User login

With shirt buttons bulging and my panniculus spilling like the top of an oversized muffin over my belt—which was essentially a tourniquet strangling my lower extremities—I examined my options.

After hours of grazing through the snack food pyramid and consuming significant portions of a dinosaur-size turkey, an acromegalic dollop of dressing, a bog of cranberries, and a field of mashed potatoes, I was faced with the proposition of shoveling in another 500 calories cleverly disguised as a heaping slice of pumpkin pie.

The intensity of the situation was palpable. My in-laws sat mouths agape, stunned by the amount and rate at which I forked thousands of calories into my gullet. They fidgeted as I stared with steely, miotic pupils and furrowed, sweat-beaded brow at my prospective ingestion.

The tension heightened as my lower two shirt buttons gave up the cause, careening across the table and striking, respectively, a deserted bowl of creamed corn and the forehead of a comatose relative who had long ago lost interest in watching my acute food intoxication. As my cousins brokered bets over the likelihood of my impending demise, I sat and deliberated, fork hovering over my sugary prey.

Obesity Epidemic

As healthcare practitioners, we are well aware of the dangers of obesity, yet seem paralyzed to make change. However, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to help patients resolve to lose their weight.

A body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more indicates obesity; its slimmer overweight cousin weighs in with a BMI of 25-29.

Overweight or obese people are at increased risk of osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes. Obesity accounts for 300,000 excess deaths per year in the U.S., along with about 10% of all healthcare expenditures, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It affects all ages, races, and professions—including physicians. It is perhaps the most significant health issue facing our nation.

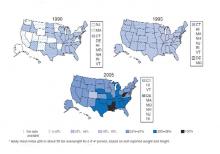

Despite this awareness, we keep getting bigger. In the past 20 years we have seen an epic swelling of American waistlines. In 1990 the CDC reported that among adult residents, 10 states had a prevalence rate of obesity less than 10%, and no states had a rate more than 15% (see Fig. 1, above). By 2006, no state had a prevalence of obesity less than 10%, while only four states clocked in with a rate less than 20%. A whopping 22 states found at least 25% of their inhabitants obese. Since 2005 we’ve become so big the CDC had to create a new category for states with more than 30% of their residents being obese. When the BMI cutoff is dropped to 25 or more, 66% meet of U.S. adults meet this definition for being overweight or obese.

Recent CDC data reveal a glimmer of hope. There was no statistically significant increase in the prevalence of obesity in 2005-2006, compared with 2003-2004. In the earlier time period, 31.1% of men and 33.2% of women were obese, compared with 33.3% of men and 35.3% of women in the most recent time period.

Still, one of every three U.S. adults is obese. That’s 100 million Americans. More than 50% of non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American women age 40-59 are obese. Sixty-one percent of non-Hispanic black women older than 60 are obese.

A complex mix of components, including environment and genetics, determines weight gain. The rapid rate of weight gain in recent years is unlikely to be explained by genetics alone—the population’s genetic composition cannot change that quickly. Thus the bulk of the recent increase in obesity is likely related to cultural and environmental determinants. A 2007 paper by Christakis, et al., found that social networks play a large role in the spread of obesity.1 The study followed 12,067 people for more than 30 years. Those with a friend, sibling, or spouse who became obese over that period were 57%, 40%, and 37% more likely, respectively, to become obese. The authors hypothesize that obesity may become less stigmatized and more tolerable for those surrounded by obese associates. Another theory is that peer groups tend to adopt similar behaviors, such as smoking, eating fast food, and inactivity.

The average person gains about one to two pounds a year.2 When distilled to its simplest form, weight gain occurs anytime calories in exceed calories out—that is, a positive energy balance or gap.

The six weeks from Thanksgiving to New Year’s is an especially vulnerable time for weight gain. In a 2000 study of 195 subjects, the average person gained about one pound during the holiday season. When these subjects were followed up with six months later, there was no statistically significant loss of peri-holiday weight gain. This holiday pound may seem trivial (and keep in mind these subjects gained weight despite being closely watched in a weight-gain study). But this weight appears hard to shed and results in much of the weight gained during adulthood.

