User login

Insomnia disorder is common throughout the lifespan, affecting up to 22% of the population.1 Insomnia has a negative effect on patients’ quality of life and is associated with reported worse health-related quality of life, greater overall work impairment, and higher utilization of health care resources compared to patients without insomnia.2

Fortunately, many validated diagnostic tools are available to support physicians in the care of affected patients. In addition, many pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options exist. This review endeavors to help you refine the care you provide to patients across the lifespan by reviewing the evidence-based strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in children, adolescents, and adults.

Defining insomnia

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) defines insomnia disorder as a predominant complaint of dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, associated with 1 or more of the following3:

1. Difficulty initiating sleep. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty initiating sleep without caregiver intervention.)

2. Difficulty maintaining sleep, characterized by frequent awakenings or problems returning to sleep after awakenings. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty returning to sleep without caregiver intervention.)

3. Early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep.

Sleep difficulty must be present for at least 3 months and must occur at least 3 nights per week to be classified as persistent insomnia.3 If symptoms last fewer than 3 months, insomnia is considered acute, which has a different DSM-5 code ("other specified insomnia disorder").3 Primary insomnia is its own diagnosis that cannot be defined by other sleep-wake cycle disorders, mental health conditions, or medical diagnoses that cause sleep disturbances, nor is it attributable to the physiologic effects of a substance (eg, substance use disorders, medication effects).3

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3) notably consolidates all insomnia diagnoses (ie, “primary” and “comorbid”) under a single diagnosis (“chronic insomnia disorder”), which is a distinction from the DSM-5 diagnosis in terms of classification.4 Diagnosis of insomnia requires the presence of 3 criteria: (1) persistence of sleep difficulty, (2) adequate opportunity for sleep, and (3) associated daytime dysfunction.5

How insomnia affects specific patient populations

Children and adolescents. Appropriate screening, diagnosis, and interventions for insomnia in children and adolescents are associated with better health outcomes, including improved attention, behavior, learning, memory, emotional regulation, quality of life, and mental and physical health.6 In one study of insomnia in the pediatric population (N = 1038), 41% of parents reported symptoms of sleep disturbances in their children.7 Pediatric insomnia can lead to impaired attention, poor academic performance, and behavioral disturbances.7 In addition, there is a high prevalence of sleep disturbances in children with neurodevelopmental disorders.8

Insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder in adolescents but frequently goes unrecognized, and therefore is underdiagnosed and undertreated.9 Insomnia in adolescents is associated with depression and suicidality.9-12 Growing evidence also links it to anorexia nervosa,13 substance use disorders,14 and impaired neurocognitive function.15

Continue to: Pregnant women

Pregnant women. Sleep disorders in pregnancy are common and influenced by multiple factors. A meta-analysis found that 57% to 74% of women in various trimesters of pregnancy reported subthreshold symptoms of insomnia16; however, changes in sleep duration and sleep quality during pregnancy may be related to hormonal, physiologic, metabolic, psychological, and posture mechanisms.17,18

Sleep quality also worsens as pregnancy progresses.16 Insomnia coupled with poor sleep quality has been shown to increase the risk for postpartum depression, premature delivery, prolonged labor, and cesarean delivery, as well as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, stillbirth, and large-for-gestational-age infants.19,20

Older adults. Insomnia is a common complaint in the geriatric population and is associated with significant morbidity, as well as higher rates of depression and suicidality.21 Circadian rhythms change and sleep cycles advance as people age, leading to a decrease in total sleep time, earlier sleep onset, earlier awakenings,and increased frequency of waking after sleep onset.21,22 Advanced age, polypharmacy, and high medical comorbidity increase insomnia prevalence.23

Studies have shown that older adults who sleep fewer than 5 hours per night have an increased risk for diabetes and metabolic syndrome.21 Sleep loss also has been linked to increased rates of hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and possibly stroke.21,22 Poor sleep has been associated with increased rates of cortical atrophy in community-dwelling older adults.21 Daytime drowsiness increases fall risk.22 Older adults with self-reported decreased physical function also had increased rates of insomnia and increased rates of daytime sleepiness.22

Making the diagnosis: What to ask, tools to use

Clinical evaluation is most helpful for diagnosing insomnia.24 A complete work-up includes physical examination, review of medications and supplements, evaluation of a 2-week sleep diary (kept by the patient, parent, or caregiver), and assessment using a validated sleep-quality rating scale.24 Be sure to obtain a complete health history, including medical events, substance use, and psychiatric history.24

Continue to: Inquire about sleep initiation...

Inquire about sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, and early awakening, as well as behavioral and environmental factors that may contribute to sleep concerns.10,18 Consider medical sleep disorders that have overlapping symptoms with insomnia, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), restless leg syndrome (RLS), or circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders. If there are co-occurring chronic medical problems, reassess insomnia symptoms after the other medical diagnoses are controlled.

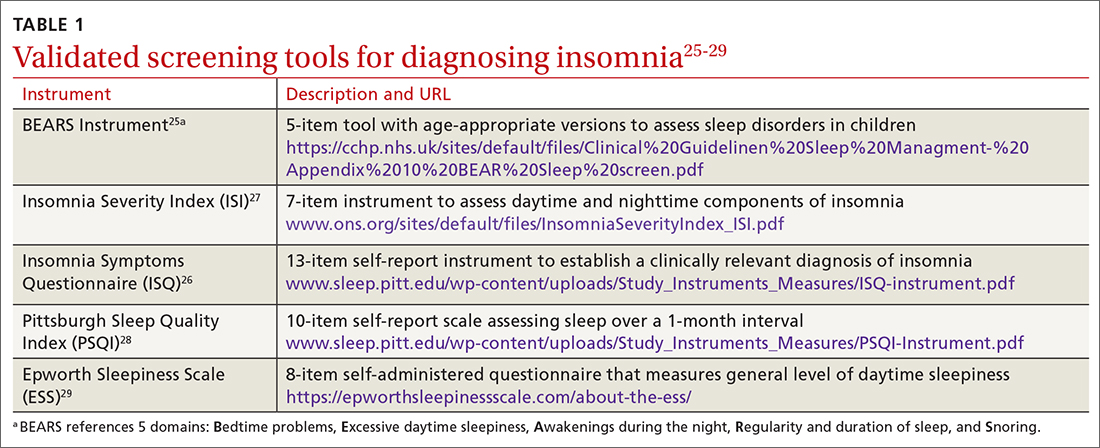

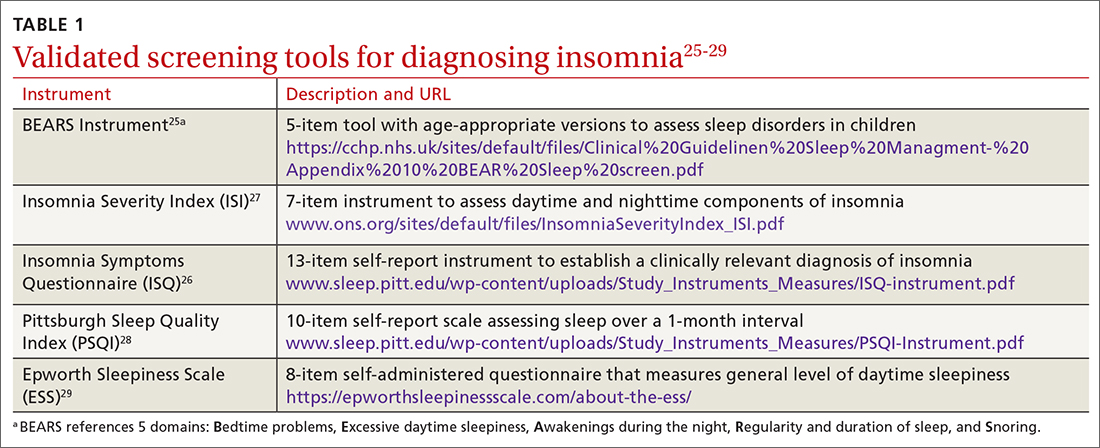

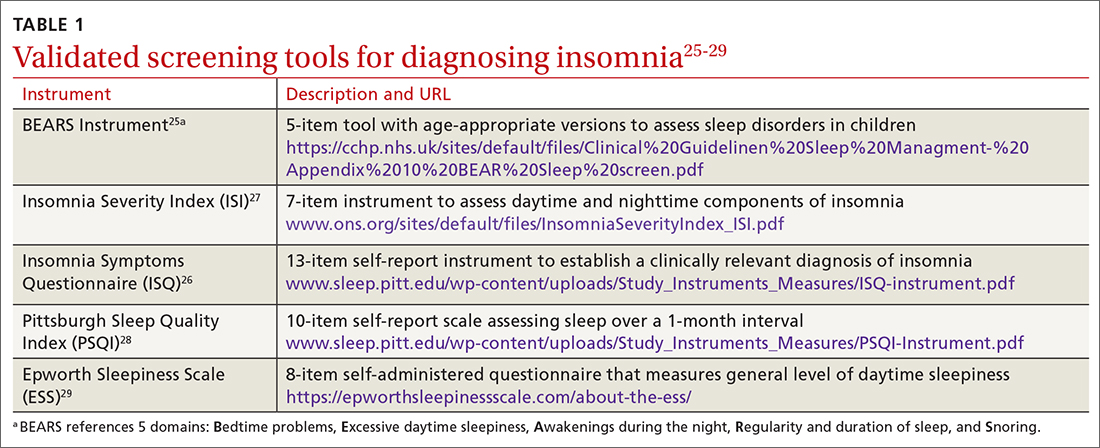

TABLE 125-29 includes a list of validated screening tools for insomnia and where they can be accessed. Recommended screening tools for children and adolescents include daytime sleepiness questionnaires, comprehensive sleep instruments, and self-assessments.25,30 Although several studies of insomnia in pregnancy have used tools listed in TABLE 1,25-29 only the Insomnia Severity Index has been validated for use with this population.26,27 Diagnosis of insomnia in older adults requires a comprehensive sleep history collected from the patient, partners, or caregivers.21

