User login

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

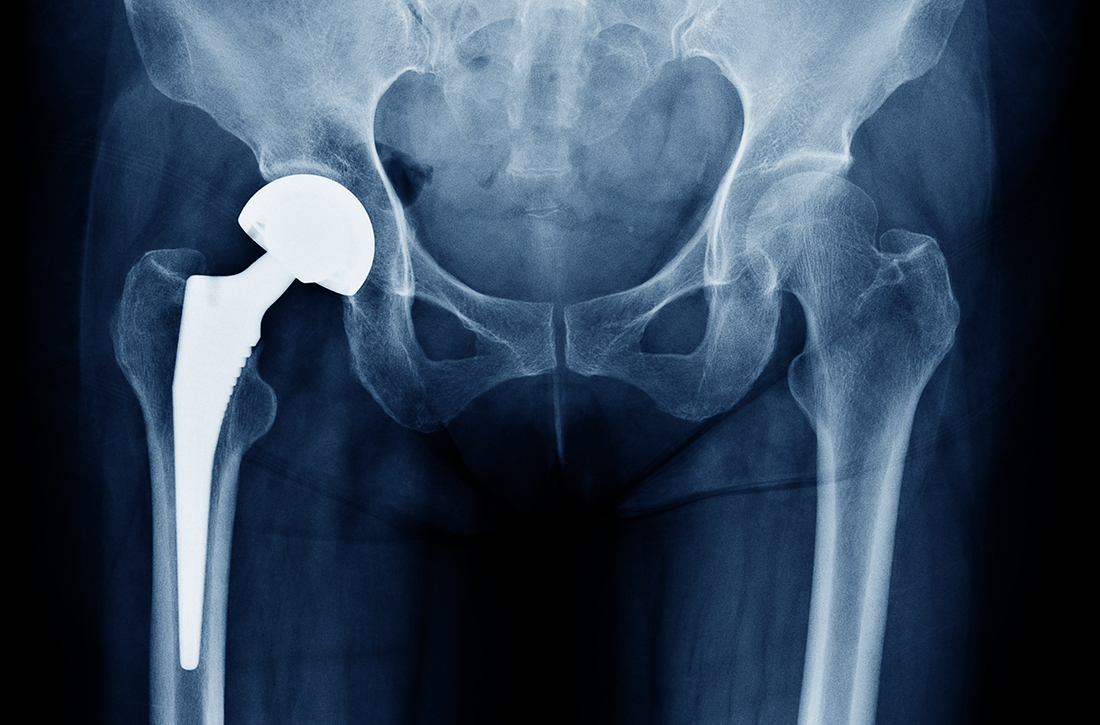

A 72-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is scheduled for right total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to severe arthritis. He will be admitted to the hospital overnight, and his orthopedic surgeon anticipates 2 to 3 days of inpatient recovery time. In addition to medical management of the patient’s comorbid conditions, the surgeon asks if you have any insight regarding VTE prophylaxis for this patient. Specifically, do you think aspirin is equal to LMWH for VTE prophylaxis?

All adults undergoing major orthopedic surgery are considered to be at high risk for postoperative VTE development, with those having lower-limb procedures at highest risk.2 Of the more than 2.2 million THAs and total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) performed in the United States between 2012 and 2020, 55% were primary TKAs and 39% primary THAs.3 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) estimated a baseline 35-day risk for VTE of 4.3% in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.4 The highest VTE risk occurs during the first 7 to 14 days post surgery (1.8% for symptomatic deep vein thrombosis [DVT] and 1% for pulmonary embolism [PE]), with a slightly lower risk during the subsequent 15 to 35 days (1% for symptomatic DVT and 0.5% for PE).4

Aspirin’s low cost, availability, and ease of administration make it an attractive choice for VTE prevention in patients post THA and TKA surgery. The Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial evaluated 13,356 patients undergoing hip fracture repair and 4088 patients undergoing arthroplasty and found aspirin to be safe and effective in prevention of VTEs compared with placebo. The investigators concluded that “there is now good evidence for considering aspirin routinely in a wide range of surgical and medical groups at high risk of venous thromboembolism.”5 The PEP study, along with others, led to the emergence of aspirin monotherapy for VTE prophylaxis.

Current guidelines for perioperative VTE prophylaxis are based on American Society of Hematology (ASH) and ACCP recommendations. For patients undergoing THA or TKA, ASH suggests using aspirin or anticoagulants for VTE prophylaxis; when anticoagulants are used, they suggest using a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over LMWH.6 The ASH guidelines are conditional recommendations based on very low certainty of effects, and the ASH panel recognized the need for further investigation with large, high-quality clinical trials.

The ACCP guidelines are clearer in recommending VTE prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis for major orthopedic surgeries and recommend the use of LMWH over other agents, including aspirin, DOACs, warfarin, and intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices.4

Although prophylaxis is widely recommended to mitigate the elevated risk for VTE among patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, aspirin as monotherapy remains controversial.7 Many orthopedic surgeons prescribe aspirin as a sole VTE prophylaxis agent; however, this practice is not well supported by data from large, well-conducted, randomized trials or inferiority trials.2

STUDY SUMMARY

Aspirin did not meet the noninferiority criterion for postoperative VTE

The CRISTAL trial compared the use of aspirin vs LMWH (enoxaparin) for VTE prophylaxis in patients ages 18 years or older undergoing primary THA or TKA for osteoarthritis.1 This Australian study used a cluster-randomized, crossover, registry-nested, noninferiority trial design. Of note, in Australia, aspirin is formulated in 100-mg tablets, equivalent to the standard 81-mg low-dose tablet in the United States.

Continue to: Patients taking prescribed antiplatelet...

Patients taking prescribed antiplatelet medication for preexisting conditions (~20% of patients in each group) were allowed to continue antiplatelet therapy during the trial. Patients were excluded if they were receiving an anticoagulant prior to their procedure or had a medical contraindication to aspirin or enoxaparin.

Thirty-one hospital sites were randomly assigned a treatment protocol using either aspirin or enoxaparin. Once target patient enrollment was met with the initial assigned medication, the site switched to the second/other agent. This resulted in 5675 patients in the aspirin group and 4036 in the enoxaparin group enrolled between April 2019 and December 2020, with final follow-up in August 2021; of these, 259 in the aspirin group and 249 in the enoxaparin group were lost to follow-up, opted out, or died.

The aspirin group was given 100 mg PO daily and the enoxaparin group was given 40 mg SC daily (20 mg daily for patients weighing < 50 kg or with an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) for 35 days after THA and 14 days after TKA. Both treatment groups received IPC calf devices intraoperatively and postoperatively, and mobilization was offered on postoperative Day 0 or 1.

The primary outcome—development of symptomatic VTE within 90 days of the procedure—occurred in 187 (3.5%) patients in the aspirin group and 69 (1.8%) patients in the enoxaparin group (estimated difference = 1.97%; 95% CI, 0.54%-3.41%). This did not meet the noninferiority criterion for aspirin, based on an estimated assumed rate of 2% and a noninferiority margin of 1%, and in fact was statistically superior for enoxaparin (P = .007). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in major bleeding or death within 90 days.1

WHAT’S NEW

Enoxaparin was significantly superior to aspirin for VTE prophylaxis

Although this study was designed as a noninferiority trial, analysis showed enoxaparin to be significantly superior for postoperative VTE prophylaxis compared with aspirin.

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Study aspirin dosing differed from US standard

This study showed significantly lower rates of symptomatic VTE in the enoxaparin group compared with the aspirin group; however, the majority of this difference was driven by rates of below-the-knee DVTs, which are clinically less relevant.8 Also, this trial used a 100-mg aspirin formulation, which is not available in the United States.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Aspirin is far cheaper and administered orally

Aspirin is significantly cheaper than enoxaparin, costing about $0.13 per dose (~$4 for 30 tablets at the 81-mg dose) vs roughly $9 per 40 mg/0.4 mL dose for enoxaparin.9 However, a cost-effectiveness analysis may be useful to determine (for example) whether the higher cost of enoxaparin may be offset by fewer DVTs and other sequelae. Lastly, LMWH is an injection, which some patients may refuse.

1. CRISTAL Study Group; Sidhu VS, Kelly TL, Pratt N, et al. Effect of aspirin vs enoxaparin on symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty: the CRISTAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2022;328:719-727. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.13416

2. Douketis JD, Mithoowani S. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in adults undergoing hip fracture repair or hip or knee replacement. UpToDate. Updated January 25, 2023. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-venous-thromboembolism-in-adults-undergoing-hip-fracture-repair-or-hip-or-knee-replacement

3. Siddiqi A, Levine BR, Springer BD. Highlights of the 2021 American Joint Replacement Registry annual report. Arthroplast Today. 2022;13:205-207. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2022.01.020

4. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S-e325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404

5. Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial Collaborative Group. Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1295-1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02110-3

6. Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3898-3944. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000975

7. Matharu GS, Kunutsor SK, Judge A, et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip and knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:376-384. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6108

8. Brett AS, Friedman RJ. Aspirin vs. enoxaparin for prophylaxis after hip or knee replacement. NEJM Journal Watch. September 15, 2022. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.jwatch.org/na55272/2022/09/15/aspirin-vs-enoxaparin-prophylaxis-after-hip-or-knee

9. Enoxaparin. GoodRx. Accessed August 7, 2023. www.goodrx.com/enoxaparin

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 72-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is scheduled for right total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to severe arthritis. He will be admitted to the hospital overnight, and his orthopedic surgeon anticipates 2 to 3 days of inpatient recovery time. In addition to medical management of the patient’s comorbid conditions, the surgeon asks if you have any insight regarding VTE prophylaxis for this patient. Specifically, do you think aspirin is equal to LMWH for VTE prophylaxis?

All adults undergoing major orthopedic surgery are considered to be at high risk for postoperative VTE development, with those having lower-limb procedures at highest risk.2 Of the more than 2.2 million THAs and total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) performed in the United States between 2012 and 2020, 55% were primary TKAs and 39% primary THAs.3 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) estimated a baseline 35-day risk for VTE of 4.3% in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.4 The highest VTE risk occurs during the first 7 to 14 days post surgery (1.8% for symptomatic deep vein thrombosis [DVT] and 1% for pulmonary embolism [PE]), with a slightly lower risk during the subsequent 15 to 35 days (1% for symptomatic DVT and 0.5% for PE).4

Aspirin’s low cost, availability, and ease of administration make it an attractive choice for VTE prevention in patients post THA and TKA surgery. The Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial evaluated 13,356 patients undergoing hip fracture repair and 4088 patients undergoing arthroplasty and found aspirin to be safe and effective in prevention of VTEs compared with placebo. The investigators concluded that “there is now good evidence for considering aspirin routinely in a wide range of surgical and medical groups at high risk of venous thromboembolism.”5 The PEP study, along with others, led to the emergence of aspirin monotherapy for VTE prophylaxis.

Current guidelines for perioperative VTE prophylaxis are based on American Society of Hematology (ASH) and ACCP recommendations. For patients undergoing THA or TKA, ASH suggests using aspirin or anticoagulants for VTE prophylaxis; when anticoagulants are used, they suggest using a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over LMWH.6 The ASH guidelines are conditional recommendations based on very low certainty of effects, and the ASH panel recognized the need for further investigation with large, high-quality clinical trials.

The ACCP guidelines are clearer in recommending VTE prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis for major orthopedic surgeries and recommend the use of LMWH over other agents, including aspirin, DOACs, warfarin, and intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices.4

Although prophylaxis is widely recommended to mitigate the elevated risk for VTE among patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, aspirin as monotherapy remains controversial.7 Many orthopedic surgeons prescribe aspirin as a sole VTE prophylaxis agent; however, this practice is not well supported by data from large, well-conducted, randomized trials or inferiority trials.2

STUDY SUMMARY

Aspirin did not meet the noninferiority criterion for postoperative VTE

The CRISTAL trial compared the use of aspirin vs LMWH (enoxaparin) for VTE prophylaxis in patients ages 18 years or older undergoing primary THA or TKA for osteoarthritis.1 This Australian study used a cluster-randomized, crossover, registry-nested, noninferiority trial design. Of note, in Australia, aspirin is formulated in 100-mg tablets, equivalent to the standard 81-mg low-dose tablet in the United States.

Continue to: Patients taking prescribed antiplatelet...

Patients taking prescribed antiplatelet medication for preexisting conditions (~20% of patients in each group) were allowed to continue antiplatelet therapy during the trial. Patients were excluded if they were receiving an anticoagulant prior to their procedure or had a medical contraindication to aspirin or enoxaparin.

Thirty-one hospital sites were randomly assigned a treatment protocol using either aspirin or enoxaparin. Once target patient enrollment was met with the initial assigned medication, the site switched to the second/other agent. This resulted in 5675 patients in the aspirin group and 4036 in the enoxaparin group enrolled between April 2019 and December 2020, with final follow-up in August 2021; of these, 259 in the aspirin group and 249 in the enoxaparin group were lost to follow-up, opted out, or died.

The aspirin group was given 100 mg PO daily and the enoxaparin group was given 40 mg SC daily (20 mg daily for patients weighing < 50 kg or with an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) for 35 days after THA and 14 days after TKA. Both treatment groups received IPC calf devices intraoperatively and postoperatively, and mobilization was offered on postoperative Day 0 or 1.

The primary outcome—development of symptomatic VTE within 90 days of the procedure—occurred in 187 (3.5%) patients in the aspirin group and 69 (1.8%) patients in the enoxaparin group (estimated difference = 1.97%; 95% CI, 0.54%-3.41%). This did not meet the noninferiority criterion for aspirin, based on an estimated assumed rate of 2% and a noninferiority margin of 1%, and in fact was statistically superior for enoxaparin (P = .007). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in major bleeding or death within 90 days.1

WHAT’S NEW

Enoxaparin was significantly superior to aspirin for VTE prophylaxis

Although this study was designed as a noninferiority trial, analysis showed enoxaparin to be significantly superior for postoperative VTE prophylaxis compared with aspirin.

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Study aspirin dosing differed from US standard

This study showed significantly lower rates of symptomatic VTE in the enoxaparin group compared with the aspirin group; however, the majority of this difference was driven by rates of below-the-knee DVTs, which are clinically less relevant.8 Also, this trial used a 100-mg aspirin formulation, which is not available in the United States.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Aspirin is far cheaper and administered orally

Aspirin is significantly cheaper than enoxaparin, costing about $0.13 per dose (~$4 for 30 tablets at the 81-mg dose) vs roughly $9 per 40 mg/0.4 mL dose for enoxaparin.9 However, a cost-effectiveness analysis may be useful to determine (for example) whether the higher cost of enoxaparin may be offset by fewer DVTs and other sequelae. Lastly, LMWH is an injection, which some patients may refuse.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 72-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is scheduled for right total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to severe arthritis. He will be admitted to the hospital overnight, and his orthopedic surgeon anticipates 2 to 3 days of inpatient recovery time. In addition to medical management of the patient’s comorbid conditions, the surgeon asks if you have any insight regarding VTE prophylaxis for this patient. Specifically, do you think aspirin is equal to LMWH for VTE prophylaxis?

All adults undergoing major orthopedic surgery are considered to be at high risk for postoperative VTE development, with those having lower-limb procedures at highest risk.2 Of the more than 2.2 million THAs and total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) performed in the United States between 2012 and 2020, 55% were primary TKAs and 39% primary THAs.3 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) estimated a baseline 35-day risk for VTE of 4.3% in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.4 The highest VTE risk occurs during the first 7 to 14 days post surgery (1.8% for symptomatic deep vein thrombosis [DVT] and 1% for pulmonary embolism [PE]), with a slightly lower risk during the subsequent 15 to 35 days (1% for symptomatic DVT and 0.5% for PE).4

Aspirin’s low cost, availability, and ease of administration make it an attractive choice for VTE prevention in patients post THA and TKA surgery. The Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial evaluated 13,356 patients undergoing hip fracture repair and 4088 patients undergoing arthroplasty and found aspirin to be safe and effective in prevention of VTEs compared with placebo. The investigators concluded that “there is now good evidence for considering aspirin routinely in a wide range of surgical and medical groups at high risk of venous thromboembolism.”5 The PEP study, along with others, led to the emergence of aspirin monotherapy for VTE prophylaxis.

Current guidelines for perioperative VTE prophylaxis are based on American Society of Hematology (ASH) and ACCP recommendations. For patients undergoing THA or TKA, ASH suggests using aspirin or anticoagulants for VTE prophylaxis; when anticoagulants are used, they suggest using a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) over LMWH.6 The ASH guidelines are conditional recommendations based on very low certainty of effects, and the ASH panel recognized the need for further investigation with large, high-quality clinical trials.

The ACCP guidelines are clearer in recommending VTE prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis for major orthopedic surgeries and recommend the use of LMWH over other agents, including aspirin, DOACs, warfarin, and intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices.4

Although prophylaxis is widely recommended to mitigate the elevated risk for VTE among patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, aspirin as monotherapy remains controversial.7 Many orthopedic surgeons prescribe aspirin as a sole VTE prophylaxis agent; however, this practice is not well supported by data from large, well-conducted, randomized trials or inferiority trials.2

STUDY SUMMARY

Aspirin did not meet the noninferiority criterion for postoperative VTE

The CRISTAL trial compared the use of aspirin vs LMWH (enoxaparin) for VTE prophylaxis in patients ages 18 years or older undergoing primary THA or TKA for osteoarthritis.1 This Australian study used a cluster-randomized, crossover, registry-nested, noninferiority trial design. Of note, in Australia, aspirin is formulated in 100-mg tablets, equivalent to the standard 81-mg low-dose tablet in the United States.

Continue to: Patients taking prescribed antiplatelet...

Patients taking prescribed antiplatelet medication for preexisting conditions (~20% of patients in each group) were allowed to continue antiplatelet therapy during the trial. Patients were excluded if they were receiving an anticoagulant prior to their procedure or had a medical contraindication to aspirin or enoxaparin.

Thirty-one hospital sites were randomly assigned a treatment protocol using either aspirin or enoxaparin. Once target patient enrollment was met with the initial assigned medication, the site switched to the second/other agent. This resulted in 5675 patients in the aspirin group and 4036 in the enoxaparin group enrolled between April 2019 and December 2020, with final follow-up in August 2021; of these, 259 in the aspirin group and 249 in the enoxaparin group were lost to follow-up, opted out, or died.

The aspirin group was given 100 mg PO daily and the enoxaparin group was given 40 mg SC daily (20 mg daily for patients weighing < 50 kg or with an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) for 35 days after THA and 14 days after TKA. Both treatment groups received IPC calf devices intraoperatively and postoperatively, and mobilization was offered on postoperative Day 0 or 1.

