User login

In 1980 women physicians represented 11.6% of all U.S. physicians. In 2003 they represented 26% of the total physician population.1 Drawing from the ranks of internal medicine and pediatrics, in which women physicians represent 41.8% and 65.6% of all residents, hospital medicine will likely reap the benefits of these increasing numbers.2 Indeed, hospital medicine appears to offer many advantages for women: an intrinsically collaborative working environment, flexible work hours, and the opportunity to participate in forming the structure for a new specialty. But do enough opportunities for advancement exist in this relatively young specialty?

The Hospitalist recently talked with women hospitalists, SHM leadership, and a researcher on gender discrimination in academic medicine. All shared their perceptions about how hospital medicine fares regarding inclusion of women—both in the ranks and in leadership positions.

A Career that Works

“As a woman hospitalist, I’ve had many opportunities to advocate for patient safety and quality being the primary guiding principle in reorganizing care,” says Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, associate chair, Department of Internal Medicine and an academic hospitalist at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, Mich. “I think as women we do juggle a lot of responsibilities, but I think those skills probably uniquely position us to be very effective in managing groups and being members and leaders of teams.”

As a mother of two young children, Dr. Halasyamani enjoys the flexibility of her current position. “I have a very busy life, but I make sure I have time to do the other parts of my life because those will never come back to me. Today, I went to my daughter’s school and helped her class with some of their math problems, and I chair a multicultural committee at her school as well.”

She finds that she brings the same type of organizational skills to both her working and family life. “Whether it’s preparing for a school assembly or preparing for a patient safety committee meeting,” explains Dr. Halasyamani, “there just isn’t time to focus on what is not important or to come unprepared. Every minute is incredibly precious.”

Like Dr. Halasyamani, Sheri Chernetsky Tejedor, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, has also been able to carve out a clinical and academic track that suits her present needs for family time. Under a supportive supervisor, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and director, Emory Hospital Medicine Unit, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Tejedor has worked part time as a hospitalist in a nearby community hospital; has worked in academia, including writing and research in quality improvement; and essentially has been a full-time mother when she is home. “I haven’t felt that any doors have closed, and the only ones that have closed are ones that I’ve closed myself—just accepting that I can’t do everything,” says Dr. Tejedor.

According to the AMA, 62.6% of all women physicians fall within the specialties of internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, and anesthesiology.1 That is one reason the numbers of women in hospital medicine are also increasing, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, CEO of SHM.

“Because hospitalists come from the ranks of pediatricians and internists, as those specialties attract more women, I think they will also find hospital medicine very attractive as they are looking for their career choice,” says Dr. Wellikson.

—Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD

Approaching Parity?

Although SHM does not currently keep statistics on percentages of women in the organization, many hospitalist services point to increasing numbers of women in their departments. For instance, SHM Past President Robert Wachter, MD, FACP, director of the hospitalist group at the University of California, San Francisco, reports that 57% (12 out of 21) of the hospitalists in his group are women. This majority does not stem from deliberate recruiting on his part.

“My goal here has been to recruit and retain the best people. I couldn’t care less whether they are women or men,” says Dr. Wachter. “I would begin to care if we were so skewed in one direction or the other that it might indicate that we weren’t providing a positive environment for either women or men. But our group has grown organically and it has just turned out that we’ve ended up with more women than men.”

Leadership Opportunities in Medicine

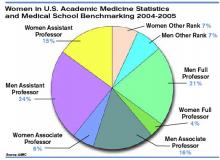

While overall increases in the numbers of women physicians can be seen as a hopeful sign, these percentages may mask the reality for women trying to achieve parity in leadership roles. In fact, the percentages of women in leadership positions in academic medicine remain low: For example, only 11% of department chairs in medical schools are women, and 10% of medical school deans are women.1

A higher percentage of women in a particular specialty does not necessarily translate into better advancement opportunities, according to statistician Arlene S. Ash, PhD, a research professor in the Department of General Internal Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Sadly,” she says, “the main thing you can predict about a specialty with more women is that it will be less well-paid overall.”

Many committee assignments and semi-leadership positions in the academic medicine arena are informally awarded, and they often go to men. “Often these are innocent decisions,” explains Dr. Ash. “The positions carry perks, and perhaps some regular funding, and can be stepping stones to later promotion, but they usually go to the person who pops into the mind of the administrator making the decision.”

It takes “incredible vigilance,” says Dr. Ash, “to see your way past the prejudiced lens with which we all, having grown up in this society, view the relative value of men’s and women’s contributions.”

To achieve more parity for women, Dr. Ash believes it’s necessary to more closely scrutinize and to set standards for leadership selection processes. Currently, she explains, “There is no comprehensive attempt to cast a wide net, to consider all who might be appropriate, and to ensure a non-sexist, non-biased process for choosing people to get such positions. Even in departments with more than 50% women, and even where the problem is recognized, most of these ‘gateway’ opportunities still go to guys.”

Hospitalists Breaking the Mold?

Those interviewed believe hospital medicine, as a new specialty, may have a chance to break the traditional molds established by more entrenched medical school specialties.

“We’re inventing this entire thing [the hospital medicine specialty] as we go along, so we have not had time to develop an ‘old boys’ network,’” quips Dr. Wachter. “The hope is that if you start a field now, it will not develop along those lines. As we look at those holding leadership roles at individual hospitals and in the society, you find that talented people rise to the top. If you start with a neutral playing field without the tradition and history of the smoke-filled room, it turns out that people sort out on their skills and their interests.”

“I think hospital medicine is a very accessible profession for women on a number of levels,” says Dr. Wellikson. “This is a young, growing, evolving field—as opposed to some of the more static fields in medicine, like orthopedics or thoracic surgery. One of the hallmarks of hospital medicine is creating true teams of health professionals. Women come in as equals, with good ideas, and I think this is mirrored on the SHM Board.”

Currently, four of the 12 SHM board members are women; Jean Huddleston, MD, of the Mayo Clinic is a past president; and the incoming president, Mary Jo Gorman, MD, of IPC, is also a woman. “We [the Society of Hospital Medicine] are very much an open tent,” remarks Dr. Wellikson.

According to Sylvia Cheney McKean, MD, FACP, medical director of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service in Boston, there are pros and cons to hospital medicine being a new specialty.

“In some ways, because [hospital medicine] is a new specialty, women may have been given the opportunity to lead hospitalist programs because early hospitalist services—at least initially—were viewed as experimental,” she says. “Many hospital leaders hired hospitalists to function as ‘super residents’ rather than as leaders. So, therefore, academic institutions didn’t really feel that they had much to lose by hiring women versus men, and many hospitalist leaders—male and female—found themselves functioning as middle managers without necessarily having much input into their job descriptions.

“Even in 2006 some physician administrators hire hospitalists with the expectation that turnover is inevitable as physicians advance to other specialties,” continues Dr. McKean. “Hospital administrators and residency directors may not understand the evolving role of hospitalists as change agents in the hospital setting and may not recognize that hospitalists offer special expertise in addition to on-site availability. So it’s a two-edged sword. A lot of hospital medicine programs, because they have not only young physician leaders, but also proportionately more female physician leaders, may find that they really cannot have the same amount of clout as other established specialties within the department of medicine hierarchy.”

Dr. Halasyamani believes that the male hierarchy may be changing. In hospital medicine, she notes, “because the emphasis in inpatient care delivery is so team focused, the leaders in hospital medicine who are able to best meet those goals and have those skills are really the ones who are being given the most opportunity. If the structures within organizations are very hierarchical, then care delivery ends up looking that way. But if the leadership and decision-making structures are more collaborative, then I think care reflects that.”

At her institution, Dr. Halasyamani has had numerous opportunities to help build some of those new structures. For example, in the past year, she helped form an institutional quality and patient safety collaborative practice team, which she chaired jointly with the head of nursing. The team “brings together people who touch the patient; they identify the barriers in delivering the type of care that we want to be proud of every time, and to help solve those problems.”

Possible Pitfalls

Can hospital medicine, in fact, succeed in developing new leadership paradigms? Much will depend on consciously constructing new systems for nurturing talent and leaders. “You really have to think through your mechanisms for recognizing and rewarding achievement and ask if those mechanisms encourage the behaviors you want to encourage, or do they disadvantage people who do the work that you most want done?” says Dr. Ash.

For example, she says, the collaborative nature of hospital medicine can create problems with career advancement. “To do something meaningful, you may need to involve 20 people on a five-year project,” she explains. “How do you ensure that those people don’t get punished for choosing that work?”

Dr. Ash, together with Boston University colleague Phyllis L. Carr, MD, and Linda Pololi, MD, from Brandeis University (the principal investigator) has started a Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation-funded project to “try to change the culture of academic medicine so that it will better encourage and reward collaborative research,” she says. “This change should benefit the entire academic enterprise—although its immediate goal is to make a common career track for women more viable.

“I want to fix a generic problem about the failure to reward certain kinds of highly desirable activities,” says Dr. Ash. “The current reward system hurts women more than men, but I’m not the slightest bit unhappy—it would be a wonderful thing, actually—for men who do collaborative research to also get the career benefits they deserve.”

