User login

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Diagnosing chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) remains a challenge in 2018, according to a presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Even with updated World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, karyotyping, and genetic analyses, it can be difficult to distinguish CMML from other conditions, according to Nadira Duraković, MD, PhD, of the University Hospital Zagreb in Croatia.

However, Dr. Duraković said there are characteristics that differentiate CMML from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), and atypical chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Furthermore, studies have suggested that monocyte subset distribution analysis can be useful for diagnosing CMML.

Dr. Duraković began her presentation with an overview of the 2016 WHO classification of CMML (Blood 2016 127:2391-2405).

According to the WHO, patients have CMML if:

- They have persistent peripheral blood monocytosis (1×109/L) with monocytes accounting for 10% of the white blood cell count

- They do not meet WHO criteria for BCR-ABL1-positive CML, primary myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, or essential thrombocythemia

- There is no evidence of PCM1-JAK2 or PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1 rearrangement

- They have fewer than 20% blasts in the blood and bone marrow

- They have dysplasia in one or more myeloid lineages

- If myelodysplasia is absent or minimal, an acquired clonal cytogenetic or molecular genetic abnormality must be present.

Alternatively, if patients have monocytosis that has persisted for at least 3 months, and all other causes of monocytosis have been excluded, “you can say that your patient has CMML,” Dr. Duraković said.

Other causes of monocytosis include infections, malignancies, medications, inflammatory conditions, and other conditions such as pregnancy.

However, Dr. Duraković pointed out that the cause of monocytosis cannot always be determined, and, in some cases, CMML patients may not meet the WHO criteria.

“[T]here are cases where there just aren’t enough monocytes to fulfill the WHO criteria,” Dr. Duraković said. “You can have a patient with peripheral blood cytopenia and monocytosis who does not have 1,000 monocytes. Patients can have progressive dysplasia, can have splenomegaly, be really sick, but fail to meet WHO criteria.”

Distinguishing CMML from other conditions

“Differentiating CMML from myelodysplastic syndromes can be tough,” Dr. Duraković said. “There are dysplastic features that are present in CMML . . . but, in CMML, they are more subtle, and they are more difficult to appreciate than in myelodysplastic syndromes.”

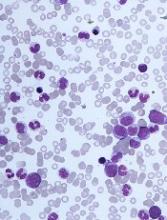

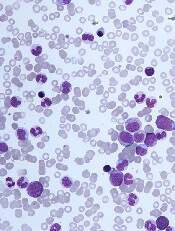

The ratio of myeloid to erythroid cells is elevated in CMML, and patients may have atypical monocytes (paramyeloid cells) that are unique to CMML.

Dr. Duraković noted that megakaryocyte dysplasia in CMML can be characterized by “myeloproliferative megakaryocytes,” which are large cells that cluster and have hyperlobulated nuclei, or “MDS megakaryocytes,” which are small, solitary cells with hypolobulated nuclei.

She went on to explain that “MPN phenotype” CMML is characterized by leukocytosis, monocytosis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and clinical features of myeloproliferation (fatigue, night sweats, bone pain, weight loss, etc.).

Thirty percent of cases are associated with splenomegaly, and 30% of patients can have an increase in bone marrow reticulin fibrosis.

Dr. Duraković also noted that a prior MPN diagnosis excludes CMML. The presence of common MPN mutations, such as JAK2, CALR, or MPL, suggests a patient has an MPN with monocytosis rather than CMML.

Patients who have unclassified MPNs or MDS, rather than CMML, either do not have 1,000 monocytes or the monocytes do not represent more than 10% of the differential, Dr. Duraković said.

She also noted that it can be difficult to differentiate CMML from atypical CML.

“Atypical CML is characterized by profound dysgranulopoiesis, absence of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, and neutrophilia,” Dr. Duraković explained. “Those patients [commonly] have monocytosis, but, here, that 10% rule is valuable because their monocytes comprise less than 10% of the entire white blood cell count.”

Karyotyping, genotyping, and immunophenotyping

“There is no disease-defining karyotype abnormality [in CMML],” Dr. Duraković noted.

She said 30% of patients have abnormal karyotype, and the most common abnormality is trisomy 8. Unlike in patients with MDS, del(5q) and monosomal karyotypes are infrequent in patients with CMML.

Similarly, there are no “disease-defining” mutations or genetic changes in CMML, although CMML is genetically distinct from MDS, Dr. Duraković said.

For instance, SRSF2 encodes a component of the spliceosome that is mutated in almost half of CMML patients and less than 10% of MDS patients. Likewise, ASLX1 and TET2 are “much more frequently involved” in CMML than in MDS, Dr. Duraković said.

In a 2012 study of 275 CMML patients, researchers found that 93% of patients had at least one somatic mutation in nine recurrently mutated genes—SRFS2, ASXL1, CBL, EZH2, JAK2V617F, KRAS, NRAS, RUNX1, and TET2 (Blood 2012 120:3080-3088).

However, Dr. Duraković noted that these mutations are found in other disorders as well, so this information may not be helpful in differentiating CMML from other disorders.

A 2015 study revealed a technique that does appear useful for identifying CMML—monocyte subset distribution analysis (Blood 2015 125(23): 3618–3626).

For this analysis, monocytes are divided into the following categories:

- Classical/MO1 (CD14bright/CD16−)

- Intermediate/MO2 (CD14bright/CD16+)

- Non-classical/MO3 (CD14dim/CD16+).

The researchers found that CMML patients had an increase in the fraction of classical monocytes (with a cutoff value of 94.0%), as compared to healthy control subjects, patients with another hematologic disorder, and patients with reactive monocytosis.

A 2018 study confirmed that monocyte subset distribution analysis could differentiate CMML from other hematologic disorders, with the exception of atypical CML (Am J Clin Pathol 2018 150(4):293-302).

This study also suggested that a decreased percentage of non-classical monocytes was more sensitive than an increased percentage of classical monocytes.

Despite the differences between these studies, “monocyte subset distribution analysis is showing promise as a method of identifying hard-to-identify CMML patients with ease and affordability,” Dr. Duraković said.

She added that the technique can be implemented in clinical practice using the HematoflowTM solution (Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2018 94(5):658-661).

Dr. Duraković did not report any conflicts of interest.

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Diagnosing chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) remains a challenge in 2018, according to a presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Even with updated World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, karyotyping, and genetic analyses, it can be difficult to distinguish CMML from other conditions, according to Nadira Duraković, MD, PhD, of the University Hospital Zagreb in Croatia.

However, Dr. Duraković said there are characteristics that differentiate CMML from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), and atypical chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Furthermore, studies have suggested that monocyte subset distribution analysis can be useful for diagnosing CMML.

Dr. Duraković began her presentation with an overview of the 2016 WHO classification of CMML (Blood 2016 127:2391-2405).

According to the WHO, patients have CMML if:

- They have persistent peripheral blood monocytosis (1×109/L) with monocytes accounting for 10% of the white blood cell count

- They do not meet WHO criteria for BCR-ABL1-positive CML, primary myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, or essential thrombocythemia

- There is no evidence of PCM1-JAK2 or PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1 rearrangement

- They have fewer than 20% blasts in the blood and bone marrow

- They have dysplasia in one or more myeloid lineages

- If myelodysplasia is absent or minimal, an acquired clonal cytogenetic or molecular genetic abnormality must be present.

Alternatively, if patients have monocytosis that has persisted for at least 3 months, and all other causes of monocytosis have been excluded, “you can say that your patient has CMML,” Dr. Duraković said.

Other causes of monocytosis include infections, malignancies, medications, inflammatory conditions, and other conditions such as pregnancy.

However, Dr. Duraković pointed out that the cause of monocytosis cannot always be determined, and, in some cases, CMML patients may not meet the WHO criteria.

“[T]here are cases where there just aren’t enough monocytes to fulfill the WHO criteria,” Dr. Duraković said. “You can have a patient with peripheral blood cytopenia and monocytosis who does not have 1,000 monocytes. Patients can have progressive dysplasia, can have splenomegaly, be really sick, but fail to meet WHO criteria.”

Distinguishing CMML from other conditions

“Differentiating CMML from myelodysplastic syndromes can be tough,” Dr. Duraković said. “There are dysplastic features that are present in CMML . . . but, in CMML, they are more subtle, and they are more difficult to appreciate than in myelodysplastic syndromes.”

The ratio of myeloid to erythroid cells is elevated in CMML, and patients may have atypical monocytes (paramyeloid cells) that are unique to CMML.

Dr. Duraković noted that megakaryocyte dysplasia in CMML can be characterized by “myeloproliferative megakaryocytes,” which are large cells that cluster and have hyperlobulated nuclei, or “MDS megakaryocytes,” which are small, solitary cells with hypolobulated nuclei.

She went on to explain that “MPN phenotype” CMML is characterized by leukocytosis, monocytosis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and clinical features of myeloproliferation (fatigue, night sweats, bone pain, weight loss, etc.).

Thirty percent of cases are associated with splenomegaly, and 30% of patients can have an increase in bone marrow reticulin fibrosis.

Dr. Duraković also noted that a prior MPN diagnosis excludes CMML. The presence of common MPN mutations, such as JAK2, CALR, or MPL, suggests a patient has an MPN with monocytosis rather than CMML.

Patients who have unclassified MPNs or MDS, rather than CMML, either do not have 1,000 monocytes or the monocytes do not represent more than 10% of the differential, Dr. Duraković said.

She also noted that it can be difficult to differentiate CMML from atypical CML.

“Atypical CML is characterized by profound dysgranulopoiesis, absence of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, and neutrophilia,” Dr. Duraković explained. “Those patients [commonly] have monocytosis, but, here, that 10% rule is valuable because their monocytes comprise less than 10% of the entire white blood cell count.”

Karyotyping, genotyping, and immunophenotyping

“There is no disease-defining karyotype abnormality [in CMML],” Dr. Duraković noted.

She said 30% of patients have abnormal karyotype, and the most common abnormality is trisomy 8. Unlike in patients with MDS, del(5q) and monosomal karyotypes are infrequent in patients with CMML.

Similarly, there are no “disease-defining” mutations or genetic changes in CMML, although CMML is genetically distinct from MDS, Dr. Duraković said.

For instance, SRSF2 encodes a component of the spliceosome that is mutated in almost half of CMML patients and less than 10% of MDS patients. Likewise, ASLX1 and TET2 are “much more frequently involved” in CMML than in MDS, Dr. Duraković said.

In a 2012 study of 275 CMML patients, researchers found that 93% of patients had at least one somatic mutation in nine recurrently mutated genes—SRFS2, ASXL1, CBL, EZH2, JAK2V617F, KRAS, NRAS, RUNX1, and TET2 (Blood 2012 120:3080-3088).

However, Dr. Duraković noted that these mutations are found in other disorders as well, so this information may not be helpful in differentiating CMML from other disorders.

A 2015 study revealed a technique that does appear useful for identifying CMML—monocyte subset distribution analysis (Blood 2015 125(23): 3618–3626).

For this analysis, monocytes are divided into the following categories:

- Classical/MO1 (CD14bright/CD16−)

- Intermediate/MO2 (CD14bright/CD16+)

- Non-classical/MO3 (CD14dim/CD16+).

The researchers found that CMML patients had an increase in the fraction of classical monocytes (with a cutoff value of 94.0%), as compared to healthy control subjects, patients with another hematologic disorder, and patients with reactive monocytosis.

A 2018 study confirmed that monocyte subset distribution analysis could differentiate CMML from other hematologic disorders, with the exception of atypical CML (Am J Clin Pathol 2018 150(4):293-302).

This study also suggested that a decreased percentage of non-classical monocytes was more sensitive than an increased percentage of classical monocytes.

Despite the differences between these studies, “monocyte subset distribution analysis is showing promise as a method of identifying hard-to-identify CMML patients with ease and affordability,” Dr. Duraković said.

She added that the technique can be implemented in clinical practice using the HematoflowTM solution (Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2018 94(5):658-661).

Dr. Duraković did not report any conflicts of interest.

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Diagnosing chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) remains a challenge in 2018, according to a presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Even with updated World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, karyotyping, and genetic analyses, it can be difficult to distinguish CMML from other conditions, according to Nadira Duraković, MD, PhD, of the University Hospital Zagreb in Croatia.

However, Dr. Duraković said there are characteristics that differentiate CMML from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), and atypical chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Furthermore, studies have suggested that monocyte subset distribution analysis can be useful for diagnosing CMML.

Dr. Duraković began her presentation with an overview of the 2016 WHO classification of CMML (Blood 2016 127:2391-2405).

According to the WHO, patients have CMML if:

- They have persistent peripheral blood monocytosis (1×109/L) with monocytes accounting for 10% of the white blood cell count

- They do not meet WHO criteria for BCR-ABL1-positive CML, primary myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, or essential thrombocythemia

- There is no evidence of PCM1-JAK2 or PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1 rearrangement

- They have fewer than 20% blasts in the blood and bone marrow

- They have dysplasia in one or more myeloid lineages

- If myelodysplasia is absent or minimal, an acquired clonal cytogenetic or molecular genetic abnormality must be present.

Alternatively, if patients have monocytosis that has persisted for at least 3 months, and all other causes of monocytosis have been excluded, “you can say that your patient has CMML,” Dr. Duraković said.

Other causes of monocytosis include infections, malignancies, medications, inflammatory conditions, and other conditions such as pregnancy.

However, Dr. Duraković pointed out that the cause of monocytosis cannot always be determined, and, in some cases, CMML patients may not meet the WHO criteria.

“[T]here are cases where there just aren’t enough monocytes to fulfill the WHO criteria,” Dr. Duraković said. “You can have a patient with peripheral blood cytopenia and monocytosis who does not have 1,000 monocytes. Patients can have progressive dysplasia, can have splenomegaly, be really sick, but fail to meet WHO criteria.”

Distinguishing CMML from other conditions

“Differentiating CMML from myelodysplastic syndromes can be tough,” Dr. Duraković said. “There are dysplastic features that are present in CMML . . . but, in CMML, they are more subtle, and they are more difficult to appreciate than in myelodysplastic syndromes.”

The ratio of myeloid to erythroid cells is elevated in CMML, and patients may have atypical monocytes (paramyeloid cells) that are unique to CMML.

Dr. Duraković noted that megakaryocyte dysplasia in CMML can be characterized by “myeloproliferative megakaryocytes,” which are large cells that cluster and have hyperlobulated nuclei, or “MDS megakaryocytes,” which are small, solitary cells with hypolobulated nuclei.

She went on to explain that “MPN phenotype” CMML is characterized by leukocytosis, monocytosis, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and clinical features of myeloproliferation (fatigue, night sweats, bone pain, weight loss, etc.).

Thirty percent of cases are associated with splenomegaly, and 30% of patients can have an increase in bone marrow reticulin fibrosis.

Dr. Duraković also noted that a prior MPN diagnosis excludes CMML. The presence of common MPN mutations, such as JAK2, CALR, or MPL, suggests a patient has an MPN with monocytosis rather than CMML.

Patients who have unclassified MPNs or MDS, rather than CMML, either do not have 1,000 monocytes or the monocytes do not represent more than 10% of the differential, Dr. Duraković said.

She also noted that it can be difficult to differentiate CMML from atypical CML.

“Atypical CML is characterized by profound dysgranulopoiesis, absence of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, and neutrophilia,” Dr. Duraković explained. “Those patients [commonly] have monocytosis, but, here, that 10% rule is valuable because their monocytes comprise less than 10% of the entire white blood cell count.”

Karyotyping, genotyping, and immunophenotyping

“There is no disease-defining karyotype abnormality [in CMML],” Dr. Duraković noted.

She said 30% of patients have abnormal karyotype, and the most common abnormality is trisomy 8. Unlike in patients with MDS, del(5q) and monosomal karyotypes are infrequent in patients with CMML.

Similarly, there are no “disease-defining” mutations or genetic changes in CMML, although CMML is genetically distinct from MDS, Dr. Duraković said.

For instance, SRSF2 encodes a component of the spliceosome that is mutated in almost half of CMML patients and less than 10% of MDS patients. Likewise, ASLX1 and TET2 are “much more frequently involved” in CMML than in MDS, Dr. Duraković said.

In a 2012 study of 275 CMML patients, researchers found that 93% of patients had at least one somatic mutation in nine recurrently mutated genes—SRFS2, ASXL1, CBL, EZH2, JAK2V617F, KRAS, NRAS, RUNX1, and TET2 (Blood 2012 120:3080-3088).

However, Dr. Duraković noted that these mutations are found in other disorders as well, so this information may not be helpful in differentiating CMML from other disorders.

A 2015 study revealed a technique that does appear useful for identifying CMML—monocyte subset distribution analysis (Blood 2015 125(23): 3618–3626).

For this analysis, monocytes are divided into the following categories:

- Classical/MO1 (CD14bright/CD16−)

- Intermediate/MO2 (CD14bright/CD16+)

- Non-classical/MO3 (CD14dim/CD16+).

The researchers found that CMML patients had an increase in the fraction of classical monocytes (with a cutoff value of 94.0%), as compared to healthy control subjects, patients with another hematologic disorder, and patients with reactive monocytosis.

A 2018 study confirmed that monocyte subset distribution analysis could differentiate CMML from other hematologic disorders, with the exception of atypical CML (Am J Clin Pathol 2018 150(4):293-302).

This study also suggested that a decreased percentage of non-classical monocytes was more sensitive than an increased percentage of classical monocytes.

Despite the differences between these studies, “monocyte subset distribution analysis is showing promise as a method of identifying hard-to-identify CMML patients with ease and affordability,” Dr. Duraković said.

She added that the technique can be implemented in clinical practice using the HematoflowTM solution (Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2018 94(5):658-661).

Dr. Duraković did not report any conflicts of interest.