User login

Migraine is a headache disorder that often causes unilateral pain, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting. More than 70% of office visits for migraine are made to primary care physicians.1 Recent data suggest migraine may be caused primarily by neuronal dysfunction and only secondarily by vasodilation.2 Although there are numerous classes of drugs used for migraine prevention and treatment, their success has been limited by inadequate efficacy, tolerability, and patient adherence.3 The discovery of pro-inflammatory markers such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) has led to the development of new medications to prevent and treat migraine.4

Pathophysiology, Dx and triggers, indications for pharmacotherapy

Pathophysiology. A migraine is thought to be caused by cortical spreading depression (CSD), a depolarization of glial and neuronal cell membranes.5

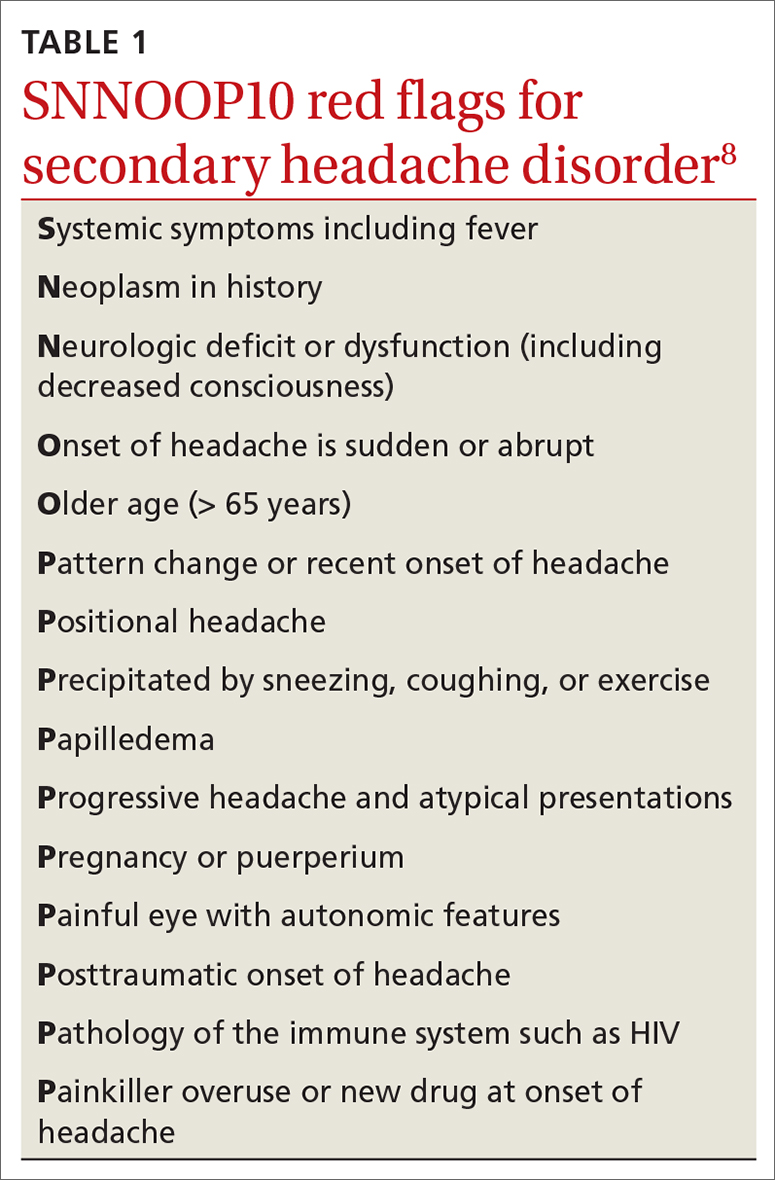

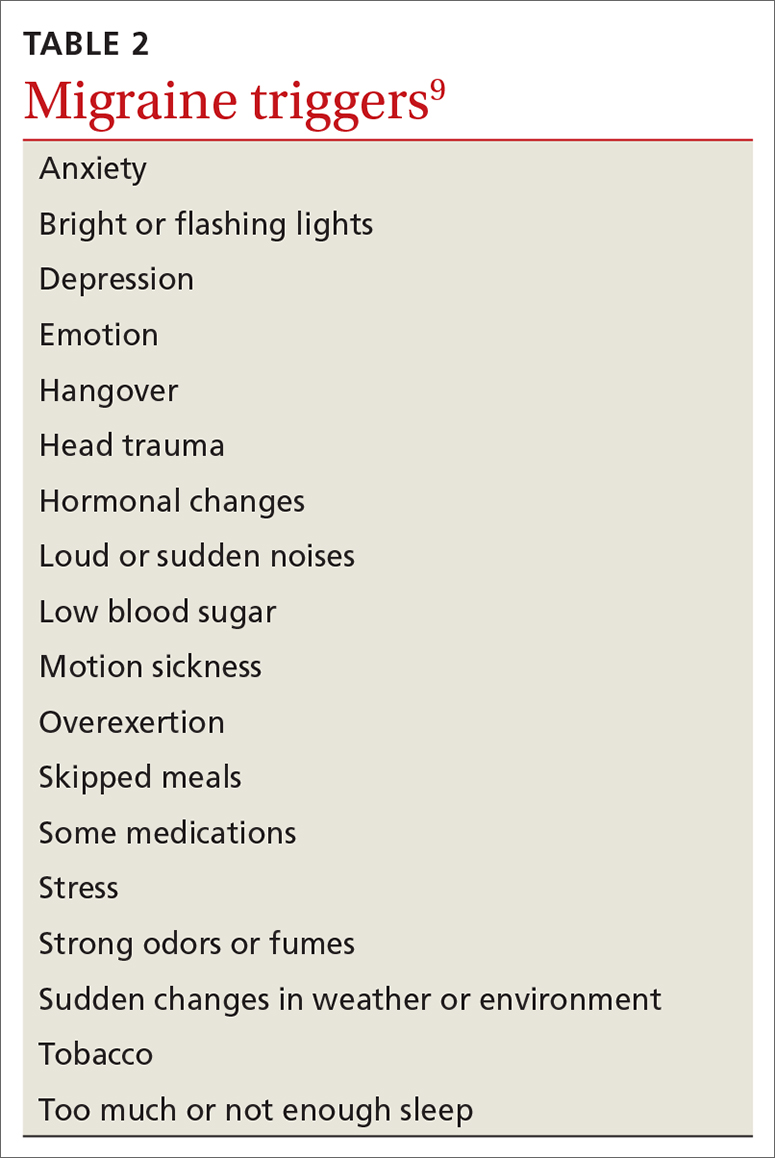

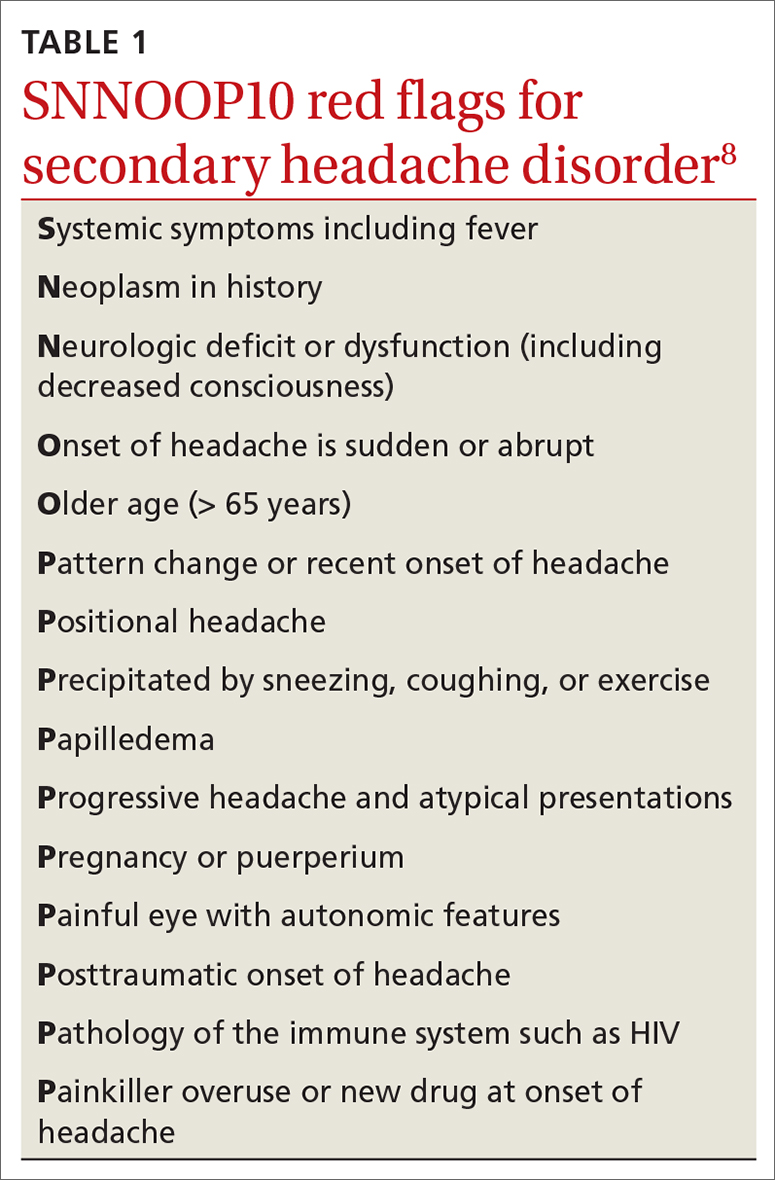

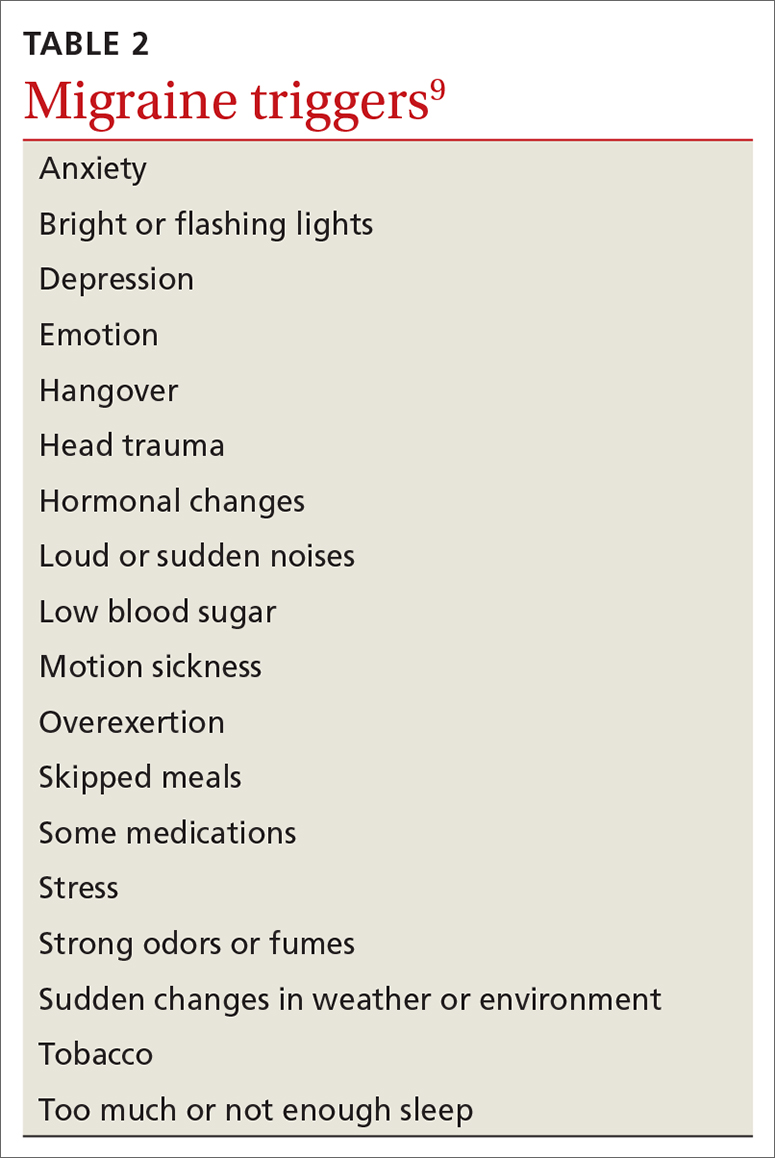

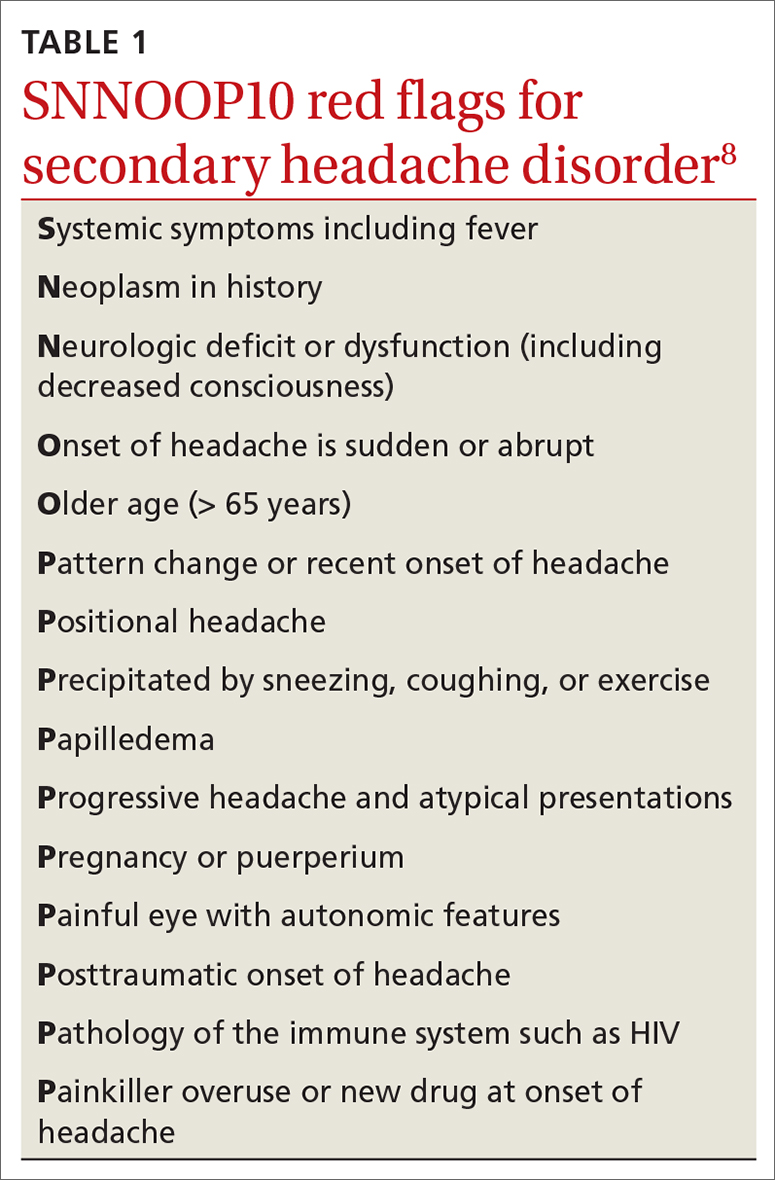

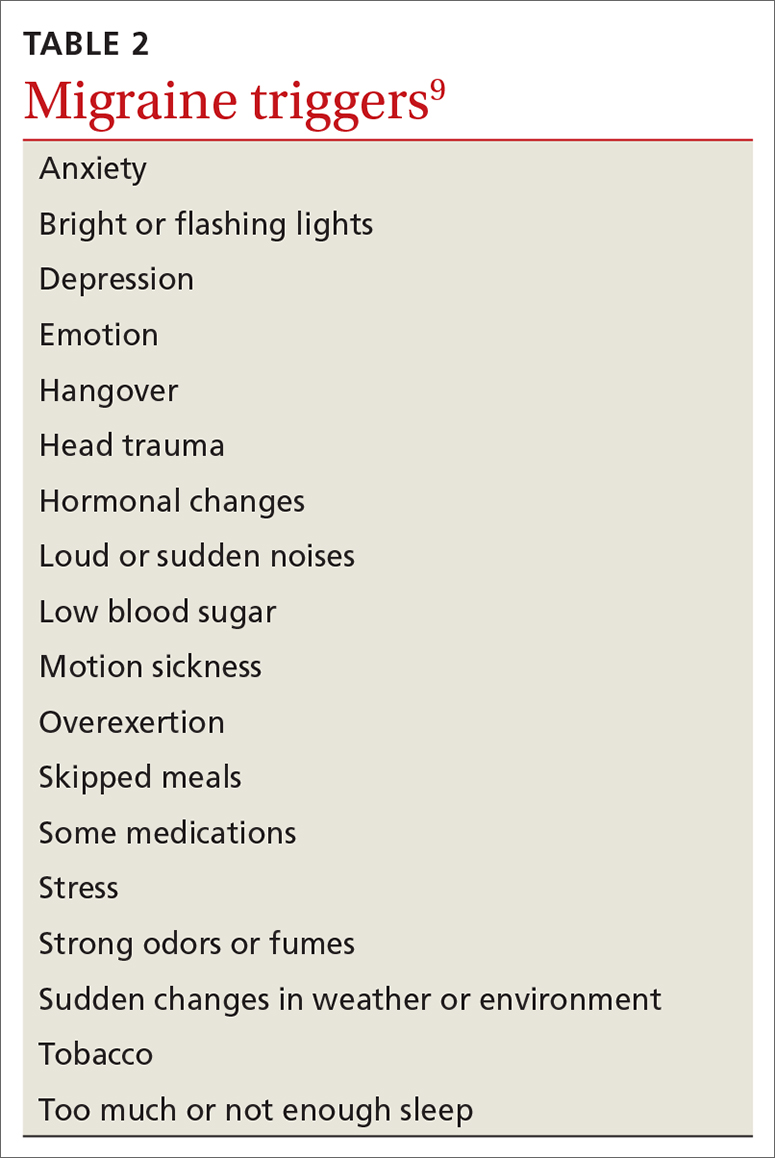

Dx and triggers. In 2018, the International Headache Society revised its guidelines for the diagnosis of migraine.7 According to the 3rd edition of The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), the diagnosis of migraine is made when a patient has at least 5 headache attacks that last 4 to 72 hours and have at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) unilateral location, (2) pulsating quality, (3) moderate-to-severe pain intensity, and (4) aggravated by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity.7 The headache attacks also should have (1) associated nausea or vomiting or (2) photophobia and phonophobia.7 The presence of atypical signs or symptoms as indicated by the SNNOOP10 mnemonic raises concerns for secondary headaches and the need for further investigation into the cause of the headache (TABLE 1).8 It is not possible to detect every secondary headache with standard neuroimaging, but the SNNOOP10 red flags can help determine when imaging may be indicated.8 Potential triggers for migraine can be found in TABLE 2.9

Indications for pharmacotherapy. All patients receiving a diagnosis of migraine should be offered acute pharmacologic treatment. Consider preventive therapy anytime there are ≥ 4 headache days per month, debilitating attacks despite acute therapy, overuse of acute medication (> 2 d/wk), difficulty tolerating acute medication, patient preference, or presence of certain migraine subtypes.7,10