Advice for Leaders and Women

Are opportunities for women hospitalists improving? Dr. McKean thinks that “hierarchies exist in hospitals, where surgeons are more powerful than physicians in the department of medicine, which has its own internal hierarchy. I see many more women interviewing for internal medicine slots. And, you could say, that’s great, it’s equalizing out. But I wonder if all it’s going to mean is that the pay scale will go down. I think that’s a real consideration. What we’re seeing now is that the starting salary for physician assistants in the hospital may be more than the starting salary for some physicians in primary care. Adding more women [to a specialty] may not change inequalities. The key is adding more women in the highest leadership positions.”

“The whole process of growing talent needs to be done in a take-control sort of way,” says Dr. Ash. There is a predictable, ongoing need to fill leadership positions, she notes, and “not enough good thought about how to systematically reach out to the entire potential talent pool.”

“Mentorship is very important,” emphasizes Dr. McKean. Her own career as a physician was characterized early on, she says, by a lack of support and mentorship. Twenty-five years later, she hopes things are beginning to change and hospital medicine may in fact set the standard for other specialties for both male and female physicians.

“Medicine is always going to be unpredictable,” she continues. “It will always be stressful. There will be acutely ill patients, and people will return [to the hospital] with unanticipated problems. You cannot change this reality. But you can change how things are structured. The more the Society of Hospital Medicine can give people the tools to identify modifiable risk factors in their own practices, help leaders of the hospitalist services analyze what works and what doesn’t work, and allow for as much diversity as possible within each service, I think that a career in hospital medicine will be sustainable and extremely satisfying, and that people will get promoted. They will find different niches in which they are expert.”

To that end, with Win Whitcomb, MD (SHM co-founder), Dr. McKean approached the SHM to charge a task force to identify what makes for a long and satisfying career in hospital medicine and to develop practice standards. The job-person fit is important, and she advises young women hospitalists to take a look at themselves, define what is important, and then “tailor a schedule around that. If it is important to you to be teaching residents, for example, then you need to be in an academic program. If it is more important to have time off, and to work shifts, then you might want to work at a community hospital. There are a lot of different models,” she says “so you have to look at yourself and your husband and the other issues you have to grapple with in addition to your career.”

Above all Dr. McKean urges women (as well as men) to be receptive to advocates or mentors within their organizations.

Going Forward

Overall, Dr. Wachter sees “the nature of the field [of hospital medicine] as one that involves a lot of collaboration and multidisciplinary work seems to draw a certain kind of person. The kind of person who is most happy and successful in our field is one who likes working closely with nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and hospital administrators, and recognizes that the quality of care and patients’ outcomes are going to be, in large part, dependent on how well that team functions.”

Many younger women and men hospitalists are finding that the job-person fit contributes to a fulfilling work/life balance.

“I chose this field because I was interested in inpatient care,” says Dr. Tejedor, and the flexibility offered by her institution has reinforced that choice. “This [hospital medicine] is a great way to have the best of everything.” TH

Writer Gretchen Henkel is based in California.

References

- Women in Medicine Statistics. Prepared by the Women Physicians Congress from Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US, 2005 ed., Chicago. AMA Press. Available at www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/19/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.

- Table 2. Distribution of Residents by Specialty, 1994 Compared to 2004. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Medical School Benchmarking, 2004-2005. Association of American Medical Colleges; page 12. Available at www.aamc.org/members/wim/statistics/stats05/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.

In 1980 women physicians represented 11.6% of all U.S. physicians. In 2003 they represented 26% of the total physician population.1 Drawing from the ranks of internal medicine and pediatrics, in which women physicians represent 41.8% and 65.6% of all residents, hospital medicine will likely reap the benefits of these increasing numbers.2 Indeed, hospital medicine appears to offer many advantages for women: an intrinsically collaborative working environment, flexible work hours, and the opportunity to participate in forming the structure for a new specialty. But do enough opportunities for advancement exist in this relatively young specialty?

The Hospitalist recently talked with women hospitalists, SHM leadership, and a researcher on gender discrimination in academic medicine. All shared their perceptions about how hospital medicine fares regarding inclusion of women—both in the ranks and in leadership positions.

A Career that Works

“As a woman hospitalist, I’ve had many opportunities to advocate for patient safety and quality being the primary guiding principle in reorganizing care,” says Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, associate chair, Department of Internal Medicine and an academic hospitalist at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, Mich. “I think as women we do juggle a lot of responsibilities, but I think those skills probably uniquely position us to be very effective in managing groups and being members and leaders of teams.”

As a mother of two young children, Dr. Halasyamani enjoys the flexibility of her current position. “I have a very busy life, but I make sure I have time to do the other parts of my life because those will never come back to me. Today, I went to my daughter’s school and helped her class with some of their math problems, and I chair a multicultural committee at her school as well.”

