User login

Ms. B, age 31, experienced her first depressive episode at age 24 during her second year of law school. These episodes are characterized by insomnia, sadness, guilt, suicidal ideation, and impaired concentration that affect her ability to function at work and interfere with her ability to maintain relationships. She has no history of mania, hypomania, or psychosis.

Ms. B has approximately 2 severe episodes a year, lasting 8 to 10 weeks. She has failed adequate (≥6 week) trials of sertraline, 200 mg/d; venlafaxine XR, 300 mg/d; bupropion XL, 450 mg/d; and vortioxetine, 20 mg/d. Adjunctive treatments were not well tolerated; lithium caused severe nausea and aripiprazole lead to intolerable akathisia. Psychotherapy was ineffective. A trial of electroconvulsive therapy relieved her depression but resulted in significant memory impairment.

Is ketamine a treatment option for Ms. B?

Ketamine, an N-methyl-D aspartate antagonist, was approved by the FDA in 1970.

as a dissociative anesthetic. It proved useful in military battlefield situations. The drug then became popular as a “club drug” and is used recreationally as a dissociative agent. It recently has been used clinically for treating post-operative pain and treatment-resistant depression (TRD). It has shown efficacy for several specific symptom clusters in depression, including anhedonia and suicidality.

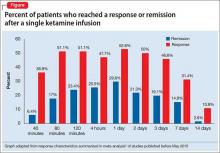

Several small randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine—some of which studied TRD—have reported antidepressant effects after a single IV dose of 0.5 mg/kg in depressed patients.1,2 The response rate, defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms, is reported to be as high as 50% to 71% twenty-four hours after infusion, with significant improvements noted in some patients after just 40 minutes.1 These effects, peaking at 24 hours, last ≥72 hours in approximately 50% of patients, but gradually return to baseline over 1 to 2 weeks (Figure1). The most common post-infusion adverse effects include:

- dissociation

- dizziness

- blurred vision

- poor concentration

- nausea.

Transient sedation and psychotomimetic symptoms, such as hallucinations, abnormal sensations, and confusion, also have been noted, as well as a small but significant increase in blood pressure shortly after infusion.1

Use of repeated doses of ketamine also has been studied, although larger and extended-duration studies are lacking. Two groups3,4 examined thrice weekly infusions (N = 24) and 1 group5 studied twice weekly infusions of 0.5 mg/kg for 2 weeks (6 and 4 doses, respectively) (N = 10). With thrice weekly dosing, 79% to 90% of patients showed symptomatic response overall and 25% to 100% of patients saw improvement after the first dose.3,4 Of the 20 patients who responded, 65% were still reporting improved symptoms 2 weeks after the last infusion and 40% showed response for >28 days.3,4 With twice weekly dosing,5 the response rate was 80% in 10 patients, while 5 patients (50%) achieved remission, lasting at least 28 days in 2 patients.

The authors of a recent Cochrane review6 evaluated ketamine for treating depression and concluded that, although there is evidence for ketamine’s efficacy early in treatment, effects are less certain after 2 weeks post-treatment. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health also conducted an appraisal7 of ketamine for treating a variety of mental illnesses and similarly noted that, despite evidence in acute studies, (1) the role of the drug in clinical practice is unclear and (2) further comparative studies, as well as longer-term studies, are needed.

Last, the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments1 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, whose authors concluded that ketamine produces a rapid and robust antidepressant effect that appears to be transient. They warn that, although results are promising, “enthusiasm should be tempered” and suggest that “its use in the clinical setting warrants caution.”

Should you consider treating depression with ketamine?

Although evidence for using ketamine as a rapid treatment of TRD is promising and non-IV forms of ketamine are being researched (eg, intranasal esketamine), there are factors that limit clinical application:

- The short duration of effect noted in studies highlights the need for research on maintenance strategies to assess longer-term efficacy as well as safety. For example, long-term ketamine abuse has been associated with cases of ulcerative or hemorrhagic cystitis causing severe and persistent pain, requiring a partial cystectomy.8,9 Further, long-term ketamine use for pain has been associated with a transaminitis. Lastly, ketamine self-treatment for depression with escalating doses has also been associated with severe ketamine addiction and sequelae.10 The incidence and severity of these adverse effects at dosages and administration frequencies that might be required for maintenance treatment of depression is unclear and requires further investigation.

- Psychotomimetic and cardiovascular adverse effects of ketamine warrant monitoring in an acute clinical setting, until longer term safety and monitoring protocols are developed. Of note, the dosing regimen used in most studies requires anesthesia monitoring in many health care systems. Although acute adverse effects in studies to date are infrequent, both cardiovascular and gastrointestinal (vomiting) events requiring IV intervention have been reported,4 underscoring the importance of anesthesiologist involvement.

- Tolerance. It is unknown if patients develop tolerance to ketamine with recurring dosages and may present additional safety concerns with repeated, higher dosages. Lastly, patients on extended ketamine therapy could encounter drug interactions with agents commonly used to treat depression.

Although some authors1,6 advise caution with widespread ketamine use, patients with TRD want effective treatments and may discount these warnings. Even though longer-term studies are needed, ketamine “infusion clinics” are already being established. Before referring patients to such clinics, it is important to understand the current clinical and safety limitations and requirements for ketamine in TRD and to consider and discuss the risks and benefits carefully.

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. B has tried several antidepressants and adjunctive therapies without success, and her depression is severe enough to affect her functioning in several domains, it might be reasonable to discuss a trial of ketamine. However, Ms. B also should be presented non-ketamine alternatives, such as other adjunctive strategies (liothyronine, buspirone, cognitive-behavioral therapy) or a trial of nortriptyline or a monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

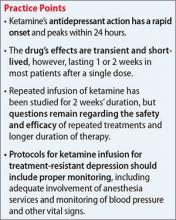

If ketamine is thought to be the best option for Ms. B, her provider needs to establish a clear expectation that the effects likely will be temporary. Monitoring should include applying a rating scale to assess depressive symptoms, suicidality, and psychotomimetic symptoms. During and shortly after infusion, anesthesia support should be provided and blood pressure and other vital signs should be monitored. Additional monitoring, such as telemetry, might be indicated.

1. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, et al; APA Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):950-966.

2. Murrough JW, losifescu DV, Chang LC, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1134-1142.

3. aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):139-145.

4. Shiroma PR, Johns B, Kuskowski M, et al. Augmentation of response and remission to serial intravenous subanesthetic ketamine in treatment resistant depression. J Affect Disorder. 2014;155:123-129.

5. Ramussen KG, Lineberry TW, Galardy CW, et al. Serial infusions of low-dose ketamine for major depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(5):444-450.

6. Caddy C, Amit BH, McCloud TL, et al. Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub2.

7. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Intravenous ketamine for the treatment of mental health disorders: a review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014. https://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/htis/dec-2014/RC0572%20IV%20Ketamine%20Report%20final.pdf. Published August 20, 2014. Accessed April 13, 2016.

8. Jhang JF, Birder LA, Chancellor MB, et al. Patient characteristics for different therapeutic strategies in the management ketamine cystitis [published online March 21, 2016]. Neurourol Urodyn. doi: 10.1002/nau.22996.

9. Busse J, Phillips L, Schechter W. Long-term intravenous ketamine for analgesia in a child with severe chronic intestinal graft versus host disease. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2015;2015:834168. doi:10.1155/2015/834168.

10. Bonnet U. Long-term ketamine self-injections in major depressive disorder: focus on tolerance in ketamine’s antidepressant response and the development of ketamine addiction. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(4):276-285.

Ms. B, age 31, experienced her first depressive episode at age 24 during her second year of law school. These episodes are characterized by insomnia, sadness, guilt, suicidal ideation, and impaired concentration that affect her ability to function at work and interfere with her ability to maintain relationships. She has no history of mania, hypomania, or psychosis.

Ms. B has approximately 2 severe episodes a year, lasting 8 to 10 weeks. She has failed adequate (≥6 week) trials of sertraline, 200 mg/d; venlafaxine XR, 300 mg/d; bupropion XL, 450 mg/d; and vortioxetine, 20 mg/d. Adjunctive treatments were not well tolerated; lithium caused severe nausea and aripiprazole lead to intolerable akathisia. Psychotherapy was ineffective. A trial of electroconvulsive therapy relieved her depression but resulted in significant memory impairment.

Is ketamine a treatment option for Ms. B?

Ketamine, an N-methyl-D aspartate antagonist, was approved by the FDA in 1970.

as a dissociative anesthetic. It proved useful in military battlefield situations. The drug then became popular as a “club drug” and is used recreationally as a dissociative agent. It recently has been used clinically for treating post-operative pain and treatment-resistant depression (TRD). It has shown efficacy for several specific symptom clusters in depression, including anhedonia and suicidality.

