User login

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12

Some data suggest that patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients have no effect on patient perceptions or their satisfaction with care.13 However, we felt that collaboration among a multidisciplinary team would help us achieve better outcomes. For example, our patients would perceive the care team (MD-RN) as a cohesive unit, and in turn gain trust in the members of the treatment team, as found by Nathalie McIntosh, PhD, et al and by Jason Ramirez, MD.7,16 Our vision was to empower nurses to be advocates for patients and their family members as they navigated their acute care admission. Nurses could also support physicians by communicating the physicians’ care plans to families and patients. After rounding with the physician, the nurse would be part of the decision-making process and care planning.17

Every rounding session had discharge planning and hospital stay expectations that were shared with the patient and nurse, who could then partner with case managers and social workers, which would streamline and reduce length of stay.14 We hoped rounding would also decrease the number of nurse pages to clarify or question orders. This would, in turn, improve daily work flow for the physicians and the nursing team with improvements in employee satisfaction scores.15 A study also has demonstrated a reduction in readmission rates from nurse-physician rounding.19

A disconnect in communication and trust between physicians and the nursing staff was reflected in low patient experience scores and perceived quality of care received during in-hospital stay. Gwendolyn Lancaster, EdD, MSN, RN, CCRN, et al, as well as a Joint Commission report, demonstrated how a lack of communication and poor team dynamics can translate to poor patient experience and be a major cause for sentinel events.6,20 Artificial, forced hierarchies and role perception among health care team members led to frustration, hostility, and distrust, which compromises quality and patient safety.1

One of our biggest challenges when we started this project was explaining the “Why” to the hospitalist group and nursing staff. Physicians were used to being the dominant partner in the team. Partnering with and engaging nurses in shared decision making and care planning was a seismic shift in culture and work flow within the care team. Early gains helped skeptical team members begin to understand the value in nurse-physician rounding. Near universal adoption of the rounding process at Lee Health has caused improvements in the working relationship and trust among the health care professionals. We have seen improvements in utilization management, as well as appropriateness and timeliness of resource use, because of better communication and understanding of care plans by nursing and physicians. Collaboration with specialists and alignment in care planning are other gains. Hospitalists and nurses are both very satisfied with the decrease in the number of pages during the day, and this has lowered stressors on health care teams.

How we did it

Nurse-physician rounding is a proven method to improve collaboration, communication, and relationships among health care team members in acute care facilities. In the complex health care challenges faced today, this improved work flow for taking care of patients can help advance the Quadruple Aim of high quality, low cost, improved patient experience, physician, and staff satisfaction.21

Lee Health System includes four facilities in Lee County, with a total of 1,216 licensed adult acute care beds. The pilot project was started in 2014.

Initially the vice president of nursing and the hospitalist medical director met to create an education plan for nurses and physicians. We chose one adult medicine unit to pilot the project because there already existed a closely knit nursing and hospitalist team. In our facility there is no strict geographical rounding; each hospitalist carries between three and six patients in the unit. As a first step, a nurse floor assignment sheet was faxed in the morning to the hospitalist office with the direct phone numbers of the nurses. The unit clerk, using physician assignments in the EHR, teamed up the physician and nurses for rounding. Once the physician arrived at the unit, he or she checked in with the unit clerk, who alerted nurses that the hospitalist was available on the floor to commence rounding. If the primary nurse was unavailable because of other duties or breaks, the charge nurse rounded with the physician.

Once in the room with the patient, the duo introduced themselves as members of the treatment team and acknowledged the patient’s needs. During the visit, care plans and treatment were reviewed, the patient’s questions were answered, a physical exam was completed, and lab and imaging results were discussed; the nurse also helped raise questions he or she had received from family members so answers could be communicated to the family later. Patients appreciated knowing that their physicians and nurses were working together as a team for their safety and recovery. During the visit, care was taken to focus specially on the course of hospitalization and discharge planning.

We tracked the rounding with a manual paper process maintained by the charge nurse. Our initial rounding rates were 30%-40%, and we continued to promote this initiative to the team, and eventually the importance and value of these rounds caught on with both nurses and physicians, and now our current average rounding rate is 90%. We then decided to scale this to all units in the hospital.

