User login

Case

A previously healthy 4-month-old girl was brought into the ED for concerns of alcohol ingestion. Reportedly, the infant’s father reconstituted 4 ounces of powdered formula using what he thought was water from an unmarked bottle in his refrigerator. He later realized that the bottle contained rum, although he still let the child finish the 4 ounces of formula in the hopes that she would vomit—which did not occur.

Upon arrival to the ED, the infant’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 100/61 mm Hg; heart rate, 155 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 36 breaths/minute; and temperature, normal. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. A rapid bedside blood glucose test was 89 mg/dL. The infant’s physical examination was unremarkable. She appeared active but hungry, had a strong cry, and had a developmentally appropriate gross neurological examination.

How does ethanol exposure in children typically occur?

Recent reports from the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System demonstrate that ethanol exposures comprise 1% to 3% of total exposures in children aged ≤5 years.

The most common sources are ethanol-containing beverages, mouthwash, and cologne/perfume.1 Ethanol can also be found as a solvent for certain pediatric liquid medications (eg, ranitidine) or in flavor extracts (eg, vanilla extract, orange extract). Any clear alcohol (eg, vodka, gin, rum) stored in an accessible site, such as a refrigerator, may be mistaken for water. In many reports, a caregiver unintentionally used the alcohol to reconstitute formula; however, intentional provision of alcohol to toddlers, usually as a sedative, is a recurring concern.2

What are the clinical concerns in children with ethanol intoxication?

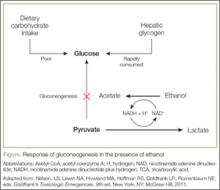

Under usual conditions, a normal serum glucose concentration is maintained from ingested carbohydrates and via glycogenolysis of hepatic glycogen stores. Such glycogen reserves can sustain normal blood glucose concentrations for several hours in adults but for a shorter period in children. Once glycogen is depleted, as is common after an overnight fast, glucose can be generated through gluconeogenesis.

However, in the presence of ethanol (Figure), the excessive reducing potential (ie, NADH) that results from ethanol metabolism shunts pyruvate away from the gluconeogenic pathway (toward lactate), inhibiting glucose production. Unlike adults, children and infants, who have relatively low glycogen reserves, are at significant risk for hypoglycemia following ethanol exposure. This represents the largest contributor to morbidity and mortality of children with ethanol intoxication.3 Patients with hypoglycemia can have a highly variable clinical presentation including agitation, seizures, focality, or coma.4

Case Continuation

Intravenous (IV) access was obtained, and the patient was placed on a dextrose-containing fluid at 1.5 times the maintenance flow rate. Pertinent laboratory studies revealed a serum glucose level of 90 mg/dL, normal electrolyte panel, and an initial blood alcohol concentration of 337 mg/dL (approximately 30 minutes postingestion).

How do children with ethanol intoxication present?

While there is some variation in clinical effects among nontolerant adults, acute ethanol intoxication with a serum concentration >250 mg/dL is frequently associated with stupor, respiratory depression, and hypotension. A concentration >400 mg/dL may be associated with coma or apnea. Although similar clinical effects are expected in adolescents and children, infants often have counterintuitive clinical findings.

To date, eight cases of significant infant ethanol exposure exist in the literature (age range, 29 days to 9 months; ethanol concentration, 183-524 mg/dL). Respiratory depression was absent in all cases.5-9 In all but two cases, the neurological examination revealed only subtle decreases in interaction or tone. The remaining two children were described as obtunded and flaccid (ethanol levels, 405 mg/dL and 524 mg/dL, respectively) and were intubated for airway protection despite normal respiratory rates.7,10

The incongruence between the clinical findings (both the neurological examination and respiratory effects) and the ethanol concentration is difficult to explain. It may be due to age-related neurological immaturity or a limited ability to perform the required detailed neurological examinations in children. In particular, the relatively preserved level of consciousness, despite an otherwise coma-inducing ethanol concentration, is unique to infants. Accordingly, there should be a low threshold to check ethanol concentrations in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events, altered mental status, decreased tone, or unexplained hypoglycemia or hypothermia.

