”

Moreover, many patients “take concomitant medications that could possibly increase the bioavailability of antipsychotics, which may also increase the risk for weight gain,” said Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto. He was not involved with this study.

“These data provide a reason to believe that for many people antipsychotic-associated weight gain could be mitigated by using the lowest effective dose, and rather than censor the use of some medications out of concern for weight gain, perhaps using the lowest effective dose of the medication will provide the opportunity for mitigation,” he added. “So I think it really guides clinicians to provide the lowest effective dose as a potential therapeutic and preventive strategy.”

The study received no financial support. Dr. Sabé reports no relevant financial relationships. Three coauthors report relationships with industry; the full list is contained in the original article.

Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. He has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie, and Atai Life Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the first dose-response meta-analysis focusing on antipsychotic-induced weight gain, researchers provide data on the trajectory of this risk associated with individual agents.

Investigators analyzed 52 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) encompassing more than 22,500 participants with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics. They found that, with the exception of aripiprazole long-acting injectable (LAI), all of the other antipsychotics has significant dose-response effect on weight gain. Furthermore, weight gain occurred with some antipsychotics even at relatively low doses.

“We found significant dose-response associations for weight and metabolic variables, with a unique signature for each antipsychotic,” write the investigators, led by Michel Sabé, MD, of the division of adult psychiatry, department of psychiatry, Geneva University Hospitals.

“Despite several limitations, including the limited number of available studies, our results may provide useful information for preventing weight gain and metabolic disturbances by adapting antipsychotic doses,” they add.

The study was published online in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Balancing risks and benefits

Antipsychotics are first-line therapy for schizophrenia and are associated with weight gain, lipid disturbances, and glucose dysregulation – especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), which can lead to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Given that people with schizophrenia also tend to have lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk factors, it’s important to find “a balance between beneficial and adverse effects of antipsychotics,” the investigators note

The question of whether weight gain and metabolic dysregulation are dose-dependent “remains controversial.” The effect of specific SGAs on weight gain has been investigated, but only one study has been conducted using a dose-response meta-analysis, and that study did not address metabolic disturbance.

The investigators conducted a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of fixed-dose randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic disturbance in adults with acute schizophrenia.

To be included in the analysis, RCTs had to focus on adult patients with schizophrenia or related disorders and include a placebo as a comparator to the drug.

Studies involved only short-term administration of antipsychotics (2-13 weeks) rather than maintenance therapy.

The mean (SD) change in weight (body weight and/or body mass index) between baseline and the study endpoint constituted the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes including changes in metabolic parameters.

The researchers characterized the dose-response relationship using a nonlinear restricted cubic spline model, with three “knots” located at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of overall dose distribution.

They also calculated dose-response curves and estimated 50% and 95% effective doses (ED50 and ED95, respectively), extracted from the estimated dose-response curves for each antipsychotic.

The researchers then calculated the weight gain at each effective dose (ED50 and ED95) in milligrams and the weight gain corresponding to the ED95 value in kilograms.

Shared decision-making

Of 6,812 citations, the researchers selected 52 RCTs that met inclusion criteria (n = 22,588 participants, with 16,311 receiving antipsychotics and 6,277 receiving placebo; mean age, 38.5 years, 69.2% male). The studies were conducted between1996 and 2021.

The risk for bias in most studies was “low,” although 21% of the studies “presented a high risk.”

With the exception of aripiprazole LAI, all of the other antipsychotics had a “significant dose-response” association with weight.

For example, oral aripiprazole exhibited a significant dose-response association for weight, but there was no significant association found for aripiprazole LAI (c2 = 8.744; P = .0126 vs. c2 = 3.107; P = .2115). However, both curves were still ascending at maximum doses, the authors note.

Metabolically neutral

Antipsychotics with a decreasing or quasi-parabolic dose-response curve for weight included brexpiprazole, cariprazine, haloperidol, lurasidone, and quetiapine ER: for these antipsychotics, the ED95 weight gain ranged from 0.53 kg to 1.40 kg.

These antipsychotics “reach their weight gain ED95 at relatively low median effective doses, and higher doses, which mostly correspond to near-maximum effective doses, may even be associated with less weight gain,” the authors note.

In addition, only doses higher than the near-maximum effective dose of brexpiprazole were associated with a small increase in total cholesterol. And cariprazine presented “significantly decreasing curves” at higher doses for LDL cholesterol.

With the exception of quetiapine, this group of medications might be regarded as “metabolically neutral” in terms of weight gain and metabolic disturbances.

Antipsychotics with a plateau-shaped curve were asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone LAI, quetiapine IR, and risperidone, with a weight gain ED95 ranging from 1.36 to 2.65 kg.

Aripiprazole and olanzapine (oral and LAI formulations), as well as risperidone LAI and oral paliperidone, presented weight gain curves that continued climbing at higher doses (especially olanzapine). However, the drugs have different metabolic profiles, ranging from 0.88 kg ED95 for oral aripiprazole to 4.29 kg for olanzapine LAI.

Olanzapine had the most pronounced weight gain, in addition to associations with all metabolic outcomes.

For some drugs with important metabolic side effects, “a lower dose might provide a better combination of high efficacy and reduced metabolic side effects,” the authors write.

The findings might “provide additional information for clinicians aiming to determine the most suitable dose to prevent weight gain and metabolic disturbance in a shared decision-making process with their patients,” they note.

The results add to “existing concerns about the use of olanzapine as a first-line drug,” they add.

Lowest effective dose

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said clinicians “not infrequently increase doses to achieve better symptom control, [but] this decision should be informed by the additional observation herein that the increase in those could be accompanied by weight increase.”

Moreover, many patients “take concomitant medications that could possibly increase the bioavailability of antipsychotics, which may also increase the risk for weight gain,” said Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto. He was not involved with this study.

“These data provide a reason to believe that for many people antipsychotic-associated weight gain could be mitigated by using the lowest effective dose, and rather than censor the use of some medications out of concern for weight gain, perhaps using the lowest effective dose of the medication will provide the opportunity for mitigation,” he added. “So I think it really guides clinicians to provide the lowest effective dose as a potential therapeutic and preventive strategy.”

The study received no financial support. Dr. Sabé reports no relevant financial relationships. Three coauthors report relationships with industry; the full list is contained in the original article.

Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. He has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie, and Atai Life Sciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY