User login

Despite intravenous medication, a young boy in status epilepticus had the pediatric ICU team at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison stumped. The team called for a consult with the Integrative Medicine Program, which works with licensed acupuncturists and has been affiliated with the department of family medicine since 2001. Acupuncture’s efficacy in this setting has not been validated, but it has been shown to ease chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as radiation-induced xerostomia.1,2

Following several treatments by a licensed acupuncturist and continued conventional care, the boy’s seizures subsided and he was transitioned to the medical floor. Did the acupuncture contribute to bringing the seizures under control? “I can’t say that it was the acupuncture—it was probably a function of all the therapies working together,” says David P. Rakel, MD, assistant professor and director of UW’s Integrative Medicine Program.

The UW case illustrates both current trends and the constant conundrum that surrounds hospital-based complementary medicine: Complementary and alternative medicine’s use is increasing in some U.S. hospitals, yet the existing research evidence for the efficacy of its multiple modalities is decidedly mixed.

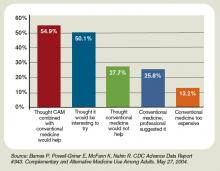

Even if your hospital does not offer complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), your patients are using CAM at ever-increasing rates. In 1993, 34% of Americans reported using some type of CAM (e.g., supplements, massage therapy, prayer, and so on). That number has almost doubled to 62%.3 Americans spend $47 billion a year—of their own money—for CAM therapies, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. And older patients with chronic conditions—the kind of patient hospitalists are most familiar with—tend to try CAM more than younger patients.4

These trends can directly affect hospitalists’ treatment decisions, but they also play a part in how you establish communication and trust with your patients, and how you keep your patients safe from adverse drug interactions. According to the National Academy of Sciences, in order to effectively counsel patients and ensure high-quality comprehensive care, conventional professionals need more CAM-related education.5

—Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, fellow, Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center

What Trends Show

In 2007, according to the American Hospital Association, 20.8% of community hospitals offered some type of care or treatment not based on traditional Western allopathic medicine. That’s up from 8.6% of reporting hospitals that offered those services in 1998.

The 1990s saw rapid growth of integrative medicine centers at major research institutions, and the majority of U.S. cancer centers now offer some form of complementary therapy, says Barrie R. Cassileth, MS, PhD, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Chair in Integrative Medicine and chief of the Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

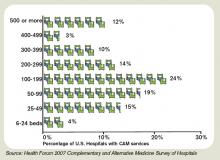

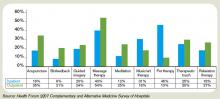

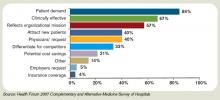

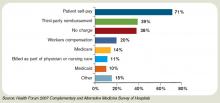

The 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals reported that complementary programs are more common in urban rather than rural hospitals; services vary by hospital size (see Figure 2, above); and the top six modalities offered on an inpatient basis are pet therapy, massage therapy, music/art therapy, guided imagery, acupuncture, and reiki (see “Glossary of Complementary Terms,” above). Eighty-four percent of hospitals offer complementary services due to patient demand, the survey showed.

Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, FHM, SHM board member and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief of the division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, doesn’t see a problem with modalities that can make his patients feel better. Patients at his hospital have access to pet therapy, massage, and acupuncture. “I don’t think these modalities hurt our patients, and there is very little downside, except for potential cost,” says Dr. Li, an SHM board member. “What’s not clear is whether these therapies work or not.”

What’s in a Name?

Numerous therapies and modalities crowd under the CAM umbrella, but most experts classify “complementary” modalities as those used in conjunction with conventional medicine to mitigate symptoms of disease or treatment, whereas “alternative” connotes therapies claiming to treat or cure the underlying disease. Some harmful, dangerous, and dishonest practices fall into the “alternative” category, such as Hulda Clark’s “Zapper” device, which was promoted as a cure for liver flukes, something she says cause everything from diabetes to heart disease. (For more on questionable practices, visit www.quackwatch.com or the National Council Against Health Fraud’s Web site at www.ncahf.org.)