What is the estimated time to sobriety in infants?

Ethanol is eliminated via a hepatic enzymatic oxidation pathway that becomes saturated at low serum levels. In nontolerant adults, this results in a zero-order kinetic elimination pattern with an ethanol elimination rate of approximately 20 mg/dL per hour. Anecdotally, it had been thought that children clear ethanol at roughly double this rate via unclear mechanisms. However, a review of published kinetic data suggests the actual rate of clearance may not differ substantially from adults (range, 19-34 mg/dL per hour).5-7,10,11

Case Conclusion

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care pediatric hospital for continued management, where the markedly elevated serum ethanol concentration was confirmed. She was maintained on a dextrose-containing IV fluid and observed overnight without development of any complications. Serial serum ethanol concentrations were performed and complete clearance was achieved approximately 20 hours postingestion, suggesting a metabolic rate of 16 mg/dL per hour. The infant was discharged home with supervision by child protective services.

Dr Boroughf is a toxicology fellow, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Henretig is an attending toxicologist, department of emergency medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51(10):949-1229.

- Wood JN, Pecker LH, Russo ME, Henretig F, Christian CW. Evaluation and referral for child maltreatment in pediatric poisoning victims. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(4):362-369.

- Lamminpää A. Alcohol intoxication in childhood and adolescence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(1):5-12.

- Malouf R, Brust JC. Hypoglycemia: causes, neurological manifestations, and outcome. Ann Neurol.1985;17(5):421-430.

- Chikava K, Lower DR, Frangiskakis SH, Sepulveda JL, Virji MA, Rao KN. Acute ethanol intoxication in a 7-month old-infant. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7(4):400-402.

- Ford JB, Wayment MT, Albertson TE, Owen KP, Radke JB, Sutter ME. Elimination kinetics of ethanol in a 5-week-old infant and a literature review of infant ethanol pharmacokinetics. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:250716. doi:10.1155/2013/250716

- McCormick T, Levine M, Knox O, Claudius I. Ethanol ingestion in two infants under 2 months old: a previously unreported cause of ALTE. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2);e604-e607.

- Fong HF, Muller AA. An unexpected clinical course in a 29-day-old infant with ethanol exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(2):111-113.

- Iyer SS, Haupt A, Henretig FM. Pick your poison: straight from the spring? Ped Emerg Care. 2009;25(3):194-196.

- Edmunds SM, Ajizian SJ, Liguori A. Acute obtundation in a 9-month-old patient: ethanol ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(10):739-741.

- Simon HK, Cox JM, Sucov A, Linakis JG. Serum ethanol clearance in intoxicated children and adolescents presenting to the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(6):520-524.

Case

A previously healthy 4-month-old girl was brought into the ED for concerns of alcohol ingestion. Reportedly, the infant’s father reconstituted 4 ounces of powdered formula using what he thought was water from an unmarked bottle in his refrigerator. He later realized that the bottle contained rum, although he still let the child finish the 4 ounces of formula in the hopes that she would vomit—which did not occur.

Upon arrival to the ED, the infant’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 100/61 mm Hg; heart rate, 155 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 36 breaths/minute; and temperature, normal. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. A rapid bedside blood glucose test was 89 mg/dL. The infant’s physical examination was unremarkable. She appeared active but hungry, had a strong cry, and had a developmentally appropriate gross neurological examination.

How does ethanol exposure in children typically occur?

Recent reports from the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System demonstrate that ethanol exposures comprise 1% to 3% of total exposures in children aged ≤5 years.

The most common sources are ethanol-containing beverages, mouthwash, and cologne/perfume.1 Ethanol can also be found as a solvent for certain pediatric liquid medications (eg, ranitidine) or in flavor extracts (eg, vanilla extract, orange extract). Any clear alcohol (eg, vodka, gin, rum) stored in an accessible site, such as a refrigerator, may be mistaken for water. In many reports, a caregiver unintentionally used the alcohol to reconstitute formula; however, intentional provision of alcohol to toddlers, usually as a sedative, is a recurring concern.2

What are the clinical concerns in children with ethanol intoxication?