Measuring sleep performance

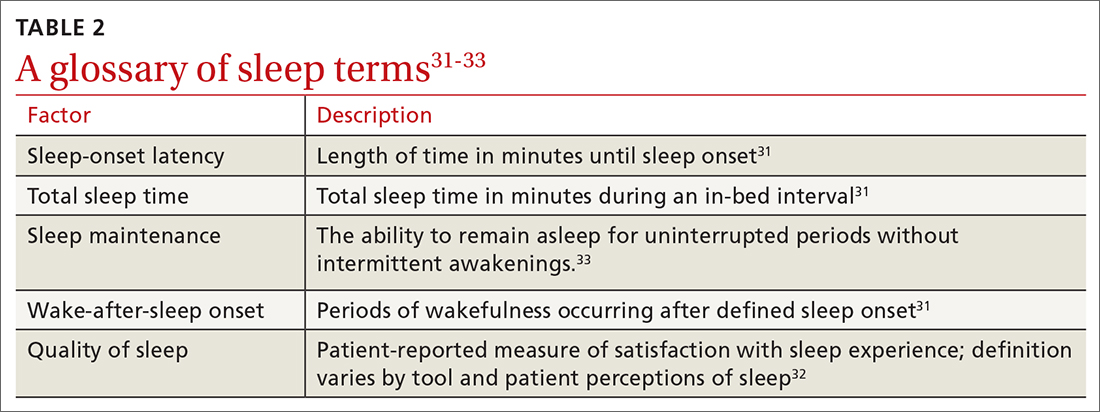

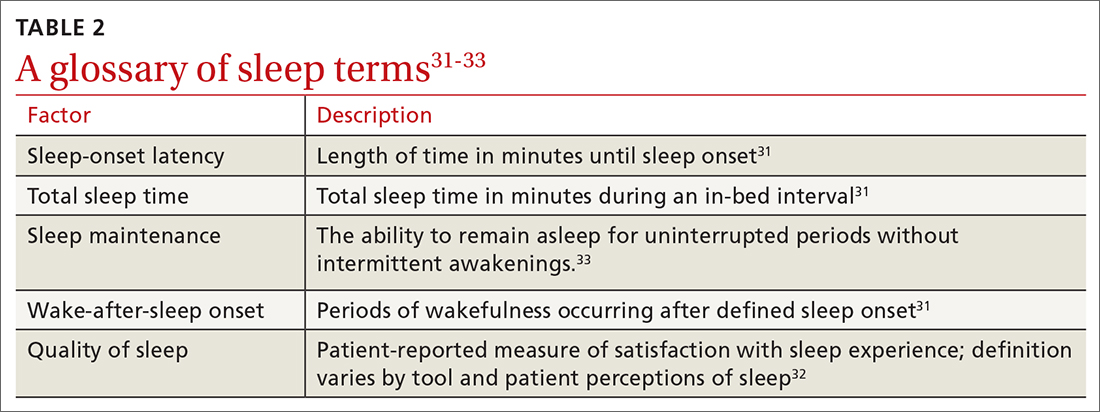

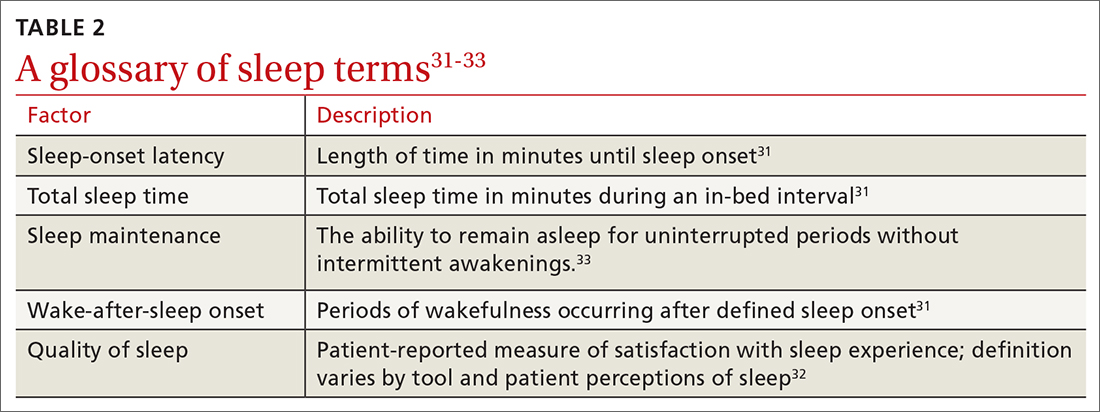

Several aspects of insomnia (defined in TABLE 231-33) are targeted as outcome measures when treating patients. Sleep-onset latency, total sleep time, and wake-after-sleep onset are all formally measured by polysomnography.31-33 Use polysomnography when you suspect OSA, narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, periodic limb movement disorder, RLS, REM behavior disorder (characterized by the loss of normal muscle atonia and dream enactment behavior that is violent in nature34), or parasomnias. Home polysomnography testing is appropriate for adult patients who meet criteria for OSA and have uncomplicated insomnia.35 Self-reporting (use of sleep logs) and actigraphy (measurement by wearable monitoring devices) may be more accessible methods for gathering sleep data from patients. Use of wearable consumer sleep technology such as heart rate monitors with corresponding smartphone applications (eg, Fitbit, Jawbone Up devices, and the Whoop device) are increasing as a means of monitoring sleep as well as delivering insomnia interventions.36

Actigraphy has been shown to produce significantly distinct results from self-reporting when measuring total sleep time, sleep-onset latency, wake-after-sleep onset, and sleep efficiency in adult and pediatric patients with insomnia.37 Actigraphy yields distinct estimates of sleep patterns when compared to sleep logs, which suggests that while both measures are often correlated, actigraphy has utility in assessing sleep continuity in conjunction with sleep logs in terms of diagnostic and posttreatment assessment.37

Continue to: Treatment options

Treatment options: Start with the nonpharmacologic

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are available for the treatment of insomnia. Starting with nonpharmacologic options is preferred.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

Sleep hygiene. Poor sleep hygiene can contribute to insomnia but does not cause it.31 Healthy sleep habits include keeping the sleep environment quiet, free of interruptions, and at an adequate temperature; adhering to a regular sleep schedule; avoiding naps; going to bed when drowsy; getting out of bed if not asleep within 15 to 20 minutes and returning when drowsy; exercising regularly; and avoiding caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and other substances that interfere with sleep.24 Technology use prior to bedtime is prevalent and associated with sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances.38

Sleep hygiene education is often insufficient on its own.31 But it has been shown to benefit older adults with insomnia.19,32

Sleep hygiene during pregnancy emphasizes drinking fluids only in the daytime to avoid awakening to urinate at night, avoiding specific foods to decrease heartburn, napping only in the early part of the day, and sleeping on either the left or the right side of the body with knees and hips bent and a pillow under pressure points in the second and third trimesters.18,39

Pediatric insomnia. Sleep hygiene is an important first-line treatment for pediatric insomnia, especially among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.40

Continue to: CBT-I

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). US and European guidelines recommend CBT-I—a multicomponent, nonpharmacologic, insomnia-focused psychotherapy—as a first-line treatment for short- and long-term insomnia32,41,42 across a wide range of patient demographics.17,43-47 CBT-I is a multiweek intensive treatment that combines sleep hygiene practices with cognitive therapy and behavioral interventions, including stimulus control, sleep restriction, and relaxation training.32,48 CBT-I monotherapy has been shown to have greater efficacy than sleep hygiene education for patients with insomnia, especially for those with medical or psychiatric comorbidities.49 It also has been shown to be effective when delivered in person or even digitally.50-52 For example, CBT-I Coach is a mobile application for people who are already engaged in CBT-I with a health care provider; it provides a structured program to alleviate symptoms.53

Although CBT-I methods are appropriate for adolescents and school-aged children, evaluations of the efficacy of the individual components (stimulus control, arousal reduction, cognitive therapy, improved sleep hygiene practices, and sleep restriction) are needed to understand what methods are most effective in this population.9

Cognitive and/or behavioral Interventions. Cognitive therapy (to change negative thoughts about sleep) and behavioral interventions (eg, changes to sleep routines, sleep restriction, moving the child’s bedtime to match the time of falling asleep [bedtime fading],41 stimulus control)9,43,54-56 may be used independently. Separate meta-analyses support the use of cognitive and behavioral interventions for adolescent insomnia,9,43 school-aged children with insomnia and sleep difficulties,43,49 and adolescents with sleep difficulties and daytime fatigue.41 The trials for children and adolescents followed the same recommendations for treatment as CBT-I but often used fewer components of the treatment, resulting in focused cognitive or behavioral interventions.

One controlled evaluation showed support for separate cognitive and behavioral techniques for insomnia in children.54 A meta-analysis (6 studies; N = 529) found that total sleep time, as measured with actigraphy, improved among school-aged children and adolescents with insomnia after treatment with 4 or more types of cognitive or behavioral therapy sessions.43 Sleep-onset latency, measured by actigraphy and sleep diaries, decreased in the intervention group.43

A controlled evaluation of CBT for behavioral insomnia in school-aged children (N = 42) randomized participants to CBT (n = 21) or waitlist control (n = 21).54 The 6 CBT sessions combined behavioral sleep medicine techniques (ie, sleep restriction) with anxiety treatment techniques (eg, cognitive restructuring).54 Those in the intervention group showed statistically significant improvement in sleep latency, wake-after-sleep onset, and sleep efficiency (all P ≤ .003), compared with controls.54 Total sleep time was unaffected by the intervention. A notable change was the number of patients who still had an insomnia diagnosis postintervention. Among children in the CBT group, 14.3% met diagnostic criteria vs 95% of children in the control group.54 Similarly, at the 1-month follow-up, 9.5% of CBT group members still had insomnia, compared with 86.7% of the control group participants.54

Continue to: Multiple randomized and nonranomized studies...

Multiple randomized and nonrandomized studies have found that infants also respond to behavioral interventions, such as establishing regular daytime and sleep routines, reducing environmental noises or distractions, and allowing for self-soothing at bedtime.55 A controlled trial (N = 279) of newborns and their mothers evaluated sleep interventions that included guidance on bedtime sleep routines, starting the routine 30 to 45 minutes before bedtime, choosing age-appropriate calming bedtime activities, not using feeding as the last step before bedtime, and offering the child choices with their routine.56 The intervention group demonstrated longer sleep duration (624.6 ± 67.6 minutes vs 602.9 ± 76.1 minutes; P = .01) at 40 weeks postintervention compared with the control group.56

The clinically significant outcomes of this study are related to the guidance offered to parents to help infants achieve longer sleep. More intervention-group infants were allowed to self-soothe to sleep without being held or fed, had earlier bedtimes, and fell asleep ≤ 15 minutes after being put into bed than their counterparts in the control group.56

Exercise. As a sole intervention, exercise for insomnia is readily available and low cost, but it is not universally effective. One study of patients older than 60 years (N = 43) showed that a 16-week moderate exercise regimen slightly improved total sleep time by an average of 42 minutes (P = .05), sleep-onset latency improved an average of 11.5 minutes (P = .007), and global sleep quality improved by 3.4 points as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; P ≤ .01).57 No significant improvements occurred in sleep efficiency. Exercise is one of several nonpharmacologic alternatives for treating insomnia in pregnancy.58

A lack of uniformity in patient populations, intervention protocols, and outcome measures confounded results of 2 systematic reviews that included comparisons of yoga or tai chi as standalone alternatives to CBT-I for insomnia treatment.58,59 Other interventions, such as mindfulness or relaxation training, have been studied as insomnia interventions, but no conclusive evidence about their efficacy exists.45,59

Pharmacologic interventions

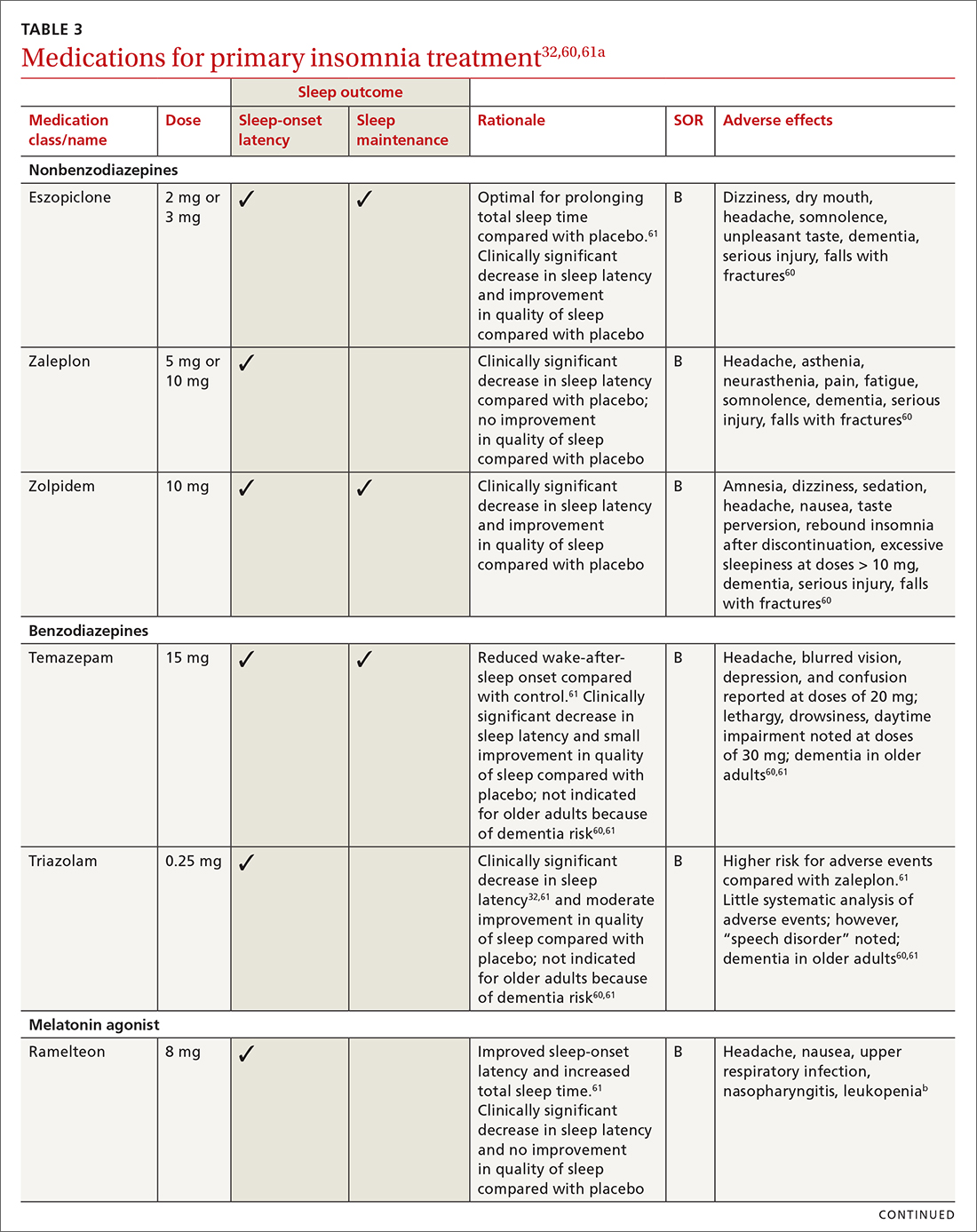

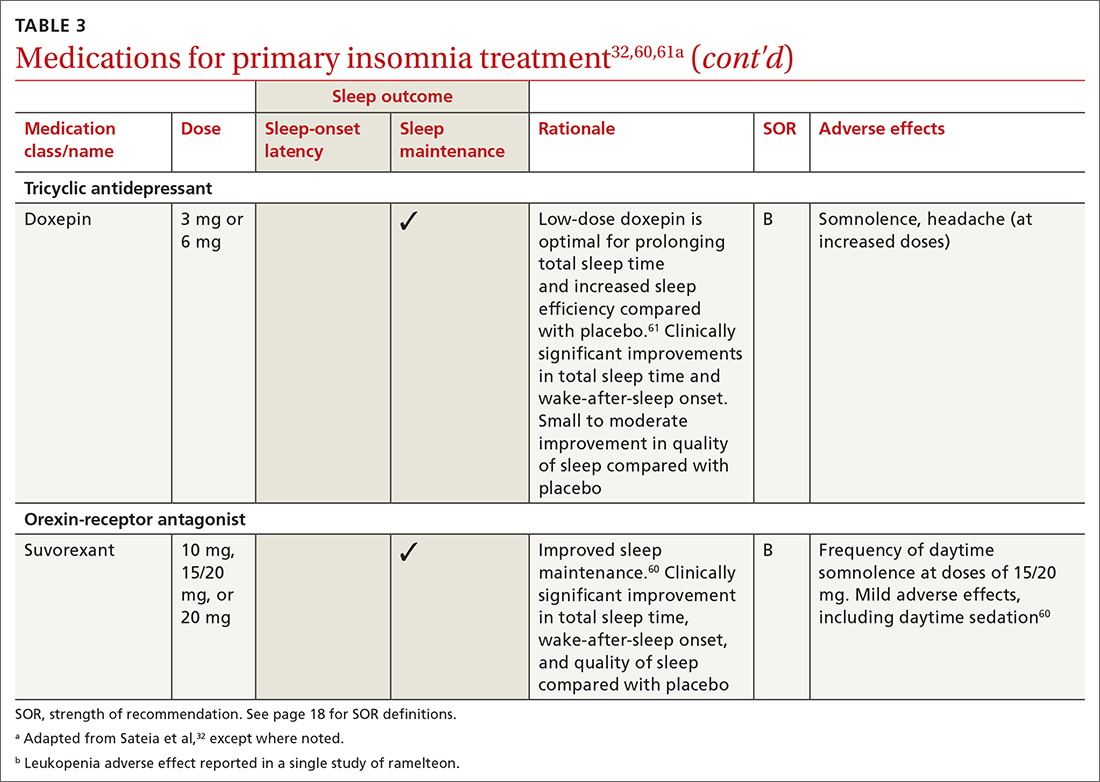

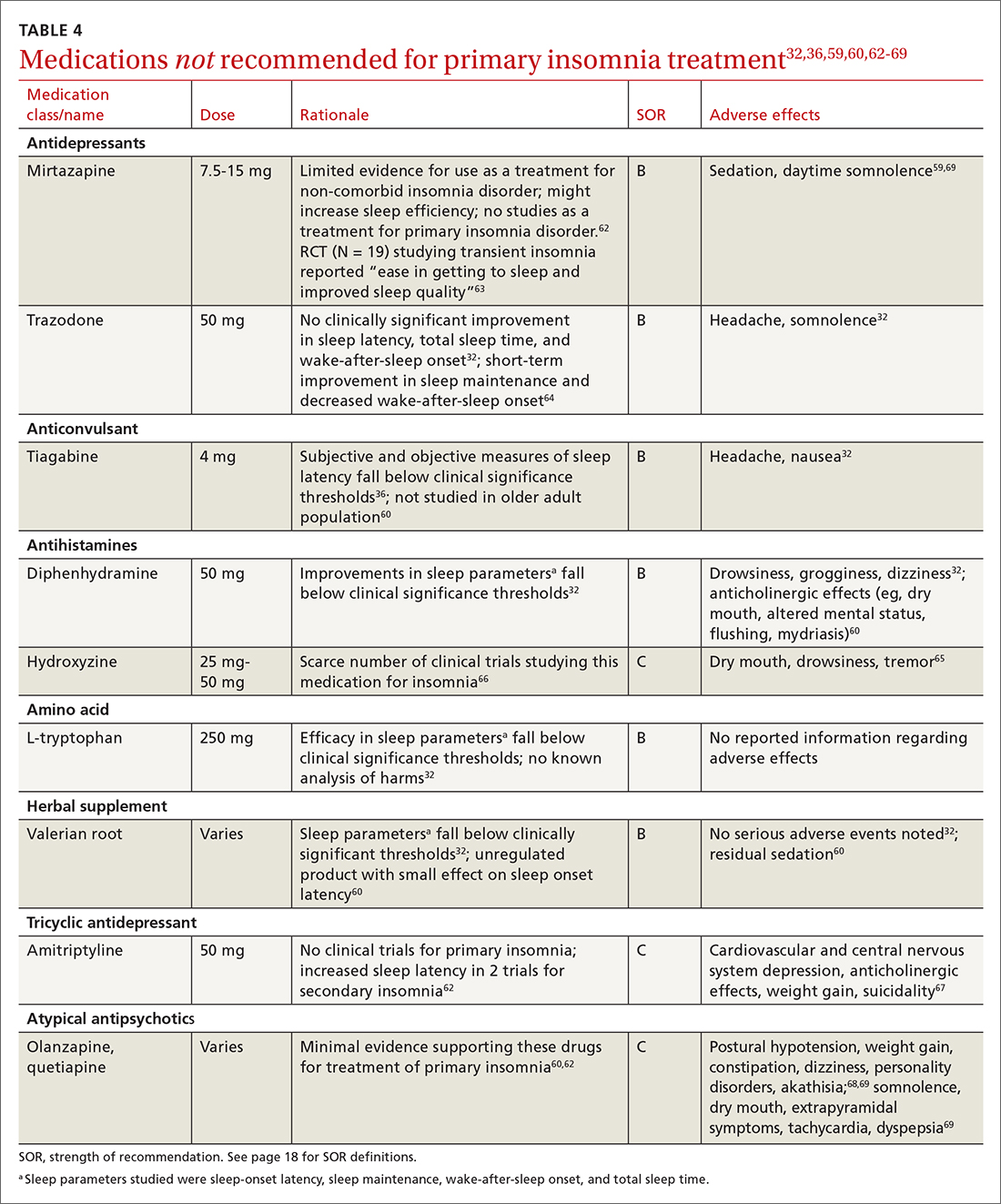

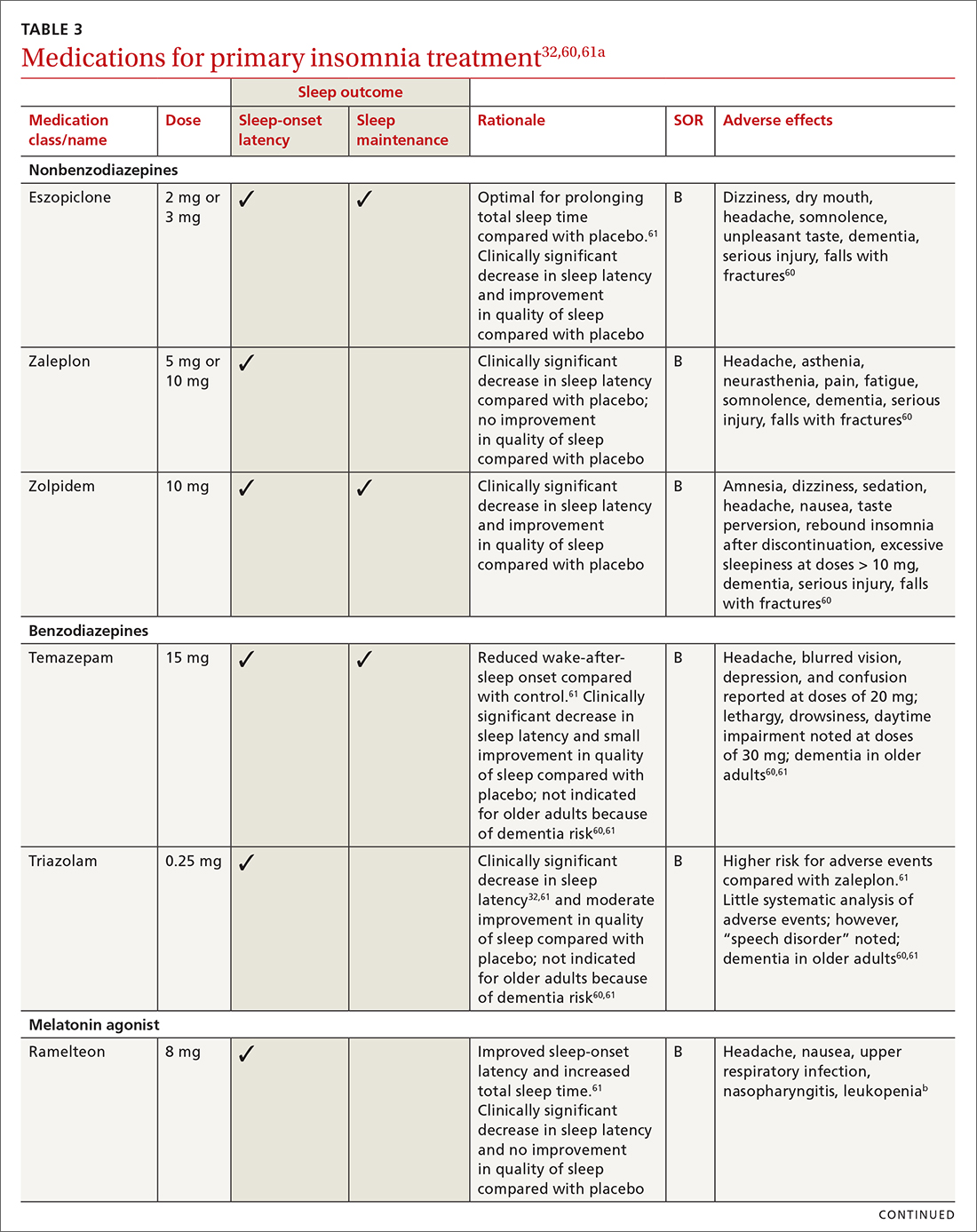

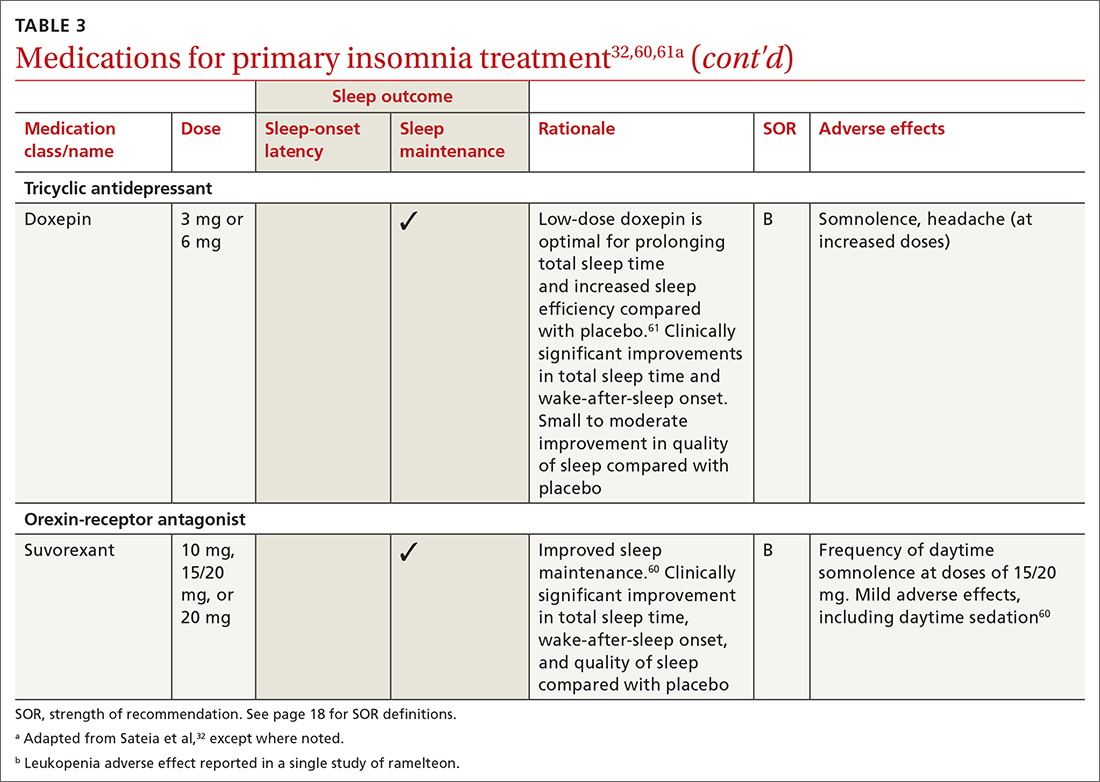

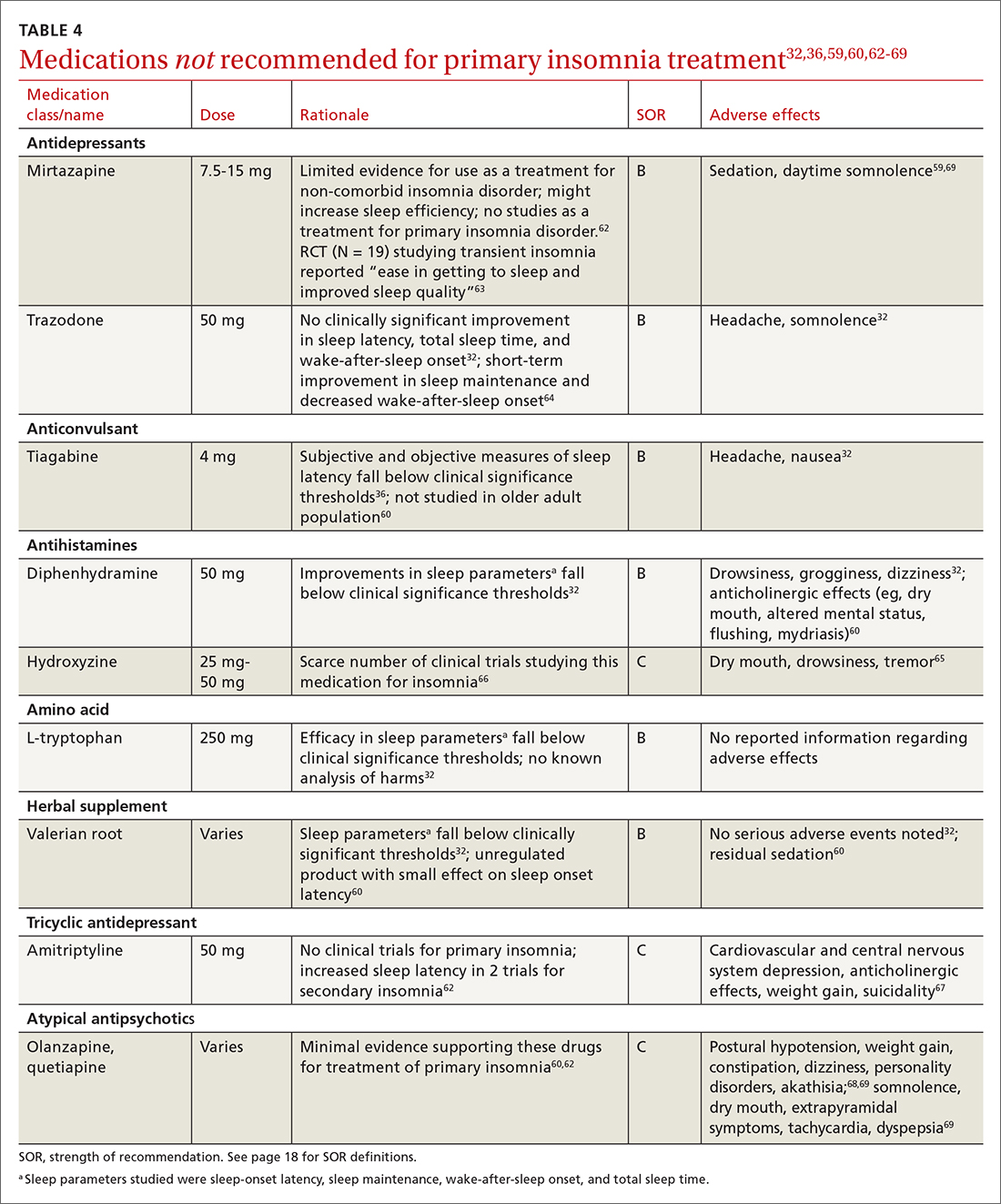

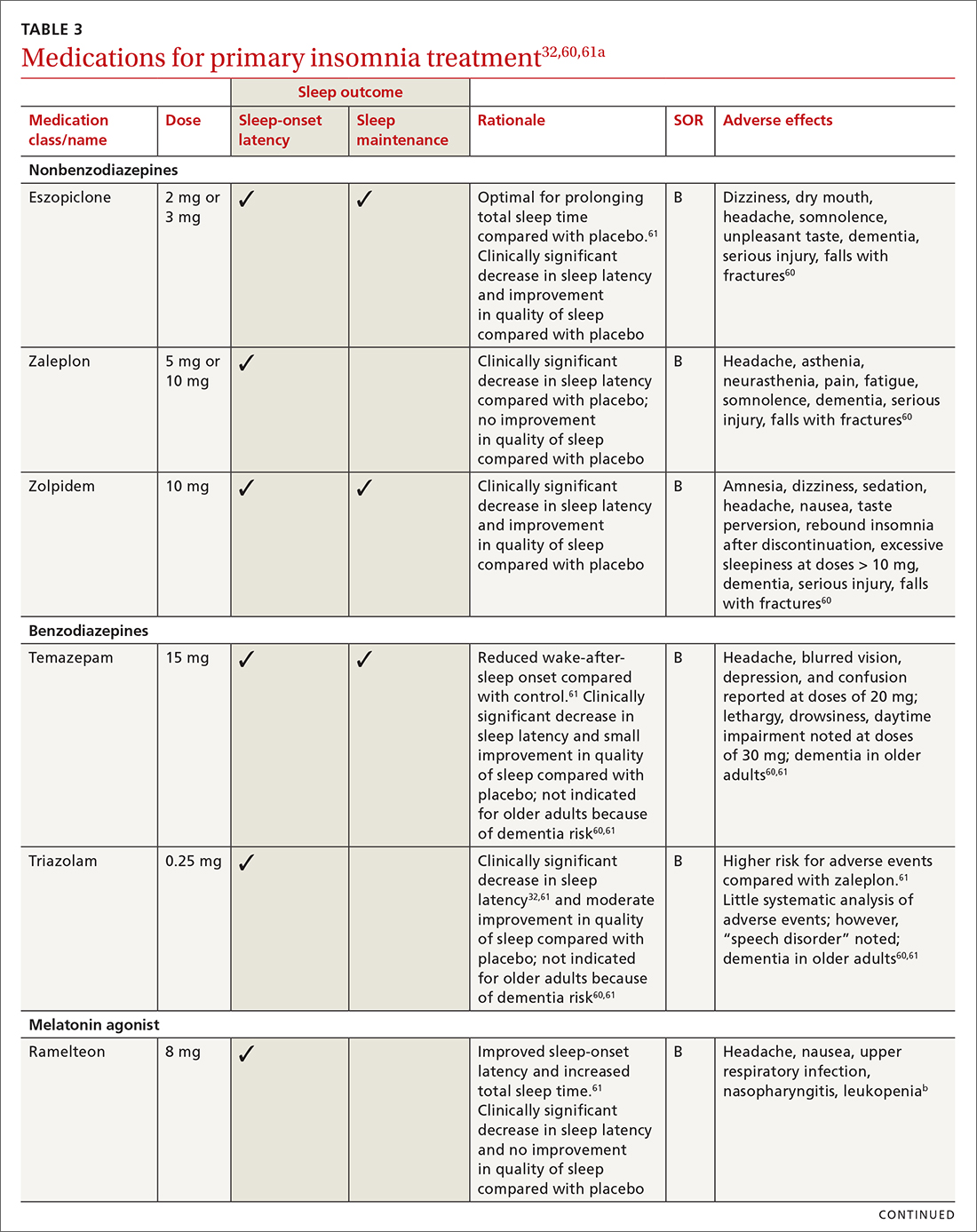

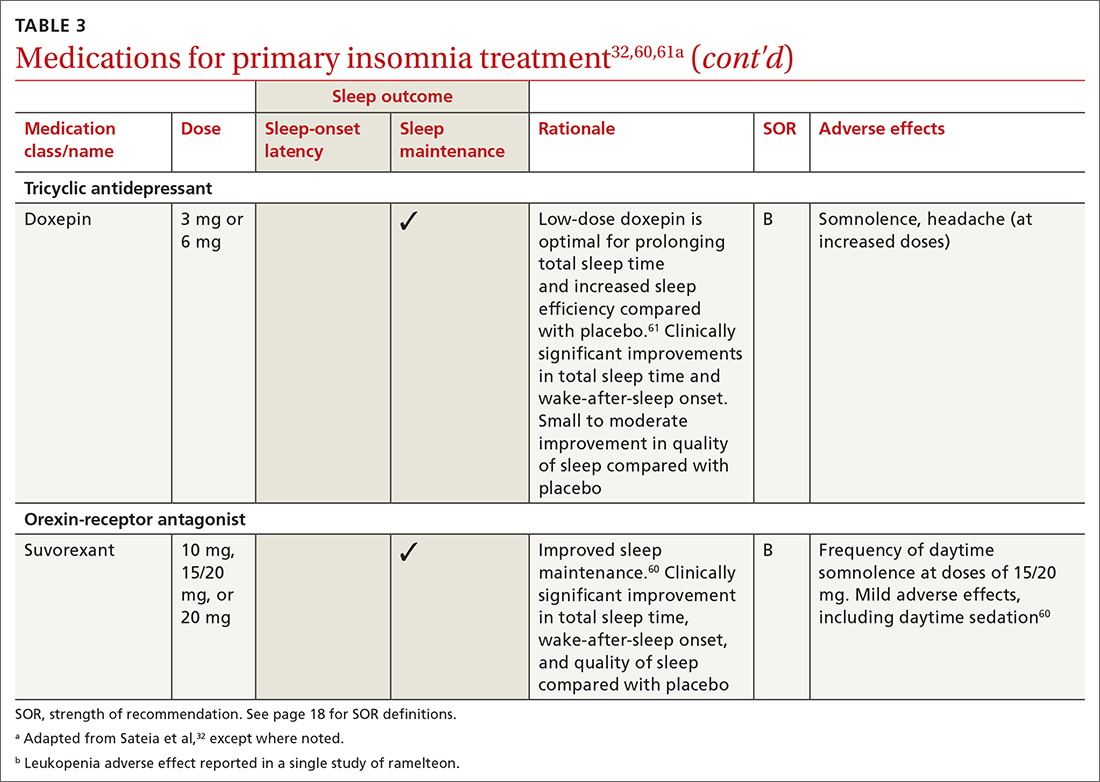

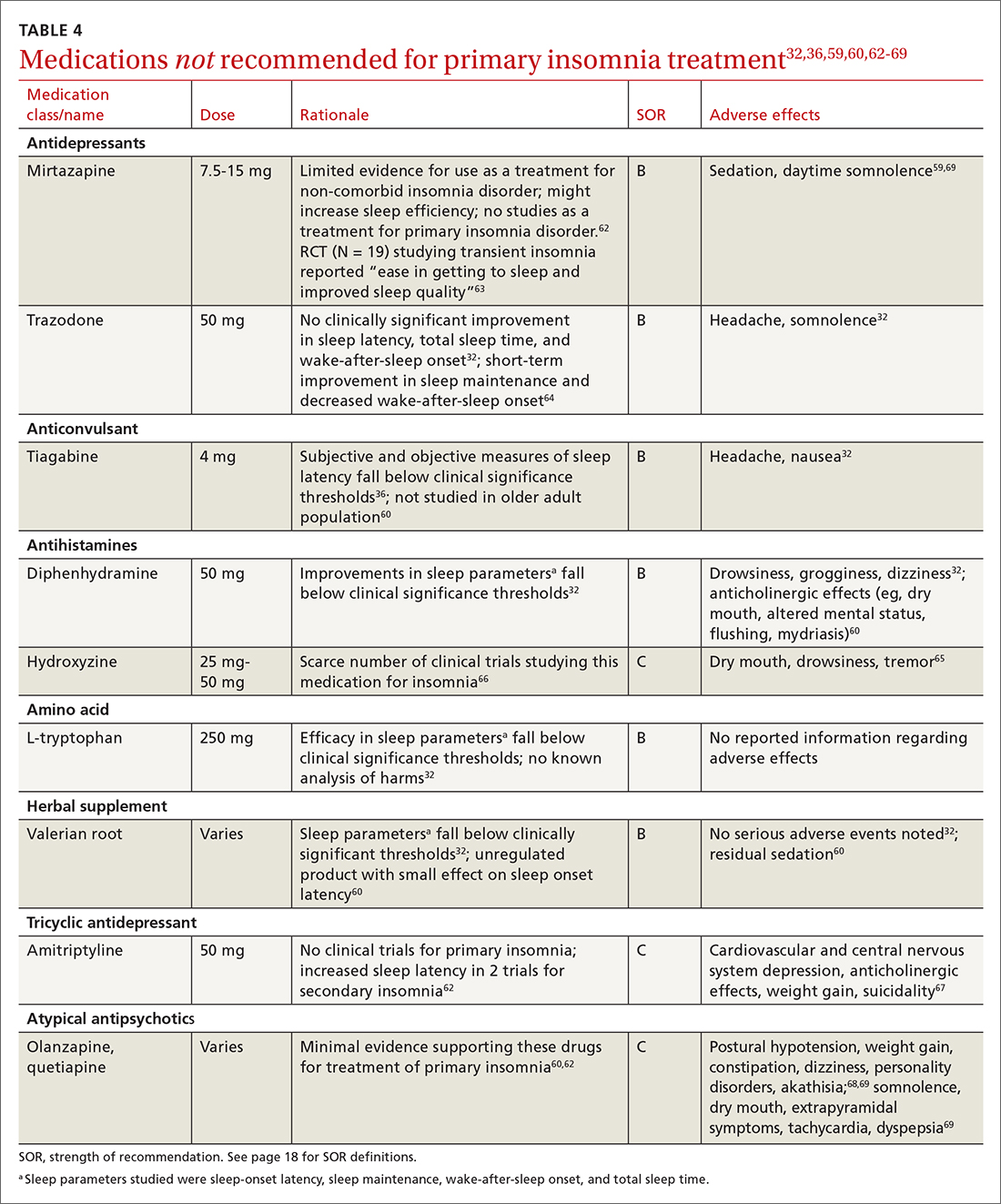

Pharmacologic treatment should not be the sole intervention for the treatment of insomnia but should be used in combination with nonpharmacologic interventions.32 Of note, only low-quality evidence exists for any pharmacologic interventions for insomnia.32 The decision to prescribe medications should rely on the predominant sleep complaint, with sleep maintenance and sleep-onset latency as the guiding factors.32 Medications used for insomnia treatment (TABLE 332,60,61)are classified according to these and other sleep outcomes described in TABLE 1.25-29 Prescribe them at the lowest dose and for the shortest amount of time possible.32,62 Avoid medications listed in TABLE 432,36,59,60,62-69 because data showing clinically significant improvements in insomnia are lacking, and analysis for potential harms is inadequate.32

Continue to: Melatonin is not recommended

Melatonin is not recommended for treating insomnia in adults, pregnant patients, older adults, or most children because its effects are clinically insignificant,32 residual sedation has been reported,60 and no analysis of harms has been undertaken.32 Despite this, melatonin is frequently utilized for insomnia, and patients take over-the-counter melatonin for a myriad of sleep complaints. Melatonin is indicated in the treatment of insomnia in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. (See discussion in "Prescribing for children.")

Hypnotics are medications licensed for short-term sleep promotion in adults and can induce tolerance and dependence.32 Nonbenzodiazepine-receptor agonists at clinical doses do not appear to suppress REM sleep, although there are reports of increases in latency to REM sleep.70

Antidepressants. Although treatment of insomnia with antidepressants is widespread, evidence of their efficacy is unclear.32,62 The tolerability and safety of antidepressants for insomnia also are uncertain due to limited reporting of adverse events.32

The use of sedating antidepressants may be driven by concern over the longer-term use of hypnotics and the limited availability of psychological treatments including CBT-I.32 Sedating antidepressants are indicated for comorbid or secondary insomnia (attributable to mental health conditions, medical conditions, other sleep disorders, or substance use or misuse); however, there are few clinical trials studying them for primary insomnia treatment.62 Antidepressants—tricyclic antidepressants included—can reduce the amount of REM sleep and increase REM sleep-onset latency.71,72

Antihistamines and antipsychotics. Although antihistamines (eg, hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine) and antipsychotics frequently are prescribed off-label for primary insomnia, there is a lack of evidence to support either type of medication for this purpose.36,62,73 H1-antihistamines such as hydroxyzine increase REM-onset latency and reduce the duration of REM sleep.73 Depending on the specific medication, second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine and quetiapine have mixed effects on REM sleep parameters.65

Continue to: Prescribing for children

Prescribing for children. There is no FDA-approved medication for the treatment of insomnia in children.52 However, melatonin has shown promising results for treating insomnia in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. A systematic review (13 trials; N = 682) with meta-analysis (9 studies; n = 541) showed that melatonin significantly improved total sleep time compared with placebo (mean difference [MD] = 48.26 minutes; 95% CI, 36.78-59.73).8 In 11 studies (n = 581), sleep-onset latency improved significantly with melatonin use.8 No difference was noted in the frequency of wake-after-sleep onset.8 No medication-related adverse events were reported. Heterogeneity (I2 = 31%) and inconsistency among included studies shed doubt on the findings; therefore, further research is needed.8

Prescribing in pregnancy. Prescribing medications to treat insomnia in pregnancy is complex and controversial. No consistency exists among guidelines and recommendations for treating insomnia in the pregnant population. Pharmacotherapy for insomnia is frequently prescribed off-label in pregnant patients. Examples include benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, antidepressants, and gamma-aminobutyric acid–reuptake inhibitors.45

Pharmacotherapy in pregnancy is a unique challenge, wherein clinicians consider not only the potential drug toxicity to the fetus but also the potential changes in the pregnant patient’s pharmacokinetics that influence appropriate medication doses.39,74 Worth noting: Zolpidem has been associated with preterm birth, cesarean birth, and low-birth-weight infants.45,74 The lack of clinical trials of pharmacotherapy in pregnant patients results in a limited understanding of medication effects on long-term health and safety outcomes in this population.39,74

A review of 3 studies with small sample sizes found that when antidepressants or antihistamines were taken during pregnancy, neither had significant adverse effects on mother or child.68 Weigh the risks of medications with the risk for disease burden and apply a shared decision-making approach with the patient, including providing an accurate assessment of risks and safety information regarding medication use.39 Online resources such as ReproTox (www.reprotox.org) and MotherToBaby (https://mothertobaby.org) are available to support clinicians treating pregnant and lactating patients.39

Prescribing for older adults. Treatment of insomnia in older adults requires a multifactorial approach.22 For all older adults, start interventions with nonpharmacologic treatments for insomnia followed by treatment of any underlying medical and psychiatric disorders that affect sleep.21 If medications are required, start with the lowest dose and titrate upward slowly. Use sedating low-dose antidepressants for insomnia only when the older patient has comorbid depression.60 Although nonbenzodiazepine-receptor agonists have improved safety profiles compared with benzodiazepines, their use for older adults should be limited because of adverse effects that include dementia, serious injury, and falls with fractures.60

Keep these points in mind

Poor sleep has many detrimental health effects and can significantly affect quality of life for patients across the lifespan. Use nonpharmacologic interventions—such as sleep hygiene education, CBT-I, and cognitive/behavioral therapies—as first-line treatments. When utilizing pharmacotherapy for insomnia, consider the patient’s distressing symptoms of insomnia as guideposts for prescribing. Use pharmacologic treatments intermittently, short term, and in conjunction with nonpharmacologic options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Angela L. Colistra, PhD, LPC, CAADC, CCS, 707 Hamilton Street, 8th floor, LVHN Department of Family Medicine, Allentown, PA 18101; angela.colistra@lvhn.org

1. Roth T, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, et al. Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition criteria: results from the America Insomnia Survey. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:592-600. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.023

2. DiBonaventura M, Richard L, Kumar M, et al. The association between insomnia and insomnia treatment side effects on health Status, work productivity, and healthcare resource use. PloS One. 2015;10:e0137117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137117

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013: 362-368.

4. Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders—third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014;146:1387-1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0970

5. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 3d ed; 2014.

6. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:785-786. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5866

7. Archbold KH, Pituch KJ, Panahi P, et al. Symptoms of sleep disturbances among children at two general pediatric clinics. J Pediatr. 2002;140:97-102. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.119990

8. Abdelgadir IS, Gordon MA, Akobeng AK. Melatonin for the management of sleep problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:1155-1162. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314181

9. de Zambotti M, Goldstone A, Colrain IM, et al. Insomnia disorder in adolescence: diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:12-24. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.009

10. Roberts RE, Duong HT. Depression and insomnia among adolescents: a prospective perspective. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:66-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.049

11. Sivertsen B, Harvey AG, Lundervold AJ, et al. Sleep problems and depression in adolescence: results from a large population-based study of Norwegian adolescents aged 16-18 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:681-689. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0502-y

12. Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK, et al. The direction of the relationship between symptoms of insomnia and psychiatric disorders in adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:167-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.032

13. Allison KC, Spaeth A, Hopkins CM. Sleep and eating disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18:92. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0728-8

14. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future: National Results on Drug Use: 1975-2013. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014.

15. Kuula L, Pesonen AK, Martikainen S, et al. Poor sleep and neurocognitive function in early adolescence. Sleep Med. 2015;16:1207-1212. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.06.017

16. Sedov ID, Anderson NJ, Dhillon AK. Insomnia symptoms during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2021;30:e13207. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13207

17. Oyiengo D, Louis M, Hott B, et al. Sleep disorders in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35:571-587. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.06.012

18. Hashmi AM, Bhatia SK, Bhatia SK, et al. Insomnia during pregnancy: diagnosis and rational interventions. Pak J Med Sci. 2016; 32:1030-1037. doi: 10.12669/pjms.324.10421

19. Abbott SM, Attarian H, Zee PC. Sleep disorders in perinatal women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:159-168. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.003

20. Lu Q, Zhang X, Wang Y, et al. Sleep disturbances during pregnancy and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;58:101436. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101436

21. Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P. Insomnia in the elderly: a review. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14:1017-1024. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7172

22. Miner B, Kryger MH. Sleep in the aging population. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12:31-38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.008

23. Miner B, Gill TM, Yaggi HK, et al. Insomnia in community-living persons with advanced age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1592-1597. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15414

24. Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:487-504.

25. Owens JA, Dalzell V. Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2005;6:63-69. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.07.015

26. Okun ML, Buysse DJ, Hall MH. Identifying insomnia in early pregnancy: validation of the Insomnia Symptoms Questionnaire (ISQ) in pregnant women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:645-54. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4776

27. Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601-608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601

28. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

29. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540-545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540

30. Baddam SKR, Canapari CA, Van de Grift J, et al. Screening and evaluation of sleep disturbances and sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2021;30:65-84. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2020.09.005

31. De Crescenzo F, Foti F, Ciabattini M, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological treatments for insomnia in adults: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(9):CD012364. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012364

32. Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:307-349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470

33. Morin AK, Jarvis CI, Lynch AM. Therapeutic options for sleep-maintenance and sleep-onset insomnia. Pharmacother. 2007; 27:89-110. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.1.89

34. Berry RB, Wagner MH. Sleep Medicine Pearls. 3rd ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:533-541.

35. Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:479-504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6506

36. Glazer Baron K, Culnan E, Duffecy J, et al. How are consumer sleep technology data being used to deliver behavioral sleep medicine interventions? A systematic review. Behav Sleep Med. 2022;20:173-187. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2021.1898397

37. Smith MT, McCrae CS, Cheung J, et al. Use of actigraphy for the evaluation of sleep disorders and circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE assessment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14:1209-1230.

