User login

Long-term assessment of suicide risk and ideation in older adults may help identify distinct ideation patterns and predict potential future suicidal behavior, new research suggests.

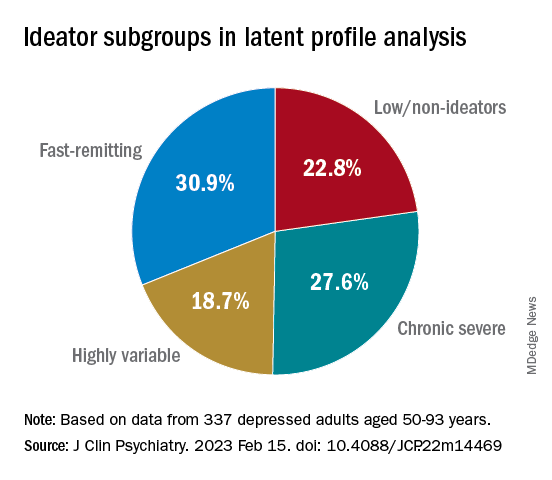

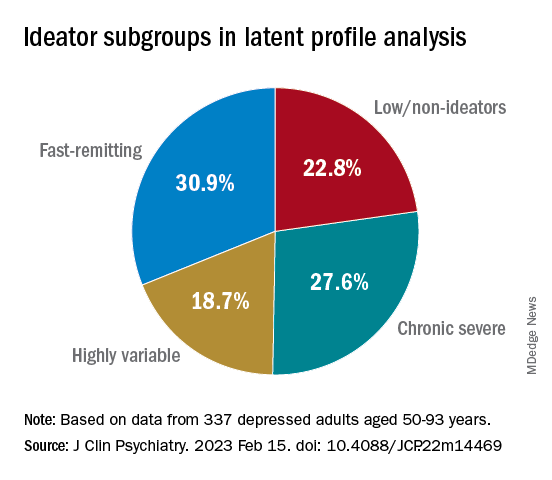

Investigators studied over 300 older adults, assessing suicidal ideation and behavior for up to 14 years at least once annually. They then identified four suicidal ideation profiles.

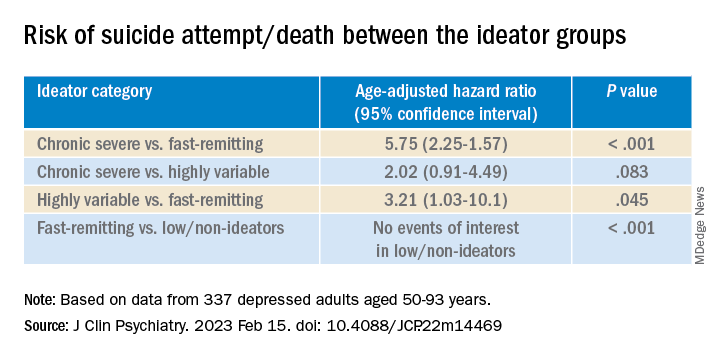

They found that In turn, fast-remitting ideators were at higher risk in comparison to low/nonideators with no attempts or suicide.

Chronic severe ideators also showed the most severe levels of dysfunction across personality, social characteristics, and impulsivity measures, while highly variable and fast-remitting ideators displayed more specific deficits.

“We identified longitudinal ideation profiles that convey differential risk of future suicidal behavior to help clinicians recognize high suicide risk patients for preventing suicide,” said lead author Hanga Galfalvy, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

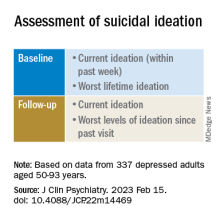

“Clinicians should repeatedly assess suicidal ideation and ask not only about current ideation but also about the worst ideation since the last visit [because] similar levels of ideation during a single assessment can belong to very different risk profiles,” said Dr. Galfalvy, also a professor of biostatistics and a coinvestigator in the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention at Columbia University.

The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Vulnerable population

“Older adults in most countries, including the U.S., are at the highest risk of dying of suicide out of all age groups,” said Dr. Galfalvy. “A significant number of depressed older adults experience thoughts of killing themselves, but fortunately, only a few transition from suicidal thoughts to behavior.”

Senior author Katalin Szanto, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview that currently established clinical and psychosocial suicide risk factors have “low predictive value and provide little insight into the high suicide rate in the elderly.”

These traditional risk factors “poorly distinguish between suicide ideators and suicide attempters and do not take into consideration the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Szanto, principal investigator at the University of Pittsburgh’s Longitudinal research Program in Late-Life Suicide, where the study was conducted.

“Suicidal ideation measured at one time point – current or lifetime – may not be enough to accurately predict suicide risk,” the investigators wrote.

The current study, a collaboration between investigators from the Longitudinal Research Program in Late-Life Suicide and the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention, investigates “profiles of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients with late-life depression over a longer period of time,” Dr. Galfalvy said.

The researchers used latent profile analysis (LPA) in a cohort of adults with nonpsychotic unipolar depression (aged 50-93 years; n = 337; mean age, 65.12 years) to “identify distinct ideation profiles and their clinical correlates” and to “test the profiles’ association with the risk of suicidal behavior before and during follow-up.”

LPA is “a data-driven method of grouping individuals into subgroups, based on quantitative characteristics,” Dr. Galfalvy explained.

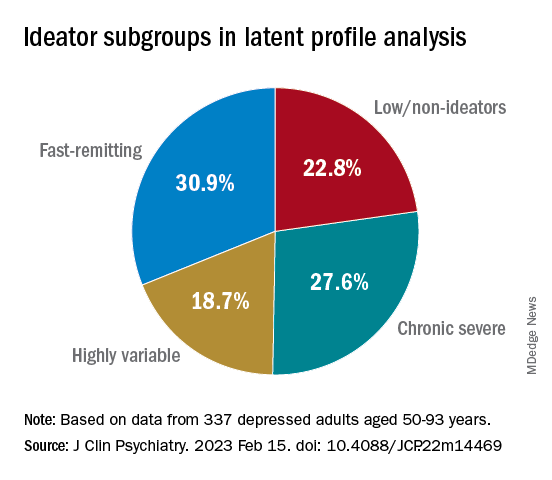

The LPA yielded four profiles of ideation.

At baseline, the researchers assessed the presence or absence of suicidal behavior history and the number and lethality of attempts. They prospectively assessed suicidal ideation and attempts at least once annually thereafter over a period ranging from 3 months to 14 years (median, 3 years; IQR, 1.6-4 years).

At baseline and at follow-ups, they assessed ideation severity.

They also assessed depression severity, impulsivity, and personality measures, as well as perception of social support, social problem solving, cognitive performance, and physical comorbidities.

Personalized prevention

Of the original cohort, 92 patients died during the follow-up period, with 13 dying of suicide (or suspected suicide).

Over half (60%) of the chronic severe as well as the highly variable groups and almost half (48%) of the fast-remitting group had a history of past suicide attempt – all significantly higher than the low-nonideators (0%).

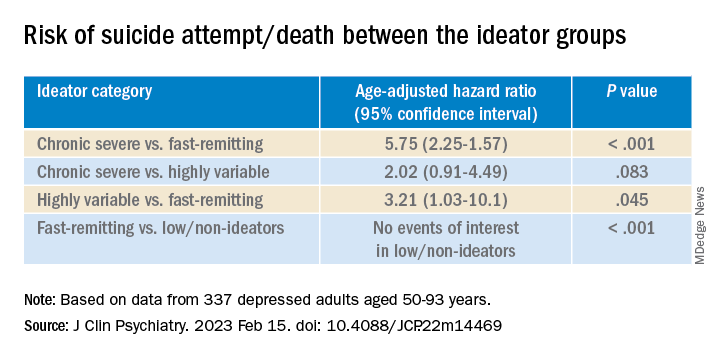

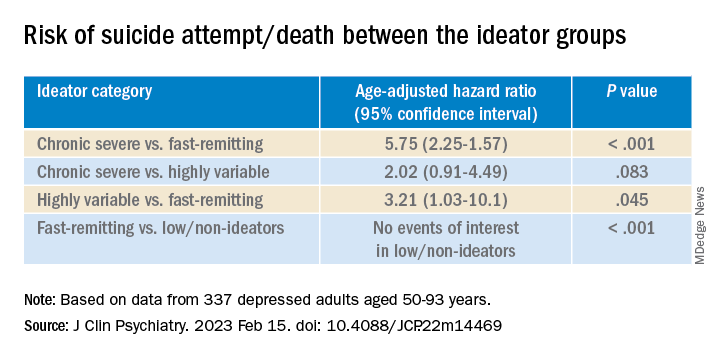

Despite comparable current ideation severity at baseline, the risk of suicide attempt/death was greater for chronic severe ideators versus fast-remitting ideators, but not greater than for highly variable ideators. On the other hand, highly variable ideators were at greater risk, compared with fast-remitting ideators.

Cognitive factors “did not significantly discriminate between the ideation profiles, although ... lower global cognitive performance predicted suicidal behavior during follow-up,” the authors wrote.

This finding “aligns with prior studies indicating that late-life suicidal behavior but not ideation may be related to cognition ... and instead, ideation and cognition may act as independent risk factors for suicidal behavior,” they added.

“Patients in the fluctuating ideator group generally had moderate or high levels of worst suicidal ideation between visits, but not when asked about current ideation levels at the time of the follow-up assessment,” Dr. Galfalvy noted. “For them, the time frame of the question made a difference as to the level of ideation reported.”

The study “identified several clinical differences among these subgroups which could lead to more personalized suicide prevention efforts and further research into the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” she suggested.

New insight

Commenting on the study, Ari Cuperfain, MD, of the University of Toronto said the study “adds to the nuanced understanding of how changes in suicidal ideation over time can lead to suicidal actions and behavior.”

The study “sheds light on the notion of how older adults who die by suicide can demonstrate a greater degree of premeditated intent relative to younger cohorts, with chronic severe ideators portending the highest risk for suicide in this sample,” added Dr. Cuperfain, who was not involved with the current research.

“Overall, the paper highlights the importance of both screening for current levels of suicidal ideation in addition to the evolution of suicidal ideation in developing a risk assessment and in finding interventions to reduce this risk when it is most prominent,” he stated.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Cuperfain disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term assessment of suicide risk and ideation in older adults may help identify distinct ideation patterns and predict potential future suicidal behavior, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 300 older adults, assessing suicidal ideation and behavior for up to 14 years at least once annually. They then identified four suicidal ideation profiles.

They found that In turn, fast-remitting ideators were at higher risk in comparison to low/nonideators with no attempts or suicide.

Chronic severe ideators also showed the most severe levels of dysfunction across personality, social characteristics, and impulsivity measures, while highly variable and fast-remitting ideators displayed more specific deficits.

“We identified longitudinal ideation profiles that convey differential risk of future suicidal behavior to help clinicians recognize high suicide risk patients for preventing suicide,” said lead author Hanga Galfalvy, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

“Clinicians should repeatedly assess suicidal ideation and ask not only about current ideation but also about the worst ideation since the last visit [because] similar levels of ideation during a single assessment can belong to very different risk profiles,” said Dr. Galfalvy, also a professor of biostatistics and a coinvestigator in the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention at Columbia University.

The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Vulnerable population

“Older adults in most countries, including the U.S., are at the highest risk of dying of suicide out of all age groups,” said Dr. Galfalvy. “A significant number of depressed older adults experience thoughts of killing themselves, but fortunately, only a few transition from suicidal thoughts to behavior.”

Senior author Katalin Szanto, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview that currently established clinical and psychosocial suicide risk factors have “low predictive value and provide little insight into the high suicide rate in the elderly.”

These traditional risk factors “poorly distinguish between suicide ideators and suicide attempters and do not take into consideration the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Szanto, principal investigator at the University of Pittsburgh’s Longitudinal research Program in Late-Life Suicide, where the study was conducted.

“Suicidal ideation measured at one time point – current or lifetime – may not be enough to accurately predict suicide risk,” the investigators wrote.

The current study, a collaboration between investigators from the Longitudinal Research Program in Late-Life Suicide and the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention, investigates “profiles of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients with late-life depression over a longer period of time,” Dr. Galfalvy said.

The researchers used latent profile analysis (LPA) in a cohort of adults with nonpsychotic unipolar depression (aged 50-93 years; n = 337; mean age, 65.12 years) to “identify distinct ideation profiles and their clinical correlates” and to “test the profiles’ association with the risk of suicidal behavior before and during follow-up.”

LPA is “a data-driven method of grouping individuals into subgroups, based on quantitative characteristics,” Dr. Galfalvy explained.

The LPA yielded four profiles of ideation.

At baseline, the researchers assessed the presence or absence of suicidal behavior history and the number and lethality of attempts. They prospectively assessed suicidal ideation and attempts at least once annually thereafter over a period ranging from 3 months to 14 years (median, 3 years; IQR, 1.6-4 years).

At baseline and at follow-ups, they assessed ideation severity.

They also assessed depression severity, impulsivity, and personality measures, as well as perception of social support, social problem solving, cognitive performance, and physical comorbidities.

Personalized prevention

Of the original cohort, 92 patients died during the follow-up period, with 13 dying of suicide (or suspected suicide).

Over half (60%) of the chronic severe as well as the highly variable groups and almost half (48%) of the fast-remitting group had a history of past suicide attempt – all significantly higher than the low-nonideators (0%).

Despite comparable current ideation severity at baseline, the risk of suicide attempt/death was greater for chronic severe ideators versus fast-remitting ideators, but not greater than for highly variable ideators. On the other hand, highly variable ideators were at greater risk, compared with fast-remitting ideators.

Cognitive factors “did not significantly discriminate between the ideation profiles, although ... lower global cognitive performance predicted suicidal behavior during follow-up,” the authors wrote.

This finding “aligns with prior studies indicating that late-life suicidal behavior but not ideation may be related to cognition ... and instead, ideation and cognition may act as independent risk factors for suicidal behavior,” they added.

“Patients in the fluctuating ideator group generally had moderate or high levels of worst suicidal ideation between visits, but not when asked about current ideation levels at the time of the follow-up assessment,” Dr. Galfalvy noted. “For them, the time frame of the question made a difference as to the level of ideation reported.”

The study “identified several clinical differences among these subgroups which could lead to more personalized suicide prevention efforts and further research into the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” she suggested.

New insight

Commenting on the study, Ari Cuperfain, MD, of the University of Toronto said the study “adds to the nuanced understanding of how changes in suicidal ideation over time can lead to suicidal actions and behavior.”

The study “sheds light on the notion of how older adults who die by suicide can demonstrate a greater degree of premeditated intent relative to younger cohorts, with chronic severe ideators portending the highest risk for suicide in this sample,” added Dr. Cuperfain, who was not involved with the current research.

“Overall, the paper highlights the importance of both screening for current levels of suicidal ideation in addition to the evolution of suicidal ideation in developing a risk assessment and in finding interventions to reduce this risk when it is most prominent,” he stated.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Cuperfain disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term assessment of suicide risk and ideation in older adults may help identify distinct ideation patterns and predict potential future suicidal behavior, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 300 older adults, assessing suicidal ideation and behavior for up to 14 years at least once annually. They then identified four suicidal ideation profiles.

They found that In turn, fast-remitting ideators were at higher risk in comparison to low/nonideators with no attempts or suicide.

Chronic severe ideators also showed the most severe levels of dysfunction across personality, social characteristics, and impulsivity measures, while highly variable and fast-remitting ideators displayed more specific deficits.

“We identified longitudinal ideation profiles that convey differential risk of future suicidal behavior to help clinicians recognize high suicide risk patients for preventing suicide,” said lead author Hanga Galfalvy, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

“Clinicians should repeatedly assess suicidal ideation and ask not only about current ideation but also about the worst ideation since the last visit [because] similar levels of ideation during a single assessment can belong to very different risk profiles,” said Dr. Galfalvy, also a professor of biostatistics and a coinvestigator in the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention at Columbia University.