Acute treatments

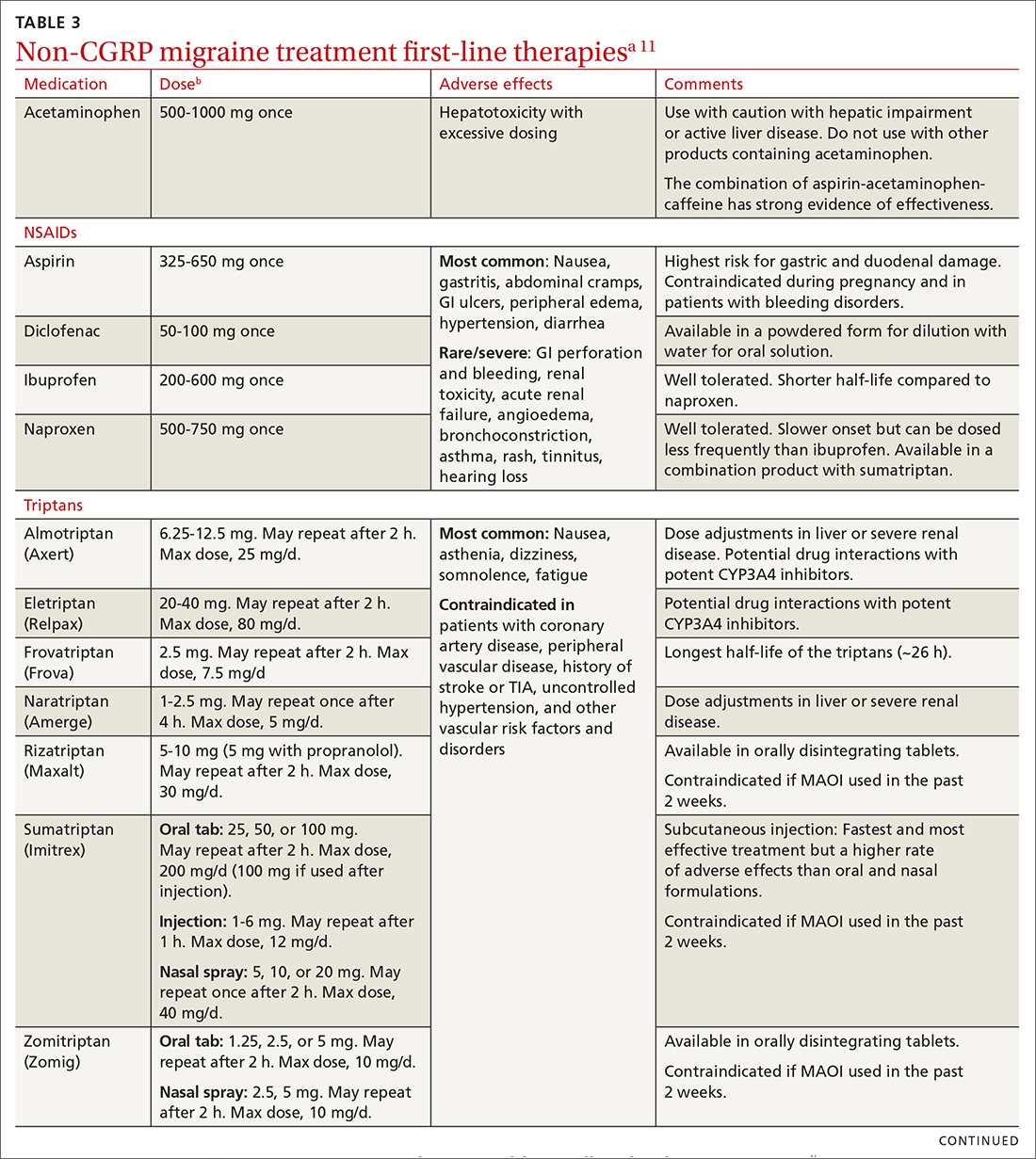

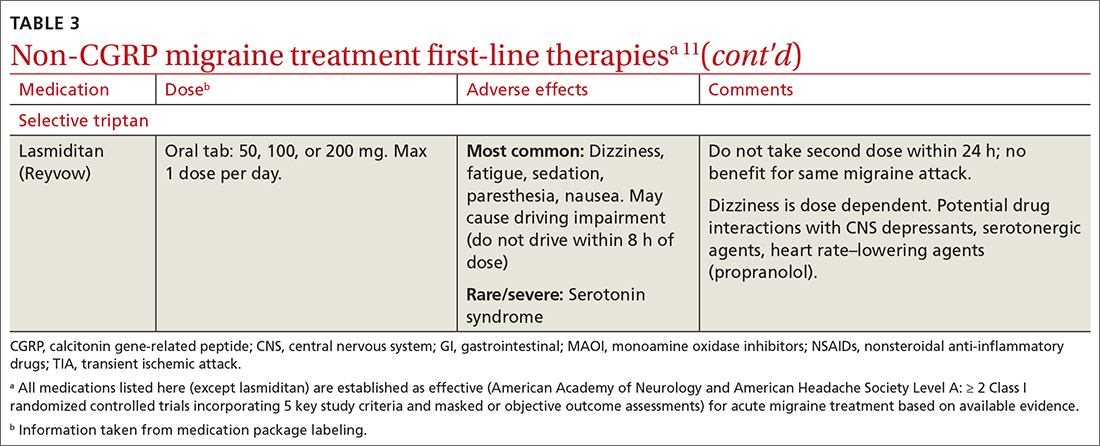

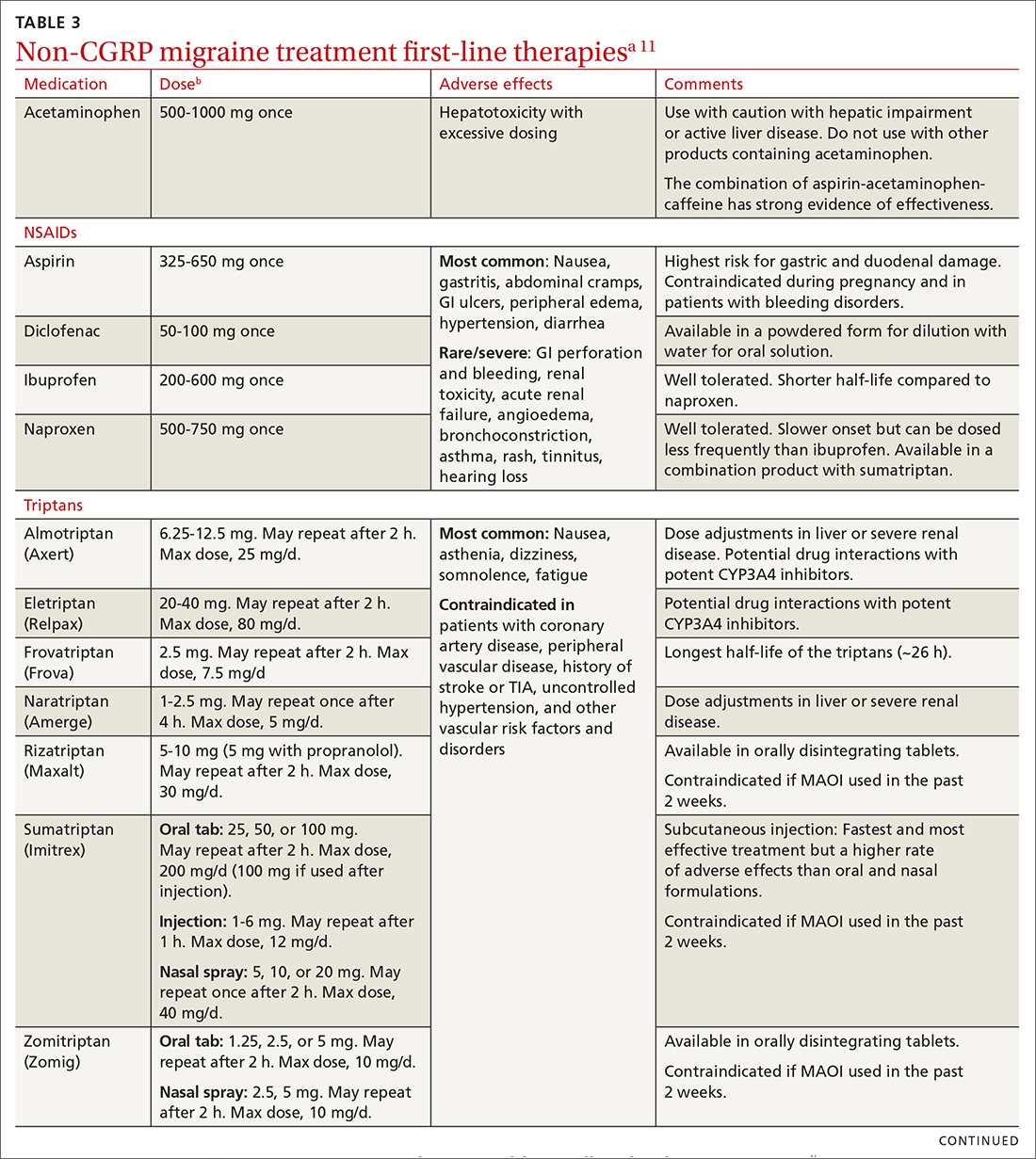

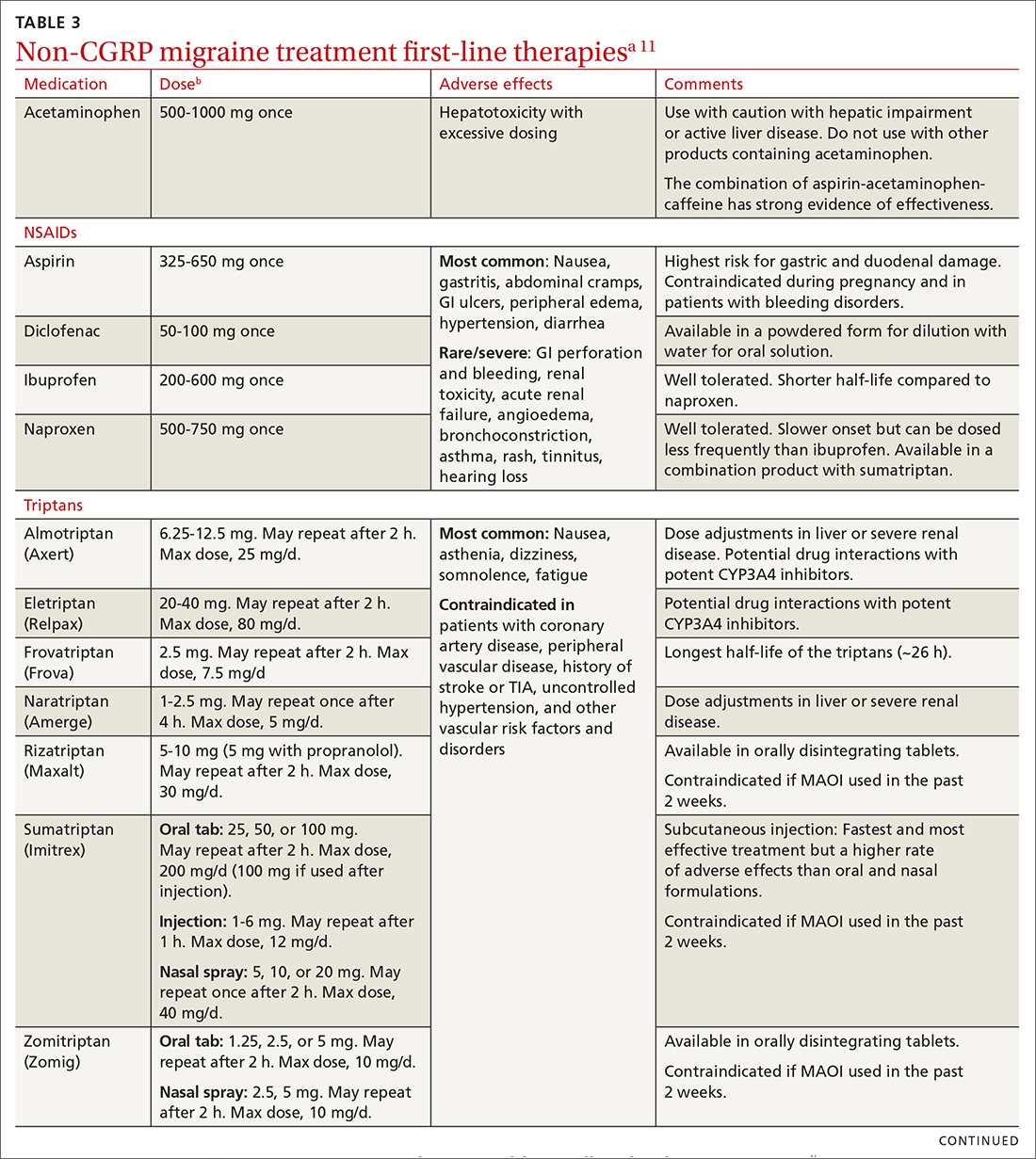

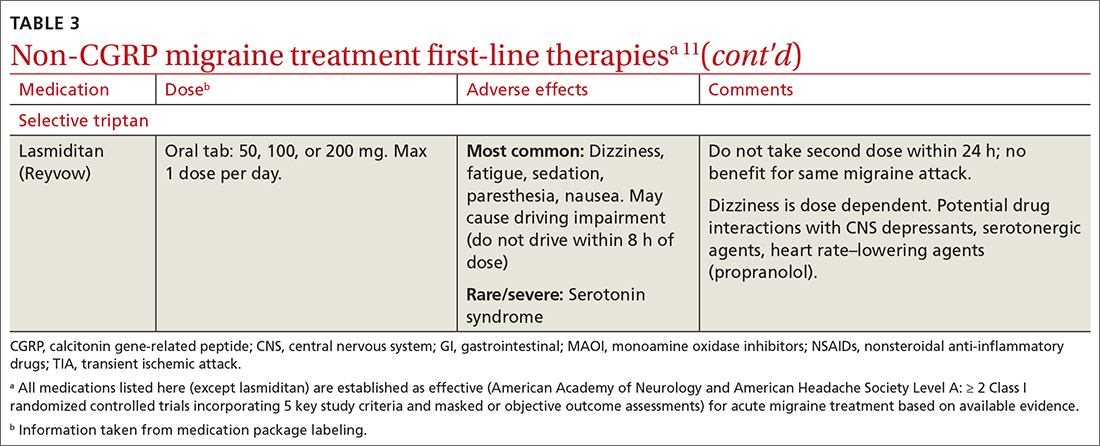

Abortive therapies for migraine include analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen, and ergot alkaloids, triptans, or small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants). Prompt administration increases the chance of success with acute therapy. Medications with the highest levels of efficacy based on the 2015 guidelines from the American Headache Society (AHS) are given in TABLE 3.11 Lasmiditan (Reyvow) is not included in the 2015 guidelines, as it was approved after publication of the guidelines.

Non-CGRP first-line therapies

NSAIDs and acetaminophen. NSAIDs such as aspirin, diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen have a high level of evidence to support their use as first-line treatments for mild-to-moderate migraine attacks. Trials consistently demonstrate their superiority to placebo in headache relief and complete pain relief at 2 hours. There is no recommendation for selecting one NSAID over another; however, consider their frequency of dosing and adverse effect profiles. The number needed to treat for complete pain relief at 2 hours ranges from 7 to 10 for most NSAIDs.11,12 In some placebo-controlled studies, acetaminophen was less effective than NSAIDs, but was safer because it did not cause gastric irritation or antiplatelet effects.12

Triptans inhibit 5-HT1B/1D receptors. Consider formulation, route of administration, cost, and pharmacokinetics when selecting a triptan. Patients who do not respond well to one triptan may respond favorably to another. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of the 7 available agents found that triptans at standard doses provided pain relief within 2 hours in 42% to 76% of patients, and sustained freedom from pain for 2 hours in 18% to 50% of patients.13 Lasmiditan is a selective serotonin receptor (5-HT1F) agonist that lacks vasoconstrictor activity. This is an option for patients with relative contraindications to triptans due to cardiovascular risk factors.10

Continue to: Second-line therapies

Second-line therapies

Intranasal dihydroergotamine has a favorable adverse event profile and greater evidence for efficacy compared with ergotamine. Compared with triptans, intranasal dihydroergotamine has a high level of efficacy but causes more adverse effects.14 Severe nausea is common, and dihydroergotamine often is used in combination with an antiemetic drug. Dihydroergotamine should not be used within 24 hours of taking a triptan, and it is contraindicated for patients who have hypertension or ischemic heart disease or who are pregnant or breastfeeding. There is also the potential for adverse drug interactions.15

Antiemetics may be helpful for migraine associated with severe nausea or vomiting. The dopamine antagonists metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, and chlorpromazine have demonstrated benefit in randomized placebo-controlled trials.11 Ondansetron has not been studied extensively, but sometimes is used in clinical practice. Nonoral routes of administration may be useful in patients having trouble swallowing medications or in those experiencing significant nausea or vomiting early during migraine attacks.

Due to the high potential for abuse, opioids should not be used routinely for the treatment of migraine.12 There is no high-quality evidence supporting the efficacy of barbiturates (ie, butalbital-containing compounds) for acute migraine treatment.11 Moreover, use of these agents may increase the likelihood of progression from episodic to chronic migraine.16

Gepants for acute migraine treatment

Neuropeptide CGRP is released from trigeminal nerves and is a potent dilator of cerebral and dural vessels, playing a key role in regulating blood flow to the brain. Other roles of CGRP include the release of inflammatory agents from mast cells and the transmission of painful stimuli from intracranial vessels.17 The CGRP receptor or ligand can be targeted by small-molecule receptor antagonists for acute and preventive migraine treatment (and by monoclonal antibodies solely for prevention, discussed later). It has been theorized that gepants bind to CGRP receptors, resulting in decreased blood flow to the brain, inhibition of neurogenic inflammation, and reduced pain signaling.17 Unlike triptans and ergotamine derivatives, these novel treatments do not constrict blood vessels and may have a unique role in patients with contraindications to triptans.

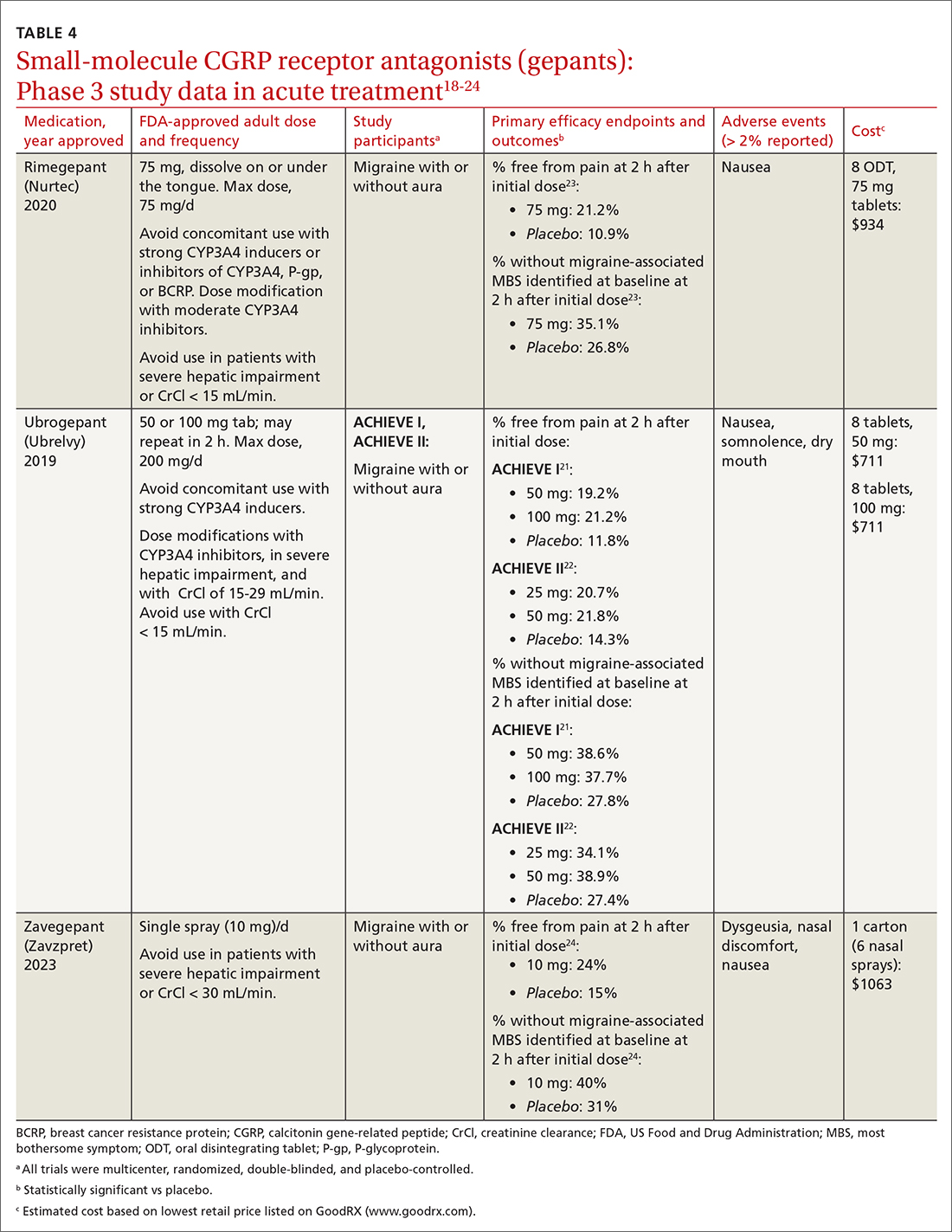

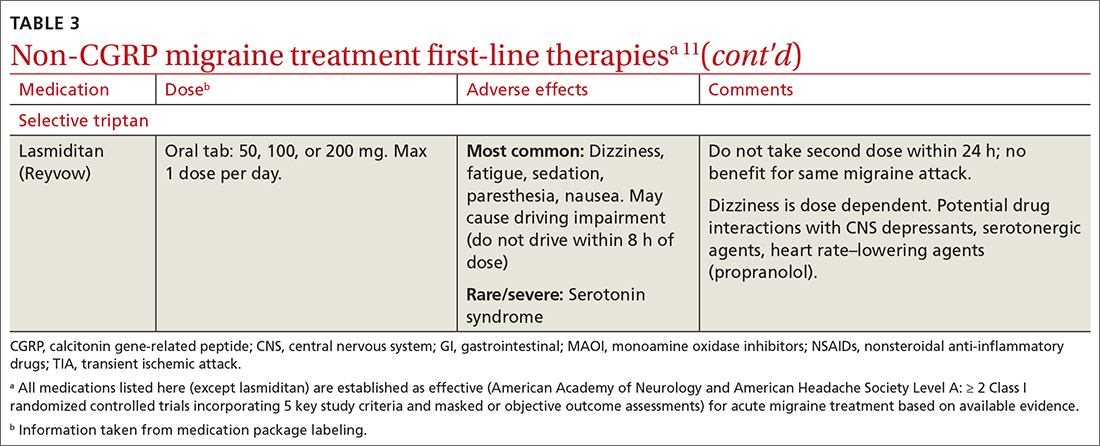

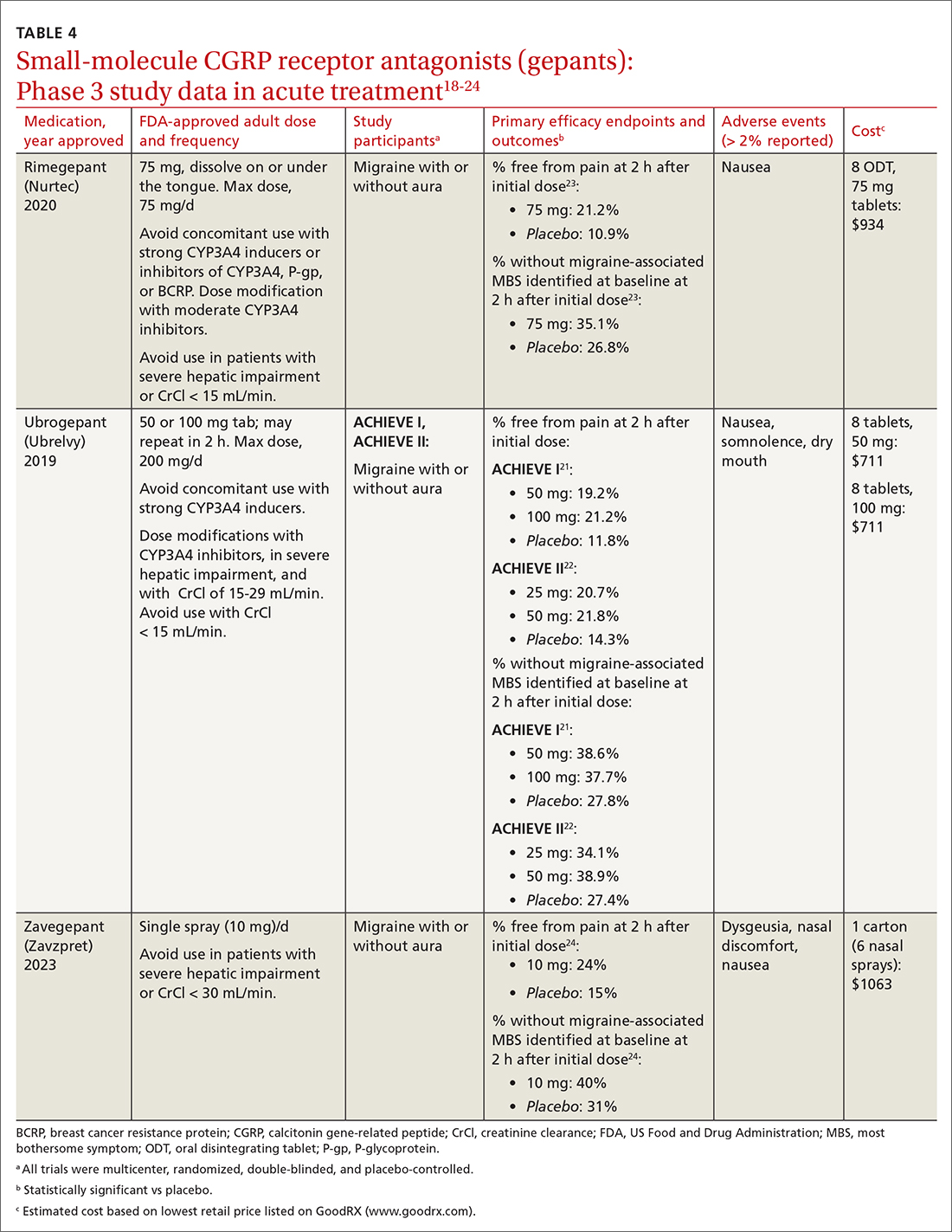

The 3 gepants approved for acute treatment—ubrogepant (Ubrelvy),18 rimegepant (Nurtec),19 and zavegepant (Zavzpret)20—were compared with placebo in clinical trials and were shown to increase the number of patients who were completely pain free at 2 hours, were free of the most bothersome associated symptom (photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea) at 2 hours, and remained pain free at 24 hours (TABLE 418-24).

Continue to: Ubrogrepant

Ubrogepant, in 2 Phase 3 trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) demonstrated effectiveness compared with placebo.21,22 The most common adverse effects reported were nausea and somnolence at very low rates. Pain-relief rates at 2 hours post dose (> 60% of participants) were higher than pain-free rates, and a significantly higher percentage (> 40%) of ubrogepant-treated participants reported ability to function normally on the Functional Disability Scale.25

Rimegepant was also superior to placebo (59% vs 43%) in pain relief at 2 hours post dose and other secondary endpoints.23 Rimegepant also has potential drug interactions

Zavegepant, approved in March 2023, is administered once daily as a 10-mg nasal spray. In its Phase 3 trial, zavegepant was significantly superior to placebo at 2 hours post dose in freedom from pain (24% v 15%), and in freedom from the most bothersome symptom (40% v 31%).24 Dosage modifications are not needed with mild-to-moderate renal or hepatic disease.20

Worth noting. The safety of using ubrogepant to treat more than 8 migraine episodes in a 30-day period has not been established. The safety of using more than 18 doses of zavegepant in a 30-day period also has not been established. With ubrogepant and rimegepant, there are dosing modifications for concomitant use with specific drugs (CYP3A4 inhibitors and inducers) due to potential interactions and in patients with hepatic or renal impairment.18,19

There are no trials comparing efficacy of CGRP antagonists to triptans. Recognizing that these newer medications would be costly, the AHS position statement released in 2019 recommends that gepants be considered for those with contraindications to triptans or for whom at least 2 oral triptans have failed (as determined by a validated patient outcome questionnaire).10 Step therapy with documentation of previous trials and therapy failures is often required by insurance companies prior to gepant coverage.

Continue to: Preventive therapies

Preventive therapies

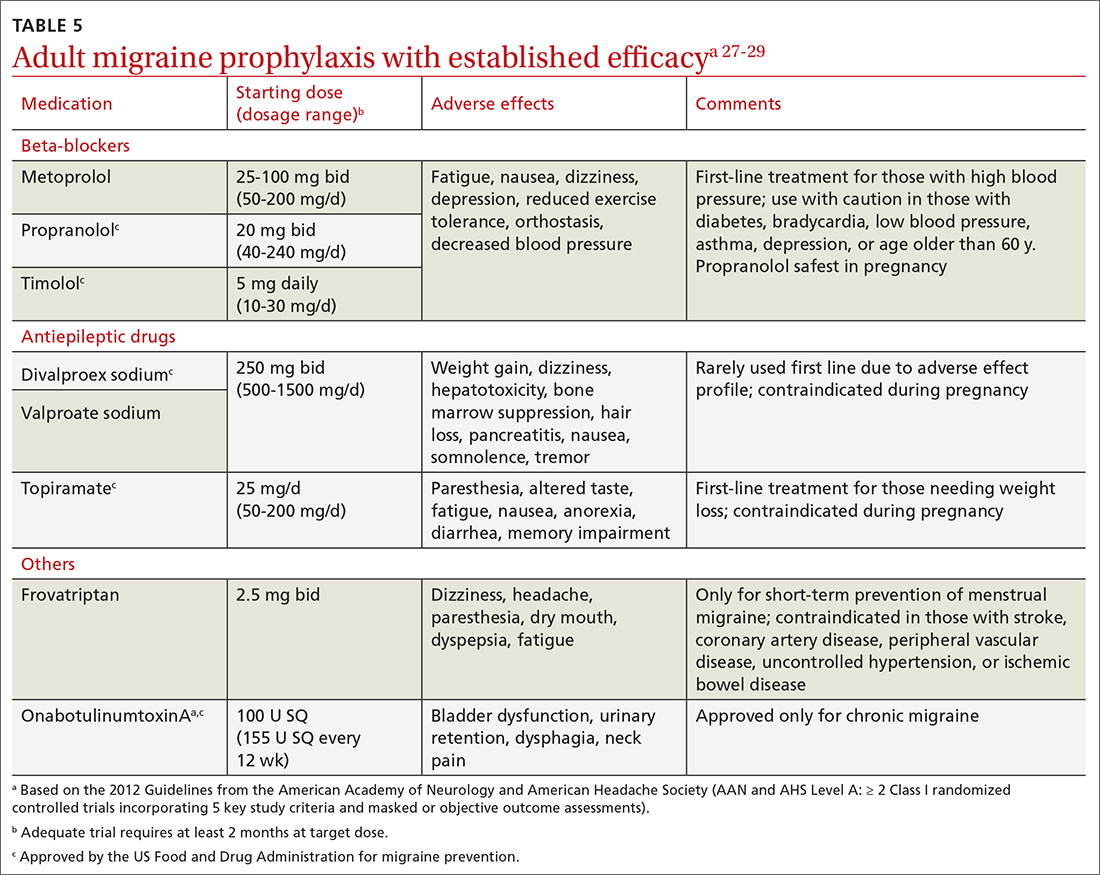

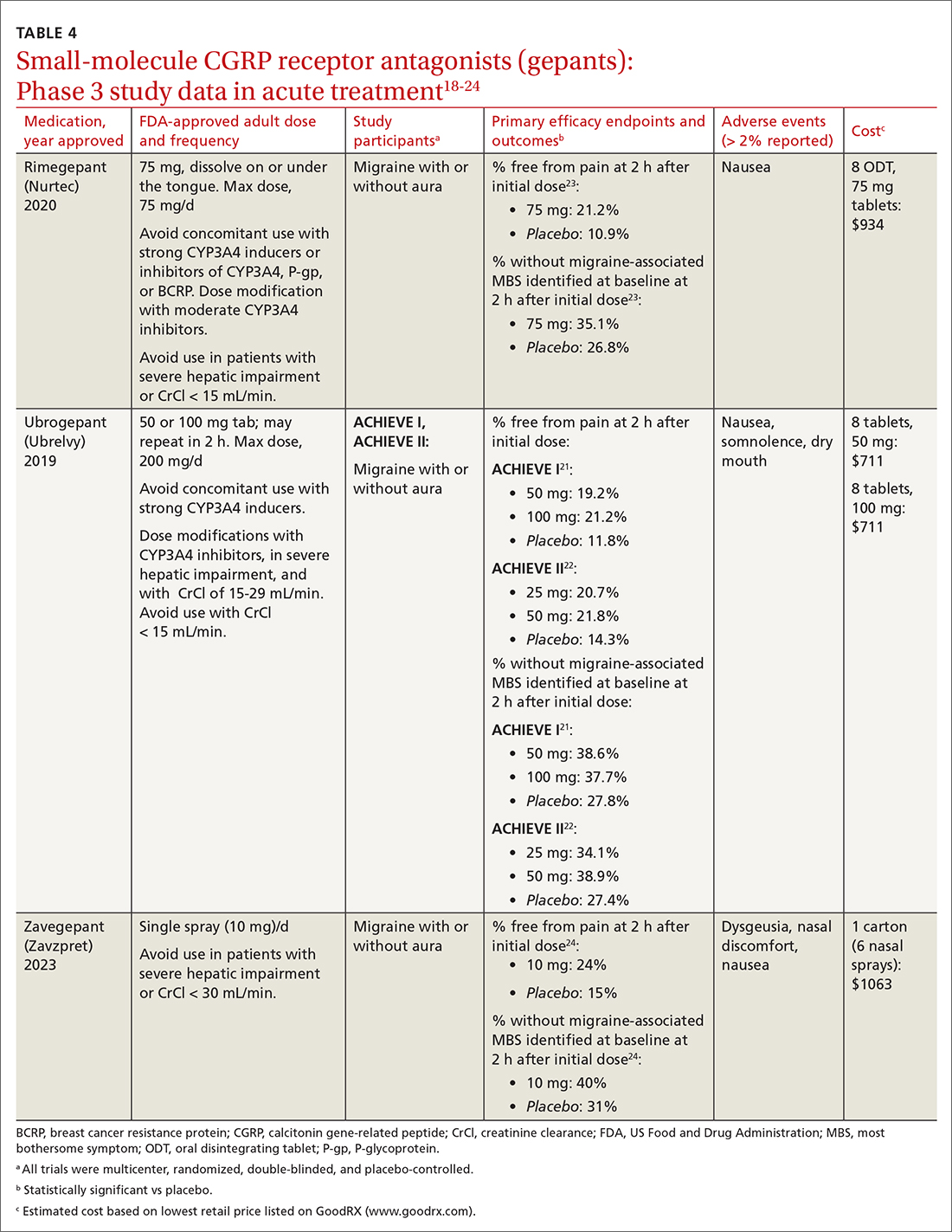

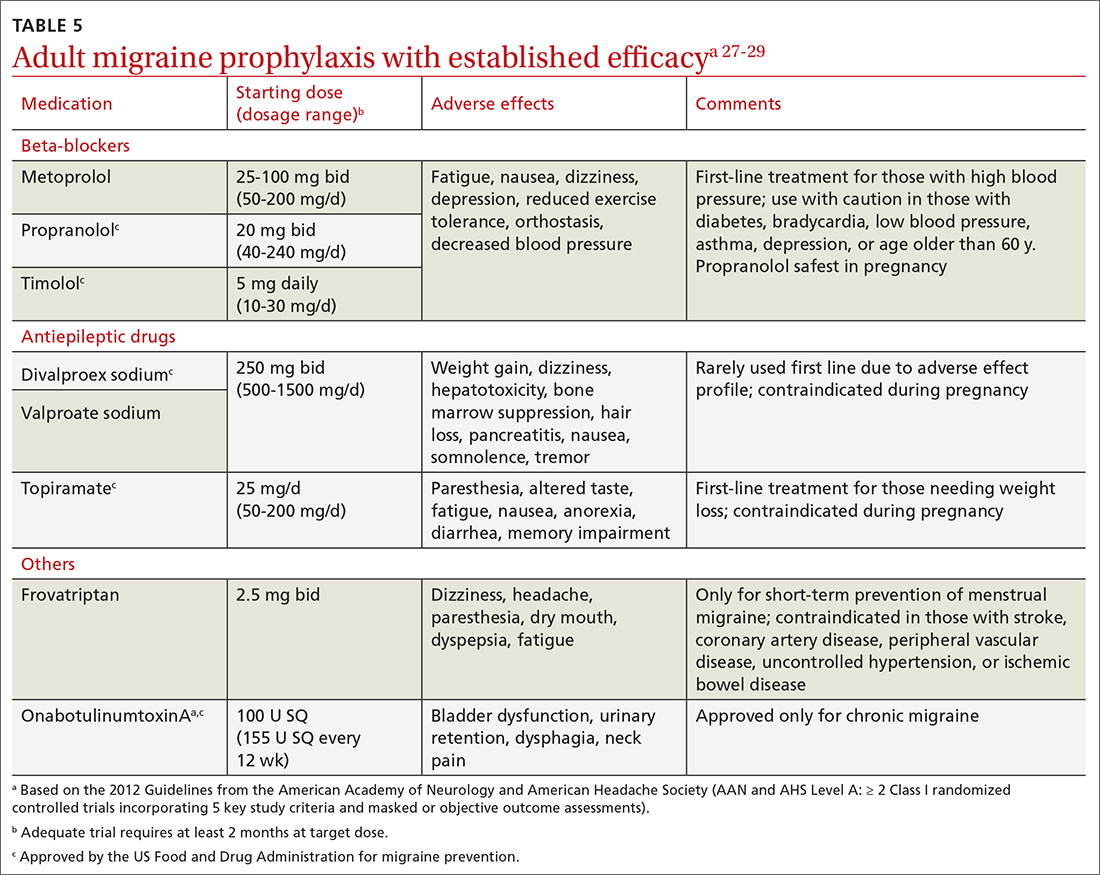

Preventive migraine therapies are used to reduce duration, frequency, and severity of attacks, the need for acute treatment, and overall headache disability.26 Medications typically are chosen based on efficacy, adverse effect profile, and patient comorbidities. Barriers to successful use include poor patient adherence and tolerability, the need for slow dose titration, and long-term use (minimum of 2 months) at maximum tolerated or minimum effective doses. Medications with established efficacy (Level Aa) based on the 2012 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the AHS are given in TABLE 5.27-29

Drugs having received the strongest level of evidence for migraine prevention are metoprolol, propranolol, timolol, topiramate, valproate sodium, divalproex sodium, and onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox), and frovatriptan for menstrual migraine prevention. Because these guidelines were last updated in 2012, they did not cover gepants (which will be discussed shortly). The AHS released a position statement in 2019 supporting the use of

CGRP-targeted prevention

Four anti-CGRP mAbs and 2 gepants have been approved for migraine prevention in the United States. Differences between products include targets (ligand vs receptor), antibody IgG subtype, bioavailability, route of administration, and frequency of administration.28 As noted in the Phase 3 studies (TABLE 619,30-47), these therapies are highly efficacious, safe, and tolerable.

Gepants. Rimegepant, discussed earlier for migraine treatment, is one of the CGRP receptor antagonists approved for prevention. The other is atogepant (Qulipta), approved only for prevention. Ubrogepant is not approved for prevention.

Anti-CGRP mAb is the only medication class specifically created for migraine prevention.10,26 As already noted, several efficacious non-CGRP treatment options are available for migraine prevention. However, higher doses of those agents, if needed,

Continue to: The targeted anti-CGRP approach...

The targeted anti-CGRP approach, which can be used by patients with liver or kidney disease, results in decreased toxicity and minimal drug interactions. Long half-lives allow for monthly or quarterly injections, possibly resulting in increased compliance.28 Dose titration is not needed, allowing for more rapid symptom management. The large molecular size of a mAb limits its transfer across the blood-brain barrier, making central nervous system adverse effects unlikely.28 Despite the compelling mAb pharmacologic properties, their use may be limited by a lack of long-term safety data and the need for parenteral administration. Although immunogenicity—the development of neutralizing antibodies—can limit long-term tolerability or efficacy of mAbs generally,26,28 anti-CGRP mAbs were engineered to minimally activate the immune system and have not been associated with immune suppression, opportunistic infections, malignancies, or decreased efficacy.28

A pooled meta-analysis including 4 trials (3166 patients) found that CGRP mAbs compared with placebo significantly improved patient response rates, defined as at least a 50% and 75% reduction in monthly headache/migraine days from baseline to Weeks 9 to 12.48 Another meta-analysis including 8 trials (2292 patients) found a significant reduction from baseline in monthly migraine days and monthly acute migraine medication consumption among patients taking CGRP mAbs compared with those taking placebo.49 Open-label extension studies have shown progressive and cumulative benefits in individuals who respond to anti-CGRP mAbs. Therefore, several treatment cycles may be necessary to determine overall efficacy of therapy.10,28

Cost initially can be a barrier. Insurance companies often require step therapy before agreeing to cover mAb therapy, which aligns with the 2019 AHS position statement.10

When combination treatment may be appropriate

Monotherapy is the usual approach to preventing migraine due to advantages of efficacy, simplified regimens, lower cost, and reduced adverse effects.51 However, if a patient does not benefit from monotherapy even after trying dose titrations as tolerated or switching therapies, trying complementary combination therapy is appropriate. Despite a shortage of clinical trials supporting the use of 2 or more preventive medications with different mechanisms of action, this strategy is used clinically.10 Consider combination therapy in those with refractory disease, partial responses, or intolerance to recommended doses.52 Articles reporting on case study reviews have rationalized the combined use of onabotulinumtoxinA and anti-CGRP mAbs, noting better migraine control.51,53 The 2019 AHS position statement recommends adding a mAb to an existing preventive treatment regimen with no other changes until mAb effectiveness is determined, as the risk for drug interactions on dual therapy is low.10 Safety and efficacy also have been demonstrated with the combination of preventive anti-CGRP mAbs and acute treatment with gepants as needed.54

CORRESPONDENCE

Emily Peterson, PharmD, BCACP, 3640 Middlebury Road, Iowa City, IA 52242; Emily-a-peterson@uiowa.edu

1. Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache. 2022;62:122-140. doi: 10.1111/head.14259

2. Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D. Migraine: multiple processes; complext pathophysiology. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6619-6629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015

3. Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, et al. CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies - successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:338-350. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0003-1

4. McGrath K, Rague A, Thesing C, et al. Migraine: expanding our Tx arsenal. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:10-14;16-24.

5. Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet. 2018;391:1315-1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30478-1

6. Agostoni EC, Barbanti P, Calabresi P, et al. Current and emerging evidence-based treatment options in chronic migraine: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:92. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1038-4

7. IHS. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202

8. Do TP, Remmers A, Schytz HW, et al. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Neurology. 2019;92:134-144. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006697

9. NIH. Migraine. Accessed July 30, 2023.

10. AHS. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1-18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456

11. Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55:3-20. doi: 10.1111/head.12499

12. Mayans L, Walling A. Acute migraine headache: treatment strategies. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:243-251.

13. Cameron C, Kelly S, Hsieh SC, et al. Triptans in the acute treatment of migraine: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Headache. 2015;55(suppl 4):221-235. doi: 10.1111/head.12601

14. Becker WJ. Acute migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21:953-972. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000192

15. Migranal (dihydroergotamine mesylate) Package insert. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America; 2019. Accessed June 17, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/020148Orig1s025lbl.pdf

16. Minen MT, Tanev K, Friedman BW. Evaluation and treatment of migraine in the emergency department: a review. Headache. 2014;54:1131-45. doi: 10.1111/head.12399

17. Durham PL. CGRP-receptor antagonists--a fresh approach to migraine therapy? N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1073-1075. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048016

18. Ubrelvy (ubrogepant). Package insert. Allergan, Inc.; 2019. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211765s000lbl.pdf

19. Nurtec ODT (rimegepant sulfate). Package insert. Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/212728s006lbl.pdf

20. Zavzpret (zavegepant). Package insert. Pfizer Labs.; 2023. Accessed July 15, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216386s000lbl.pdf

21. Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2230-2241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813049

22. Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1887-1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711

23. Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:737-745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31606-X

24. Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock DA, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine in the USA: a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:209-217. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00517-8

25. Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant, an acute treatment for migraine, improved patient-reported functional disability and satisfaction in 2 single-attack phase 3 randomized trials, ACHIEVE I and II. Headache. 2020;60:686-700. doi: 10.1111/head.13766

26. Burch R. Migraine and tension-type headache: diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:215-233. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.003

27. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20

28. Dodick DW. CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: evidence review and clinical implications. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:445-458. doi: 10.1177/ 0333102418821662

29. Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Becker WJ. Prophylaxis of migraine headache. CMAJ. 2010;182:E269-276. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081657

30. Vyepti (eptinezumab-jjmr). Package insert. Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals LLV; 2020. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761119s000lbl.pdf

31. Aimovig (erenumab-aooe). Package insert. Amgen Inc.; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761077s009lbl.pdf

32. Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm). Package insert. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; 2018. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761089s000lbl.pdf

33. Emgality (galcanezumab-gnlm). Package insert. Eli Lilly and Company; 2018. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761063s000lbl.pdf

34. Ashina M, Saper J, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia. 2020;40:241-254. doi: 10.1177/0333102420905132

35. Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Smith J, et al. Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine: PROMISE-2. Neurology. 2020;94:e1365-e1377. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009169

36. Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, et al. ARISE: a phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1026-1037. doi: 10.1177/0333102418759786

37. Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2123-2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705848

38. Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet. 2018;392:2280-2287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32534-0

39. Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, et al. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:2113-2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709038

40. Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, et al. Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1999-2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.4853

41. Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, et al. Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1080-1088. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1212

42. Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, et al. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1442-1454. doi: 10.1177/0333102418779543

43. Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, et al. Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology. 2018;91:e2211-e2221. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006640

44. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Leone M, at al. Trial of galcanezumab in prevention of episodic cluster headache. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:132-141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813440

45. Croop R, Lipton RB, Kudrow D, et al. Oral rimegepant for preventive treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:51-60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32544-7

46. Ailani J, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, et al. Atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:695-706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035908

47. Qulipta (atogepant). Package insert. AbbVie; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215206Orig1s000lbl.pdf

48. Han L, Liu Y, Xiong H, et al. CGRP monoclonal antibody for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: an update of meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01215. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1215

49. Zhu Y, Liu Y, Zhao J, et al. The efficacy and safety of calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody for episodic migraine: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2018;39:2097-2106. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3547-3

50. Szperka CL, VanderPluym J, Orr SL, et al. Recommendations on the use of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in children and adolescents. Headache. 2018;58:1658-1669. doi: 10.1111/head.13414

51. Pellesi L, Do TP, Ashina H, et al. Dual therapy with anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies and botulinum toxin for migraine prevention: is there a rationale? Headache. 2020;60:1056-1065. doi: 10.1111/head.13843

52. D’Antona L, Matharu M. Identifying and managing refractory migraine: barriers and opportunities? J Headache Pain. 2019;20:89. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1040-x

53. Cohen F, Armand C, Lipton RB, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of calcitonin gene-related peptide targeted monoclonal antibody medications as add-on therapy to onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine. Pain Med. 2021;1857-1863. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab093

54. Berman G, Croop R, Kudrow D, et al. Safety of rimegepant, an oral CGRP receptor antagonist, plus CGRP monoclonal antibodies for migraine. Headache. 2020;60:1734-1742. doi: 10.1111/head.13930

Migraine is a headache disorder that often causes unilateral pain, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting. More than 70% of office visits for migraine are made to primary care physicians.1 Recent data suggest migraine may be caused primarily by neuronal dysfunction and only secondarily by vasodilation.2 Although there are numerous classes of drugs used for migraine prevention and treatment, their success has been limited by inadequate efficacy, tolerability, and patient adherence.3 The discovery of pro-inflammatory markers such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) has led to the development of new medications to prevent and treat migraine.4

Pathophysiology, Dx and triggers, indications for pharmacotherapy

Pathophysiology. A migraine is thought to be caused by cortical spreading depression (CSD), a depolarization of glial and neuronal cell membranes.5

Dx and triggers. In 2018, the International Headache Society revised its guidelines for the diagnosis of migraine.7 According to the 3rd edition of The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), the diagnosis of migraine is made when a patient has at least 5 headache attacks that last 4 to 72 hours and have at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) unilateral location, (2) pulsating quality, (3) moderate-to-severe pain intensity, and (4) aggravated by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity.7 The headache attacks also should have (1) associated nausea or vomiting or (2) photophobia and phonophobia.7 The presence of atypical signs or symptoms as indicated by the SNNOOP10 mnemonic raises concerns for secondary headaches and the need for further investigation into the cause of the headache (TABLE 1).8 It is not possible to detect every secondary headache with standard neuroimaging, but the SNNOOP10 red flags can help determine when imaging may be indicated.8 Potential triggers for migraine can be found in TABLE 2.9

Indications for pharmacotherapy. All patients receiving a diagnosis of migraine should be offered acute pharmacologic treatment. Consider preventive therapy anytime there are ≥ 4 headache days per month, debilitating attacks despite acute therapy, overuse of acute medication (> 2 d/wk), difficulty tolerating acute medication, patient preference, or presence of certain migraine subtypes.7,10

Acute treatments

Abortive therapies for migraine include analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen, and ergot alkaloids, triptans, or small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants). Prompt administration increases the chance of success with acute therapy. Medications with the highest levels of efficacy based on the 2015 guidelines from the American Headache Society (AHS) are given in TABLE 3.11 Lasmiditan (Reyvow) is not included in the 2015 guidelines, as it was approved after publication of the guidelines.

Non-CGRP first-line therapies

NSAIDs and acetaminophen. NSAIDs such as aspirin, diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen have a high level of evidence to support their use as first-line treatments for mild-to-moderate migraine attacks. Trials consistently demonstrate their superiority to placebo in headache relief and complete pain relief at 2 hours. There is no recommendation for selecting one NSAID over another; however, consider their frequency of dosing and adverse effect profiles. The number needed to treat for complete pain relief at 2 hours ranges from 7 to 10 for most NSAIDs.11,12 In some placebo-controlled studies, acetaminophen was less effective than NSAIDs, but was safer because it did not cause gastric irritation or antiplatelet effects.12

Triptans inhibit 5-HT1B/1D receptors. Consider formulation, route of administration, cost, and pharmacokinetics when selecting a triptan. Patients who do not respond well to one triptan may respond favorably to another. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of the 7 available agents found that triptans at standard doses provided pain relief within 2 hours in 42% to 76% of patients, and sustained freedom from pain for 2 hours in 18% to 50% of patients.13 Lasmiditan is a selective serotonin receptor (5-HT1F) agonist that lacks vasoconstrictor activity. This is an option for patients with relative contraindications to triptans due to cardiovascular risk factors.10

Continue to: Second-line therapies

Second-line therapies

Intranasal dihydroergotamine has a favorable adverse event profile and greater evidence for efficacy compared with ergotamine. Compared with triptans, intranasal dihydroergotamine has a high level of efficacy but causes more adverse effects.14 Severe nausea is common, and dihydroergotamine often is used in combination with an antiemetic drug. Dihydroergotamine should not be used within 24 hours of taking a triptan, and it is contraindicated for patients who have hypertension or ischemic heart disease or who are pregnant or breastfeeding. There is also the potential for adverse drug interactions.15

Antiemetics may be helpful for migraine associated with severe nausea or vomiting. The dopamine antagonists metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, and chlorpromazine have demonstrated benefit in randomized placebo-controlled trials.11 Ondansetron has not been studied extensively, but sometimes is used in clinical practice. Nonoral routes of administration may be useful in patients having trouble swallowing medications or in those experiencing significant nausea or vomiting early during migraine attacks.

Due to the high potential for abuse, opioids should not be used routinely for the treatment of migraine.12 There is no high-quality evidence supporting the efficacy of barbiturates (ie, butalbital-containing compounds) for acute migraine treatment.11 Moreover, use of these agents may increase the likelihood of progression from episodic to chronic migraine.16

Gepants for acute migraine treatment

Neuropeptide CGRP is released from trigeminal nerves and is a potent dilator of cerebral and dural vessels, playing a key role in regulating blood flow to the brain. Other roles of CGRP include the release of inflammatory agents from mast cells and the transmission of painful stimuli from intracranial vessels.17 The CGRP receptor or ligand can be targeted by small-molecule receptor antagonists for acute and preventive migraine treatment (and by monoclonal antibodies solely for prevention, discussed later). It has been theorized that gepants bind to CGRP receptors, resulting in decreased blood flow to the brain, inhibition of neurogenic inflammation, and reduced pain signaling.17 Unlike triptans and ergotamine derivatives, these novel treatments do not constrict blood vessels and may have a unique role in patients with contraindications to triptans.

The 3 gepants approved for acute treatment—ubrogepant (Ubrelvy),18 rimegepant (Nurtec),19 and zavegepant (Zavzpret)20—were compared with placebo in clinical trials and were shown to increase the number of patients who were completely pain free at 2 hours, were free of the most bothersome associated symptom (photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea) at 2 hours, and remained pain free at 24 hours (TABLE 418-24).

Continue to: Ubrogrepant

Ubrogepant, in 2 Phase 3 trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) demonstrated effectiveness compared with placebo.21,22 The most common adverse effects reported were nausea and somnolence at very low rates. Pain-relief rates at 2 hours post dose (> 60% of participants) were higher than pain-free rates, and a significantly higher percentage (> 40%) of ubrogepant-treated participants reported ability to function normally on the Functional Disability Scale.25

Rimegepant was also superior to placebo (59% vs 43%) in pain relief at 2 hours post dose and other secondary endpoints.23 Rimegepant also has potential drug interactions

Zavegepant, approved in March 2023, is administered once daily as a 10-mg nasal spray. In its Phase 3 trial, zavegepant was significantly superior to placebo at 2 hours post dose in freedom from pain (24% v 15%), and in freedom from the most bothersome symptom (40% v 31%).24 Dosage modifications are not needed with mild-to-moderate renal or hepatic disease.20

Worth noting. The safety of using ubrogepant to treat more than 8 migraine episodes in a 30-day period has not been established. The safety of using more than 18 doses of zavegepant in a 30-day period also has not been established. With ubrogepant and rimegepant, there are dosing modifications for concomitant use with specific drugs (CYP3A4 inhibitors and inducers) due to potential interactions and in patients with hepatic or renal impairment.18,19

There are no trials comparing efficacy of CGRP antagonists to triptans. Recognizing that these newer medications would be costly, the AHS position statement released in 2019 recommends that gepants be considered for those with contraindications to triptans or for whom at least 2 oral triptans have failed (as determined by a validated patient outcome questionnaire).10 Step therapy with documentation of previous trials and therapy failures is often required by insurance companies prior to gepant coverage.

Continue to: Preventive therapies

Preventive therapies

Preventive migraine therapies are used to reduce duration, frequency, and severity of attacks, the need for acute treatment, and overall headache disability.26 Medications typically are chosen based on efficacy, adverse effect profile, and patient comorbidities. Barriers to successful use include poor patient adherence and tolerability, the need for slow dose titration, and long-term use (minimum of 2 months) at maximum tolerated or minimum effective doses. Medications with established efficacy (Level Aa) based on the 2012 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the AHS are given in TABLE 5.27-29

Drugs having received the strongest level of evidence for migraine prevention are metoprolol, propranolol, timolol, topiramate, valproate sodium, divalproex sodium, and onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox), and frovatriptan for menstrual migraine prevention. Because these guidelines were last updated in 2012, they did not cover gepants (which will be discussed shortly). The AHS released a position statement in 2019 supporting the use of

CGRP-targeted prevention

Four anti-CGRP mAbs and 2 gepants have been approved for migraine prevention in the United States. Differences between products include targets (ligand vs receptor), antibody IgG subtype, bioavailability, route of administration, and frequency of administration.28 As noted in the Phase 3 studies (TABLE 619,30-47), these therapies are highly efficacious, safe, and tolerable.

Gepants. Rimegepant, discussed earlier for migraine treatment, is one of the CGRP receptor antagonists approved for prevention. The other is atogepant (Qulipta), approved only for prevention. Ubrogepant is not approved for prevention.

Anti-CGRP mAb is the only medication class specifically created for migraine prevention.10,26 As already noted, several efficacious non-CGRP treatment options are available for migraine prevention. However, higher doses of those agents, if needed,

Continue to: The targeted anti-CGRP approach...

The targeted anti-CGRP approach, which can be used by patients with liver or kidney disease, results in decreased toxicity and minimal drug interactions. Long half-lives allow for monthly or quarterly injections, possibly resulting in increased compliance.28 Dose titration is not needed, allowing for more rapid symptom management. The large molecular size of a mAb limits its transfer across the blood-brain barrier, making central nervous system adverse effects unlikely.28 Despite the compelling mAb pharmacologic properties, their use may be limited by a lack of long-term safety data and the need for parenteral administration. Although immunogenicity—the development of neutralizing antibodies—can limit long-term tolerability or efficacy of mAbs generally,26,28 anti-CGRP mAbs were engineered to minimally activate the immune system and have not been associated with immune suppression, opportunistic infections, malignancies, or decreased efficacy.28

A pooled meta-analysis including 4 trials (3166 patients) found that CGRP mAbs compared with placebo significantly improved patient response rates, defined as at least a 50% and 75% reduction in monthly headache/migraine days from baseline to Weeks 9 to 12.48 Another meta-analysis including 8 trials (2292 patients) found a significant reduction from baseline in monthly migraine days and monthly acute migraine medication consumption among patients taking CGRP mAbs compared with those taking placebo.49 Open-label extension studies have shown progressive and cumulative benefits in individuals who respond to anti-CGRP mAbs. Therefore, several treatment cycles may be necessary to determine overall efficacy of therapy.10,28

Cost initially can be a barrier. Insurance companies often require step therapy before agreeing to cover mAb therapy, which aligns with the 2019 AHS position statement.10

When combination treatment may be appropriate

Monotherapy is the usual approach to preventing migraine due to advantages of efficacy, simplified regimens, lower cost, and reduced adverse effects.51 However, if a patient does not benefit from monotherapy even after trying dose titrations as tolerated or switching therapies, trying complementary combination therapy is appropriate. Despite a shortage of clinical trials supporting the use of 2 or more preventive medications with different mechanisms of action, this strategy is used clinically.10 Consider combination therapy in those with refractory disease, partial responses, or intolerance to recommended doses.52 Articles reporting on case study reviews have rationalized the combined use of onabotulinumtoxinA and anti-CGRP mAbs, noting better migraine control.51,53 The 2019 AHS position statement recommends adding a mAb to an existing preventive treatment regimen with no other changes until mAb effectiveness is determined, as the risk for drug interactions on dual therapy is low.10 Safety and efficacy also have been demonstrated with the combination of preventive anti-CGRP mAbs and acute treatment with gepants as needed.54

CORRESPONDENCE

Emily Peterson, PharmD, BCACP, 3640 Middlebury Road, Iowa City, IA 52242; Emily-a-peterson@uiowa.edu

Migraine is a headache disorder that often causes unilateral pain, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting. More than 70% of office visits for migraine are made to primary care physicians.1 Recent data suggest migraine may be caused primarily by neuronal dysfunction and only secondarily by vasodilation.2 Although there are numerous classes of drugs used for migraine prevention and treatment, their success has been limited by inadequate efficacy, tolerability, and patient adherence.3 The discovery of pro-inflammatory markers such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) has led to the development of new medications to prevent and treat migraine.4

Pathophysiology, Dx and triggers, indications for pharmacotherapy

Pathophysiology. A migraine is thought to be caused by cortical spreading depression (CSD), a depolarization of glial and neuronal cell membranes.5

Dx and triggers. In 2018, the International Headache Society revised its guidelines for the diagnosis of migraine.7 According to the 3rd edition of The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), the diagnosis of migraine is made when a patient has at least 5 headache attacks that last 4 to 72 hours and have at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) unilateral location, (2) pulsating quality, (3) moderate-to-severe pain intensity, and (4) aggravated by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity.7 The headache attacks also should have (1) associated nausea or vomiting or (2) photophobia and phonophobia.7 The presence of atypical signs or symptoms as indicated by the SNNOOP10 mnemonic raises concerns for secondary headaches and the need for further investigation into the cause of the headache (TABLE 1).8 It is not possible to detect every secondary headache with standard neuroimaging, but the SNNOOP10 red flags can help determine when imaging may be indicated.8 Potential triggers for migraine can be found in TABLE 2.9

Indications for pharmacotherapy. All patients receiving a diagnosis of migraine should be offered acute pharmacologic treatment. Consider preventive therapy anytime there are ≥ 4 headache days per month, debilitating attacks despite acute therapy, overuse of acute medication (> 2 d/wk), difficulty tolerating acute medication, patient preference, or presence of certain migraine subtypes.7,10

Acute treatments

Abortive therapies for migraine include analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen, and ergot alkaloids, triptans, or small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants). Prompt administration increases the chance of success with acute therapy. Medications with the highest levels of efficacy based on the 2015 guidelines from the American Headache Society (AHS) are given in TABLE 3.11 Lasmiditan (Reyvow) is not included in the 2015 guidelines, as it was approved after publication of the guidelines.

Non-CGRP first-line therapies

NSAIDs and acetaminophen. NSAIDs such as aspirin, diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen have a high level of evidence to support their use as first-line treatments for mild-to-moderate migraine attacks. Trials consistently demonstrate their superiority to placebo in headache relief and complete pain relief at 2 hours. There is no recommendation for selecting one NSAID over another; however, consider their frequency of dosing and adverse effect profiles. The number needed to treat for complete pain relief at 2 hours ranges from 7 to 10 for most NSAIDs.11,12 In some placebo-controlled studies, acetaminophen was less effective than NSAIDs, but was safer because it did not cause gastric irritation or antiplatelet effects.12

Triptans inhibit 5-HT1B/1D receptors. Consider formulation, route of administration, cost, and pharmacokinetics when selecting a triptan. Patients who do not respond well to one triptan may respond favorably to another. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of the 7 available agents found that triptans at standard doses provided pain relief within 2 hours in 42% to 76% of patients, and sustained freedom from pain for 2 hours in 18% to 50% of patients.13 Lasmiditan is a selective serotonin receptor (5-HT1F) agonist that lacks vasoconstrictor activity. This is an option for patients with relative contraindications to triptans due to cardiovascular risk factors.10

Continue to: Second-line therapies

Second-line therapies

Intranasal dihydroergotamine has a favorable adverse event profile and greater evidence for efficacy compared with ergotamine. Compared with triptans, intranasal dihydroergotamine has a high level of efficacy but causes more adverse effects.14 Severe nausea is common, and dihydroergotamine often is used in combination with an antiemetic drug. Dihydroergotamine should not be used within 24 hours of taking a triptan, and it is contraindicated for patients who have hypertension or ischemic heart disease or who are pregnant or breastfeeding. There is also the potential for adverse drug interactions.15

Antiemetics may be helpful for migraine associated with severe nausea or vomiting. The dopamine antagonists metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, and chlorpromazine have demonstrated benefit in randomized placebo-controlled trials.11 Ondansetron has not been studied extensively, but sometimes is used in clinical practice. Nonoral routes of administration may be useful in patients having trouble swallowing medications or in those experiencing significant nausea or vomiting early during migraine attacks.

Due to the high potential for abuse, opioids should not be used routinely for the treatment of migraine.12 There is no high-quality evidence supporting the efficacy of barbiturates (ie, butalbital-containing compounds) for acute migraine treatment.11 Moreover, use of these agents may increase the likelihood of progression from episodic to chronic migraine.16

Gepants for acute migraine treatment

Neuropeptide CGRP is released from trigeminal nerves and is a potent dilator of cerebral and dural vessels, playing a key role in regulating blood flow to the brain. Other roles of CGRP include the release of inflammatory agents from mast cells and the transmission of painful stimuli from intracranial vessels.17 The CGRP receptor or ligand can be targeted by small-molecule receptor antagonists for acute and preventive migraine treatment (and by monoclonal antibodies solely for prevention, discussed later). It has been theorized that gepants bind to CGRP receptors, resulting in decreased blood flow to the brain, inhibition of neurogenic inflammation, and reduced pain signaling.17 Unlike triptans and ergotamine derivatives, these novel treatments do not constrict blood vessels and may have a unique role in patients with contraindications to triptans.

The 3 gepants approved for acute treatment—ubrogepant (Ubrelvy),18 rimegepant (Nurtec),19 and zavegepant (Zavzpret)20—were compared with placebo in clinical trials and were shown to increase the number of patients who were completely pain free at 2 hours, were free of the most bothersome associated symptom (photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea) at 2 hours, and remained pain free at 24 hours (TABLE 418-24).

Continue to: Ubrogrepant

Ubrogepant, in 2 Phase 3 trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) demonstrated effectiveness compared with placebo.21,22 The most common adverse effects reported were nausea and somnolence at very low rates. Pain-relief rates at 2 hours post dose (> 60% of participants) were higher than pain-free rates, and a significantly higher percentage (> 40%) of ubrogepant-treated participants reported ability to function normally on the Functional Disability Scale.25

Rimegepant was also superior to placebo (59% vs 43%) in pain relief at 2 hours post dose and other secondary endpoints.23 Rimegepant also has potential drug interactions

Zavegepant, approved in March 2023, is administered once daily as a 10-mg nasal spray. In its Phase 3 trial, zavegepant was significantly superior to placebo at 2 hours post dose in freedom from pain (24% v 15%), and in freedom from the most bothersome symptom (40% v 31%).24 Dosage modifications are not needed with mild-to-moderate renal or hepatic disease.20

Worth noting. The safety of using ubrogepant to treat more than 8 migraine episodes in a 30-day period has not been established. The safety of using more than 18 doses of zavegepant in a 30-day period also has not been established. With ubrogepant and rimegepant, there are dosing modifications for concomitant use with specific drugs (CYP3A4 inhibitors and inducers) due to potential interactions and in patients with hepatic or renal impairment.18,19

There are no trials comparing efficacy of CGRP antagonists to triptans. Recognizing that these newer medications would be costly, the AHS position statement released in 2019 recommends that gepants be considered for those with contraindications to triptans or for whom at least 2 oral triptans have failed (as determined by a validated patient outcome questionnaire).10 Step therapy with documentation of previous trials and therapy failures is often required by insurance companies prior to gepant coverage.

Continue to: Preventive therapies

Preventive therapies

Preventive migraine therapies are used to reduce duration, frequency, and severity of attacks, the need for acute treatment, and overall headache disability.26 Medications typically are chosen based on efficacy, adverse effect profile, and patient comorbidities. Barriers to successful use include poor patient adherence and tolerability, the need for slow dose titration, and long-term use (minimum of 2 months) at maximum tolerated or minimum effective doses. Medications with established efficacy (Level Aa) based on the 2012 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the AHS are given in TABLE 5.27-29

Drugs having received the strongest level of evidence for migraine prevention are metoprolol, propranolol, timolol, topiramate, valproate sodium, divalproex sodium, and onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox), and frovatriptan for menstrual migraine prevention. Because these guidelines were last updated in 2012, they did not cover gepants (which will be discussed shortly). The AHS released a position statement in 2019 supporting the use of

CGRP-targeted prevention

Four anti-CGRP mAbs and 2 gepants have been approved for migraine prevention in the United States. Differences between products include targets (ligand vs receptor), antibody IgG subtype, bioavailability, route of administration, and frequency of administration.28 As noted in the Phase 3 studies (TABLE 619,30-47), these therapies are highly efficacious, safe, and tolerable.

Gepants. Rimegepant, discussed earlier for migraine treatment, is one of the CGRP receptor antagonists approved for prevention. The other is atogepant (Qulipta), approved only for prevention. Ubrogepant is not approved for prevention.

Anti-CGRP mAb is the only medication class specifically created for migraine prevention.10,26 As already noted, several efficacious non-CGRP treatment options are available for migraine prevention. However, higher doses of those agents, if needed,

Continue to: The targeted anti-CGRP approach...

The targeted anti-CGRP approach, which can be used by patients with liver or kidney disease, results in decreased toxicity and minimal drug interactions. Long half-lives allow for monthly or quarterly injections, possibly resulting in increased compliance.28 Dose titration is not needed, allowing for more rapid symptom management. The large molecular size of a mAb limits its transfer across the blood-brain barrier, making central nervous system adverse effects unlikely.28 Despite the compelling mAb pharmacologic properties, their use may be limited by a lack of long-term safety data and the need for parenteral administration. Although immunogenicity—the development of neutralizing antibodies—can limit long-term tolerability or efficacy of mAbs generally,26,28 anti-CGRP mAbs were engineered to minimally activate the immune system and have not been associated with immune suppression, opportunistic infections, malignancies, or decreased efficacy.28

A pooled meta-analysis including 4 trials (3166 patients) found that CGRP mAbs compared with placebo significantly improved patient response rates, defined as at least a 50% and 75% reduction in monthly headache/migraine days from baseline to Weeks 9 to 12.48 Another meta-analysis including 8 trials (2292 patients) found a significant reduction from baseline in monthly migraine days and monthly acute migraine medication consumption among patients taking CGRP mAbs compared with those taking placebo.49 Open-label extension studies have shown progressive and cumulative benefits in individuals who respond to anti-CGRP mAbs. Therefore, several treatment cycles may be necessary to determine overall efficacy of therapy.10,28

Cost initially can be a barrier. Insurance companies often require step therapy before agreeing to cover mAb therapy, which aligns with the 2019 AHS position statement.10

When combination treatment may be appropriate

Monotherapy is the usual approach to preventing migraine due to advantages of efficacy, simplified regimens, lower cost, and reduced adverse effects.51 However, if a patient does not benefit from monotherapy even after trying dose titrations as tolerated or switching therapies, trying complementary combination therapy is appropriate. Despite a shortage of clinical trials supporting the use of 2 or more preventive medications with different mechanisms of action, this strategy is used clinically.10 Consider combination therapy in those with refractory disease, partial responses, or intolerance to recommended doses.52 Articles reporting on case study reviews have rationalized the combined use of onabotulinumtoxinA and anti-CGRP mAbs, noting better migraine control.51,53 The 2019 AHS position statement recommends adding a mAb to an existing preventive treatment regimen with no other changes until mAb effectiveness is determined, as the risk for drug interactions on dual therapy is low.10 Safety and efficacy also have been demonstrated with the combination of preventive anti-CGRP mAbs and acute treatment with gepants as needed.54

CORRESPONDENCE

Emily Peterson, PharmD, BCACP, 3640 Middlebury Road, Iowa City, IA 52242; Emily-a-peterson@uiowa.edu

1. Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache. 2022;62:122-140. doi: 10.1111/head.14259

2. Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D. Migraine: multiple processes; complext pathophysiology. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6619-6629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015

3. Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, et al. CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies - successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:338-350. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0003-1

4. McGrath K, Rague A, Thesing C, et al. Migraine: expanding our Tx arsenal. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:10-14;16-24.

5. Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet. 2018;391:1315-1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30478-1

6. Agostoni EC, Barbanti P, Calabresi P, et al. Current and emerging evidence-based treatment options in chronic migraine: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:92. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1038-4

7. IHS. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202

8. Do TP, Remmers A, Schytz HW, et al. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Neurology. 2019;92:134-144. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006697

9. NIH. Migraine. Accessed July 30, 2023.

10. AHS. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1-18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456

11. Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55:3-20. doi: 10.1111/head.12499

12. Mayans L, Walling A. Acute migraine headache: treatment strategies. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:243-251.

13. Cameron C, Kelly S, Hsieh SC, et al. Triptans in the acute treatment of migraine: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Headache. 2015;55(suppl 4):221-235. doi: 10.1111/head.12601

14. Becker WJ. Acute migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21:953-972. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000192

15. Migranal (dihydroergotamine mesylate) Package insert. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America; 2019. Accessed June 17, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/020148Orig1s025lbl.pdf

16. Minen MT, Tanev K, Friedman BW. Evaluation and treatment of migraine in the emergency department: a review. Headache. 2014;54:1131-45. doi: 10.1111/head.12399

17. Durham PL. CGRP-receptor antagonists--a fresh approach to migraine therapy? N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1073-1075. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048016

18. Ubrelvy (ubrogepant). Package insert. Allergan, Inc.; 2019. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211765s000lbl.pdf

19. Nurtec ODT (rimegepant sulfate). Package insert. Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/212728s006lbl.pdf

20. Zavzpret (zavegepant). Package insert. Pfizer Labs.; 2023. Accessed July 15, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216386s000lbl.pdf

21. Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2230-2241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813049

22. Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1887-1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711

23. Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:737-745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31606-X

24. Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock DA, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine in the USA: a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:209-217. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00517-8

25. Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant, an acute treatment for migraine, improved patient-reported functional disability and satisfaction in 2 single-attack phase 3 randomized trials, ACHIEVE I and II. Headache. 2020;60:686-700. doi: 10.1111/head.13766

26. Burch R. Migraine and tension-type headache: diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:215-233. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.003

27. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20

28. Dodick DW. CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: evidence review and clinical implications. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:445-458. doi: 10.1177/ 0333102418821662

29. Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Becker WJ. Prophylaxis of migraine headache. CMAJ. 2010;182:E269-276. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081657

30. Vyepti (eptinezumab-jjmr). Package insert. Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals LLV; 2020. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761119s000lbl.pdf

31. Aimovig (erenumab-aooe). Package insert. Amgen Inc.; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761077s009lbl.pdf

32. Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm). Package insert. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; 2018. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761089s000lbl.pdf

33. Emgality (galcanezumab-gnlm). Package insert. Eli Lilly and Company; 2018. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761063s000lbl.pdf

34. Ashina M, Saper J, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia. 2020;40:241-254. doi: 10.1177/0333102420905132

35. Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Smith J, et al. Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine: PROMISE-2. Neurology. 2020;94:e1365-e1377. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009169

36. Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, et al. ARISE: a phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1026-1037. doi: 10.1177/0333102418759786

37. Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2123-2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705848

38. Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet. 2018;392:2280-2287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32534-0

39. Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, et al. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:2113-2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709038

40. Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, et al. Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1999-2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.4853

41. Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, et al. Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1080-1088. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1212

42. Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, et al. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1442-1454. doi: 10.1177/0333102418779543

43. Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, et al. Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology. 2018;91:e2211-e2221. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006640

44. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Leone M, at al. Trial of galcanezumab in prevention of episodic cluster headache. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:132-141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813440

45. Croop R, Lipton RB, Kudrow D, et al. Oral rimegepant for preventive treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:51-60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32544-7

46. Ailani J, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, et al. Atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:695-706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035908

47. Qulipta (atogepant). Package insert. AbbVie; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215206Orig1s000lbl.pdf

48. Han L, Liu Y, Xiong H, et al. CGRP monoclonal antibody for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: an update of meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01215. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1215

49. Zhu Y, Liu Y, Zhao J, et al. The efficacy and safety of calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody for episodic migraine: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2018;39:2097-2106. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3547-3

50. Szperka CL, VanderPluym J, Orr SL, et al. Recommendations on the use of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in children and adolescents. Headache. 2018;58:1658-1669. doi: 10.1111/head.13414

51. Pellesi L, Do TP, Ashina H, et al. Dual therapy with anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies and botulinum toxin for migraine prevention: is there a rationale? Headache. 2020;60:1056-1065. doi: 10.1111/head.13843

52. D’Antona L, Matharu M. Identifying and managing refractory migraine: barriers and opportunities? J Headache Pain. 2019;20:89. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1040-x

53. Cohen F, Armand C, Lipton RB, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of calcitonin gene-related peptide targeted monoclonal antibody medications as add-on therapy to onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine. Pain Med. 2021;1857-1863. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab093

54. Berman G, Croop R, Kudrow D, et al. Safety of rimegepant, an oral CGRP receptor antagonist, plus CGRP monoclonal antibodies for migraine. Headache. 2020;60:1734-1742. doi: 10.1111/head.13930

1. Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache. 2022;62:122-140. doi: 10.1111/head.14259

2. Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D. Migraine: multiple processes; complext pathophysiology. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6619-6629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015

3. Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, et al. CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies - successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:338-350. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0003-1

4. McGrath K, Rague A, Thesing C, et al. Migraine: expanding our Tx arsenal. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:10-14;16-24.

5. Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet. 2018;391:1315-1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30478-1

6. Agostoni EC, Barbanti P, Calabresi P, et al. Current and emerging evidence-based treatment options in chronic migraine: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:92. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1038-4

7. IHS. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202

8. Do TP, Remmers A, Schytz HW, et al. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Neurology. 2019;92:134-144. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006697

9. NIH. Migraine. Accessed July 30, 2023.

10. AHS. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1-18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456

11. Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55:3-20. doi: 10.1111/head.12499

12. Mayans L, Walling A. Acute migraine headache: treatment strategies. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:243-251.

13. Cameron C, Kelly S, Hsieh SC, et al. Triptans in the acute treatment of migraine: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Headache. 2015;55(suppl 4):221-235. doi: 10.1111/head.12601

14. Becker WJ. Acute migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21:953-972. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000192

15. Migranal (dihydroergotamine mesylate) Package insert. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America; 2019. Accessed June 17, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/020148Orig1s025lbl.pdf

16. Minen MT, Tanev K, Friedman BW. Evaluation and treatment of migraine in the emergency department: a review. Headache. 2014;54:1131-45. doi: 10.1111/head.12399

17. Durham PL. CGRP-receptor antagonists--a fresh approach to migraine therapy? N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1073-1075. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048016

18. Ubrelvy (ubrogepant). Package insert. Allergan, Inc.; 2019. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211765s000lbl.pdf

19. Nurtec ODT (rimegepant sulfate). Package insert. Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/212728s006lbl.pdf

20. Zavzpret (zavegepant). Package insert. Pfizer Labs.; 2023. Accessed July 15, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216386s000lbl.pdf

21. Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2230-2241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813049

22. Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1887-1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711

23. Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:737-745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31606-X

24. Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock DA, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of zavegepant 10 mg nasal spray for the acute treatment of migraine in the USA: a phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:209-217. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00517-8

25. Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant, an acute treatment for migraine, improved patient-reported functional disability and satisfaction in 2 single-attack phase 3 randomized trials, ACHIEVE I and II. Headache. 2020;60:686-700. doi: 10.1111/head.13766

26. Burch R. Migraine and tension-type headache: diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:215-233. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.003

27. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20

28. Dodick DW. CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: evidence review and clinical implications. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:445-458. doi: 10.1177/ 0333102418821662

29. Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Becker WJ. Prophylaxis of migraine headache. CMAJ. 2010;182:E269-276. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081657

30. Vyepti (eptinezumab-jjmr). Package insert. Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals LLV; 2020. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761119s000lbl.pdf

31. Aimovig (erenumab-aooe). Package insert. Amgen Inc.; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761077s009lbl.pdf

32. Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm). Package insert. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; 2018. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761089s000lbl.pdf

33. Emgality (galcanezumab-gnlm). Package insert. Eli Lilly and Company; 2018. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/761063s000lbl.pdf

34. Ashina M, Saper J, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia. 2020;40:241-254. doi: 10.1177/0333102420905132

35. Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Smith J, et al. Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine: PROMISE-2. Neurology. 2020;94:e1365-e1377. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009169

36. Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, et al. ARISE: a phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1026-1037. doi: 10.1177/0333102418759786

37. Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2123-2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705848

38. Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet. 2018;392:2280-2287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32534-0

39. Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, et al. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:2113-2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709038

40. Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, et al. Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1999-2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.4853

41. Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, et al. Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1080-1088. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1212

42. Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, et al. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1442-1454. doi: 10.1177/0333102418779543

43. Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, et al. Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology. 2018;91:e2211-e2221. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006640

44. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Leone M, at al. Trial of galcanezumab in prevention of episodic cluster headache. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:132-141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813440

45. Croop R, Lipton RB, Kudrow D, et al. Oral rimegepant for preventive treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:51-60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32544-7

46. Ailani J, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, et al. Atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:695-706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035908

47. Qulipta (atogepant). Package insert. AbbVie; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215206Orig1s000lbl.pdf

48. Han L, Liu Y, Xiong H, et al. CGRP monoclonal antibody for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: an update of meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01215. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1215

49. Zhu Y, Liu Y, Zhao J, et al. The efficacy and safety of calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody for episodic migraine: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2018;39:2097-2106. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3547-3

50. Szperka CL, VanderPluym J, Orr SL, et al. Recommendations on the use of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in children and adolescents. Headache. 2018;58:1658-1669. doi: 10.1111/head.13414

51. Pellesi L, Do TP, Ashina H, et al. Dual therapy with anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies and botulinum toxin for migraine prevention: is there a rationale? Headache. 2020;60:1056-1065. doi: 10.1111/head.13843

52. D’Antona L, Matharu M. Identifying and managing refractory migraine: barriers and opportunities? J Headache Pain. 2019;20:89. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1040-x

53. Cohen F, Armand C, Lipton RB, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of calcitonin gene-related peptide targeted monoclonal antibody medications as add-on therapy to onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine. Pain Med. 2021;1857-1863. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab093

54. Berman G, Croop R, Kudrow D, et al. Safety of rimegepant, an oral CGRP receptor antagonist, plus CGRP monoclonal antibodies for migraine. Headache. 2020;60:1734-1742. doi: 10.1111/head.13930

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider small-molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) for acute migraine treatment after treatment failure of at least 2 non-CGRP first-line therapies. A

› Consider anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies or gepants for migraine prevention if traditional therapies have proven ineffective or are contraindicated or intolerable to the patient. A

› Add an anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody or gepant to existing preventive treatment if the patient continues to experience migraine. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series