User login

The rate of placenta accreta has been rising, almost certainly as a consequence of the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is estimated that morbidly adherent placenta (placenta accreta, increta, and percreta) occurs today in approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies. Women who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other uterine surgery, such as myomectomy, are at higher risk.

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is associated with significant hemorrhage and morbidity – not only in cases of attempted placental removal, which is usually not advisable, but also in cases of cesarean hysterectomy. Cesarean hysterectomy is technically complex and completely different from other hysterectomies. The abnormal vasculature of MAP requires intricate, stepwise, vessel-by-vessel dissection and not only the uterine artery ligation that is the focus in hysterectomies performed for other indications.

In the last several years, we have demonstrated improved outcomes with such an approach at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In 2014, we instituted a multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program for patients with MAP and others at high risk of intrapartum and postpartum complications. The program brings together obstetric anesthesiologists, the blood bank staff, the neonatal and surgical intensive care unit staff, vascular surgeons, perinatologists, interventional radiologists, urologists, and others.

Since the program was implemented, we have reduced our transfusion rate in patients with MAP by more than 60% while caring for increasing numbers of patients with the condition. We also have reduced the intensive care unit admission rate and improved overall surgical morbidity, including bladder complications. Moreover, our multidisciplinary approach is allowing us to develop more algorithms for management and to selectively take conservative approaches while also allowing us to lay the groundwork for future research.

The patients at risk

Anticipation is important: Identifying patient populations at high risk – and then evaluating individual risks – is essential for the prevention of delivery complications and the reduction of maternal morbidity.

Having had multiple cesarean deliveries – especially in pregnancies involving placenta previa – is one of the most important risk factors for developing MAP. One prospective cohort study of more than 30,000 women in 19 academic centers who had had cesarean deliveries found that, in cases of placenta previa, the risk of placenta accreta went from 3% after one cesarean delivery to 67% after five or more cesarean deliveries (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jun;107[6]:1226-32). Placenta accreta was defined in this study as the placenta’s being adherent to the uterine wall without easy separation. This definition included all forms of MAP.

Even without a history of placenta previa, patients who have had multiple cesarean deliveries – and developed consequent myometrial damage and scarring – should be evaluated for placental location during future pregnancies, as should patients who have had a myomectomy. A placenta that is anteriorly located in a patient who had a prior classical cesarean incision should also be thoroughly investigated. Overall, there is a risk of MAP whenever the placenta attaches to an area of uterine scarring.

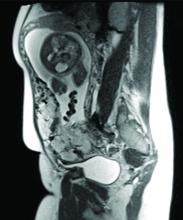

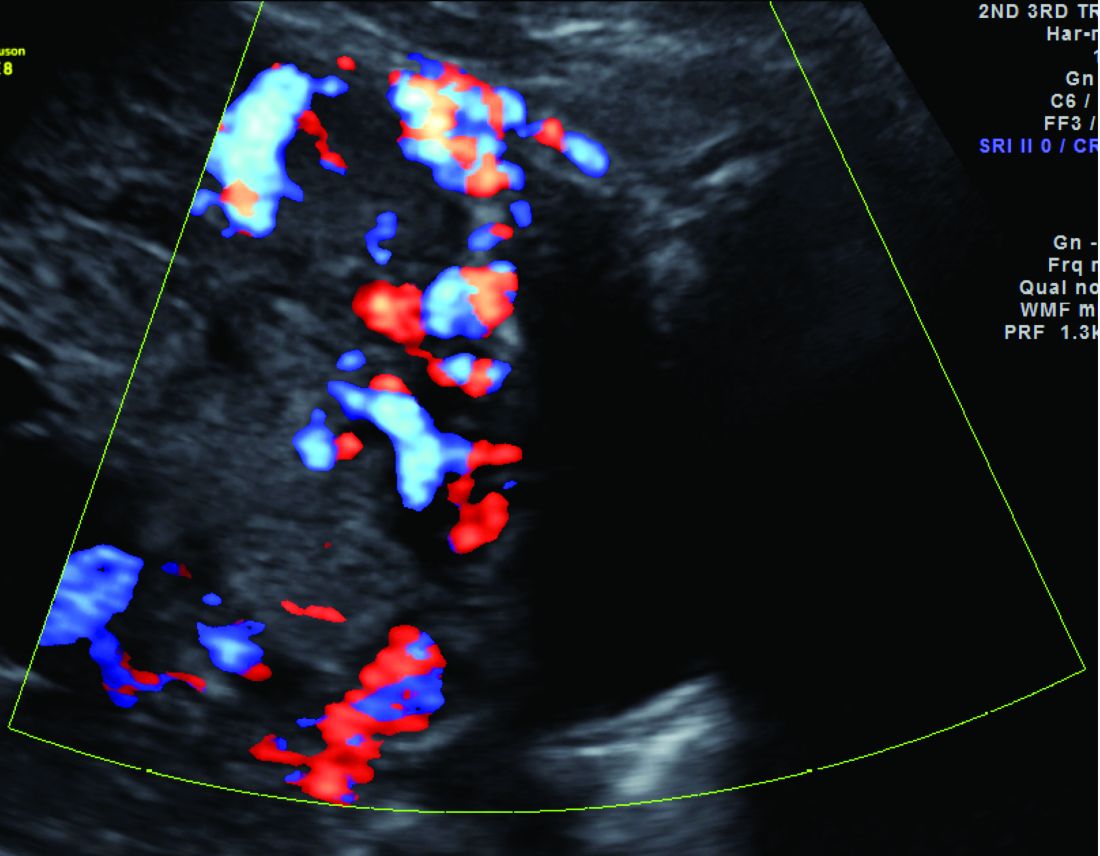

Diagnosis of MAP can be made – as best as is currently possible – by ultrasonography or by MRI, the latter of which is performed in high-risk or ambiguous cases to look more closely at the depth of placental growth.

Our outcomes and process

In our complex obstetric surgery program, we identify and evaluate patients at risk for developing MAP and also prepare comprehensive surgical plans. Each individual’s plan addresses the optimal timing of and conditions for delivery, how the patient and the team should prepare for high-quality perioperative care, and how possible complications and emergency surgery should be handled, such as who should be called in the case of emergency preterm delivery.

Indeed, research has shown that the value of a multidisciplinary approach is greatest when MAP is identified or suspected before delivery. For instance, investigators who analyzed the pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta in Utah over a 12-year period found that cases managed by a multidisciplinary care team had a 50% risk reduction for early morbidities, compared with cases managed with standard obstetric care. The benefits were even greater when placenta accreta (defined in the study to include the spectrum of MAP) was suspected before delivery; this group had a nearly 80% risk reduction with multidisciplinary care (Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;117[2 Pt 1]:331-7).

We recently compared our outcomes before and after the multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program was established. For patients with MAP, estimated blood loss has decreased by 40%, and the use of blood products has fallen by 60%-70%, with a corresponding reduction in intensive care unit admission. Moreover, our bladder complication rate fell to 6% after program implementation. This and our reoperation rate, among other outcomes, are lower than published rates from other similar medical centers that use a multidisciplinary approach.

We strive to have two surgeons in the operating room – either two senior surgeons or one senior surgeon and one junior surgeon – as well as a separate “operation supervisor” who monitors blood loss (volume and sources), vital signs, and other clinical points and who is continually thinking about next steps. The operation supervisor is not necessarily a third surgeon but could be an experienced surgical nurse or an obstetric anesthesiologist.

Obstetric anesthesiologists and the blood bank staff have proven to be especially important parts of our multidisciplinary team. At 28-30 weeks’ gestation, each patient has an anesthesia consult and also is tested for blood type and screened for antibodies. Patients also are tested for anemia at this time so that it may be corrected if necessary before surgery.

As determined by our multidisciplinary team, all deliveries are performed under general anesthesia, with early placement of both a central venous catheter and a peripheral arterial line to enable rapid transfusions of blood or fluid. Patients are routinely placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, which enables direct access to the vagina and better assessment of vaginal bleeding. And, when significant blood loss is anticipated, the intensive care unit team prepares a bed, and our surgical colleagues are alerted.

Conservative management

Interest in conservative management – in avoiding hysterectomy when it is deemed to carry much higher risks of hemorrhage or injury to adjacent tissue than leaving the placenta in situ – has resurged in Europe. However, research is still in its infancy regarding the benefits and safety of conservative management, and clear guidance about eligibility and contraindications is still needed (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:755-60).

One patient with the placenta left in situ had an urgent hysterectomy within 2 hours of delivery because of vaginal bleeding, with the total blood loss within an acceptable range and without complications. Another required an urgent hysterectomy 6 weeks after delivery because of severe hemorrhaging. The remaining two had nonurgent hysterectomies at least 6 weeks later, with the total blood loss minimized by the period of recovery and by some spontaneous regression of the placental bulk.

As we have gained more experience with conservative management and spent more time shaping multidisciplinary protocols, it has become clear to us that programs must have in place excellent protocols and strict rules for monitoring and follow-up given the risks of life-threatening hemorrhage and other significant complications when the placenta is left in situ.

A conservative approach also may be preferred by women who desire fertility preservation. Currently, in such cases, we have performed segmental or local resection with uterine repair. We do not yet have any data on subsequent pregnancies.

Research conducted within the growing sphere of complex obstetric surgery should help us to improve decision making and management of MAP. For instance, we need better imaging techniques to more accurately predict MAP and show us the degree of placental invasion. A study published several years ago that blinded sonographers from information about patients’ clinical history and risk factors found significant interobserver variability for the diagnosis of placenta accreta and sensitivity (53.5%) that was significantly lower than previously described (J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Dec;33[12]:2153-8).

Dr. Turan’s stepwise dissection

In addition to a multidisciplinary approach, a meticulous dissection technique can help drive improved outcomes. The morbidly adherent placenta is a hypervascular organ; it recruits a host of blood vessels, largely from the vaginal arteries, superior vesical arteries, and vaginal venous plexus.

Moreover, in most cases, this vascular remodeling exacerbates vascular patterns that are distorted to begin with as a result of the scarring process following previous uterine surgery. Scarred tissue is already hypervascular.

I have found that most of the blood loss during hysterectomy occurs during dissection of the poorly defined interface between the lower uterine segment and the bladder and not during dissection of the uterine artery. Identification of the cleavage plane and ligation of each individual vessel using a bipolar or small hand-held desiccation device are key in reducing blood loss. This can take a significant amount of time but is well worth it.

Managing super morbid obesity

The number of pregnant women who require challenging obstetric surgeries is increasing, and this includes women with super morbid obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2 or weight greater than 350 lb). Cesarean deliveries for these patients have proven to be much more complicated, involving special anesthesia needs, for instance.

In addition to women with placental implantation abnormalities (MAP and placenta previa, for instance) and those with extreme morbid obesity, the complex obstetric surgery program also aims to manage patients with increased risk for surgical morbidities based on previous surgery, patients whose fetuses require ex utero intrapartum treatment, and women who require abdominal cerclage.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The rate of placenta accreta has been rising, almost certainly as a consequence of the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is estimated that morbidly adherent placenta (placenta accreta, increta, and percreta) occurs today in approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies. Women who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other uterine surgery, such as myomectomy, are at higher risk.

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is associated with significant hemorrhage and morbidity – not only in cases of attempted placental removal, which is usually not advisable, but also in cases of cesarean hysterectomy. Cesarean hysterectomy is technically complex and completely different from other hysterectomies. The abnormal vasculature of MAP requires intricate, stepwise, vessel-by-vessel dissection and not only the uterine artery ligation that is the focus in hysterectomies performed for other indications.

In the last several years, we have demonstrated improved outcomes with such an approach at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In 2014, we instituted a multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program for patients with MAP and others at high risk of intrapartum and postpartum complications. The program brings together obstetric anesthesiologists, the blood bank staff, the neonatal and surgical intensive care unit staff, vascular surgeons, perinatologists, interventional radiologists, urologists, and others.

Since the program was implemented, we have reduced our transfusion rate in patients with MAP by more than 60% while caring for increasing numbers of patients with the condition. We also have reduced the intensive care unit admission rate and improved overall surgical morbidity, including bladder complications. Moreover, our multidisciplinary approach is allowing us to develop more algorithms for management and to selectively take conservative approaches while also allowing us to lay the groundwork for future research.

The patients at risk

Anticipation is important: Identifying patient populations at high risk – and then evaluating individual risks – is essential for the prevention of delivery complications and the reduction of maternal morbidity.

Having had multiple cesarean deliveries – especially in pregnancies involving placenta previa – is one of the most important risk factors for developing MAP. One prospective cohort study of more than 30,000 women in 19 academic centers who had had cesarean deliveries found that, in cases of placenta previa, the risk of placenta accreta went from 3% after one cesarean delivery to 67% after five or more cesarean deliveries (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jun;107[6]:1226-32). Placenta accreta was defined in this study as the placenta’s being adherent to the uterine wall without easy separation. This definition included all forms of MAP.

Even without a history of placenta previa, patients who have had multiple cesarean deliveries – and developed consequent myometrial damage and scarring – should be evaluated for placental location during future pregnancies, as should patients who have had a myomectomy. A placenta that is anteriorly located in a patient who had a prior classical cesarean incision should also be thoroughly investigated. Overall, there is a risk of MAP whenever the placenta attaches to an area of uterine scarring.