She finds that she brings the same type of organizational skills to both her working and family life. “Whether it’s preparing for a school assembly or preparing for a patient safety committee meeting,” explains Dr. Halasyamani, “there just isn’t time to focus on what is not important or to come unprepared. Every minute is incredibly precious.”

Like Dr. Halasyamani, Sheri Chernetsky Tejedor, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, has also been able to carve out a clinical and academic track that suits her present needs for family time. Under a supportive supervisor, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and director, Emory Hospital Medicine Unit, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Tejedor has worked part time as a hospitalist in a nearby community hospital; has worked in academia, including writing and research in quality improvement; and essentially has been a full-time mother when she is home. “I haven’t felt that any doors have closed, and the only ones that have closed are ones that I’ve closed myself—just accepting that I can’t do everything,” says Dr. Tejedor.

According to the AMA, 62.6% of all women physicians fall within the specialties of internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, and anesthesiology.1 That is one reason the numbers of women in hospital medicine are also increasing, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, CEO of SHM.

“Because hospitalists come from the ranks of pediatricians and internists, as those specialties attract more women, I think they will also find hospital medicine very attractive as they are looking for their career choice,” says Dr. Wellikson.

—Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD

Approaching Parity?

Although SHM does not currently keep statistics on percentages of women in the organization, many hospitalist services point to increasing numbers of women in their departments. For instance, SHM Past President Robert Wachter, MD, FACP, director of the hospitalist group at the University of California, San Francisco, reports that 57% (12 out of 21) of the hospitalists in his group are women. This majority does not stem from deliberate recruiting on his part.

“My goal here has been to recruit and retain the best people. I couldn’t care less whether they are women or men,” says Dr. Wachter. “I would begin to care if we were so skewed in one direction or the other that it might indicate that we weren’t providing a positive environment for either women or men. But our group has grown organically and it has just turned out that we’ve ended up with more women than men.”

Leadership Opportunities in Medicine

While overall increases in the numbers of women physicians can be seen as a hopeful sign, these percentages may mask the reality for women trying to achieve parity in leadership roles. In fact, the percentages of women in leadership positions in academic medicine remain low: For example, only 11% of department chairs in medical schools are women, and 10% of medical school deans are women.1

A higher percentage of women in a particular specialty does not necessarily translate into better advancement opportunities, according to statistician Arlene S. Ash, PhD, a research professor in the Department of General Internal Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Sadly,” she says, “the main thing you can predict about a specialty with more women is that it will be less well-paid overall.”

Many committee assignments and semi-leadership positions in the academic medicine arena are informally awarded, and they often go to men. “Often these are innocent decisions,” explains Dr. Ash. “The positions carry perks, and perhaps some regular funding, and can be stepping stones to later promotion, but they usually go to the person who pops into the mind of the administrator making the decision.”

It takes “incredible vigilance,” says Dr. Ash, “to see your way past the prejudiced lens with which we all, having grown up in this society, view the relative value of men’s and women’s contributions.”

To achieve more parity for women, Dr. Ash believes it’s necessary to more closely scrutinize and to set standards for leadership selection processes. Currently, she explains, “There is no comprehensive attempt to cast a wide net, to consider all who might be appropriate, and to ensure a non-sexist, non-biased process for choosing people to get such positions. Even in departments with more than 50% women, and even where the problem is recognized, most of these ‘gateway’ opportunities still go to guys.”

Hospitalists Breaking the Mold?

Those interviewed believe hospital medicine, as a new specialty, may have a chance to break the traditional molds established by more entrenched medical school specialties.

“We’re inventing this entire thing [the hospital medicine specialty] as we go along, so we have not had time to develop an ‘old boys’ network,’” quips Dr. Wachter. “The hope is that if you start a field now, it will not develop along those lines. As we look at those holding leadership roles at individual hospitals and in the society, you find that talented people rise to the top. If you start with a neutral playing field without the tradition and history of the smoke-filled room, it turns out that people sort out on their skills and their interests.”

“I think hospital medicine is a very accessible profession for women on a number of levels,” says Dr. Wellikson. “This is a young, growing, evolving field—as opposed to some of the more static fields in medicine, like orthopedics or thoracic surgery. One of the hallmarks of hospital medicine is creating true teams of health professionals. Women come in as equals, with good ideas, and I think this is mirrored on the SHM Board.”

Currently, four of the 12 SHM board members are women; Jean Huddleston, MD, of the Mayo Clinic is a past president; and the incoming president, Mary Jo Gorman, MD, of IPC, is also a woman. “We [the Society of Hospital Medicine] are very much an open tent,” remarks Dr. Wellikson.

According to Sylvia Cheney McKean, MD, FACP, medical director of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service in Boston, there are pros and cons to hospital medicine being a new specialty.

