User login

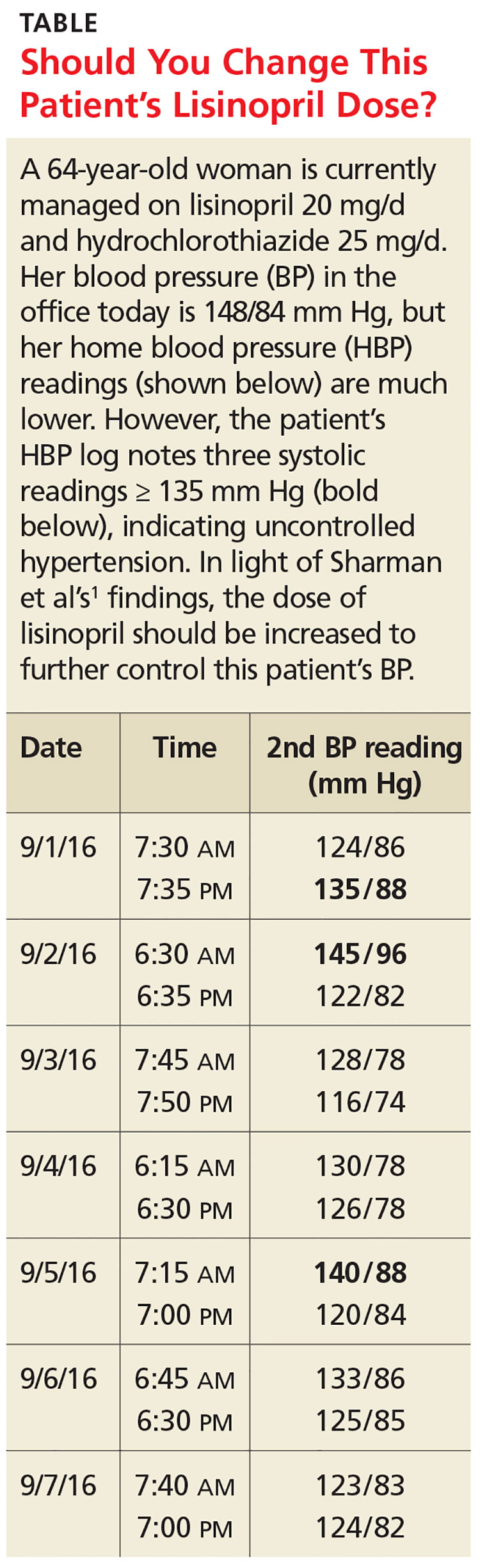

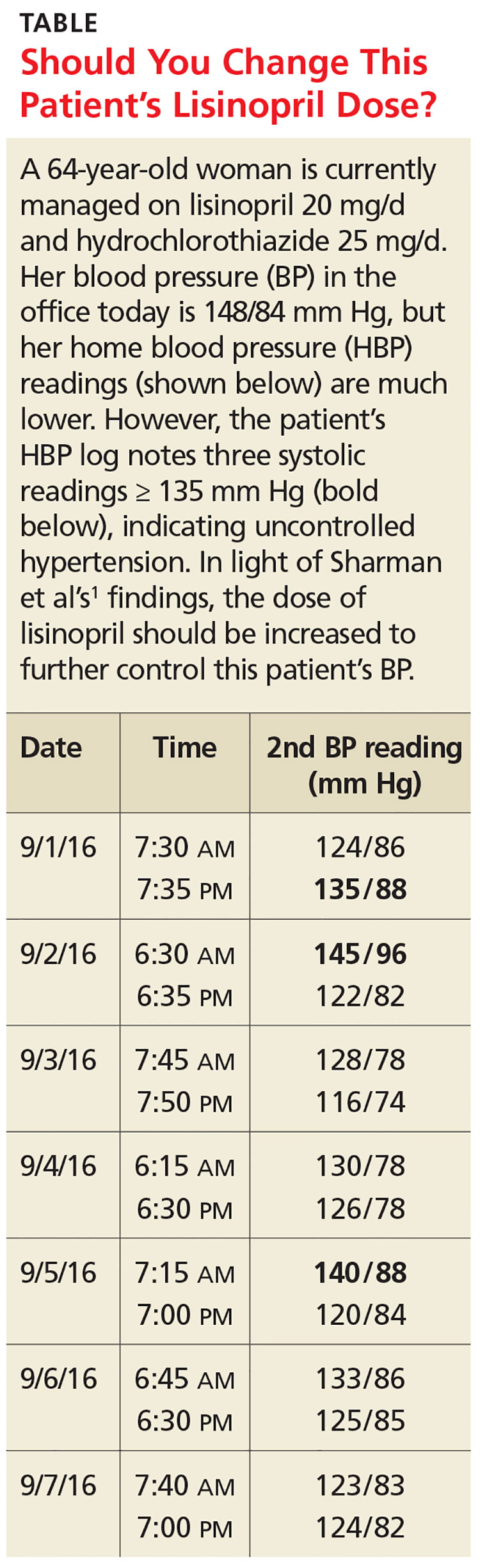

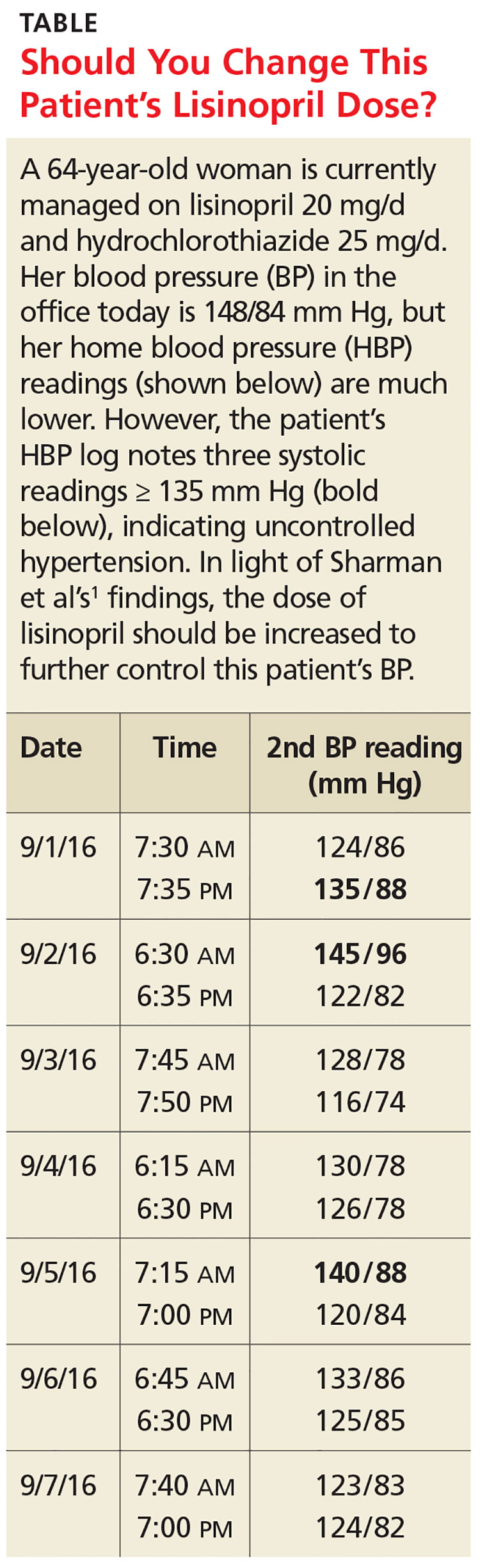

A 64-year-old woman presents to your office for a follow-up visit for her hypertension. She is currently managed on lisinopril 20 mg/d and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d without any problems. The patient’s blood pressure (BP) in the office today is 148/84 mm Hg, but her home blood pressure (HBP) readings are much lower (see Table). Should you increase her lisinopril dose today?

Hypertension has been diagnosed on the basis of office readings of BP for almost a century, but the readings can be so inaccurate that they are not useful.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) to accurately diagnose hypertension in all patients, while The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends ABPM for patients suspected of having white-coat hypertension and any patient with resistant hypertension, but ABPM is not always acceptable to patients.3-5

HBP monitoring for long-term follow-up

The European Society of Hypertension practice guideline on HBP monitoring suggests that HBP values < 130/80 mm Hg may be considered normal, while a mean HBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg is considered elevated.9 The guideline recommends HBP monitoring for three to seven days prior to a patient’s follow-up appointment, with two readings taken one to two minutes apart in the morning and evening.9 In a busy clinic, averaging all of these home values can be time-consuming.

So how can primary care providers accurately and efficiently streamline the process? This study sought to answer that question.

