User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m going to talk about something important to a lot of us, based on a new study that has just come out that promises to tell us the right way to exercise. This is a major issue as we think about the best ways to stay healthy.

There are basically two main types of exercise that exercise physiologists think about. There are aerobic exercises: the cardiovascular things like running on a treadmill or outside. Then there are muscle-strengthening exercises: lifting weights, calisthenics, and so on. And of course, plenty of exercises do both at the same time.

It seems that the era of aerobic exercise as the main way to improve health was the 1980s and early 1990s. Then we started to increasingly recognize that muscle-strengthening exercise was really important too. We’ve got a ton of data on the benefits of cardiovascular and aerobic exercise (a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality, and even improved cognitive function) across a variety of study designs, including cohort studies, but also some randomized controlled trials where people were randomized to aerobic activity.

We’re starting to get more data on the benefits of muscle-strengthening exercises, although it hasn’t been in the zeitgeist as much. Obviously, this increases strength and may reduce visceral fat, increase anaerobic capacity and muscle mass, and therefore [increase the] basal metabolic rate. What is really interesting about muscle strengthening is that muscle just takes up more energy at rest, so building bigger muscles increases your basal energy expenditure and increases insulin sensitivity because muscle is a good insulin sensitizer.

So, do you do both? Do you do one? Do you do the other? What’s the right answer here?

it depends on who you ask. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation, which changes from time to time, is that you should do at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity. Anything that gets your heart beating faster counts here. So that’s 30 minutes, 5 days a week. They also say you can do 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity – something that really gets your heart rate up and you are breaking a sweat. Now they also recommend at least 2 days a week of a muscle-strengthening activity that makes your muscles work harder than usual, whether that’s push-ups or lifting weights or something like that.

The World Health Organization is similar. They don’t target 150 minutes a week. They actually say at least 150 and up to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity. They are setting the floor, whereas the CDC sets its target and then they go a bit higher. They also recommend 2 days of muscle strengthening per week for optimal health.

But what do the data show? Why am I talking about this? It’s because of this new study in JAMA Internal Medicine by Ruben Lopez Bueno and colleagues. I’m going to focus on all-cause mortality for brevity, but the results are broadly similar.

The data source is the U.S. National Health Interview Survey. A total of 500,705 people took part in the survey and answered a slew of questions (including self-reports on their exercise amounts), with a median follow-up of about 10 years looking for things like cardiovascular deaths, cancer deaths, and so on.

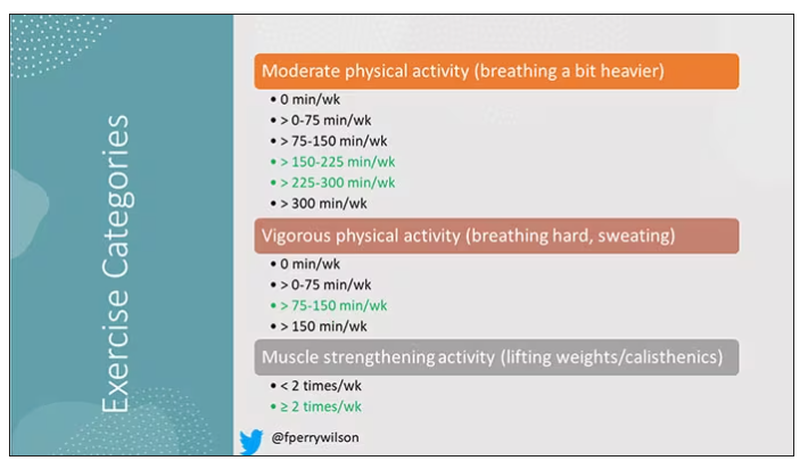

The survey classified people into different exercise categories – how much time they spent doing moderate physical activity (MPA), vigorous physical activity (VPA), or muscle-strengthening activity (MSA).

There are six categories based on duration of MPA (the WHO targets are highlighted in green), four categories based on length of time of VPA, and two categories of MSA (≥ or < two times per week). This gives a total of 48 possible combinations of exercise you could do in a typical week.