Under usual conditions, a normal serum glucose concentration is maintained from ingested carbohydrates and via glycogenolysis of hepatic glycogen stores. Such glycogen reserves can sustain normal blood glucose concentrations for several hours in adults but for a shorter period in children. Once glycogen is depleted, as is common after an overnight fast, glucose can be generated through gluconeogenesis.

However, in the presence of ethanol (Figure), the excessive reducing potential (ie, NADH) that results from ethanol metabolism shunts pyruvate away from the gluconeogenic pathway (toward lactate), inhibiting glucose production. Unlike adults, children and infants, who have relatively low glycogen reserves, are at significant risk for hypoglycemia following ethanol exposure. This represents the largest contributor to morbidity and mortality of children with ethanol intoxication.3 Patients with hypoglycemia can have a highly variable clinical presentation including agitation, seizures, focality, or coma.4

Case Continuation

Intravenous (IV) access was obtained, and the patient was placed on a dextrose-containing fluid at 1.5 times the maintenance flow rate. Pertinent laboratory studies revealed a serum glucose level of 90 mg/dL, normal electrolyte panel, and an initial blood alcohol concentration of 337 mg/dL (approximately 30 minutes postingestion).

How do children with ethanol intoxication present?

While there is some variation in clinical effects among nontolerant adults, acute ethanol intoxication with a serum concentration >250 mg/dL is frequently associated with stupor, respiratory depression, and hypotension. A concentration >400 mg/dL may be associated with coma or apnea. Although similar clinical effects are expected in adolescents and children, infants often have counterintuitive clinical findings.

To date, eight cases of significant infant ethanol exposure exist in the literature (age range, 29 days to 9 months; ethanol concentration, 183-524 mg/dL). Respiratory depression was absent in all cases.5-9 In all but two cases, the neurological examination revealed only subtle decreases in interaction or tone. The remaining two children were described as obtunded and flaccid (ethanol levels, 405 mg/dL and 524 mg/dL, respectively) and were intubated for airway protection despite normal respiratory rates.7,10

The incongruence between the clinical findings (both the neurological examination and respiratory effects) and the ethanol concentration is difficult to explain. It may be due to age-related neurological immaturity or a limited ability to perform the required detailed neurological examinations in children. In particular, the relatively preserved level of consciousness, despite an otherwise coma-inducing ethanol concentration, is unique to infants. Accordingly, there should be a low threshold to check ethanol concentrations in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events, altered mental status, decreased tone, or unexplained hypoglycemia or hypothermia.

What is the estimated time to sobriety in infants?

Ethanol is eliminated via a hepatic enzymatic oxidation pathway that becomes saturated at low serum levels. In nontolerant adults, this results in a zero-order kinetic elimination pattern with an ethanol elimination rate of approximately 20 mg/dL per hour. Anecdotally, it had been thought that children clear ethanol at roughly double this rate via unclear mechanisms. However, a review of published kinetic data suggests the actual rate of clearance may not differ substantially from adults (range, 19-34 mg/dL per hour).5-7,10,11

Case Conclusion

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care pediatric hospital for continued management, where the markedly elevated serum ethanol concentration was confirmed. She was maintained on a dextrose-containing IV fluid and observed overnight without development of any complications. Serial serum ethanol concentrations were performed and complete clearance was achieved approximately 20 hours postingestion, suggesting a metabolic rate of 16 mg/dL per hour. The infant was discharged home with supervision by child protective services.

Dr Boroughf is a toxicology fellow, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Henretig is an attending toxicologist, department of emergency medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Case

A previously healthy 4-month-old girl was brought into the ED for concerns of alcohol ingestion. Reportedly, the infant’s father reconstituted 4 ounces of powdered formula using what he thought was water from an unmarked bottle in his refrigerator. He later realized that the bottle contained rum, although he still let the child finish the 4 ounces of formula in the hopes that she would vomit—which did not occur.