Diagnosis of MAP can be made – as best as is currently possible – by ultrasonography or by MRI, the latter of which is performed in high-risk or ambiguous cases to look more closely at the depth of placental growth.

Our outcomes and process

In our complex obstetric surgery program, we identify and evaluate patients at risk for developing MAP and also prepare comprehensive surgical plans. Each individual’s plan addresses the optimal timing of and conditions for delivery, how the patient and the team should prepare for high-quality perioperative care, and how possible complications and emergency surgery should be handled, such as who should be called in the case of emergency preterm delivery.

Indeed, research has shown that the value of a multidisciplinary approach is greatest when MAP is identified or suspected before delivery. For instance, investigators who analyzed the pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta in Utah over a 12-year period found that cases managed by a multidisciplinary care team had a 50% risk reduction for early morbidities, compared with cases managed with standard obstetric care. The benefits were even greater when placenta accreta (defined in the study to include the spectrum of MAP) was suspected before delivery; this group had a nearly 80% risk reduction with multidisciplinary care (Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;117[2 Pt 1]:331-7).

We recently compared our outcomes before and after the multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program was established. For patients with MAP, estimated blood loss has decreased by 40%, and the use of blood products has fallen by 60%-70%, with a corresponding reduction in intensive care unit admission. Moreover, our bladder complication rate fell to 6% after program implementation. This and our reoperation rate, among other outcomes, are lower than published rates from other similar medical centers that use a multidisciplinary approach.

We strive to have two surgeons in the operating room – either two senior surgeons or one senior surgeon and one junior surgeon – as well as a separate “operation supervisor” who monitors blood loss (volume and sources), vital signs, and other clinical points and who is continually thinking about next steps. The operation supervisor is not necessarily a third surgeon but could be an experienced surgical nurse or an obstetric anesthesiologist.

Obstetric anesthesiologists and the blood bank staff have proven to be especially important parts of our multidisciplinary team. At 28-30 weeks’ gestation, each patient has an anesthesia consult and also is tested for blood type and screened for antibodies. Patients also are tested for anemia at this time so that it may be corrected if necessary before surgery.

As determined by our multidisciplinary team, all deliveries are performed under general anesthesia, with early placement of both a central venous catheter and a peripheral arterial line to enable rapid transfusions of blood or fluid. Patients are routinely placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, which enables direct access to the vagina and better assessment of vaginal bleeding. And, when significant blood loss is anticipated, the intensive care unit team prepares a bed, and our surgical colleagues are alerted.

Conservative management

Interest in conservative management – in avoiding hysterectomy when it is deemed to carry much higher risks of hemorrhage or injury to adjacent tissue than leaving the placenta in situ – has resurged in Europe. However, research is still in its infancy regarding the benefits and safety of conservative management, and clear guidance about eligibility and contraindications is still needed (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:755-60).

One patient with the placenta left in situ had an urgent hysterectomy within 2 hours of delivery because of vaginal bleeding, with the total blood loss within an acceptable range and without complications. Another required an urgent hysterectomy 6 weeks after delivery because of severe hemorrhaging. The remaining two had nonurgent hysterectomies at least 6 weeks later, with the total blood loss minimized by the period of recovery and by some spontaneous regression of the placental bulk.

As we have gained more experience with conservative management and spent more time shaping multidisciplinary protocols, it has become clear to us that programs must have in place excellent protocols and strict rules for monitoring and follow-up given the risks of life-threatening hemorrhage and other significant complications when the placenta is left in situ.

A conservative approach also may be preferred by women who desire fertility preservation. Currently, in such cases, we have performed segmental or local resection with uterine repair. We do not yet have any data on subsequent pregnancies.

Research conducted within the growing sphere of complex obstetric surgery should help us to improve decision making and management of MAP. For instance, we need better imaging techniques to more accurately predict MAP and show us the degree of placental invasion. A study published several years ago that blinded sonographers from information about patients’ clinical history and risk factors found significant interobserver variability for the diagnosis of placenta accreta and sensitivity (53.5%) that was significantly lower than previously described (J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Dec;33[12]:2153-8).

Dr. Turan’s stepwise dissection

In addition to a multidisciplinary approach, a meticulous dissection technique can help drive improved outcomes. The morbidly adherent placenta is a hypervascular organ; it recruits a host of blood vessels, largely from the vaginal arteries, superior vesical arteries, and vaginal venous plexus.