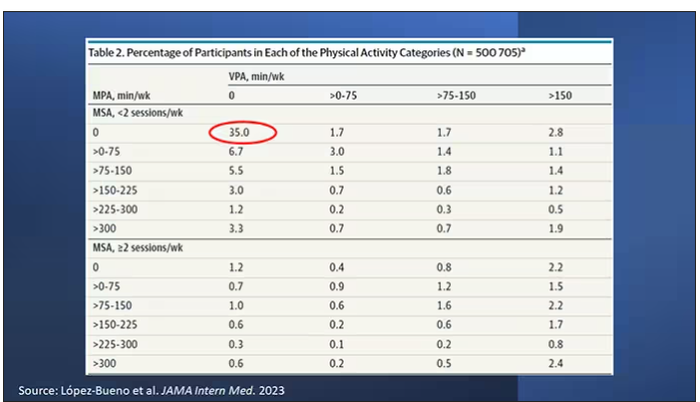

Here are the percentages of people who fell into each of these 48 potential categories. The largest is the 35% of people who fell into the “nothing” category (no MPA, no VPA, and less than two sessions per week of MSA). These “nothing” people are going to be a reference category moving forward.

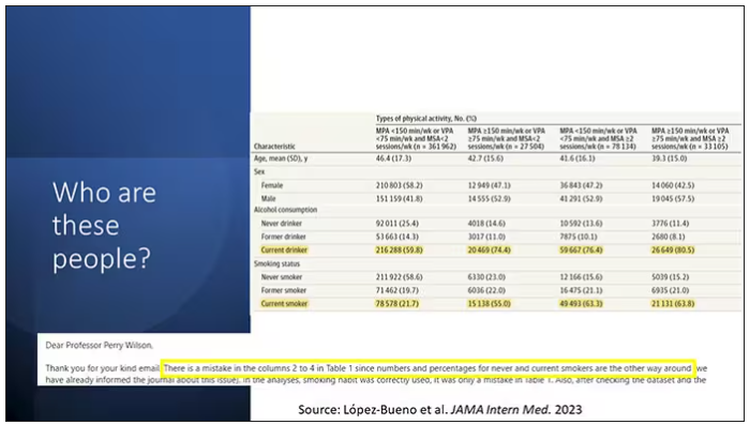

So who are these people? On the far left are the 361,000 people (the vast majority) who don’t hit that 150 minutes a week of MPA or 75 minutes a week of VPA, and they don’t do 2 days a week of MSA. The other three categories are increasing amounts of exercise. Younger people seem to be doing more exercise at the higher ends, and men are more likely to be doing exercise at the higher end. There are also some interesting findings from the alcohol drinking survey. The people who do more exercise are more likely to be current drinkers. This is interesting. I confirmed these data with the investigator. This might suggest one of the reasons why some studies have shown that drinkers have better outcomes in terms of either cardiovascular or cognitive outcomes over time. There’s a lot of conflicting data there, but in part, it might be that healthier people might drink more alcohol. It could be a socioeconomic phenomenon as well.

Now, what blew my mind were these smoker numbers, but don’t get too excited about it. What it looks like from the table in JAMA Internal Medicine is that 20% of the people who don’t do much exercise smoke, and then something like 60% of the people who do more exercise smoke. That can’t be right. So I checked with the lead study author. There is a mistake in these columns for smoking. They were supposed to flip the “never smoker” and “current smoker” numbers. You can actually see that just 15.2% of those who exercise a lot are current smokers, not 63.8%. This has been fixed online, but just in case you saw this and you were as confused as I was that these incredibly healthy smokers are out there exercising all the time, it was just a typo.

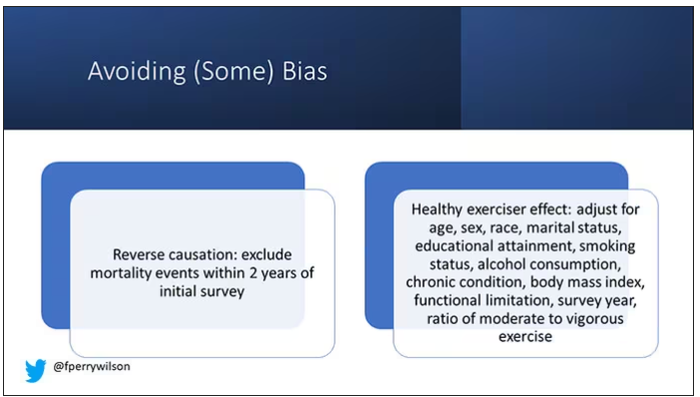

There is bias here. One of the big ones is called reverse causation bias. This is what might happen if, let’s say you’re already sick, you have cancer, you have some serious cardiovascular disease, or heart failure. You can’t exercise that much. You physically can’t do it. And then if you die, we wouldn’t find that exercise is beneficial. We would see that sicker people aren’t as able to exercise. The investigators got around this a bit by excluding mortality events within 2 years of the initial survey. Anyone who died within 2 years after saying how often they exercised was not included in this analysis.