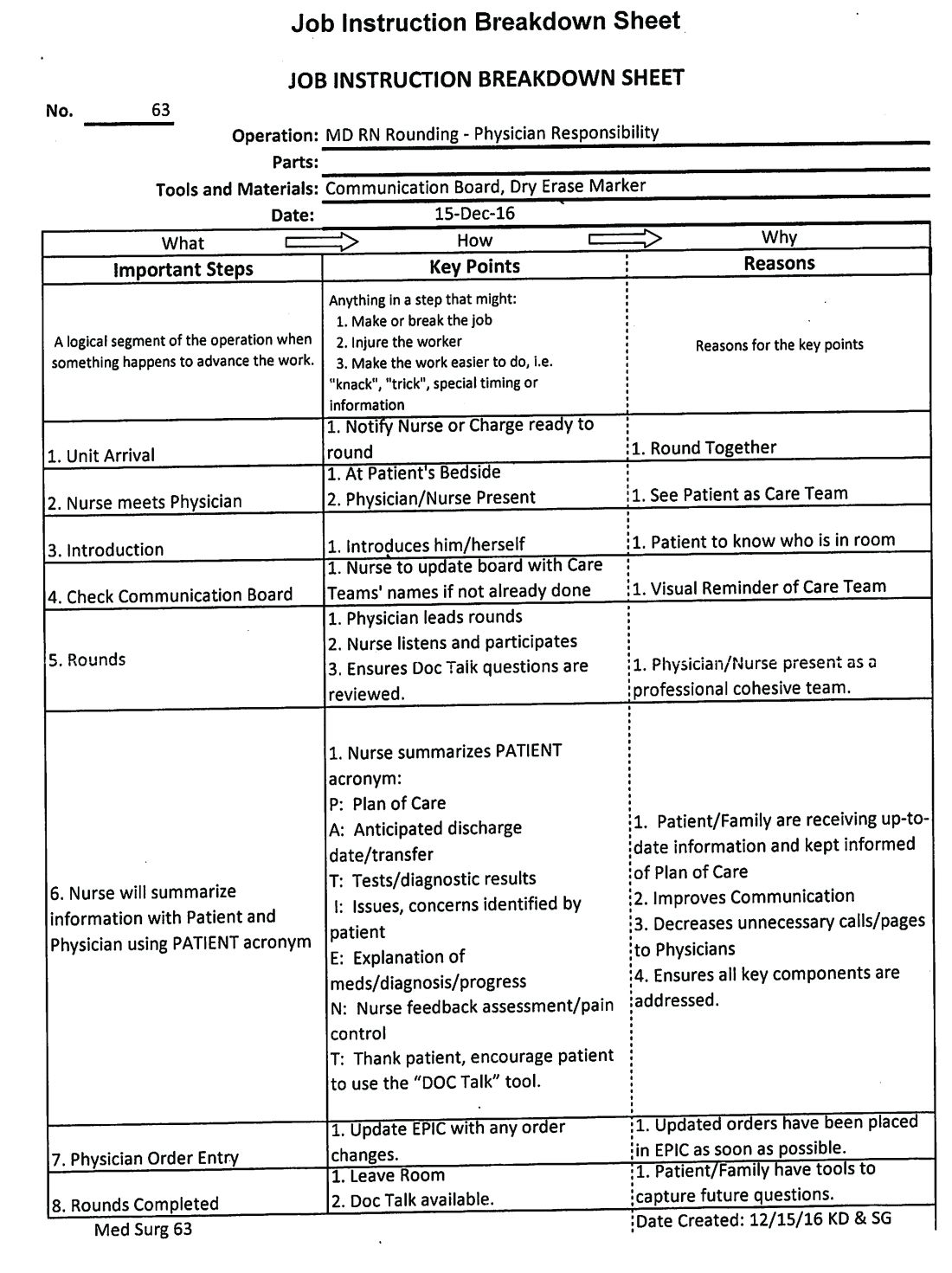

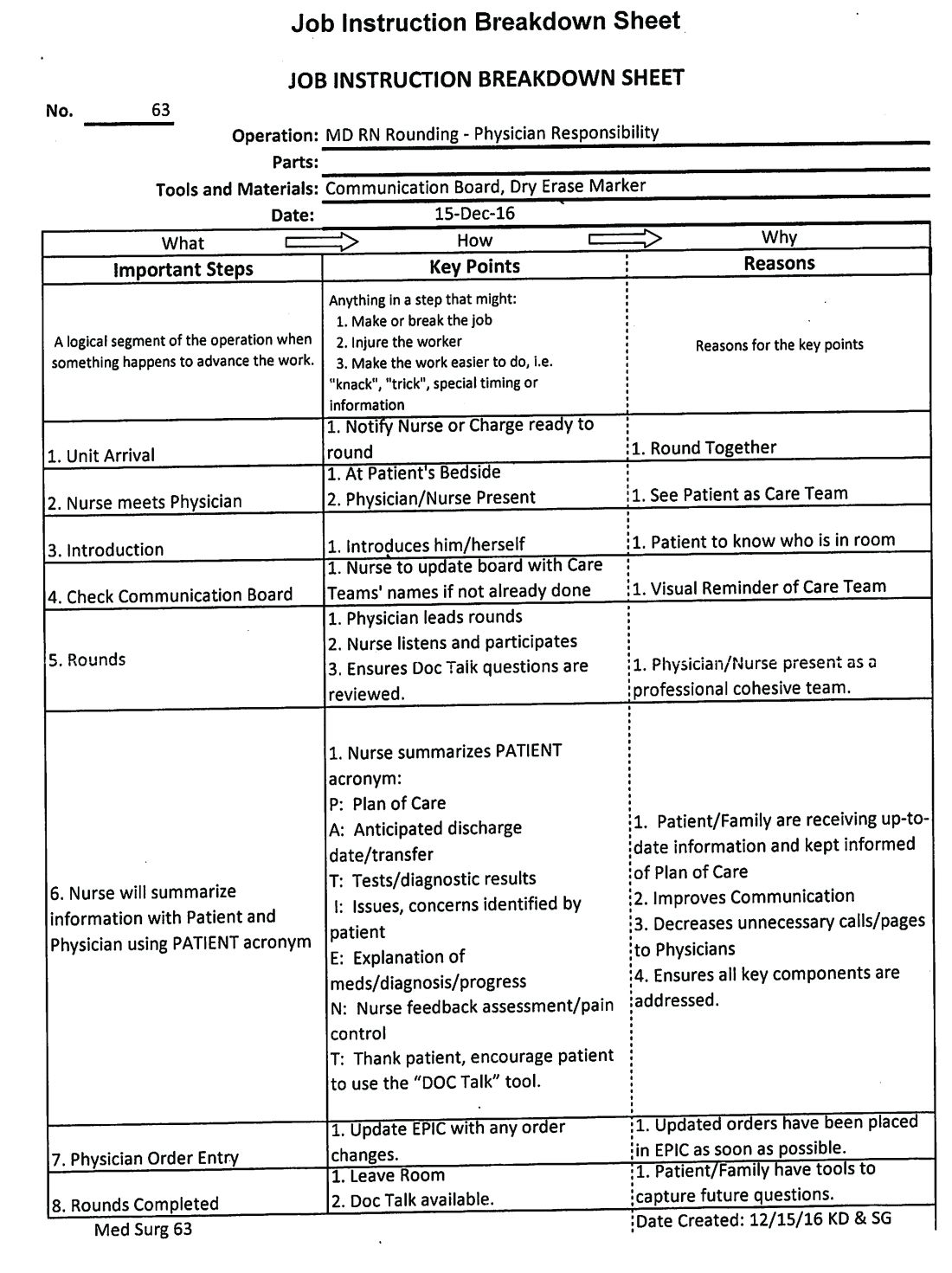

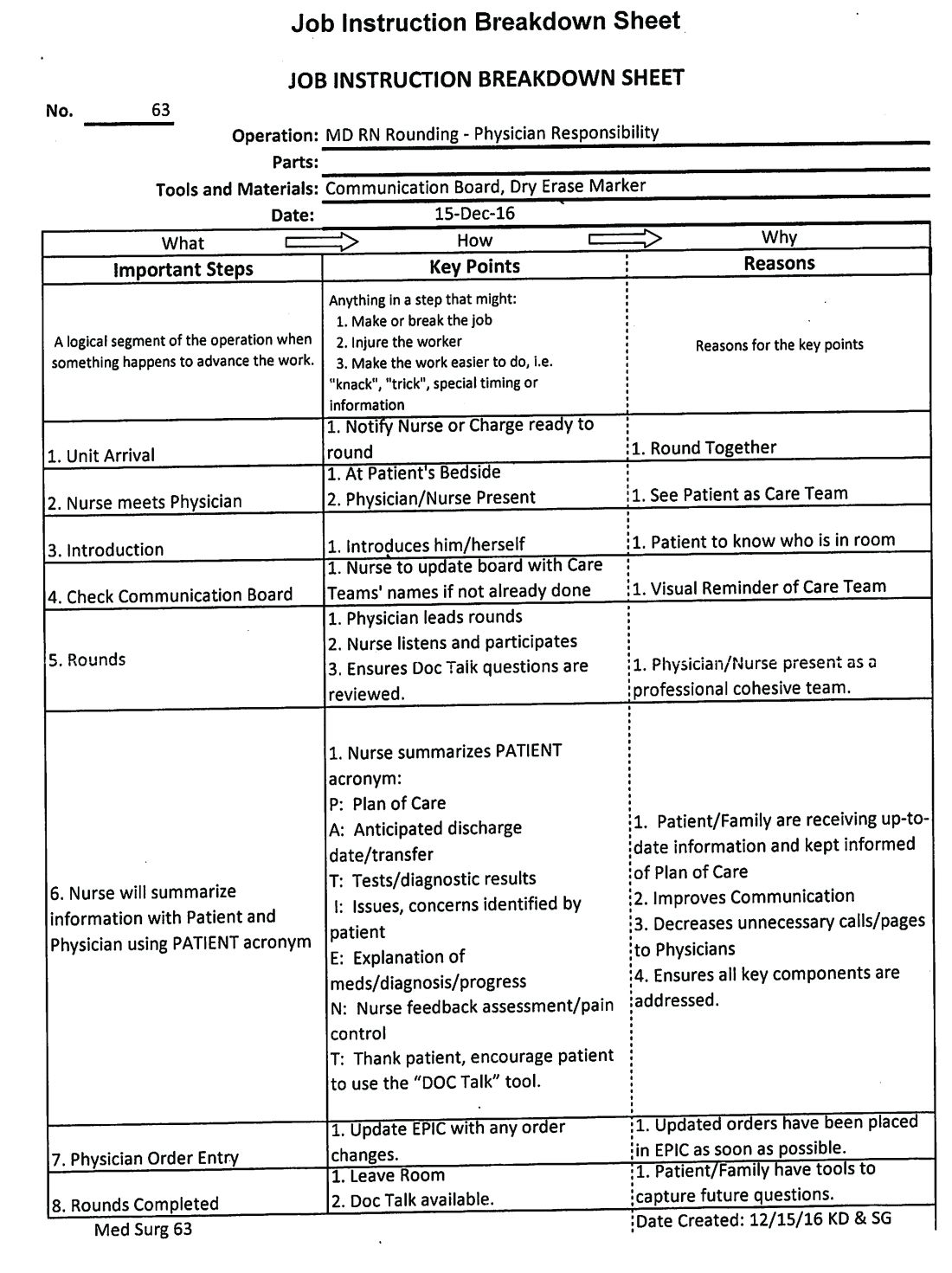

This process was repeated at other hospitals in the system once a standardized work flow was created (See Image 1). This initiative was next presented to the health system board of directors, who agreed that nurse-physician rounding should be the standard of care across our health system. Through partnership and collaboration with the IT department, we developed a tool to track nurse-physician rounding through our EHR system, which gave accountability to both physicians and nurses.

In conclusion, improved communication by timely nurse-physician rounding can lead to better outcomes for patients and also reduce costs and improve patient and staff experience, advancing the Quadruple Aim. Moving forward to build and sustain this work flow, we plan to continue nurse-physician collaboration across the health system consistently and for all areas of acute care operations.