However, unlike my Thanksgiving gorging, the hallmark of obesity is the small but frequent positive energy gaps, that is, days of 50 to 100 calories of intake greater than use. Over the course of the year, these small daily caloric gaps are anabolically transformed into pounds.

Resolve to Lose

By now, like me, many of you may have added a holiday pound or two. This may be in addition to a nefarious pound or two added throughout the rest of the year. As you ponder scribing your annual resolutions, consider making weight loss a top priority for your patients and yourself, if appropriate.

Unfortunately no magic bullet will turn your New Year’s resolution into reality, just hard work. The key is to tilt the energy balance toward weight loss by reducing caloric intake and increasing activity. Fortunately this can be done in non-Draconian ways. Just as weight gain can snowball from small daily caloric overdoses, it can be removed the same way. Instead of setting or recommending insurmountable goals to your patients—like reducing intake to 1,000 calories a day or adhering to a triathletic training regimen—the CDC suggests a simpler, more sustainable approach to shedding those pounds, namely tipping your energy balance to a negative 150 calories per day.

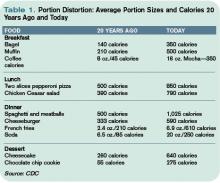

A net negative energy balance of 150 calories per day will at worst stabilize your weight (depending on your current energy balance) and at best net five to 10 pounds of weight loss per year. For most this can result from something as simple as switching your daily Coke to a Diet Coke. Even more ground can be gained by reducing portion size. The super-sizing of the American menu over the past 20 years is one of the prime drivers of the obesity epidemic (see Table 1, p. 64). Consider cutting back in small ways. For example, continue to enjoy that gourmet chocolate chip cookie but downsize it to a smaller version and reduce your intake by 150 to 200 calories.

As important as reducing caloric intake is the need for activity. Adding moderate amounts of exercise five days a week can burn an additional 150 calories per day, reducing overall weight by another five to 10 pounds in a year. This can include things like walking for 30 minutes, swimming for 20 minutes, or biking for 15 minutes. More adventurous (dancing for 30 minutes), parental (pushing a stroller for 30 minutes), agricultural (gardening for 30 minutes), or chore-oriented (shoveling 15 minutes) options also help.

Much to the dismay of my cousin Mike, who bet that I’d eat at least half the piece of Thanksgiving pie, I put down my fork. After packing away a winter’s worth of calories I was feeling diaphoretic and pathetic. I wobbled away from the table and began charting my course to redemption. It would begin the next day with an apple instead of a bagel, an extra hour at the gym—and a trip to the cleaners to get those buttons replaced. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Editor’s note: The author’s driver license claims a weight of 165 pounds. Physical evidence, as well as his wife’s report, paints a substantially different picture.

References

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370-379.

- Yanovksi JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, et al. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:861-867.

With shirt buttons bulging and my panniculus spilling like the top of an oversized muffin over my belt—which was essentially a tourniquet strangling my lower extremities—I examined my options.

After hours of grazing through the snack food pyramid and consuming significant portions of a dinosaur-size turkey, an acromegalic dollop of dressing, a bog of cranberries, and a field of mashed potatoes, I was faced with the proposition of shoveling in another 500 calories cleverly disguised as a heaping slice of pumpkin pie.

The intensity of the situation was palpable. My in-laws sat mouths agape, stunned by the amount and rate at which I forked thousands of calories into my gullet. They fidgeted as I stared with steely, miotic pupils and furrowed, sweat-beaded brow at my prospective ingestion.

The tension heightened as my lower two shirt buttons gave up the cause, careening across the table and striking, respectively, a deserted bowl of creamed corn and the forehead of a comatose relative who had long ago lost interest in watching my acute food intoxication. As my cousins brokered bets over the likelihood of my impending demise, I sat and deliberated, fork hovering over my sugary prey.

Obesity Epidemic

As healthcare practitioners, we are well aware of the dangers of obesity, yet seem paralyzed to make change. However, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to help patients resolve to lose their weight.

A body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more indicates obesity; its slimmer overweight cousin weighs in with a BMI of 25-29.

Overweight or obese people are at increased risk of osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes. Obesity accounts for 300,000 excess deaths per year in the U.S., along with about 10% of all healthcare expenditures, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It affects all ages, races, and professions—including physicians. It is perhaps the most significant health issue facing our nation.

Despite this awareness, we keep getting bigger. In the past 20 years we have seen an epic swelling of American waistlines. In 1990 the CDC reported that among adult residents, 10 states had a prevalence rate of obesity less than 10%, and no states had a rate more than 15% (see Fig. 1, above). By 2006, no state had a prevalence of obesity less than 10%, while only four states clocked in with a rate less than 20%. A whopping 22 states found at least 25% of their inhabitants obese. Since 2005 we’ve become so big the CDC had to create a new category for states with more than 30% of their residents being obese. When the BMI cutoff is dropped to 25 or more, 66% meet of U.S. adults meet this definition for being overweight or obese.

Recent CDC data reveal a glimmer of hope. There was no statistically significant increase in the prevalence of obesity in 2005-2006, compared with 2003-2004. In the earlier time period, 31.1% of men and 33.2% of women were obese, compared with 33.3% of men and 35.3% of women in the most recent time period.

Still, one of every three U.S. adults is obese. That’s 100 million Americans. More than 50% of non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American women age 40-59 are obese. Sixty-one percent of non-Hispanic black women older than 60 are obese.

A complex mix of components, including environment and genetics, determines weight gain. The rapid rate of weight gain in recent years is unlikely to be explained by genetics alone—the population’s genetic composition cannot change that quickly. Thus the bulk of the recent increase in obesity is likely related to cultural and environmental determinants. A 2007 paper by Christakis, et al., found that social networks play a large role in the spread of obesity.1 The study followed 12,067 people for more than 30 years. Those with a friend, sibling, or spouse who became obese over that period were 57%, 40%, and 37% more likely, respectively, to become obese. The authors hypothesize that obesity may become less stigmatized and more tolerable for those surrounded by obese associates. Another theory is that peer groups tend to adopt similar behaviors, such as smoking, eating fast food, and inactivity.

The average person gains about one to two pounds a year.2 When distilled to its simplest form, weight gain occurs anytime calories in exceed calories out—that is, a positive energy balance or gap.

The six weeks from Thanksgiving to New Year’s is an especially vulnerable time for weight gain. In a 2000 study of 195 subjects, the average person gained about one pound during the holiday season. When these subjects were followed up with six months later, there was no statistically significant loss of peri-holiday weight gain. This holiday pound may seem trivial (and keep in mind these subjects gained weight despite being closely watched in a weight-gain study). But this weight appears hard to shed and results in much of the weight gained during adulthood.

However, unlike my Thanksgiving gorging, the hallmark of obesity is the small but frequent positive energy gaps, that is, days of 50 to 100 calories of intake greater than use. Over the course of the year, these small daily caloric gaps are anabolically transformed into pounds.

Resolve to Lose

By now, like me, many of you may have added a holiday pound or two. This may be in addition to a nefarious pound or two added throughout the rest of the year. As you ponder scribing your annual resolutions, consider making weight loss a top priority for your patients and yourself, if appropriate.

Unfortunately no magic bullet will turn your New Year’s resolution into reality, just hard work. The key is to tilt the energy balance toward weight loss by reducing caloric intake and increasing activity. Fortunately this can be done in non-Draconian ways. Just as weight gain can snowball from small daily caloric overdoses, it can be removed the same way. Instead of setting or recommending insurmountable goals to your patients—like reducing intake to 1,000 calories a day or adhering to a triathletic training regimen—the CDC suggests a simpler, more sustainable approach to shedding those pounds, namely tipping your energy balance to a negative 150 calories per day.

A net negative energy balance of 150 calories per day will at worst stabilize your weight (depending on your current energy balance) and at best net five to 10 pounds of weight loss per year. For most this can result from something as simple as switching your daily Coke to a Diet Coke. Even more ground can be gained by reducing portion size. The super-sizing of the American menu over the past 20 years is one of the prime drivers of the obesity epidemic (see Table 1, p. 64). Consider cutting back in small ways. For example, continue to enjoy that gourmet chocolate chip cookie but downsize it to a smaller version and reduce your intake by 150 to 200 calories.

As important as reducing caloric intake is the need for activity. Adding moderate amounts of exercise five days a week can burn an additional 150 calories per day, reducing overall weight by another five to 10 pounds in a year. This can include things like walking for 30 minutes, swimming for 20 minutes, or biking for 15 minutes. More adventurous (dancing for 30 minutes), parental (pushing a stroller for 30 minutes), agricultural (gardening for 30 minutes), or chore-oriented (shoveling 15 minutes) options also help.

Much to the dismay of my cousin Mike, who bet that I’d eat at least half the piece of Thanksgiving pie, I put down my fork. After packing away a winter’s worth of calories I was feeling diaphoretic and pathetic. I wobbled away from the table and began charting my course to redemption. It would begin the next day with an apple instead of a bagel, an extra hour at the gym—and a trip to the cleaners to get those buttons replaced. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Editor’s note: The author’s driver license claims a weight of 165 pounds. Physical evidence, as well as his wife’s report, paints a substantially different picture.

References

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370-379.

- Yanovksi JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, et al. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:861-867.

With shirt buttons bulging and my panniculus spilling like the top of an oversized muffin over my belt—which was essentially a tourniquet strangling my lower extremities—I examined my options.

After hours of grazing through the snack food pyramid and consuming significant portions of a dinosaur-size turkey, an acromegalic dollop of dressing, a bog of cranberries, and a field of mashed potatoes, I was faced with the proposition of shoveling in another 500 calories cleverly disguised as a heaping slice of pumpkin pie.

The intensity of the situation was palpable. My in-laws sat mouths agape, stunned by the amount and rate at which I forked thousands of calories into my gullet. They fidgeted as I stared with steely, miotic pupils and furrowed, sweat-beaded brow at my prospective ingestion.

The tension heightened as my lower two shirt buttons gave up the cause, careening across the table and striking, respectively, a deserted bowl of creamed corn and the forehead of a comatose relative who had long ago lost interest in watching my acute food intoxication. As my cousins brokered bets over the likelihood of my impending demise, I sat and deliberated, fork hovering over my sugary prey.

Obesity Epidemic

As healthcare practitioners, we are well aware of the dangers of obesity, yet seem paralyzed to make change. However, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to help patients resolve to lose their weight.

A body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more indicates obesity; its slimmer overweight cousin weighs in with a BMI of 25-29.

Overweight or obese people are at increased risk of osteoarthritis, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes. Obesity accounts for 300,000 excess deaths per year in the U.S., along with about 10% of all healthcare expenditures, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It affects all ages, races, and professions—including physicians. It is perhaps the most significant health issue facing our nation.

Despite this awareness, we keep getting bigger. In the past 20 years we have seen an epic swelling of American waistlines. In 1990 the CDC reported that among adult residents, 10 states had a prevalence rate of obesity less than 10%, and no states had a rate more than 15% (see Fig. 1, above). By 2006, no state had a prevalence of obesity less than 10%, while only four states clocked in with a rate less than 20%. A whopping 22 states found at least 25% of their inhabitants obese. Since 2005 we’ve become so big the CDC had to create a new category for states with more than 30% of their residents being obese. When the BMI cutoff is dropped to 25 or more, 66% meet of U.S. adults meet this definition for being overweight or obese.

Recent CDC data reveal a glimmer of hope. There was no statistically significant increase in the prevalence of obesity in 2005-2006, compared with 2003-2004. In the earlier time period, 31.1% of men and 33.2% of women were obese, compared with 33.3% of men and 35.3% of women in the most recent time period.

Still, one of every three U.S. adults is obese. That’s 100 million Americans. More than 50% of non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American women age 40-59 are obese. Sixty-one percent of non-Hispanic black women older than 60 are obese.

A complex mix of components, including environment and genetics, determines weight gain. The rapid rate of weight gain in recent years is unlikely to be explained by genetics alone—the population’s genetic composition cannot change that quickly. Thus the bulk of the recent increase in obesity is likely related to cultural and environmental determinants. A 2007 paper by Christakis, et al., found that social networks play a large role in the spread of obesity.1 The study followed 12,067 people for more than 30 years. Those with a friend, sibling, or spouse who became obese over that period were 57%, 40%, and 37% more likely, respectively, to become obese. The authors hypothesize that obesity may become less stigmatized and more tolerable for those surrounded by obese associates. Another theory is that peer groups tend to adopt similar behaviors, such as smoking, eating fast food, and inactivity.

The average person gains about one to two pounds a year.2 When distilled to its simplest form, weight gain occurs anytime calories in exceed calories out—that is, a positive energy balance or gap.

The six weeks from Thanksgiving to New Year’s is an especially vulnerable time for weight gain. In a 2000 study of 195 subjects, the average person gained about one pound during the holiday season. When these subjects were followed up with six months later, there was no statistically significant loss of peri-holiday weight gain. This holiday pound may seem trivial (and keep in mind these subjects gained weight despite being closely watched in a weight-gain study). But this weight appears hard to shed and results in much of the weight gained during adulthood.

However, unlike my Thanksgiving gorging, the hallmark of obesity is the small but frequent positive energy gaps, that is, days of 50 to 100 calories of intake greater than use. Over the course of the year, these small daily caloric gaps are anabolically transformed into pounds.

Resolve to Lose

By now, like me, many of you may have added a holiday pound or two. This may be in addition to a nefarious pound or two added throughout the rest of the year. As you ponder scribing your annual resolutions, consider making weight loss a top priority for your patients and yourself, if appropriate.

Unfortunately no magic bullet will turn your New Year’s resolution into reality, just hard work. The key is to tilt the energy balance toward weight loss by reducing caloric intake and increasing activity. Fortunately this can be done in non-Draconian ways. Just as weight gain can snowball from small daily caloric overdoses, it can be removed the same way. Instead of setting or recommending insurmountable goals to your patients—like reducing intake to 1,000 calories a day or adhering to a triathletic training regimen—the CDC suggests a simpler, more sustainable approach to shedding those pounds, namely tipping your energy balance to a negative 150 calories per day.

A net negative energy balance of 150 calories per day will at worst stabilize your weight (depending on your current energy balance) and at best net five to 10 pounds of weight loss per year. For most this can result from something as simple as switching your daily Coke to a Diet Coke. Even more ground can be gained by reducing portion size. The super-sizing of the American menu over the past 20 years is one of the prime drivers of the obesity epidemic (see Table 1, p. 64). Consider cutting back in small ways. For example, continue to enjoy that gourmet chocolate chip cookie but downsize it to a smaller version and reduce your intake by 150 to 200 calories.

As important as reducing caloric intake is the need for activity. Adding moderate amounts of exercise five days a week can burn an additional 150 calories per day, reducing overall weight by another five to 10 pounds in a year. This can include things like walking for 30 minutes, swimming for 20 minutes, or biking for 15 minutes. More adventurous (dancing for 30 minutes), parental (pushing a stroller for 30 minutes), agricultural (gardening for 30 minutes), or chore-oriented (shoveling 15 minutes) options also help.

Much to the dismay of my cousin Mike, who bet that I’d eat at least half the piece of Thanksgiving pie, I put down my fork. After packing away a winter’s worth of calories I was feeling diaphoretic and pathetic. I wobbled away from the table and began charting my course to redemption. It would begin the next day with an apple instead of a bagel, an extra hour at the gym—and a trip to the cleaners to get those buttons replaced. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Editor’s note: The author’s driver license claims a weight of 165 pounds. Physical evidence, as well as his wife’s report, paints a substantially different picture.

References

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:370-379.

- Yanovksi JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, et al. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:861-867.