38. Gradisar M, Wolfson AR, Harvey AG, et al. The sleep and technology use of Americans: findings from the National Sleep Foundation’s 2011 Sleep in America poll. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:1291-1299. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3272

39. Miller MA, Mehta N, Clark-Bilodeau C, et al. Sleep pharmacotherapy for common sleep disorders in pregnancy and lactation. Chest. 2020;157:184-197. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.09.026

40. Nikles J, Mitchell GK, de Miranda Araújo R, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of sleep hygiene in children with ADHD. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25:497-518. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1732431

41. Baglioni C, Altena E, Bjorvatn B, et al. The European Academy for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia: an initiative of the European Insomnia Network to promote implementation and dissemination of treatment. J Sleep Res. 2019;29. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12967

42. Jernelöv S, Blom K, Hentati Isacsson N, et al. Very long-term outcome of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: one- and ten-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2022;51:72-88. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2021.2009019

43. Åslund L, Arnberg F, Kanstrup M, et al. Cognitive and behavioral interventions to improve sleep in school-age children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14:1937-1947. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7498

44. Manber R, Bei B, Simpson N, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for prenatal insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:911-919. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003216

45. Bacaro V, Benz F, Pappaccogli A, et al. Interventions for sleep problems during pregnancy: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;50:101234. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101234

46. Hinrichsen GA, Leipzig RM. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in geriatric primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2993-2995. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17319

47. Sadler P, McLaren S, Klein B, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with insomnia and depression: a randomized controlled trial in community mental health services. Sleep. 2018;41:1-12. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy104

48. American Sleep Association. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): treatment for insomnia. Accessed May 4, 2022. www.sleepassociation.org/sleep-treatments/cognitive-behavioral-therapy/#:~:text=Cognitive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Insomnia%2C%20also%20known%20as

49. Zhou FC, Yang Y, Wang YY, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia monotherapy in patients with medical or psychiatric comorbidities: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Q. 2020;91:1209-1224. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09820-8

50. Cheng P, Luik AI, Fellman-Couture C, et al. Efficacy of digital CBT for insomnia to reduce depression across demographic groups: a randomized trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49:491-500. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001113

51. Felder JN, Epel ES, Neuhaus J, et al. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia symptoms among pregnant women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psych. 2020;77:484-492. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4491

52. de Bruin EJ, Bögels SM, Oort FJ, et al. Improvements of adolescent psychopathology after insomnia treatment: results from a randomized controlled trial over 1 year. J Child Psychol Psych. 2018;59:509-522. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12834

53. Hoffman JE, Taylor K, Manber R, et al. CBT-I Coach (version 1.0). [Mobile application software]. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://itunes.apple.com

54. Paine S, Gradisar M. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behaviour therapy for behavioural insomnia of childhood in school-aged children. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:379-88. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.008

55. Hungenberg M, Houss B, Narayan M, et al. Do behavioral interventions improve nighttime sleep in children < 1 year old? J Fam Pract. 2022;71:E16-E17. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0446

56. Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. INSIGHT Responsive Parenting Intervention and Infant Sleep. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160762. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0762

57. Montgomery P, Dennis J. Physical exercise for sleep problems in adults aged 60+. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; 2002(4):CD003404. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003404

58. Yang SY, Lan SJ, Yen YY, et al. Effects of exercise on sleep quality in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2020;14:1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2020.01.003

59. Wang F, Eun-Kyoung Lee O, Feng F, et al. The effect of meditative movement on sleep quality: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;30:43-52. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.12.001

60. Schroeck JL, Ford J, Conway EL, et al. Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medicines in older adults. Clin Ther. 2016;38:2340-2372. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.09.010

61. Chiu HY, Lee HC, Liu JW, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of hypnotics for insomnia in older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep. 2021;44(5):zsaa260. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa260

62. Atkin T, Comai S, Gobbi G. Drugs for insomnia beyond benzodiazepines: pharmacology, clinical applications, and discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70:197-245. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.014381

63. Karsten J, Hagenauw LA, Kamphuis J, et al. Low doses of mirtazapine or quetiapine for transient insomnia: a randomised, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:327-337. doi: 10.1177/0269881116681399

64. Yi X-Y, Ni S-F, Ghadami MR, et al. Trazodone for the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2018;45:25-32. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.01.010

65. Monti JM, Torterolo P, Pandi Perumal SR. The effects of second generation antipsychotic drugs on sleep variables in healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;33:51-57. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.05.002

66. Krzystanek M, Krysta K, Pałasz A. First generation antihistaminic drugs used in the treatment of insomnia—superstitions and evidence. Pharmacother Psychiatry Neurol. 2020;36:33-40.

67. Amitriptyline hydrochloride. NIH US National Library of Medicine: DailyMed. Updated October 6, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=a4d012a4-cd95-46c6-a6b7-b15d6fd5269d

68. Olanzapine. NIH US National Library of Medicine: DailyMed. Updated October 23, 2015. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=e8626e68-088d-47ff-bf06-489a778815aa

69. Quetiapine extended release. NIH US National Library of Medicine: DailyMed. Updated January 28, 2021. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=07e4f3f4-42cb-4b22-bf8d-8c3279d26e9

70. Roehrs T, Roth T. Drug-related sleep stage changes: functional significance and clinical relevance. Sleep Med Clin. 2010;5:559-570. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2010.08.002

71. Wilson S, Argyropoulos S. Antidepressants and sleep: a qualitative review of the literature. Drugs. 2005;65:927-947. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565070-00003

72. Winokur A, Gary KA, Rodner S, et al. Depression, sleep physiology, and antidepressant drugs. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14:19-28. doi: 10.1002/da.1043

73. Ozdemir PG, Karadag AS, Selvi Y, et al. Assessment of the effects of antihistamine drugs on mood, sleep quality, sleepiness, and dream anxiety. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18:161-168. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2014.907919

74. Okun ML, Ebert R, Saini B. A review of sleep-promoting medications used in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:428-441. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.1106

Insomnia disorder is common throughout the lifespan, affecting up to 22% of the population.1 Insomnia has a negative effect on patients’ quality of life and is associated with reported worse health-related quality of life, greater overall work impairment, and higher utilization of health care resources compared to patients without insomnia.2

Fortunately, many validated diagnostic tools are available to support physicians in the care of affected patients. In addition, many pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options exist. This review endeavors to help you refine the care you provide to patients across the lifespan by reviewing the evidence-based strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in children, adolescents, and adults.

Defining insomnia

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) defines insomnia disorder as a predominant complaint of dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, associated with 1 or more of the following3:

1. Difficulty initiating sleep. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty initiating sleep without caregiver intervention.)

2. Difficulty maintaining sleep, characterized by frequent awakenings or problems returning to sleep after awakenings. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty returning to sleep without caregiver intervention.)

3. Early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep.

Sleep difficulty must be present for at least 3 months and must occur at least 3 nights per week to be classified as persistent insomnia.3 If symptoms last fewer than 3 months, insomnia is considered acute, which has a different DSM-5 code ("other specified insomnia disorder").3 Primary insomnia is its own diagnosis that cannot be defined by other sleep-wake cycle disorders, mental health conditions, or medical diagnoses that cause sleep disturbances, nor is it attributable to the physiologic effects of a substance (eg, substance use disorders, medication effects).3

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3) notably consolidates all insomnia diagnoses (ie, “primary” and “comorbid”) under a single diagnosis (“chronic insomnia disorder”), which is a distinction from the DSM-5 diagnosis in terms of classification.4 Diagnosis of insomnia requires the presence of 3 criteria: (1) persistence of sleep difficulty, (2) adequate opportunity for sleep, and (3) associated daytime dysfunction.5

How insomnia affects specific patient populations

Children and adolescents. Appropriate screening, diagnosis, and interventions for insomnia in children and adolescents are associated with better health outcomes, including improved attention, behavior, learning, memory, emotional regulation, quality of life, and mental and physical health.6 In one study of insomnia in the pediatric population (N = 1038), 41% of parents reported symptoms of sleep disturbances in their children.7 Pediatric insomnia can lead to impaired attention, poor academic performance, and behavioral disturbances.7 In addition, there is a high prevalence of sleep disturbances in children with neurodevelopmental disorders.8

Insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder in adolescents but frequently goes unrecognized, and therefore is underdiagnosed and undertreated.9 Insomnia in adolescents is associated with depression and suicidality.9-12 Growing evidence also links it to anorexia nervosa,13 substance use disorders,14 and impaired neurocognitive function.15

Continue to: Pregnant women

Pregnant women. Sleep disorders in pregnancy are common and influenced by multiple factors. A meta-analysis found that 57% to 74% of women in various trimesters of pregnancy reported subthreshold symptoms of insomnia16; however, changes in sleep duration and sleep quality during pregnancy may be related to hormonal, physiologic, metabolic, psychological, and posture mechanisms.17,18

Sleep quality also worsens as pregnancy progresses.16 Insomnia coupled with poor sleep quality has been shown to increase the risk for postpartum depression, premature delivery, prolonged labor, and cesarean delivery, as well as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, stillbirth, and large-for-gestational-age infants.19,20

Older adults. Insomnia is a common complaint in the geriatric population and is associated with significant morbidity, as well as higher rates of depression and suicidality.21 Circadian rhythms change and sleep cycles advance as people age, leading to a decrease in total sleep time, earlier sleep onset, earlier awakenings,and increased frequency of waking after sleep onset.21,22 Advanced age, polypharmacy, and high medical comorbidity increase insomnia prevalence.23

Studies have shown that older adults who sleep fewer than 5 hours per night have an increased risk for diabetes and metabolic syndrome.21 Sleep loss also has been linked to increased rates of hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and possibly stroke.21,22 Poor sleep has been associated with increased rates of cortical atrophy in community-dwelling older adults.21 Daytime drowsiness increases fall risk.22 Older adults with self-reported decreased physical function also had increased rates of insomnia and increased rates of daytime sleepiness.22

Making the diagnosis: What to ask, tools to use

Clinical evaluation is most helpful for diagnosing insomnia.24 A complete work-up includes physical examination, review of medications and supplements, evaluation of a 2-week sleep diary (kept by the patient, parent, or caregiver), and assessment using a validated sleep-quality rating scale.24 Be sure to obtain a complete health history, including medical events, substance use, and psychiatric history.24

Continue to: Inquire about sleep initiation...

Inquire about sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, and early awakening, as well as behavioral and environmental factors that may contribute to sleep concerns.10,18 Consider medical sleep disorders that have overlapping symptoms with insomnia, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), restless leg syndrome (RLS), or circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders. If there are co-occurring chronic medical problems, reassess insomnia symptoms after the other medical diagnoses are controlled.

TABLE 125-29 includes a list of validated screening tools for insomnia and where they can be accessed. Recommended screening tools for children and adolescents include daytime sleepiness questionnaires, comprehensive sleep instruments, and self-assessments.25,30 Although several studies of insomnia in pregnancy have used tools listed in TABLE 1,25-29 only the Insomnia Severity Index has been validated for use with this population.26,27 Diagnosis of insomnia in older adults requires a comprehensive sleep history collected from the patient, partners, or caregivers.21

Measuring sleep performance

Several aspects of insomnia (defined in TABLE 231-33) are targeted as outcome measures when treating patients. Sleep-onset latency, total sleep time, and wake-after-sleep onset are all formally measured by polysomnography.31-33 Use polysomnography when you suspect OSA, narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, periodic limb movement disorder, RLS, REM behavior disorder (characterized by the loss of normal muscle atonia and dream enactment behavior that is violent in nature34), or parasomnias. Home polysomnography testing is appropriate for adult patients who meet criteria for OSA and have uncomplicated insomnia.35 Self-reporting (use of sleep logs) and actigraphy (measurement by wearable monitoring devices) may be more accessible methods for gathering sleep data from patients. Use of wearable consumer sleep technology such as heart rate monitors with corresponding smartphone applications (eg, Fitbit, Jawbone Up devices, and the Whoop device) are increasing as a means of monitoring sleep as well as delivering insomnia interventions.36

Actigraphy has been shown to produce significantly distinct results from self-reporting when measuring total sleep time, sleep-onset latency, wake-after-sleep onset, and sleep efficiency in adult and pediatric patients with insomnia.37 Actigraphy yields distinct estimates of sleep patterns when compared to sleep logs, which suggests that while both measures are often correlated, actigraphy has utility in assessing sleep continuity in conjunction with sleep logs in terms of diagnostic and posttreatment assessment.37

Continue to: Treatment options

Treatment options: Start with the nonpharmacologic

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are available for the treatment of insomnia. Starting with nonpharmacologic options is preferred.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

Sleep hygiene. Poor sleep hygiene can contribute to insomnia but does not cause it.31 Healthy sleep habits include keeping the sleep environment quiet, free of interruptions, and at an adequate temperature; adhering to a regular sleep schedule; avoiding naps; going to bed when drowsy; getting out of bed if not asleep within 15 to 20 minutes and returning when drowsy; exercising regularly; and avoiding caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and other substances that interfere with sleep.24 Technology use prior to bedtime is prevalent and associated with sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances.38

Sleep hygiene education is often insufficient on its own.31 But it has been shown to benefit older adults with insomnia.19,32

Sleep hygiene during pregnancy emphasizes drinking fluids only in the daytime to avoid awakening to urinate at night, avoiding specific foods to decrease heartburn, napping only in the early part of the day, and sleeping on either the left or the right side of the body with knees and hips bent and a pillow under pressure points in the second and third trimesters.18,39

Pediatric insomnia. Sleep hygiene is an important first-line treatment for pediatric insomnia, especially among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.40

Continue to: CBT-I

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). US and European guidelines recommend CBT-I—a multicomponent, nonpharmacologic, insomnia-focused psychotherapy—as a first-line treatment for short- and long-term insomnia32,41,42 across a wide range of patient demographics.17,43-47 CBT-I is a multiweek intensive treatment that combines sleep hygiene practices with cognitive therapy and behavioral interventions, including stimulus control, sleep restriction, and relaxation training.32,48 CBT-I monotherapy has been shown to have greater efficacy than sleep hygiene education for patients with insomnia, especially for those with medical or psychiatric comorbidities.49 It also has been shown to be effective when delivered in person or even digitally.50-52 For example, CBT-I Coach is a mobile application for people who are already engaged in CBT-I with a health care provider; it provides a structured program to alleviate symptoms.53

Although CBT-I methods are appropriate for adolescents and school-aged children, evaluations of the efficacy of the individual components (stimulus control, arousal reduction, cognitive therapy, improved sleep hygiene practices, and sleep restriction) are needed to understand what methods are most effective in this population.9

Cognitive and/or behavioral Interventions. Cognitive therapy (to change negative thoughts about sleep) and behavioral interventions (eg, changes to sleep routines, sleep restriction, moving the child’s bedtime to match the time of falling asleep [bedtime fading],41 stimulus control)9,43,54-56 may be used independently. Separate meta-analyses support the use of cognitive and behavioral interventions for adolescent insomnia,9,43 school-aged children with insomnia and sleep difficulties,43,49 and adolescents with sleep difficulties and daytime fatigue.41 The trials for children and adolescents followed the same recommendations for treatment as CBT-I but often used fewer components of the treatment, resulting in focused cognitive or behavioral interventions.

