User login

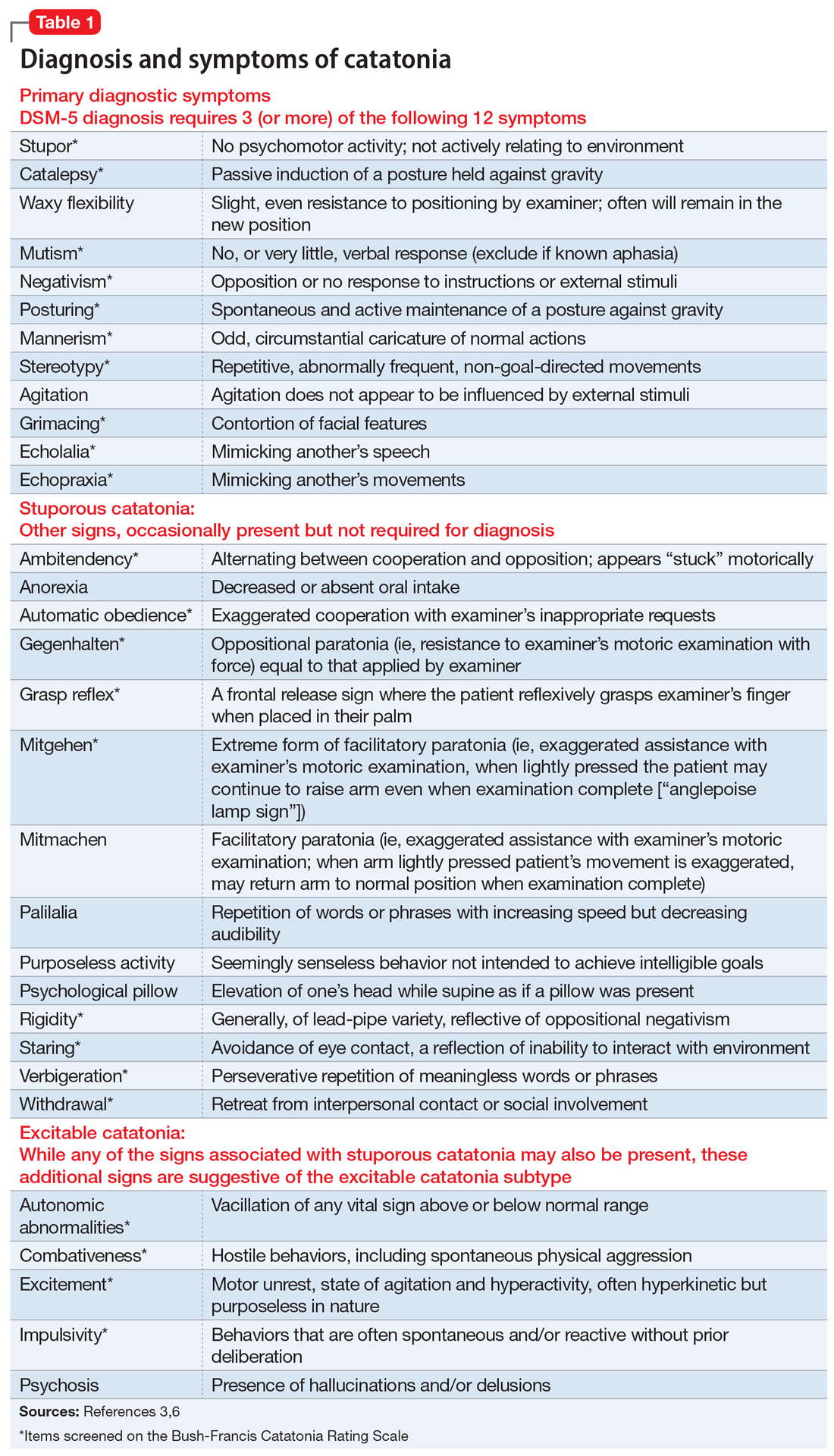

Mr. W, age 50, who has been diagnosed with hypertension and catatonia associated with schizophrenia, is brought to the emergency department by his case manager for evaluation of increasing disorganization, inability to function, and nonadherence to medications. He has not been bathing, eating, or drinking. During the admission interview, he is mute, and is noted to have purposeless activity, alternating between rocking from leg to leg to pacing in circles. At times Mr. W holds a rigid, prayer-type posture with his arms. Negativism is present, primarily opposition to interviewer requests.

Previously stable on

On the inpatient psychiatry unit, Mr. W continues to be mute, staying in bed except to use the bathroom. He refuses all food and fluids. The team initiates subcutaneous

Continue to: Medical complications can be fatal

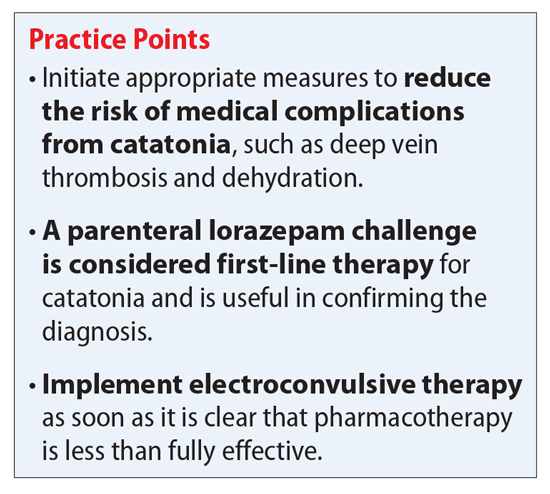

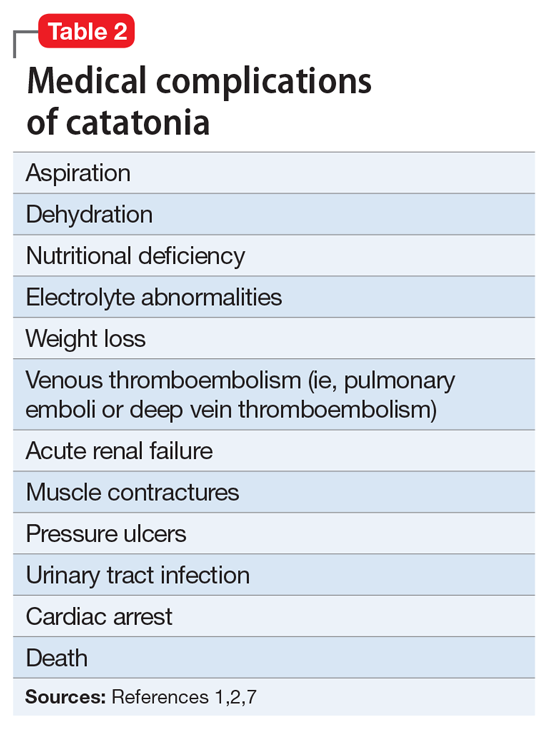

Medical complications can be fatal

Treatment usually starts with lorazepam

Benzodiazepines are a first-line option for the management of catatonia.2,5 Controversy exists as to effectiveness of different routes of administration. Generally, IV lorazepam is preferred due to its ease of administration, fast onset, and longer duration of action.1 Some inpatient psychiatric units are unable to administer IV benzodiazepines; in these scenarios, IM administration is preferred to oral benzodiazepines.