Upon arrival to the ED, the infant’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 100/61 mm Hg; heart rate, 155 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 36 breaths/minute; and temperature, normal. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. A rapid bedside blood glucose test was 89 mg/dL. The infant’s physical examination was unremarkable. She appeared active but hungry, had a strong cry, and had a developmentally appropriate gross neurological examination.

How does ethanol exposure in children typically occur?

Recent reports from the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System demonstrate that ethanol exposures comprise 1% to 3% of total exposures in children aged ≤5 years.

The most common sources are ethanol-containing beverages, mouthwash, and cologne/perfume.1 Ethanol can also be found as a solvent for certain pediatric liquid medications (eg, ranitidine) or in flavor extracts (eg, vanilla extract, orange extract). Any clear alcohol (eg, vodka, gin, rum) stored in an accessible site, such as a refrigerator, may be mistaken for water. In many reports, a caregiver unintentionally used the alcohol to reconstitute formula; however, intentional provision of alcohol to toddlers, usually as a sedative, is a recurring concern.2

What are the clinical concerns in children with ethanol intoxication?

Under usual conditions, a normal serum glucose concentration is maintained from ingested carbohydrates and via glycogenolysis of hepatic glycogen stores. Such glycogen reserves can sustain normal blood glucose concentrations for several hours in adults but for a shorter period in children. Once glycogen is depleted, as is common after an overnight fast, glucose can be generated through gluconeogenesis.

However, in the presence of ethanol (Figure), the excessive reducing potential (ie, NADH) that results from ethanol metabolism shunts pyruvate away from the gluconeogenic pathway (toward lactate), inhibiting glucose production. Unlike adults, children and infants, who have relatively low glycogen reserves, are at significant risk for hypoglycemia following ethanol exposure. This represents the largest contributor to morbidity and mortality of children with ethanol intoxication.3 Patients with hypoglycemia can have a highly variable clinical presentation including agitation, seizures, focality, or coma.4

Case Continuation

Intravenous (IV) access was obtained, and the patient was placed on a dextrose-containing fluid at 1.5 times the maintenance flow rate. Pertinent laboratory studies revealed a serum glucose level of 90 mg/dL, normal electrolyte panel, and an initial blood alcohol concentration of 337 mg/dL (approximately 30 minutes postingestion).

How do children with ethanol intoxication present?

While there is some variation in clinical effects among nontolerant adults, acute ethanol intoxication with a serum concentration >250 mg/dL is frequently associated with stupor, respiratory depression, and hypotension. A concentration >400 mg/dL may be associated with coma or apnea. Although similar clinical effects are expected in adolescents and children, infants often have counterintuitive clinical findings.

To date, eight cases of significant infant ethanol exposure exist in the literature (age range, 29 days to 9 months; ethanol concentration, 183-524 mg/dL). Respiratory depression was absent in all cases.5-9 In all but two cases, the neurological examination revealed only subtle decreases in interaction or tone. The remaining two children were described as obtunded and flaccid (ethanol levels, 405 mg/dL and 524 mg/dL, respectively) and were intubated for airway protection despite normal respiratory rates.7,10

The incongruence between the clinical findings (both the neurological examination and respiratory effects) and the ethanol concentration is difficult to explain. It may be due to age-related neurological immaturity or a limited ability to perform the required detailed neurological examinations in children. In particular, the relatively preserved level of consciousness, despite an otherwise coma-inducing ethanol concentration, is unique to infants. Accordingly, there should be a low threshold to check ethanol concentrations in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events, altered mental status, decreased tone, or unexplained hypoglycemia or hypothermia.

What is the estimated time to sobriety in infants?