One controlled evaluation showed support for separate cognitive and behavioral techniques for insomnia in children.54 A meta-analysis (6 studies; N = 529) found that total sleep time, as measured with actigraphy, improved among school-aged children and adolescents with insomnia after treatment with 4 or more types of cognitive or behavioral therapy sessions.43 Sleep-onset latency, measured by actigraphy and sleep diaries, decreased in the intervention group.43

A controlled evaluation of CBT for behavioral insomnia in school-aged children (N = 42) randomized participants to CBT (n = 21) or waitlist control (n = 21).54 The 6 CBT sessions combined behavioral sleep medicine techniques (ie, sleep restriction) with anxiety treatment techniques (eg, cognitive restructuring).54 Those in the intervention group showed statistically significant improvement in sleep latency, wake-after-sleep onset, and sleep efficiency (all P ≤ .003), compared with controls.54 Total sleep time was unaffected by the intervention. A notable change was the number of patients who still had an insomnia diagnosis postintervention. Among children in the CBT group, 14.3% met diagnostic criteria vs 95% of children in the control group.54 Similarly, at the 1-month follow-up, 9.5% of CBT group members still had insomnia, compared with 86.7% of the control group participants.54

Continue to: Multiple randomized and nonranomized studies...

Multiple randomized and nonrandomized studies have found that infants also respond to behavioral interventions, such as establishing regular daytime and sleep routines, reducing environmental noises or distractions, and allowing for self-soothing at bedtime.55 A controlled trial (N = 279) of newborns and their mothers evaluated sleep interventions that included guidance on bedtime sleep routines, starting the routine 30 to 45 minutes before bedtime, choosing age-appropriate calming bedtime activities, not using feeding as the last step before bedtime, and offering the child choices with their routine.56 The intervention group demonstrated longer sleep duration (624.6 ± 67.6 minutes vs 602.9 ± 76.1 minutes; P = .01) at 40 weeks postintervention compared with the control group.56

The clinically significant outcomes of this study are related to the guidance offered to parents to help infants achieve longer sleep. More intervention-group infants were allowed to self-soothe to sleep without being held or fed, had earlier bedtimes, and fell asleep ≤ 15 minutes after being put into bed than their counterparts in the control group.56

Exercise. As a sole intervention, exercise for insomnia is readily available and low cost, but it is not universally effective. One study of patients older than 60 years (N = 43) showed that a 16-week moderate exercise regimen slightly improved total sleep time by an average of 42 minutes (P = .05), sleep-onset latency improved an average of 11.5 minutes (P = .007), and global sleep quality improved by 3.4 points as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; P ≤ .01).57 No significant improvements occurred in sleep efficiency. Exercise is one of several nonpharmacologic alternatives for treating insomnia in pregnancy.58

A lack of uniformity in patient populations, intervention protocols, and outcome measures confounded results of 2 systematic reviews that included comparisons of yoga or tai chi as standalone alternatives to CBT-I for insomnia treatment.58,59 Other interventions, such as mindfulness or relaxation training, have been studied as insomnia interventions, but no conclusive evidence about their efficacy exists.45,59

Pharmacologic interventions

Pharmacologic treatment should not be the sole intervention for the treatment of insomnia but should be used in combination with nonpharmacologic interventions.32 Of note, only low-quality evidence exists for any pharmacologic interventions for insomnia.32 The decision to prescribe medications should rely on the predominant sleep complaint, with sleep maintenance and sleep-onset latency as the guiding factors.32 Medications used for insomnia treatment (TABLE 332,60,61)are classified according to these and other sleep outcomes described in TABLE 1.25-29 Prescribe them at the lowest dose and for the shortest amount of time possible.32,62 Avoid medications listed in TABLE 432,36,59,60,62-69 because data showing clinically significant improvements in insomnia are lacking, and analysis for potential harms is inadequate.32

Continue to: Melatonin is not recommended

Melatonin is not recommended for treating insomnia in adults, pregnant patients, older adults, or most children because its effects are clinically insignificant,32 residual sedation has been reported,60 and no analysis of harms has been undertaken.32 Despite this, melatonin is frequently utilized for insomnia, and patients take over-the-counter melatonin for a myriad of sleep complaints. Melatonin is indicated in the treatment of insomnia in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. (See discussion in "Prescribing for children.")

Hypnotics are medications licensed for short-term sleep promotion in adults and can induce tolerance and dependence.32 Nonbenzodiazepine-receptor agonists at clinical doses do not appear to suppress REM sleep, although there are reports of increases in latency to REM sleep.70

Antidepressants. Although treatment of insomnia with antidepressants is widespread, evidence of their efficacy is unclear.32,62 The tolerability and safety of antidepressants for insomnia also are uncertain due to limited reporting of adverse events.32

The use of sedating antidepressants may be driven by concern over the longer-term use of hypnotics and the limited availability of psychological treatments including CBT-I.32 Sedating antidepressants are indicated for comorbid or secondary insomnia (attributable to mental health conditions, medical conditions, other sleep disorders, or substance use or misuse); however, there are few clinical trials studying them for primary insomnia treatment.62 Antidepressants—tricyclic antidepressants included—can reduce the amount of REM sleep and increase REM sleep-onset latency.71,72

Antihistamines and antipsychotics. Although antihistamines (eg, hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine) and antipsychotics frequently are prescribed off-label for primary insomnia, there is a lack of evidence to support either type of medication for this purpose.36,62,73 H1-antihistamines such as hydroxyzine increase REM-onset latency and reduce the duration of REM sleep.73 Depending on the specific medication, second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine and quetiapine have mixed effects on REM sleep parameters.65

Continue to: Prescribing for children

Prescribing for children. There is no FDA-approved medication for the treatment of insomnia in children.52 However, melatonin has shown promising results for treating insomnia in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. A systematic review (13 trials; N = 682) with meta-analysis (9 studies; n = 541) showed that melatonin significantly improved total sleep time compared with placebo (mean difference [MD] = 48.26 minutes; 95% CI, 36.78-59.73).8 In 11 studies (n = 581), sleep-onset latency improved significantly with melatonin use.8 No difference was noted in the frequency of wake-after-sleep onset.8 No medication-related adverse events were reported. Heterogeneity (I2 = 31%) and inconsistency among included studies shed doubt on the findings; therefore, further research is needed.8

Prescribing in pregnancy. Prescribing medications to treat insomnia in pregnancy is complex and controversial. No consistency exists among guidelines and recommendations for treating insomnia in the pregnant population. Pharmacotherapy for insomnia is frequently prescribed off-label in pregnant patients. Examples include benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, antidepressants, and gamma-aminobutyric acid–reuptake inhibitors.45

Pharmacotherapy in pregnancy is a unique challenge, wherein clinicians consider not only the potential drug toxicity to the fetus but also the potential changes in the pregnant patient’s pharmacokinetics that influence appropriate medication doses.39,74 Worth noting: Zolpidem has been associated with preterm birth, cesarean birth, and low-birth-weight infants.45,74 The lack of clinical trials of pharmacotherapy in pregnant patients results in a limited understanding of medication effects on long-term health and safety outcomes in this population.39,74

A review of 3 studies with small sample sizes found that when antidepressants or antihistamines were taken during pregnancy, neither had significant adverse effects on mother or child.68 Weigh the risks of medications with the risk for disease burden and apply a shared decision-making approach with the patient, including providing an accurate assessment of risks and safety information regarding medication use.39 Online resources such as ReproTox (www.reprotox.org) and MotherToBaby (https://mothertobaby.org) are available to support clinicians treating pregnant and lactating patients.39

Prescribing for older adults. Treatment of insomnia in older adults requires a multifactorial approach.22 For all older adults, start interventions with nonpharmacologic treatments for insomnia followed by treatment of any underlying medical and psychiatric disorders that affect sleep.21 If medications are required, start with the lowest dose and titrate upward slowly. Use sedating low-dose antidepressants for insomnia only when the older patient has comorbid depression.60 Although nonbenzodiazepine-receptor agonists have improved safety profiles compared with benzodiazepines, their use for older adults should be limited because of adverse effects that include dementia, serious injury, and falls with fractures.60

Keep these points in mind

Poor sleep has many detrimental health effects and can significantly affect quality of life for patients across the lifespan. Use nonpharmacologic interventions—such as sleep hygiene education, CBT-I, and cognitive/behavioral therapies—as first-line treatments. When utilizing pharmacotherapy for insomnia, consider the patient’s distressing symptoms of insomnia as guideposts for prescribing. Use pharmacologic treatments intermittently, short term, and in conjunction with nonpharmacologic options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Angela L. Colistra, PhD, LPC, CAADC, CCS, 707 Hamilton Street, 8th floor, LVHN Department of Family Medicine, Allentown, PA 18101; angela.colistra@lvhn.org

Insomnia disorder is common throughout the lifespan, affecting up to 22% of the population.1 Insomnia has a negative effect on patients’ quality of life and is associated with reported worse health-related quality of life, greater overall work impairment, and higher utilization of health care resources compared to patients without insomnia.2

Fortunately, many validated diagnostic tools are available to support physicians in the care of affected patients. In addition, many pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options exist. This review endeavors to help you refine the care you provide to patients across the lifespan by reviewing the evidence-based strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in children, adolescents, and adults.

Defining insomnia

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) defines insomnia disorder as a predominant complaint of dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, associated with 1 or more of the following3:

1. Difficulty initiating sleep. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty initiating sleep without caregiver intervention.)

2. Difficulty maintaining sleep, characterized by frequent awakenings or problems returning to sleep after awakenings. (In children, this may manifest as difficulty returning to sleep without caregiver intervention.)