Moreover, in most cases, this vascular remodeling exacerbates vascular patterns that are distorted to begin with as a result of the scarring process following previous uterine surgery. Scarred tissue is already hypervascular.

I have found that most of the blood loss during hysterectomy occurs during dissection of the poorly defined interface between the lower uterine segment and the bladder and not during dissection of the uterine artery. Identification of the cleavage plane and ligation of each individual vessel using a bipolar or small hand-held desiccation device are key in reducing blood loss. This can take a significant amount of time but is well worth it.

Managing super morbid obesity

The number of pregnant women who require challenging obstetric surgeries is increasing, and this includes women with super morbid obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2 or weight greater than 350 lb). Cesarean deliveries for these patients have proven to be much more complicated, involving special anesthesia needs, for instance.

In addition to women with placental implantation abnormalities (MAP and placenta previa, for instance) and those with extreme morbid obesity, the complex obstetric surgery program also aims to manage patients with increased risk for surgical morbidities based on previous surgery, patients whose fetuses require ex utero intrapartum treatment, and women who require abdominal cerclage.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The rate of placenta accreta has been rising, almost certainly as a consequence of the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is estimated that morbidly adherent placenta (placenta accreta, increta, and percreta) occurs today in approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies. Women who have had prior cesarean deliveries or other uterine surgery, such as myomectomy, are at higher risk.

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP) is associated with significant hemorrhage and morbidity – not only in cases of attempted placental removal, which is usually not advisable, but also in cases of cesarean hysterectomy. Cesarean hysterectomy is technically complex and completely different from other hysterectomies. The abnormal vasculature of MAP requires intricate, stepwise, vessel-by-vessel dissection and not only the uterine artery ligation that is the focus in hysterectomies performed for other indications.

In the last several years, we have demonstrated improved outcomes with such an approach at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In 2014, we instituted a multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program for patients with MAP and others at high risk of intrapartum and postpartum complications. The program brings together obstetric anesthesiologists, the blood bank staff, the neonatal and surgical intensive care unit staff, vascular surgeons, perinatologists, interventional radiologists, urologists, and others.

Since the program was implemented, we have reduced our transfusion rate in patients with MAP by more than 60% while caring for increasing numbers of patients with the condition. We also have reduced the intensive care unit admission rate and improved overall surgical morbidity, including bladder complications. Moreover, our multidisciplinary approach is allowing us to develop more algorithms for management and to selectively take conservative approaches while also allowing us to lay the groundwork for future research.

The patients at risk

Anticipation is important: Identifying patient populations at high risk – and then evaluating individual risks – is essential for the prevention of delivery complications and the reduction of maternal morbidity.

Having had multiple cesarean deliveries – especially in pregnancies involving placenta previa – is one of the most important risk factors for developing MAP. One prospective cohort study of more than 30,000 women in 19 academic centers who had had cesarean deliveries found that, in cases of placenta previa, the risk of placenta accreta went from 3% after one cesarean delivery to 67% after five or more cesarean deliveries (Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jun;107[6]:1226-32). Placenta accreta was defined in this study as the placenta’s being adherent to the uterine wall without easy separation. This definition included all forms of MAP.

Even without a history of placenta previa, patients who have had multiple cesarean deliveries – and developed consequent myometrial damage and scarring – should be evaluated for placental location during future pregnancies, as should patients who have had a myomectomy. A placenta that is anteriorly located in a patient who had a prior classical cesarean incision should also be thoroughly investigated. Overall, there is a risk of MAP whenever the placenta attaches to an area of uterine scarring.

Diagnosis of MAP can be made – as best as is currently possible – by ultrasonography or by MRI, the latter of which is performed in high-risk or ambiguous cases to look more closely at the depth of placental growth.

Our outcomes and process

In our complex obstetric surgery program, we identify and evaluate patients at risk for developing MAP and also prepare comprehensive surgical plans. Each individual’s plan addresses the optimal timing of and conditions for delivery, how the patient and the team should prepare for high-quality perioperative care, and how possible complications and emergency surgery should be handled, such as who should be called in the case of emergency preterm delivery.

Indeed, research has shown that the value of a multidisciplinary approach is greatest when MAP is identified or suspected before delivery. For instance, investigators who analyzed the pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta in Utah over a 12-year period found that cases managed by a multidisciplinary care team had a 50% risk reduction for early morbidities, compared with cases managed with standard obstetric care. The benefits were even greater when placenta accreta (defined in the study to include the spectrum of MAP) was suspected before delivery; this group had a nearly 80% risk reduction with multidisciplinary care (Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Feb;117[2 Pt 1]:331-7).