Ethanol is eliminated via a hepatic enzymatic oxidation pathway that becomes saturated at low serum levels. In nontolerant adults, this results in a zero-order kinetic elimination pattern with an ethanol elimination rate of approximately 20 mg/dL per hour. Anecdotally, it had been thought that children clear ethanol at roughly double this rate via unclear mechanisms. However, a review of published kinetic data suggests the actual rate of clearance may not differ substantially from adults (range, 19-34 mg/dL per hour).5-7,10,11

Case Conclusion

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care pediatric hospital for continued management, where the markedly elevated serum ethanol concentration was confirmed. She was maintained on a dextrose-containing IV fluid and observed overnight without development of any complications. Serial serum ethanol concentrations were performed and complete clearance was achieved approximately 20 hours postingestion, suggesting a metabolic rate of 16 mg/dL per hour. The infant was discharged home with supervision by child protective services.

Dr Boroughf is a toxicology fellow, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Henretig is an attending toxicologist, department of emergency medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51(10):949-1229.

- Wood JN, Pecker LH, Russo ME, Henretig F, Christian CW. Evaluation and referral for child maltreatment in pediatric poisoning victims. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(4):362-369.

- Lamminpää A. Alcohol intoxication in childhood and adolescence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(1):5-12.

- Malouf R, Brust JC. Hypoglycemia: causes, neurological manifestations, and outcome. Ann Neurol.1985;17(5):421-430.

- Chikava K, Lower DR, Frangiskakis SH, Sepulveda JL, Virji MA, Rao KN. Acute ethanol intoxication in a 7-month old-infant. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7(4):400-402.

- Ford JB, Wayment MT, Albertson TE, Owen KP, Radke JB, Sutter ME. Elimination kinetics of ethanol in a 5-week-old infant and a literature review of infant ethanol pharmacokinetics. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:250716. doi:10.1155/2013/250716

- McCormick T, Levine M, Knox O, Claudius I. Ethanol ingestion in two infants under 2 months old: a previously unreported cause of ALTE. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2);e604-e607.

- Fong HF, Muller AA. An unexpected clinical course in a 29-day-old infant with ethanol exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(2):111-113.

- Iyer SS, Haupt A, Henretig FM. Pick your poison: straight from the spring? Ped Emerg Care. 2009;25(3):194-196.

- Edmunds SM, Ajizian SJ, Liguori A. Acute obtundation in a 9-month-old patient: ethanol ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(10):739-741.

- Simon HK, Cox JM, Sucov A, Linakis JG. Serum ethanol clearance in intoxicated children and adolescents presenting to the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(6):520-524.

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51(10):949-1229.

- Wood JN, Pecker LH, Russo ME, Henretig F, Christian CW. Evaluation and referral for child maltreatment in pediatric poisoning victims. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(4):362-369.

- Lamminpää A. Alcohol intoxication in childhood and adolescence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(1):5-12.

- Malouf R, Brust JC. Hypoglycemia: causes, neurological manifestations, and outcome. Ann Neurol.1985;17(5):421-430.

- Chikava K, Lower DR, Frangiskakis SH, Sepulveda JL, Virji MA, Rao KN. Acute ethanol intoxication in a 7-month old-infant. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7(4):400-402.

- Ford JB, Wayment MT, Albertson TE, Owen KP, Radke JB, Sutter ME. Elimination kinetics of ethanol in a 5-week-old infant and a literature review of infant ethanol pharmacokinetics. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:250716. doi:10.1155/2013/250716

- McCormick T, Levine M, Knox O, Claudius I. Ethanol ingestion in two infants under 2 months old: a previously unreported cause of ALTE. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2);e604-e607.

- Fong HF, Muller AA. An unexpected clinical course in a 29-day-old infant with ethanol exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(2):111-113.

- Iyer SS, Haupt A, Henretig FM. Pick your poison: straight from the spring? Ped Emerg Care. 2009;25(3):194-196.

- Edmunds SM, Ajizian SJ, Liguori A. Acute obtundation in a 9-month-old patient: ethanol ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(10):739-741.

- Simon HK, Cox JM, Sucov A, Linakis JG. Serum ethanol clearance in intoxicated children and adolescents presenting to the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(6):520-524.