Explaining the “Why,” sharing data on the benefits of the model, and reinforcing documentation of the rounding in our EHR are some steps we have put into action at leadership and staff meetings to sustain the activity. We are soliciting feedback, as well as monitoring and identifying any unaddressed barriers during rounding. Addition of this process measure to our quality improvement bonus opportunity also has helped to sustain performance from our teams.

Dr. Laufer is system medical director of hospital medicine and transitional care at Lee Health in Ft. Myers, Fla. Dr. Prasad is chief medical officer of Lee Physician Group, Ft. Myers, Fla.

References

1. Leape LL et al. Five years after to err is human: What we have learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384-90.

2. Sutcliffe KM et al. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-94.

3. Manojlovich M. Reframing communication with physicians as sensemaking. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Oct-Dec;28(4):295-303.

4. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care unit by implementing daily goals. Crit Care Nurse. 2009 Dec;29(6):58-69.

5. Asthon J et al. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meeting aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005 Oct;11(5):206-13.

6. Lancaster G et al. Interdisciplinary Communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015 May;47(3):275-84.

7. McIntosh N et al. Impact of provider coordination on nurse and physician perception of patient care quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014 Jul-Sep;29(3):269-79.

8. Jo M et al. An organizational assessment of disruptive clinical behavior. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Apr-Jun;28(2):110-21.

9. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, 2010.

10. O’Connor P et al. A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016 Jun;28(3):339-45.

11. Manojlovich M. Nurse/Physician communication through a sense making lens. Med Care. 2010 Nov;48(11):941-6.

12. Monash B et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):143-9.

13. O’Leary KJ et al. Effect of patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):921-8.

14. Dutton RP et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003 Nov;55(5):913-9.

15. Manojlovich M et al. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):536-43.

16. Ramirez J et al. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016 Feb;109(2):112-5.

17. Sollami A et al. Nurse-Physician collaboration: A meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprof Care. 2015 May;29(3):223-9.

18. House S et al. Nurses and physicians perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Adm. 2017 Mar;47(3):165-71.

19. Townsend-Gervis M et al. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communications reduce re-admissions and improve some patients’ outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014 Aug;36(7):917-28.

20. The Joint Commission. Sentinel Events. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event.aspx. Accessed Oct 2017.

21. Bodenheimer T et al. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):573-6.

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12

Some data suggest that patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients have no effect on patient perceptions or their satisfaction with care.13 However, we felt that collaboration among a multidisciplinary team would help us achieve better outcomes. For example, our patients would perceive the care team (MD-RN) as a cohesive unit, and in turn gain trust in the members of the treatment team, as found by Nathalie McIntosh, PhD, et al and by Jason Ramirez, MD.7,16 Our vision was to empower nurses to be advocates for patients and their family members as they navigated their acute care admission. Nurses could also support physicians by communicating the physicians’ care plans to families and patients. After rounding with the physician, the nurse would be part of the decision-making process and care planning.17

Every rounding session had discharge planning and hospital stay expectations that were shared with the patient and nurse, who could then partner with case managers and social workers, which would streamline and reduce length of stay.14 We hoped rounding would also decrease the number of nurse pages to clarify or question orders. This would, in turn, improve daily work flow for the physicians and the nursing team with improvements in employee satisfaction scores.15 A study also has demonstrated a reduction in readmission rates from nurse-physician rounding.19

A disconnect in communication and trust between physicians and the nursing staff was reflected in low patient experience scores and perceived quality of care received during in-hospital stay. Gwendolyn Lancaster, EdD, MSN, RN, CCRN, et al, as well as a Joint Commission report, demonstrated how a lack of communication and poor team dynamics can translate to poor patient experience and be a major cause for sentinel events.6,20 Artificial, forced hierarchies and role perception among health care team members led to frustration, hostility, and distrust, which compromises quality and patient safety.1

One of our biggest challenges when we started this project was explaining the “Why” to the hospitalist group and nursing staff. Physicians were used to being the dominant partner in the team. Partnering with and engaging nurses in shared decision making and care planning was a seismic shift in culture and work flow within the care team. Early gains helped skeptical team members begin to understand the value in nurse-physician rounding. Near universal adoption of the rounding process at Lee Health has caused improvements in the working relationship and trust among the health care professionals. We have seen improvements in utilization management, as well as appropriateness and timeliness of resource use, because of better communication and understanding of care plans by nursing and physicians. Collaboration with specialists and alignment in care planning are other gains. Hospitalists and nurses are both very satisfied with the decrease in the number of pages during the day, and this has lowered stressors on health care teams.