The National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as a group of “diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Dr. Cassileth says the conflation of “complementary and alternative” into one neat acronym—CAM—causes confusion among patients and medical professionals. NCCAM will be changing its name soon, she says, to the National Center for Integrative Medicine, emphasizing the use of adjunctive modalities along with conventional medical treatments.

Hospitalist Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, recently completed a research fellowship at Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center. She explains that integrative medicine uses a macro model of health, claiming a middle ground between the traditional, allopathic model of treating disease.

All Kinds of Evidence

Twenty years of complementary medicine research has yielded some information about safety—namely, what works and what doesn’t. For example, saw palmetto has not panned out as an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia; St. John’s wort, useful for mild depression, interferes with many medications, including cyclosporine and warfarin, and should be avoided at least five days prior to surgery.7,8

Since NCCAM’s inception in October 1998, its research portfolio has stirred debate in the scientific community. Part of the disagreement stems from the difficulty of fitting multidimensional interventions, some of which are provider-dependent (e.g., massage or acupuncture), into the gold standard of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, explains Darshan Mehta, MD, MPH, associate director of medical education at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The manner in which the effectiveness of integrative techniques is assessed requires a higher sophistication of systems research, Dr. Mehta says.

“The way we construe evidence needs to change,” she adds.

Likely to Expand

Most private health plans do not cover complementary services, although Medicare and numerous insurance plans will reimburse treatment in conjunction with physical therapy (e.g., massage) in the outpatient setting. Twenty-three states cover chiropractic care under Medicaid, and Medicare has begun to assess the cost-effectiveness of including acupuncture—especially for postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting—in its benefits package.9 Other modalities, ranging from aromatherapy to guided imagery training, are paid for largely out-of-pocket.10

Dr. Rakel notes that the delivery of integrative medicine services at UW entails conversations with patients about out-of-pocket payments. “It can pose a barrier to the clinician-patient relationship if you give them acupuncture to help with their chemotherapy-induced nausea and then ask for their credit card,” he says.

Hospitalist Preparation

Most complementary therapies are currently offered on an outpatient basis. Because of this trend, and because they deal with acute conditions, hospitalists are less likely to be involved with complementary or integrative medicine services, says Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center hospitalist Andrew C. Ahn, MD, MPH. But that’s not to say complementary medicine is something hospitalists should ignore; patients arrive at the hospital with CAM regimens in tow. It’s the No. 1 reason, Dr. Ahn says, hospitalists should be knowledgeable and exposed to CAM therapies.

Physicians must understand patient patterns and preferences regarding allopathic and complementary medicine, says Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services and optimal healing environments at the Samueli Institute in Alexandria, Va., and author of the 2007 AHA report. She points to a 2006 survey conducted by AARP and NCCAM that found almost 70% of respondents did not tell their physicians about their complementary medicine approaches. These patients are within the age range most likely to be cared for by hospitalists, and failure to communicate about complementary treatment, such as supplemental vitamin use, could lead to safety issues. Moreover, without complete disclosure, the patient-physician relationship might not be as open as possible, Dr. Ananth says.

Many acute-care hospitalists do not have formal dietary supplement policies, and less than half of U.S. children’s hospitals require documentation of a check for drug or dietary supplement interaction.11,12 As a safety issue, it is always incumbent on hospitalists, says Dr. Li, to ask about any supplements or therapies patients are trying on their own as part of the history and physical examination. The policy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. Cassileth says, is that patients on chemotherapy or who are undergoing radiation or facing surgery must avoid herbal dietary supplements.

Beyond Safety

Dr. Bertisch advises hospitalists to pose questions about complementary therapies in an open manner, avoiding antagonistic discussions. “Even when I disagree, I try to guide them to issues about safety and nonsafety, and coax in my concerns,” she says. “The most challenging part about complementary medicine is that patients’ beliefs in these therapies may be so strong that even if the doctor says it won’t work, that will not necessarily change that belief.” A 2001 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine revealed that 70% of respondents would continue to take supplements even if a major study or their physician told them they didn’t work.13

The attraction to complementary medicine often reflects patients’ preferences for a holistic approach to health, says Dr. Ahn, or it may emanate from traditions carried with them from their country of origin. “Once you do understand their reasons for using CAM, then the patient-physician relationship can be significantly strengthened,” he says. With nearly two-thirds of Americans using some form of CAM, hospitalists need to engage in this dialogue.