“In some ways, because [hospital medicine] is a new specialty, women may have been given the opportunity to lead hospitalist programs because early hospitalist services—at least initially—were viewed as experimental,” she says. “Many hospital leaders hired hospitalists to function as ‘super residents’ rather than as leaders. So, therefore, academic institutions didn’t really feel that they had much to lose by hiring women versus men, and many hospitalist leaders—male and female—found themselves functioning as middle managers without necessarily having much input into their job descriptions.

“Even in 2006 some physician administrators hire hospitalists with the expectation that turnover is inevitable as physicians advance to other specialties,” continues Dr. McKean. “Hospital administrators and residency directors may not understand the evolving role of hospitalists as change agents in the hospital setting and may not recognize that hospitalists offer special expertise in addition to on-site availability. So it’s a two-edged sword. A lot of hospital medicine programs, because they have not only young physician leaders, but also proportionately more female physician leaders, may find that they really cannot have the same amount of clout as other established specialties within the department of medicine hierarchy.”

Dr. Halasyamani believes that the male hierarchy may be changing. In hospital medicine, she notes, “because the emphasis in inpatient care delivery is so team focused, the leaders in hospital medicine who are able to best meet those goals and have those skills are really the ones who are being given the most opportunity. If the structures within organizations are very hierarchical, then care delivery ends up looking that way. But if the leadership and decision-making structures are more collaborative, then I think care reflects that.”

At her institution, Dr. Halasyamani has had numerous opportunities to help build some of those new structures. For example, in the past year, she helped form an institutional quality and patient safety collaborative practice team, which she chaired jointly with the head of nursing. The team “brings together people who touch the patient; they identify the barriers in delivering the type of care that we want to be proud of every time, and to help solve those problems.”

Possible Pitfalls

Can hospital medicine, in fact, succeed in developing new leadership paradigms? Much will depend on consciously constructing new systems for nurturing talent and leaders. “You really have to think through your mechanisms for recognizing and rewarding achievement and ask if those mechanisms encourage the behaviors you want to encourage, or do they disadvantage people who do the work that you most want done?” says Dr. Ash.

For example, she says, the collaborative nature of hospital medicine can create problems with career advancement. “To do something meaningful, you may need to involve 20 people on a five-year project,” she explains. “How do you ensure that those people don’t get punished for choosing that work?”

Dr. Ash, together with Boston University colleague Phyllis L. Carr, MD, and Linda Pololi, MD, from Brandeis University (the principal investigator) has started a Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation-funded project to “try to change the culture of academic medicine so that it will better encourage and reward collaborative research,” she says. “This change should benefit the entire academic enterprise—although its immediate goal is to make a common career track for women more viable.

“I want to fix a generic problem about the failure to reward certain kinds of highly desirable activities,” says Dr. Ash. “The current reward system hurts women more than men, but I’m not the slightest bit unhappy—it would be a wonderful thing, actually—for men who do collaborative research to also get the career benefits they deserve.”

Advice for Leaders and Women

Are opportunities for women hospitalists improving? Dr. McKean thinks that “hierarchies exist in hospitals, where surgeons are more powerful than physicians in the department of medicine, which has its own internal hierarchy. I see many more women interviewing for internal medicine slots. And, you could say, that’s great, it’s equalizing out. But I wonder if all it’s going to mean is that the pay scale will go down. I think that’s a real consideration. What we’re seeing now is that the starting salary for physician assistants in the hospital may be more than the starting salary for some physicians in primary care. Adding more women [to a specialty] may not change inequalities. The key is adding more women in the highest leadership positions.”

“The whole process of growing talent needs to be done in a take-control sort of way,” says Dr. Ash. There is a predictable, ongoing need to fill leadership positions, she notes, and “not enough good thought about how to systematically reach out to the entire potential talent pool.”

“Mentorship is very important,” emphasizes Dr. McKean. Her own career as a physician was characterized early on, she says, by a lack of support and mentorship. Twenty-five years later, she hopes things are beginning to change and hospital medicine may in fact set the standard for other specialties for both male and female physicians.

“Medicine is always going to be unpredictable,” she continues. “It will always be stressful. There will be acutely ill patients, and people will return [to the hospital] with unanticipated problems. You cannot change this reality. But you can change how things are structured. The more the Society of Hospital Medicine can give people the tools to identify modifiable risk factors in their own practices, help leaders of the hospitalist services analyze what works and what doesn’t work, and allow for as much diversity as possible within each service, I think that a career in hospital medicine will be sustainable and extremely satisfying, and that people will get promoted. They will find different niches in which they are expert.”

