User login

The authors would like to acknowledge Tony Quang, MD, JD, for the advice given on this project.

Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases is typically delivered either as a short course of 1 to 5 fractions or protracted over longer courses of up to 20 treatments. These longer courses can be burdensome and discourage its utilization, despite a 50% to 80% likelihood of meaningful pain relief from only a single fraction of radiation therapy. Meanwhile, there are multiple randomized studies that have demonstrated that shorter course(s) are equivalent for pain control.

Although the VHA currently has 143 medical facilities that have cancer diagnostic and treatment capabilities, only 40 have radiation oncology services on-site.1 Thus, access to palliative radiotherapy may be limited for veterans who do not live close by, and many may seek care outside the VHA. At VHA radiation oncology centers, single-fraction radiation therapy (SFRT) is routinely offered by the majority of radiation oncologists.2,3 However, the longer course is commonly preferred outside the VA, and a recent SEER-Medicare analysis of more than 3,000 patients demonstrated that the majority of patients treated outside the VA actually receive more than 10 treatments.4 For this reason, the VA National Palliative Radiotherapy Task Force prepared this document to provide guidance for clinicians within and outside the VA to increase awareness of the appropriateness, effectiveness, and convenience of SFRT as opposed to longer courses of treatment that increase the burden of care at the end of life and often are unnecessary.

Veterans, Cancer, and Metastases

Within the VA, an estimated 40,000 new cancer cases are diagnosed each year, and 175,000 veterans undergo cancer care within the VHA annually.1 Unfortunately, the majority will develop bone metastases with postmortem examinations, suggesting that the rate can be as high as 90% at the end of life.5-7 For many, including veterans with cancer, pain control can be difficult, and access to palliative radiotherapy is critical.8

Single-Fraction Palliatiev Radiation Therapy

Historically, patients with painful bone metastases have been treated with courses of palliative radiotherapy ranging between 2 and 4 weeks of daily treatments. However, several large randomized clinical trials comparing a single treatment with multiple treatments have established that SFRT provides equivalent rates of pain relief even when it may be required for a second time.9-12 Recommendations based on these trials have been incorporated into various treatment guidelines that widely acknowledge the efficacy of SFRT.13-15

For this reason, SFRT is often preferred at many centers because it is substantially more convenient for patients with cancer. It reduces travel time for daily radiation clinic visits, which allows for more time with loved ones outside the medical establishment. Furthermore, SFRT improves patient access to radiotherapy and reduces costs. The benefits can be direct as well as indirect to those who have to take time for numerous visits.

Longer courses of palliative radiotherapy can be burdensome for patients and primary care providers. Unnecessarily protracted courses of palliative radiotherapy also delay the receipt of systemic therapies because they are typically considered unsafe to administer concurrently. Moreover, when SFRT is unavailable, the burden of long-course palliation is known to discourage health care providers from referring patients since opioid therapy is more convenient, even though it exchanges lucidity for analgesia.16,17

For this reason, the authors believe that it is in the best interest for veterans with terminal cancers and their providers to be aware of the shorter SFRT for effective, convenient pain relief. This treatment option is particularly relevant for patients with a poor performance status, patients already in hospice care, or patient who travel long distances.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701.

2. Moghanaki D, Cheuk AV, Fosmire H, et al; U.S. Veterans Healthcare Administration National Palliative Radiotherapy Taskforce. Availability of single fraction palliative radiotherapy for cancer patients receiving end-of-life care within the Veterans Healthcare Administration. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1221-1225.

3. Dawson GA, Glushko I, Hagan MP. A cross-sectional view of radiation dose fractionation schemes used for painful bone metastases cases within Veterans Health Administration Radiation Oncology Centers. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29 suppl):abstract 177.

4. Bekelman JE, Epstein AJ, Emanuel EJ. Single- vs multiple-fraction radiotherapy for bone metastases from prostate cancer. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1501-1502.

5. Galasko CSB. The anatomy and pathways of skeletal metastases. In: Weiss L, Gilbert AH, eds. Bone Metastasis. Boston, MA: GK Hall; 1981:49-63.

6. Bubendorf L, Schöpfer A, Wagner U, et al. Metastatic patterns in prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(5):578-583.

7. Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20, pt 2):6243s-6249s.

8. Geriatrics and Extended Care Strategic Healthcare Group, National Pain Management Coordinating Committee, Veterans Health Administration. Pain as the 5th Vital Sign Toolkit. Rev. ed. Washington, DC: National Pain Management Coordinating Committee; 2000.

9. Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(11):798-804.

10. Chow E, Hoskins PJ, Wu J, et al. A phase III international randomised trial comparing single with multiple fractions for re-irradiation of painful bone metastases: National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCTC CTG) SC 20. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18(2):125-128.

11. Fairchild A, Barnes E, Ghosh S, et al. International patterns of practice in palliative radiotherapy for painful bone metastases: evidence-based practice? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(5):1501-1510.

12. Chow E, van der Linden YM, Roos D, et al. Single fraction versus multiple fractions of repeat radiation for painful bone metastases: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):164-171.

13. Lutz ST, Berk L, Chang E, et al; American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an ASTRO evidencebased guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol, Biol, Phys. 2011;79(4):965-976.

14. Expert Panel on Radiation Oncology-Bone Metastases, Lo SS, Lutz ST, Chang EL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® spinal bone metastases. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(1):9-19.

15. Expert Panel on Radiation Oncology-Bone Metastases, Lutz ST, Lo SS, Chang EL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® non-spinal bone metastases. J Palliative Med. 2012;15(5):521-526.

16. Guadagnolo BA, Liao KP, Elting L, Giordano S, Buchholz TA, Shih YC. Use of radiation therapy in the last 30 days of life among a large population-based cohort of elderly patients in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):80-87.

17. Schuster J, Han T, Anscher M, Moghanaki D. Hospice providers awareness of the benefits and availability of single-fraction palliative radiotherapy. J Hospice Palliat Care Nurs. 2014;16(2):67-72.

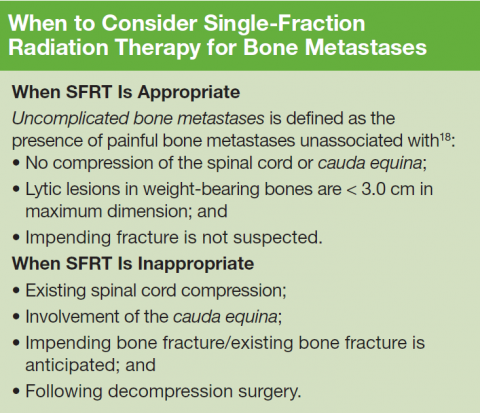

18. Cheon PM, Wong E, Thavarajah N, et al. A definition of “uncomplicated bone metastases” based on previous bone metastases trials comparing single-fraction and multi-fraction radiation therapy. J Bone Oncol. 2015;4(1):13-17.

The authors would like to acknowledge Tony Quang, MD, JD, for the advice given on this project.

Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases is typically delivered either as a short course of 1 to 5 fractions or protracted over longer courses of up to 20 treatments. These longer courses can be burdensome and discourage its utilization, despite a 50% to 80% likelihood of meaningful pain relief from only a single fraction of radiation therapy. Meanwhile, there are multiple randomized studies that have demonstrated that shorter course(s) are equivalent for pain control.

Although the VHA currently has 143 medical facilities that have cancer diagnostic and treatment capabilities, only 40 have radiation oncology services on-site.1 Thus, access to palliative radiotherapy may be limited for veterans who do not live close by, and many may seek care outside the VHA. At VHA radiation oncology centers, single-fraction radiation therapy (SFRT) is routinely offered by the majority of radiation oncologists.2,3 However, the longer course is commonly preferred outside the VA, and a recent SEER-Medicare analysis of more than 3,000 patients demonstrated that the majority of patients treated outside the VA actually receive more than 10 treatments.4 For this reason, the VA National Palliative Radiotherapy Task Force prepared this document to provide guidance for clinicians within and outside the VA to increase awareness of the appropriateness, effectiveness, and convenience of SFRT as opposed to longer courses of treatment that increase the burden of care at the end of life and often are unnecessary.

Veterans, Cancer, and Metastases

Within the VA, an estimated 40,000 new cancer cases are diagnosed each year, and 175,000 veterans undergo cancer care within the VHA annually.1 Unfortunately, the majority will develop bone metastases with postmortem examinations, suggesting that the rate can be as high as 90% at the end of life.5-7 For many, including veterans with cancer, pain control can be difficult, and access to palliative radiotherapy is critical.8

Single-Fraction Palliatiev Radiation Therapy

Historically, patients with painful bone metastases have been treated with courses of palliative radiotherapy ranging between 2 and 4 weeks of daily treatments. However, several large randomized clinical trials comparing a single treatment with multiple treatments have established that SFRT provides equivalent rates of pain relief even when it may be required for a second time.9-12 Recommendations based on these trials have been incorporated into various treatment guidelines that widely acknowledge the efficacy of SFRT.13-15

For this reason, SFRT is often preferred at many centers because it is substantially more convenient for patients with cancer. It reduces travel time for daily radiation clinic visits, which allows for more time with loved ones outside the medical establishment. Furthermore, SFRT improves patient access to radiotherapy and reduces costs. The benefits can be direct as well as indirect to those who have to take time for numerous visits.

Longer courses of palliative radiotherapy can be burdensome for patients and primary care providers. Unnecessarily protracted courses of palliative radiotherapy also delay the receipt of systemic therapies because they are typically considered unsafe to administer concurrently. Moreover, when SFRT is unavailable, the burden of long-course palliation is known to discourage health care providers from referring patients since opioid therapy is more convenient, even though it exchanges lucidity for analgesia.16,17

For this reason, the authors believe that it is in the best interest for veterans with terminal cancers and their providers to be aware of the shorter SFRT for effective, convenient pain relief. This treatment option is particularly relevant for patients with a poor performance status, patients already in hospice care, or patient who travel long distances.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

The authors would like to acknowledge Tony Quang, MD, JD, for the advice given on this project.

Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases is typically delivered either as a short course of 1 to 5 fractions or protracted over longer courses of up to 20 treatments. These longer courses can be burdensome and discourage its utilization, despite a 50% to 80% likelihood of meaningful pain relief from only a single fraction of radiation therapy. Meanwhile, there are multiple randomized studies that have demonstrated that shorter course(s) are equivalent for pain control.

Although the VHA currently has 143 medical facilities that have cancer diagnostic and treatment capabilities, only 40 have radiation oncology services on-site.1 Thus, access to palliative radiotherapy may be limited for veterans who do not live close by, and many may seek care outside the VHA. At VHA radiation oncology centers, single-fraction radiation therapy (SFRT) is routinely offered by the majority of radiation oncologists.2,3 However, the longer course is commonly preferred outside the VA, and a recent SEER-Medicare analysis of more than 3,000 patients demonstrated that the majority of patients treated outside the VA actually receive more than 10 treatments.4 For this reason, the VA National Palliative Radiotherapy Task Force prepared this document to provide guidance for clinicians within and outside the VA to increase awareness of the appropriateness, effectiveness, and convenience of SFRT as opposed to longer courses of treatment that increase the burden of care at the end of life and often are unnecessary.

Veterans, Cancer, and Metastases

Within the VA, an estimated 40,000 new cancer cases are diagnosed each year, and 175,000 veterans undergo cancer care within the VHA annually.1 Unfortunately, the majority will develop bone metastases with postmortem examinations, suggesting that the rate can be as high as 90% at the end of life.5-7 For many, including veterans with cancer, pain control can be difficult, and access to palliative radiotherapy is critical.8

Single-Fraction Palliatiev Radiation Therapy

Historically, patients with painful bone metastases have been treated with courses of palliative radiotherapy ranging between 2 and 4 weeks of daily treatments. However, several large randomized clinical trials comparing a single treatment with multiple treatments have established that SFRT provides equivalent rates of pain relief even when it may be required for a second time.9-12 Recommendations based on these trials have been incorporated into various treatment guidelines that widely acknowledge the efficacy of SFRT.13-15

For this reason, SFRT is often preferred at many centers because it is substantially more convenient for patients with cancer. It reduces travel time for daily radiation clinic visits, which allows for more time with loved ones outside the medical establishment. Furthermore, SFRT improves patient access to radiotherapy and reduces costs. The benefits can be direct as well as indirect to those who have to take time for numerous visits.

Longer courses of palliative radiotherapy can be burdensome for patients and primary care providers. Unnecessarily protracted courses of palliative radiotherapy also delay the receipt of systemic therapies because they are typically considered unsafe to administer concurrently. Moreover, when SFRT is unavailable, the burden of long-course palliation is known to discourage health care providers from referring patients since opioid therapy is more convenient, even though it exchanges lucidity for analgesia.16,17

For this reason, the authors believe that it is in the best interest for veterans with terminal cancers and their providers to be aware of the shorter SFRT for effective, convenient pain relief. This treatment option is particularly relevant for patients with a poor performance status, patients already in hospice care, or patient who travel long distances.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701.

2. Moghanaki D, Cheuk AV, Fosmire H, et al; U.S. Veterans Healthcare Administration National Palliative Radiotherapy Taskforce. Availability of single fraction palliative radiotherapy for cancer patients receiving end-of-life care within the Veterans Healthcare Administration. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1221-1225.

3. Dawson GA, Glushko I, Hagan MP. A cross-sectional view of radiation dose fractionation schemes used for painful bone metastases cases within Veterans Health Administration Radiation Oncology Centers. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29 suppl):abstract 177.

4. Bekelman JE, Epstein AJ, Emanuel EJ. Single- vs multiple-fraction radiotherapy for bone metastases from prostate cancer. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1501-1502.

5. Galasko CSB. The anatomy and pathways of skeletal metastases. In: Weiss L, Gilbert AH, eds. Bone Metastasis. Boston, MA: GK Hall; 1981:49-63.

6. Bubendorf L, Schöpfer A, Wagner U, et al. Metastatic patterns in prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(5):578-583.

7. Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20, pt 2):6243s-6249s.

8. Geriatrics and Extended Care Strategic Healthcare Group, National Pain Management Coordinating Committee, Veterans Health Administration. Pain as the 5th Vital Sign Toolkit. Rev. ed. Washington, DC: National Pain Management Coordinating Committee; 2000.

9. Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(11):798-804.

10. Chow E, Hoskins PJ, Wu J, et al. A phase III international randomised trial comparing single with multiple fractions for re-irradiation of painful bone metastases: National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCTC CTG) SC 20. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18(2):125-128.

11. Fairchild A, Barnes E, Ghosh S, et al. International patterns of practice in palliative radiotherapy for painful bone metastases: evidence-based practice? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(5):1501-1510.

12. Chow E, van der Linden YM, Roos D, et al. Single fraction versus multiple fractions of repeat radiation for painful bone metastases: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):164-171.

13. Lutz ST, Berk L, Chang E, et al; American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an ASTRO evidencebased guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol, Biol, Phys. 2011;79(4):965-976.

14. Expert Panel on Radiation Oncology-Bone Metastases, Lo SS, Lutz ST, Chang EL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® spinal bone metastases. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(1):9-19.

15. Expert Panel on Radiation Oncology-Bone Metastases, Lutz ST, Lo SS, Chang EL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® non-spinal bone metastases. J Palliative Med. 2012;15(5):521-526.

16. Guadagnolo BA, Liao KP, Elting L, Giordano S, Buchholz TA, Shih YC. Use of radiation therapy in the last 30 days of life among a large population-based cohort of elderly patients in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):80-87.

17. Schuster J, Han T, Anscher M, Moghanaki D. Hospice providers awareness of the benefits and availability of single-fraction palliative radiotherapy. J Hospice Palliat Care Nurs. 2014;16(2):67-72.

18. Cheon PM, Wong E, Thavarajah N, et al. A definition of “uncomplicated bone metastases” based on previous bone metastases trials comparing single-fraction and multi-fraction radiation therapy. J Bone Oncol. 2015;4(1):13-17.

1. Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Dorn RA, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Mil Med. 2012;177(6):693-701.

2. Moghanaki D, Cheuk AV, Fosmire H, et al; U.S. Veterans Healthcare Administration National Palliative Radiotherapy Taskforce. Availability of single fraction palliative radiotherapy for cancer patients receiving end-of-life care within the Veterans Healthcare Administration. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(11):1221-1225.

3. Dawson GA, Glushko I, Hagan MP. A cross-sectional view of radiation dose fractionation schemes used for painful bone metastases cases within Veterans Health Administration Radiation Oncology Centers. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29 suppl):abstract 177.

4. Bekelman JE, Epstein AJ, Emanuel EJ. Single- vs multiple-fraction radiotherapy for bone metastases from prostate cancer. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1501-1502.

5. Galasko CSB. The anatomy and pathways of skeletal metastases. In: Weiss L, Gilbert AH, eds. Bone Metastasis. Boston, MA: GK Hall; 1981:49-63.

6. Bubendorf L, Schöpfer A, Wagner U, et al. Metastatic patterns in prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(5):578-583.

7. Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20, pt 2):6243s-6249s.

8. Geriatrics and Extended Care Strategic Healthcare Group, National Pain Management Coordinating Committee, Veterans Health Administration. Pain as the 5th Vital Sign Toolkit. Rev. ed. Washington, DC: National Pain Management Coordinating Committee; 2000.

9. Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, et al. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(11):798-804.

10. Chow E, Hoskins PJ, Wu J, et al. A phase III international randomised trial comparing single with multiple fractions for re-irradiation of painful bone metastases: National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCTC CTG) SC 20. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18(2):125-128.

11. Fairchild A, Barnes E, Ghosh S, et al. International patterns of practice in palliative radiotherapy for painful bone metastases: evidence-based practice? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(5):1501-1510.

12. Chow E, van der Linden YM, Roos D, et al. Single fraction versus multiple fractions of repeat radiation for painful bone metastases: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):164-171.

13. Lutz ST, Berk L, Chang E, et al; American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: an ASTRO evidencebased guideline. Int J Radiat Oncol, Biol, Phys. 2011;79(4):965-976.

14. Expert Panel on Radiation Oncology-Bone Metastases, Lo SS, Lutz ST, Chang EL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® spinal bone metastases. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(1):9-19.

15. Expert Panel on Radiation Oncology-Bone Metastases, Lutz ST, Lo SS, Chang EL, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® non-spinal bone metastases. J Palliative Med. 2012;15(5):521-526.

16. Guadagnolo BA, Liao KP, Elting L, Giordano S, Buchholz TA, Shih YC. Use of radiation therapy in the last 30 days of life among a large population-based cohort of elderly patients in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):80-87.

17. Schuster J, Han T, Anscher M, Moghanaki D. Hospice providers awareness of the benefits and availability of single-fraction palliative radiotherapy. J Hospice Palliat Care Nurs. 2014;16(2):67-72.

18. Cheon PM, Wong E, Thavarajah N, et al. A definition of “uncomplicated bone metastases” based on previous bone metastases trials comparing single-fraction and multi-fraction radiation therapy. J Bone Oncol. 2015;4(1):13-17.