User login

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

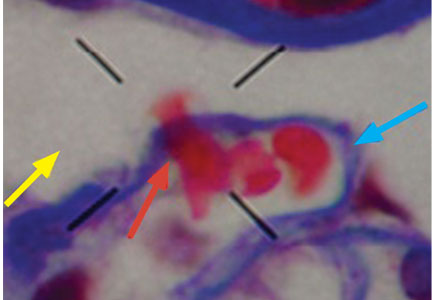

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

A 23-year-old woman presented with hematuria. Her blood pressure was normal, and she had no rash, joint pain, or other symptoms. Urinalysis was positive for proteinuria and hematuria, and urinary sediment analysis showed dysmorphic red blood cells (RBCs) and red cell casts, leading to a diagnosis of glomerulonephritis. She had proteinuria of 1.2 g/24 hours. Laboratory tests for systemic diseases were negative. Renal biopsy study revealed stage III immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.

GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Glomerular hematuria may represent an immune-mediated injury to the glomerular capillary wall, but it can also be present in noninflammatory glomerulopathies.1

The type of dysmorphic RBCs (crenated or misshapen cells, acanthocytes) may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic red cells alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding, while acanthocytes (ring-shaped RBCs with vesicle-shaped protrusions best seen on phase-contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease.2 For example, in 1 study,3 the presence of acanthocytes comprising at least 5% of excreted RBCs had a sensitivity of 52% for glomerular disease and a specificity of 98%.3

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.

- Collar JE, Ladva S, Cairns TD, Cattell V. Red cell traverse through thin glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int 2001; 59:2069–2072.

- Fogazzi GB, Ponticelli C, Ritz E. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:30.

- Köhler H, Wandel E, Brunck B. Acanthocyturia—a characteristic marker for glomerular bleeding. Kidney Int 1991; 40:115–120.

- Fogazzi GB. The Urinary Sediment: An Integrated View. 3rd ed. France: Elsevier; 2010.

- Briner VA, Reinhart WH. In vitro production of ‘glomerular red cells’: role of pH and osmolality. Nephron 1990; 56:13–18.

- Schramek P, Moritsch A, Haschkowitz H, Binder BR, Maier M. In vitro generation of dysmorphic erythrocytes. Kidney Int 1989; 36:72–77.

- Pollock C, Liu PL, Györy AZ, et al. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells—value in diagnosis. Kidney Int 1989; 36:1045–1049.

- Shichiri M, Hosoda K, Nishio Y, et al. Red-cell-volume distribution curves in diagnosis of glomerular and non-glomerular haematuria. Lancet 1988; 1:908–911.