To that end, with Win Whitcomb, MD (SHM co-founder), Dr. McKean approached the SHM to charge a task force to identify what makes for a long and satisfying career in hospital medicine and to develop practice standards. The job-person fit is important, and she advises young women hospitalists to take a look at themselves, define what is important, and then “tailor a schedule around that. If it is important to you to be teaching residents, for example, then you need to be in an academic program. If it is more important to have time off, and to work shifts, then you might want to work at a community hospital. There are a lot of different models,” she says “so you have to look at yourself and your husband and the other issues you have to grapple with in addition to your career.”

Above all Dr. McKean urges women (as well as men) to be receptive to advocates or mentors within their organizations.

Going Forward

Overall, Dr. Wachter sees “the nature of the field [of hospital medicine] as one that involves a lot of collaboration and multidisciplinary work seems to draw a certain kind of person. The kind of person who is most happy and successful in our field is one who likes working closely with nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and hospital administrators, and recognizes that the quality of care and patients’ outcomes are going to be, in large part, dependent on how well that team functions.”

Many younger women and men hospitalists are finding that the job-person fit contributes to a fulfilling work/life balance.

“I chose this field because I was interested in inpatient care,” says Dr. Tejedor, and the flexibility offered by her institution has reinforced that choice. “This [hospital medicine] is a great way to have the best of everything.” TH

Writer Gretchen Henkel is based in California.

References

- Women in Medicine Statistics. Prepared by the Women Physicians Congress from Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US, 2005 ed., Chicago. AMA Press. Available at www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/19/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.

- Table 2. Distribution of Residents by Specialty, 1994 Compared to 2004. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Medical School Benchmarking, 2004-2005. Association of American Medical Colleges; page 12. Available at www.aamc.org/members/wim/statistics/stats05/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.

In 1980 women physicians represented 11.6% of all U.S. physicians. In 2003 they represented 26% of the total physician population.1 Drawing from the ranks of internal medicine and pediatrics, in which women physicians represent 41.8% and 65.6% of all residents, hospital medicine will likely reap the benefits of these increasing numbers.2 Indeed, hospital medicine appears to offer many advantages for women: an intrinsically collaborative working environment, flexible work hours, and the opportunity to participate in forming the structure for a new specialty. But do enough opportunities for advancement exist in this relatively young specialty?

The Hospitalist recently talked with women hospitalists, SHM leadership, and a researcher on gender discrimination in academic medicine. All shared their perceptions about how hospital medicine fares regarding inclusion of women—both in the ranks and in leadership positions.

A Career that Works

“As a woman hospitalist, I’ve had many opportunities to advocate for patient safety and quality being the primary guiding principle in reorganizing care,” says Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, associate chair, Department of Internal Medicine and an academic hospitalist at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, Mich. “I think as women we do juggle a lot of responsibilities, but I think those skills probably uniquely position us to be very effective in managing groups and being members and leaders of teams.”

As a mother of two young children, Dr. Halasyamani enjoys the flexibility of her current position. “I have a very busy life, but I make sure I have time to do the other parts of my life because those will never come back to me. Today, I went to my daughter’s school and helped her class with some of their math problems, and I chair a multicultural committee at her school as well.”

She finds that she brings the same type of organizational skills to both her working and family life. “Whether it’s preparing for a school assembly or preparing for a patient safety committee meeting,” explains Dr. Halasyamani, “there just isn’t time to focus on what is not important or to come unprepared. Every minute is incredibly precious.”

Like Dr. Halasyamani, Sheri Chernetsky Tejedor, MD, a clinical instructor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, has also been able to carve out a clinical and academic track that suits her present needs for family time. Under a supportive supervisor, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, professor of medicine and director, Emory Hospital Medicine Unit, and editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Tejedor has worked part time as a hospitalist in a nearby community hospital; has worked in academia, including writing and research in quality improvement; and essentially has been a full-time mother when she is home. “I haven’t felt that any doors have closed, and the only ones that have closed are ones that I’ve closed myself—just accepting that I can’t do everything,” says Dr. Tejedor.

According to the AMA, 62.6% of all women physicians fall within the specialties of internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, and anesthesiology.1 That is one reason the numbers of women in hospital medicine are also increasing, says Larry Wellikson, MD, FACP, CEO of SHM.

“Because hospitalists come from the ranks of pediatricians and internists, as those specialties attract more women, I think they will also find hospital medicine very attractive as they are looking for their career choice,” says Dr. Wellikson.

—Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD

Approaching Parity?

Although SHM does not currently keep statistics on percentages of women in the organization, many hospitalist services point to increasing numbers of women in their departments. For instance, SHM Past President Robert Wachter, MD, FACP, director of the hospitalist group at the University of California, San Francisco, reports that 57% (12 out of 21) of the hospitalists in his group are women. This majority does not stem from deliberate recruiting on his part.