STUDY SUMMARY

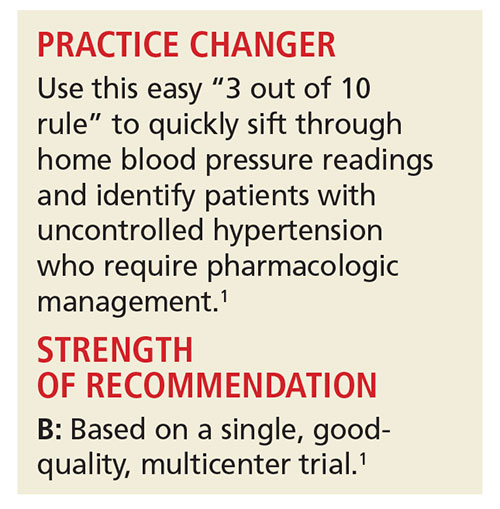

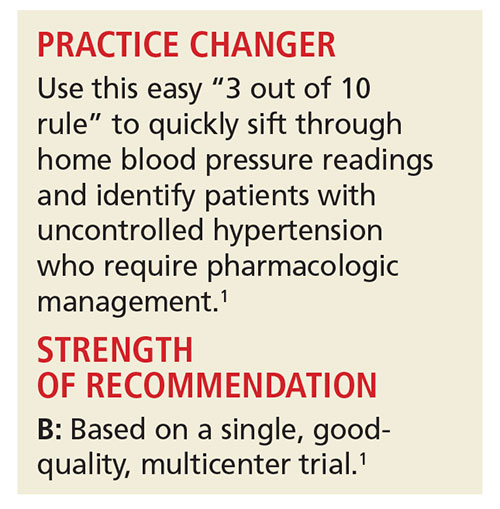

3 of 10 readings = predictive

This multicenter trial compared HBP monitoring to 24-hour ABPM in 286 patients with uncomplicated essential hypertension to determine the optimal percentage of HBP readings needed to diagnose uncontrolled BP (HBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg). Patients were included if they were diagnosed with uncomplicated hypertension, not pregnant, age 18 or older, and taking three or fewer antihypertensive medications. Patients were excluded if they had a significant abnormal left ventricular mass index (women > 59 g/m2; men > 64 g/m2), coronary artery or renal disease, secondary hypertension, serum creatinine exceeding 1.6 mg/dL, aortic valve stenosis, upper limb obstructive atherosclerosis, or BP > 180/100 mm Hg.

Approximately half of the participants were women (53%). Average BMI was 29.4 kg/m2, and the average number of hypertension medications being taken was 2.4. Medication compliance was verified by a study nurse at a clinic visit.

The patients were instructed to take two BP readings (one minute apart) at home three times daily, in the morning (between 6

The primary outcome was to determine the optimal number of systolic HBP readings above goal (135 mm Hg), from the last 10 recordings, that would best predict elevated 24-hour ABP. Secondary outcomes were various cardiovascular markers of target end-organ damage.

The researchers found that if at least three of the last 10 HBP readings were elevated (≥ 135 mm Hg systolic), the patient was likely to have hypertension on 24-hour ABPM (≥ 130 mm Hg). When patients had less than three HBP elevations out of 10 readings, their mean (± standard deviation [SD]) 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 132.7 (± 11.1) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 120.4 (± 9.8) mm Hg. When patients had three or more HBP elevations, their mean 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 143.4 (± 11.2) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 147.4 (± 10.5) mm Hg.

The positive and negative predictive values of three or more HBP elevations were 0.85 and 0.56, respectively, for a 24-hour systolic ABP of ≥ 130 mm Hg. Three elevations or more in HBP, out of the last 10 readings, was also an indicator for target organ disease assessed by aortic stiffness and increased left ventricular mass and decreased function.

The sensitivity and specificity of three or more elevations for mean 24-hour ABP systolic readings ≥ 130 mm Hg were 62% and 80%, respectively, and for 24-hour ABP daytime systolic readings ≥ 135 mm Hg were 65% and 77%, respectively.

WHAT’S NEW

Monitoring home BP can be simplified

The researchers found that HBP monitoring correlates well with ABPM and that their method provides clinicians with a simple way (three of the past 10 measurements ≥ 135 mm Hg systolic) to use HBP readings to make clinical decisions regarding BP management.