This is known as the healthy exerciser or healthy user effect. Sometimes this means that people who exercise a lot probably do other healthy things; they might eat better or get out in the sun more. Researchers try to get around this through multivariable adjustment. They adjust for age, sex, race, marital status, etc. No adjustment is perfect. There’s always residual confounding. But this is probably the best you can do with the dataset like the one they had access to.

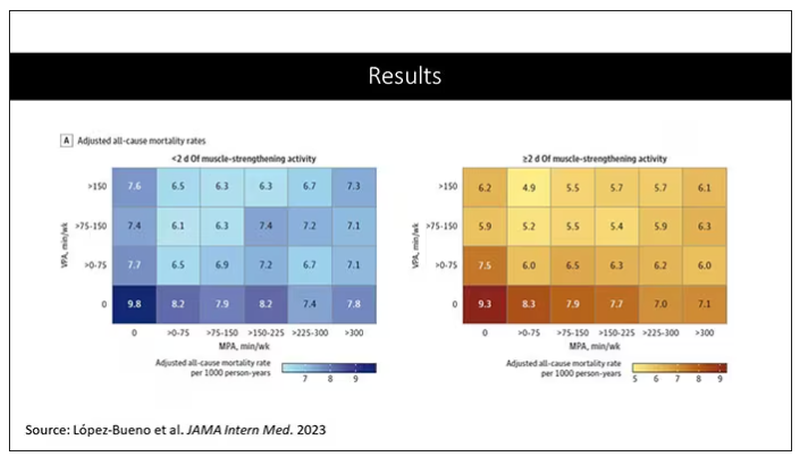

Let’s go to the results, which are nicely heat-mapped in the paper. They’re divided into people who have less or more than 2 days of MSA. Our reference groups that we want to pay attention to are the people who don’t do anything. The highest mortality of 9.8 individuals per 1,000 person-years is seen in the group that reported no moderate physical activity, no VPA, and less than 2 days a week of MSA.

As you move up and to the right (more VPA and MPA), you see lower numbers. The lowest number was 4.9 among people who reported more than 150 minutes per week of VPA and 2 days of MSA.

Looking at these data, the benefit, or the bang for your buck is higher for VPA than for MPA. Getting 2 days of MSA does have a tendency to reduce overall mortality. This is not necessarily causal, but it is rather potent and consistent across all the different groups.

So, what are we supposed to do here? I think the most clear finding from the study is that anything is better than nothing. This study suggests that if you are going to get activity, push on the vigorous activity if you’re physically able to do it. And of course, layering in the MSA as well seems to be associated with benefit.

Like everything in life, there’s no one simple solution. It’s a mix. But telling ourselves and our patients to get out there if you can and break a sweat as often as you can during the week, and take a couple of days to get those muscles a little bigger, may increase insulin sensitivity and basal metabolic rate – is it guaranteed to extend life? No. This is an observational study. We can’t say; we don’t have causal data here, but it’s unlikely to cause much harm. I’m particularly happy that people are doing a much better job now of really dissecting out the kinds of physical activity that are beneficial. It turns out that all of it is, and probably a mixture is best.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and interim director, program of applied translational research, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m going to talk about something important to a lot of us, based on a new study that has just come out that promises to tell us the right way to exercise. This is a major issue as we think about the best ways to stay healthy.

There are basically two main types of exercise that exercise physiologists think about. There are aerobic exercises: the cardiovascular things like running on a treadmill or outside. Then there are muscle-strengthening exercises: lifting weights, calisthenics, and so on. And of course, plenty of exercises do both at the same time.

It seems that the era of aerobic exercise as the main way to improve health was the 1980s and early 1990s. Then we started to increasingly recognize that muscle-strengthening exercise was really important too. We’ve got a ton of data on the benefits of cardiovascular and aerobic exercise (a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality, and even improved cognitive function) across a variety of study designs, including cohort studies, but also some randomized controlled trials where people were randomized to aerobic activity.

