User login

Syncope is characterized by sudden transient loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion and is typically associated with an inability to maintain postural tone. There are many different causes and clinical presentations of syncope and the incidence varies depending on the population. Estimated lifetime prevalence rates are as high as 41% for a single episode of syncope, with recurrent syncope occurring in 13.5% of the general population. Incidence follows a trimodal distribution with peaks at age 20, 60, and 80 years for both men and women. The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey reported 6.7 million episodes of syncope in the emergency department, which is where most patients with syncope initially present. However, patients may also present to the primary care outpatient setting, and providers should be equipped for initial evaluation and management.

Previous and current treatment guidelines

Although there have been general reviews published by general and specialty societies, there were no comprehensive guidelines on the evaluation and management of syncope until recently. The 2017 guideline from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society is intended to provide guidance on evaluation and management of syncope, specifically in the context of different clinical settings, specific causes, or selected circumstances.1

What primary care providers should know

A detailed history and physical exam should be performed in all patients with syncope. Useful details include the setting in which syncope occurs, prodromal symptoms, witness reports, postevent symptoms, comorbidities, medication use, past medical history, and family history. The physical exam should include orthostatic vital signs, cardiac exam, neurologic exam, and any other relevant systems. A resting 12-lead ECG in the initial evaluation is recommended to detect underlying arrhythmia or structural heart disease (Class I recommendation – strong).

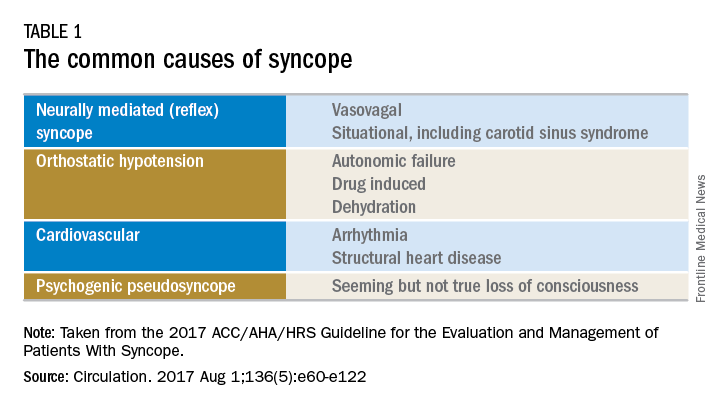

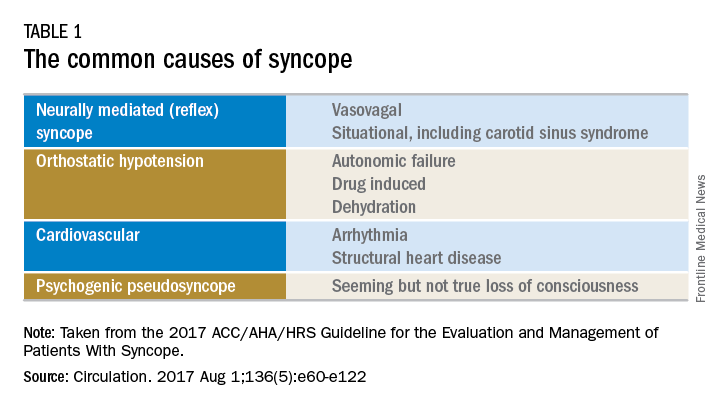

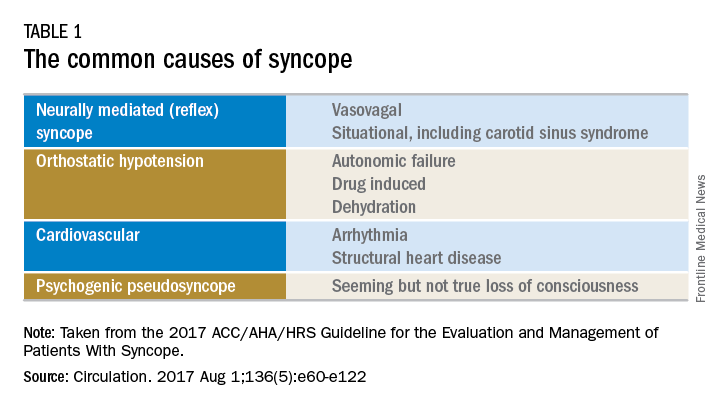

There are many different causes of syncope (see Table 1). Vasovagal syncope, a form of reflex syncope mediated by the vasovagal reflex, is the most common cause of syncope and a frequent reason for emergency department visits. There is often a prodrome of diaphoresis, warmth, nausea, and/or pallor, often followed by fatigue. The diagnosis can be made by the history, physical exam, and eyewitness observation.

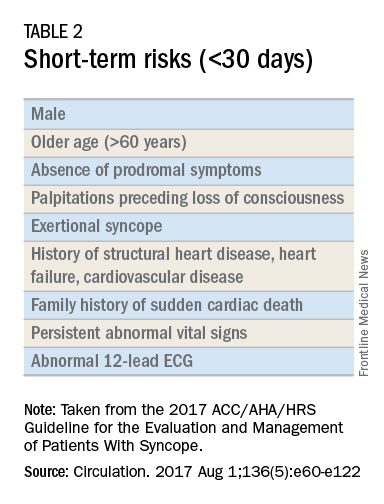

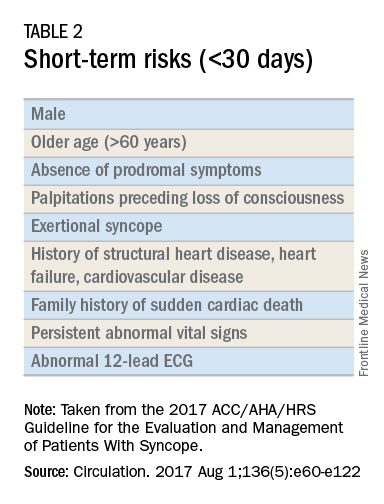

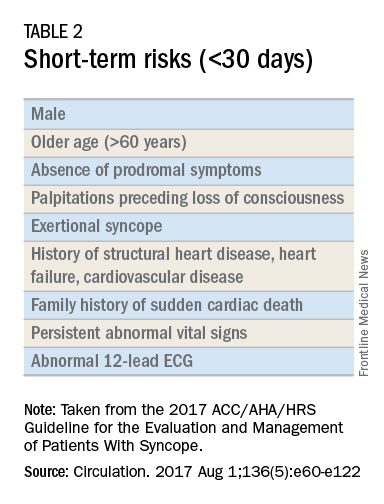

Once the initial evaluation is complete, further evaluation and management depends on the presence of risk factors presented in Table 2. Outpatient management is reasonable for patients with presumptive reflex-mediated syncope when there is an absence of serious medical conditions such as cardiac disease or comorbid neurologic disease. While hospital-based evaluation has not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with a low risk profile, hospital-based evaluation and treatment are recommended for patients presenting with syncope who have a serious medical condition potentially relevant to the cause of syncope.2 Serious medical conditions that require hospital management include arrhythmia, cardiac ischemia, severe aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection, acute heart failure, severe anemia, or major traumatic injury. Finally, patients with intermediate risk may benefit from an observational protocol in the emergency department.

Routine and comprehensive laboratory testing is not useful in syncope work-up (Class III recommendation – no benefit). Routine cardiac imaging is not recommended unless a cardiac etiology is suspected and routine neurological imaging and EEG are not recommended in the absence of focal neurologic findings. Additional work-up may be indicated if initial evaluation suggests a more specific etiology. If the initial evaluation suggests neurogenic orthostatic hypotension but the diagnosis is not clear, then referral for an autonomic evaluation is reasonable. If reflex syncope is suspected, tilt-table testing may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis. Lastly, if a cardiovascular etiology is suspected, it is recommended that the patient have cardiac monitoring in the acute care setting. In this later group, stress testing, transthoracic echocardiogram, electrophysiology study, and/or MRI or CT may be useful. Electrophysiologic testing is reasonable in patients with suspected arrhythmia as the etiology for syncope (Class IIa recommendation – moderate strength). The guideline provides a convenient summary algorithm to approach the initial and subsequent evaluations for syncope based on the initial evaluation and presenting symptoms.

Special populations

There are specific considerations for certain populations. In the pediatric population, the vast majority of syncopal episodes are reflex syncope but breath-holding spells should also be considered. In the geriatric population, particularly individuals older than 75 years, the incidence of syncope is high, the differential diagnosis is broad, and the diagnosis may be imprecise given amnesia, falls, lack of witnesses, and polypharmacy. In this group, morbidity is high because of multimorbidity and frailty. A careful history and physical exam with orthostatic vital signs is important, as is a multidisciplinary approach with geriatric consultation when needed.

Summary

Syncope is a common clinical syndrome often presenting to the emergency department or primary care setting. There are many causes, the most common being vasovagal syncope. In the initial evaluation, providers should perform a detailed history and physical exam, check orthostatic signs and perform a 12-lead ECG. Patients can be evaluated and managed safely in the outpatient setting in the absence of risk factors. Routine comprehensive laboratory testing and cardiac imaging are often not needed. For patients with defined risk factors, a more detailed evaluation in the hospital is recommended.

Dr. Li is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program in the department of family and community medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the departments of family and community medicine and physiology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

References

1. Shen W, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e60-e122. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000499. Epub 2017 Mar 9.

2. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):878-85.

Syncope is characterized by sudden transient loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion and is typically associated with an inability to maintain postural tone. There are many different causes and clinical presentations of syncope and the incidence varies depending on the population. Estimated lifetime prevalence rates are as high as 41% for a single episode of syncope, with recurrent syncope occurring in 13.5% of the general population. Incidence follows a trimodal distribution with peaks at age 20, 60, and 80 years for both men and women. The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey reported 6.7 million episodes of syncope in the emergency department, which is where most patients with syncope initially present. However, patients may also present to the primary care outpatient setting, and providers should be equipped for initial evaluation and management.

Previous and current treatment guidelines

Although there have been general reviews published by general and specialty societies, there were no comprehensive guidelines on the evaluation and management of syncope until recently. The 2017 guideline from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society is intended to provide guidance on evaluation and management of syncope, specifically in the context of different clinical settings, specific causes, or selected circumstances.1

What primary care providers should know

A detailed history and physical exam should be performed in all patients with syncope. Useful details include the setting in which syncope occurs, prodromal symptoms, witness reports, postevent symptoms, comorbidities, medication use, past medical history, and family history. The physical exam should include orthostatic vital signs, cardiac exam, neurologic exam, and any other relevant systems. A resting 12-lead ECG in the initial evaluation is recommended to detect underlying arrhythmia or structural heart disease (Class I recommendation – strong).

There are many different causes of syncope (see Table 1). Vasovagal syncope, a form of reflex syncope mediated by the vasovagal reflex, is the most common cause of syncope and a frequent reason for emergency department visits. There is often a prodrome of diaphoresis, warmth, nausea, and/or pallor, often followed by fatigue. The diagnosis can be made by the history, physical exam, and eyewitness observation.

Once the initial evaluation is complete, further evaluation and management depends on the presence of risk factors presented in Table 2. Outpatient management is reasonable for patients with presumptive reflex-mediated syncope when there is an absence of serious medical conditions such as cardiac disease or comorbid neurologic disease. While hospital-based evaluation has not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with a low risk profile, hospital-based evaluation and treatment are recommended for patients presenting with syncope who have a serious medical condition potentially relevant to the cause of syncope.2 Serious medical conditions that require hospital management include arrhythmia, cardiac ischemia, severe aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection, acute heart failure, severe anemia, or major traumatic injury. Finally, patients with intermediate risk may benefit from an observational protocol in the emergency department.

Routine and comprehensive laboratory testing is not useful in syncope work-up (Class III recommendation – no benefit). Routine cardiac imaging is not recommended unless a cardiac etiology is suspected and routine neurological imaging and EEG are not recommended in the absence of focal neurologic findings. Additional work-up may be indicated if initial evaluation suggests a more specific etiology. If the initial evaluation suggests neurogenic orthostatic hypotension but the diagnosis is not clear, then referral for an autonomic evaluation is reasonable. If reflex syncope is suspected, tilt-table testing may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis. Lastly, if a cardiovascular etiology is suspected, it is recommended that the patient have cardiac monitoring in the acute care setting. In this later group, stress testing, transthoracic echocardiogram, electrophysiology study, and/or MRI or CT may be useful. Electrophysiologic testing is reasonable in patients with suspected arrhythmia as the etiology for syncope (Class IIa recommendation – moderate strength). The guideline provides a convenient summary algorithm to approach the initial and subsequent evaluations for syncope based on the initial evaluation and presenting symptoms.

Special populations

There are specific considerations for certain populations. In the pediatric population, the vast majority of syncopal episodes are reflex syncope but breath-holding spells should also be considered. In the geriatric population, particularly individuals older than 75 years, the incidence of syncope is high, the differential diagnosis is broad, and the diagnosis may be imprecise given amnesia, falls, lack of witnesses, and polypharmacy. In this group, morbidity is high because of multimorbidity and frailty. A careful history and physical exam with orthostatic vital signs is important, as is a multidisciplinary approach with geriatric consultation when needed.

Summary

Syncope is a common clinical syndrome often presenting to the emergency department or primary care setting. There are many causes, the most common being vasovagal syncope. In the initial evaluation, providers should perform a detailed history and physical exam, check orthostatic signs and perform a 12-lead ECG. Patients can be evaluated and managed safely in the outpatient setting in the absence of risk factors. Routine comprehensive laboratory testing and cardiac imaging are often not needed. For patients with defined risk factors, a more detailed evaluation in the hospital is recommended.

Dr. Li is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program in the department of family and community medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the departments of family and community medicine and physiology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

References

1. Shen W, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e60-e122. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000499. Epub 2017 Mar 9.

2. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):878-85.