CAVEATS

BP goals are hazy, patient education is required

Conflicting information and opinions remain regarding the ideal intensive and standard BP goals in different populations.10,11 Systolic BP goals in this study (≥ 130 mm Hg for overall 24-hour ABP and ≥ 135 mm Hg for 24-hour ABP daytime readings) are recommended by some experts but are not commonly recognized goals in the United States. This study found good correlation between HBP and ABPM at these goals, and it seems likely that this correlation could be extrapolated for similar BP goals.

Other limitations are that (1) The study focused only on systolic BP goals; (2) patients in the study adhered to precise instructions on BP monitoring; HBP monitoring requires significant patient education on the proper use of the equipment and the monitoring schedule; and (3) while end-organ complication outcomes showed numerical decreases in function, the clinical significance of these reductions for patients is unclear.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost, sizing of cuffs

The cost of HBP monitors ($40-$60) has decreased significantly over time, but the devices are not always covered by insurance and may be unobtainable for some people.

Additionally, patients should be counseled on how to determine the appropriate cuff size to ensure the accuracy of the measurements. The British Hypertension Society maintains a list of validated BP devices on its website: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors.12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(10):719-722.

1. Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

2. Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, et al. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2014;32:509-517.

3. Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778-786.

4. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

5. Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Baguet JP, et al. Acceptability and tolerance of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the hypertensive patient. Blood Press Monit. 1996; 1:197-203.

6. Gaborieau V, Delarche N, Gosse P. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring versus self-measurement of blood pressure at home: correlation with target organ damage. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1919-1927.

7. Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, et al. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449-456.

8. Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary. A joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:1-9.

9. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:779-785.

10. The SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

11. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2016;352:i717.

12. British Hypertension Society. BP Monitors. http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors. Accessed June 27, 2016.

A 64-year-old woman presents to your office for a follow-up visit for her hypertension. She is currently managed on lisinopril 20 mg/d and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d without any problems. The patient’s blood pressure (BP) in the office today is 148/84 mm Hg, but her home blood pressure (HBP) readings are much lower (see Table). Should you increase her lisinopril dose today?

Hypertension has been diagnosed on the basis of office readings of BP for almost a century, but the readings can be so inaccurate that they are not useful.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) to accurately diagnose hypertension in all patients, while The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends ABPM for patients suspected of having white-coat hypertension and any patient with resistant hypertension, but ABPM is not always acceptable to patients.3-5

HBP monitoring for long-term follow-up

The European Society of Hypertension practice guideline on HBP monitoring suggests that HBP values < 130/80 mm Hg may be considered normal, while a mean HBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg is considered elevated.9 The guideline recommends HBP monitoring for three to seven days prior to a patient’s follow-up appointment, with two readings taken one to two minutes apart in the morning and evening.9 In a busy clinic, averaging all of these home values can be time-consuming.

So how can primary care providers accurately and efficiently streamline the process? This study sought to answer that question.

STUDY SUMMARY

3 of 10 readings = predictive

This multicenter trial compared HBP monitoring to 24-hour ABPM in 286 patients with uncomplicated essential hypertension to determine the optimal percentage of HBP readings needed to diagnose uncontrolled BP (HBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg). Patients were included if they were diagnosed with uncomplicated hypertension, not pregnant, age 18 or older, and taking three or fewer antihypertensive medications. Patients were excluded if they had a significant abnormal left ventricular mass index (women > 59 g/m2; men > 64 g/m2), coronary artery or renal disease, secondary hypertension, serum creatinine exceeding 1.6 mg/dL, aortic valve stenosis, upper limb obstructive atherosclerosis, or BP > 180/100 mm Hg.

Approximately half of the participants were women (53%). Average BMI was 29.4 kg/m2, and the average number of hypertension medications being taken was 2.4. Medication compliance was verified by a study nurse at a clinic visit.

The patients were instructed to take two BP readings (one minute apart) at home three times daily, in the morning (between 6

The primary outcome was to determine the optimal number of systolic HBP readings above goal (135 mm Hg), from the last 10 recordings, that would best predict elevated 24-hour ABP. Secondary outcomes were various cardiovascular markers of target end-organ damage.

The researchers found that if at least three of the last 10 HBP readings were elevated (≥ 135 mm Hg systolic), the patient was likely to have hypertension on 24-hour ABPM (≥ 130 mm Hg). When patients had less than three HBP elevations out of 10 readings, their mean (± standard deviation [SD]) 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 132.7 (± 11.1) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 120.4 (± 9.8) mm Hg. When patients had three or more HBP elevations, their mean 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 143.4 (± 11.2) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 147.4 (± 10.5) mm Hg.

The positive and negative predictive values of three or more HBP elevations were 0.85 and 0.56, respectively, for a 24-hour systolic ABP of ≥ 130 mm Hg. Three elevations or more in HBP, out of the last 10 readings, was also an indicator for target organ disease assessed by aortic stiffness and increased left ventricular mass and decreased function.

The sensitivity and specificity of three or more elevations for mean 24-hour ABP systolic readings ≥ 130 mm Hg were 62% and 80%, respectively, and for 24-hour ABP daytime systolic readings ≥ 135 mm Hg were 65% and 77%, respectively.

WHAT’S NEW

Monitoring home BP can be simplified

The researchers found that HBP monitoring correlates well with ABPM and that their method provides clinicians with a simple way (three of the past 10 measurements ≥ 135 mm Hg systolic) to use HBP readings to make clinical decisions regarding BP management.

CAVEATS

BP goals are hazy, patient education is required

Conflicting information and opinions remain regarding the ideal intensive and standard BP goals in different populations.10,11 Systolic BP goals in this study (≥ 130 mm Hg for overall 24-hour ABP and ≥ 135 mm Hg for 24-hour ABP daytime readings) are recommended by some experts but are not commonly recognized goals in the United States. This study found good correlation between HBP and ABPM at these goals, and it seems likely that this correlation could be extrapolated for similar BP goals.

Other limitations are that (1) The study focused only on systolic BP goals; (2) patients in the study adhered to precise instructions on BP monitoring; HBP monitoring requires significant patient education on the proper use of the equipment and the monitoring schedule; and (3) while end-organ complication outcomes showed numerical decreases in function, the clinical significance of these reductions for patients is unclear.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost, sizing of cuffs

The cost of HBP monitors ($40-$60) has decreased significantly over time, but the devices are not always covered by insurance and may be unobtainable for some people.

Additionally, patients should be counseled on how to determine the appropriate cuff size to ensure the accuracy of the measurements. The British Hypertension Society maintains a list of validated BP devices on its website: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors.12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(10):719-722.

A 64-year-old woman presents to your office for a follow-up visit for her hypertension. She is currently managed on lisinopril 20 mg/d and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d without any problems. The patient’s blood pressure (BP) in the office today is 148/84 mm Hg, but her home blood pressure (HBP) readings are much lower (see Table). Should you increase her lisinopril dose today?

Hypertension has been diagnosed on the basis of office readings of BP for almost a century, but the readings can be so inaccurate that they are not useful.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends the use of ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) to accurately diagnose hypertension in all patients, while The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends ABPM for patients suspected of having white-coat hypertension and any patient with resistant hypertension, but ABPM is not always acceptable to patients.3-5

HBP monitoring for long-term follow-up

The European Society of Hypertension practice guideline on HBP monitoring suggests that HBP values < 130/80 mm Hg may be considered normal, while a mean HBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg is considered elevated.9 The guideline recommends HBP monitoring for three to seven days prior to a patient’s follow-up appointment, with two readings taken one to two minutes apart in the morning and evening.9 In a busy clinic, averaging all of these home values can be time-consuming.

So how can primary care providers accurately and efficiently streamline the process? This study sought to answer that question.

STUDY SUMMARY

3 of 10 readings = predictive

This multicenter trial compared HBP monitoring to 24-hour ABPM in 286 patients with uncomplicated essential hypertension to determine the optimal percentage of HBP readings needed to diagnose uncontrolled BP (HBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg). Patients were included if they were diagnosed with uncomplicated hypertension, not pregnant, age 18 or older, and taking three or fewer antihypertensive medications. Patients were excluded if they had a significant abnormal left ventricular mass index (women > 59 g/m2; men > 64 g/m2), coronary artery or renal disease, secondary hypertension, serum creatinine exceeding 1.6 mg/dL, aortic valve stenosis, upper limb obstructive atherosclerosis, or BP > 180/100 mm Hg.

Approximately half of the participants were women (53%). Average BMI was 29.4 kg/m2, and the average number of hypertension medications being taken was 2.4. Medication compliance was verified by a study nurse at a clinic visit.

The patients were instructed to take two BP readings (one minute apart) at home three times daily, in the morning (between 6

The primary outcome was to determine the optimal number of systolic HBP readings above goal (135 mm Hg), from the last 10 recordings, that would best predict elevated 24-hour ABP. Secondary outcomes were various cardiovascular markers of target end-organ damage.

The researchers found that if at least three of the last 10 HBP readings were elevated (≥ 135 mm Hg systolic), the patient was likely to have hypertension on 24-hour ABPM (≥ 130 mm Hg). When patients had less than three HBP elevations out of 10 readings, their mean (± standard deviation [SD]) 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 132.7 (± 11.1) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 120.4 (± 9.8) mm Hg. When patients had three or more HBP elevations, their mean 24-hour ambulatory daytime systolic BP was 143.4 (± 11.2) mm Hg and their mean systolic HBP value was 147.4 (± 10.5) mm Hg.

The positive and negative predictive values of three or more HBP elevations were 0.85 and 0.56, respectively, for a 24-hour systolic ABP of ≥ 130 mm Hg. Three elevations or more in HBP, out of the last 10 readings, was also an indicator for target organ disease assessed by aortic stiffness and increased left ventricular mass and decreased function.

The sensitivity and specificity of three or more elevations for mean 24-hour ABP systolic readings ≥ 130 mm Hg were 62% and 80%, respectively, and for 24-hour ABP daytime systolic readings ≥ 135 mm Hg were 65% and 77%, respectively.

WHAT’S NEW

Monitoring home BP can be simplified

The researchers found that HBP monitoring correlates well with ABPM and that their method provides clinicians with a simple way (three of the past 10 measurements ≥ 135 mm Hg systolic) to use HBP readings to make clinical decisions regarding BP management.

CAVEATS

BP goals are hazy, patient education is required

Conflicting information and opinions remain regarding the ideal intensive and standard BP goals in different populations.10,11 Systolic BP goals in this study (≥ 130 mm Hg for overall 24-hour ABP and ≥ 135 mm Hg for 24-hour ABP daytime readings) are recommended by some experts but are not commonly recognized goals in the United States. This study found good correlation between HBP and ABPM at these goals, and it seems likely that this correlation could be extrapolated for similar BP goals.

Other limitations are that (1) The study focused only on systolic BP goals; (2) patients in the study adhered to precise instructions on BP monitoring; HBP monitoring requires significant patient education on the proper use of the equipment and the monitoring schedule; and (3) while end-organ complication outcomes showed numerical decreases in function, the clinical significance of these reductions for patients is unclear.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost, sizing of cuffs

The cost of HBP monitors ($40-$60) has decreased significantly over time, but the devices are not always covered by insurance and may be unobtainable for some people.

Additionally, patients should be counseled on how to determine the appropriate cuff size to ensure the accuracy of the measurements. The British Hypertension Society maintains a list of validated BP devices on its website: http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors.12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(10):719-722.

1. Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

2. Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, et al. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2014;32:509-517.

3. Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778-786.

4. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

5. Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Baguet JP, et al. Acceptability and tolerance of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the hypertensive patient. Blood Press Monit. 1996; 1:197-203.

6. Gaborieau V, Delarche N, Gosse P. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring versus self-measurement of blood pressure at home: correlation with target organ damage. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1919-1927.

7. Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, et al. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449-456.

8. Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary. A joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:1-9.

9. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:779-785.

10. The SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

11. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2016;352:i717.

12. British Hypertension Society. BP Monitors. http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors. Accessed June 27, 2016.

1. Sharman JE, Blizzard L, Kosmala W, et al. Pragmatic method using blood pressure diaries to assess blood pressure control. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:63-69.

2. Sebo P, Pechère-Bertschi A, Herrmann FR, et al. Blood pressure measurements are unreliable to diagnose hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2014;32:509-517.

3. Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778-786.

4. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-2572.

5. Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Baguet JP, et al. Acceptability and tolerance of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the hypertensive patient. Blood Press Monit. 1996; 1:197-203.

6. Gaborieau V, Delarche N, Gosse P. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring versus self-measurement of blood pressure at home: correlation with target organ damage. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1919-1927.

7. Ward AM, Takahashi O, Stevens R, et al. Home measurement of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:449-456.

8. Pickering TG, Miller NH, Ogedegbe G, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: executive summary. A joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52:1-9.

9. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:779-785.

10. The SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

11. Brunström M, Carlberg B. Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2016;352:i717.

12. British Hypertension Society. BP Monitors. http://bhsoc.org/bp-monitors/bp-monitors. Accessed June 27, 2016.