User login

The jury is still out on the costs and efficacy of biological mesh implants for abdominal wall hernia repair, according to a systematic review of the literature.

Of 20 articles that met search criteria, only 3 were comparative studies and none was a randomized clinical trial. In fact, most were case series involving convenience samples of patients at single institutions, Dr. Sergio Huerta of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his colleagues reported online Jan. 27 in JAMA Surgery.

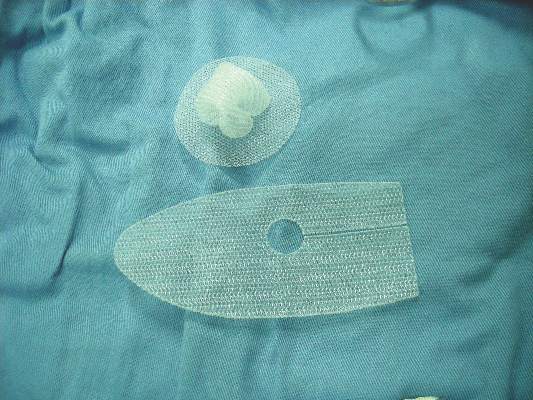

The authors used multiple electronic databases to identify articles published between 1948 and June 30, 2015, on the use of biological mesh materials for reinforcement of the abdominal wall for hernia repair. Included were 14 articles that described outcomes with human acellular dermal matrix, 2 that reported results for porcine collagen intestinal submucosa derivatives, 3 that reported on porcine acelluar collagen skin derivatives, and 1 that described results for bovine pericardium.

Several problems were noted with respect to the studies, including widely varying follow-up time, operative technique, types of mesh used, and patient selection criteria. Also, outcome measures were not reported consistently across studies.

In addition, 16 of the 20 studies that met search criteria did not report investigator conflicts of interest, the authors reported (JAMA Surg. 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.10001/jamasurg.2015.5234).

Notably, all the meshes used in the studies were approved by the Food and Drug Administration and were considered to be comparable to a group of nonbiological predicate devices, which cost up to 25% less than the biological equivalents, they noted.

“We were unable to find any evidence that supported the use of expensive biological material relative to low-cost synthetic mesh. In fact, with one exception, the biological materials became commercially available by showing that these materials were equivalent to low-cost established synthetic mesh material in an FDA 510(k) approval process. This process does not require phase 0 through IV clinical trials as required for drugs or biological agents,” they wrote, noting that the one material that bypassed the 510(k) process (Alloderm) was not required to demonstrate equivalence because it was classified as human transplanted tissue.

Biological mesh materials were introduced in the 1990s to minimize the risk of complications commonly seen with the use of synthetic mesh for abdominal wall hernia repair – one of the most common procedures performed by general surgeons, the authors explained.

“Because the outcomes for biological mesh material are perceived to be better than those for polymer-based prosthetic mesh replacement materials, the use of biological grafts increased exponentially without clear clinical evidence of efficacy,” they wrote.

The current review suggests that the evidence remains insufficient to determine whether cost and clinical benefits exist.

“It is generally assumed that FDA-approved drug or biological agents have been rigorously evaluated and that there is demonstrable safety and efficacy. This is not the case for 510(k) medical devices. Before using a new medical device, physicians should know the approval basis for the device and recognize that if it is a 510(k) device neither safety nor efficacy is ensured,” they said, adding that physicians should assume such devices are no better than predicate devices to which they are equivalent, and that “there can be no justification for purchasing a more expensive device when a lower-cost predicate device, which is equivalent, is available.”

Though limited by certain factors such as lack of access to detailed FDA information such as the specific criteria used to determine equivalence, and a lack of published literature on the full market penetration of biological mesh materials vs. nonbiological counterparts, the authors maintained that until evidence demonstrates superiority of biological materials, the expense associated with their use cannot be justified.

This study was supported by the Hudson-Penn Endowment fund at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Balancing the need for innovation against the practicalities of demonstrating clinical benefit for novel ideas is a fundamental problem in surgery – a problem highlighted by Heurta et al., Dr. Benjamin K. Poulose and his colleagues said in an editorial.

“This issue is particularly timely given an unsustainable trajectory of health care spending in the United States,” they wrote (JAMA Surg 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg2015.5236).

Like the authors of the literature review, the editorial authors stressed the importance of understanding the limitations of the 510(k) process, and noted that surgeons should consider that the FDA sees them as “the group responsible for understanding and evaluating the data before using expensive medical devices.

“Understanding who is in charge of making sure that the devices that we use during surgery are safe and effective is critical. Likely, it will require a collaborative effort of the FDA, medical device companies, and physicians,” they wrote. Establishing a more formal system of postmarketing surveillance for higher-risk medical devices will benefit patients, they added. Current efforts suffer from reliance on self-reporting and lack of standardized data collection.

Postmarketing surveillance can be greatly improved by directly linking medical device approval with the support of high-quality registries, and the end result should provide transparent data for monitoring effectiveness and safety to drive value-based care and maintain innovation, they said.

Dr. Poulose is with Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. Dr. Poulose reported receiving personal fees from Ariste Medical for consulting work, and research grants from Bard-Davol outside the submitted work.

Balancing the need for innovation against the practicalities of demonstrating clinical benefit for novel ideas is a fundamental problem in surgery – a problem highlighted by Heurta et al., Dr. Benjamin K. Poulose and his colleagues said in an editorial.

“This issue is particularly timely given an unsustainable trajectory of health care spending in the United States,” they wrote (JAMA Surg 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg2015.5236).

Like the authors of the literature review, the editorial authors stressed the importance of understanding the limitations of the 510(k) process, and noted that surgeons should consider that the FDA sees them as “the group responsible for understanding and evaluating the data before using expensive medical devices.

“Understanding who is in charge of making sure that the devices that we use during surgery are safe and effective is critical. Likely, it will require a collaborative effort of the FDA, medical device companies, and physicians,” they wrote. Establishing a more formal system of postmarketing surveillance for higher-risk medical devices will benefit patients, they added. Current efforts suffer from reliance on self-reporting and lack of standardized data collection.

Postmarketing surveillance can be greatly improved by directly linking medical device approval with the support of high-quality registries, and the end result should provide transparent data for monitoring effectiveness and safety to drive value-based care and maintain innovation, they said.

Dr. Poulose is with Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. Dr. Poulose reported receiving personal fees from Ariste Medical for consulting work, and research grants from Bard-Davol outside the submitted work.

Balancing the need for innovation against the practicalities of demonstrating clinical benefit for novel ideas is a fundamental problem in surgery – a problem highlighted by Heurta et al., Dr. Benjamin K. Poulose and his colleagues said in an editorial.

“This issue is particularly timely given an unsustainable trajectory of health care spending in the United States,” they wrote (JAMA Surg 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg2015.5236).

Like the authors of the literature review, the editorial authors stressed the importance of understanding the limitations of the 510(k) process, and noted that surgeons should consider that the FDA sees them as “the group responsible for understanding and evaluating the data before using expensive medical devices.

“Understanding who is in charge of making sure that the devices that we use during surgery are safe and effective is critical. Likely, it will require a collaborative effort of the FDA, medical device companies, and physicians,” they wrote. Establishing a more formal system of postmarketing surveillance for higher-risk medical devices will benefit patients, they added. Current efforts suffer from reliance on self-reporting and lack of standardized data collection.

Postmarketing surveillance can be greatly improved by directly linking medical device approval with the support of high-quality registries, and the end result should provide transparent data for monitoring effectiveness and safety to drive value-based care and maintain innovation, they said.

Dr. Poulose is with Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. Dr. Poulose reported receiving personal fees from Ariste Medical for consulting work, and research grants from Bard-Davol outside the submitted work.

The jury is still out on the costs and efficacy of biological mesh implants for abdominal wall hernia repair, according to a systematic review of the literature.

Of 20 articles that met search criteria, only 3 were comparative studies and none was a randomized clinical trial. In fact, most were case series involving convenience samples of patients at single institutions, Dr. Sergio Huerta of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his colleagues reported online Jan. 27 in JAMA Surgery.

The authors used multiple electronic databases to identify articles published between 1948 and June 30, 2015, on the use of biological mesh materials for reinforcement of the abdominal wall for hernia repair. Included were 14 articles that described outcomes with human acellular dermal matrix, 2 that reported results for porcine collagen intestinal submucosa derivatives, 3 that reported on porcine acelluar collagen skin derivatives, and 1 that described results for bovine pericardium.

Several problems were noted with respect to the studies, including widely varying follow-up time, operative technique, types of mesh used, and patient selection criteria. Also, outcome measures were not reported consistently across studies.

In addition, 16 of the 20 studies that met search criteria did not report investigator conflicts of interest, the authors reported (JAMA Surg. 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.10001/jamasurg.2015.5234).

Notably, all the meshes used in the studies were approved by the Food and Drug Administration and were considered to be comparable to a group of nonbiological predicate devices, which cost up to 25% less than the biological equivalents, they noted.

“We were unable to find any evidence that supported the use of expensive biological material relative to low-cost synthetic mesh. In fact, with one exception, the biological materials became commercially available by showing that these materials were equivalent to low-cost established synthetic mesh material in an FDA 510(k) approval process. This process does not require phase 0 through IV clinical trials as required for drugs or biological agents,” they wrote, noting that the one material that bypassed the 510(k) process (Alloderm) was not required to demonstrate equivalence because it was classified as human transplanted tissue.

Biological mesh materials were introduced in the 1990s to minimize the risk of complications commonly seen with the use of synthetic mesh for abdominal wall hernia repair – one of the most common procedures performed by general surgeons, the authors explained.

“Because the outcomes for biological mesh material are perceived to be better than those for polymer-based prosthetic mesh replacement materials, the use of biological grafts increased exponentially without clear clinical evidence of efficacy,” they wrote.

The current review suggests that the evidence remains insufficient to determine whether cost and clinical benefits exist.

“It is generally assumed that FDA-approved drug or biological agents have been rigorously evaluated and that there is demonstrable safety and efficacy. This is not the case for 510(k) medical devices. Before using a new medical device, physicians should know the approval basis for the device and recognize that if it is a 510(k) device neither safety nor efficacy is ensured,” they said, adding that physicians should assume such devices are no better than predicate devices to which they are equivalent, and that “there can be no justification for purchasing a more expensive device when a lower-cost predicate device, which is equivalent, is available.”

Though limited by certain factors such as lack of access to detailed FDA information such as the specific criteria used to determine equivalence, and a lack of published literature on the full market penetration of biological mesh materials vs. nonbiological counterparts, the authors maintained that until evidence demonstrates superiority of biological materials, the expense associated with their use cannot be justified.

This study was supported by the Hudson-Penn Endowment fund at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The jury is still out on the costs and efficacy of biological mesh implants for abdominal wall hernia repair, according to a systematic review of the literature.

Of 20 articles that met search criteria, only 3 were comparative studies and none was a randomized clinical trial. In fact, most were case series involving convenience samples of patients at single institutions, Dr. Sergio Huerta of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his colleagues reported online Jan. 27 in JAMA Surgery.

The authors used multiple electronic databases to identify articles published between 1948 and June 30, 2015, on the use of biological mesh materials for reinforcement of the abdominal wall for hernia repair. Included were 14 articles that described outcomes with human acellular dermal matrix, 2 that reported results for porcine collagen intestinal submucosa derivatives, 3 that reported on porcine acelluar collagen skin derivatives, and 1 that described results for bovine pericardium.

Several problems were noted with respect to the studies, including widely varying follow-up time, operative technique, types of mesh used, and patient selection criteria. Also, outcome measures were not reported consistently across studies.

In addition, 16 of the 20 studies that met search criteria did not report investigator conflicts of interest, the authors reported (JAMA Surg. 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.10001/jamasurg.2015.5234).

Notably, all the meshes used in the studies were approved by the Food and Drug Administration and were considered to be comparable to a group of nonbiological predicate devices, which cost up to 25% less than the biological equivalents, they noted.

“We were unable to find any evidence that supported the use of expensive biological material relative to low-cost synthetic mesh. In fact, with one exception, the biological materials became commercially available by showing that these materials were equivalent to low-cost established synthetic mesh material in an FDA 510(k) approval process. This process does not require phase 0 through IV clinical trials as required for drugs or biological agents,” they wrote, noting that the one material that bypassed the 510(k) process (Alloderm) was not required to demonstrate equivalence because it was classified as human transplanted tissue.

Biological mesh materials were introduced in the 1990s to minimize the risk of complications commonly seen with the use of synthetic mesh for abdominal wall hernia repair – one of the most common procedures performed by general surgeons, the authors explained.

“Because the outcomes for biological mesh material are perceived to be better than those for polymer-based prosthetic mesh replacement materials, the use of biological grafts increased exponentially without clear clinical evidence of efficacy,” they wrote.

The current review suggests that the evidence remains insufficient to determine whether cost and clinical benefits exist.

“It is generally assumed that FDA-approved drug or biological agents have been rigorously evaluated and that there is demonstrable safety and efficacy. This is not the case for 510(k) medical devices. Before using a new medical device, physicians should know the approval basis for the device and recognize that if it is a 510(k) device neither safety nor efficacy is ensured,” they said, adding that physicians should assume such devices are no better than predicate devices to which they are equivalent, and that “there can be no justification for purchasing a more expensive device when a lower-cost predicate device, which is equivalent, is available.”

Though limited by certain factors such as lack of access to detailed FDA information such as the specific criteria used to determine equivalence, and a lack of published literature on the full market penetration of biological mesh materials vs. nonbiological counterparts, the authors maintained that until evidence demonstrates superiority of biological materials, the expense associated with their use cannot be justified.

This study was supported by the Hudson-Penn Endowment fund at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: The jury is still out on the costs and efficacy of biological mesh implants for abdominal wall hernia repair, and the expense associated with their use cannot be justified at this time, a systematic review of the literature suggested.

Major finding: Available evidence remains insufficient to determine whether cost and clinical benefits exist with the use of biological mesh for abdominal wall hernia repair.

Data source: A systematic review of the literature, yielding 20 eligible studies.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Hudson-Penn Endowment fund at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The authors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.