Syncope is characterized by sudden transient loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion and is typically associated with an inability to maintain postural tone. There are many different causes and clinical presentations of syncope and the incidence varies depending on the population. Estimated lifetime prevalence rates are as high as 41% for a single episode of syncope, with recurrent syncope occurring in 13.5% of the general population. Incidence follows a trimodal distribution with peaks at age 20, 60, and 80 years for both men and women. The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey reported 6.7 million episodes of syncope in the emergency department, which is where most patients with syncope initially present. However, patients may also present to the primary care outpatient setting, and providers should be equipped for initial evaluation and management.

Previous and current treatment guidelines

Although there have been general reviews published by general and specialty societies, there were no comprehensive guidelines on the evaluation and management of syncope until recently. The 2017 guideline from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society is intended to provide guidance on evaluation and management of syncope, specifically in the context of different clinical settings, specific causes, or selected circumstances.1

What primary care providers should know

A detailed history and physical exam should be performed in all patients with syncope. Useful details include the setting in which syncope occurs, prodromal symptoms, witness reports, postevent symptoms, comorbidities, medication use, past medical history, and family history. The physical exam should include orthostatic vital signs, cardiac exam, neurologic exam, and any other relevant systems. A resting 12-lead ECG in the initial evaluation is recommended to detect underlying arrhythmia or structural heart disease (Class I recommendation – strong).

There are many different causes of syncope (see Table 1). Vasovagal syncope, a form of reflex syncope mediated by the vasovagal reflex, is the most common cause of syncope and a frequent reason for emergency department visits. There is often a prodrome of diaphoresis, warmth, nausea, and/or pallor, often followed by fatigue. The diagnosis can be made by the history, physical exam, and eyewitness observation.

Once the initial evaluation is complete, further evaluation and management depends on the presence of risk factors presented in Table 2. Outpatient management is reasonable for patients with presumptive reflex-mediated syncope when there is an absence of serious medical conditions such as cardiac disease or comorbid neurologic disease. While hospital-based evaluation has not been shown to improve outcomes in patients with a low risk profile, hospital-based evaluation and treatment are recommended for patients presenting with syncope who have a serious medical condition potentially relevant to the cause of syncope.2 Serious medical conditions that require hospital management include arrhythmia, cardiac ischemia, severe aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection, acute heart failure, severe anemia, or major traumatic injury. Finally, patients with intermediate risk may benefit from an observational protocol in the emergency department.

Routine and comprehensive laboratory testing is not useful in syncope work-up (Class III recommendation – no benefit). Routine cardiac imaging is not recommended unless a cardiac etiology is suspected and routine neurological imaging and EEG are not recommended in the absence of focal neurologic findings. Additional work-up may be indicated if initial evaluation suggests a more specific etiology. If the initial evaluation suggests neurogenic orthostatic hypotension but the diagnosis is not clear, then referral for an autonomic evaluation is reasonable. If reflex syncope is suspected, tilt-table testing may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis. Lastly, if a cardiovascular etiology is suspected, it is recommended that the patient have cardiac monitoring in the acute care setting. In this later group, stress testing, transthoracic echocardiogram, electrophysiology study, and/or MRI or CT may be useful. Electrophysiologic testing is reasonable in patients with suspected arrhythmia as the etiology for syncope (Class IIa recommendation – moderate strength). The guideline provides a convenient summary algorithm to approach the initial and subsequent evaluations for syncope based on the initial evaluation and presenting symptoms.

Special populations

There are specific considerations for certain populations. In the pediatric population, the vast majority of syncopal episodes are reflex syncope but breath-holding spells should also be considered. In the geriatric population, particularly individuals older than 75 years, the incidence of syncope is high, the differential diagnosis is broad, and the diagnosis may be imprecise given amnesia, falls, lack of witnesses, and polypharmacy. In this group, morbidity is high because of multimorbidity and frailty. A careful history and physical exam with orthostatic vital signs is important, as is a multidisciplinary approach with geriatric consultation when needed.

Summary

Syncope is a common clinical syndrome often presenting to the emergency department or primary care setting. There are many causes, the most common being vasovagal syncope. In the initial evaluation, providers should perform a detailed history and physical exam, check orthostatic signs and perform a 12-lead ECG. Patients can be evaluated and managed safely in the outpatient setting in the absence of risk factors. Routine comprehensive laboratory testing and cardiac imaging are often not needed. For patients with defined risk factors, a more detailed evaluation in the hospital is recommended.

Dr. Li is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program in the department of family and community medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. Dr. Mills is assistant residency program director and assistant professor in the departments of family and community medicine and physiology at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

References

1. Shen W, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e60-e122. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000499. Epub 2017 Mar 9.

2. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):878-85.