The initial lorazepam challenge dose should be 2 mg. A positive response to the lorazepam challenge often confirms the catatonia diagnosis.2,7 This challenge should be followed by maintenance doses ranging from 6 to 8 mg/d in divided doses (3 or 4 times a day). Higher doses (up to 24 mg/d) are sometimes used.2,5,8 A recent case report described catatonia remission using lorazepam, 28 mg/d, after unsuccessful ECT.9 The lorazepam dose prior to ECT was 8 mg/d.9 Response is usually seen within 3 to 7 days of an adequate dose.2,8 Parenteral lorazepam typically is continued for several days before converting to oral lorazepam.1 Approximately 70% to 80% of patients with catatonia will show improvement in symptoms with lorazepam.2,7,8

The optimal duration of benzodiazepine treatment is unclear.2 In some cases, once remission of the underlying illness is achieved, benzodiazepines are discontinued.2 However, in other cases, symptoms of catatonia may emerge when lorazepam is tapered, therefore suggesting the need for a longer duration of treatment.2 Despite this high rate of improvement, many patients ultimately receive ECT due to unsustained response or to prevent future episodes of catatonia.

A recent review of 60 Turkish patients with catatonia found 91.7% (n = 55) received oral lorazepam (up to 15 mg/d) as the first-line therapy.7 Improvement was seen in 23.7% (n = 13) of patients treated with lorazepam, yet 70% (n = 42) showed either no response or partial response, and ultimately received ECT in combination with lorazepam.7 The lower improvement rate seen in this review may be secondary to the use of oral lorazepam instead of parenteral, or may highlight the frequency in which patients ultimately go on to receive ECT.

Continue to: ECT

ECT. If high doses of benzodiazepines are not effective within 48 to 72 hours, ECT should be considered.1,7 ECT should be considered sooner for patients with life-threatening catatonia or those who present with excited features or malignant catatonia.1,2,7 In patients with catatonia, ECT response rates range from 80% to 100%.2,7 Unal et al7 reported a 100% response rate if ECT was used as the first-line treatment (n = 5), and a 92.9% (n = 39) response rate after adding ECT to lorazepam. Lorazepam may interfere with the seizure threshold, but if indicated, this medication can be continued.2 A minimum of 6 ECT treatments are suggested; however, as many as 20 treatments have been needed.1 Mr. W required a total of 18 ECT treatments. In some cases, maintenance ECT may be required.2

Antipsychotics. Discontinuation of antipsychotics is generally encouraged in patients presenting with catatonia.2,7,8 Antipsychotics carry a risk of potentially worsening catatonia, conversion to malignant catatonia, or precipitation of NMS; therefore, carefully weigh the risks vs benefits.1,2 If catatonia is secondary to psychosis, as in Mr. W’s case, antipsychotics may be considered once catatonia improves.2 If an antipsychotic is warranted, consider aripiprazole (because of its D2 partial agonist activity) or low-dose olanzapine.1,2 If catatonia is secondary to clozapine withdrawal, the initial therapy should be clozapine re-initiation.1 Although high-potency agents, such as haloperidol and risperidone, typically are not preferred, risperidone was restarted for Mr. W because of his history of response to and tolerability of this medication during a previous catatonic episode.

Other treatments. In a recent review, Beach et al1 described the use of additional agents, mostly in a small number of positive case reports, for managing catatonia. These included:

- zolpidem (zolpidem 10 mg as a challenge test, and doses of ≤40 mg/d)

- the N-methyl-

D -aspartic acid antagonists amantadine (100 to 600 mg/d) or memantine (5 to 20 mg/d) - carbidopa/levodopa

- methylphenidate

- antiepileptics (eg, carbamazepine, topiramate, and divalproex sodium)

- anticholinergics.1,2

Lithium has been used in attempts to prevent recurrent catatonia with limited success.2 There are also a few reports of using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to manage catatonia.1

Beach et al1 proposed a treatment algorithm in which IV lorazepam (Step 1) and ECT (Step 2) remain the preferred treatments. Next, for Step 3 consider a glutamate antagonist (amantadine or memantine), followed by an antiepileptic (Step 4), and lastly an atypical antipsychotic (aripiprazole, olanzapine, or clozapine) in combination with lorazepam (Step 5).

When indicated, don’t delay ECT

Initial management of catatonia is with a benzodiazepine challenge. Ultimately, the gold-standard treatment of catatonia that does not improve with benzodiazepines is ECT, and ECT should be implemented as soon as it is clear that pharmacotherapy is less than fully effective. Consider ECT initially in life-threatening cases and for patients with malignant catatonia. Although additional agents and TMS have been explored, these should be reserved for patients who fail to respond to, or who are not candidates for, benzodiazepines or ECT.

CASE CONTINUED

After 5 ECT treatments, Mr. W says a few words, but he communicates primarily with gestures (primarily waving people away). After 10 to 12 ECT treatments, Mr. W becomes more interactive and conversant, and his nutrition improves; however, he still exhibits symptoms of catatonia and is not at baseline. He undergoes a total of 18 ECT treatments. Antipsychotics were initially discontinued; however, given Mr. W’s improvement with ECT and the presence of auditory hallucinations, oral risperidone is restarted and titrated to 2 mg, 2 times a day, and he is transitioned back to paliperidone palmitate before he is discharged. Lorazepam is tapered and discontinued. Mr. W is discharged back to his nursing home and is interactive (laughing and joking with family) and attending to his activities of daily living. Unfortunately, Mr. W did not followup with the recommendation for maintenance ECT, and adherence to paliperidone palmitate injections is unknown. Mr. W presented to our facility again 6 months later with symptoms of catatonia and ultimately transferred to a state hospital.

Related Resources

- Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: A clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. • Carroll BT, Spiegel DR. Catatonia on the consultation liaison service and other clinical settings. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Pub Inc.; 2016.

- Benarous X, Raffin M, Ferrafiat V, et al. Catatonia in children and adolescents: new perspectives. Schizophr Res. 2018;200:56-67.

- Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. What is NMSIS? http://www.mhaus.org/nmsis/about-us/ what-is-nmsis/.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carbidopa/Levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Divalproex Sodium • Depakote

Enoxaparin • Lovenox

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Lurasidone • Latuda

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

Topiramate • Topamax

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Beach SR, Gomez-Bernal F, Huffman JC, et al. Alternative treatment strategies for catatonia: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;48:1-19.

2. Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:1-6.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Pileggi DJ, Cook AM. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: focus on treatment and rechallenge. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):973-981.

5. Ohi K, Kuwata A, Shimada T, et al. Response to benzodiazepines and clinical course in malignant catatonia associated with schizophrenia: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(16):e6566. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006566.

6. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

7. Unal A, Altindag A, Demir B, et al. The use of lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of catatonia: treatment characteristics and outcomes in 60 patients. J ECT. 2017;33(4):290-293.

8. Fink M, Taylor MA. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is malignant catatonia, warranting treatments efficacious for catatonia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):1182-1183.

9. van der Markt A, Heller HM, van Exel E. A woman with catatonia, what to do after ECT fails: a case report. J ECT. 2016;32(3):e6-7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000290.

Mr. W, age 50, who has been diagnosed with hypertension and catatonia associated with schizophrenia, is brought to the emergency department by his case manager for evaluation of increasing disorganization, inability to function, and nonadherence to medications. He has not been bathing, eating, or drinking. During the admission interview, he is mute, and is noted to have purposeless activity, alternating between rocking from leg to leg to pacing in circles. At times Mr. W holds a rigid, prayer-type posture with his arms. Negativism is present, primarily opposition to interviewer requests.

Previously stable on

On the inpatient psychiatry unit, Mr. W continues to be mute, staying in bed except to use the bathroom. He refuses all food and fluids. The team initiates subcutaneous

Continue to: Medical complications can be fatal

Medical complications can be fatal

Treatment usually starts with lorazepam

Benzodiazepines are a first-line option for the management of catatonia.2,5 Controversy exists as to effectiveness of different routes of administration. Generally, IV lorazepam is preferred due to its ease of administration, fast onset, and longer duration of action.1 Some inpatient psychiatric units are unable to administer IV benzodiazepines; in these scenarios, IM administration is preferred to oral benzodiazepines.

The initial lorazepam challenge dose should be 2 mg. A positive response to the lorazepam challenge often confirms the catatonia diagnosis.2,7 This challenge should be followed by maintenance doses ranging from 6 to 8 mg/d in divided doses (3 or 4 times a day). Higher doses (up to 24 mg/d) are sometimes used.2,5,8 A recent case report described catatonia remission using lorazepam, 28 mg/d, after unsuccessful ECT.9 The lorazepam dose prior to ECT was 8 mg/d.9 Response is usually seen within 3 to 7 days of an adequate dose.2,8 Parenteral lorazepam typically is continued for several days before converting to oral lorazepam.1 Approximately 70% to 80% of patients with catatonia will show improvement in symptoms with lorazepam.2,7,8

The optimal duration of benzodiazepine treatment is unclear.2 In some cases, once remission of the underlying illness is achieved, benzodiazepines are discontinued.2 However, in other cases, symptoms of catatonia may emerge when lorazepam is tapered, therefore suggesting the need for a longer duration of treatment.2 Despite this high rate of improvement, many patients ultimately receive ECT due to unsustained response or to prevent future episodes of catatonia.

A recent review of 60 Turkish patients with catatonia found 91.7% (n = 55) received oral lorazepam (up to 15 mg/d) as the first-line therapy.7 Improvement was seen in 23.7% (n = 13) of patients treated with lorazepam, yet 70% (n = 42) showed either no response or partial response, and ultimately received ECT in combination with lorazepam.7 The lower improvement rate seen in this review may be secondary to the use of oral lorazepam instead of parenteral, or may highlight the frequency in which patients ultimately go on to receive ECT.

Continue to: ECT

ECT. If high doses of benzodiazepines are not effective within 48 to 72 hours, ECT should be considered.1,7 ECT should be considered sooner for patients with life-threatening catatonia or those who present with excited features or malignant catatonia.1,2,7 In patients with catatonia, ECT response rates range from 80% to 100%.2,7 Unal et al7 reported a 100% response rate if ECT was used as the first-line treatment (n = 5), and a 92.9% (n = 39) response rate after adding ECT to lorazepam. Lorazepam may interfere with the seizure threshold, but if indicated, this medication can be continued.2 A minimum of 6 ECT treatments are suggested; however, as many as 20 treatments have been needed.1 Mr. W required a total of 18 ECT treatments. In some cases, maintenance ECT may be required.2

Antipsychotics. Discontinuation of antipsychotics is generally encouraged in patients presenting with catatonia.2,7,8 Antipsychotics carry a risk of potentially worsening catatonia, conversion to malignant catatonia, or precipitation of NMS; therefore, carefully weigh the risks vs benefits.1,2 If catatonia is secondary to psychosis, as in Mr. W’s case, antipsychotics may be considered once catatonia improves.2 If an antipsychotic is warranted, consider aripiprazole (because of its D2 partial agonist activity) or low-dose olanzapine.1,2 If catatonia is secondary to clozapine withdrawal, the initial therapy should be clozapine re-initiation.1 Although high-potency agents, such as haloperidol and risperidone, typically are not preferred, risperidone was restarted for Mr. W because of his history of response to and tolerability of this medication during a previous catatonic episode.

Other treatments. In a recent review, Beach et al1 described the use of additional agents, mostly in a small number of positive case reports, for managing catatonia. These included:

- zolpidem (zolpidem 10 mg as a challenge test, and doses of ≤40 mg/d)

- the N-methyl-

D -aspartic acid antagonists amantadine (100 to 600 mg/d) or memantine (5 to 20 mg/d) - carbidopa/levodopa

- methylphenidate

- antiepileptics (eg, carbamazepine, topiramate, and divalproex sodium)

- anticholinergics.1,2

Lithium has been used in attempts to prevent recurrent catatonia with limited success.2 There are also a few reports of using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to manage catatonia.1

Beach et al1 proposed a treatment algorithm in which IV lorazepam (Step 1) and ECT (Step 2) remain the preferred treatments. Next, for Step 3 consider a glutamate antagonist (amantadine or memantine), followed by an antiepileptic (Step 4), and lastly an atypical antipsychotic (aripiprazole, olanzapine, or clozapine) in combination with lorazepam (Step 5).

When indicated, don’t delay ECT

Initial management of catatonia is with a benzodiazepine challenge. Ultimately, the gold-standard treatment of catatonia that does not improve with benzodiazepines is ECT, and ECT should be implemented as soon as it is clear that pharmacotherapy is less than fully effective. Consider ECT initially in life-threatening cases and for patients with malignant catatonia. Although additional agents and TMS have been explored, these should be reserved for patients who fail to respond to, or who are not candidates for, benzodiazepines or ECT.

CASE CONTINUED

After 5 ECT treatments, Mr. W says a few words, but he communicates primarily with gestures (primarily waving people away). After 10 to 12 ECT treatments, Mr. W becomes more interactive and conversant, and his nutrition improves; however, he still exhibits symptoms of catatonia and is not at baseline. He undergoes a total of 18 ECT treatments. Antipsychotics were initially discontinued; however, given Mr. W’s improvement with ECT and the presence of auditory hallucinations, oral risperidone is restarted and titrated to 2 mg, 2 times a day, and he is transitioned back to paliperidone palmitate before he is discharged. Lorazepam is tapered and discontinued. Mr. W is discharged back to his nursing home and is interactive (laughing and joking with family) and attending to his activities of daily living. Unfortunately, Mr. W did not followup with the recommendation for maintenance ECT, and adherence to paliperidone palmitate injections is unknown. Mr. W presented to our facility again 6 months later with symptoms of catatonia and ultimately transferred to a state hospital.

Related Resources

- Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: A clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. • Carroll BT, Spiegel DR. Catatonia on the consultation liaison service and other clinical settings. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Pub Inc.; 2016.

- Benarous X, Raffin M, Ferrafiat V, et al. Catatonia in children and adolescents: new perspectives. Schizophr Res. 2018;200:56-67.

- Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. What is NMSIS? http://www.mhaus.org/nmsis/about-us/ what-is-nmsis/.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carbidopa/Levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Divalproex Sodium • Depakote

Enoxaparin • Lovenox

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Lurasidone • Latuda

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

Topiramate • Topamax

Zolpidem • Ambien

Mr. W, age 50, who has been diagnosed with hypertension and catatonia associated with schizophrenia, is brought to the emergency department by his case manager for evaluation of increasing disorganization, inability to function, and nonadherence to medications. He has not been bathing, eating, or drinking. During the admission interview, he is mute, and is noted to have purposeless activity, alternating between rocking from leg to leg to pacing in circles. At times Mr. W holds a rigid, prayer-type posture with his arms. Negativism is present, primarily opposition to interviewer requests.

Previously stable on

On the inpatient psychiatry unit, Mr. W continues to be mute, staying in bed except to use the bathroom. He refuses all food and fluids. The team initiates subcutaneous

Continue to: Medical complications can be fatal

Medical complications can be fatal

Treatment usually starts with lorazepam

Benzodiazepines are a first-line option for the management of catatonia.2,5 Controversy exists as to effectiveness of different routes of administration. Generally, IV lorazepam is preferred due to its ease of administration, fast onset, and longer duration of action.1 Some inpatient psychiatric units are unable to administer IV benzodiazepines; in these scenarios, IM administration is preferred to oral benzodiazepines.