How we did it

Nurse-physician rounding is a proven method to improve collaboration, communication, and relationships among health care team members in acute care facilities. In the complex health care challenges faced today, this improved work flow for taking care of patients can help advance the Quadruple Aim of high quality, low cost, improved patient experience, physician, and staff satisfaction.21

Lee Health System includes four facilities in Lee County, with a total of 1,216 licensed adult acute care beds. The pilot project was started in 2014.

Initially the vice president of nursing and the hospitalist medical director met to create an education plan for nurses and physicians. We chose one adult medicine unit to pilot the project because there already existed a closely knit nursing and hospitalist team. In our facility there is no strict geographical rounding; each hospitalist carries between three and six patients in the unit. As a first step, a nurse floor assignment sheet was faxed in the morning to the hospitalist office with the direct phone numbers of the nurses. The unit clerk, using physician assignments in the EHR, teamed up the physician and nurses for rounding. Once the physician arrived at the unit, he or she checked in with the unit clerk, who alerted nurses that the hospitalist was available on the floor to commence rounding. If the primary nurse was unavailable because of other duties or breaks, the charge nurse rounded with the physician.

Once in the room with the patient, the duo introduced themselves as members of the treatment team and acknowledged the patient’s needs. During the visit, care plans and treatment were reviewed, the patient’s questions were answered, a physical exam was completed, and lab and imaging results were discussed; the nurse also helped raise questions he or she had received from family members so answers could be communicated to the family later. Patients appreciated knowing that their physicians and nurses were working together as a team for their safety and recovery. During the visit, care was taken to focus specially on the course of hospitalization and discharge planning.

We tracked the rounding with a manual paper process maintained by the charge nurse. Our initial rounding rates were 30%-40%, and we continued to promote this initiative to the team, and eventually the importance and value of these rounds caught on with both nurses and physicians, and now our current average rounding rate is 90%. We then decided to scale this to all units in the hospital.

This process was repeated at other hospitals in the system once a standardized work flow was created (See Image 1). This initiative was next presented to the health system board of directors, who agreed that nurse-physician rounding should be the standard of care across our health system. Through partnership and collaboration with the IT department, we developed a tool to track nurse-physician rounding through our EHR system, which gave accountability to both physicians and nurses.

In conclusion, improved communication by timely nurse-physician rounding can lead to better outcomes for patients and also reduce costs and improve patient and staff experience, advancing the Quadruple Aim. Moving forward to build and sustain this work flow, we plan to continue nurse-physician collaboration across the health system consistently and for all areas of acute care operations.

Explaining the “Why,” sharing data on the benefits of the model, and reinforcing documentation of the rounding in our EHR are some steps we have put into action at leadership and staff meetings to sustain the activity. We are soliciting feedback, as well as monitoring and identifying any unaddressed barriers during rounding. Addition of this process measure to our quality improvement bonus opportunity also has helped to sustain performance from our teams.

Dr. Laufer is system medical director of hospital medicine and transitional care at Lee Health in Ft. Myers, Fla. Dr. Prasad is chief medical officer of Lee Physician Group, Ft. Myers, Fla.

References

1. Leape LL et al. Five years after to err is human: What we have learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384-90.

2. Sutcliffe KM et al. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-94.

3. Manojlovich M. Reframing communication with physicians as sensemaking. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Oct-Dec;28(4):295-303.

4. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care unit by implementing daily goals. Crit Care Nurse. 2009 Dec;29(6):58-69.

5. Asthon J et al. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meeting aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005 Oct;11(5):206-13.

6. Lancaster G et al. Interdisciplinary Communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015 May;47(3):275-84.

7. McIntosh N et al. Impact of provider coordination on nurse and physician perception of patient care quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014 Jul-Sep;29(3):269-79.

8. Jo M et al. An organizational assessment of disruptive clinical behavior. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Apr-Jun;28(2):110-21.

9. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, 2010.

10. O’Connor P et al. A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016 Jun;28(3):339-45.

11. Manojlovich M. Nurse/Physician communication through a sense making lens. Med Care. 2010 Nov;48(11):941-6.

12. Monash B et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):143-9.

13. O’Leary KJ et al. Effect of patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):921-8.

14. Dutton RP et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003 Nov;55(5):913-9.

15. Manojlovich M et al. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):536-43.

16. Ramirez J et al. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016 Feb;109(2):112-5.

17. Sollami A et al. Nurse-Physician collaboration: A meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprof Care. 2015 May;29(3):223-9.

18. House S et al. Nurses and physicians perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Adm. 2017 Mar;47(3):165-71.

19. Townsend-Gervis M et al. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communications reduce re-admissions and improve some patients’ outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014 Aug;36(7):917-28.

20. The Joint Commission. Sentinel Events. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event.aspx. Accessed Oct 2017.

21. Bodenheimer T et al. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):573-6.

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12

Some data suggest that patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients have no effect on patient perceptions or their satisfaction with care.13 However, we felt that collaboration among a multidisciplinary team would help us achieve better outcomes. For example, our patients would perceive the care team (MD-RN) as a cohesive unit, and in turn gain trust in the members of the treatment team, as found by Nathalie McIntosh, PhD, et al and by Jason Ramirez, MD.7,16 Our vision was to empower nurses to be advocates for patients and their family members as they navigated their acute care admission. Nurses could also support physicians by communicating the physicians’ care plans to families and patients. After rounding with the physician, the nurse would be part of the decision-making process and care planning.17

Every rounding session had discharge planning and hospital stay expectations that were shared with the patient and nurse, who could then partner with case managers and social workers, which would streamline and reduce length of stay.14 We hoped rounding would also decrease the number of nurse pages to clarify or question orders. This would, in turn, improve daily work flow for the physicians and the nursing team with improvements in employee satisfaction scores.15 A study also has demonstrated a reduction in readmission rates from nurse-physician rounding.19

A disconnect in communication and trust between physicians and the nursing staff was reflected in low patient experience scores and perceived quality of care received during in-hospital stay. Gwendolyn Lancaster, EdD, MSN, RN, CCRN, et al, as well as a Joint Commission report, demonstrated how a lack of communication and poor team dynamics can translate to poor patient experience and be a major cause for sentinel events.6,20 Artificial, forced hierarchies and role perception among health care team members led to frustration, hostility, and distrust, which compromises quality and patient safety.1

One of our biggest challenges when we started this project was explaining the “Why” to the hospitalist group and nursing staff. Physicians were used to being the dominant partner in the team. Partnering with and engaging nurses in shared decision making and care planning was a seismic shift in culture and work flow within the care team. Early gains helped skeptical team members begin to understand the value in nurse-physician rounding. Near universal adoption of the rounding process at Lee Health has caused improvements in the working relationship and trust among the health care professionals. We have seen improvements in utilization management, as well as appropriateness and timeliness of resource use, because of better communication and understanding of care plans by nursing and physicians. Collaboration with specialists and alignment in care planning are other gains. Hospitalists and nurses are both very satisfied with the decrease in the number of pages during the day, and this has lowered stressors on health care teams.

How we did it

Nurse-physician rounding is a proven method to improve collaboration, communication, and relationships among health care team members in acute care facilities. In the complex health care challenges faced today, this improved work flow for taking care of patients can help advance the Quadruple Aim of high quality, low cost, improved patient experience, physician, and staff satisfaction.21

Lee Health System includes four facilities in Lee County, with a total of 1,216 licensed adult acute care beds. The pilot project was started in 2014.