The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Vulnerable population

“Older adults in most countries, including the U.S., are at the highest risk of dying of suicide out of all age groups,” said Dr. Galfalvy. “A significant number of depressed older adults experience thoughts of killing themselves, but fortunately, only a few transition from suicidal thoughts to behavior.”

Senior author Katalin Szanto, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview that currently established clinical and psychosocial suicide risk factors have “low predictive value and provide little insight into the high suicide rate in the elderly.”

These traditional risk factors “poorly distinguish between suicide ideators and suicide attempters and do not take into consideration the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Szanto, principal investigator at the University of Pittsburgh’s Longitudinal research Program in Late-Life Suicide, where the study was conducted.

“Suicidal ideation measured at one time point – current or lifetime – may not be enough to accurately predict suicide risk,” the investigators wrote.

The current study, a collaboration between investigators from the Longitudinal Research Program in Late-Life Suicide and the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention, investigates “profiles of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients with late-life depression over a longer period of time,” Dr. Galfalvy said.

The researchers used latent profile analysis (LPA) in a cohort of adults with nonpsychotic unipolar depression (aged 50-93 years; n = 337; mean age, 65.12 years) to “identify distinct ideation profiles and their clinical correlates” and to “test the profiles’ association with the risk of suicidal behavior before and during follow-up.”

LPA is “a data-driven method of grouping individuals into subgroups, based on quantitative characteristics,” Dr. Galfalvy explained.

The LPA yielded four profiles of ideation.

At baseline, the researchers assessed the presence or absence of suicidal behavior history and the number and lethality of attempts. They prospectively assessed suicidal ideation and attempts at least once annually thereafter over a period ranging from 3 months to 14 years (median, 3 years; IQR, 1.6-4 years).

At baseline and at follow-ups, they assessed ideation severity.

They also assessed depression severity, impulsivity, and personality measures, as well as perception of social support, social problem solving, cognitive performance, and physical comorbidities.

Personalized prevention

Of the original cohort, 92 patients died during the follow-up period, with 13 dying of suicide (or suspected suicide).

Over half (60%) of the chronic severe as well as the highly variable groups and almost half (48%) of the fast-remitting group had a history of past suicide attempt – all significantly higher than the low-nonideators (0%).

Despite comparable current ideation severity at baseline, the risk of suicide attempt/death was greater for chronic severe ideators versus fast-remitting ideators, but not greater than for highly variable ideators. On the other hand, highly variable ideators were at greater risk, compared with fast-remitting ideators.

Cognitive factors “did not significantly discriminate between the ideation profiles, although ... lower global cognitive performance predicted suicidal behavior during follow-up,” the authors wrote.

This finding “aligns with prior studies indicating that late-life suicidal behavior but not ideation may be related to cognition ... and instead, ideation and cognition may act as independent risk factors for suicidal behavior,” they added.

“Patients in the fluctuating ideator group generally had moderate or high levels of worst suicidal ideation between visits, but not when asked about current ideation levels at the time of the follow-up assessment,” Dr. Galfalvy noted. “For them, the time frame of the question made a difference as to the level of ideation reported.”

The study “identified several clinical differences among these subgroups which could lead to more personalized suicide prevention efforts and further research into the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” she suggested.

New insight

Commenting on the study, Ari Cuperfain, MD, of the University of Toronto said the study “adds to the nuanced understanding of how changes in suicidal ideation over time can lead to suicidal actions and behavior.”

The study “sheds light on the notion of how older adults who die by suicide can demonstrate a greater degree of premeditated intent relative to younger cohorts, with chronic severe ideators portending the highest risk for suicide in this sample,” added Dr. Cuperfain, who was not involved with the current research.

“Overall, the paper highlights the importance of both screening for current levels of suicidal ideation in addition to the evolution of suicidal ideation in developing a risk assessment and in finding interventions to reduce this risk when it is most prominent,” he stated.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Cuperfain disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY