User login

Since the first baby was born after a uterus transplantation in Sweden in 2014, uterus transplantation has been rapidly transitioning toward clinical reality.1 Several teams in the United States and multiple teams worldwide have performed the procedure, with the total number of worldwide surgeries performed nearing 100.

Uterus transplantation is the first and only true treatment for women with absolute uterine factor infertility – estimated to affect 1 in 500 women – and is filling an unmet need for this population of women. Women who have sought participation in uterus transplantation research have had complex and meaningful reasons and motivations for doing so.2 Combined with an accumulation of successful pregnancies, this makes continued research and technical improvement a worthy endeavor.

Most of the births thus far have occurred through the living-donor model; the initial Swedish trial involved nine women, seven of whom completed the procedure with viable transplants from living donors, and gave birth to eight healthy children. (Two required hysterectomy prior to attempted embryo transfer.3)

The Cleveland Clinic opted to build its first – and still ongoing – trial focusing on deceased-donor uterus transplants on the premise that such an approach obviates any risk to the donor and presents the fewest ethical challenges at the current time. Of eight uterus transplants performed thus far at the Cleveland Clinic, there have been three live births and two graft failures. As of early 2021, there was one ongoing pregnancy and two patients in preparation for embryo transfer.

Thus far, neither the living- nor deceased-donor model of uterus transplantation has been demonstrated to be superior. However, as data accrues from deceased donor studies, we will be able to more directly compare outcomes.

In the meantime, alongside a rapid ascent of clinical landmarks – the first live birth in the United States from living-donor uterus transplantation in 2017 at Baylor University Medical Center in Houston,4 for instance, and the first live birth in the United States from deceased-donor uterus transplantation in 2019 at the Cleveland Clinic – there have been significant improvements in surgical retrieval of the uterus and in the optimization of graft performance.5

Most notably, the utero-ovarian vein has been used successfully in living donors to achieve venous drainage of the graft. This has lessened the risks of deep pelvic dissection in the living donor and made the transition to laparoscopic and robotic approaches in the living donor much easier.

Donor procurement, venous drainage

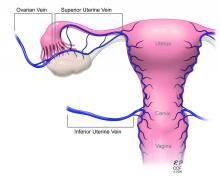

Adequate circulatory inflow and outflow for the transplanted uterus are essential both for the prevention of ischemia and thrombosis, which have been major causes of graft failure, and for meeting the increased demands of blood flow during pregnancy. Of the two, the outflow is the more challenging component.

Venous drainage traditionally has been accomplished through the use of the uterine veins, which drain into the internal iliac veins; often the vascular graft will include a portion of the internal iliac vessel which can be connected via anastomoses to the external iliac vein classically in deceased donors. Typically, the gynecologic surgeon on the team performs the vaginal anastomosis and suspension of the uterus, while the transplant surgeons perform the venous and arterial anastomoses.

In the living-donor model, procurement and dissection of these often unpredictable and tortuous complexes in the deep pelvis – particularly the branching uterine veins that lie in close proximity to the ureter, bladder, other blood vessels, and rectum – can be risky. The anatomic variants in the uterine vein are numerous, and even in one patient, a comprehensive dissection on one side cannot be expected to be mirrored on the contralateral side.

In addition to the risk of injury to the donor, the anastomosis may be unsuccessful as the veins are thinly walled and challenging to suture. As such, multiple modifications have been developed, often adapted to the donor’s anatomy and the caliber and accessibility of vessels. Preoperative vascular imaging with CT and/or MRI may help to identify suitable candidates and also may facilitate presurgical planning of which vessels may be selected for use.

Recently, surgeons performing living-donor transplantations have successfully used the more accessible and less risky ovarian and/or utero-ovarian veins for venous anastomosis. In 2019, for instance, a team in Pune, India, reported laparoscopically dissecting the donor ovarian veins and a portion of the internal iliac artery, and completing anastomosis with bilateral donor internal iliac arteries to recipient internal iliac arteries, and bilateral donor ovarian veins to recipient external iliac veins.6 It is significant that these smaller-caliber vessels were found to able to support the uterus through pregnancy.

We must be cautious, however, to avoid removing donors’ ovaries. Oophorectomy for women in their 40s can result in significant long-term medical sequelae. Surgeons at Baylor have achieved at least one live birth after harvesting the donor’s utero-ovarian veins while conserving the ovaries – a significant advancement for the living-donor model.4

There is tremendous interest in developing minimally invasive approaches to further reduce living-donor risk. The Swedish team has completed a series of eight robotic hysterectomies in living-donor uterus transplantations as part of a second trial. Addressing the reality of a learning curve, their study was designed around a step-wise approach, mastering initial steps first – e.g., dissections of the uterovaginal fossa, arteries, and ureters – and ultimately converting to laparotomy.7 In the United States, Baylor University has now completed at least five completely robotic living-donor hysterectomies with complete vaginal extraction.

Published data on robotic surgery suggests that surgical access and perioperative visualization of the vessels may be improved. And as minimally invasive approaches are adopted and improved, the length of donor surgery – 10-13 hours of operating room time in the original Swedish series – should diminish, as should the morbidity associated with laparotomy.

Surgical acquisition of a uterine graft from a deceased donor diminishes concerns for injury to nearby structures. Therefore, although it is a technically similar procedure, a deceased-donor model allows more flexibility with the length, caliber, and number of vessels that can be used for anastomosis. The internal iliac vessels and even portions of the external iliac vessels and ovarian vessels can be used to allow maximum flexibility.8

Surgical technique for uterus recipients

For the recipient surgery, entry is achieved via a midline, vertical laparotomy. The external iliac vessels are exposed, and the sites of vascular anastomoses are identified. The peritoneal reflection of the bladder is identified and dissected away to expose the anterior vagina, and the vagina is opened to a diameter that matches the donor, typically using a monopolar electrosurgical cutting instrument.

The vault of the donor vagina will be attached to the recipient’s existing vagina or vaginal pouch. It is important to identify recipient vaginal mucosa and incorporate it into the vaginal anastomosis to reduce the risk of vaginal stricture. We recommend that the vaginal mucosa be tagged with PDS II sutures or grasped with allis clamps to prevent retraction.

Surgical teams have taken multiple approaches to vaginal anastomosis. The Cleveland Clinic has used both a running suture as well as a horizontal mattress stitch for closure. For the latter, a 30-inch double-armed 2.0 Vicryl allows for complete suturing of the recipient vagina – with eight stitches placed circumferentially – before the uterus is placed. Both ends of the suture are passed intra-abdominal to intravaginal in the recipient.9

Once the donor uterus is suspended, attention focuses on vascular anastomosis, with bilateral end-to-side anastomosis between the donor anterior division of the internal iliac arteries and the external iliac vessels of the recipient, and with venous drainage commonly achieved through the uterine veins draining into the internal or external iliac vein of the recipient. As mentioned, recent cases involving living donors have also demonstrated success with the use of ovarian and/or utero-ovarian veins. Care should be taken to avoid having tension or twisting across the anastomosis.

After adequate graft perfusion is confirmed, with the uterus turning from a dusky color to a pink and well-perfused organ, the vaginal anastomosis is completed, with the arms of the double-armed suture passed through the donor vagina, from intravaginal to intra-abdominal. Tension should be evenly spread along the recipient and donor vagina in order to reduce the formation of granulation tissue and the severity of future vaginal stricturing.

For uterine fixation, polypropylene sutures are placed between the graft uterosacral ligaments and recipient uterine rudiments, and between the graft round ligaments and the recipient pelvic side wall at the level of the deep inguinal ring.

Current uterus transplantation protocols require removal of the uterus after one or two live births are achieved, so that recipients will not be exposed to long-term immunosuppression.

Complications and controversies

Postoperative vaginal strictures can make embryo transfer difficult and are a common complication in both living- and deceased-donor models. The Cleveland Clinic team has applied techniques from vaginal reconstructive surgery to try to reduce the occurrence of postoperative strictures – mainly increasing attention paid to anastomosis tissue–site preparation and closure of the anastomosis using a tension-free interrupted suture technique, as described above.9 The jury is out on whether such changes are sufficient, and a more complete understanding of the causes of vaginal stricture is needed.

Other perioperative complications include infection and graft thrombosis, both of which typically result in urgent graft hysterectomy. During pregnancy, one of our patients experienced abnormal placentation, though this was not thought to be related to uterus transplantation.5

The U.S. Uterus Transplant Consortium (USUTC) is a group of active programs that are sharing ideas and outcomes and advocating for continued research in this rapidly developing field. Uterine transplants require collaboration with transplant surgery, transplant medicine, infectious disease, gynecologic surgery, high-risk obstetrics, and other specialties. While significant progress has been made in a short period of time, uterine transplantation is still in its early stages, and transplants should be done in institutions that have the capacity for mentorship, bioethical oversight, and long-term follow-up of donors, recipients, and offspring.

The USUTC has recently proposed guidelines for nomenclature related to operative technique, vascular anatomy, and uterine transplantation outcomes.10 It proposes standardizing the names for the four veins originating from the uterus (to eliminate current inconsistency), which will be important as optimal strategies for vascular anastomoses are discussed and determined.

In addition, the consortium is creating a registry for the rigorous collection of data on procedures and outcomes (from menstruation and pregnancy through delivery, graft removal, and long-term follow-up). A registry has also been proposed by the International Society for Uterine Transplantation.

A major question remains in our field: Is the living-donor or deceased-donor uterus transplant the best approach? Knowledge of the quality of the uterus is greater preoperatively within a living-donor model, but no matter how minimally invasive the technique, the donor still assumes some risk of prolonged surgery and extensive pelvic dissection for a transplant that is not lifesaving.

On the other hand, deceased-donor transplants require additional layers of organization and coordination, and the availability of suitable deceased-donor uteri will likely not be sufficient to meet the current demand. Many of us in the field believe that the future of uterine transplantation will involve some combination of living- and deceased-donor transplants – similar to other solid organ transplant programs.

Dr. Flyckt and Dr. Richards reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 2/2/21: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Richards' name in the photo caption.

References

1. Lancet. 2015;14:385:607-16.

2. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(1):23-5.

3. Transplantation. 2020;104(7):1312-5.

4. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1270-4.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(2):143-51.

6. J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:628-35.

7. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(9):1222-9.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(1):183.

9. Fertil Steril. 2020 Jul 16. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.017

10 Am J Transplant. 2020;20(12):3319-25.

Since the first baby was born after a uterus transplantation in Sweden in 2014, uterus transplantation has been rapidly transitioning toward clinical reality.1 Several teams in the United States and multiple teams worldwide have performed the procedure, with the total number of worldwide surgeries performed nearing 100.

Uterus transplantation is the first and only true treatment for women with absolute uterine factor infertility – estimated to affect 1 in 500 women – and is filling an unmet need for this population of women. Women who have sought participation in uterus transplantation research have had complex and meaningful reasons and motivations for doing so.2 Combined with an accumulation of successful pregnancies, this makes continued research and technical improvement a worthy endeavor.

Most of the births thus far have occurred through the living-donor model; the initial Swedish trial involved nine women, seven of whom completed the procedure with viable transplants from living donors, and gave birth to eight healthy children. (Two required hysterectomy prior to attempted embryo transfer.3)

The Cleveland Clinic opted to build its first – and still ongoing – trial focusing on deceased-donor uterus transplants on the premise that such an approach obviates any risk to the donor and presents the fewest ethical challenges at the current time. Of eight uterus transplants performed thus far at the Cleveland Clinic, there have been three live births and two graft failures. As of early 2021, there was one ongoing pregnancy and two patients in preparation for embryo transfer.

Thus far, neither the living- nor deceased-donor model of uterus transplantation has been demonstrated to be superior. However, as data accrues from deceased donor studies, we will be able to more directly compare outcomes.

In the meantime, alongside a rapid ascent of clinical landmarks – the first live birth in the United States from living-donor uterus transplantation in 2017 at Baylor University Medical Center in Houston,4 for instance, and the first live birth in the United States from deceased-donor uterus transplantation in 2019 at the Cleveland Clinic – there have been significant improvements in surgical retrieval of the uterus and in the optimization of graft performance.5

Most notably, the utero-ovarian vein has been used successfully in living donors to achieve venous drainage of the graft. This has lessened the risks of deep pelvic dissection in the living donor and made the transition to laparoscopic and robotic approaches in the living donor much easier.

Donor procurement, venous drainage

Adequate circulatory inflow and outflow for the transplanted uterus are essential both for the prevention of ischemia and thrombosis, which have been major causes of graft failure, and for meeting the increased demands of blood flow during pregnancy. Of the two, the outflow is the more challenging component.

Venous drainage traditionally has been accomplished through the use of the uterine veins, which drain into the internal iliac veins; often the vascular graft will include a portion of the internal iliac vessel which can be connected via anastomoses to the external iliac vein classically in deceased donors. Typically, the gynecologic surgeon on the team performs the vaginal anastomosis and suspension of the uterus, while the transplant surgeons perform the venous and arterial anastomoses.

In the living-donor model, procurement and dissection of these often unpredictable and tortuous complexes in the deep pelvis – particularly the branching uterine veins that lie in close proximity to the ureter, bladder, other blood vessels, and rectum – can be risky. The anatomic variants in the uterine vein are numerous, and even in one patient, a comprehensive dissection on one side cannot be expected to be mirrored on the contralateral side.

In addition to the risk of injury to the donor, the anastomosis may be unsuccessful as the veins are thinly walled and challenging to suture. As such, multiple modifications have been developed, often adapted to the donor’s anatomy and the caliber and accessibility of vessels. Preoperative vascular imaging with CT and/or MRI may help to identify suitable candidates and also may facilitate presurgical planning of which vessels may be selected for use.

Recently, surgeons performing living-donor transplantations have successfully used the more accessible and less risky ovarian and/or utero-ovarian veins for venous anastomosis. In 2019, for instance, a team in Pune, India, reported laparoscopically dissecting the donor ovarian veins and a portion of the internal iliac artery, and completing anastomosis with bilateral donor internal iliac arteries to recipient internal iliac arteries, and bilateral donor ovarian veins to recipient external iliac veins.6 It is significant that these smaller-caliber vessels were found to able to support the uterus through pregnancy.

We must be cautious, however, to avoid removing donors’ ovaries. Oophorectomy for women in their 40s can result in significant long-term medical sequelae. Surgeons at Baylor have achieved at least one live birth after harvesting the donor’s utero-ovarian veins while conserving the ovaries – a significant advancement for the living-donor model.4

There is tremendous interest in developing minimally invasive approaches to further reduce living-donor risk. The Swedish team has completed a series of eight robotic hysterectomies in living-donor uterus transplantations as part of a second trial. Addressing the reality of a learning curve, their study was designed around a step-wise approach, mastering initial steps first – e.g., dissections of the uterovaginal fossa, arteries, and ureters – and ultimately converting to laparotomy.7 In the United States, Baylor University has now completed at least five completely robotic living-donor hysterectomies with complete vaginal extraction.

Published data on robotic surgery suggests that surgical access and perioperative visualization of the vessels may be improved. And as minimally invasive approaches are adopted and improved, the length of donor surgery – 10-13 hours of operating room time in the original Swedish series – should diminish, as should the morbidity associated with laparotomy.