We’re starting to get more data on the benefits of muscle-strengthening exercises, although it hasn’t been in the zeitgeist as much. Obviously, this increases strength and may reduce visceral fat, increase anaerobic capacity and muscle mass, and therefore [increase the] basal metabolic rate. What is really interesting about muscle strengthening is that muscle just takes up more energy at rest, so building bigger muscles increases your basal energy expenditure and increases insulin sensitivity because muscle is a good insulin sensitizer.

So, do you do both? Do you do one? Do you do the other? What’s the right answer here?

it depends on who you ask. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation, which changes from time to time, is that you should do at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity. Anything that gets your heart beating faster counts here. So that’s 30 minutes, 5 days a week. They also say you can do 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity – something that really gets your heart rate up and you are breaking a sweat. Now they also recommend at least 2 days a week of a muscle-strengthening activity that makes your muscles work harder than usual, whether that’s push-ups or lifting weights or something like that.

The World Health Organization is similar. They don’t target 150 minutes a week. They actually say at least 150 and up to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity. They are setting the floor, whereas the CDC sets its target and then they go a bit higher. They also recommend 2 days of muscle strengthening per week for optimal health.

But what do the data show? Why am I talking about this? It’s because of this new study in JAMA Internal Medicine by Ruben Lopez Bueno and colleagues. I’m going to focus on all-cause mortality for brevity, but the results are broadly similar.

The data source is the U.S. National Health Interview Survey. A total of 500,705 people took part in the survey and answered a slew of questions (including self-reports on their exercise amounts), with a median follow-up of about 10 years looking for things like cardiovascular deaths, cancer deaths, and so on.

The survey classified people into different exercise categories – how much time they spent doing moderate physical activity (MPA), vigorous physical activity (VPA), or muscle-strengthening activity (MSA).

There are six categories based on duration of MPA (the WHO targets are highlighted in green), four categories based on length of time of VPA, and two categories of MSA (≥ or < two times per week). This gives a total of 48 possible combinations of exercise you could do in a typical week.

Here are the percentages of people who fell into each of these 48 potential categories. The largest is the 35% of people who fell into the “nothing” category (no MPA, no VPA, and less than two sessions per week of MSA). These “nothing” people are going to be a reference category moving forward.

So who are these people? On the far left are the 361,000 people (the vast majority) who don’t hit that 150 minutes a week of MPA or 75 minutes a week of VPA, and they don’t do 2 days a week of MSA. The other three categories are increasing amounts of exercise. Younger people seem to be doing more exercise at the higher ends, and men are more likely to be doing exercise at the higher end. There are also some interesting findings from the alcohol drinking survey. The people who do more exercise are more likely to be current drinkers. This is interesting. I confirmed these data with the investigator. This might suggest one of the reasons why some studies have shown that drinkers have better outcomes in terms of either cardiovascular or cognitive outcomes over time. There’s a lot of conflicting data there, but in part, it might be that healthier people might drink more alcohol. It could be a socioeconomic phenomenon as well.

Now, what blew my mind were these smoker numbers, but don’t get too excited about it. What it looks like from the table in JAMA Internal Medicine is that 20% of the people who don’t do much exercise smoke, and then something like 60% of the people who do more exercise smoke. That can’t be right. So I checked with the lead study author. There is a mistake in these columns for smoking. They were supposed to flip the “never smoker” and “current smoker” numbers. You can actually see that just 15.2% of those who exercise a lot are current smokers, not 63.8%. This has been fixed online, but just in case you saw this and you were as confused as I was that these incredibly healthy smokers are out there exercising all the time, it was just a typo.

There is bias here. One of the big ones is called reverse causation bias. This is what might happen if, let’s say you’re already sick, you have cancer, you have some serious cardiovascular disease, or heart failure. You can’t exercise that much. You physically can’t do it. And then if you die, we wouldn’t find that exercise is beneficial. We would see that sicker people aren’t as able to exercise. The investigators got around this a bit by excluding mortality events within 2 years of the initial survey. Anyone who died within 2 years after saying how often they exercised was not included in this analysis.

This is known as the healthy exerciser or healthy user effect. Sometimes this means that people who exercise a lot probably do other healthy things; they might eat better or get out in the sun more. Researchers try to get around this through multivariable adjustment. They adjust for age, sex, race, marital status, etc. No adjustment is perfect. There’s always residual confounding. But this is probably the best you can do with the dataset like the one they had access to.

Let’s go to the results, which are nicely heat-mapped in the paper. They’re divided into people who have less or more than 2 days of MSA. Our reference groups that we want to pay attention to are the people who don’t do anything. The highest mortality of 9.8 individuals per 1,000 person-years is seen in the group that reported no moderate physical activity, no VPA, and less than 2 days a week of MSA.

As you move up and to the right (more VPA and MPA), you see lower numbers. The lowest number was 4.9 among people who reported more than 150 minutes per week of VPA and 2 days of MSA.

Looking at these data, the benefit, or the bang for your buck is higher for VPA than for MPA. Getting 2 days of MSA does have a tendency to reduce overall mortality. This is not necessarily causal, but it is rather potent and consistent across all the different groups.

So, what are we supposed to do here? I think the most clear finding from the study is that anything is better than nothing. This study suggests that if you are going to get activity, push on the vigorous activity if you’re physically able to do it. And of course, layering in the MSA as well seems to be associated with benefit.

Like everything in life, there’s no one simple solution. It’s a mix. But telling ourselves and our patients to get out there if you can and break a sweat as often as you can during the week, and take a couple of days to get those muscles a little bigger, may increase insulin sensitivity and basal metabolic rate – is it guaranteed to extend life? No. This is an observational study. We can’t say; we don’t have causal data here, but it’s unlikely to cause much harm. I’m particularly happy that people are doing a much better job now of really dissecting out the kinds of physical activity that are beneficial. It turns out that all of it is, and probably a mixture is best.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and interim director, program of applied translational research, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m going to talk about something important to a lot of us, based on a new study that has just come out that promises to tell us the right way to exercise. This is a major issue as we think about the best ways to stay healthy.

There are basically two main types of exercise that exercise physiologists think about. There are aerobic exercises: the cardiovascular things like running on a treadmill or outside. Then there are muscle-strengthening exercises: lifting weights, calisthenics, and so on. And of course, plenty of exercises do both at the same time.

It seems that the era of aerobic exercise as the main way to improve health was the 1980s and early 1990s. Then we started to increasingly recognize that muscle-strengthening exercise was really important too. We’ve got a ton of data on the benefits of cardiovascular and aerobic exercise (a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality, and even improved cognitive function) across a variety of study designs, including cohort studies, but also some randomized controlled trials where people were randomized to aerobic activity.

We’re starting to get more data on the benefits of muscle-strengthening exercises, although it hasn’t been in the zeitgeist as much. Obviously, this increases strength and may reduce visceral fat, increase anaerobic capacity and muscle mass, and therefore [increase the] basal metabolic rate. What is really interesting about muscle strengthening is that muscle just takes up more energy at rest, so building bigger muscles increases your basal energy expenditure and increases insulin sensitivity because muscle is a good insulin sensitizer.

So, do you do both? Do you do one? Do you do the other? What’s the right answer here?

it depends on who you ask. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation, which changes from time to time, is that you should do at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity. Anything that gets your heart beating faster counts here. So that’s 30 minutes, 5 days a week. They also say you can do 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity – something that really gets your heart rate up and you are breaking a sweat. Now they also recommend at least 2 days a week of a muscle-strengthening activity that makes your muscles work harder than usual, whether that’s push-ups or lifting weights or something like that.

The World Health Organization is similar. They don’t target 150 minutes a week. They actually say at least 150 and up to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity. They are setting the floor, whereas the CDC sets its target and then they go a bit higher. They also recommend 2 days of muscle strengthening per week for optimal health.

But what do the data show? Why am I talking about this? It’s because of this new study in JAMA Internal Medicine by Ruben Lopez Bueno and colleagues. I’m going to focus on all-cause mortality for brevity, but the results are broadly similar.

The data source is the U.S. National Health Interview Survey. A total of 500,705 people took part in the survey and answered a slew of questions (including self-reports on their exercise amounts), with a median follow-up of about 10 years looking for things like cardiovascular deaths, cancer deaths, and so on.