We recently compared our outcomes before and after the multidisciplinary complex obstetric surgery program was established. For patients with MAP, estimated blood loss has decreased by 40%, and the use of blood products has fallen by 60%-70%, with a corresponding reduction in intensive care unit admission. Moreover, our bladder complication rate fell to 6% after program implementation. This and our reoperation rate, among other outcomes, are lower than published rates from other similar medical centers that use a multidisciplinary approach.

We strive to have two surgeons in the operating room – either two senior surgeons or one senior surgeon and one junior surgeon – as well as a separate “operation supervisor” who monitors blood loss (volume and sources), vital signs, and other clinical points and who is continually thinking about next steps. The operation supervisor is not necessarily a third surgeon but could be an experienced surgical nurse or an obstetric anesthesiologist.

Obstetric anesthesiologists and the blood bank staff have proven to be especially important parts of our multidisciplinary team. At 28-30 weeks’ gestation, each patient has an anesthesia consult and also is tested for blood type and screened for antibodies. Patients also are tested for anemia at this time so that it may be corrected if necessary before surgery.

As determined by our multidisciplinary team, all deliveries are performed under general anesthesia, with early placement of both a central venous catheter and a peripheral arterial line to enable rapid transfusions of blood or fluid. Patients are routinely placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, which enables direct access to the vagina and better assessment of vaginal bleeding. And, when significant blood loss is anticipated, the intensive care unit team prepares a bed, and our surgical colleagues are alerted.

Conservative management

Interest in conservative management – in avoiding hysterectomy when it is deemed to carry much higher risks of hemorrhage or injury to adjacent tissue than leaving the placenta in situ – has resurged in Europe. However, research is still in its infancy regarding the benefits and safety of conservative management, and clear guidance about eligibility and contraindications is still needed (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:755-60).

One patient with the placenta left in situ had an urgent hysterectomy within 2 hours of delivery because of vaginal bleeding, with the total blood loss within an acceptable range and without complications. Another required an urgent hysterectomy 6 weeks after delivery because of severe hemorrhaging. The remaining two had nonurgent hysterectomies at least 6 weeks later, with the total blood loss minimized by the period of recovery and by some spontaneous regression of the placental bulk.

As we have gained more experience with conservative management and spent more time shaping multidisciplinary protocols, it has become clear to us that programs must have in place excellent protocols and strict rules for monitoring and follow-up given the risks of life-threatening hemorrhage and other significant complications when the placenta is left in situ.

A conservative approach also may be preferred by women who desire fertility preservation. Currently, in such cases, we have performed segmental or local resection with uterine repair. We do not yet have any data on subsequent pregnancies.

Research conducted within the growing sphere of complex obstetric surgery should help us to improve decision making and management of MAP. For instance, we need better imaging techniques to more accurately predict MAP and show us the degree of placental invasion. A study published several years ago that blinded sonographers from information about patients’ clinical history and risk factors found significant interobserver variability for the diagnosis of placenta accreta and sensitivity (53.5%) that was significantly lower than previously described (J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Dec;33[12]:2153-8).

Dr. Turan’s stepwise dissection

In addition to a multidisciplinary approach, a meticulous dissection technique can help drive improved outcomes. The morbidly adherent placenta is a hypervascular organ; it recruits a host of blood vessels, largely from the vaginal arteries, superior vesical arteries, and vaginal venous plexus.

Moreover, in most cases, this vascular remodeling exacerbates vascular patterns that are distorted to begin with as a result of the scarring process following previous uterine surgery. Scarred tissue is already hypervascular.

I have found that most of the blood loss during hysterectomy occurs during dissection of the poorly defined interface between the lower uterine segment and the bladder and not during dissection of the uterine artery. Identification of the cleavage plane and ligation of each individual vessel using a bipolar or small hand-held desiccation device are key in reducing blood loss. This can take a significant amount of time but is well worth it.

Managing super morbid obesity

The number of pregnant women who require challenging obstetric surgeries is increasing, and this includes women with super morbid obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2 or weight greater than 350 lb). Cesarean deliveries for these patients have proven to be much more complicated, involving special anesthesia needs, for instance.

In addition to women with placental implantation abnormalities (MAP and placenta previa, for instance) and those with extreme morbid obesity, the complex obstetric surgery program also aims to manage patients with increased risk for surgical morbidities based on previous surgery, patients whose fetuses require ex utero intrapartum treatment, and women who require abdominal cerclage.

Dr. Turan is director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.