Surgical acquisition of a uterine graft from a deceased donor diminishes concerns for injury to nearby structures. Therefore, although it is a technically similar procedure, a deceased-donor model allows more flexibility with the length, caliber, and number of vessels that can be used for anastomosis. The internal iliac vessels and even portions of the external iliac vessels and ovarian vessels can be used to allow maximum flexibility.8

Surgical technique for uterus recipients

For the recipient surgery, entry is achieved via a midline, vertical laparotomy. The external iliac vessels are exposed, and the sites of vascular anastomoses are identified. The peritoneal reflection of the bladder is identified and dissected away to expose the anterior vagina, and the vagina is opened to a diameter that matches the donor, typically using a monopolar electrosurgical cutting instrument.

The vault of the donor vagina will be attached to the recipient’s existing vagina or vaginal pouch. It is important to identify recipient vaginal mucosa and incorporate it into the vaginal anastomosis to reduce the risk of vaginal stricture. We recommend that the vaginal mucosa be tagged with PDS II sutures or grasped with allis clamps to prevent retraction.

Surgical teams have taken multiple approaches to vaginal anastomosis. The Cleveland Clinic has used both a running suture as well as a horizontal mattress stitch for closure. For the latter, a 30-inch double-armed 2.0 Vicryl allows for complete suturing of the recipient vagina – with eight stitches placed circumferentially – before the uterus is placed. Both ends of the suture are passed intra-abdominal to intravaginal in the recipient.9

Once the donor uterus is suspended, attention focuses on vascular anastomosis, with bilateral end-to-side anastomosis between the donor anterior division of the internal iliac arteries and the external iliac vessels of the recipient, and with venous drainage commonly achieved through the uterine veins draining into the internal or external iliac vein of the recipient. As mentioned, recent cases involving living donors have also demonstrated success with the use of ovarian and/or utero-ovarian veins. Care should be taken to avoid having tension or twisting across the anastomosis.

After adequate graft perfusion is confirmed, with the uterus turning from a dusky color to a pink and well-perfused organ, the vaginal anastomosis is completed, with the arms of the double-armed suture passed through the donor vagina, from intravaginal to intra-abdominal. Tension should be evenly spread along the recipient and donor vagina in order to reduce the formation of granulation tissue and the severity of future vaginal stricturing.

For uterine fixation, polypropylene sutures are placed between the graft uterosacral ligaments and recipient uterine rudiments, and between the graft round ligaments and the recipient pelvic side wall at the level of the deep inguinal ring.

Current uterus transplantation protocols require removal of the uterus after one or two live births are achieved, so that recipients will not be exposed to long-term immunosuppression.

Complications and controversies

Postoperative vaginal strictures can make embryo transfer difficult and are a common complication in both living- and deceased-donor models. The Cleveland Clinic team has applied techniques from vaginal reconstructive surgery to try to reduce the occurrence of postoperative strictures – mainly increasing attention paid to anastomosis tissue–site preparation and closure of the anastomosis using a tension-free interrupted suture technique, as described above.9 The jury is out on whether such changes are sufficient, and a more complete understanding of the causes of vaginal stricture is needed.

Other perioperative complications include infection and graft thrombosis, both of which typically result in urgent graft hysterectomy. During pregnancy, one of our patients experienced abnormal placentation, though this was not thought to be related to uterus transplantation.5

The U.S. Uterus Transplant Consortium (USUTC) is a group of active programs that are sharing ideas and outcomes and advocating for continued research in this rapidly developing field. Uterine transplants require collaboration with transplant surgery, transplant medicine, infectious disease, gynecologic surgery, high-risk obstetrics, and other specialties. While significant progress has been made in a short period of time, uterine transplantation is still in its early stages, and transplants should be done in institutions that have the capacity for mentorship, bioethical oversight, and long-term follow-up of donors, recipients, and offspring.

The USUTC has recently proposed guidelines for nomenclature related to operative technique, vascular anatomy, and uterine transplantation outcomes.10 It proposes standardizing the names for the four veins originating from the uterus (to eliminate current inconsistency), which will be important as optimal strategies for vascular anastomoses are discussed and determined.

In addition, the consortium is creating a registry for the rigorous collection of data on procedures and outcomes (from menstruation and pregnancy through delivery, graft removal, and long-term follow-up). A registry has also been proposed by the International Society for Uterine Transplantation.

A major question remains in our field: Is the living-donor or deceased-donor uterus transplant the best approach? Knowledge of the quality of the uterus is greater preoperatively within a living-donor model, but no matter how minimally invasive the technique, the donor still assumes some risk of prolonged surgery and extensive pelvic dissection for a transplant that is not lifesaving.

On the other hand, deceased-donor transplants require additional layers of organization and coordination, and the availability of suitable deceased-donor uteri will likely not be sufficient to meet the current demand. Many of us in the field believe that the future of uterine transplantation will involve some combination of living- and deceased-donor transplants – similar to other solid organ transplant programs.

Dr. Flyckt and Dr. Richards reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 2/2/21: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Richards' name in the photo caption.

References

1. Lancet. 2015;14:385:607-16.

2. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(1):23-5.

3. Transplantation. 2020;104(7):1312-5.

4. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1270-4.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(2):143-51.

6. J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:628-35.

7. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(9):1222-9.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(1):183.

9. Fertil Steril. 2020 Jul 16. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.017

10 Am J Transplant. 2020;20(12):3319-25.

Since the first baby was born after a uterus transplantation in Sweden in 2014, uterus transplantation has been rapidly transitioning toward clinical reality.1 Several teams in the United States and multiple teams worldwide have performed the procedure, with the total number of worldwide surgeries performed nearing 100.

Uterus transplantation is the first and only true treatment for women with absolute uterine factor infertility – estimated to affect 1 in 500 women – and is filling an unmet need for this population of women. Women who have sought participation in uterus transplantation research have had complex and meaningful reasons and motivations for doing so.2 Combined with an accumulation of successful pregnancies, this makes continued research and technical improvement a worthy endeavor.

Most of the births thus far have occurred through the living-donor model; the initial Swedish trial involved nine women, seven of whom completed the procedure with viable transplants from living donors, and gave birth to eight healthy children. (Two required hysterectomy prior to attempted embryo transfer.3)

The Cleveland Clinic opted to build its first – and still ongoing – trial focusing on deceased-donor uterus transplants on the premise that such an approach obviates any risk to the donor and presents the fewest ethical challenges at the current time. Of eight uterus transplants performed thus far at the Cleveland Clinic, there have been three live births and two graft failures. As of early 2021, there was one ongoing pregnancy and two patients in preparation for embryo transfer.

Thus far, neither the living- nor deceased-donor model of uterus transplantation has been demonstrated to be superior. However, as data accrues from deceased donor studies, we will be able to more directly compare outcomes.

In the meantime, alongside a rapid ascent of clinical landmarks – the first live birth in the United States from living-donor uterus transplantation in 2017 at Baylor University Medical Center in Houston,4 for instance, and the first live birth in the United States from deceased-donor uterus transplantation in 2019 at the Cleveland Clinic – there have been significant improvements in surgical retrieval of the uterus and in the optimization of graft performance.5

Most notably, the utero-ovarian vein has been used successfully in living donors to achieve venous drainage of the graft. This has lessened the risks of deep pelvic dissection in the living donor and made the transition to laparoscopic and robotic approaches in the living donor much easier.

Donor procurement, venous drainage

Adequate circulatory inflow and outflow for the transplanted uterus are essential both for the prevention of ischemia and thrombosis, which have been major causes of graft failure, and for meeting the increased demands of blood flow during pregnancy. Of the two, the outflow is the more challenging component.

Venous drainage traditionally has been accomplished through the use of the uterine veins, which drain into the internal iliac veins; often the vascular graft will include a portion of the internal iliac vessel which can be connected via anastomoses to the external iliac vein classically in deceased donors. Typically, the gynecologic surgeon on the team performs the vaginal anastomosis and suspension of the uterus, while the transplant surgeons perform the venous and arterial anastomoses.

In the living-donor model, procurement and dissection of these often unpredictable and tortuous complexes in the deep pelvis – particularly the branching uterine veins that lie in close proximity to the ureter, bladder, other blood vessels, and rectum – can be risky. The anatomic variants in the uterine vein are numerous, and even in one patient, a comprehensive dissection on one side cannot be expected to be mirrored on the contralateral side.

In addition to the risk of injury to the donor, the anastomosis may be unsuccessful as the veins are thinly walled and challenging to suture. As such, multiple modifications have been developed, often adapted to the donor’s anatomy and the caliber and accessibility of vessels. Preoperative vascular imaging with CT and/or MRI may help to identify suitable candidates and also may facilitate presurgical planning of which vessels may be selected for use.

Recently, surgeons performing living-donor transplantations have successfully used the more accessible and less risky ovarian and/or utero-ovarian veins for venous anastomosis. In 2019, for instance, a team in Pune, India, reported laparoscopically dissecting the donor ovarian veins and a portion of the internal iliac artery, and completing anastomosis with bilateral donor internal iliac arteries to recipient internal iliac arteries, and bilateral donor ovarian veins to recipient external iliac veins.6 It is significant that these smaller-caliber vessels were found to able to support the uterus through pregnancy.

We must be cautious, however, to avoid removing donors’ ovaries. Oophorectomy for women in their 40s can result in significant long-term medical sequelae. Surgeons at Baylor have achieved at least one live birth after harvesting the donor’s utero-ovarian veins while conserving the ovaries – a significant advancement for the living-donor model.4

There is tremendous interest in developing minimally invasive approaches to further reduce living-donor risk. The Swedish team has completed a series of eight robotic hysterectomies in living-donor uterus transplantations as part of a second trial. Addressing the reality of a learning curve, their study was designed around a step-wise approach, mastering initial steps first – e.g., dissections of the uterovaginal fossa, arteries, and ureters – and ultimately converting to laparotomy.7 In the United States, Baylor University has now completed at least five completely robotic living-donor hysterectomies with complete vaginal extraction.

Published data on robotic surgery suggests that surgical access and perioperative visualization of the vessels may be improved. And as minimally invasive approaches are adopted and improved, the length of donor surgery – 10-13 hours of operating room time in the original Swedish series – should diminish, as should the morbidity associated with laparotomy.

Surgical acquisition of a uterine graft from a deceased donor diminishes concerns for injury to nearby structures. Therefore, although it is a technically similar procedure, a deceased-donor model allows more flexibility with the length, caliber, and number of vessels that can be used for anastomosis. The internal iliac vessels and even portions of the external iliac vessels and ovarian vessels can be used to allow maximum flexibility.8

Surgical technique for uterus recipients

For the recipient surgery, entry is achieved via a midline, vertical laparotomy. The external iliac vessels are exposed, and the sites of vascular anastomoses are identified. The peritoneal reflection of the bladder is identified and dissected away to expose the anterior vagina, and the vagina is opened to a diameter that matches the donor, typically using a monopolar electrosurgical cutting instrument.

The vault of the donor vagina will be attached to the recipient’s existing vagina or vaginal pouch. It is important to identify recipient vaginal mucosa and incorporate it into the vaginal anastomosis to reduce the risk of vaginal stricture. We recommend that the vaginal mucosa be tagged with PDS II sutures or grasped with allis clamps to prevent retraction.

Surgical teams have taken multiple approaches to vaginal anastomosis. The Cleveland Clinic has used both a running suture as well as a horizontal mattress stitch for closure. For the latter, a 30-inch double-armed 2.0 Vicryl allows for complete suturing of the recipient vagina – with eight stitches placed circumferentially – before the uterus is placed. Both ends of the suture are passed intra-abdominal to intravaginal in the recipient.9

Once the donor uterus is suspended, attention focuses on vascular anastomosis, with bilateral end-to-side anastomosis between the donor anterior division of the internal iliac arteries and the external iliac vessels of the recipient, and with venous drainage commonly achieved through the uterine veins draining into the internal or external iliac vein of the recipient. As mentioned, recent cases involving living donors have also demonstrated success with the use of ovarian and/or utero-ovarian veins. Care should be taken to avoid having tension or twisting across the anastomosis.

After adequate graft perfusion is confirmed, with the uterus turning from a dusky color to a pink and well-perfused organ, the vaginal anastomosis is completed, with the arms of the double-armed suture passed through the donor vagina, from intravaginal to intra-abdominal. Tension should be evenly spread along the recipient and donor vagina in order to reduce the formation of granulation tissue and the severity of future vaginal stricturing.

For uterine fixation, polypropylene sutures are placed between the graft uterosacral ligaments and recipient uterine rudiments, and between the graft round ligaments and the recipient pelvic side wall at the level of the deep inguinal ring.

Current uterus transplantation protocols require removal of the uterus after one or two live births are achieved, so that recipients will not be exposed to long-term immunosuppression.

Complications and controversies

Postoperative vaginal strictures can make embryo transfer difficult and are a common complication in both living- and deceased-donor models. The Cleveland Clinic team has applied techniques from vaginal reconstructive surgery to try to reduce the occurrence of postoperative strictures – mainly increasing attention paid to anastomosis tissue–site preparation and closure of the anastomosis using a tension-free interrupted suture technique, as described above.9 The jury is out on whether such changes are sufficient, and a more complete understanding of the causes of vaginal stricture is needed.

Other perioperative complications include infection and graft thrombosis, both of which typically result in urgent graft hysterectomy. During pregnancy, one of our patients experienced abnormal placentation, though this was not thought to be related to uterus transplantation.5

The U.S. Uterus Transplant Consortium (USUTC) is a group of active programs that are sharing ideas and outcomes and advocating for continued research in this rapidly developing field. Uterine transplants require collaboration with transplant surgery, transplant medicine, infectious disease, gynecologic surgery, high-risk obstetrics, and other specialties. While significant progress has been made in a short period of time, uterine transplantation is still in its early stages, and transplants should be done in institutions that have the capacity for mentorship, bioethical oversight, and long-term follow-up of donors, recipients, and offspring.

The USUTC has recently proposed guidelines for nomenclature related to operative technique, vascular anatomy, and uterine transplantation outcomes.10 It proposes standardizing the names for the four veins originating from the uterus (to eliminate current inconsistency), which will be important as optimal strategies for vascular anastomoses are discussed and determined.

In addition, the consortium is creating a registry for the rigorous collection of data on procedures and outcomes (from menstruation and pregnancy through delivery, graft removal, and long-term follow-up). A registry has also been proposed by the International Society for Uterine Transplantation.

A major question remains in our field: Is the living-donor or deceased-donor uterus transplant the best approach? Knowledge of the quality of the uterus is greater preoperatively within a living-donor model, but no matter how minimally invasive the technique, the donor still assumes some risk of prolonged surgery and extensive pelvic dissection for a transplant that is not lifesaving.

On the other hand, deceased-donor transplants require additional layers of organization and coordination, and the availability of suitable deceased-donor uteri will likely not be sufficient to meet the current demand. Many of us in the field believe that the future of uterine transplantation will involve some combination of living- and deceased-donor transplants – similar to other solid organ transplant programs.

Dr. Flyckt and Dr. Richards reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Correction, 2/2/21: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Richards' name in the photo caption.

References

1. Lancet. 2015;14:385:607-16.

2. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(1):23-5.

3. Transplantation. 2020;104(7):1312-5.

4. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1270-4.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(2):143-51.

6. J Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:628-35.

7. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(9):1222-9.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(1):183.

9. Fertil Steril. 2020 Jul 16. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.017

10 Am J Transplant. 2020;20(12):3319-25.