Several small randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine—some of which studied TRD—have reported antidepressant effects after a single IV dose of 0.5 mg/kg in depressed patients.1,2 The response rate, defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms, is reported to be as high as 50% to 71% twenty-four hours after infusion, with significant improvements noted in some patients after just 40 minutes.1 These effects, peaking at 24 hours, last ≥72 hours in approximately 50% of patients, but gradually return to baseline over 1 to 2 weeks (Figure1). The most common post-infusion adverse effects include:

- dissociation

- dizziness

- blurred vision

- poor concentration

- nausea.

Transient sedation and psychotomimetic symptoms, such as hallucinations, abnormal sensations, and confusion, also have been noted, as well as a small but significant increase in blood pressure shortly after infusion.1

Use of repeated doses of ketamine also has been studied, although larger and extended-duration studies are lacking. Two groups3,4 examined thrice weekly infusions (N = 24) and 1 group5 studied twice weekly infusions of 0.5 mg/kg for 2 weeks (6 and 4 doses, respectively) (N = 10). With thrice weekly dosing, 79% to 90% of patients showed symptomatic response overall and 25% to 100% of patients saw improvement after the first dose.3,4 Of the 20 patients who responded, 65% were still reporting improved symptoms 2 weeks after the last infusion and 40% showed response for >28 days.3,4 With twice weekly dosing,5 the response rate was 80% in 10 patients, while 5 patients (50%) achieved remission, lasting at least 28 days in 2 patients.

The authors of a recent Cochrane review6 evaluated ketamine for treating depression and concluded that, although there is evidence for ketamine’s efficacy early in treatment, effects are less certain after 2 weeks post-treatment. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health also conducted an appraisal7 of ketamine for treating a variety of mental illnesses and similarly noted that, despite evidence in acute studies, (1) the role of the drug in clinical practice is unclear and (2) further comparative studies, as well as longer-term studies, are needed.

Last, the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments1 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, whose authors concluded that ketamine produces a rapid and robust antidepressant effect that appears to be transient. They warn that, although results are promising, “enthusiasm should be tempered” and suggest that “its use in the clinical setting warrants caution.”

Should you consider treating depression with ketamine?

Although evidence for using ketamine as a rapid treatment of TRD is promising and non-IV forms of ketamine are being researched (eg, intranasal esketamine), there are factors that limit clinical application:

- The short duration of effect noted in studies highlights the need for research on maintenance strategies to assess longer-term efficacy as well as safety. For example, long-term ketamine abuse has been associated with cases of ulcerative or hemorrhagic cystitis causing severe and persistent pain, requiring a partial cystectomy.8,9 Further, long-term ketamine use for pain has been associated with a transaminitis. Lastly, ketamine self-treatment for depression with escalating doses has also been associated with severe ketamine addiction and sequelae.10 The incidence and severity of these adverse effects at dosages and administration frequencies that might be required for maintenance treatment of depression is unclear and requires further investigation.

- Psychotomimetic and cardiovascular adverse effects of ketamine warrant monitoring in an acute clinical setting, until longer term safety and monitoring protocols are developed. Of note, the dosing regimen used in most studies requires anesthesia monitoring in many health care systems. Although acute adverse effects in studies to date are infrequent, both cardiovascular and gastrointestinal (vomiting) events requiring IV intervention have been reported,4 underscoring the importance of anesthesiologist involvement.

- Tolerance. It is unknown if patients develop tolerance to ketamine with recurring dosages and may present additional safety concerns with repeated, higher dosages. Lastly, patients on extended ketamine therapy could encounter drug interactions with agents commonly used to treat depression.

Although some authors1,6 advise caution with widespread ketamine use, patients with TRD want effective treatments and may discount these warnings. Even though longer-term studies are needed, ketamine “infusion clinics” are already being established. Before referring patients to such clinics, it is important to understand the current clinical and safety limitations and requirements for ketamine in TRD and to consider and discuss the risks and benefits carefully.

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. B has tried several antidepressants and adjunctive therapies without success, and her depression is severe enough to affect her functioning in several domains, it might be reasonable to discuss a trial of ketamine. However, Ms. B also should be presented non-ketamine alternatives, such as other adjunctive strategies (liothyronine, buspirone, cognitive-behavioral therapy) or a trial of nortriptyline or a monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

If ketamine is thought to be the best option for Ms. B, her provider needs to establish a clear expectation that the effects likely will be temporary. Monitoring should include applying a rating scale to assess depressive symptoms, suicidality, and psychotomimetic symptoms. During and shortly after infusion, anesthesia support should be provided and blood pressure and other vital signs should be monitored. Additional monitoring, such as telemetry, might be indicated.

Ms. B, age 31, experienced her first depressive episode at age 24 during her second year of law school. These episodes are characterized by insomnia, sadness, guilt, suicidal ideation, and impaired concentration that affect her ability to function at work and interfere with her ability to maintain relationships. She has no history of mania, hypomania, or psychosis.

Ms. B has approximately 2 severe episodes a year, lasting 8 to 10 weeks. She has failed adequate (≥6 week) trials of sertraline, 200 mg/d; venlafaxine XR, 300 mg/d; bupropion XL, 450 mg/d; and vortioxetine, 20 mg/d. Adjunctive treatments were not well tolerated; lithium caused severe nausea and aripiprazole lead to intolerable akathisia. Psychotherapy was ineffective. A trial of electroconvulsive therapy relieved her depression but resulted in significant memory impairment.

Is ketamine a treatment option for Ms. B?

Ketamine, an N-methyl-D aspartate antagonist, was approved by the FDA in 1970.

as a dissociative anesthetic. It proved useful in military battlefield situations. The drug then became popular as a “club drug” and is used recreationally as a dissociative agent. It recently has been used clinically for treating post-operative pain and treatment-resistant depression (TRD). It has shown efficacy for several specific symptom clusters in depression, including anhedonia and suicidality.

Several small randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine—some of which studied TRD—have reported antidepressant effects after a single IV dose of 0.5 mg/kg in depressed patients.1,2 The response rate, defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms, is reported to be as high as 50% to 71% twenty-four hours after infusion, with significant improvements noted in some patients after just 40 minutes.1 These effects, peaking at 24 hours, last ≥72 hours in approximately 50% of patients, but gradually return to baseline over 1 to 2 weeks (Figure1). The most common post-infusion adverse effects include:

- dissociation

- dizziness

- blurred vision

- poor concentration

- nausea.

Transient sedation and psychotomimetic symptoms, such as hallucinations, abnormal sensations, and confusion, also have been noted, as well as a small but significant increase in blood pressure shortly after infusion.1

Use of repeated doses of ketamine also has been studied, although larger and extended-duration studies are lacking. Two groups3,4 examined thrice weekly infusions (N = 24) and 1 group5 studied twice weekly infusions of 0.5 mg/kg for 2 weeks (6 and 4 doses, respectively) (N = 10). With thrice weekly dosing, 79% to 90% of patients showed symptomatic response overall and 25% to 100% of patients saw improvement after the first dose.3,4 Of the 20 patients who responded, 65% were still reporting improved symptoms 2 weeks after the last infusion and 40% showed response for >28 days.3,4 With twice weekly dosing,5 the response rate was 80% in 10 patients, while 5 patients (50%) achieved remission, lasting at least 28 days in 2 patients.

The authors of a recent Cochrane review6 evaluated ketamine for treating depression and concluded that, although there is evidence for ketamine’s efficacy early in treatment, effects are less certain after 2 weeks post-treatment. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health also conducted an appraisal7 of ketamine for treating a variety of mental illnesses and similarly noted that, despite evidence in acute studies, (1) the role of the drug in clinical practice is unclear and (2) further comparative studies, as well as longer-term studies, are needed.

Last, the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments1 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, whose authors concluded that ketamine produces a rapid and robust antidepressant effect that appears to be transient. They warn that, although results are promising, “enthusiasm should be tempered” and suggest that “its use in the clinical setting warrants caution.”

Should you consider treating depression with ketamine?

Although evidence for using ketamine as a rapid treatment of TRD is promising and non-IV forms of ketamine are being researched (eg, intranasal esketamine), there are factors that limit clinical application:

- The short duration of effect noted in studies highlights the need for research on maintenance strategies to assess longer-term efficacy as well as safety. For example, long-term ketamine abuse has been associated with cases of ulcerative or hemorrhagic cystitis causing severe and persistent pain, requiring a partial cystectomy.8,9 Further, long-term ketamine use for pain has been associated with a transaminitis. Lastly, ketamine self-treatment for depression with escalating doses has also been associated with severe ketamine addiction and sequelae.10 The incidence and severity of these adverse effects at dosages and administration frequencies that might be required for maintenance treatment of depression is unclear and requires further investigation.