Initially the vice president of nursing and the hospitalist medical director met to create an education plan for nurses and physicians. We chose one adult medicine unit to pilot the project because there already existed a closely knit nursing and hospitalist team. In our facility there is no strict geographical rounding; each hospitalist carries between three and six patients in the unit. As a first step, a nurse floor assignment sheet was faxed in the morning to the hospitalist office with the direct phone numbers of the nurses. The unit clerk, using physician assignments in the EHR, teamed up the physician and nurses for rounding. Once the physician arrived at the unit, he or she checked in with the unit clerk, who alerted nurses that the hospitalist was available on the floor to commence rounding. If the primary nurse was unavailable because of other duties or breaks, the charge nurse rounded with the physician.

Once in the room with the patient, the duo introduced themselves as members of the treatment team and acknowledged the patient’s needs. During the visit, care plans and treatment were reviewed, the patient’s questions were answered, a physical exam was completed, and lab and imaging results were discussed; the nurse also helped raise questions he or she had received from family members so answers could be communicated to the family later. Patients appreciated knowing that their physicians and nurses were working together as a team for their safety and recovery. During the visit, care was taken to focus specially on the course of hospitalization and discharge planning.

We tracked the rounding with a manual paper process maintained by the charge nurse. Our initial rounding rates were 30%-40%, and we continued to promote this initiative to the team, and eventually the importance and value of these rounds caught on with both nurses and physicians, and now our current average rounding rate is 90%. We then decided to scale this to all units in the hospital.

This process was repeated at other hospitals in the system once a standardized work flow was created (See Image 1). This initiative was next presented to the health system board of directors, who agreed that nurse-physician rounding should be the standard of care across our health system. Through partnership and collaboration with the IT department, we developed a tool to track nurse-physician rounding through our EHR system, which gave accountability to both physicians and nurses.

In conclusion, improved communication by timely nurse-physician rounding can lead to better outcomes for patients and also reduce costs and improve patient and staff experience, advancing the Quadruple Aim. Moving forward to build and sustain this work flow, we plan to continue nurse-physician collaboration across the health system consistently and for all areas of acute care operations.

Explaining the “Why,” sharing data on the benefits of the model, and reinforcing documentation of the rounding in our EHR are some steps we have put into action at leadership and staff meetings to sustain the activity. We are soliciting feedback, as well as monitoring and identifying any unaddressed barriers during rounding. Addition of this process measure to our quality improvement bonus opportunity also has helped to sustain performance from our teams.

Dr. Laufer is system medical director of hospital medicine and transitional care at Lee Health in Ft. Myers, Fla. Dr. Prasad is chief medical officer of Lee Physician Group, Ft. Myers, Fla.

References

1. Leape LL et al. Five years after to err is human: What we have learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384-90.

2. Sutcliffe KM et al. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-94.

3. Manojlovich M. Reframing communication with physicians as sensemaking. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Oct-Dec;28(4):295-303.

4. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care unit by implementing daily goals. Crit Care Nurse. 2009 Dec;29(6):58-69.

5. Asthon J et al. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meeting aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005 Oct;11(5):206-13.

6. Lancaster G et al. Interdisciplinary Communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015 May;47(3):275-84.

7. McIntosh N et al. Impact of provider coordination on nurse and physician perception of patient care quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014 Jul-Sep;29(3):269-79.

8. Jo M et al. An organizational assessment of disruptive clinical behavior. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Apr-Jun;28(2):110-21.

9. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, 2010.

10. O’Connor P et al. A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016 Jun;28(3):339-45.

11. Manojlovich M. Nurse/Physician communication through a sense making lens. Med Care. 2010 Nov;48(11):941-6.

12. Monash B et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):143-9.

13. O’Leary KJ et al. Effect of patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):921-8.

14. Dutton RP et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003 Nov;55(5):913-9.

15. Manojlovich M et al. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):536-43.

16. Ramirez J et al. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016 Feb;109(2):112-5.

17. Sollami A et al. Nurse-Physician collaboration: A meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprof Care. 2015 May;29(3):223-9.

18. House S et al. Nurses and physicians perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Adm. 2017 Mar;47(3):165-71.

19. Townsend-Gervis M et al. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communications reduce re-admissions and improve some patients’ outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014 Aug;36(7):917-28.

20. The Joint Commission. Sentinel Events. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event.aspx. Accessed Oct 2017.

21. Bodenheimer T et al. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):573-6.