3. Early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep.

Sleep difficulty must be present for at least 3 months and must occur at least 3 nights per week to be classified as persistent insomnia.3 If symptoms last fewer than 3 months, insomnia is considered acute, which has a different DSM-5 code ("other specified insomnia disorder").3 Primary insomnia is its own diagnosis that cannot be defined by other sleep-wake cycle disorders, mental health conditions, or medical diagnoses that cause sleep disturbances, nor is it attributable to the physiologic effects of a substance (eg, substance use disorders, medication effects).3

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3) notably consolidates all insomnia diagnoses (ie, “primary” and “comorbid”) under a single diagnosis (“chronic insomnia disorder”), which is a distinction from the DSM-5 diagnosis in terms of classification.4 Diagnosis of insomnia requires the presence of 3 criteria: (1) persistence of sleep difficulty, (2) adequate opportunity for sleep, and (3) associated daytime dysfunction.5

How insomnia affects specific patient populations

Children and adolescents. Appropriate screening, diagnosis, and interventions for insomnia in children and adolescents are associated with better health outcomes, including improved attention, behavior, learning, memory, emotional regulation, quality of life, and mental and physical health.6 In one study of insomnia in the pediatric population (N = 1038), 41% of parents reported symptoms of sleep disturbances in their children.7 Pediatric insomnia can lead to impaired attention, poor academic performance, and behavioral disturbances.7 In addition, there is a high prevalence of sleep disturbances in children with neurodevelopmental disorders.8

Insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder in adolescents but frequently goes unrecognized, and therefore is underdiagnosed and undertreated.9 Insomnia in adolescents is associated with depression and suicidality.9-12 Growing evidence also links it to anorexia nervosa,13 substance use disorders,14 and impaired neurocognitive function.15

Continue to: Pregnant women

Pregnant women. Sleep disorders in pregnancy are common and influenced by multiple factors. A meta-analysis found that 57% to 74% of women in various trimesters of pregnancy reported subthreshold symptoms of insomnia16; however, changes in sleep duration and sleep quality during pregnancy may be related to hormonal, physiologic, metabolic, psychological, and posture mechanisms.17,18

Sleep quality also worsens as pregnancy progresses.16 Insomnia coupled with poor sleep quality has been shown to increase the risk for postpartum depression, premature delivery, prolonged labor, and cesarean delivery, as well as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, stillbirth, and large-for-gestational-age infants.19,20

Older adults. Insomnia is a common complaint in the geriatric population and is associated with significant morbidity, as well as higher rates of depression and suicidality.21 Circadian rhythms change and sleep cycles advance as people age, leading to a decrease in total sleep time, earlier sleep onset, earlier awakenings,and increased frequency of waking after sleep onset.21,22 Advanced age, polypharmacy, and high medical comorbidity increase insomnia prevalence.23

Studies have shown that older adults who sleep fewer than 5 hours per night have an increased risk for diabetes and metabolic syndrome.21 Sleep loss also has been linked to increased rates of hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and possibly stroke.21,22 Poor sleep has been associated with increased rates of cortical atrophy in community-dwelling older adults.21 Daytime drowsiness increases fall risk.22 Older adults with self-reported decreased physical function also had increased rates of insomnia and increased rates of daytime sleepiness.22

Making the diagnosis: What to ask, tools to use

Clinical evaluation is most helpful for diagnosing insomnia.24 A complete work-up includes physical examination, review of medications and supplements, evaluation of a 2-week sleep diary (kept by the patient, parent, or caregiver), and assessment using a validated sleep-quality rating scale.24 Be sure to obtain a complete health history, including medical events, substance use, and psychiatric history.24

Continue to: Inquire about sleep initiation...

Inquire about sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, and early awakening, as well as behavioral and environmental factors that may contribute to sleep concerns.10,18 Consider medical sleep disorders that have overlapping symptoms with insomnia, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), restless leg syndrome (RLS), or circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders. If there are co-occurring chronic medical problems, reassess insomnia symptoms after the other medical diagnoses are controlled.

TABLE 125-29 includes a list of validated screening tools for insomnia and where they can be accessed. Recommended screening tools for children and adolescents include daytime sleepiness questionnaires, comprehensive sleep instruments, and self-assessments.25,30 Although several studies of insomnia in pregnancy have used tools listed in TABLE 1,25-29 only the Insomnia Severity Index has been validated for use with this population.26,27 Diagnosis of insomnia in older adults requires a comprehensive sleep history collected from the patient, partners, or caregivers.21

Measuring sleep performance

Several aspects of insomnia (defined in TABLE 231-33) are targeted as outcome measures when treating patients. Sleep-onset latency, total sleep time, and wake-after-sleep onset are all formally measured by polysomnography.31-33 Use polysomnography when you suspect OSA, narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, periodic limb movement disorder, RLS, REM behavior disorder (characterized by the loss of normal muscle atonia and dream enactment behavior that is violent in nature34), or parasomnias. Home polysomnography testing is appropriate for adult patients who meet criteria for OSA and have uncomplicated insomnia.35 Self-reporting (use of sleep logs) and actigraphy (measurement by wearable monitoring devices) may be more accessible methods for gathering sleep data from patients. Use of wearable consumer sleep technology such as heart rate monitors with corresponding smartphone applications (eg, Fitbit, Jawbone Up devices, and the Whoop device) are increasing as a means of monitoring sleep as well as delivering insomnia interventions.36

Actigraphy has been shown to produce significantly distinct results from self-reporting when measuring total sleep time, sleep-onset latency, wake-after-sleep onset, and sleep efficiency in adult and pediatric patients with insomnia.37 Actigraphy yields distinct estimates of sleep patterns when compared to sleep logs, which suggests that while both measures are often correlated, actigraphy has utility in assessing sleep continuity in conjunction with sleep logs in terms of diagnostic and posttreatment assessment.37

Continue to: Treatment options

Treatment options: Start with the nonpharmacologic

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are available for the treatment of insomnia. Starting with nonpharmacologic options is preferred.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

Sleep hygiene. Poor sleep hygiene can contribute to insomnia but does not cause it.31 Healthy sleep habits include keeping the sleep environment quiet, free of interruptions, and at an adequate temperature; adhering to a regular sleep schedule; avoiding naps; going to bed when drowsy; getting out of bed if not asleep within 15 to 20 minutes and returning when drowsy; exercising regularly; and avoiding caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and other substances that interfere with sleep.24 Technology use prior to bedtime is prevalent and associated with sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances.38

Sleep hygiene education is often insufficient on its own.31 But it has been shown to benefit older adults with insomnia.19,32

Sleep hygiene during pregnancy emphasizes drinking fluids only in the daytime to avoid awakening to urinate at night, avoiding specific foods to decrease heartburn, napping only in the early part of the day, and sleeping on either the left or the right side of the body with knees and hips bent and a pillow under pressure points in the second and third trimesters.18,39

Pediatric insomnia. Sleep hygiene is an important first-line treatment for pediatric insomnia, especially among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.40

Continue to: CBT-I

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). US and European guidelines recommend CBT-I—a multicomponent, nonpharmacologic, insomnia-focused psychotherapy—as a first-line treatment for short- and long-term insomnia32,41,42 across a wide range of patient demographics.17,43-47 CBT-I is a multiweek intensive treatment that combines sleep hygiene practices with cognitive therapy and behavioral interventions, including stimulus control, sleep restriction, and relaxation training.32,48 CBT-I monotherapy has been shown to have greater efficacy than sleep hygiene education for patients with insomnia, especially for those with medical or psychiatric comorbidities.49 It also has been shown to be effective when delivered in person or even digitally.50-52 For example, CBT-I Coach is a mobile application for people who are already engaged in CBT-I with a health care provider; it provides a structured program to alleviate symptoms.53

Although CBT-I methods are appropriate for adolescents and school-aged children, evaluations of the efficacy of the individual components (stimulus control, arousal reduction, cognitive therapy, improved sleep hygiene practices, and sleep restriction) are needed to understand what methods are most effective in this population.9

Cognitive and/or behavioral Interventions. Cognitive therapy (to change negative thoughts about sleep) and behavioral interventions (eg, changes to sleep routines, sleep restriction, moving the child’s bedtime to match the time of falling asleep [bedtime fading],41 stimulus control)9,43,54-56 may be used independently. Separate meta-analyses support the use of cognitive and behavioral interventions for adolescent insomnia,9,43 school-aged children with insomnia and sleep difficulties,43,49 and adolescents with sleep difficulties and daytime fatigue.41 The trials for children and adolescents followed the same recommendations for treatment as CBT-I but often used fewer components of the treatment, resulting in focused cognitive or behavioral interventions.

One controlled evaluation showed support for separate cognitive and behavioral techniques for insomnia in children.54 A meta-analysis (6 studies; N = 529) found that total sleep time, as measured with actigraphy, improved among school-aged children and adolescents with insomnia after treatment with 4 or more types of cognitive or behavioral therapy sessions.43 Sleep-onset latency, measured by actigraphy and sleep diaries, decreased in the intervention group.43

A controlled evaluation of CBT for behavioral insomnia in school-aged children (N = 42) randomized participants to CBT (n = 21) or waitlist control (n = 21).54 The 6 CBT sessions combined behavioral sleep medicine techniques (ie, sleep restriction) with anxiety treatment techniques (eg, cognitive restructuring).54 Those in the intervention group showed statistically significant improvement in sleep latency, wake-after-sleep onset, and sleep efficiency (all P ≤ .003), compared with controls.54 Total sleep time was unaffected by the intervention. A notable change was the number of patients who still had an insomnia diagnosis postintervention. Among children in the CBT group, 14.3% met diagnostic criteria vs 95% of children in the control group.54 Similarly, at the 1-month follow-up, 9.5% of CBT group members still had insomnia, compared with 86.7% of the control group participants.54

Continue to: Multiple randomized and nonranomized studies...

Multiple randomized and nonrandomized studies have found that infants also respond to behavioral interventions, such as establishing regular daytime and sleep routines, reducing environmental noises or distractions, and allowing for self-soothing at bedtime.55 A controlled trial (N = 279) of newborns and their mothers evaluated sleep interventions that included guidance on bedtime sleep routines, starting the routine 30 to 45 minutes before bedtime, choosing age-appropriate calming bedtime activities, not using feeding as the last step before bedtime, and offering the child choices with their routine.56 The intervention group demonstrated longer sleep duration (624.6 ± 67.6 minutes vs 602.9 ± 76.1 minutes; P = .01) at 40 weeks postintervention compared with the control group.56

The clinically significant outcomes of this study are related to the guidance offered to parents to help infants achieve longer sleep. More intervention-group infants were allowed to self-soothe to sleep without being held or fed, had earlier bedtimes, and fell asleep ≤ 15 minutes after being put into bed than their counterparts in the control group.56

Exercise. As a sole intervention, exercise for insomnia is readily available and low cost, but it is not universally effective. One study of patients older than 60 years (N = 43) showed that a 16-week moderate exercise regimen slightly improved total sleep time by an average of 42 minutes (P = .05), sleep-onset latency improved an average of 11.5 minutes (P = .007), and global sleep quality improved by 3.4 points as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; P ≤ .01).57 No significant improvements occurred in sleep efficiency. Exercise is one of several nonpharmacologic alternatives for treating insomnia in pregnancy.58

A lack of uniformity in patient populations, intervention protocols, and outcome measures confounded results of 2 systematic reviews that included comparisons of yoga or tai chi as standalone alternatives to CBT-I for insomnia treatment.58,59 Other interventions, such as mindfulness or relaxation training, have been studied as insomnia interventions, but no conclusive evidence about their efficacy exists.45,59

Pharmacologic interventions

Pharmacologic treatment should not be the sole intervention for the treatment of insomnia but should be used in combination with nonpharmacologic interventions.32 Of note, only low-quality evidence exists for any pharmacologic interventions for insomnia.32 The decision to prescribe medications should rely on the predominant sleep complaint, with sleep maintenance and sleep-onset latency as the guiding factors.32 Medications used for insomnia treatment (TABLE 332,60,61)are classified according to these and other sleep outcomes described in TABLE 1.25-29 Prescribe them at the lowest dose and for the shortest amount of time possible.32,62 Avoid medications listed in TABLE 432,36,59,60,62-69 because data showing clinically significant improvements in insomnia are lacking, and analysis for potential harms is inadequate.32

Continue to: Melatonin is not recommended

Melatonin is not recommended for treating insomnia in adults, pregnant patients, older adults, or most children because its effects are clinically insignificant,32 residual sedation has been reported,60 and no analysis of harms has been undertaken.32 Despite this, melatonin is frequently utilized for insomnia, and patients take over-the-counter melatonin for a myriad of sleep complaints. Melatonin is indicated in the treatment of insomnia in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. (See discussion in "Prescribing for children.")

Hypnotics are medications licensed for short-term sleep promotion in adults and can induce tolerance and dependence.32 Nonbenzodiazepine-receptor agonists at clinical doses do not appear to suppress REM sleep, although there are reports of increases in latency to REM sleep.70

Antidepressants. Although treatment of insomnia with antidepressants is widespread, evidence of their efficacy is unclear.32,62 The tolerability and safety of antidepressants for insomnia also are uncertain due to limited reporting of adverse events.32

The use of sedating antidepressants may be driven by concern over the longer-term use of hypnotics and the limited availability of psychological treatments including CBT-I.32 Sedating antidepressants are indicated for comorbid or secondary insomnia (attributable to mental health conditions, medical conditions, other sleep disorders, or substance use or misuse); however, there are few clinical trials studying them for primary insomnia treatment.62 Antidepressants—tricyclic antidepressants included—can reduce the amount of REM sleep and increase REM sleep-onset latency.71,72

Antihistamines and antipsychotics. Although antihistamines (eg, hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine) and antipsychotics frequently are prescribed off-label for primary insomnia, there is a lack of evidence to support either type of medication for this purpose.36,62,73 H1-antihistamines such as hydroxyzine increase REM-onset latency and reduce the duration of REM sleep.73 Depending on the specific medication, second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine and quetiapine have mixed effects on REM sleep parameters.65

Continue to: Prescribing for children