- Psychotomimetic and cardiovascular adverse effects of ketamine warrant monitoring in an acute clinical setting, until longer term safety and monitoring protocols are developed. Of note, the dosing regimen used in most studies requires anesthesia monitoring in many health care systems. Although acute adverse effects in studies to date are infrequent, both cardiovascular and gastrointestinal (vomiting) events requiring IV intervention have been reported,4 underscoring the importance of anesthesiologist involvement.

- Tolerance. It is unknown if patients develop tolerance to ketamine with recurring dosages and may present additional safety concerns with repeated, higher dosages. Lastly, patients on extended ketamine therapy could encounter drug interactions with agents commonly used to treat depression.

Although some authors1,6 advise caution with widespread ketamine use, patients with TRD want effective treatments and may discount these warnings. Even though longer-term studies are needed, ketamine “infusion clinics” are already being established. Before referring patients to such clinics, it is important to understand the current clinical and safety limitations and requirements for ketamine in TRD and to consider and discuss the risks and benefits carefully.

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. B has tried several antidepressants and adjunctive therapies without success, and her depression is severe enough to affect her functioning in several domains, it might be reasonable to discuss a trial of ketamine. However, Ms. B also should be presented non-ketamine alternatives, such as other adjunctive strategies (liothyronine, buspirone, cognitive-behavioral therapy) or a trial of nortriptyline or a monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

If ketamine is thought to be the best option for Ms. B, her provider needs to establish a clear expectation that the effects likely will be temporary. Monitoring should include applying a rating scale to assess depressive symptoms, suicidality, and psychotomimetic symptoms. During and shortly after infusion, anesthesia support should be provided and blood pressure and other vital signs should be monitored. Additional monitoring, such as telemetry, might be indicated.

1. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, et al; APA Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):950-966.

2. Murrough JW, losifescu DV, Chang LC, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1134-1142.

3. aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):139-145.

4. Shiroma PR, Johns B, Kuskowski M, et al. Augmentation of response and remission to serial intravenous subanesthetic ketamine in treatment resistant depression. J Affect Disorder. 2014;155:123-129.

5. Ramussen KG, Lineberry TW, Galardy CW, et al. Serial infusions of low-dose ketamine for major depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(5):444-450.

6. Caddy C, Amit BH, McCloud TL, et al. Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub2.

7. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Intravenous ketamine for the treatment of mental health disorders: a review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014. https://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/htis/dec-2014/RC0572%20IV%20Ketamine%20Report%20final.pdf. Published August 20, 2014. Accessed April 13, 2016.

8. Jhang JF, Birder LA, Chancellor MB, et al. Patient characteristics for different therapeutic strategies in the management ketamine cystitis [published online March 21, 2016]. Neurourol Urodyn. doi: 10.1002/nau.22996.

9. Busse J, Phillips L, Schechter W. Long-term intravenous ketamine for analgesia in a child with severe chronic intestinal graft versus host disease. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2015;2015:834168. doi:10.1155/2015/834168.

10. Bonnet U. Long-term ketamine self-injections in major depressive disorder: focus on tolerance in ketamine’s antidepressant response and the development of ketamine addiction. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(4):276-285.

1. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, et al; APA Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):950-966.

2. Murrough JW, losifescu DV, Chang LC, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1134-1142.

3. aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):139-145.

4. Shiroma PR, Johns B, Kuskowski M, et al. Augmentation of response and remission to serial intravenous subanesthetic ketamine in treatment resistant depression. J Affect Disorder. 2014;155:123-129.

5. Ramussen KG, Lineberry TW, Galardy CW, et al. Serial infusions of low-dose ketamine for major depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(5):444-450.

6. Caddy C, Amit BH, McCloud TL, et al. Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub2.

7. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Intravenous ketamine for the treatment of mental health disorders: a review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014. https://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/htis/dec-2014/RC0572%20IV%20Ketamine%20Report%20final.pdf. Published August 20, 2014. Accessed April 13, 2016.

8. Jhang JF, Birder LA, Chancellor MB, et al. Patient characteristics for different therapeutic strategies in the management ketamine cystitis [published online March 21, 2016]. Neurourol Urodyn. doi: 10.1002/nau.22996.

9. Busse J, Phillips L, Schechter W. Long-term intravenous ketamine for analgesia in a child with severe chronic intestinal graft versus host disease. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2015;2015:834168. doi:10.1155/2015/834168.

10. Bonnet U. Long-term ketamine self-injections in major depressive disorder: focus on tolerance in ketamine’s antidepressant response and the development of ketamine addiction. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(4):276-285.