Dr. Rakel agrees understanding patient culture is vital to uncovering useful information. “Most clinicians would agree that if we can match a therapy to the patient culture and belief system, we are more likely to get buy-in from the patient,” he says.

Dr. Mehta also is a clinical instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He teaches his residents to educate themselves about credentialing, certification, and licensure of complementary providers. He also asks them to maintain an open mind. He says the most important preparation for hospitalists right now is to help educate their patients to be more proactive in their own healthcare. “An engaged patient,” he says, “is better than a disengaged patient.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Deng G, Cassileth BR, Yeung KS. Complementary therapies for cancer-related symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(5):419-426.

- Kahn ST, Johnstone PA. Management of xerostomia related to radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Oncology. 2005;19(14):1827-1832.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;27(343):1-19.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569-1575.

- Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2005.

- Ananth S. 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals. Health Forum LLC. 2008.

- Bent S, Kane C, Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):557-566.

- Bauer BA. The herbal hospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2006;10(2);16-17.

- Ananth S. Applying integrative healthcare. Explore. 2009;5(2):119-120.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-52

- Bassie KL, Witmer DR, Pinto B, Bush C, Clark J, Deffenbaugh J Jr. National survey of dietary supplement policies in acute care facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(1):65-70.

- Gardiner P, Phillips RS, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Henlon S, Woolf AD. Dietary supplements: inpatient policies in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e775-781.

- Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):805-810.

Top Image Source: TETRA IMAGES

Despite intravenous medication, a young boy in status epilepticus had the pediatric ICU team at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison stumped. The team called for a consult with the Integrative Medicine Program, which works with licensed acupuncturists and has been affiliated with the department of family medicine since 2001. Acupuncture’s efficacy in this setting has not been validated, but it has been shown to ease chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as radiation-induced xerostomia.1,2

Following several treatments by a licensed acupuncturist and continued conventional care, the boy’s seizures subsided and he was transitioned to the medical floor. Did the acupuncture contribute to bringing the seizures under control? “I can’t say that it was the acupuncture—it was probably a function of all the therapies working together,” says David P. Rakel, MD, assistant professor and director of UW’s Integrative Medicine Program.

The UW case illustrates both current trends and the constant conundrum that surrounds hospital-based complementary medicine: Complementary and alternative medicine’s use is increasing in some U.S. hospitals, yet the existing research evidence for the efficacy of its multiple modalities is decidedly mixed.

Even if your hospital does not offer complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), your patients are using CAM at ever-increasing rates. In 1993, 34% of Americans reported using some type of CAM (e.g., supplements, massage therapy, prayer, and so on). That number has almost doubled to 62%.3 Americans spend $47 billion a year—of their own money—for CAM therapies, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. And older patients with chronic conditions—the kind of patient hospitalists are most familiar with—tend to try CAM more than younger patients.4

These trends can directly affect hospitalists’ treatment decisions, but they also play a part in how you establish communication and trust with your patients, and how you keep your patients safe from adverse drug interactions. According to the National Academy of Sciences, in order to effectively counsel patients and ensure high-quality comprehensive care, conventional professionals need more CAM-related education.5

—Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, fellow, Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center

What Trends Show

In 2007, according to the American Hospital Association, 20.8% of community hospitals offered some type of care or treatment not based on traditional Western allopathic medicine. That’s up from 8.6% of reporting hospitals that offered those services in 1998.

The 1990s saw rapid growth of integrative medicine centers at major research institutions, and the majority of U.S. cancer centers now offer some form of complementary therapy, says Barrie R. Cassileth, MS, PhD, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Chair in Integrative Medicine and chief of the Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

The 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals reported that complementary programs are more common in urban rather than rural hospitals; services vary by hospital size (see Figure 2, above); and the top six modalities offered on an inpatient basis are pet therapy, massage therapy, music/art therapy, guided imagery, acupuncture, and reiki (see “Glossary of Complementary Terms,” above). Eighty-four percent of hospitals offer complementary services due to patient demand, the survey showed.

Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, FHM, SHM board member and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief of the division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, doesn’t see a problem with modalities that can make his patients feel better. Patients at his hospital have access to pet therapy, massage, and acupuncture. “I don’t think these modalities hurt our patients, and there is very little downside, except for potential cost,” says Dr. Li, an SHM board member. “What’s not clear is whether these therapies work or not.”

What’s in a Name?

Numerous therapies and modalities crowd under the CAM umbrella, but most experts classify “complementary” modalities as those used in conjunction with conventional medicine to mitigate symptoms of disease or treatment, whereas “alternative” connotes therapies claiming to treat or cure the underlying disease. Some harmful, dangerous, and dishonest practices fall into the “alternative” category, such as Hulda Clark’s “Zapper” device, which was promoted as a cure for liver flukes, something she says cause everything from diabetes to heart disease. (For more on questionable practices, visit www.quackwatch.com or the National Council Against Health Fraud’s Web site at www.ncahf.org.)

The National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as a group of “diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Dr. Cassileth says the conflation of “complementary and alternative” into one neat acronym—CAM—causes confusion among patients and medical professionals. NCCAM will be changing its name soon, she says, to the National Center for Integrative Medicine, emphasizing the use of adjunctive modalities along with conventional medical treatments.

Hospitalist Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, recently completed a research fellowship at Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center. She explains that integrative medicine uses a macro model of health, claiming a middle ground between the traditional, allopathic model of treating disease.

All Kinds of Evidence

Twenty years of complementary medicine research has yielded some information about safety—namely, what works and what doesn’t. For example, saw palmetto has not panned out as an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia; St. John’s wort, useful for mild depression, interferes with many medications, including cyclosporine and warfarin, and should be avoided at least five days prior to surgery.7,8

Since NCCAM’s inception in October 1998, its research portfolio has stirred debate in the scientific community. Part of the disagreement stems from the difficulty of fitting multidimensional interventions, some of which are provider-dependent (e.g., massage or acupuncture), into the gold standard of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, explains Darshan Mehta, MD, MPH, associate director of medical education at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The manner in which the effectiveness of integrative techniques is assessed requires a higher sophistication of systems research, Dr. Mehta says.

“The way we construe evidence needs to change,” she adds.

Likely to Expand

Most private health plans do not cover complementary services, although Medicare and numerous insurance plans will reimburse treatment in conjunction with physical therapy (e.g., massage) in the outpatient setting. Twenty-three states cover chiropractic care under Medicaid, and Medicare has begun to assess the cost-effectiveness of including acupuncture—especially for postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting—in its benefits package.9 Other modalities, ranging from aromatherapy to guided imagery training, are paid for largely out-of-pocket.10

Dr. Rakel notes that the delivery of integrative medicine services at UW entails conversations with patients about out-of-pocket payments. “It can pose a barrier to the clinician-patient relationship if you give them acupuncture to help with their chemotherapy-induced nausea and then ask for their credit card,” he says.

Hospitalist Preparation

Most complementary therapies are currently offered on an outpatient basis. Because of this trend, and because they deal with acute conditions, hospitalists are less likely to be involved with complementary or integrative medicine services, says Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center hospitalist Andrew C. Ahn, MD, MPH. But that’s not to say complementary medicine is something hospitalists should ignore; patients arrive at the hospital with CAM regimens in tow. It’s the No. 1 reason, Dr. Ahn says, hospitalists should be knowledgeable and exposed to CAM therapies.

Physicians must understand patient patterns and preferences regarding allopathic and complementary medicine, says Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services and optimal healing environments at the Samueli Institute in Alexandria, Va., and author of the 2007 AHA report. She points to a 2006 survey conducted by AARP and NCCAM that found almost 70% of respondents did not tell their physicians about their complementary medicine approaches. These patients are within the age range most likely to be cared for by hospitalists, and failure to communicate about complementary treatment, such as supplemental vitamin use, could lead to safety issues. Moreover, without complete disclosure, the patient-physician relationship might not be as open as possible, Dr. Ananth says.