The initial lorazepam challenge dose should be 2 mg. A positive response to the lorazepam challenge often confirms the catatonia diagnosis.2,7 This challenge should be followed by maintenance doses ranging from 6 to 8 mg/d in divided doses (3 or 4 times a day). Higher doses (up to 24 mg/d) are sometimes used.2,5,8 A recent case report described catatonia remission using lorazepam, 28 mg/d, after unsuccessful ECT.9 The lorazepam dose prior to ECT was 8 mg/d.9 Response is usually seen within 3 to 7 days of an adequate dose.2,8 Parenteral lorazepam typically is continued for several days before converting to oral lorazepam.1 Approximately 70% to 80% of patients with catatonia will show improvement in symptoms with lorazepam.2,7,8

The optimal duration of benzodiazepine treatment is unclear.2 In some cases, once remission of the underlying illness is achieved, benzodiazepines are discontinued.2 However, in other cases, symptoms of catatonia may emerge when lorazepam is tapered, therefore suggesting the need for a longer duration of treatment.2 Despite this high rate of improvement, many patients ultimately receive ECT due to unsustained response or to prevent future episodes of catatonia.

A recent review of 60 Turkish patients with catatonia found 91.7% (n = 55) received oral lorazepam (up to 15 mg/d) as the first-line therapy.7 Improvement was seen in 23.7% (n = 13) of patients treated with lorazepam, yet 70% (n = 42) showed either no response or partial response, and ultimately received ECT in combination with lorazepam.7 The lower improvement rate seen in this review may be secondary to the use of oral lorazepam instead of parenteral, or may highlight the frequency in which patients ultimately go on to receive ECT.

Continue to: ECT

ECT. If high doses of benzodiazepines are not effective within 48 to 72 hours, ECT should be considered.1,7 ECT should be considered sooner for patients with life-threatening catatonia or those who present with excited features or malignant catatonia.1,2,7 In patients with catatonia, ECT response rates range from 80% to 100%.2,7 Unal et al7 reported a 100% response rate if ECT was used as the first-line treatment (n = 5), and a 92.9% (n = 39) response rate after adding ECT to lorazepam. Lorazepam may interfere with the seizure threshold, but if indicated, this medication can be continued.2 A minimum of 6 ECT treatments are suggested; however, as many as 20 treatments have been needed.1 Mr. W required a total of 18 ECT treatments. In some cases, maintenance ECT may be required.2

Antipsychotics. Discontinuation of antipsychotics is generally encouraged in patients presenting with catatonia.2,7,8 Antipsychotics carry a risk of potentially worsening catatonia, conversion to malignant catatonia, or precipitation of NMS; therefore, carefully weigh the risks vs benefits.1,2 If catatonia is secondary to psychosis, as in Mr. W’s case, antipsychotics may be considered once catatonia improves.2 If an antipsychotic is warranted, consider aripiprazole (because of its D2 partial agonist activity) or low-dose olanzapine.1,2 If catatonia is secondary to clozapine withdrawal, the initial therapy should be clozapine re-initiation.1 Although high-potency agents, such as haloperidol and risperidone, typically are not preferred, risperidone was restarted for Mr. W because of his history of response to and tolerability of this medication during a previous catatonic episode.

Other treatments. In a recent review, Beach et al1 described the use of additional agents, mostly in a small number of positive case reports, for managing catatonia. These included:

- zolpidem (zolpidem 10 mg as a challenge test, and doses of ≤40 mg/d)

- the N-methyl-

D -aspartic acid antagonists amantadine (100 to 600 mg/d) or memantine (5 to 20 mg/d) - carbidopa/levodopa

- methylphenidate

- antiepileptics (eg, carbamazepine, topiramate, and divalproex sodium)

- anticholinergics.1,2

Lithium has been used in attempts to prevent recurrent catatonia with limited success.2 There are also a few reports of using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to manage catatonia.1

Beach et al1 proposed a treatment algorithm in which IV lorazepam (Step 1) and ECT (Step 2) remain the preferred treatments. Next, for Step 3 consider a glutamate antagonist (amantadine or memantine), followed by an antiepileptic (Step 4), and lastly an atypical antipsychotic (aripiprazole, olanzapine, or clozapine) in combination with lorazepam (Step 5).

When indicated, don’t delay ECT

Initial management of catatonia is with a benzodiazepine challenge. Ultimately, the gold-standard treatment of catatonia that does not improve with benzodiazepines is ECT, and ECT should be implemented as soon as it is clear that pharmacotherapy is less than fully effective. Consider ECT initially in life-threatening cases and for patients with malignant catatonia. Although additional agents and TMS have been explored, these should be reserved for patients who fail to respond to, or who are not candidates for, benzodiazepines or ECT.

CASE CONTINUED

After 5 ECT treatments, Mr. W says a few words, but he communicates primarily with gestures (primarily waving people away). After 10 to 12 ECT treatments, Mr. W becomes more interactive and conversant, and his nutrition improves; however, he still exhibits symptoms of catatonia and is not at baseline. He undergoes a total of 18 ECT treatments. Antipsychotics were initially discontinued; however, given Mr. W’s improvement with ECT and the presence of auditory hallucinations, oral risperidone is restarted and titrated to 2 mg, 2 times a day, and he is transitioned back to paliperidone palmitate before he is discharged. Lorazepam is tapered and discontinued. Mr. W is discharged back to his nursing home and is interactive (laughing and joking with family) and attending to his activities of daily living. Unfortunately, Mr. W did not followup with the recommendation for maintenance ECT, and adherence to paliperidone palmitate injections is unknown. Mr. W presented to our facility again 6 months later with symptoms of catatonia and ultimately transferred to a state hospital.

Related Resources

- Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: A clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. • Carroll BT, Spiegel DR. Catatonia on the consultation liaison service and other clinical settings. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Pub Inc.; 2016.

- Benarous X, Raffin M, Ferrafiat V, et al. Catatonia in children and adolescents: new perspectives. Schizophr Res. 2018;200:56-67.

- Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. What is NMSIS? http://www.mhaus.org/nmsis/about-us/ what-is-nmsis/.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Carbidopa/Levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Divalproex Sodium • Depakote

Enoxaparin • Lovenox

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Lurasidone • Latuda

Memantine • Namenda

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone long-acting injection • Risperdal Consta

Topiramate • Topamax

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Beach SR, Gomez-Bernal F, Huffman JC, et al. Alternative treatment strategies for catatonia: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;48:1-19.

2. Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:1-6.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Pileggi DJ, Cook AM. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: focus on treatment and rechallenge. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):973-981.

5. Ohi K, Kuwata A, Shimada T, et al. Response to benzodiazepines and clinical course in malignant catatonia associated with schizophrenia: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(16):e6566. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006566.

6. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

7. Unal A, Altindag A, Demir B, et al. The use of lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of catatonia: treatment characteristics and outcomes in 60 patients. J ECT. 2017;33(4):290-293.

8. Fink M, Taylor MA. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is malignant catatonia, warranting treatments efficacious for catatonia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):1182-1183.

9. van der Markt A, Heller HM, van Exel E. A woman with catatonia, what to do after ECT fails: a case report. J ECT. 2016;32(3):e6-7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000290.

1. Beach SR, Gomez-Bernal F, Huffman JC, et al. Alternative treatment strategies for catatonia: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;48:1-19.

2. Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:1-6.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Pileggi DJ, Cook AM. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: focus on treatment and rechallenge. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):973-981.

5. Ohi K, Kuwata A, Shimada T, et al. Response to benzodiazepines and clinical course in malignant catatonia associated with schizophrenia: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(16):e6566. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006566.

6. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):129-136.

7. Unal A, Altindag A, Demir B, et al. The use of lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of catatonia: treatment characteristics and outcomes in 60 patients. J ECT. 2017;33(4):290-293.

8. Fink M, Taylor MA. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is malignant catatonia, warranting treatments efficacious for catatonia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):1182-1183.

9. van der Markt A, Heller HM, van Exel E. A woman with catatonia, what to do after ECT fails: a case report. J ECT. 2016;32(3):e6-7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000290.