“My goal here has been to recruit and retain the best people. I couldn’t care less whether they are women or men,” says Dr. Wachter. “I would begin to care if we were so skewed in one direction or the other that it might indicate that we weren’t providing a positive environment for either women or men. But our group has grown organically and it has just turned out that we’ve ended up with more women than men.”

Leadership Opportunities in Medicine

While overall increases in the numbers of women physicians can be seen as a hopeful sign, these percentages may mask the reality for women trying to achieve parity in leadership roles. In fact, the percentages of women in leadership positions in academic medicine remain low: For example, only 11% of department chairs in medical schools are women, and 10% of medical school deans are women.1

A higher percentage of women in a particular specialty does not necessarily translate into better advancement opportunities, according to statistician Arlene S. Ash, PhD, a research professor in the Department of General Internal Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Sadly,” she says, “the main thing you can predict about a specialty with more women is that it will be less well-paid overall.”

Many committee assignments and semi-leadership positions in the academic medicine arena are informally awarded, and they often go to men. “Often these are innocent decisions,” explains Dr. Ash. “The positions carry perks, and perhaps some regular funding, and can be stepping stones to later promotion, but they usually go to the person who pops into the mind of the administrator making the decision.”

It takes “incredible vigilance,” says Dr. Ash, “to see your way past the prejudiced lens with which we all, having grown up in this society, view the relative value of men’s and women’s contributions.”

To achieve more parity for women, Dr. Ash believes it’s necessary to more closely scrutinize and to set standards for leadership selection processes. Currently, she explains, “There is no comprehensive attempt to cast a wide net, to consider all who might be appropriate, and to ensure a non-sexist, non-biased process for choosing people to get such positions. Even in departments with more than 50% women, and even where the problem is recognized, most of these ‘gateway’ opportunities still go to guys.”

Hospitalists Breaking the Mold?

Those interviewed believe hospital medicine, as a new specialty, may have a chance to break the traditional molds established by more entrenched medical school specialties.

“We’re inventing this entire thing [the hospital medicine specialty] as we go along, so we have not had time to develop an ‘old boys’ network,’” quips Dr. Wachter. “The hope is that if you start a field now, it will not develop along those lines. As we look at those holding leadership roles at individual hospitals and in the society, you find that talented people rise to the top. If you start with a neutral playing field without the tradition and history of the smoke-filled room, it turns out that people sort out on their skills and their interests.”

“I think hospital medicine is a very accessible profession for women on a number of levels,” says Dr. Wellikson. “This is a young, growing, evolving field—as opposed to some of the more static fields in medicine, like orthopedics or thoracic surgery. One of the hallmarks of hospital medicine is creating true teams of health professionals. Women come in as equals, with good ideas, and I think this is mirrored on the SHM Board.”

Currently, four of the 12 SHM board members are women; Jean Huddleston, MD, of the Mayo Clinic is a past president; and the incoming president, Mary Jo Gorman, MD, of IPC, is also a woman. “We [the Society of Hospital Medicine] are very much an open tent,” remarks Dr. Wellikson.

According to Sylvia Cheney McKean, MD, FACP, medical director of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Service in Boston, there are pros and cons to hospital medicine being a new specialty.

“In some ways, because [hospital medicine] is a new specialty, women may have been given the opportunity to lead hospitalist programs because early hospitalist services—at least initially—were viewed as experimental,” she says. “Many hospital leaders hired hospitalists to function as ‘super residents’ rather than as leaders. So, therefore, academic institutions didn’t really feel that they had much to lose by hiring women versus men, and many hospitalist leaders—male and female—found themselves functioning as middle managers without necessarily having much input into their job descriptions.

“Even in 2006 some physician administrators hire hospitalists with the expectation that turnover is inevitable as physicians advance to other specialties,” continues Dr. McKean. “Hospital administrators and residency directors may not understand the evolving role of hospitalists as change agents in the hospital setting and may not recognize that hospitalists offer special expertise in addition to on-site availability. So it’s a two-edged sword. A lot of hospital medicine programs, because they have not only young physician leaders, but also proportionately more female physician leaders, may find that they really cannot have the same amount of clout as other established specialties within the department of medicine hierarchy.”

Dr. Halasyamani believes that the male hierarchy may be changing. In hospital medicine, she notes, “because the emphasis in inpatient care delivery is so team focused, the leaders in hospital medicine who are able to best meet those goals and have those skills are really the ones who are being given the most opportunity. If the structures within organizations are very hierarchical, then care delivery ends up looking that way. But if the leadership and decision-making structures are more collaborative, then I think care reflects that.”

At her institution, Dr. Halasyamani has had numerous opportunities to help build some of those new structures. For example, in the past year, she helped form an institutional quality and patient safety collaborative practice team, which she chaired jointly with the head of nursing. The team “brings together people who touch the patient; they identify the barriers in delivering the type of care that we want to be proud of every time, and to help solve those problems.”

Possible Pitfalls

Can hospital medicine, in fact, succeed in developing new leadership paradigms? Much will depend on consciously constructing new systems for nurturing talent and leaders. “You really have to think through your mechanisms for recognizing and rewarding achievement and ask if those mechanisms encourage the behaviors you want to encourage, or do they disadvantage people who do the work that you most want done?” says Dr. Ash.

For example, she says, the collaborative nature of hospital medicine can create problems with career advancement. “To do something meaningful, you may need to involve 20 people on a five-year project,” she explains. “How do you ensure that those people don’t get punished for choosing that work?”

Dr. Ash, together with Boston University colleague Phyllis L. Carr, MD, and Linda Pololi, MD, from Brandeis University (the principal investigator) has started a Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation-funded project to “try to change the culture of academic medicine so that it will better encourage and reward collaborative research,” she says. “This change should benefit the entire academic enterprise—although its immediate goal is to make a common career track for women more viable.

“I want to fix a generic problem about the failure to reward certain kinds of highly desirable activities,” says Dr. Ash. “The current reward system hurts women more than men, but I’m not the slightest bit unhappy—it would be a wonderful thing, actually—for men who do collaborative research to also get the career benefits they deserve.”

Advice for Leaders and Women

Are opportunities for women hospitalists improving? Dr. McKean thinks that “hierarchies exist in hospitals, where surgeons are more powerful than physicians in the department of medicine, which has its own internal hierarchy. I see many more women interviewing for internal medicine slots. And, you could say, that’s great, it’s equalizing out. But I wonder if all it’s going to mean is that the pay scale will go down. I think that’s a real consideration. What we’re seeing now is that the starting salary for physician assistants in the hospital may be more than the starting salary for some physicians in primary care. Adding more women [to a specialty] may not change inequalities. The key is adding more women in the highest leadership positions.”

“The whole process of growing talent needs to be done in a take-control sort of way,” says Dr. Ash. There is a predictable, ongoing need to fill leadership positions, she notes, and “not enough good thought about how to systematically reach out to the entire potential talent pool.”

“Mentorship is very important,” emphasizes Dr. McKean. Her own career as a physician was characterized early on, she says, by a lack of support and mentorship. Twenty-five years later, she hopes things are beginning to change and hospital medicine may in fact set the standard for other specialties for both male and female physicians.

“Medicine is always going to be unpredictable,” she continues. “It will always be stressful. There will be acutely ill patients, and people will return [to the hospital] with unanticipated problems. You cannot change this reality. But you can change how things are structured. The more the Society of Hospital Medicine can give people the tools to identify modifiable risk factors in their own practices, help leaders of the hospitalist services analyze what works and what doesn’t work, and allow for as much diversity as possible within each service, I think that a career in hospital medicine will be sustainable and extremely satisfying, and that people will get promoted. They will find different niches in which they are expert.”

To that end, with Win Whitcomb, MD (SHM co-founder), Dr. McKean approached the SHM to charge a task force to identify what makes for a long and satisfying career in hospital medicine and to develop practice standards. The job-person fit is important, and she advises young women hospitalists to take a look at themselves, define what is important, and then “tailor a schedule around that. If it is important to you to be teaching residents, for example, then you need to be in an academic program. If it is more important to have time off, and to work shifts, then you might want to work at a community hospital. There are a lot of different models,” she says “so you have to look at yourself and your husband and the other issues you have to grapple with in addition to your career.”

Above all Dr. McKean urges women (as well as men) to be receptive to advocates or mentors within their organizations.

Going Forward

Overall, Dr. Wachter sees “the nature of the field [of hospital medicine] as one that involves a lot of collaboration and multidisciplinary work seems to draw a certain kind of person. The kind of person who is most happy and successful in our field is one who likes working closely with nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and hospital administrators, and recognizes that the quality of care and patients’ outcomes are going to be, in large part, dependent on how well that team functions.”

Many younger women and men hospitalists are finding that the job-person fit contributes to a fulfilling work/life balance.

“I chose this field because I was interested in inpatient care,” says Dr. Tejedor, and the flexibility offered by her institution has reinforced that choice. “This [hospital medicine] is a great way to have the best of everything.” TH

Writer Gretchen Henkel is based in California.

References

- Women in Medicine Statistics. Prepared by the Women Physicians Congress from Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US, 2005 ed., Chicago. AMA Press. Available at www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/19/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.

- Table 2. Distribution of Residents by Specialty, 1994 Compared to 2004. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine: Statistics and Medical School Benchmarking, 2004-2005. Association of American Medical Colleges; page 12. Available at www.aamc.org/members/wim/statistics/stats05/wimstats2005.pdf. Last accessed January 9, 2005.