Many acute-care hospitalists do not have formal dietary supplement policies, and less than half of U.S. children’s hospitals require documentation of a check for drug or dietary supplement interaction.11,12 As a safety issue, it is always incumbent on hospitalists, says Dr. Li, to ask about any supplements or therapies patients are trying on their own as part of the history and physical examination. The policy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. Cassileth says, is that patients on chemotherapy or who are undergoing radiation or facing surgery must avoid herbal dietary supplements.

Beyond Safety

Dr. Bertisch advises hospitalists to pose questions about complementary therapies in an open manner, avoiding antagonistic discussions. “Even when I disagree, I try to guide them to issues about safety and nonsafety, and coax in my concerns,” she says. “The most challenging part about complementary medicine is that patients’ beliefs in these therapies may be so strong that even if the doctor says it won’t work, that will not necessarily change that belief.” A 2001 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine revealed that 70% of respondents would continue to take supplements even if a major study or their physician told them they didn’t work.13

The attraction to complementary medicine often reflects patients’ preferences for a holistic approach to health, says Dr. Ahn, or it may emanate from traditions carried with them from their country of origin. “Once you do understand their reasons for using CAM, then the patient-physician relationship can be significantly strengthened,” he says. With nearly two-thirds of Americans using some form of CAM, hospitalists need to engage in this dialogue.

Dr. Rakel agrees understanding patient culture is vital to uncovering useful information. “Most clinicians would agree that if we can match a therapy to the patient culture and belief system, we are more likely to get buy-in from the patient,” he says.

Dr. Mehta also is a clinical instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He teaches his residents to educate themselves about credentialing, certification, and licensure of complementary providers. He also asks them to maintain an open mind. He says the most important preparation for hospitalists right now is to help educate their patients to be more proactive in their own healthcare. “An engaged patient,” he says, “is better than a disengaged patient.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Deng G, Cassileth BR, Yeung KS. Complementary therapies for cancer-related symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(5):419-426.

- Kahn ST, Johnstone PA. Management of xerostomia related to radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Oncology. 2005;19(14):1827-1832.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;27(343):1-19.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569-1575.

- Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2005.

- Ananth S. 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals. Health Forum LLC. 2008.

- Bent S, Kane C, Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):557-566.

- Bauer BA. The herbal hospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2006;10(2);16-17.

- Ananth S. Applying integrative healthcare. Explore. 2009;5(2):119-120.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-52

- Bassie KL, Witmer DR, Pinto B, Bush C, Clark J, Deffenbaugh J Jr. National survey of dietary supplement policies in acute care facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(1):65-70.

- Gardiner P, Phillips RS, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Henlon S, Woolf AD. Dietary supplements: inpatient policies in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e775-781.

- Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):805-810.

Top Image Source: TETRA IMAGES

Despite intravenous medication, a young boy in status epilepticus had the pediatric ICU team at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison stumped. The team called for a consult with the Integrative Medicine Program, which works with licensed acupuncturists and has been affiliated with the department of family medicine since 2001. Acupuncture’s efficacy in this setting has not been validated, but it has been shown to ease chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as radiation-induced xerostomia.1,2

Following several treatments by a licensed acupuncturist and continued conventional care, the boy’s seizures subsided and he was transitioned to the medical floor. Did the acupuncture contribute to bringing the seizures under control? “I can’t say that it was the acupuncture—it was probably a function of all the therapies working together,” says David P. Rakel, MD, assistant professor and director of UW’s Integrative Medicine Program.

The UW case illustrates both current trends and the constant conundrum that surrounds hospital-based complementary medicine: Complementary and alternative medicine’s use is increasing in some U.S. hospitals, yet the existing research evidence for the efficacy of its multiple modalities is decidedly mixed.

Even if your hospital does not offer complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), your patients are using CAM at ever-increasing rates. In 1993, 34% of Americans reported using some type of CAM (e.g., supplements, massage therapy, prayer, and so on). That number has almost doubled to 62%.3 Americans spend $47 billion a year—of their own money—for CAM therapies, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. And older patients with chronic conditions—the kind of patient hospitalists are most familiar with—tend to try CAM more than younger patients.4

These trends can directly affect hospitalists’ treatment decisions, but they also play a part in how you establish communication and trust with your patients, and how you keep your patients safe from adverse drug interactions. According to the National Academy of Sciences, in order to effectively counsel patients and ensure high-quality comprehensive care, conventional professionals need more CAM-related education.5

—Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, fellow, Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center

What Trends Show

In 2007, according to the American Hospital Association, 20.8% of community hospitals offered some type of care or treatment not based on traditional Western allopathic medicine. That’s up from 8.6% of reporting hospitals that offered those services in 1998.

The 1990s saw rapid growth of integrative medicine centers at major research institutions, and the majority of U.S. cancer centers now offer some form of complementary therapy, says Barrie R. Cassileth, MS, PhD, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Chair in Integrative Medicine and chief of the Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

The 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals reported that complementary programs are more common in urban rather than rural hospitals; services vary by hospital size (see Figure 2, above); and the top six modalities offered on an inpatient basis are pet therapy, massage therapy, music/art therapy, guided imagery, acupuncture, and reiki (see “Glossary of Complementary Terms,” above). Eighty-four percent of hospitals offer complementary services due to patient demand, the survey showed.

Joseph Ming-Wah Li, MD, FHM, SHM board member and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief of the division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, doesn’t see a problem with modalities that can make his patients feel better. Patients at his hospital have access to pet therapy, massage, and acupuncture. “I don’t think these modalities hurt our patients, and there is very little downside, except for potential cost,” says Dr. Li, an SHM board member. “What’s not clear is whether these therapies work or not.”

What’s in a Name?

Numerous therapies and modalities crowd under the CAM umbrella, but most experts classify “complementary” modalities as those used in conjunction with conventional medicine to mitigate symptoms of disease or treatment, whereas “alternative” connotes therapies claiming to treat or cure the underlying disease. Some harmful, dangerous, and dishonest practices fall into the “alternative” category, such as Hulda Clark’s “Zapper” device, which was promoted as a cure for liver flukes, something she says cause everything from diabetes to heart disease. (For more on questionable practices, visit www.quackwatch.com or the National Council Against Health Fraud’s Web site at www.ncahf.org.)

The National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as a group of “diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.” Dr. Cassileth says the conflation of “complementary and alternative” into one neat acronym—CAM—causes confusion among patients and medical professionals. NCCAM will be changing its name soon, she says, to the National Center for Integrative Medicine, emphasizing the use of adjunctive modalities along with conventional medical treatments.

Hospitalist Suzanne Bertisch, MD, MPH, recently completed a research fellowship at Harvard Medical School’s Osher Research Center. She explains that integrative medicine uses a macro model of health, claiming a middle ground between the traditional, allopathic model of treating disease.

All Kinds of Evidence

Twenty years of complementary medicine research has yielded some information about safety—namely, what works and what doesn’t. For example, saw palmetto has not panned out as an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia; St. John’s wort, useful for mild depression, interferes with many medications, including cyclosporine and warfarin, and should be avoided at least five days prior to surgery.7,8

Since NCCAM’s inception in October 1998, its research portfolio has stirred debate in the scientific community. Part of the disagreement stems from the difficulty of fitting multidimensional interventions, some of which are provider-dependent (e.g., massage or acupuncture), into the gold standard of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, explains Darshan Mehta, MD, MPH, associate director of medical education at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The manner in which the effectiveness of integrative techniques is assessed requires a higher sophistication of systems research, Dr. Mehta says.

“The way we construe evidence needs to change,” she adds.

Likely to Expand

Most private health plans do not cover complementary services, although Medicare and numerous insurance plans will reimburse treatment in conjunction with physical therapy (e.g., massage) in the outpatient setting. Twenty-three states cover chiropractic care under Medicaid, and Medicare has begun to assess the cost-effectiveness of including acupuncture—especially for postoperative and chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting—in its benefits package.9 Other modalities, ranging from aromatherapy to guided imagery training, are paid for largely out-of-pocket.10

Dr. Rakel notes that the delivery of integrative medicine services at UW entails conversations with patients about out-of-pocket payments. “It can pose a barrier to the clinician-patient relationship if you give them acupuncture to help with their chemotherapy-induced nausea and then ask for their credit card,” he says.

Hospitalist Preparation

Most complementary therapies are currently offered on an outpatient basis. Because of this trend, and because they deal with acute conditions, hospitalists are less likely to be involved with complementary or integrative medicine services, says Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center hospitalist Andrew C. Ahn, MD, MPH. But that’s not to say complementary medicine is something hospitalists should ignore; patients arrive at the hospital with CAM regimens in tow. It’s the No. 1 reason, Dr. Ahn says, hospitalists should be knowledgeable and exposed to CAM therapies.

Physicians must understand patient patterns and preferences regarding allopathic and complementary medicine, says Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services and optimal healing environments at the Samueli Institute in Alexandria, Va., and author of the 2007 AHA report. She points to a 2006 survey conducted by AARP and NCCAM that found almost 70% of respondents did not tell their physicians about their complementary medicine approaches. These patients are within the age range most likely to be cared for by hospitalists, and failure to communicate about complementary treatment, such as supplemental vitamin use, could lead to safety issues. Moreover, without complete disclosure, the patient-physician relationship might not be as open as possible, Dr. Ananth says.

Many acute-care hospitalists do not have formal dietary supplement policies, and less than half of U.S. children’s hospitals require documentation of a check for drug or dietary supplement interaction.11,12 As a safety issue, it is always incumbent on hospitalists, says Dr. Li, to ask about any supplements or therapies patients are trying on their own as part of the history and physical examination. The policy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. Cassileth says, is that patients on chemotherapy or who are undergoing radiation or facing surgery must avoid herbal dietary supplements.

Beyond Safety

Dr. Bertisch advises hospitalists to pose questions about complementary therapies in an open manner, avoiding antagonistic discussions. “Even when I disagree, I try to guide them to issues about safety and nonsafety, and coax in my concerns,” she says. “The most challenging part about complementary medicine is that patients’ beliefs in these therapies may be so strong that even if the doctor says it won’t work, that will not necessarily change that belief.” A 2001 study in the Archives of Internal Medicine revealed that 70% of respondents would continue to take supplements even if a major study or their physician told them they didn’t work.13

The attraction to complementary medicine often reflects patients’ preferences for a holistic approach to health, says Dr. Ahn, or it may emanate from traditions carried with them from their country of origin. “Once you do understand their reasons for using CAM, then the patient-physician relationship can be significantly strengthened,” he says. With nearly two-thirds of Americans using some form of CAM, hospitalists need to engage in this dialogue.

Dr. Rakel agrees understanding patient culture is vital to uncovering useful information. “Most clinicians would agree that if we can match a therapy to the patient culture and belief system, we are more likely to get buy-in from the patient,” he says.

Dr. Mehta also is a clinical instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He teaches his residents to educate themselves about credentialing, certification, and licensure of complementary providers. He also asks them to maintain an open mind. He says the most important preparation for hospitalists right now is to help educate their patients to be more proactive in their own healthcare. “An engaged patient,” he says, “is better than a disengaged patient.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Deng G, Cassileth BR, Yeung KS. Complementary therapies for cancer-related symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(5):419-426.

- Kahn ST, Johnstone PA. Management of xerostomia related to radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Oncology. 2005;19(14):1827-1832.

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;27(343):1-19.

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569-1575.

- Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2005.

- Ananth S. 2007 Health Forum/AHA Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals. Health Forum LLC. 2008.

- Bent S, Kane C, Shinohara K, et al. Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):557-566.

- Bauer BA. The herbal hospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2006;10(2);16-17.

- Ananth S. Applying integrative healthcare. Explore. 2009;5(2):119-120.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246-52

- Bassie KL, Witmer DR, Pinto B, Bush C, Clark J, Deffenbaugh J Jr. National survey of dietary supplement policies in acute care facilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(1):65-70.

- Gardiner P, Phillips RS, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Henlon S, Woolf AD. Dietary supplements: inpatient policies in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e775-781.

- Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):805-810.

Top Image Source: TETRA IMAGES