The primary outcome—development of symptomatic VTE within 90 days of the procedure—occurred in 187 (3.5%) patients in the aspirin group and 69 (1.8%) patients in the enoxaparin group (estimated difference = 1.97%; 95% CI, 0.54%-3.41%). This did not meet the noninferiority criterion for aspirin, based on an estimated assumed rate of 2% and a noninferiority margin of 1%, and in fact was statistically superior for enoxaparin (P = .007). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in major bleeding or death within 90 days.1

WHAT’S NEW

Enoxaparin was significantly superior to aspirin for VTE prophylaxis

Although this study was designed as a noninferiority trial, analysis showed enoxaparin to be significantly superior for postoperative VTE prophylaxis compared with aspirin.

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Study aspirin dosing differed from US standard

This study showed significantly lower rates of symptomatic VTE in the enoxaparin group compared with the aspirin group; however, the majority of this difference was driven by rates of below-the-knee DVTs, which are clinically less relevant.8 Also, this trial used a 100-mg aspirin formulation, which is not available in the United States.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Aspirin is far cheaper and administered orally

Aspirin is significantly cheaper than enoxaparin, costing about $0.13 per dose (~$4 for 30 tablets at the 81-mg dose) vs roughly $9 per 40 mg/0.4 mL dose for enoxaparin.9 However, a cost-effectiveness analysis may be useful to determine (for example) whether the higher cost of enoxaparin may be offset by fewer DVTs and other sequelae. Lastly, LMWH is an injection, which some patients may refuse.

1. CRISTAL Study Group; Sidhu VS, Kelly TL, Pratt N, et al. Effect of aspirin vs enoxaparin on symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty: the CRISTAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2022;328:719-727. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.13416

2. Douketis JD, Mithoowani S. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in adults undergoing hip fracture repair or hip or knee replacement. UpToDate. Updated January 25, 2023. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-venous-thromboembolism-in-adults-undergoing-hip-fracture-repair-or-hip-or-knee-replacement

3. Siddiqi A, Levine BR, Springer BD. Highlights of the 2021 American Joint Replacement Registry annual report. Arthroplast Today. 2022;13:205-207. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2022.01.020

4. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S-e325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404

5. Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial Collaborative Group. Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1295-1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02110-3

6. Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3898-3944. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000975

7. Matharu GS, Kunutsor SK, Judge A, et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip and knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:376-384. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6108

8. Brett AS, Friedman RJ. Aspirin vs. enoxaparin for prophylaxis after hip or knee replacement. NEJM Journal Watch. September 15, 2022. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.jwatch.org/na55272/2022/09/15/aspirin-vs-enoxaparin-prophylaxis-after-hip-or-knee

9. Enoxaparin. GoodRx. Accessed August 7, 2023. www.goodrx.com/enoxaparin

1. CRISTAL Study Group; Sidhu VS, Kelly TL, Pratt N, et al. Effect of aspirin vs enoxaparin on symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty: the CRISTAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2022;328:719-727. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.13416

2. Douketis JD, Mithoowani S. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in adults undergoing hip fracture repair or hip or knee replacement. UpToDate. Updated January 25, 2023. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-venous-thromboembolism-in-adults-undergoing-hip-fracture-repair-or-hip-or-knee-replacement

3. Siddiqi A, Levine BR, Springer BD. Highlights of the 2021 American Joint Replacement Registry annual report. Arthroplast Today. 2022;13:205-207. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2022.01.020

4. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S-e325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404

5. Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial Collaborative Group. Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1295-1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02110-3

6. Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3898-3944. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000975

7. Matharu GS, Kunutsor SK, Judge A, et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip and knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:376-384. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6108

8. Brett AS, Friedman RJ. Aspirin vs. enoxaparin for prophylaxis after hip or knee replacement. NEJM Journal Watch. September 15, 2022. Accessed May 24, 2023. www.jwatch.org/na55272/2022/09/15/aspirin-vs-enoxaparin-prophylaxis-after-hip-or-knee

9. Enoxaparin. GoodRx. Accessed August 7, 2023. www.goodrx.com/enoxaparin

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) rather than aspirin to prevent postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single cluster-randomized crossover trial.1