The survey classified people into different exercise categories – how much time they spent doing moderate physical activity (MPA), vigorous physical activity (VPA), or muscle-strengthening activity (MSA).

There are six categories based on duration of MPA (the WHO targets are highlighted in green), four categories based on length of time of VPA, and two categories of MSA (≥ or < two times per week). This gives a total of 48 possible combinations of exercise you could do in a typical week.

Here are the percentages of people who fell into each of these 48 potential categories. The largest is the 35% of people who fell into the “nothing” category (no MPA, no VPA, and less than two sessions per week of MSA). These “nothing” people are going to be a reference category moving forward.

So who are these people? On the far left are the 361,000 people (the vast majority) who don’t hit that 150 minutes a week of MPA or 75 minutes a week of VPA, and they don’t do 2 days a week of MSA. The other three categories are increasing amounts of exercise. Younger people seem to be doing more exercise at the higher ends, and men are more likely to be doing exercise at the higher end. There are also some interesting findings from the alcohol drinking survey. The people who do more exercise are more likely to be current drinkers. This is interesting. I confirmed these data with the investigator. This might suggest one of the reasons why some studies have shown that drinkers have better outcomes in terms of either cardiovascular or cognitive outcomes over time. There’s a lot of conflicting data there, but in part, it might be that healthier people might drink more alcohol. It could be a socioeconomic phenomenon as well.

Now, what blew my mind were these smoker numbers, but don’t get too excited about it. What it looks like from the table in JAMA Internal Medicine is that 20% of the people who don’t do much exercise smoke, and then something like 60% of the people who do more exercise smoke. That can’t be right. So I checked with the lead study author. There is a mistake in these columns for smoking. They were supposed to flip the “never smoker” and “current smoker” numbers. You can actually see that just 15.2% of those who exercise a lot are current smokers, not 63.8%. This has been fixed online, but just in case you saw this and you were as confused as I was that these incredibly healthy smokers are out there exercising all the time, it was just a typo.

There is bias here. One of the big ones is called reverse causation bias. This is what might happen if, let’s say you’re already sick, you have cancer, you have some serious cardiovascular disease, or heart failure. You can’t exercise that much. You physically can’t do it. And then if you die, we wouldn’t find that exercise is beneficial. We would see that sicker people aren’t as able to exercise. The investigators got around this a bit by excluding mortality events within 2 years of the initial survey. Anyone who died within 2 years after saying how often they exercised was not included in this analysis.

This is known as the healthy exerciser or healthy user effect. Sometimes this means that people who exercise a lot probably do other healthy things; they might eat better or get out in the sun more. Researchers try to get around this through multivariable adjustment. They adjust for age, sex, race, marital status, etc. No adjustment is perfect. There’s always residual confounding. But this is probably the best you can do with the dataset like the one they had access to.

Let’s go to the results, which are nicely heat-mapped in the paper. They’re divided into people who have less or more than 2 days of MSA. Our reference groups that we want to pay attention to are the people who don’t do anything. The highest mortality of 9.8 individuals per 1,000 person-years is seen in the group that reported no moderate physical activity, no VPA, and less than 2 days a week of MSA.

As you move up and to the right (more VPA and MPA), you see lower numbers. The lowest number was 4.9 among people who reported more than 150 minutes per week of VPA and 2 days of MSA.

Looking at these data, the benefit, or the bang for your buck is higher for VPA than for MPA. Getting 2 days of MSA does have a tendency to reduce overall mortality. This is not necessarily causal, but it is rather potent and consistent across all the different groups.

So, what are we supposed to do here? I think the most clear finding from the study is that anything is better than nothing. This study suggests that if you are going to get activity, push on the vigorous activity if you’re physically able to do it. And of course, layering in the MSA as well seems to be associated with benefit.

Like everything in life, there’s no one simple solution. It’s a mix. But telling ourselves and our patients to get out there if you can and break a sweat as often as you can during the week, and take a couple of days to get those muscles a little bigger, may increase insulin sensitivity and basal metabolic rate – is it guaranteed to extend life? No. This is an observational study. We can’t say; we don’t have causal data here, but it’s unlikely to cause much harm. I’m particularly happy that people are doing a much better job now of really dissecting out the kinds of physical activity that are beneficial. It turns out that all of it is, and probably a mixture is best.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and interim director, program of applied translational research, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.